Introduction

The intersection of land and sea both defines Australia’s borders and characterises the Australian military’s primary operating environment. With 90 per cent of the global population living within 1,000 km of a coastline (including 40 per cent living within 100 km), 90 per cent of international trade traveling between ports, and 95 per cent of global communication transmitted through submarine cables, littoral environments hold significant strategic importance.[1] Nevertheless, the conduct of littoral operations has not always been at the forefront of Australian military thinking. Despite Australia’s extensive littoral experience during the Second World War, Defence White Papers from the 1970s to the 1990s focused narrowly on the northern approaches to continental Australia (known as the ‘air-sea gap’) while largely ignoring the land component of the littoral environment.[2] These ‘Defence of Australia’ policies emphasised the roles of the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) and Royal Australian Airforce (RAAF) while relegating the Army to rear security across northern Australia.[3] The shortcomings of this approach became clear when violence engulfed one of Australia’s northern neighbours, East Timor, in 1999.

The Australian-led intervention into the country now known as Timor-Leste highlighted the need for expeditionary land forces capable of operating in Australia’s near region. Subsequent White Papers responded to this realisation by seeking to close the capability gaps that had existed under the ‘Defence of Australia’ policies, including by establishing the Australian Amphibious Force.[4] Although amphibious forces were a step forward, recent strategic updates have provided the impetus for the Australian Defence Force (ADF) to reconsider littoral operations in broader terms, including through the development of ‘Army littoral manoeuvre’ capabilities.[5] As General David Berger, the former Commandant of the United States Marine Corps (USMC) has emphasised through the Force Design 2030 initiative, littoral operations required broader concepts and capabilities than amphibious operations alone.[6] Like any opportunity for change, Australia’s renewed interest in littoral operations brings with it uncertainty. What exactly are littoral operations? How do they differ from amphibious operations, if at all? How do littoral operations relate to maritime strategy? Answering these questions will set the ADF on the right path to overcome the challenges and exploit the opportunities that littoral environments provide.

While the ADF is increasingly using the term littoral operations to describe future capabilities and force structures, it is yet to establish a common understanding of what littoral operations are. Milan Vego has argued that ‘perhaps the most important prerequisite of success in littoral warfare is a solid theory developed ahead of time; otherwise, it is not possible to organise and train forces properly’.[7] The crucial first step towards developing such a theory is to define littoral operations clearly and distinctively. Surprisingly, such a definition is not readily available, with littoral operations caught between the narrower concept of amphibious operations and the broader concept of maritime strategy. The second step to establishing an effective theory for littoral operations is to identify the most important considerations that should guide force design, planning, and operational execution. Much like the principles of war[8] or tenets of manoeuvre,[9] establishing tenets for littoral operations offers guideposts to support decision-making. By defining littoral operations in terms that are broader than, but also inclusive of, amphibious operations, and by seeking to achieve cross-domain mobility, cross-domain effects, unified command and control (C2), endurance and interoperability during these operations, Australia can exploit the opportunities that littoral environments provide.

Framing and Defining Littoral Operations

The concept of littoral operations offers the greatest value if it is broader than traditional definitions of amphibious operations (incorporating the latter as a subset) while remaining within the wider context of maritime strategy. If the ADF defines littoral operations so broadly that they mirror maritime strategy, then the former term is redundant. Likewise, if amphibious and littoral operations are equivalent terms, then using the latter terminology provides no value. Further, expanding existing amphibious definitions to incorporate the full spectrum of possible littoral operations risks diluting these important concepts. Fortunately, while the capabilities and force structures the ADF is developing are new, Australian operations in littoral regions are not. From Gallipoli to the South West Pacific Area, to Timor-Leste, Australia has a broad military history from which to draw the necessary lessons for the future. Establishing a definition for littoral operations that provides distinction from amphibious operations while nesting within the concept of maritime strategy would enable the ADF to frame littoral operations in a manner that exploits the full range of unique military opportunities. Figure 1 represents the author’s proposed relationship between maritime strategy, littoral operations, and amphibious operations.

Figure 1: Proposed relationship between maritime strategy, littoral operations, and amphibious operations

While the concept of maritime strategy incorporates the littoral environment, it necessarily does not delve into the detail required to conduct successful littoral operations. On the other hand, amphibious operations are generally described in ship-to-shore terms that exclude a range of potential littoral actions. Current Australian doctrine recognises five types of amphibious operations (demonstration, raid, assault, withdrawal, and support to other operations), all of which feature a ship-to-shore focus.[10] The employment of a Navy-Marine Expeditionary Ship Interdiction System (NMESIS) inserted by C-17 aircraft to deny a key shipping lane offers an example of a potential littoral operation that would not include a ship-to-shore component. Coastal defence operations and the expeditionary advanced base operations (EABO)[11] concept developed by the USMC offer further examples that are not necessarily amphibious but are certainly littoral.[12] Nevertheless, amphibious operations remain complex and should therefore remain a distinct and important subset within the broader concept of littoral operations. If littoral operations are narrower than maritime strategy but broader than amphibious operations, how then should they be defined?

Examining the key theoretical foundations for maritime strategy offers a useful start point for developing a meaningful definition for littoral operations. Given that littoral operations reside at the boundary between discrete land and naval operations, they necessarily form a subset of maritime strategy. Alfred Thayer Mahan, a key influence on US concepts of maritime strategy, argued that ‘the use and control of the sea is and has been a great factor in the history of the world’.[13] Writing in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Mahan sought to redress a perceived disinterest in sea power as a component of national power. Mahan contended that blockades and decisive naval battles were the key actions within successful strategies, arguing that ‘nations, like men, however strong, decay when cut off from the external activities and resources which at once draw out and support their internal powers’.[14] By elevating the profile of naval operations, Mahan’s work contributed to concepts of maritime strategy that value naval forces alongside those on land. Still relevant today, Mahan’s work suggests that the ADF should continue to give the maritime domain due weight alongside the land domain when conceptualising littoral operations.

Whereas Mahan conceptualised land and naval operations as discrete options competing for primacy, Julian Corbett’s Some Principles of Maritime Strategy recognised their critical interdependence. Corbett argued that habit and a lack of scientific thought had resulted in land and naval strategy being considered separately, whereas ‘embracing them both is a larger strategy which regards the fleet and army as one weapon’.[15] By defining maritime strategy as ‘the principles which govern a war in which the sea is a substantial factor’, including determining ‘what part the fleet must play in relation to the action of the land forces’,[16] Corbett was able to integrate traditionally disparate land and naval concepts. He was particularly interested in integrating land and naval forces to conduct limited war, employing navies to isolate discrete areas while seizing limited objectives on land. Corbett recognised that strategic priorities may shift between naval and land forces, writing:

It may be that the command of the sea is of so urgent an importance that the army will have to devote itself to assisting the fleet … on the other hand, it may be that the immediate duty of the fleet will be to forward military action ashore.[17]

While littoral operations are not confined to the conduct of limited war, Corbett’s conceptualisation of strategies, which integrated both land and naval forces, suggests that an ADF definition for littoral operations must likewise value both land and maritime domains equally.

Although the theories of Mahan and Corbett shaped maritime strategy in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, concepts for amphibious operations pre-date both by several centuries. Amphibious operations have been conducted since at least as early as 490 BC,[18] albeit that formalised and cohesive amphibious doctrine did not emerge until the 18th century when, in 1759, Thomas More Molyneux published Conjunct Expeditions.[19] Reflecting on the failure of British forces to capture the French port at Rochefort during the Seven Years War, Molyneux identified that:

… the Littoral War where our Fleet and Army act together, hath ever been in so low esteem, that no one hath applied himself sufficiently to that fort of Study, to explore its real Virtues.[20]

Molyneux offered a compelling assessment of the challenges and opportunities that littoral operations present:

[A] Military, Naval, Littoral War, when wi[s]ely prepared and discreetly conducted, is a terrible Sort of War. Happy for that People who are Sovereigns enough of the Sea to put it in Execution! For it comes like Thunder and Lightning to some unprepared Part of the World.[21]

Molyneux’s concepts are readily recognisable in modern amphibious operations; his work identifies the landing, operations ashore, and re-embarkation as key distinct phases while emphasising the importance of ‘mass, surprise, and momentum’.[22] Not only did Molyneux’s writing shape the subsequent conduct of the Seven Years War; his contributions ‘can rightly claim paternity of amphibious doctrine’.[23] Like the theories presented by Corbett, Molyneux’s work suggests that littoral operations should be defined in terms that best integrate both land and maritime forces.

While Conjunct Expeditions formed the first amphibious doctrine, the further development of littoral operations has continued over the subsequent centuries. Seeking to learn from the Allied experiences at Gallipoli, the USMC invested heavily in education, doctrinal development, and practical experimentation between 1918 and 1939 to refine concepts for amphibious landings and other littoral operations. The USMC formalised its amphibious doctrine in the ‘Tentative Manual for Landing Operations’ issued in 1934. The operational complexity reflected in the ‘Tentative Manual for Landing Operations’ (and subsequently demonstrated during the Second World War) highlights the need to retain amphibious operations as a distinct concept rather than diluting it with the wider opportunities presented by the littoral environment. Concurrent to the development of amphibious capabilities, the USMC developed doctrine for other forms of littoral operations, including the ‘Tentative Manual for Defense of Advanced Bases’, which in 1936 detailed coastal defence and the establishment of expeditionary advanced bases. While USMC doctrine during the interwar period did not use the term littoral operations as an overarching concept, it nevertheless recognised that military operations in littoral regions are not limited to ship-to-shore actions. Accordingly, the ADF should define littoral operations in terms that incorporate amphibious operations as a distinct subset while also covering operations that do not fit traditional ship-to-shore constructs.

Figure 2: Australian Army soldiers post security for an amphibious raid during a multinational littoral operations exercise as part of Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) 2022. CPL Arianna Lindheimer, Department of Defence, 220801-M-AL123-1351.[24]

It was not until 2017 that littoral operations gained momentum as a distinct concept within the US military when it began deliberately using the term to shape thinking beyond ship-to-shore actions while developing contemporary operational concepts. Specifically, in ‘Littoral Operations in a Contested Environment’ (LOCE) the US Chief of Naval Operations and the Commandant of the Marine Corps explicitly employed the term littoral ‘to frame the content in a manner that is much broader than just amphibious operations’.[25] LOCE sought to develop ‘additional, versatile force options; a wider application of existing doctrine; and the more flexible employment of current, emerging, and some potential capabilities’[26] for use in contested littoral environments. Recognising the increasing challenges that littoral operations present, LOCE argued:

[T]he range of modern sensors and weapons extends hundreds of miles both seaward and landward, blurring the distinction between operations at sea and on land and necessitating an operational approach that treats the littorals as a singular, integrated battlespace.[27]

The approach taken by the US reinforces the need for the ADF to define littoral operations in terms that are broader than but still include amphibious operations.

Like the US, the UK has recognised that the littoral environment offers broader scope for military actions than just those considered under the banner of amphibious operations. The UK’s 2022 Maritime Operating Concept highlights the importance of littoral operations by positioning ‘littoral strike’ as one of the four key organisational outputs.[28] Building on the Future Commando Force modernisation program,[29] the Maritime Operating Concept lists the provision of ‘an amphibious advance force able to ensure rapid entry to the fight’ as just one necessary littoral capability amongst many.[30] ‘Joint Doctrine Publication 0-10 UK Maritime Power’, released in 2017, proposed that the definition of a littoral region should be expanded to include ‘those areas of the sea susceptible to engagement from the land, from both land and air forces’[31] (although that change has not yet been implemented in the ‘UK Terminology Supplement’).[32] The UK’s decision to highlight the importance of littoral operations as a distinct military concept further reinforces the need for the ADF to establish a clear and concise definition that encapsulates the full scope of littoral operations.

While both contemporary concepts and historical operations demonstrate the breadth of opportunities that littoral operations provide, current formal definitions have failed to adequately articulate the concept. The term littoral has a scientific rather than military foundation: ‘at its most basic, littoral relates to coasts and coastal regions, deriving from the Latin word for “shore”’.[33] Nevertheless, military littoral concepts have expanded beyond the shoreline:

[I]n both seaward and landward terms, the notion and size of the littoral area evolves, driven by the technology that increases the range of weapons and mobility platforms that can affect and operate within these littoral areas.[34]

As militaries increase their ability to project force across the land and maritime domain boundary, the size of the littoral environment grows. Adding to the lack of clarity, many definitions (including the current Australian definition of ‘littoral manoeuvre’,[35] the US definition of ‘littoral’,[36] and the UK definitions of ‘littoral manoeuvre’ and ‘littoral region’[37]) reflect only ship-to-shore concepts and therefore mirror amphibious operations. If littoral operations and amphibious operations are the same, having both terms only causes confusion. Clearly defining littoral operations in broader terms is therefore key to exploiting the opportunities that exist outside of ship-to-shore operations within a littoral environment.

Given the insights offered by Mahan, Corbett and Molyneux, as well as the US and UK militaries, how then should the ADF define littoral operations? The ADF Glossary[38] does not currently contain an authorised definition for littoral operations; however, the 2017 RAN publication ‘Australian Maritime Operations’ suggests that ‘littoral operations are those influenced by the interface between the land and the sea. These can encompass the entire spectrum of operations’.[39] This definition succeeds in framing a wider concept than just ship-to-shore operations; however, it is likely too broad to be genuinely useful. Army’s now obsolete ‘Manoeuvre Operations in the Littoral Environment’ (MOLE) doctrine published in 2004 described ‘littoral’ as ‘that area defined by the close proximity of the land, sea and air, where the operational effects of land, sea and aerospace power would overlap’.[40] By highlighting the cross-domain effects that characterise littoral operations, the MOLE definition offers a strong starting point. Building on the RAN and MOLE definitions, and recognising the lessons gleaned from historical theorists and allied militaries, the ADF should define littoral operations as:

Operations conducted in areas defined by the close proximity of the land and sea where the greatest military advantaged is achieved by treating land and water as a cohesive, interrelated battlespace.

By adopting this definition, the ADF can establish a common understanding of littoral operations that will support their successful conduct.

Establishing Tenets for Littoral Operations

A conceptual framework underpinned by the establishment of a clear definition of littoral operations can be further enhanced by establishing a list of tenets to guide planning, force structures, and the execution of operations. Such a list of tenets would guide ADF efforts to exploit opportunities and minimise challenges within the littoral environment. Existing doctrinal lists such as the principles of war[41] and tenets of manoeuvre[42] have demonstrated the utility of this approach. These existing lists were established on strong historical footing, yet they have been incrementally adjusted over time through further organisational experience. Accordingly, the ADF should establish tenets for littoral operations based on lessons from the past, while further developing this framework into the future. British statistician George EP Box’s often-quoted observation that ‘all models are wrong, but some are useful’[43] reinforces that a list of tenets cannot guarantee success but that they can nevertheless offer a useful model for conducting littoral operations. The measure of a list of tenets is their usefulness rather than their ability to provide certainty. A review of historical operations and recent US littoral concepts suggests that cross-domain mobility, cross-domain effects, unified C2, endurance, and interoperability offer a sound foundation for the ADF to employ as five tenets for littoral operations.

Tenet 1: Cross-Domain Mobility

The opportunity to employ cross-domain mobility, transitioning between the movement of forces on land and on water, offers unique advantages during littoral operations. Cross-domain mobility allows forces to bypass surfaces in one domain by exploiting gaps in another. Whereas land operations treat the water as an obstacle, and naval operations view land as a barrier, littoral operations are most effective when both are employed as manoeuvre space. The USMC Force Design 2030 initiative has identified mobility within littoral regions as ‘a competitive advantage and an operational imperative’, with experimentation highlighting a need for ‘operational and tactical mobility to provide joint force commanders a capability that operates with minimal dependence on theatre lift assets’.[44] Forces that can seamlessly transition between movement on land and movement on water (including for shore-to-shore manoeuvre) have a significant advantage during the conduct of littoral operations.

From a historical perspective, the Australian 9th Division’s advance to Lae, New Guinea, in 1943 highlights the impact that a lack of cross-domain mobility can have on littoral operations. Having redeployed to New Guinea following ‘an arduous desert campaign in the Middle East which included the eight-month defence of Tobruk against Rommel’s Afrika Korps’,[45] the 9th Division successfully executed the first large-scale Australian amphibious assault since Gallipoli. Following the amphibious assault, the 9th Division was to ‘advance through rugged country to the major Japanese stronghold of Lae where it would link with the 7th Division to capture the town and its crucial airbases, probably in the face of stiff opposition’.[46] Despite generating initial tempo against the defending Japanese, the 9th Division’s momentum was significantly impeded by an inability to move ‘troops in bounds along the coast and so avoid the slogging march along the coastal flats’[47] and by its inability to cross the swollen Busu River.[48] After a five-day delay the advance continued,[49] but not before allowing ‘the Japanese to adapt their plans to not only oppose the 9th Division’s advance, but also conduct an effective withdrawal to the north of Lae’.[50] Had the 9th Division been capable of cross-domain mobility, the watercourses around Lae would have offered an opportunity rather than an obstacle.

Tenet 2: Cross-Domain Effects

The close proximity of the land and sea, as well as the interrelations between land and maritime effects, make cross-domain effects an obvious tenet of littoral operations. Cross-domain effects refer to the ability of a force to deliver effects outside of the domain where that capability resides, including fires; intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR); and information warfare. The ability of an anti-shipping missile system to engage targets in the maritime domain from the land domain is an example of a cross-domain effect. Littoral operations are more potent when effects can be applied across domain boundaries to enable land, air, and maritime forces to threaten adversaries while shielding their own capabilities. The previous Commandant of the USMC, General Berger, highlighted the need for a force that can ‘provide critical links for highly lethal naval and joint fires kill chains’.[51] His predecessor General Robert Neller emphasised the need to ‘integrate Navy and Marine Corps lethal and non-lethal effects from afloat and ashore’.[52] Cross-domain effects enable forces conducting littoral operations to achieve both dispersed and disproportionate impacts.

The 1555 siege of Porto Ercole in Tuscany by Imperial Florentine land and maritime forces during the Habsburg-Valois War demonstrated the impact of cross-domain effects during littoral operations. Prior to the capture of the island of Porto Ercoletto, cannons emplaced within the French-Sienese fort prevented Imperial Florentine naval forces from entering or blockading the harbour to support the ongoing siege.[53] Much like modern ground-based anti-shipping missiles, the ability of these land-based fires to target the maritime domain achieved a disproportionate effect. The seizure of the fort through a special operation proved to be the ‘turning point in the siege’.[54] With the threat of land-based cannon fire from the fort removed, the Imperial Florentine fleet was able to block access to the harbor from the sea and offload cannons to support the subsequent operations on land. [55] With the necessary maritime conditions set, Imperial Florentine land forces were able to resume the offensive and force the surrender of the French-Sienese garrison.[56] The ability of the fort at Porto Ercoletto to apply cross-domain fires had been decisive; with the fort intact, neither naval nor land operations against Porto Ercole could succeed. Once these cross-domain effects were neutralised, the French-Sienese garrison quickly fell.

Tenet 3: Unified Command and Control

Given that militaries conduct littoral operations where multiple domains intersect, operational C2 must be genuinely unified across domains to exploit all of the available opportunities. Without this unified perspective, forces will likely regress to focusing on their traditional domain and will, therefore, miss critical opportunities. While examining the differences between littoral warfare and open ocean naval operations, Milan Vego has argued that C2 should ‘be centralized at the operational level’, while tactical C2 should be highly decentralised, should employ ‘mission command’, and should seek a ‘simple and streamlined littoral command structure, with the fewest possible intermediate levels’.[57] The US LOCE concept likewise recognises the need for unified C2, stating that ‘task organizations will fight with unity of command, employing networked, sea-based and land-based capabilities as well as common doctrine and operating principles’.[58] Seeking to achieve the necessary unity, the USMC ‘Tentative Manual for Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations’ (TMEABO) has recently introduced the term ‘Littoral Force Commander’ to refer to ‘the officer who commands all forces within a littoral operations area’.[59] While the need for unified C2 may appear obvious, history has demonstrated the need for militaries to actively ensure that it is genuinely achieved if they are to avoid failure.

From a historical perspective, a wide range of examples illustrate the importance of unified C2 during littoral operations. One of the most significant examples is the failed 1757 British raid on Rochefort during the Seven Years War, which resulted in the writing of the first amphibious doctrine. British forces surprised the French at Rochefort with the arrival of ‘thirty-one ships of war, forty-nine transports, and ten battalions of soldiers’.[60] Nevertheless the British land and naval commanders were unable to agree on a plan, resulting in the raiding party wasting the opportunity and withdrawing. The failure of this raid ‘can be attributed in part to the fact that the question of command responsibilities had not been settled before the operation’.[61] With no single commander able to exercise unified C2, the conflict between land and naval considerations could not be overcome. Thomas Molyneux’s subsequent publication of Conjunct Expeditions played a key role in ensuring that the British would not repeat this mistake: ‘much was learned from Rochefort, for confusion concerning command responsibilities is not evident in subsequent amphibious campaigns of the Seven Years War’.[62]

Tenet 4: Endurance

Forces conducting littoral operations are continuously exposed to adversary multi-domain effects, therefore their success or failure is predicated on their level of endurance. Achieving this endurance requires forces to optimise their survivability, maintain sustainment and maximise resilience. The proliferation of modern sensors and long-range strike capabilities has made this a significant challenge, requiring mass and dispersion to be deliberately balanced to assure survivability.[63] As General Berger has highlighted, ‘wargame after wargame suggests, fixed land bases and high-signature land forces will be vulnerable to long-range precision weapons. Large naval vessels will likewise initially face considerable risk’.[64] Sustaining dispersed littoral forces increases the exposure of logistical nodes and distribution networks to multi-domain threats, necessitating further deliberate balancing of competing risks. The challenge of sustaining littoral operations is so significant that the USMC has recognised that in a ‘distributed and contested environment, logistics is the pacing function for the Marine Corps’.[65] Endurance in many littoral environments is further challenged by tropical heat or glacial cold; while the rapidly increasing urbanisation of littoral areas ‘will mentally and physically deplete soldiers at an exponentially faster rate than combat in other environments’.[66] Absent the survivability, sustainability and resilience necessary to maintain endurance in a littoral environment, any capabilities a military force can otherwise offer become irrelevant.

The failure of Argentinian forces to execute a littoral defence and retain the Islas Malvinas (Falkland Islands) during Operación Azul highlights the importance of endurance during littoral operations. Despite achieving a successful coup de main on 1 April, by 11 June 1982 the last of the Argentinian defenders had surrendered.[67] Shortfalls in both sustainment and resilience undermined the endurance of the Argentinian defence:

The conscripts sent to defend the Falklands were poorly trained and led, did not adapt well to the harsh South Atlantic winter, lacked motivation and were not supported well logistically.[68]

The resilience of the Argentinian defence suffered most from a lack of long-term professional soldiers. The Argentinian military relied on intakes of short-term conscripts to generate combat power—there was ‘no such thing as a “regular” private soldier’.[69] The failure to overcome the British blockade further undermined the endurance of the defences, depriving defending forces of weapons, ammunition, and equipment[70] while forcing a reduction in ration allocations.[71] Unable to achieve the sustainability or resilience required to persist against an enemy that exploited all of the converging domains, Argentinian forces were unable to secure their initial gains.

Tenet 5: Interoperability

The inherent complexity generated by the convergence of domains during littoral operations makes joint and coalition interoperability not just a force multiplier but an essential tenet. Historians have described littoral operations as ‘inherently joint (multiservice) and often combined (multinational)’[72] and as requiring ‘nothing short of the acme of combined arms and joint warfare’.[73] Interoperability requires more than varied services and nations simply working alongside each other; abilities to effectively communicate, share intelligence, integrate fires, and share sustainment are all critical. Further, not only does interoperability support the ability of forces to achieve cross-domain effects and maintain endurance but also it ensures that forces are flexible enough to exploit the wide range of littoral environments. Interoperability can ensure that ‘the enemy is put at a great disadvantage against a multidimensional threat for which he might not have an effective counter’;[74] however, it also requires ‘sustained engagement with regional allies to maintain access and ensure support while operating in the regional littorals’.[75] While joint and coalition interoperability are essential for littoral operations, this integration does add further complexity to an already complex environment.[76] Despite these inherent challenges, the successful conduct of littoral operations requires forces capable of effectively supporting and being supported by joint and coalition partners.

Reinforcing the importance of interoperability, only good luck prevented Australia’s first amphibious operation of the Second World War, Operation DRAKE, from becoming a disaster. Commencing on 22 October 1942, Operation DRAKE sought to clear Japanese special naval landing forces from Goodenough Island to the east of the New Guinea mainland.[77] In addition to the landing force lacking any previous amphibious training, the last-minute planning of the operation prevented rehearsals between the land and naval components.[78] Unable to move closer to shore, naval vessels disembarked the landing force 150 metres or further from the beach, ‘leaving the infantry to wade through shin-deep water in the darkness and heavy rain’.[79] Once the landing was complete, the assigned naval forces immediately departed, leaving the force ashore with only the stores that they had already landed. While the absence of Japanese opposition during the landing mitigated the effects of these shortfalls, the lack of interoperability continued to disrupt the land force as the operation progressed.

Both joint and coalition interoperability limitations hindered the support available to the Australian attack. Naval gunfire was not available due to a lack of artillery observers; air cover from the US Army’s 8th Fighter Group could only be provided during daylight hours; and ‘with no air liaison officers, the 2/12th’s air support requests had to be coordinated through the Milne Bay headquarters’.[80] Demonstrating the friction this lack of interoperability caused, ‘when fighter support was expected for one attack, only Japanese aircraft appeared overhead, while a subsequent attack had to be delayed when the US fighters arrived 30 minutes late’.[81] Failing to cut off the Japanese forces as intended, the 2/12th Battalion completed their attack ‘only to find the Japanese had escaped from the island in darkness using two Daihatsu [landing craft] which had been delivered earlier by Japanese warships and concealed from Allied aircraft’.[82] Not only did the lack of interoperability allow the Japanese forces to escape; it may also have resulted in a catastrophic failure had the initial landing been opposed.

Validating the Definition and Tenets

Testing the proposed definition and tenets through the analysis of historical littoral operations offers an opportunity to validate their usefulness as a cohesive framework rather than as isolated considerations. Amphibious operations provide many of the historical lessons for littoral operations; however, they are insufficient on their own to provide the full picture. Like any list of military principles, the proposed tenets for littoral operations are by no means deterministic or final. The imperfect nature of such lists necessitates ongoing refinement driven by further experience. Nevertheless, historical case studies suggest that the proposed definition is valid, and that the five proposed tenets for littoral operations are sufficiently important to the successful conduct of littoral operations to offer a useful starting point. Considered together, the Dardanelles naval campaign, Operation RIMAU, Operation OBOE II, and Operation JACKSTAY demonstrate the impact of the proposed tenets across a wide range of littoral operations.

Failing to Achieve Cross-Domain Mobility, Cross-Domain Effects, and Endurance: The Dardanelles Naval Campaign

The disastrous 1915 Dardanelles naval campaign demonstrated the risks that arise when military operations fail to treat both the land and maritime components of littoral regions as a cohesive space. The campaign sought to separate Turkey from the Central Powers, relieve pressure on the Russians, secure the neutrality of the Balkan states, and enable allied forces to concentrate on the western front.[83] At the beginning of the campaign, Turkish land defences were comparatively weak; ‘if a large military force had then been available, the gallant but appalling events of the landing two months later would never have occurred’.[84] The need to integrate land forces as part of any attempt to seize the Dardanelles was well known. Helmuth von Moltke the Elder had written in 1836 that ‘if artillery equipment were to be arranged in the Dardanelles, I do not believe that any fleet in the world might venture to sail up the strait’.[85] The British Admiralty Foreign Intelligence Committee, General Staff and naval planners had all reached the same conclusion.[86] Nevertheless, when Lord Kitchener suggested that no land forces were available, Winston Churchill elected to attempt a naval operation anyway.[87]

The deliberate decision to attempt to force the Dardanelles using only naval forces undermined any opportunity to achieve effective cross-domain mobility. The only forces able to transition between the sea and land were small Royal Marine and Royal Navy landing parties assigned to vessels within the Allied fleet. Among the members of these ad hoc landing parties was Lieutenant Commander Eric Robinson, who was awarded the Victoria Cross for his efforts to destroy artillery pieces while his white naval uniform drew fire from Turkish defenders.[88] Landing parties relied on small, slow-moving picket boats and cutters to reach the shoreline. Unable to execute anything more than short-duration raids, these landing parties were effectively confined to the maritime domain rather than achieving genuine cross-domain mobility. Despite a small number of limited tactical successes, the landing parties employed in the Dardanelles failed to achieve any operational effect on land and therefore were unable to offset the operational failures of the fleet.

Figure 3: At the water’s edge lies Sapper Fred Reynolds, 1st Field Company Engineers, one of the first to fall on the Gallipoli Peninsula following the failure of the initial attempt to force the Dardanelles in 1915. AWM J03022.

Naval forces attempting to force the strait were unable to generate the cross-domain effects necessary to mitigate the absence of land forces. Naval gunfire alone was insufficient to neutralise the Turkish coastal defences, which in turn prevented the Allied fleet from countering the threat of contact sea mines. Naval guns were largely designed to engage other naval targets through ‘long-range, flat-trajectory fire’.[90] Turkish coastal guns, on the other hand, were specifically designed to engage targets in the maritime domain from their positions on land, thereby achieving cross-domain fires. Significantly enhancing their endurance, the Turkish defences integrated both hardened coastal gun positions and ‘also an assortment of field guns, mortars and howitzers … scattered in the hills and gullies either side of the Strait’[91]. Despite the known risks, the Allied fleet commenced the attack on 19 February 1915, seeking to attrit the coastal defences at long range before closing with their targets to apply decisive fire.[92] A German officer described these engagements:

The fighting on the following days always follows the same pattern: the fleet opens fire from a great distance; the Turkish batteries hold out; the ships draw near; counter-attack by the defenders, withdrawal of the attackers.[93]

These tactics failed to neutralise the coastal defences and instead brought the fleet into range of the Turkish cross-domain effects.

Unable to effectively apply their own cross-domain fires to neutralise the Turkish coastal guns, the attacking fleet instead attempted to employ small landing parties and minesweepers to regain the initiative. Despite these efforts, the structure of the Allied force undermined the endurance necessary to penetrate through the Dardanelles defences. Small landing parties fought to seize and demolish the coastal emplacements; however, they lacked the mass necessary to overcome the well-entrenched and well-supplied Turkish and German defenders.[94] Turkish cross-domain fires quickly sapped the will of the Allied minesweeping crews, highlighting their lack of resilience. Rather than military personnel, minesweepers had been crewed by civilian members of the Royal Navy Reserve Trawler Section; ‘as tough as the trawler men were, not surprisingly, they baulked at the job when they came under fire from the shore guns’.[95] Unable to achieve cross-domain effects or to maintain endurance, the Allied operation culminated on 18 March 1915.

Suffering the combined effects of coastal fires and sea mines:

… the final result of the day’s action was a massive expenditure of shells; the loss of more than 700 sailors; three battleships sunk and three more so seriously damaged … that they would require dockyard repairs.[96]

Having failed to pass through the Dardanelles, the Allied fleet abandoned the original objectives and reverted to a blockade.[97] The fleet not only ‘failed at a huge cost in men, material and national prestige’;[98] it ceded the initiative. German Marshal Otto Liman von Sanders arrived at Gallipoli one week later to lead the further reinforcement of the Turkish defences.[99] The Allies’ inability to achieve the tenets of littoral operations left their attempt to seize the Dardanelles unlikely to succeed, instead unintentionally setting the conditions for their subsequent failure at Gallipoli.

Failing to Achieve Unified C2 and Interoperability: Operation RIMAU

In 1944, a group of British and Australian soldiers from Z Special Unit attempted a daring island-hopping raid to destroy Japanese shipping in Singapore. Although Operation RIMAU was a special operation, the exploitation of both land and maritime domains to manoeuvre through Japanese-occupied territory offers lessons for all littoral operations. The initial plan for Operation RIMAU would see the raiding party transported by submarine to establish an island rear base near their objectives.[100] After capturing a local ‘junk’ vessel to transport the party closer to Singapore, ‘Sleeping Beauty’ motorised submersible canoes would be used to attach limpet mines to Japanese shipping.[101] Finally, the raiding parties would rendezvous at the rear base for submarine extraction.[102] On 11 September 1943 HMS Porpoise departed Garden Island with the raiding party on board, arriving at the planned rear base on Merapas Island on 23 September.[103] On 28 September HMS Porpoise captured the junk Mustika, detaining the crew on board for transport to Australia, and completed the cross-loading of stores.[104] The success of the operation was short-lived. Lacking unified C2 or interoperability, Operation RIMAU failed to achieve its objectives and resulted in the deaths of all members of the raiding party.

On 30 September 1943 the raiding party commenced reconnaissance from islands near their objectives while HMS Porpoise began the return journey to refuel and resupply in Perth.[105] When the submarine docked in Perth its captain, suffering the effects of prolonged stress, resigned his command. An alternative submarine, HMS Tantalus, was rapidly prepared and dispatched as a replacement.[106] In the absence of unified C2, the opportunity to align the priorities of the new submarine’s captain with those of the raiding party was lost. Disaster struck the raiding party on 9 October 1943. As the Mustika sailed between islands, an observation post manned by local auxiliaries identified that the occupants were not indigenous Malays and attempted to board the vessel.[107] With their cover compromised, the raiding party fired on the approaching vessel, scuttled the Mustika and commenced a withdrawal in canoes. Prior to withdrawing, a small party successfully damaged several Japanese ships;[108] however, this limited action failed to achieve the operational objectives and instead intensified the subsequent Japanese pursuit.

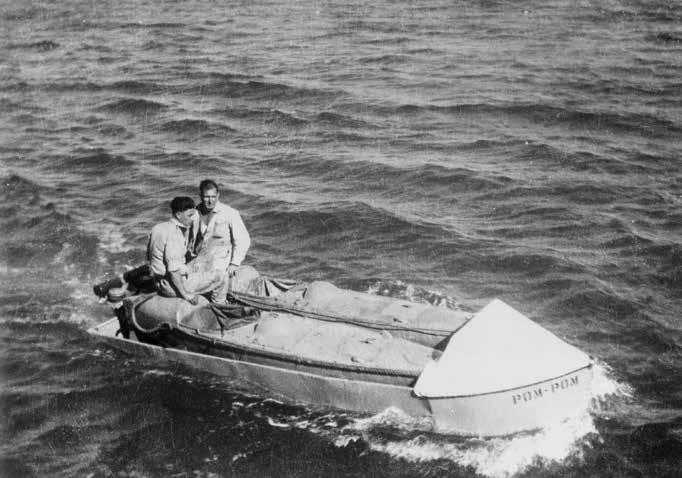

Figure 4: A pair of one-man submersible canoes, known as Sleeping Beauties, are transported during Z Special Unit training. Fifteen Sleeping Beauties were employed for littoral mobility during Operation RIMAU. AWM P01447.001.[109]

Rather than operating under a unified C2 structure, the raiding party and submarine crews relied entirely on cooperation. As a result, the priorities of the naval and land forces diverged, adding friction and additional risk to an already complex operation. This divergence would prove fatal for several members of the raiding party when the captain of the submarine HMS Tantalus elected to seek opportunities to torpedo enemy ships rather than proceeding directly to the planned extraction.[110] Instead of rescuing the remaining survivors at Merapas Island, HMS Tantalus unsuccessfully hunted shipping, unaware that the raiding party had been compromised. By the time HMS Tantalus attempted the rendezvous, the Operation RIMAU raiding party had been fighting to survive for nearly two months. Had the captain of HMS Tantalus seen the raid as central to his mission, rather than as an inconvenience, he would likely have attempted the extraction earlier and with more determination.[111] Further, had unified C2 been in place, the priorities of the land and maritime components would have been aligned, and 18 members of the raiding party would likely have survived.

Once the raiding party was compromised, poor interoperability exacerbated the lack of unified C2 and further undermined any opportunity they had to escape. When HMS Tantalus finally reached the rear base at Merapas, both the captain and the party that went ashore failed to follow the established rendezvous procedures.[112] First, the submarine approached the island from the wrong direction, preventing the raiding party from visually identifying its arrival.[113] Second, the party that went ashore entered the rendezvous point at least an hour after the planned window had closed.[114] Finally, the extraction party made only a single attempt to rendezvous before departing.[115] If the planned procedures had been followed, the 18 members of the raiding party who had successfully reached Merapas would have been rescued. Instead, the submarine departed and left them to the Japanese. While chance had resulted in the detection of the Mustika, a lack of joint interoperability between the raiding party and the submarine crews prevented any chance of the raiding party escaping the Japanese pursuit.

In addition to the lack of joint interoperability, a lack of coalition interoperability further undermined any opportunity for emergency support. Lieutenant Colonel Ivan Lyons, the commander of the raiding party, had experienced US resistance to an earlier raid during Operation JAYWICK, resulting in deliberate efforts to reduce any opportunity for the operation to be cancelled.[116] Rather than employing common cipher keys and tables, Lieutenant Colonel Lyons opted to use a one-off code book that ensured that only his party and the assigned Operation RIMAU cipher clerk could decode the messages. The fact that Lyons left his copy of the code book behind further undermined any opportunity for external communication.[117] Historian Lynette Silver has argued that this was a deliberate act, suggesting that ‘Mary Ellis, Rimau’s cipher officer, believed that Lyon had taken the decision that, come what may, they were not going to be recalled’.[118] While Lieutenant Colonel Lyons’s intent may have been to prevent the US from cancelling his operation, his decisions undermined any opportunity for joint or coalition forces to come to his aid. At the conclusion of Operation RIMAU, all 23 members of the raiding party had been killed in action or were in Japanese captivity, where they would later be executed.[119] By failing to achieve the tenets for littoral operations, Operation RIMAU set the conditions for disaster to ensue once chance undermined the initial plan.

Tenets for Littoral Operations during a Successful Amphibious Assault: Operation OBOE II

Operation OBOE II, the seizure of Balikpapan in 1944, demonstrates the role played by all five of the proposed tenets during the successful conduct of an amphibious operation within the wider context of littoral operations. Operation OBOE II was the final allied amphibious operation of the Second World War, as well as the largest Australian amphibious operation conducted during that conflict.[120] The Australian 7th Division successfully integrated the land, maritime and air domains to seize Klandasan, the most heavily defended of Balikpapan’s beaches.[121] Underpinning that success was the deliberate handover of unified C2 between Rear Admiral Noble as the commander afloat and Major General Milford as the commander ashore ‘and with it the progressive transition of control of air support’.[122] While the air domain was not formally incorporated into the unified C2 structure, a RAAF ‘Air Support Section’ deployed in support of Major General Milford’s headquarters ensured that the air operations were effectively integrated.[123] Through the effective employment of unified C2, the United States Navy, the RAN and the Royal Netherlands Navy commenced the landing operation on 1 July 1945.[124]

Within an hour of the landings commencing, 16,500 members of the 33,000-strong landing force were ashore alongside 1,000 vehicles and were pushing inland through established Japanese defences.[125] Cross-domain mobility enabled the momentum of the inland advance to be maintained. Fifty-one US Army Landing Vehicle Tracked (Amtraks) were employed to bring the forces ashore, with these platforms exemplifying cross-domain mobility through their ability to seamlessly transition between water and land manoeuvre. After transiting from ship to shore, these vehicles enabled the assault to rapidly move inland, leaving ‘the beach clear for subsequent waves of landing craft’.[126] US Army underwater demolition teams working alongside naval minesweepers had prepared lanes through shallow water obstacles ahead of the assault, ensuring that the transition of Amtrak mobility from sea to land would not be disrupted.[127] Initial waves of Amtraks were reinforced by ‘Landing Craft Medium (LCM) and Landing Craft Tank (LCT) carrying vehicles and heavy equipment, followed by Landing Ship Tank (LST) and Landing Ship Medium (LSM), that would unload directly onto the beach’.[128] Through the effective employment of cross-domain mobility, Operation OBOE II rapidly transitioned forces from seaborne transit to inland assault.

Alongside the effective employment of cross-domain mobility, cross-domain effects had both set the conditions for a successful lodgement and supported the maintenance of momentum. Extensive preparatory fire from the air and from the sea targeted the defending Japanese forces with ‘3000 tons of bombs, 7361 rockets, 38,052 rounds of naval gunfire, and 114,000 rounds of automatic weapons fire’.[129] Cross-domain fires continued as the attack progressed, with land, air, and naval fires reinforcing each other to neutralise Japanese coastal defence guns.[130] Equally extensive cross-domain ISR conducted from the air domain provided detailed photographs and scale models of the land domain to support planning and briefing. [131] By achieving extensive cross-domain effects from the air and maritime domains, landing forces were able to seize the initial beachhead in 20 minutes without receiving casualties.[132]

Figure 5: The view looking along Yellow Beach soon after the Operation OBOE II landing at Balikpapan, Borneo, in 1945. DUKW and Landing Vehicle Tracked vehicles are in the foreground. AWM 110385.[133]

On 15 August 1945, the final Japanese defenders at Balikpapan surrendered.[134] Operation OBOE II secured its objectives at a cost of 229 Australians killed, with another 634 wounded.[135] The endurance of the 7th Division during six weeks of fighting through tropical jungle against stiff Japanese resistance was a critical factor in the operation’s success.[136] Effective beachhead management, led by the 2nd Beach Group, assured the sustainment of the attacking forces throughout the operation.[137] Although a significant number of junior officers and soldiers had arrived as reinforcements prior to Operation OBOE II, the level of experience among command teams was ‘unprecedented during the war’.[138] The presence of this core leadership reinforced the resilience of the division and thereby bolstered its ability to maintain endurance. The official history of the operation ‘describes the morale and ethos of a force which believed it was among the world's best fighting forces at the end of a world war’.[139] By achieving the necessary endurance, the 7th Division were able to maintain constant pressure on the Japanese defences until their surrender had been secured.

The success of Operation OBOE II also hinged on extensive interoperability, with joint forces from the US, Australia and the Netherlands enabling extensive fires, rapid troop movement, and effective logistical support. Historian Garth Pratten described Operation OBOE II as ‘the most extensive and well-integrated joint and combined operation undertaken by Australian forces during the war’.[140] In the air domain Air Vice-Marshal Bostock ‘acted as coordinating agency for all pre-invasion strikes and close support’ conducted by ‘the RAAF, US 13th and 5th Air Forces, and naval air units from the US 3rd and 7th Fleets’.[141] In the maritime domain, over 150 ships from three nations formed the Amphibious Task Group, Carrier Covering Group, and Escort Carrier Group.[142] On land, joint forces ensured that the assault force was logistically sustained.[143] The head of the Military History Section at the Australian War Memorial has described Operation OBOE II as ‘an example of the expertise achieved by Australian forces in amphibious operations during the war’.[144] As an amphibious operation within the wider context of littoral operations, Operation OBOE II demonstrates the value of employing cross-domain mobility, cross-domain effects, unified C2, endurance, and interoperability as tenets for littoral operations.

Tenets for Littoral Operations During Successful Riverine Manoeuvre: Operation JACKSTAY

Commencing on 26 March 1966, the US 1st Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment, successfully exploited both the land and maritime components of a riverine littoral environment during Operation JACKSTAY.[145] Operation JACKSTAY sought to disrupt a key Viet Cong sanctuary in an effort to reduce attacks on shipping headed for Saigon via the Long Tau River.[146] The Rung Sat Special Zone characterised the complexity of the littoral environment: consisting of a large tidal mangrove swamp, only one road entered the zone with locals instead relying on the waterways for travel.[147] In addition to inserting land-based blocking positions via air-mobile and surface connectors, Operation JACKSTAY employed six US Navy patrol craft, fast (known as Swift Boats) and nine US Coast Guard patrol boats to prevent Viet Cong reinforcement or resupply via the major waterways.[148] By patrolling the ‘major waterways, which included the Long Tau, the Dong Tranh, and the Soirap Rivers’, these vessels and their land-based counterparts effectively isolated the operational area. Unified C2, exercised first by Captain John D Westervelt as the commander of the Amphibious Task Force, then by Colonel JR Burnett as the commander of the Marine Special Landing Force, ensured that the opportunity presented by this isolation was exploited.[149]

With the blocking positions and riverine patrols in place, the Battalion Landing Team sought to disrupt the Viet Cong within their perceived safe zone.[150] Cross-domain mobility was crucial to the success of the operation; the Marines employed rotary-wing aviation, small boats, amphibious assault platforms, and dismounted movement to exploit the entire Rung Sat Special Zone as manoeuvre space. By effectively manoeuvring on water, on land and through the air the Marine Special Landing Force was able to gain and exploit access to any part of the area of operations, denying the Viet Cong the ability to shield their positions within the complex riverine terrain.

Cross-domain fires supporting the operation included naval fires from the guided-missile destroyer USS Robison, air support from the aircraft carriers USS Hancock and USS Kitty Hawk, and Air Force B-52s launched from Guam.[151] In addition to aiding force protection, fires from the air and maritime domains enabled the land forces to rapidly defeat enemy positions and maintain the momentum necessary to clear objectives dispersed across more than 1,250 square kilometres of tidal mangrove swamp. When Operation JACKSTAY concluded on 6 April 1966, the combined land, maritime and air effects had not only inflicted Viet Cong casualties but had ‘captured and/or destroyed a substantial amount of enemy equipment and material’ at the cost of relatively few US casualties.[152]

Figure 6: US Marines during Operation JACKSTAY, a littoral operation conducted in the riverine Rung Sat Special Zone of Vietnam in 1966. US Naval History and Heritage Command, K-31450.[153]

Reflecting on the success of Operation JACKSTAY, US historian John Sherwood highlights:

For the Navy, these operations represented its first major foray into the rivers of the Mekong Delta and … demonstrated [Military Assistance Command, Vietnam’s] ability to strike at the enemy in a place the Viet Cong originally believed was beyond the control of allied forces.[154]

While the duration of the operation was short, endurance still played a role in securing success. The ability of both ground forces in blocking positions and riverine forces patrolling the major waterways to persist in their assigned areas was essential to establishing the security necessary to find and disrupt the Viet Cong logistical network. Likewise, the resilience of the ground forces operating continuously in a humid swamp was essential to the achievement of the operational objectives. The endurance achieved on land and on the water maintained the isolation of the Viet Cong throughout the operation.

Interoperability was equally important to the success of the operation. Without the integration of the land, naval and coast guard blocking forces, the Viet Cong would likely have exploited the complex littoral terrain to withdraw. Joint forces operated in unison throughout the operation, including M50 Ontos anti-tank vehicles firing from the decks of landing ships, and US Army UH-1 Iroquois helicopters operating from these same platforms to maintain constant air cover.[155] Operation JACKSTAY demonstrated ‘many concepts that would become standard for US forces as the war progressed—namely river assaults, river patrol, and the integration of airpower, ground power, and naval power in a riverine environment’.[156] It also reinforces the utility of the proposed tenets to guide littoral operations where there is a complex overlap between land and water manoeuvre spaces.

Conclusion

As an island nation in a region dominated by archipelagos, Australia requires an ADF that can successfully conduct littoral operations to protect its national interests. The increasing urbanisation of littoral regions and the proliferation of long-range sensors and weapon systems both heightens the importance of littoral operations and increases their complexity. Overcoming these challenges and exploiting the opportunities presented by the littoral environment requires a common definition of what littoral operations actually are. By defining littoral operations as ‘operations conducted in areas defined by the close proximity of the land and sea where the greatest military advantage is achieved by treating land and water as a cohesive, interrelated battlespace’, the ADF can meet this need. This definition incorporates amphibious operations because, while amphibious operations remain important in their own right, littoral operations offer wider options than ship-to-shore actions. Further, this definition is nested within the wider concept of maritime strategy, yet maintains a deliberately narrower focus. By aligning existing littoral definitions with the proposed definition of littoral operations, the ADF can pursue these operations in a manner that is comprehensive and cohesive.

The ADF’s ability to conduct littoral operations can be enhanced by establishing and applying the five proposed overarching tenets. First, cross-domain mobility enables forces to exploit the surfaces and gaps that appear when the littoral environment is approached as a cohesive space rather than a collection of disparate domains. Second, cross-domain effects allow forces to consistently hold adversaries at risk from positions of relative advantage. Third, unified C2 ensures that planning and decision-making occur with the entire littoral environment in mind rather than being constrained by single domain or service thinking. Fourth, endurance enables littoral operations to be conducted despite environmental challenges and the proliferation of modern sensors and long-range weapons. Finally, interoperability ensures that joint and coalition strengths are available to mitigate any weaknesses that would otherwise undermine the conduct of littoral operations. While distilling the complexity of the littoral operations into just five tenets inherently results in imperfections, considered together these tenets are a useful guide to support force design, planning, and decision-making.

The validity of the proposed definition and the usefulness of the associated tenets can be verified through their application to historical littoral operations. The naval operation that sought to penetrate the Dardanelles offered an opportunity to deliver significant strategic outcomes; however, the lack of cross-domain mobility or cross-domain effects, combined with a lack of endurance, rendered the Allied fleet unable to defeat the coastal defences. Operation RIMAU had the potential to deliver a significant blow to Japanese forces in Singapore, exploiting gaps on land and at sea to manoeuvre through a contested environment. However, the failure to employ unified C2 or to achieve interoperability turned poor luck into disaster. By contrast, Operation OBOE II demonstrates the relevance of the definition and tenets in the context of a successful Australian amphibious assault. Finally, Operation JACKSTAY verifies their applicability during riverine operations, demonstrating the reinforcing effects that can be achieved when both land and maritime opportunities are exploited. As these operations demonstrate, clearly and distinctively defining what littoral operations are, then articulating the five overarching tenets that should guide their conduct, will allow the ADF to leverage Australia’s natural alignment with littoral operations.

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this paper was submitted as part of the Marine Corps University Master of Military Studies program. The author would like to thank Dr Lon Strauss, Dr Eric Shibuya, LtCol Khalilah Thomas (USMC), and Ms Andrea Hamlen-Ridgely for their mentorship during the writing of the original paper.

About the Author

Major Matthew Scott has commanded at troop and sub-unit level within 1 Field Squadron, 1st Combat Engineer Regiment. Major Scott has served in staff roles within the 1st Combat Engineer Regiment and Headquarters Defence Force Recruiting and has instructed at the Royal Military College, Duntroon. Major Scott received Bachelor of Laws and Commerce degrees from the University of Queensland, a Master of Strategy and Security degree from the University of New South Wales, and a Master of Military Studies degree from Marine Corps University. Major Scott is currently a student at the USMC School of Advanced Warfighting.

Glossary

Amphibious assault (Australia)—The principal type of amphibious operation, which involves establishing a force on a hostile or potentially hostile shore. For clarity, ADF doctrine does not use ‘assault’ in the context of landings against heavily defended beaches where the risk of casualties is high. The ADF’s approach to this type of operation uses situational understanding, shaping, manoeuvre and surprise to avoid high-risk situations.[157]

Amphibious demonstration (Australia)—A type of amphibious operation conducted for the purpose of deceiving the adversary by a show of force with the expectation of deluding the adversary into a course of action unfavourable to them.[158]

Amphibious operation (Australia)—An operation launched from the sea by a naval and landing force embarked in ships or craft, with the principal purpose of projecting the landing force ashore tactically into an environment ranging from uncertain to hostile.[159]

Amphibious raid (Australia)—An amphibious operation that involves a swift incursion or temporary occupation of an objective in an uncertain or hostile environment, followed by a planned withdrawal.[160]

Amphibious support to other operations (Australia)—An amphibious operation where force elements are established ashore, usually to conduct operations such as disaster relief.[161]

Amphibious withdrawal (Australia)—An amphibious operation involving the extraction of forces by sea in naval ships, landing craft or rotary-wing aircraft from a hostile or potentially hostile shore.[162]

Expeditionary advanced base (US)—A locality within a potential adversary’s weapons engagement zone that provides sufficient manoeuvre room to accomplish assigned missions seaward while also enabling sustainment and defense of friendly forces therein.[163]

Expeditionary advanced base operations (US)—A form of expeditionary warfare that involves the employment of mobile, low-signature, persistent, and relatively easy to maintain and sustain naval expeditionary forces from a series of austere, temporary locations ashore or inshore within a contested or potentially contested maritime area in order to conduct sea denial, support sea control, or enable fleet sustainment.[164]

Land domain (Australia)—Located at the Earth’s surface and sub-surface ending at the high water mark and overlapping with the maritime domain in the landward segment of the littorals.[165]

Littoral (Australia, obsolete)—That area defined by the close proximity of the land, sea and air, where the operational effects of land, sea and aerospace power would overlap.[166]

Littoral (Australia)—The areas to seaward of the coast which are susceptible to influence or support from the land and the areas inland from the coast which are susceptible to influence or support from the sea.[167]

Littoral (UK)—Land that can be directly affected from the sea, and sea that can be directly affected from the land.[168]

Littoral (US)—The littoral comprises two segments of operational environment: 1. Seaward: the area from the open ocean to the shore, which must be controlled to support operations ashore. 2. Landward: the area inland from the shore that can be supported and defended directly from the sea.[169]

Littoral capabilities (Australia)—Capabilities enabling or supporting operations related the littoral zone.[170]

Littoral force commander (US)—A conceptual term, versus a formal title, for the officer who commands all forces within a littoral operations area.[171]

Littoral manoeuvre (Australia)—The use of the littoral as an operational manoeuvre space from which a sea-based joint amphibious force can threaten, or apply and sustain, force ashore.[172]

Littoral manoeuvre (UK)—Exploiting the access and freedom provided by the sea as a basis for operational manoeuvre from which a sea-based amphibious force can influence situations, decisions and events in the littoral regions of the world.[173]

Littoral operations (proposed)—Operations conducted in areas defined by the close proximity of the land and sea where the greatest military advantage is achieved by treating land and water as a cohesive, interrelated battlespace.

Littoral operations (Australia)—Littoral operations are those influenced by the interface between the land and the sea. These can encompass the entire spectrum of operations.[174]

Littoral operations area (US)—A geographical area of sufficient size for conducting necessary sea, air and land operations in order to accomplish assigned mission(s) therein.[175]

Littoral region (UK)—Those land areas (and their adjacent sea areas and associated air space) that are susceptible to engagement and influence from the sea.[176]

Manoeuvre operations in the littoral environment (Australia)—A concept that outlines the conduct of rapid and simultaneous actions by a joint force, to create ‘shock’—a state of command paralysis that renders an adversary incapable of making an effective response. It is the conduct of continuous shaping operations that set the conditions for, and support, the equipment acquisition strategy, decisive actions and transition phases.[177]

Marine littoral regiment (US)—A Marine Corps formation designed to persist within an adversary’s weapons-engagement zone in order to conduct expeditionary advanced base operations in support of fleet operations.[178]

Maritime domain (Australia)—The environment corresponding to the oceans, seas, bays, estuaries, islands, coastal areas, including the littorals and their sub-surface features, and interfaces and interactions with the atmosphere.[179]

Operation (Australia)—A series of tactical actions with a common unifying purpose, planned and conducted to achieve a strategic or campaign end state or objective within a given time and geographical area.[180]

Stand-in engagement capabilities (US)—Low-signature forces designed to accept risk and persist inside a competitor’s weapons-engagement zone to cooperate with partners, support host-nation sovereignty, confront malign behaviour and, in the event of conflict, engage the enemy in close-range battle.[181]

Endnotes

[1] Dayton McCarthy, The Worst of Both Worlds: An Analysis of Urban Littoral Combat (Canberra: Australian Army Research Centre, 2018), pp. 4–11; ‘Enhancing Coastal Resilience During the UN Ocean Decade’, United Nations, updated 3 June 2021, accessed 11 September 2023, https://oceandecade.org/news/enhancing-coastal-resilience-during-the-un….

[2] DJ Killen, ‘Australian Defence’, ed. Department of Defence (Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service, 1976); Kim C Beazley, ‘The Defence of Australia’, ed. Department of Defence (Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service, 1987); Robert Ray, ‘Defending Australia’, ed. Department of Defence (Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service, 1994).

[3] Killen, ‘Australian Defence’; Beazley, ‘The Defence of Australia’; Ray, ‘Defending Australia’.

[4] John Moore, ‘Defence 2000: Our Future Defence Force’, ed. Department of Defence (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2000); Joel Fitzgibbon, ‘Defending Australia in the Asia Pacific Century: Force 2030’, ed. Department of Defence (Canberra: Defence Publishing Service, 2009).

[5] Stephen Smith and Angus Houston, ‘National Defence: Defence Strategic Review 2023’ (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2023); Marise Payne, ‘2016 Defence White Paper’, ed. Department of Defence (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2016); Scott Morrison and Linda Reynolds, ‘2020 Defence Strategic Update’, ed. Department of Defence (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2020); Linda Reynolds, ‘2020 Force Structure Plan’, ed. Department of Defence (Canberra: Defence Publishing Service, 2020); ‘Army’s Transformation’ Australian Army website, 2023, accessed 13 March 2023, at: https://www.army.gov.au/our-work/armys-transformation.

[6] David H Berger, Force Design 2030, United States Marine Corps (Washington, DC, 2020), p. 2.

[7] Milan Vego, ‘On Littoral Warfare’, Naval War College Review 68, no. 2 (2015): 30.

[8] Angus J Campbell, ‘ADF-C-0 Foundations of Australian Military Doctrine’ (Canberra: Lessons and Doctrine Directorate, 2021), Ch 2.

[9] Director General Training and Doctrine, ‘LWD 3-0 Operations’ (Puckapunyal: Australian Army, 2018), Ch 4.

[10] Angus Campbell, ‘ADDP 3.2 Amphibious Operations’ (Canberra: Joint Doctrine Directorate, 2019), Ch 4.

[11] See Glossary.

[12] United States Marine Corps Headquarters, ‘Tentative Manual for Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations’ (Washington, DC: Department of the Navy, 2021).

[13] AT Mahan, The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660–1783 (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1890), p. 6

[14] Ibid., p. 374.

[15] Julian Stafford Corbett, Some Principles of Maritime Strategy (London, New York: Longmans, Green and Co., 1911), p. 11.

[16] Ibid., p. 13.

[17] Ibid., p. 14.

[18] William L Rodgers, ‘Marathon, 490 B.C.’, in Merrill L Bartlett (ed.), Assault from the Sea: Essays on the History of Amphibious Warfare (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1993).

[19] Andrew Young, ‘Amphibious Genesis’, in Timothy Heck and BA Friedman (ed.), On Contested Shores: The Evolving Role of Amphibious Operations in the History of Warfare (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps University Press, 2020), pp. 38–39; Thomas More Molyneux, Conjunct Expeditions, or Expeditions that Have Been Carried on Jointly by the Fleet and Army: With a Commentary on a Littoral War (R and J Dodsley, 1759).

[20] Molyneux, Conjunct Expeditions, p. 3.

[21] Ibid., pp. 3–4.

[22] Young, 'Amphibious Genesis', p. 43.

[23] Molyneux, Conjunct Expeditions, pp. 3-4; Young, 'Amphibious Genesis', p. 39.

[24] Department of Defence, ‘Photograph S20221586’ (Australia, 2022), at: http://images.defence.gov.au/220801-M-AL123-1351.jpg.

[25] USMC and US Navy, ‘Littoral Operations in a Contested Environment’ (Virginia: Department of the Navy, United States of America, 2017), p. 6.

[26] Ibid., p. 3

[27] Ibid., p. 4.

[28] Royal Navy, ‘Maritime Operating Concept’ (UK Ministry of Defence, 2022), p. 38.

[29] Secretary of State for Defence, ‘Defence in a Competitive Age’ (UK Ministry of Defence, 2021), p. 48.

[30] Royal Navy, ‘Maritime Operating Concept’, p. 55.

[31] Concepts and Doctrine Centre Development, Joint Doctrine Publication 0-10 UK Maritime Power, 5 (Shrivenham 2017); See Glossary.

[32] Concepts and Doctrine Centre Development, 'Joint Doctrine Publication 0-01.1 UK Terminology Supplement to NATOTerm' (Shrivenham 2022).

[33] McCarthy, Worst of Both Worlds, p. 10.

[34] Ibid., p. 11.

[35] See Glossary.

[36] See Glossary.

[37] See Glossary.

[38] Department of Defence, 'Australian Defence Glossary' (Canberra 2022).

[39] See Glossary.

[40] Land Commander Australia, ‘Land Warfare Doctrine 3-0-0, Manoeuvre Operations in the Littoral Environment (Developing Doctrine)’, ed. Land Warfare Development Centre Doctrine Wing (Puckapunyal, 2004), p. xix.

[41] Selection and maintenance of the aim, Concentration of force, Cooperation, Offensive action, Security, Surprise, Flexibility, Economy of effort, Sustainment, and Morale (Campbell, ‘ADF-C-0 Foundations of Australian Military Doctrine’, Ch 2).

[42] Focusing friendly action on the adversary centre of gravity, Achieving surprise, Identifying and prioritising a main effort, Utilising deception, Reconnaissance pull, Operational tempo, Combined arms teams, and Application of joint fires and effects (Director General Training and Doctrine, ‘LWD 3-0 Operations’, Ch 4).

[43] George EP Box, ‘Robustness in the Strategy of Scientific Model Building’, in Robustness in Statistics (Elsevier, 1979).

[44] David H Berger, Force Design 2030 Annual Update May 2022, (Washington, DC: United States Marine Corps, 2022), pp. 5–8.

[45] Chris Field, Testing the Tenets of Manoeuvre: Australia’s First Amphibious Assault Since Gallipoli: The 9th Australian Division at Lae, 4–16 September 1953, Land Warfare Studies Centre Working Papers 139 (2012), p. 3.

[46] Ibid.

[47] David Dexter, The New Guinea Offensives, vol. 6 (Australian War Memorial, 1961), p. 363.

[48] Field, Testing the Tenets of Manoeuvre, pp. 11–12.

[49] Ibid.

[50] Ibid., p. 24.

[51] David H Berger, ‘Preparing for the Future Marine Corps Support to joint Operations in Contested Littorals’, Military Review 101, no. 3 (2021): 9.

[52] USMC and Navy, ‘Littoral Operations in a Contested Environment’, p. 16.

[53] Jacopo Pessina, ‘An Amphibious Special Operation: The Night Attack on Porto Ercoletto, Tuscany, 2 June 1555’, in Timothy Heck and BA Friedman (eds), On Contested Shores: The Evolving Role of Amphibious Operations in the History of Warfare (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps University Press, 2020), p. 9.

[54] Ibid., p. 22.

[55] Ibid.

[56] Ibid., pp 9–10.

[57] Vego, ‘On Littoral Warfare’, pp. 31–63.

[58] USMC and Navy, ‘Littoral Operations in a Contested Environment’, p. 9.

[59] See Glossary.

[60] W Kent Hackmann, ‘The British Raid on Rochefort, 1757’, The Mariner's Mirror 64, no. 3 (1978): 263.

[61] David Syrett, ‘British Amphibious Operations during the Seven Years and American Wars’, in Merrill L Bartlett (ed.), Assault from the Sea: Essays on the History of Amphibious Warfare (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1993), p. 62.

[62] Syrett, ‘British Amphibious Operations’, p. 62.

[63] BA Friedman, ‘Naval Strategy and the Future of Amphibious Operations’, in Timothy Heck and BA Friedman (eds), On Contested Shores: The Evolving Role of Amphibious Operations in the History of Warfare (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps University Press, 2020), pp. 357–359.

[64] Berger, ‘Preparing for the Future Marine Corps Support to joint Operations in Contested Littorals’, p. 8.

[65] David H Berger, ‘Sustaining the Force in the 21st Century: A Functional Concept for Future Installations and Logistics Development' (Quantico, VA: United States Marine Corps, 2019), p. 2.

[66] McCarthy, Worst of Both Worlds, p. 28.

[67] Edgar O’Ballance, ‘The Falklands, 1982’, in Merrill L Bartlett (ed.), Assault from the Sea: Essays on the History of Amphibious Warfare (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1993), pp. 380–385.

[68] Richard C Dunn, Operation Corporate: Operational Artist's View of the Falkland Islands Conflict (Pickle Partners Publishing, 2014), p. 15.

[69] Martin Middlebrook, Argentine Fight for the Falklands (South Yorkshire: Pen and Sword, 2003), p. 57.

[70] Ibid., p. 70.

[71] Ibid., pp. 72–73.

[72] Vego, ‘On Littoral Warfare’, p. 48.

[73] McCarthy, Worst of Both Worlds, pp. 45–46.

[74] Vego, ‘On Littoral Warfare’, pp. 30–49.

[75] McCarthy, Worst of Both Worlds, p. 61.

[76] Ibid., p. 46.

[77] Tim Gellel, ‘From Goodenough to Outstanding: Army's Mastery of Amphibious Operations Between 1942–1945’, Australian Army Journal 14, no. 1 (2018): 84.

[78] Ibid., p. 84.

[79] Ibid., p. 85.

[80] Ibid.

[81] Ibid.

[82] Ibid., p. 86.

[83] Henry Woodd Nevinson, The Dardanelles Campaign (Nisbet & Company, Limited, 1920), p. 9.

[84] Ibid., p. 47.

[85] Erich Prigge, The Struggle for the Dardanelles: The Memoirs of a German Staff Officer in Ottoman Service (South Yorkshire: Pen and Sword, 2015), p. 137.