If a military force and its leaders have failed to prepare themselves and their forces with honesty, imagination, and a willingness to challenge fundamental concepts, then they will pay a dark price in the blood of their sailors, soldiers, marines, and airmen.

Williamson Murray, ‘US Naval Strategy and Japan’[1]

[W]hat people think cannot be separated from the question of how they think.

Azar Gat, A History of Military Thought[2]

Introduction

Australia’s geopolitical circumstances are changing.[3] The above quotations have an implied question for Australia: is the Australian Defence Force (ADF) also preparing for the changing environment? Many commentators focus on the need to change capabilities, equipment and structure to address this evolving environment. Often, such commentary lacks grounding in wider military theory, history, and strategic culture.[4] These statements have many similarities with the calls made by technology proponents of the interwar period.[5] Interestingly, the British Army of the interwar and early Second World War period was one of the most mechanised armies of the time. Yet its military thinking had not matured.[6] An example was British armoured culture, which continued to favour cavalry-style charges as ‘they could do the same when they had exchanged their horses for tanks’.[7] Such thinking highlights a critical point: the push for technological advantage is important, but such an advantage is wasted without commensurate growth in military thinking. The Germans’ interwar developments, education and wargaming illustrate how such growth provides a military edge.[8] However, the German approach focused only on the tactical and operational levels of war.[9] A better example is the United States, whose approach to education, training and development produced a military that:[10]

… without a preponderance of resources, without superior aircraft or ships, and with a mixed assortment of experienced and inexperienced ground troops … challenged the Imperial Japanese war machine at the zenith of its power and [came] out on top[.][11]

Many scholars highlight how US interwar wargaming was a major contributing factor to US in-war success.[12] Such gaming helped develop a culture of ‘learning-to-learn’ within the US military. Gaming contributed to developing a US officer corps that accepted, integrated and used a wide range of views, alternative approaches and schools of thought to frame and solve the problems of war.[13] These dispositions are called a pluralist habit of mind. Such a habit of mind enables military professionals to adapt training and capability to meet changing circumstances.[14] Several scholars explain how wargaming provides ‘a shared experience’ that strengthens knowledge and builds these strong habits of mind.[15] Even as early as the 19th century, wargaming was seen to develop ‘studious and industrious habits … essential and indispensable to those invested with high command’.[16] This article outlines how gaming helps grow these important habits by enhancing the mental skills that underpin decision-making, and expanding the mental models used in decision-making.

This article argues that a culture of deliberate professional gaming helps develop a military’s intellectual edge. Deliberate professional gaming is where people actively choose to play and practise games to enhance professional development and education. A key element of such a culture is an acceptance of, and willingness to use, games. Wargaming is an example of professional military gaming. To explain how gaming supports the profession of arms and decision-making, the article first summarises the foundation of human decision-making: the heuristic. With this understanding, the article identifies the similarities between human heuristics and the Military Appreciation Process (MAP). Recognising these similarities allows the article to highlight how gaming provides two cognitive outcomes. First, games can enhance the mental skills that underpin decision-making. Second, games can help build new mental models for military officers. New mental models help increase professional creativity in decision-making. Combined, both benefits enhance military planning and decision-making. Yet contemporary Western militaries rarely use gaming to enhance military thinking. Given the benefits games may provide, the article proposes that the military should adopt a culture of deliberate and professional gaming. To assist, the article suggests some approaches to introduce professional gaming within military education. As the scholars cited earlier indicate, gaming within education helps build a pluralist habit of mind and enhances military planning, decision-making, and thinking about competition, conflict and war.

Understanding Decision-Making: The Heuristic

Before discussing how gaming can enhance decision-making, it is first helpful to understand how humans make decisions. Studies indicate that human decision-making is founded on a range of specific mental tools known as ‘heuristics’.[17] As part of a major study into heuristics led by Gerd Gigerenzer and Peter Todd, researchers identified how heuristics (sometimes referred to as intuition) are not designed for optimal decision-making.[18] Instead, these tools help produce practical solutions while also reducing cognitive load:[19]

In the real world, a good decision is less about finding the best alternative than finding one that works … our minds like our bodies have been shaped by evolution: we have inherited ways of thinking from those of our ancestors whose mental tools were best adapted for survival and reproduction. … our mental tools are fast and frugal. They allow us to make decisions based on very little information using simple rules … Although they apply to different sorts of problems, heuristics have a common structure, which arises from the way humans make decisions. First, we search the environment for information, or cues, upon which to base a choice. A heuristic contains rules that direct the search. Next, we must stop searching. It’s pointless trying to find out everything there is to know about a nut or berry if we starve in the process. Heuristics contain a stopping rule, often ending the search after only a few cues have been considered. Finally, we must make a choice—eat, run, mate, attack.[20]

The mental tool described above helps reduce cognitive load by leveraging human knowledge, experiences and memory.[21] The more experiences there are, the more options there are. This cognitive load reduction is essential, as high cognitive loading is energy intensive and can quickly tire a person. Research into heuristics explains how these mental tools process, evaluate, modify and determine the best course of action based on previous experiences and knowledge.[22] This research also highlights the broad framework these heuristics follow.

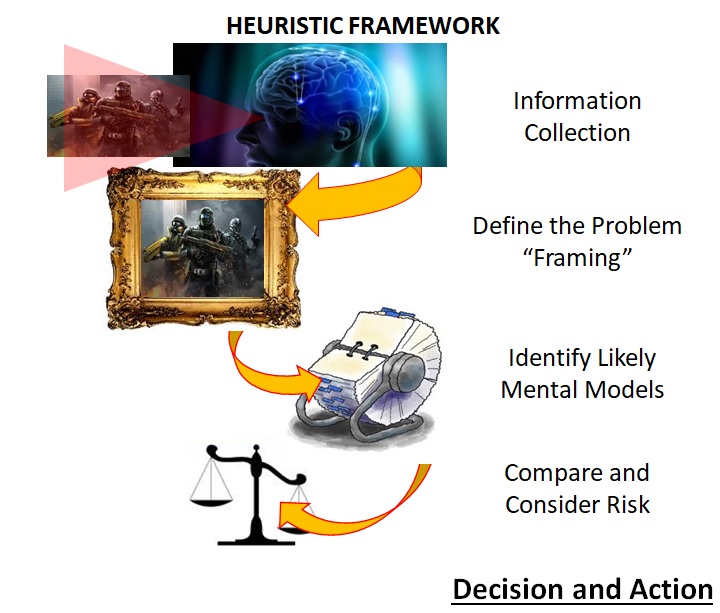

Generally, there are five steps to a heuristic (Figure 1).[23] Although each heuristic is used for different decision-making situations, they all follow this broad framework. As described above, the first step in the heuristic framework is collecting information from the senses. This information forms the environmental context. Leveraging this information, the framework attempts to figure out, or frame, what the problem is. This part of the process is vital for two reasons. First, defining the problem directs which specific heuristic should be actioned. Second, this problem frame guides the heuristic’s search for past experiences and knowledge. Using this problem frame, heuristics start looking for previous experiences that have similarities to the current situation.[24] These experiences are summarised through a person’s mental models.

Figure 1. The Heuristic Framework Overview (pictures from image commons and clip art)

The third step of the heuristic framework is to match the current situation and problem frame to any relevant mental models the person holds. Mental models are ‘deeply ingrained assumptions, generalisations, or even pictures or images that influence how’ an individual (or a group) understands theories, concepts and the real world.[25] As this article discusses later, these mental models are based on previous physical or pedagogical experiences.[26] No matter where the experience comes from, mental models shape a person’s knowledge of how things work, and their perceptions of why things operate in a particular manner.[27] As such, mental models directly influence decision-making.[28] Heuristics seek to find models that relate to the current problem frame.[29] In essence, the heuristic ‘scrolls’ through the mind’s models much like a person would scroll through an old Rolodex.[A] It is worth noting that the number and breadth of mental models can also shape a person’s potential for creative decision-making.[30] Once this step has selected a range of applicable mental models, the heuristic starts to compare and modify them for the situation at hand.

Using identified mental models, the heuristic commences the fourth step of the framework: comparison. The number of mental models identified depends on a range of factors, such as the heuristic in use, the situation, and the individual’s knowledge. On average, heuristics select five to seven models to compare. Research highlights that human brains can simultaneously manage five to seven concepts. Each ‘concept’ represents a single idea: a person, an abstract theory, an identified obstacle on a route, a mental model.[31] Although this concept ‘limit’ has implications for other areas of human interaction—spans of command, deception, information management, military warfighting concept writing—within the heuristic, this limit helps focus problem-solving. Of course, the ‘five-to-seven rule’ assumes that a person holds more relevant experiences and mental models than this limit. Where a person’s knowledge and experiences amount to less than five, the heuristic takes what mental models are available, even if that number is one.

Using the collected mental models, the heuristic compares each model to the current situation. In essence, the brain figures out the costs and benefits of the different solutions, and gauges the possible risk. It is worth noting that the mind already has a series of tools to gauge probability and likelihood.[32] Through this process, mental models are short-listed or discarded back to memory as required, leading to the final one or two mental models for consideration. These final models are then sent to the prefrontal cortex for the hard part: decision.

The decision step of the heuristic framework is the most energy-intensive aspect of the process. Based on the comparison, the frontal brain attempts to adjust the final few mental models to the situation. The closer the best-fitting mental models are to the situation, the less effort required and less energy expended. However, where there were few mental models for the heuristic to work with, the prefrontal cortex is required to modify the mental model significantly. In the worst case, where there are no mental models, the brain must build a solution to the problem from scratch.[33] Such brain activity is intensive and is why a person ‘feels tired’ after dealing with a significantly challenging problem for the first time. This is why a platoon-level tactical exercise without troops (TEWT)[B] is more tiring and demanding for a staff cadet[C] or lieutenant than for a major or lieutenant colonel: greater experience leads to more mental models and options for the heuristic and prefrontal cortex.[34] The ease of decision-making that comes with experience is not the only similarity between the heuristic and military planning.

Understanding Military Planning: A Heuristic Decision Cycle

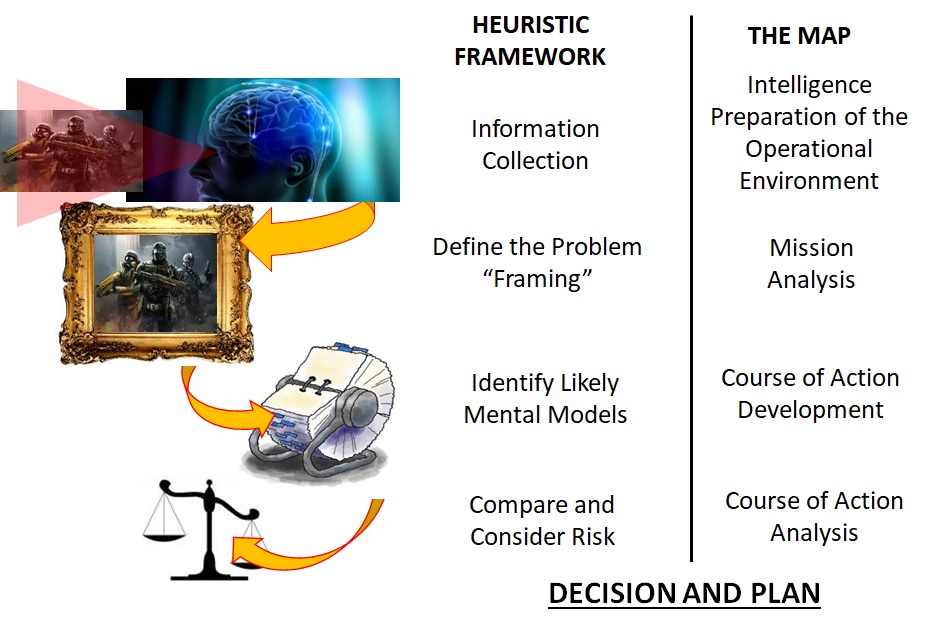

Recent ADF doctrine acknowledges the link between the heuristic framework and how militaries plan.[35] The similarities between the heuristic framework and the MAP are seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The Heuristic Framework and the Military Appreciation Process

Given the links seen in Figure 2, ADF doctrine (ADF-P-5) makes the following statements:[36]

- The MAP, as an activity of the mind, mimics the heuristic framework.

- Like the heuristic, the MAP provides a structured framework to think about, frame and solve problems.

- By mimicking the heuristic, the MAP slows the heuristic process, forcing military planners to write down and explain their mental models.

- Therefore, ‘the MAP makes professional military thinking, driven by heuristics, explicit’.[37]

Scholars highlight that by making mental models and the heuristic process explicit, people can explain their assumptions and worldviews.[38] Such a process helps build shared understanding and better decision-making. It also helps planners test and adjust their mental models, leading to learning.[39] Of course, this assumes people use the planning process, even a modified one, and do not just ‘situate the appreciation’!

The discussion on heuristics and planning allows one to infer that helping to build people’s heuristics and mental models will enhance individual and collective military planning. The first step in enhancing military planning is to increase the capacity of the mental skills that underpin the heuristic: pattern identification, pattern matching, and risk analysis.

Enhancing Decision-Making Capacity: Exercising Mental Skills

In 2021, the US Marine Corps introduced chess as a part of their recruit and infantry training programs. Students played chess both as part of the course and as a pastime. The game was a hit (partly because all mobile phones were banned).[40] Furthermore, instructors were surprised by the increased mental development and decision-making skills of the Marine trainees, with one instructor saying:

These students are performing at a level [of] … senior Marines [who have] come back from their first deployment. Some of [the trainees] are able to make the same calls as team leaders in the Fleet Marine Force … [I]t’s crazy to see them developing as students, because they’re thinking about things instead of just being another guy in line.[41]

In every chess game, players have a finite number of options to move their pieces. These options reduce in the later stages of the game. The player who can identify the patterns of likely moves, including their opponent’s likely actions, and match those patterns with possible chess solutions is more likely to win. Chess is an illustrative example of how identifying and matching patterns is a crucial skill within heuristic decision-making.

There are many studies on the cognitive benefits of chess.[42] These studies indicate that deliberately playing—or actively choosing to play and practice—chess does, over time, increase a person’s general problem-solving and critical thinking skills.[43] Specifically, studies highlight that playing chess enhances an individual’s capacity to identify and match patterns.[44] Such enhancements speed up a person’s capacity to frame a problem, identify likely mental models that may assist their decision-making, compare possible solutions, and assess risk. In effect, deliberately playing chess helps speed up a person’s decision-making and mental capacity.[45] Here, chess acts as a vehicle to hone the brain’s pattern identification and matching skills. However, chess is not the only game that can do this. There are a wide variety of games whose mechanics directly tap into, and enhance, the brain’s pattern-matching potential. Such games are probably being played by soldiers, sailors and aviators at local game stores on Wednesday and Friday nights.[46]

Customisable card games, such as Flesh and Blood and Magic: The Gathering, require players to recognise patterns. Based purely on the opponent’s played cards, a player must answer a series of questions. First, a player needs to estimate the likely cards in an opponent’s deck. Next, the player should attempt to discern their opponent’s game strategy, and what the opponent is likely to do next. Finally, the player must adjust their strategy to win the game. These questions can only be answered based on a player’s knowledge and pattern identification and matching skills. This pattern identification and matching starts the moment the first card is played. Furthermore, unlike chess, drawing cards leads to a degree of randomness. Such randomness further tests and stresses a player’s matching capacity. Stressing these skills is similar to exercising a muscle.[47] Increasing these mental skills also enhances the brain’s capacity to calculate risk.

Military decision-making requires judgements on risk. Military risks are dynamic and changing. In such situations, it is often a military professional’s knowledge and innate capacity to judge cost and benefit that informs decision-making.[48] Building on pattern identification and matching, the heuristic has a set of tools (specifically known as the availability heuristic) to assist with such risk analysis.[49] Yet it is difficult for the military to enhance such a skill. Although TEWTs and military courses allow officers to understand capabilities, these approaches rarely provide ‘post-H-Hour’ situations to enhance risk understanding and decision-making. Furthermore, military exercises and simulations can be expensive and time-consuming, and often include a range of perceived biases on ‘blue force potential’.[50] However, much like pattern identification and matching, games can exercise the mental capacity needed to understand and assess risk, thereby enhancing these skills for general decision-making.[51] Games also cost less.

Gamers constantly make mental judgements on cost versus benefit. Discarding a card, sacrificing a piece, or throwing a squad token at the opponent to screen friendly forces in a wargame are all forms of cost-benefit analysis. In each case, the gamer has assessed that their longer-term plan outweighs the advantage they just awarded their opponent. Making such judgements is a key part of any competitive game. It is also important in ‘cooperative games’, such as Pandemic, Castle Panic or Marvel Champions. In these games, players work together to overcome the game’s challenges. However, unlike competitive games, cooperative games provide a more exciting dynamic for risk analysis, understanding, and judgement: a player’s analysis affects themselves and the entire team. Furthermore, these games often allow for ‘table talk’, or a discussion between players on what to do next.[52] These discussions, coupled with the game’s mechanics and theme, often create a more social and immersive experience for players. As academic research highlights, such immersive and social interactions create a better environment for skill learning and development.[53] Many of the games listed above are relatively quick—playable during a lunch break. They are also immersive, either through their high levels of competition or the cooperative theme. The quick playtime and immersive nature mean these games can provide multiple ‘reps’ of mental stimulation, growing mental skills in a similar fashion to a regiment’s morning physical training sessions.

The above discussion highlights how deliberatively playing games can improve the mental skills that underpin human decision-making: pattern identification, pattern matching, and risk analysis. Developing these mental skills helps enhance a person’s capacity to frame a problem, identify possible solutions, compare those solutions to the situation at hand, and understand the risks involved. However, the employment of these mental skills relies on a library of experiences. Military professionals rely on mental models when developing courses of action in planning, or making decisions during periods of stress and danger. Further, having a wide variety of mental models helps military professionals be more creative in their decision-making.[54] Therefore, speed in cognition is wasted without a wide array of mental models to call on. Luckily, games can also help build mental models.

Enhancing Decision-Making Knowledge: Growing Mental Models

Admiral Nimitz, commander of Allied forces in the Central Pacific during the Second World War, once stated:

The war with Japan had been enacted in the game rooms at the War College by so many people and in so many different ways that nothing that happened during the war was a surprise … except the kamikaze tactics toward the end of the war. We had not visualized these. [55]

Ed Millar’s seminal work War Plan Orange reinforces Nimitz’s statement. War Plan Orange was the United States war plan to defeat Japan. Throughout the interwar period, the war plan informed a range of military actions: capability development, exercises, and the wargame scenarios of the US Naval War College and Marine Corps War College.[56] Indirectly, War Plan Orange also influenced US Army War College war gaming. Army wargaming led to the vital Rainbow Plans: the US plans to defeat Germany and Japan.[57] The structure, development and use of these war plans is similar to today’s warfighting concept development and usage. Much like the war plans, contemporary warfighting concepts (good and bad) provide a vision for military power and outline how it may be employed.[58] The US interwar wargaming was conducted in a free-rein and open manner. Scholarly research highlights how this free-play, or unrestricted, wargaming, coupled with challenging and academically diverse education, informed US military officer thinking about, planning for, and conduct of the Second World War.[59] As Nimitz implies, these wargames helped shape the mental models held by US military officers.

An immersive and challenging situation is key to creating or changing mental models. A challenging situation can be a difficult undertaking, a situation that confronts previously held views and beliefs, or both.[60] The experiences necessary to modify or build new mental models occur in two ways. The first is physical, where a person directly experiences something and internalises it. Militarily, such experiences are often generated through existing training systems, exercises and courses. These experiences relate to knowledge of how to do something, or procedural knowledge.[61] The second method is to provide a challenging experience that simulates real-world experiences. Demanding education, such as that provided at a Staff or War College, can provide such experiences.[62] This style of experience often changes how a person views the world, modifying their understanding of why things work and what outcomes can be achieved. Such knowledge, known as propositional knowledge, directly influences a person’s understanding of theory.[63] This style of knowledge also helps drive creativity in decision-making.

Creative decision-making is supported by having a wide variety of mental models. Such variety helps military professionals understand different ways of adapting theory to practice. This allows a person to modify procedural knowledge for the situation at hand. Militarily, the capacity to be creative—to change tactics, change procedures and think on the fly—is a critical part of achieving military advantage. Research indicates that deliberately playing games can provide the mentally challenging experiences necessary for new and varied mental models.[64]

A game is a representation of real-world concepts.[65] Games help create new ways to think and see things.[66] Until the mid-20th century, most Western militaries understood that games helped simulate real-world decision-making.[67] Wargames are an illustrative example. They allow military professionals to apply the theory of war, thereby building a better understanding of theory in practice. To achieve this outcome, games must provide an immersive experience.

To be immersive, a game requires four key elements. The first is that games should be real-time play between players.[68] Next, games should provide a useful representation of the type of decision-making required. Games do not have to perfectly represent the real world, only the key elements needed to simulate decision-making within an environmental context.[69] Diplomacy is a well-known game that simulates geopolitical thinking.[70] Yet games do not have to be ‘wargame-like’ to provide a benefit. For example, Sheriff of Nottingham is a fun and engaging game focused on bluffing and negotiation. Much like Diplomacy, the game may help people understand the decision-making and theories of mind necessary for successful information operations, negotiation, and diplomacy.[71] However, such games do not help in simulating resource management or combat decisions. The board games Dune Imperium and The Expanse, where players are one of the factions in each franchise, may provide stronger strategic decision-making experiences due to theme, abstract combat, and resource management.

Another requirement for an immersive game is for it to be pitched at an appropriate level: tactical, operational or strategic (and grand strategic). The games mentioned above may assist strategic thinking but would be poor representations of operational or tactical decision-making. Finally, games need to be ‘free-play’, or unrestricted in nature. Such games often have a scenario, starting forces/resources, and rules. However, each player’s plan is not constrained beyond these starting limitations and may change throughout the game. These unrestricted wargames were the norm during the interwar period.[72] This unrestricted gameplay allows players to engage with, experience and learn from the decision-making ‘simulation’ that the game represents. For the military, such games are not limited to tactical wargames. Military theory is expansive, extending from strategic theory to tactical understanding.[73] Therefore, gaming should also be expansive. As already alluded to, the US military of the interwar period is an illustrative example of successfully employing wargames across the strategic, operational and tactical spectrum.[74]

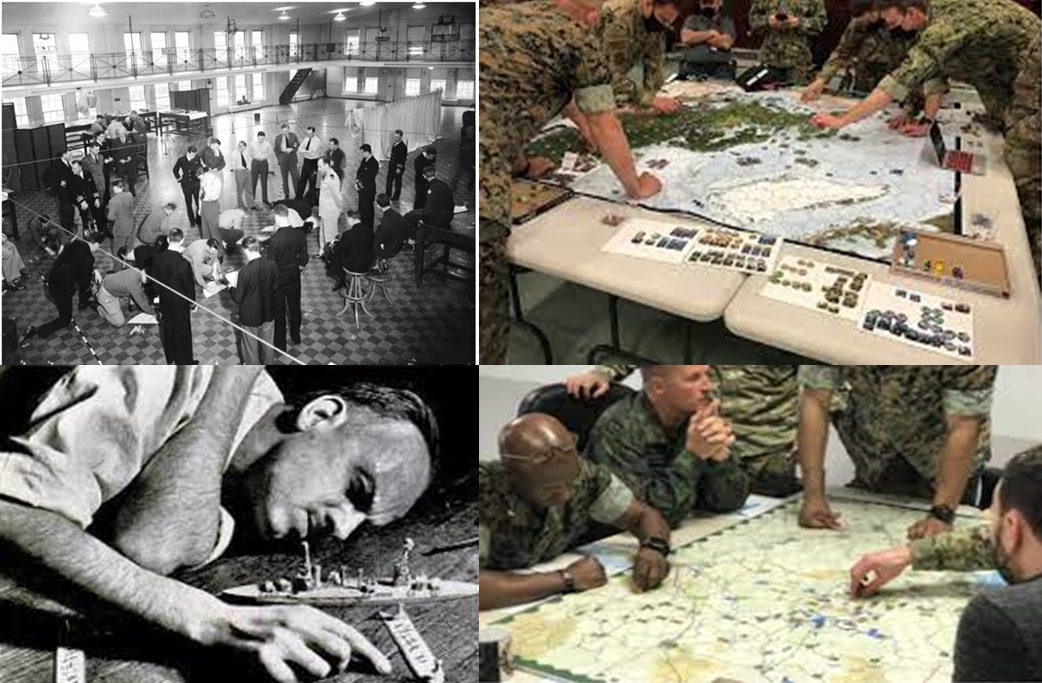

During the interwar period, US strategic wargames focused on allowing students to develop their strategic thinking. Often these wargames looked more like a syndicate discussion over a map (Figure 3). Students would take sides, argue and debate their case, and the instructors would facilitate the discussion and decide who won. In modern parlance, this style of game is known as a matrix game, or syndicate game. In such games, one side takes action and argues their case. The other side then outlines any problems (or rebuts) and then states how they react. Each turn is adjudicated.[75] Such games appear similar to the MAP’s Course of Action Analysis wargaming. However, the turns and decisions of players are unstructured. There is no ‘plan’ that must be ‘tested’, constraining player thinking. This style of gaming is still used today in many professional areas.[76] In the US interwar context, such games helped students understand strategy and place military operations within context.

Figure 3. Strategic War Gaming. US War College strategic wargame set-up (left) and contemporary versions of matrix games (right)[77]

Inter-war period US wargaming often linked operational and tactical games. The effects at the operational level would have flow-on effects in subsequent tactical games. Such flow could also go backwards. Operational wargames were typically tabletop games. They focused on campaigns, finding the enemy, and understanding the enemy’s capabilities. Logistics management, fleet orders, and similar issues were all given abstract rules to help game management and facilitate decision-making. To create further uncertainty, instructors would draw playing cards and refer to a corresponding ‘strategic effects’ list. The ace of spades might represent another nation entering the war, changing how students thought about the problems of war. Meanwhile, another card might represent economic changes affecting logistics. Dice created internal friction and uncertainty: Did the weather affect the fleet? Did the message get received in time?[78] In many ways, these games are similar to contemporary ‘strategy’ board games available at hobby stores, or the game Assassin’s Mace used by the US Marine Corps to explore operational thinking.[79] Inter-war tactical wargames looked very similar to modern miniature wargaming. Miniatures represented ships, planes and land units; distances were measured; and movement and terrain rules were used (Figure 4).[80] These tactical wargames represented the science of war in action. Such games helped officers understand the realities of tactical decision-making, military capabilities, and different ways to tactically respond in combat.[81] However, the theory of war is not the only theory the profession of arms should understand.

Figure 4. Operational and tactical war gaming. Historical operational (left top) and tactical (bottom left) wargaming and contemporary US Marine Corps Assassin’s Mace operational wargaming (right)[82]

Military theory often relates to other topics such as human nature (and philosophy), international relations, broad economics, and political power.[83] Yet it is difficult for military officers to experience such issues directly. Without some means of developing relevant experience, military professionals may, at best, only have a purely theoretical understanding of these topics. Worse, military officers may not develop experience in these other areas of national power until they reach senior rank. The above discussion has implications for career management.[84] Nevertheless, gaming may provide an inexpensive and easily accessible way of building some experiences in these areas. A range of board games—fantasy, science fiction and historical—directly tap into the decision-making space seen within international relations, economics and politics. Some historical games relevant to contemporary great power contestation are:[85]

- Pericles—a wargame that allows players to play out the diplomatic, economic and military actions that lead up to, and occur within, the Peloponnesian War[86]

- Churchill—a game about coalition politics, economics, and military action. The game focuses on the Second World War and Churchill’s attempts to influence the Allies into the ‘Germany First’ strategy

- Twilight Struggle—a two-player game where players are the United States or the Soviet Union over the period 1950 through to 1989. Players use a range of national tools to influence the world and achieve dominance in the Cold War.

The above games do not model all geopolitical circumstances of the time. However, they are useful for several reasons. First, they are available through civilian game stores. As ‘hobby games’, they are designed to be played without a trained facilitator (or game master). Furthermore, these games provide helpful insights into the challenges and decisions required of national and military leaders. These games represent the fusion of economic, political, diplomatic and military power. They illustrate how military power may complement, or lead, other elements of national power—or may even conduct actions that are, in essence, diplomatic or economic. Such insights help challenge the often-held tactical view that the military’s sole role is war.[87] Coupled with a challenging education program, these games broaden professional understanding of the ‘art of the possible’.[88] Broadening military thinking builds a greater understanding of theory and practice, thereby enhancing creative decision-making.

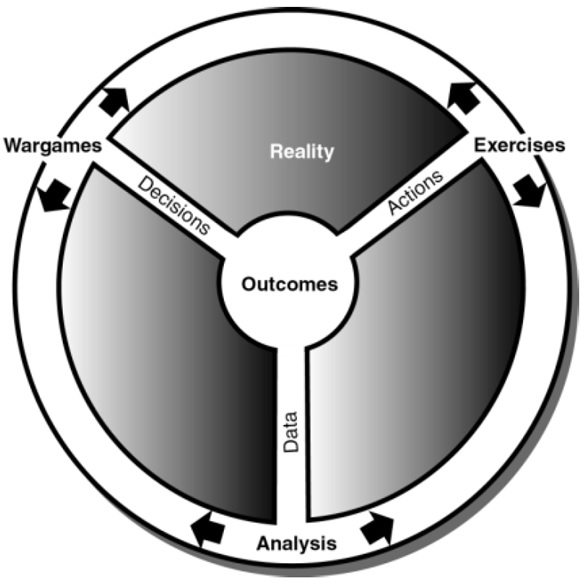

The above discussion highlights how immersive games, played deliberately and as free play, can help military professionals practise real-world decision-making. As Figure 5 illustrates, exercises provide practice for military professionals in how to undertake an action. Meanwhile, gaming provides experience in creative military decision-making.

Figure 5. A cycle of innovation and development that links gaming, analysis (education and/or simulation) and exercises[89]

These decision-making experiences can modify existing, or build new, mental models. Therefore, games can help increase the number of experiences available to a military professional’s heuristics and planning processes. It is these gaming-generated experiences that Nimitz directly cites as a key component of US victory in the Second World War. Currently the ADF relies almost exclusively on two episodic educational experiences to build strategic understanding: Staff Course and Higher Defence Course at the Australian War College.[90] Furthermore, the Australian Army relies heavily on TEWTs and course learning to build understanding of tactical (and, to a lesser degree, operational) theory. As Figure 5 indicates, such education (analysis) and exercises are important and should not be ignored. However, exercises like TEWTs are more akin to ‘Tactical Plans Without Troops’ than an experience to help change, build and grow the mental model library necessary for effective and creative decision-making.[91] Although research demonstrates the benefits of games, contemporary Western militaries still treat gaming as a curiosity.

Limiting Possible Military Thinking: Treating Gaming as a Fringe Activity

The last decade has seen a resurgence in civilian hobby gaming and Western military wargaming. Army’s Forces Command recently released a directive to increase wargaming within the Australian Army. The directive seeks to develop a wargaming network that leverages like-minded individuals to assist in possible unit activities.[92] Additionally, the directive establishes an inter-brigade wargame competition and sports-like club system. This is a laudable step forward. Yet its limitations are stark when compared to the interwar US military’s integration of unrestricted wargaming within education and training. Even ADF wargaming in the 1980s and early-1990s was more integrated than current practices.[93]

Except for a few notable institutions, most contemporary Western militaries have not formalised wargaming within their training and education systems.[94] Instead, such free-play unrestricted wargaming is often informal, characterised as an ‘insurgency’ or underground ‘fight-club’.[95] Such imagery may be evocative, but is also damning in its implication: that gaming is a fringe element within Western militaries. Focusing on gaming as a club-like activity rather than an integral part of the profession makes it less likely that ‘non-gamers’ will seek to engage in the pursuit. The risk is that gaming will continue to appeal to those already interested in gaming. Meanwhile, the wider military will continue to view gaming as a recreational hobby that provides niche professional outcomes, much like adventure training. Western militaries must learn from their history to gain a creative cognitive edge.[96] The military should actively and deliberately play games as a part of its formal training, education, and unit professional development.

Deliberate play differs from the traditional gameplay most people experience during family holidays while growing up. Casual gaming can assist in mental decision-making. Nevertheless, a casual association with games does not generate the same cognitive benefits when compared to an active interest in, and pursuit of, gaming.[97] Scholars indicate that the cognitive benefits of gaming are best seen in two different (sometimes overlapping) groups. The first is ‘hobby gamers’, or people who actively pursue and play games in their free time. These hobby games often meet all the requirements discussed above for an immersive and engaging environment. The second group are professionals who integrate gaming into a professional education system. A recent Australian Army Journal article entitled ‘Moulding War’s Thinking’ outlines how wargaming can be integrated into promotion courses.[98] Such an investment requires a cultural change in how the ADF views gaming—transitioning from a fringe activity to a professional norm. Like any cultural or habit-of-mind change, the development of a professional gaming culture needs to be built early in a military career.[99]

Building a Professional Gaming Culture: A Campaign of Gaming

To inoculate a professional and deliberate gaming culture within Army and the ADF, it is necessary to start early: ab-initio training. The US Marine Corps’ use of chess is a case study in successfully introducing gaming at recruit and initial employment training. Given how an officer’s life revolves around decision-making, the Royal Military College—Duntroon (RMC-D) also offers an opportunity for Army to develop professional gaming within the officer corps. Such a culture can be developed through a ‘crawl-walk-run’ construct similar to that seen in many training environments. Sebastian Bae, a RAND Corporation analyst, highlights the importance of such a staged approach.[100] Bae discusses how introducing highly immersive games too early often leads to failure. Such failure occurs because gaming, though growing in broader society, is not mainstream. Therefore, most staff cadets have little to no immersive gaming experience. Additionally, a significant cultural shock always occurs early in any ab-initio training (or an educational course such as those at the Australian War College). It is easy to deduce why, when limited experience and cultural shock combine, the sudden use of games can lead to negative views on gaming.[101] Such negative views are likely to bias future gaming experiences. Gaming should be slowly introduced to overcome this vicious cycle.

A ‘campaign of gaming’ approach at RMC-D seeks to introduce the benefits of immersive games to all Army officers.[102] As with any cultural change, building acceptance early makes it more likely that Army officers will continue to use games for professional development throughout their careers. The focus audience should be RMC-D second-class. These students have moved from their basic military training (third-class), and are now growing their tactical and wider military thinking. This campaign of gaming approach is similar to any other training subject that runs throughout second and first class. As such, the gaming ‘subject’ has four objectives. The first is to develop ‘game awareness’, or an appreciation for the utility of games as a learning tool. Next is developing an understanding of how to use games to assist conceptual learning (pedagogical experiences). Another objective is to explore opportunities to develop new mental models concerning military thinking. Finally, the subject seeks to enhance RMC-D’s broader critical thinking curriculum.

The approach introduces gaming slowly over the first few months of second-class. Then, when most students are comfortable with the idea of gaming as a part of the military profession, games are used for professional development and benefit. To reinforce the professional nature of such deliberate gaming, each game should end with a post-game discussion that considers the value of both the game and the decision experiences within it. This approach builds understanding of why games have utility and how they can be used to grow professional knowledge and experience. Underpinning this approach are the following activities:[103]

- Gaming and the Profession-of-Arms (Lesson). This lesson that outlines the links between decision-making, heuristics, and how games enhance decision-making. It helps explain why the military should professionally and deliberately play games.

- Gaming in the Military Profession—a Case Study (lesson). This lesson explores wargaming through a case study: US Navy and Army wargaming in the interwar period. The case study also looks at how wargaming helps develop successful military thinking prior to war in preparation for war.

- Gaming Types and Ideas (Practical/Syndicate [or two]). This is a syndicate discussion(s) that uses one or two simple games to explore game mechanics, and how such mechanics help mental skills. The syndicate could also explore the psychology of human interactions using a social deduction game.[D]

- How Games Model War (Practical/Syndicate [or two]). Using simple wargames, participants discuss how they model real-world military or political activity.[E]

- Incorporation of Games (several practicals/syndicates). Post developing game awareness, this activity uses some games to illustrate different theoretical models of competition or conflict. The historical games listed earlier may be relevant examples. Such syndicates should occur once or twice a month, over the second-class period, to build familiarisation and normalise gaming.

- Integrate Games into Tactical Thinking (several gaming opportunities). As advocated in ‘Moulding War’s Thinking’, tactical wargames should be played as a part of the first-class curriculum to complement and enhance TWETs and training.[104]

The first five activities help establish gaming as a norm within the profession of arms. These activities prepare staff cadets for the sixth activity: tactical wargaming to enhance mental models and creative decision-making. It is important to note that during the first five activities, games do not have to be played to completion. Playing a few rounds of a game will help students understand and realise the value of games. Professionally, what matters from a mental model and learning perspective is the post-game discussion. Furthermore, as the US Marine experience with chess highlights, if staff cadets wish to continue games in their free time, such a professional pastime should be encouraged (probably with directing staff role models). This approach can be adapted to support other military education courses and inculcate a joint professional gaming culture. For example, the approach could be included in the Australian Defence Force Academy (ADFA) military training component, possibly in the second and third years. The approach could be adapted to Australia’s Staff Course and Higher Defence Course to help facilitate new mental models concerning strategic and operational thinking.[105] It is true that there are risks with this approach. One obvious risk is that current instructors have little or no exposure to gaming and its benefits. However, these risks can be overcome if Army leverages existing ‘gaming enthusiasts’ while gaming normalises within the wider officer corps. Furthermore, this approach would be enhanced by using a new professional wargaming system developed by the Australian Army: Barrier to Entry.[106]

Barrier to Entry straddles the strategic and operational levels of war in a similar fashion to the wargames of the interwar US military. Army currently uses the system to validate warfighting concepts. Yet it has the potential to be so much more. As a facilitated gaming system, Barrier to Entry captures the complexity of war and illustrates the importance of prewar and in-war actions. In this regard, Barrier to Entry lifts officer thinking out of the tactical, reinforcing the importance of broader military, economic and political theory to frame the problems of war. As a ‘homegrown’ professional gaming system, it may help instil an Australian middle power context within the thinking of ADF officers.[107] At RMC-D (and ADFA), the game could be used to introduce such strategic and operational concepts to staff cadets after tactical wargaming. Such gaming allows cadets to explore strategic thinking and helps put their recent tactical learning within a wider context. However, Barrier to Entry should be used sparingly at RMC-D to not detract from junior officer tactical development. Barrier to Entry’s real impact is at the Australian War College. Here, the system directly complements operational and strategic education. Much like wargames in the US interwar period, Barrier to Entry, played during the final months of the Staff Course, can help students explore the expansive nature of military theory. Such opportunities help enhance military thinking.

Conclusion

This article outlines the military benefits of deliberate gaming. Deliberate gaming is where people actively choose to play and practise games. A key element of deliberate gaming within a professional context is the acceptance of, and willingness to use, games. The article explains the research that demonstrates how deliberately playing games helps increase the mental skills necessary for successful decision-making. This research also demonstrates how deliberately playing immersive games helps grow new mental models within military professionals. Several factors make games immersive. First, immersive games facilitate real-time player interactions. Next, these games provide a useful representation of the key elements of real-world decision-making. Immersive games also have an engaging theme. Many modern ‘hobby games’ meet these requirements, are readily available, and do not need external facilitators. The mental models developed through these immersive experiences directly influence and enhance military thinking, planning and creative decision-making. Nevertheless, contemporary Western militaries rarely incorporate gaming into training and education. Instead, many Western militaries, including the ADF, treat gaming as a fringe element—a curiosity more akin to a hobby rather than a serious military activity. Contemporary practice is in stark contrast to Western military history. Historically, Western militaries integrated gaming into education and training, and treated gaming as a professional pastime. To achieve the benefits of gaming, the article argues, Army, and the ADF more generally, need to re-establish a culture of professional gaming.

To change current culture, the article posits, gaming should be a part of RMC-D. Introducing games early in a military career helps grow a willingness to use games in a professional setting. Within RMC-D, gaming should be included as part of the second-class curriculum. The article presents a range of activities that would help grow staff cadet understanding of gaming and its military benefits. This approach would culminate in first-class with tactical wargames that build officer decision-making and tactical brilliance. The approach advocated within this article could be adapted to ADFA and the educational courses at the Australian War College: Staff Course and Higher Defence Course. Such adaptation would help build a joint culture and enable mid-ranking officers to develop a greater appreciation of operational and strategic thinking.

Gaming provides a means to cheaply and repeatedly provide immersive decision-making experiences that help grow mental models and develop strong habits of mind within military professionals. A wide array of mental models also enhances the potential for creative military decision-making. Future conflicts are likely to see the ADF lose the technological, material and mass advantages it held during the operations of the last four decades. Enhancing Army and ADF habits of mind and decision-making may be the intellectual edge needed during this time of strategic uncertainty and great power competition.

About the Author

Colonel Nick Bosio CSC has held a range of command and staff appointments across tactical, campaign and strategic posts, both within Australia and on operations. His experiences include roles as Chief of Campaign Plans for a 3-Star Coalition Headquarters, and Commanding Officer of the 6th Engineer Support Regiment. Colonel Bosio holds a Bachelor of Engineering and three Masters Degrees. He has been awarded a research doctorate focusing on military theory, military studies, and systems thinking. He is currently the Director of Military Strategic Plans.

[A] A rotating filing device often used to store business contacts.

[B] A TEWT is a map-based exercise where a military professional seeks to solve a tactical problem. The outcome of a TEWT is often a concept of operations (simplified military plan), and a series of map-based graphics that represent the different phases (stages) of the plan. TEWTs are static, in that they present a plan and do not ‘play out’ the post H-hour actions of the plan. A TEWT is often done at the physical location of the tactical problem to help develop an appreciation of terrain.

[C] A staff cadet is the name given to a RMC-D officer candidate under ab-initio training.

[D] Some illustrative games for pattern matching may include chess or Star Realms (simple deck-builder card game). The psychology of human interactions is best seen in social deduction games like Resistance or Secret Hitler.

[E] Some illustrative games for this may include 13 Days, which simulates the 13 days of the Cuban Missile Crisis; Blitzkrieg, a very simple strategic wargame that represents the Second World War at the highest level; Air, Sea, Land, which is a simplified operational wargame using cards. There are also science fiction and fantasy equivalents.

Endnotes

[1] Williamson Murray, 2014, ‘US Naval Strategy and Japan’, in Williamson Murray and Richard Hart Sinnreich (eds), Successful Strategies: Triumphing in War and Peace from Antiquity to the Present (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press), 10.39–10.40.

[2] Azar Gat, 2001, A History of Military Thought: From the Enlightenment to the Cold War, 1st edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 256.

[3] This is detailed in several official and academic documents. For clarity, two sources are presented to provide examples of the analysis: John C Blaxland, 2019, A Geostrategic SWOT Analysis for Australia, The Centre of Gravity Series (Canberra: Australian National University); Department of Defence, 2020, 2020 Defence Strategic Update (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia), 11–17.

[4] A range of commentators, both within Australia and internationally, advocate for changes to Western military and ADF capabilities. Many of these commentators assert that new technologies mean forces must change. This is similar to the arguments made by revolution in military affairs (RMA) advocates. For discussion and summary, see Nicholas J Bosio, 2022, ‘An Analysis of the Relationship between Contemporary Western Military Theory, Systems Thinking, and their Key Schools-of-Thought’, PhD thesis, Australian National University, 128–133, at: http://hdl.handle.net/1885/260048. In many cases, such technologically driven strategic advice lacks historical, changing geostrategic or military theory context. During the writing of this article, Greg Sheridan published a series of articles in The Australian that are good illustrative examples of such Australian commentary. See Greg Sheridan, ‘Nation Must Beef Up Military or Pass Molotov Cocktails’, The Australian, 4 March 2022, at: https://www.theaustralian.com.au/inquirer/a-wakeup-call-for-the-west-we…; Greg Sheridan, ‘Defence Policy on the Never-Never’, The Australian, 8 March 2022, at: https://www.theaustralian.com.au/world/defence-policy-on-the-nevernever…; Greg Sheridan, ‘Albanese is Right to Target PM on Defence Failures’, The Australian, 9 March 2022, at: https://www.theaustralian.com.au/world/defence-policy-on-the-nevernever….

[5] Throughout the interwar period, a range of commentators and theorists advocated for technological solutions to the problems of war. Examples of well-known theorists and commentators still studied in today’s staff colleges include Douhet and Mitchell (air power advocates), Fuller and Liddell Hart (mechanised and air power advocates), and Tukhachevsky (air power and mechanised advocate). Such theorists, much like RMA theorists, often focused solely on tactical advantage, decisive battle, and an over-reliance on a specific technological solution that would provide rapid success—either within a single domain, or across multiple domains. For discussion of theorists and their technological and decisive battle emphasis, see Andrew Latham, 2002, ‘Warfare Transformed: A Braudelian Perspective on the "Revolution in Military Affairs"’, European Journal of International Relations 8, no. 2: 232–234; Theo Farrell and Terry Terriff (eds), 2002, The Sources of Military Change: Culture, Politics, Technology (London: Lynne Rienner Publishers), 12–16; HP Willmott and Michael B Barrett, 2010, Clausewitz Reconsidered (Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger Security International), 108–110, 73; Thomas Hippler, 2013, Bombing the People—Giulio Douhet and the Foundations of Air-Power Strategy, 1884–1939 (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press), 250–253; Jan Angstrom and JJ Widen, 2015, Contemporary Military Theory: The Dynamics of War (New York, NY: Routledge), 98–101, 65–66, 66 (Table 9.1); Cathal J Nolan, 2017, The Allure of Battle: A History of How Wars Have Been Won and Lost (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 578–582.

[6] French’s analysis is detailed in his work Raising Churchill’s Army. The issues of poor British doctrine and thinking, and their effect on operations against the Germans, are seen clearly in his analysis of the early periods of the North African campaign (1940–1941). David French, 2000, Raising Churchill’s Army: The British Army and the War against Germany, 1919–1945 (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 215–224.

[7] Ibid., 21.

[8] PJ McCarry, 1991, This Is Not a Game: Wargaming for the Royal Australian Air Force (Canberra: Air Power Studies Centre), 1–4; Williamson Murray, 2011, War, Strategy, and Military Effectiveness, Kobo eBook edition (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press), 7.15; Matthew B Caffrey Jr, 2019, On Wargaming: How Wargames Have Shaped History and How They May Shape the Future, The Newport Papers, vol. 43 (Newport, RI: United States Naval War College), 46.

[9] Caffrey also outlines how Hitler directed the German military to not undertake any strategic wargames on possible political and economic responses by other nations. Caffrey, 2019, 43, 46.

[10] Hopkins’s analysis of the postwar commissions and reports also reinforces this. Several scholars cite the US military’s interwar period cultural, educational and capability development as critical to their success in the Second World War. See Edward S Miller, 2007 (1991), War Plan Orange: The U.S. Strategy to Defeat Japan, 1897–1945 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press), 323–330; Eliot A Cohen, 1994, ‘The Strategy of Innocence? The United States, 1920–1945’, in Williamson Murray, MacGregor Knox and Alvin Bernstein (eds), The Making of Strategy: Rulers, States, and War (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press), 461–464; William B Hopkins, 2008, The Pacific War: The Strategy, Politics, and Players that Won the War (Minneapolis, MN: Zenith Press), 19–27, 342–344; MacGregor Knox and Williamson Murray (eds), 2001, The Dynamics of Military Revolution 1300–2050, 12th Kobo eBook edition (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press), 10.8; Williamson Murray and Allan R Millett, 2001, A War to Be Won: Fighting the Second World War, Kindle edition (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press), 8020–8032 (Appendix 2); Williamson Murray, 2011, Military Adaptation in War: With Fear of Change, Kobo eBook edition (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press), 2.31; Murray, 2011, War, Strategy, and Military Effectiveness, 7.13–15; Murray, 2014, ‘US Naval Strategy and Japan’, 10.2–3, 10.12–13.

[11] Sean M Judge, 2018, The Turn of the Tide in the Pacific War: Strategic Initiative, Intelligence, and Command, 1941–1943, eBook edition (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas), 209–210.

[12] See previous endnote for scholars. This point is also reinforced by Nimitz. See Donald C Winter, 2006, ‘Remarks by Secretary of Navy,’ remarks presented at the Naval War College's 2006 Current Strategy Forum, Newport, Rhode Island, USA, 13 June; Murray, 2014, ‘US Naval Strategy and Japan’, 10.39.

[13] These dispositions underpin the definition of pluralist habit of mind. See Patrick Sullivan, 2014, A New Writing Classroom: Listening, Motivation, and Habits of Mind, ePub edition (Logan, UT: Utah State University Press), 152–153; Arthur L Costa and Bena Kallick, 2018, ‘Habits of Mind: Strategies for Disciplined Choice Making’, The Systems Thinker, at: https://thesystemsthinker.com/habits-of-mind-strategies-for-disciplined…; Nicholas J Bosio, 2020, ‘Moulding War's Thinking: Using Wargaming to Broaden Military Minds’, Australian Army Journal XVI, no. 2: 35–38.

[14] Bosio summarises the research and discussion of habits of mind across multiple disciplines, including the works of Cohen, Gole, Mansoor and Murray (all cited later) on military habits of mind. A pluralist habit of mind is defined as having or using thinking dispositions that accept pluralism, are willing to consider alternative views, and can accept and integrate a wide range of schools of thought and worldviews. Pluralism is a key part of military theory, and is defined as the use of different paradigms or schools of thought, and their related theories and methodologies, to consider problems within a field of study, in this case military theory. Bosio, 2022, ‘Relationship between Contemporary Western Military Theory, Systems Thinking’, 56, 58–60, 223–227, 64–67.

[15] The research and scholarly work relating to this is summarised by Bosio. Carse takes the concept of mental development through shared game experience further by placing it within a metaphysical context. See Bosio, 2020, 37–38; James P Carse, 1986, Finite and Infinite Games (New York, NY: The Free Press); John Lillard, 2016, Playing War: Wargaming and U.S. Navy Preparations for World War II (Lincoln, NE: Potomac Books), 137.

[16] Anon., 1898, ‘Foreign War Games’, in Selected Professional Papers Translated from European Military Publications (Washington, DC: Government Publishing Office), 249.

[17] Jim Storr, 2009, The Human Face of War (London: Continuum), 145–155. McLucas succinctly summarises the research in his first chapter. Although Storr refers to this mental decision-making as ‘intuition’, he places the concept of heuristics within the military context. Storr also references Klein. See Alan C McLucas, 2003, Decision Making: Risk Management, Systems Thinking and Situation Awareness (Canberra: Argos Press), 16–31.

[18] Storr refers to these mental tools as intuition. Klein’s work goes further, highlighting that intuition is derived from heuristic decision-making built on significant repetition of action and a large ‘library’ of mental models. See Storr, 2009, 148–149; Gary Klein, 1998, Sources of Power: How People Make Decisions (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), 35–44.

[19] Gigerenzer et al. provide extensive research into the use of heuristics in the book Simple Heuristics That Make Us Smart. This research is further supported by Klein’s Sources of Power. Although Kahneman highlights concerns with heuristics and ‘natural decision-making’ (in Thinking Fast and Slow), even Kahneman’s work reinforces the basic premise and preference for heuristics within decision-making. Specifics on heuristics and cognitive load are provided by Martignon and Laskey. For summary, see Laura Martignon and Kathryn B Laskey, 1999, ‘Bayesian Benchmarks for Fast and Frugal Heuristics’, in Gerd Gigerenzer, Peter M Todd and ABC Research Group (eds), Simple Heuristics That Make Us Smart (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 183, 86–87; Daniel Kahneman and Gary Klein, 2009, ‘Conditions for Intuitive Expertise: A Failure to Disagree’, American Psychologist 64, no. 6: 524–225.

[20] Cited in McLucas, 2003, 18–19.

[21] Gigerenzer and Todd summarise the research in the first chapter of Simple Heuristics That Make Us Smart. See Gerd Gigerenzer and Peter M Todd, 1999, ‘Fast and Frugal Heuristics: The Adaptive Toolbox’, in Gerd Gigerenzer, Peter M Todd and ABC Research Group (eds), Simple Heuristics That Make Us Smart (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 14–15.

[22] Klein, 1998, 31–74 (chapters 4 and 5); Gigerenzer and Todd, 1999, 16–17; McLucas, 2003, 22.

[23] This figure illustrates the summary of the heuristic process, as outlined by Gigerenzer and Todd and by Klein. See Gigerenzer and Todd, 1999, 18; Klein, 1998, 24–28.

[24] These two steps are extensively covered in chapters 4 and 5 of Klein’s Sources of Power, and Parts I and II of Simple Heuristics That Make Us Smart. Klein and Gigerenzer et al. summarise these requirements in their third and first chapters, respectively. See Klein, 1998, 15–30 (Chapter 3); Gigerenzer and Todd, 1999, 16.

[25] The definition (and quotation) is from Senge. Though Storr does not refer to mental models, he recognises their importance in military decision-making with his discussion of ‘fairly high-level precis or abstraction of the situation’. See Peter M Senge, 1990, The Fifth Discipline, Kobo ePub edition (London: Random House Business Books), 8; Storr, 2009, 146, 55.

[26] Although many make this point, Storr’s discussion on Rommel, Patton and other successful military commanders highlights the importance of pedagogical experience in mental model development. See Storr, 2009, 155.

[27] This relates to the two types of knowledge: procedural and propositional knowledge. Procedural knowledge is knowledge of how and why. Propositional knowledge is knowledge of what and why. For a succinct summary, see Mick B Ryan, 2016, The Ryan Review: A Study of Army’s Education, Training and Doctrine Needs for the Future (Canberra: Department of Defence), 48–49; Nicholas J Bosio, 2018, Understanding War's Theory: What Military Theory Is, Where It Fits, and Who Influences It?, Australian Army Occasional Paper—Conflict Theory and Strategy No. 001 (Canberra: Australian Army Research Centre), 11–14.

[28] The following summarise and succinctly explain these links: Paul Davidson Reynolds, 1976, A Primer in Theory Construction (Indianapolis, IN: The Bobbs-Merrill Company), 21–43; Klein, 1998, 152–153, 261–69; Bosio, 2018, 11–14.

[29] Klein, 1998, 24–28.

[30] Creativity in this case relates to a wide range of mental models that give different options to the heuristic. The need for broad mental models is outlined by both Klein and Storr. See Klein, 1998, 32–35; Storr, 2009, 143–153, 55.

[31] See George A Miller, 1956, ‘The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on Our Capacity for Processing Information’, The Psychological Review 63, no. 2; Alan Baddeley, 1994, ‘The Magical Number Seven: Still Magic After All These Years?’ Psychological Review 101, no. 2: 356.

[32] This tool is known as the ‘availability heuristic’, which is often used as a ‘sub-heuristic’ within decision-making situations. See Stephen J Hoch, 1984, ‘Availability and Interference in Predictive Judgment’, Journal of Experimental Psychology 10, no. 4: 658–660; Scott Plous, 1993, The Psychology of Judgment and Decision Making (New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education), 121 (Chapter 11); Ralph Hertwig, Ulrich Hoffrage and Laura Martignon, 1999, ‘Quick Estimation: Letting the Environment Do the Work’, in Gerd Gigerenzer, Peter M Todd and ABC Research Group (eds), Simple Heuristics That Make Us Smart (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 213–218.

[33] Klein explains these as ‘typical and familiar’ problems compared to ‘complex’ problems. Klein highlights the cognitive process, and by extension loading, of the two situations. See Klein, 1998, 24–28, 27 (Figure 3.2).

[34] This was a key deduction in Klein’s work, and is reinforced by the joint analysis of Kahneman and Klein. Storr’s discussion of military decision-making makes the same point. See Klein, 1998, 105–107; Kahneman and Klein, 2009, 515–517, 22–23; Storr, 2009, 147–148, 55.

[35] Australian Defence Force, 2022, ADF-P-5—Planning (Canberra: Department of Defence), 10–12.

[36] These statements summarise the discussion in ibid., 10–12, 56, 69–72, 77–78.

[37] Ibid., 12.

[38] Research into this is summarised by Peter B Checkland and Jim Scholes, 1990, Soft Systems Methodology in Action (Chichester, London: John Wiley and Sons), A9-A11; William Ives, Ben Torrey and Cindy Gordon, 2002, ‘Knowledge Sharing Is a Human Behaviour’, in Daryl Morey, Mark Maybury and Bhavani Thuraisingham (eds), Knowledge Management: Classic Contemporary Works (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press), 121–124; McLucas, 2003, 14–16.

[39] The theory of how mental models and knowledge transitions between people through the process of making mental models explicit, updated and then internalised is summarised by Takeuchi and Nonaka. Bosio also summarises the research within a military wargaming context. See Hirotaka Takeuchi and Ikujiro Nonaka, 2002, ‘Classic Work: Theory of Organizational Knowledge Creation’, in Daryl Morey, Mark Maybury and Bhavani Thuraisingham (eds), Knowledge Management: Classic Contemporary Works (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press), 139–158; Bosio, 2020, 37–38.

[40] Hope H Seck, ‘Why These Infantry Marines Have a New Obsession with Chess’, Military.com, 4 May 2021, at: https://www.military.com/daily-news/2021/05/04/why-these-infantry-marin…;

[41] Ibid.

[42] Some websites provide useful summaries of the benefits (e.g. healthline, at: https://www.healthline.com/health/benefits-of-playing-chess#takeaway; and The Science Times, at https://www.sciencetimes.com/articles/27306/20200915/10-things-playing-chess-brain.htm). For a summary of the academic literature, see William M Bart, 2014, ‘On the Effect of Chess Training on Scholastic Achievement’, Frontiers in Psychology 5.

[43] Grabner et al. summarise the research that indicates how playing chess casually may assist. However, the cognitive benefits are limited compared to deliberate playing and practising of chess. See Roland H Grabner, Elsbeth Stern and Aljoscha C Neubauer, 2007, ‘Individual Differences in Chess Expertise: A Psychometric Investigation’, Acta Psychologica 125, no. 3: 401–402.

[44] Ramon Aciego, Lorena Garcia and Moises Betancort, 2012, ‘The Benefits of Chess for the Intellectual and Social-Emotional Enrichment in Schoolchildren’, The Spanish Journal of Psychology 15, no. 2: 558; Fariba Fattahi et al., 2015, ‘Auditory Memory Function in Expert Chess Players’, Medical Journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran 29: 5–6.

[45] Fattahi et al. acknowledge the overall increase in mental capacity due to deliberate playing of chess. They also highlight the link between short, immediate and longer-term memory recall, ‘buffer’ capacity, and speed of cognition. See Fattahi et al., 2015, 5–7.

[46] These two days are indicative. The author’s local game store has a standing evening event for Flesh and Blood and Magic on these days, respectively.

[47] The process of analysis and decision-making outlined here has been traced in a range of games and actions. Klein uses a similar process to build military decision-making capacity in US Marine squad leaders. Ballesteros et al. apply a similar processing form through a computer game system to build cognitive development within older adults. For summary and discussion, see Klein, 1998, 99–107; Mark Newman, ‘Developing Life Skills Through Play’, Business Wire, 17 December 2004, at: https://www.proquest.com/wire-feeds/developing-life-skills-through-play…; Beth Casper, ‘Cognitive Calisthenics’, Statesman Journal, 3 January 2005, at: https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/cognitivecalisthenics/docview/44003…; Soledad Ballesteros et al., 2015, ‘A Randomized Controlled Trial of Brain Training with Non-Action Video Games in Older Adults: Results of the 3-Month Follow-Up’, Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 7: 7–10.

[48] Klein notes this preference in decision-making. The previously cited McLucas summary also outlines the cognitive research in this area. See Klein, 1998, 99–100.

[49] See previous discussion under ‘Understanding Decision-Making: The Heuristic’.

[50] Scholars have identified the potential bias that is often contained within Western military exercises and simulations. The works of Murray and Cohen are notable in this area. Bosio summarises these concerns in relation to the lead-up to the Iraq War, which has several similarities to contemporary exercise focus and design. See Murray, 2011, Military Adaptation in War; Murray, 2011, War, Strategy, and Military Effectiveness; Eliot A Cohen and John Gooch, 2006, Military Misfortunes: The Anatomy of Failure in War (New York, NY: Free Press); Bosio, 2022, ‘Relationship between Contemporary Western Military Theory, Systems Thinking’, 231–367 (Chapter 8).

[51] Scholarship on chess, discussed earlier, highlights these links. Kahneman and Klein highlight similar cognitive development with respect to intuitive judgement. See Kahneman and Klein, 2009, 520–521.

[52] It is noted that competitive games can also generate a similar feel through ‘trash talk’, where one player attempts to psychologically undermine the opponent.

[53] The immersive nature of gaming, and how it assists in learning, is explored in wider literature, which often views a game as ‘a voluntary activity, separate from the real life, creating an imaginary or immersive world’. See Sara I de Freitas, 2006, ‘Using Games and Simulations for Supporting Learning’, Learning, Media and Technology 31, no. 4: 344; Lillard, 2016, 137.

[54] Although this is explained by Klein and by Gigerenzer et al., Storr’s analysis links the need for a library of mental models to the military context. See Storr, 2009, 148–149, 55–56.

[55] Reportedly stated in a private letter to the President of the Naval War College after the Second World War. Cited by Secretary of Navy, Donald Winter. See Winter, 2006, 1.

[56] Cohen, 1994, 441–442, 62–63; Henry G Gole, 2003, The Road to Rainbow: Army Planning for Global War, 1934–1940 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press), 141–149; Peter R Mansoor, 2014, ‘US Grand Strategy in the Second World War’, in Williamson Murray and Richard Hart Sinnreich (eds), Successful Strategies: Triumphing in War and Peace from Antiquity to the Present (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press), 11.2–6.

[57] Cohen, 1994, 462; Gole, 2003, 154–156; Mansoor, 2014, 11.4–6, 11.16, 11.46–47.

[58] Ján Spišák, 2013, ‘Military Concepts—A Background for Future Capabilities Development’, Economics and Management, no. 1: 75–76; Christopher R Smith, 2018, ‘On Future Thinking and Innovation: How Military Concept Writing Can Unwittingly Suppress Innovation’, Australian Army Journal XIV, no. 1: 123–124; Bosio, 2022, ‘Relationship between Contemporary Western Military Theory, Systems Thinking’, 133, 299.

[59] Miller discusses how War Plan Orange and its wargaming became an analogy that influenced thinking and supported real-time Second World War planning. Both Gole and Mansoor highlight how the Rainbow Plans informed both US grand strategy and coalition thinking. Bosio indicates how wargames helped influence US military thinking over the interwar period. See Edward S Miller, 2007, 337–345; Gole, 2003, 141–149; Hopkins, 2008, 27; Mansoor, 2014, 11.46–47; Bosio, 2020, 36–38.

[60] There is significant research in this area, covering education, leadership, business and psychology. Kahneman, Klein, and Gigerenzer et al. identify these issues. McLucas also provides a succinct summary of both cognitive science and psychological research. For a summary of the research into mental model changes through gaming and scenario planning, see Margaret B Glick et al., 2012, ‘Effects of Scenario Planning on Participant Mental Models’, European Journal of Training and Development 36, no. 5: 488–491.

[61] See Endnote 27.

[62] Murray’s analysis of military education from the interwar period to the 1990s reinforces this point. Murray’s points are echoed by other scholars, including Mansoor, Storr and Davidson. Cimbala and Willmott and Barrett imply it in their analysis. The works of these war studies scholars highlight that training provides procedural knowledge, while challenging education reinforces military propositional knowledge. The Australian Army’s Ryan Review also references the relevant research. See Murray, 2011, War, Strategy, and Military Effectiveness, 3.10–12; Mansoor, 2014, 11.48; Storr, 2009, 155–156; Janine Davidson, 2010, Lifting the Fog of Peace: How Americans Learned to Fight Modern War (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press), 198–199; Stephen J Cimbala, 2001, Clausewitz and Chaos: Friction in War and Military Policy (Westport, CT: Praeger), 198–199; Willmott and Barrett, 2010, 163–76; Ryan, 2016, 25 (Fn 32), 33–34.

[63] See Endnote 27.

[64] In a contemporary military context, this relates to Felker’s conclusion. Caffrey explains the utility of wargaming in a military context. This is similar to wider research that indicates how human interaction in games can modify mental models through exploratory learning, or ‘a mode of learning whereby learning takes place through exploring environments, lived and real experiences, with tutorial or peer support’ (de Freitas, 2006, 344). For a summary of current analysis of analogue and digital games for learning development, see Katie Salen (ed.), 2008, The Ecology of Games: Connecting Youth, Games, and Learning (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press). See also Craig Felker, 2007, Testing American Sea Power: U.S. Navy Strategic Exercises, 1923–1940, ePub edition, vol. 107 (College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press), 137; Caffrey, 2019, 43, 277–289; Glick et al., 2012; Vicki Phillips and Zoran Popović, 2012, ‘More than Child's Play: Games Have Potential Learning and Assessment Tools’, The Phi Delta Kappan 94, no. 2: 27–30.

[65] Bosio summarises this point. The statement is also derived from the gaming literature as outlined by Caffrey and by de Freitas. McCreight also outlines the key elements that relate to games as a useful representation. See Bosio, 2020, 28–29; Caffrey, 2019, 43, 261–264; de Freitas, 2006, 344; R McCreight, 2012, ‘Scenario Development: Using Geopolitical Wargames and Strategic Simulations’, Environment Systems and Decisions 33, no. 1: 30.

[66] See Endnote 64 for research areas. Wheaton and Brown make a similar point by describing how games can be used to form conceptual metaphors that help explain complex strategic problems. See Kristan J Wheaton and Jason C Brown, ‘The Games We Play: Understanding Strategic Culture through Games’, Modern War Institute website, 23 March 2022, at: https://mwi.usma.edu/the-games-we-play-understanding-strategic-culture-….

[67] Nineteenth century military research discusses this. Caffrey, McGrady, Fielder and other scholars summarise the modern research in this area. See Anon., 1898, 261–265; Caffrey, 2019, 43, 11–17; Ed McGrady, ‘Getting the Story Right about Wargaming’, War on the Rocks, 8 November 2019, at: https://warontherocks.com/2019/11/getting-the-story-right-about-wargami…; James Fielder, ‘Reflections on Teaching Wargame Design’, War on the Rocks, 1 January2020, at: https://warontherocks.com/2020/01/reflections-on-teaching-wargame-desig…; Soenke Marahrens, ‘Assessing the Impact of a Kriegsspiel 2.0 in Modern Leadership and Command Training’, Divergent Options, 17 May 2021, at: https://divergentoptions.org/2021/05/17/assessing-the-impact-of-a-krieg….

[68] Research into solitaire games remains limited. However, video game research into single-person games suggests that they help produce procedural knowledge, but not necessarily propositional knowledge. Research into strategic solitaire games (e.g. Dune Imperium, one-player Pandemic) has not occurred at the time of writing.

[69] This is based on the definition of a model and simulation game. See McCreight, 2012, 30; Caffrey, 2019, 43, 262–264; Bosio, 2020, 28–29.

[70] How Diplomacy may assist politicians and diplomats is described in Haoran Un, ‘Diplomacy: The Most Evil Board Game Ever Made’, Lifehacker AU, 10 November 2017, at: https://www.lifehacker.com.au/2017/11/diplomacy-the-most-evil-board-gam…; David Klion, ‘The Game that Ruins Friendships and Shapes Careers’, Foreign Policy, 23 October 2020, at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/10/23/the-game-that-ruins-friendships-an…

[71] A theory of mind is the capacity for one person to determine what another may be thinking based on their own experiences and understanding. Broadening experiences helps broaden one’s theory of mind.

[72] Bosio summarises the research into free-play and outlines the difference between an ‘optimisation’ wargame as used in Course of Action Analysis, and an unrestricted wargame. See Bosio, 2020, 29–30, 33, 35–36.

[73] Bosio, 2018, 35–37; Bosio, 2022, ‘Relationship between Contemporary Western Military Theory, Systems Thinking’, 33–39.

[74] The level of extent of US military wargames is discussed by Bosio (2020), Cohen (1994), Gole (2003), Mansoor (2014) and Murray (2011, 2014).

[75] Lillard’s extensive research, already cited, outlines the games at all levels and their broad mechanics.

[76] Some illustrative examples are seen in McCreight, 2012; Rex Brynen, ‘Review: Matrix Games for Modern Wargaming’, PAXsims, 20 September 2014, at: https://paxsims.wordpress.com/2014/09/20/review-matrix-games-for-modern…; Defence Science and Technology Laboratory, 2021, ‘Dstl Wargames the Power of Influence’, UK Government, accessed 18 March 2022, at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/dstl-wargames-the-power-of-influence…;

[77] Images from various sources. Left: Caffrey, 2019, 43; top right: Brynen, 2014; bottom right: Defence Science and Technology Laboratory, 2021.

[78] Both Lillard and Felker, previously cited, provide explanations of war gaming that today would be classed as ‘operational wargaming’.

[79] James Lacey, ‘How Does the Next Great Power Conflict Play Out? Lessons from a Wargame’, War on the Rocks, 22 April 2019, at: https://warontherocks.com/2019/04/how-does-the-next-great-power-conflic…; McGrady, 2019; Mitch Reed, ‘The Operational Wargame Series: The Best Game Not in Stores Now’, No Dice No Glory, 23 June 2021, at: https://nodicenoglory.com/2021/06/23/the-operational-wargame-series-the…

[80] Both Lillard and Felker, previously cited, provide explanations on war gaming that today would be classed as ‘tactical wargaming’.

[81] McGrady, 2019; Marahrens, 2021; Paul Kearney and Sebastian J Bae, ‘Use Wargaming to Sharpen the Tactical Edge’, War Room—US Army War College, 8 March 2021, at: https://warroom.armywarcollege.edu/wargaming-room/tactical-edge/amp/?fb…

[82] Images from various sources. Top left: US Naval War College, 2016, US Naval War College Academic Catalog (Newport, RI: US Navy), 2; bottom left: Jeff McAleer, ‘Abandon Ship! A Review of Fletcher Pratt's Naval Wargame: War gaming with Model Ships 1900–1945’, The Gaming Gang, 7 January 2012, at: https://thegaminggang.com/our_reviews/abandon-ship-a-review-of-fletcher…; top right: Reed, 2021; bottom right: Lacey, 2019.

[83] Bosio, 2018, 19–27.

[84] The need to broaden career management at a more junior officer level is outlined in Nicholas J Bosio, ‘Integrated Campaigning (Part 2): Developing Our People for Integrated Campaigning’, The Cove, 4 April 2022, at: https://cove.army.gov.au/article/integrated-campaigning-part-2-developi…

[85] The author thanks Darren Huxley and David Goyne for the game suggestions and summaries.