Introduction

Change is a constant in war. But the chaos of constant change can be minimised by the act of planning. Doctrine advises that, to be effective, planning must facilitate movement through the adaptation cycle more quickly than the enemy.[1]This proposition is often mistaken for implying that success in war demands only quick adaptation. This conclusion is a misconception that tends to unnecessarily constrain military thinking. Success in war is dependent on the achievement of superior adaptation. Thus, adaptation in the context of battle against an adversary is relative. One side’s adaptive cycle is considered superior when the opponent’s is relatively slower. It follows, then, that while increasing the speed of adaptation is useful, commanders may also achieve superior adaptation by simply slowing down the speed of the enemy’s.

This paper explores the concept of adaptation and the role of military planning in its achievement. The analysis does not refute that current doctrine allows for planning measures that have the purpose of slowing an enemy’s capacity to adapt; nor does it seek to replace the nesting of task and purpose across battlespace operating systems. Indeed, much of the conceptual framework discussed in this paper will be self-evident to many experienced commanders. Rather, it deliberately links many of these concepts to provide commanders with an additional tactical manoeuvre tool to aid the proactive slowing of an enemy’s capacity to react in battle. First, it outlines the criticality of adaptation in war, identifies the link between adaptation and manoeuvre warfare, and summarises current planning measures that slow an enemy’s adaptation. The paper then demonstrates the shortcomings of the contingency plan as a reactive method to respond to change, before contrasting it with the Emergent Decisive Event (EDE), a proactive method to more deliberately bring about a superior adaptive cycle. To illustrate the relevance of the EDE, the paper concludes with a short case study of Pearl Harbor and the effective employment of the EDE by the Imperial Japanese ‘Carrier Striking Task Force’.

Adaptation, Manoeuvre Warfare, and Superiority

Adaptation in battle is essential as it is the method by which a force can effectively respond to wide-ranging threats.[2] Throughout history, the force that adapts better to changing conditions is usually the force that prevails over its adversary. Historical examples are plentiful: Mehmed demonstrated the potency of adaptive warfare when he moved his fleet overland to bypass Byzantium harbour defences during the siege of Constantinople;[3] Napoleon did so with his counterattack on a weakened Allied centre at the Battle of Austerlitz;[4] and the combined French and British forces achieved superior adaptation over the Germans with their rally and counter during the first battle of the Marne.[5] The US Joint Special Operations Task Force relearned the relevance of adaptation in 2004 against a less trained, ill-equipped but interconnected al-Qaeda, challenging the US commanders to rethink their structures, planning and processes in order to achieve decision superiority.

Adaptation is also inherent in manoeuvre warfare. The commander’s attempt to create a ‘turbulent and rapidly deteriorating situation’ for the enemy is dependent on the ability to ‘change physical and non-physical circumstances more rapidly than the enemy can adapt’.[6] A survey of manoeuvre warfare’s tenets provides further evidence that they are connected to the concept of relative adaptation superiority:

- Combined arms teams. This tenet provides the commander with the capacity to balance the vulnerability of components of the force against the strengths of the enemy’s.[7] Such versatility poses a dilemma for an enemy commander by slowing decision-making and adaptation, as to target a weakness of one part of the friendly force’s combined arms team would expose the enemy to the strength of another.[8]

- Orchestration. This tenet requires the deliberate arrangement of physical and non-physical actions to ensure their unified contribution to the mission. In doing so, orchestration enables simultaneity (or concurrent action) throughout the mission space, thereby negatively affecting the enemy’s decision-making capacity.[9] Orchestration slows the enemy’s ability to adapt as it struggles to respond to multiple friendly-force actions working in unison. The commander’s simultaneous actions are akin to taking two unified moves on the chessboard for the enemy’s single move.

- Mission command. This tenet encourages initiative in subordinate commanders to achieve a mission within the context of friction and uncertainty. In turn, mission command allows for faster decision-making and adaptation at each level of command.[10]

- Focus all actions on the centre of gravity. This tenet targets enemy vulnerabilities and avoids enemy strengths, all within the context of a centre of gravity that itself will change as opponents interact.

The tenets of manoeuvre warfare are designed, in part, to account for the unpredictability of a free-thinking enemy. When prepared and planned for in the relative safety of the headquarters, they are intended both to slow the enemy’s capacity for decision-making and to increase the speed achievable by the friendly force. And yet, when executed in the chaos of battle, the challenges inherent in achieving this outcome cannot be exaggerated. As opponents interact, order progresses towards disorder, making plans less relevant. These interactions of opposing forces produce a complex adaptive system – one with components that adapt and learn.[11] The behaviour of such a system is the outcome of a multitude of individual decisions made by the system’s opposing forces.[12] In such an environment, it becomes increasingly important that the commander learn and adapt more quickly than the enemy. Certainly, the slavish application of linear decisions made in planning without due consideration for how the other components of the system will react inevitably render the commander’s plan ineffective. Any effort to undermine an enemy’s centre of gravity will quickly lose relevance as the enemy responds by protecting its vulnerabilities and countering in turn. Therefore, the commander’s diligent focus not just on the tenets of manoeuvre warfare but also on how the centre of gravity and system itself will adapt is a principal concern.

The development of contingency plans is generally viewed as the most appropriate method to counter the uncertainty of an adaptive system. Generated in advance of the need to act, these contingencies are often articulated as ‘branches’ to the main line of operation (LOO)—a chronological sequence that illustrates the order in which Decisive Events (DEs) will be achieved by military effort.[13] Generally an outcome of the war game, the purpose of the branch is to increase options for decision-making and to support adaptation in the face of enemy action. Regrettably, contingency plans are inherently reactive, which is a characteristic inconsistent with manoeuvre warfare’s enduring requirement to achieve superior adaptation.

The Branch

While branches are intended to provide flexibility, and thereby to support the retention of the initiative in the face of possible enemy reactions,[14]their shortfall is that they generally rely on an enemy action and are thus a reactionary instrument. This is because branches attempt to balance the need for proactive adaptation against the risk of incorrectly predicting the enemy’s reaction. If the prediction is wrong and the ‘indicator’ that informs the decision to execute the branch is not observed, the branch becomes irrelevant and the commander can safely avoid applying military power and resources to the plan.

Importantly, the branch requires a ‘sensor’ to do this observing, and in turn report the presence of an indicator to the commander. Further, a suitable force needs to be prepared to execute the branch. Consequently, while proficient teams may achieve faster adaptation in the execution of the branch, the process that allows the branch to be activated is contingent on enemy activity. This does not mean that the branch is irrelevant—but it is reactive. As such, branches are at odds with the objective of manoeuvre theory, which seeks to create a ‘turbulent and rapidly deteriorating situation’ for an enemy.[15]

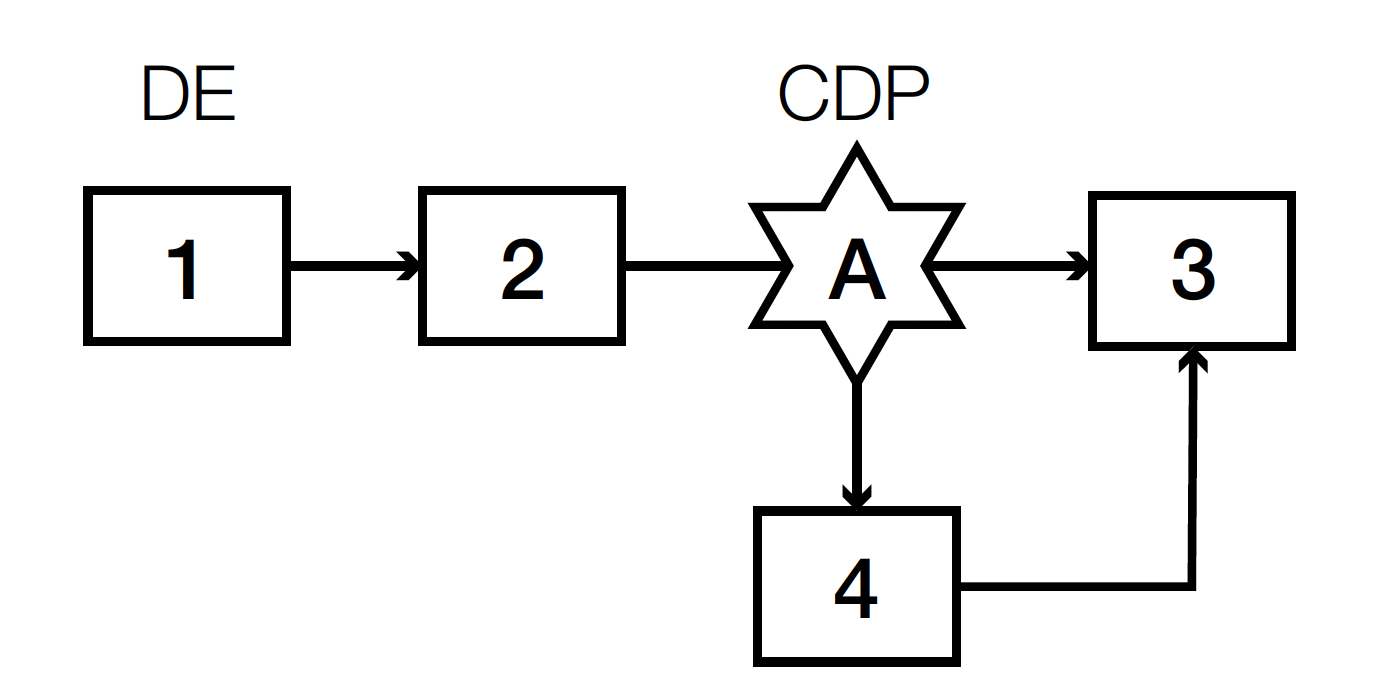

Moreover, a branch generally creates a consecutive rather than a simultaneous dilemma for the enemy. Therefore, branches do not afford the commander the opportunity for simultaneity, by which the enemy’s decision-making capacity may be overwhelmed.[16] Figure 1 is a representation of a LOO comprising two consecutive DEs leading to the commander’s decision point (CDP). The LOO is linear, whereby DE 1 and DE 2 are achieved in turn before the CDP, which may require the commander to commit to the branch and execute DE 4. While this LOO may achieve simultaneity through actions that do not amount to DEs, because of its linear nature this planning method is not fully consistent with tenets of manoeuvre warfare. A more deliberate and decisive attempt to orchestrate the events on the LOO would better achieve superior adaptation.

Figure 1. LOO with consecutive DEs and branch

The Emergent Decisive Event (EDE)

In contrast to the traditional linear planning method outlined above, introduction of the EDE during planning allows the commander to apply the tenets of manoeuvre warfare to a plan in a complementary but more proactive manner than the branch. In doing so, relative speed of adaptation is increased as the enemy’s decision-making capacity is deliberately slowed. The term ‘EDE’ is coined here to bring into sharper focus the benefits of orchestrating tactical actions in order to slow an enemy’s decision-making capacity. As mentioned, many of the underlying concepts will be familiar. This paper deliberately links them into a useful planning tool to assist planners and commanders alike.

The application of the EDE tool forces military planners to anticipate and plan to defeat the enemy’s most rational response to the achievement of a DE, as near as possible to the point in time at which the enemy would choose to implement this response. In doing so, this tool elicits the rapidly deteriorating situation sought by manoeuvre warfare, as the enemy’s most valid response to a decisive action on the battlefield is itself now defeated. This should not be confused with a supporting effort or nested task. While both are related to orchestration, the EDE is distinguished by its analysis of the enemy’s reaction, and its direct relation to the DE.

The author provides the following definition of an EDE:

An emergent decisive event is a decisive event that disrupts or dislocates the enemy’s most rational and adaptive response to a friendly achievement of a decisive event, and is executed at the point in time which the enemy would most likely choose to implement it. The emergent decisive event is thereby inextricably linked to the decisive event the enemy is likely to target and is orchestrated as such.

EDEs take their name from the complex adaptive system they are attempting to gain advantage over—the ‘emergence’ being the unpredictable outcome of a series of interdependent actions in a system.[17] The EDE is the event necessary to undermine the enemy response to the execution of the DE, having assessed the sum of previous decisions made by that enemy. An EDE is intended to be orchestrated with the DE it supports—that is, it is arranged in unified contribution to the mission.[18] Therefore, an EDE is predicated on the commander’s understanding of the probable enemy response to the execution of the nested DE. Should the EDE fail, the DE may also fail, and a CDP will be necessary to finally enact a branch, accompanied by a different DE.

Given that an EDE is likely to require the apportionment of critical resources by the commander, it is impractical to leave its formulation to the ‘course of action analysis’ step of the military appreciation process. While enemy reactions to friendly actions are best scrutinised during this stage of planning, by then forces will likely have been assigned and few will be available to support execution of the EDE. Rather, EDEs should be drafted when course of action concepts are initially developed, synchronised during ‘course of action development’, and then tested in ‘course of action analysis’. The application of centre-of-gravity analysis, which evolves within a complex adaptive system, will assist the commander to develop the initial EDE concepts.

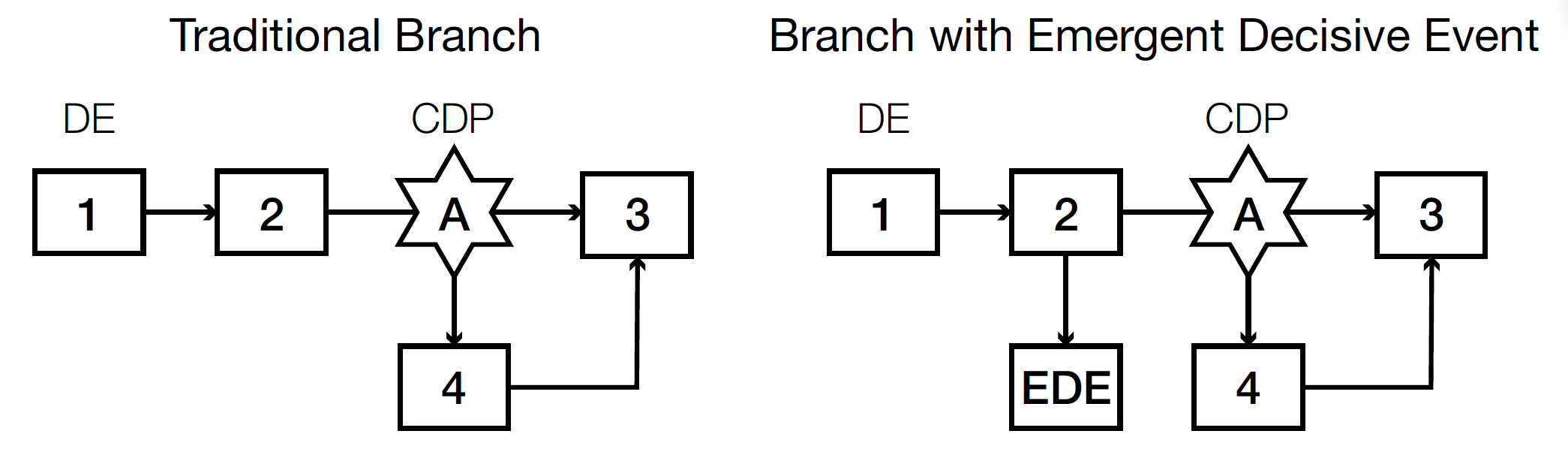

Figure 2. A traditional LOO at left, and the inclusion of the EDE at right

Figure 2 illustrates the difference between a standard LOO and one incorporating an EDE. The example on the left shows the branch enacted by CDP A, likely associated with a condition that DE 2 was unsuccessful. Conversely, in the example on the right, DE 2 is supported and orchestrated with an EDE, reducing the likelihood that the branch will be required.

Using the approach on the right, the EDE offers options to defeat the enemy’s probable response to DE, and reduces the likely need to execute a reactive CDP. It also creates an additional dilemma for the enemy commander, whose first reaction to DE 2 has failed, and who is now required to conceive and implement another action in a rapid and chaotic fashion. All the while, friendly forces have continued to retain the initiative and shape the battlespace in their favour.

First Pillar: An EDE is intended to be orchestrated with the DE it supports.

The need for simultaneity, or near simultaneity, between EDE and DE is paramount. In the example above, the commander will attempt to achieve this simultaneity by generating two dilemmas the enemy will be challenged to overcome. Doing so aims to paralyse the enemy’s capacity to achieve effective command and control through the creation of divergent multiple problems that produce an incoherent enemy response.[19] The enemy must believe that its response to the DE is a viable strategy at the time. If the EDE is executed too early, the enemy will adjust its response to the DE. If the EDE is executed too late, it will be irrelevant to the friendly LOO. Therefore the EDE should be executed as near as possible to the time of the DE and likely enemy response, in order to create the desired simultaneity in effect.

Second Pillar: The enemy must believe their response to the DE is a viable strategy at the time, and therefore the EDE should be executed as near as possible to the time of the DE.

To appreciate the value of the EDE, it is instructive to consider what could happen if it is not integrated into a LOO. Utilising the figure above, assume it is identified that the enemy would most likely undermine DE 2 with offensive support on friendly forces. Any reactive contingency by the commander to counter the enemy’s indirect fire inherently accepts some level of disruption from the enemy guns until the associated CDP is enacted. The delay is also likely to cause the friendly force to lose initiative and the enemy to gain decision superiority, at least temporarily. A far better option would be for the commander to execute an EDE that prevents the hostile battery from engaging in the first place.

Extending the example, while the traditional branch could achieve the same end state as the LOO with the incorporated EDE, there are some critical differences. Where the EDE likely dislocates or disrupts the hostile battery before it engages, the branch can only do so afterwards, potentially creating a dilemma for the friendly commander. As it occurs at the same time as DE 2, the commander’s use of the EDE also allows for the creation of two simultaneous dilemmas for the enemy (i.e. by destroying the enemy guns when DE 2 is executed), whereas the traditional branch achieves the same dilemmas consecutively, and only after another CDP determines which linear branch to follow. Thus, the EDE slows the enemy’s capacity to adapt, whereas the traditional branch fails to do so. Of most concern, the traditional branch risks the friendly commander’s decision superiority and initiative.

While the benefit of integrating EDEs has now been established, the challenge remains in accurately forecasting how an enemy will respond to a DE so that planners can develop an effective EDE. McCrystal argues that, in a complex system, accurate predictions are unachievable given the sheer volume of interactions that occur within that system.[20] But his assertion that ‘adaptive systems become more complex the longer the involved elements interact’[21] provides commanders with clues as to where to prioritise the application of military power and intelligence effort when developing the EDE. In the same way that it is easier to predict tomorrow’s weather than next year’s, a commander should anticipate that the accuracy of forecasts concerning enemy decision-making will decrease the longer that battle endures. For this reason, the commander should mitigate the risk of miscalculation by utilising EDEs for only the initial DEs on a LOO.

Limiting the application of EDEs in this way does not remove the challenge of accurately predicting enemy responses, but it does reduce the risk. By modestly forecasting how the enemy will evolve within the complex adaptive system in which it resides, early in the LOO, it is possible to formulate EDEs that characterise how the enemy will likely act at the time of DE execution. In the context of the example provided above, the enemy is most likely to react in accordance with its doctrine and usual behaviour, applied to the circumstances it faces on the battlefield. An enemy that disrupts attacks against its defensive position with offensive support, because that is what its doctrine states and that is how it has fought in previous wars, will probably do so in our example. However, if we apply the context that the enemy’s guns were destroyed in the deep battle, then perhaps the most likely response to attacks against its defensive position is to trigger the commitment of the enemy commander’s reserve. If this were the assessment, then the nested EDE could disrupt or dislocate this enemy’s reserve at the same time as the attack. Provided these assessments occur before the complexities and chaos of battle grow too great, the risk is likely to be more

tolerable.

Third Pillar: A commander should mitigate risk of miscalculation by utilising EDEs for only the initial DEs on a LOO, where the risk is likely to increase commensurately with the duration of the operation.

However, in circumstances where the risk of incorrectly predicting the enemy response is still too high to justify dedication of a friendly-force element to execute the EDE, the commander has the option of adjusting the defeat mechanism so that it still has utility to the overall mission. In the example provided above, a demonstration by friendly forces against the enemy’s reserve may well achieve physical dislocation, but so would a feint, with the added benefit of causing enemy attrition. In other words, while the commander cannot be certain how the enemy will act, depending on the circumstances lethal and tangible impacts on the enemy could be prioritised. This will increase the overall effectiveness of the EDE in the face of a miscalculation of the enemy’s response.

Historical Example of EDE Composition and Effectiveness—Battle of Pearl Harbor

Perhaps the most compelling example of the achievement of simultaneous dilemmas is provided by Thompson’s captivating version of Imperial Japan’s air attack on Pearl Harbor. The case study clearly illustrates how effectively the Imperial Japanese ‘Carrier Striking Task Force’, under command of Vice Admiral Nagumo, adhered to the planning pillars of the EDE concept as defined in this paper. The example demonstrates how the expectation of defeat was created in the mind of the US Commander Pacific Fleet, Admiral Kimmel, through the generation of an EDE.

Ultimately, Nagumo was able to successfully predict Kimmel’s most likely response to the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 and used this assessment to his advantage, thereby slowing Kimmel’s decision-making by creating simultaneous dilemmas. The successful way in which EDEs were applied is evident in the following narrative about the battle:

At 7.53am, Fuchida called out to his radio operator to transmit the code words ‘Tora! Tora! Tora!’—‘Tiger! Tiger! Tiger!’—to confirm that despite all of the uncertainties the element of surprise had been achieved ... Fuchida pulled the trigger on his flare gun to signal the fighter pilots to take control of the air while Lieutenant-Commander Shigeharu Murata’s slow moving torpedo-bombers made their first strike on Battleship Row.

At 7.57am, the commander of Patrol Wing 2, Lieutenant Commander Logan Ramsay, was standing in the Operations centre on Ford Island when he saw a plane diving over the station … Within the space of five minutes, aircraft at the army air bases of Hickam and Wheeler Fields, the naval air stations at Ford Island and Kaneohe Bay and the marine air base at Ewa had all been dealt mortal blows to prevent interference with the main business of the morning: the merciless torpedo-and-bomb attacks on the great leviathans of Battleship Row.

Kimmel radioed a message to every ship in the Pacific Fleet and to Admiral Stark in Washington: ‘Hostilities with Japan commenced with air raid on Pearl Harbor.’ Five minutes later he instructed Logan Ramsey at Patrol Wing 2: ‘Locate enemy force’, with the intention of taking the fight to the Japanese carriers. By then, however, Ramsey had only a handful of aircraft capable of getting airborne.[22]

When viewed through the lens of military planning and execution, it is evident that the pillars of the EDE were successfully applied by Nagumo at Pearl Harbor in the following ways.

First Pillar: An EDE is intended to be orchestrated with the DE it supports. Nagumo was primarily focused on Battleship Row, and the destruction of the ships moored there. But the attack on the airfields occurred almost simultaneously with the naval bombardment, which denied Kimmel the opportunity to use his most likely reaction force. If the attack on Battleship Row had been a DE defined as ‘at 7.53 am, functionally dislocate battleship manoeuvrability through torpedo-bomber attack while in dock’, then the nested EDE could have been ‘at 8.03 am, disrupt fighter aircraft based on Oahu with air-ground attack in order to support dislocation of battleships’. Conversely, had Nagumo instead planned for fighters to escort the torpedo-bombers, only to be diverted to the airfields if US fighters were observed launching (in accordance with a traditional and reactive branch), it is likely the attack on Battleship Row would have been less effective.

Second Pillar: The EDE should be executed as near as possible to the time of the DE it supports. Nagumo was able to achieve near-simultaneous dilemmas that Kimmel had to contend with through sequencing the attack on US airfields to occur approximately five minutes after the torpedo bombers commenced their attack on Battleship Row. Kimmel believed a fighter response was a viable strategy in response to the attack on the naval vessels, as evidenced by his order to launch fighters. However, he was yet to find out that his strategy was invalid and that he was now dealing with two dilemmas. If Nagumo had executed his strike on US airfields earlier in the day (creating consecutive rather than simultaneous dilemmas, as per a linear LOO), Kimmel would have likely responded differently to the attack on Battleship Row (assuming such an option was available to him).

Third Pillar: A commander should utilise EDEs for only the initial DEs on a LOO. If Nagumo had created another EDE for execution later in the attack on Pearl Harbor, the rapidly evolving situation would have likely made it irrelevant when the time to execute arrived. Indeed, predictions regarding US responses much later along the LOO would be at the mercy of chaos and chance. Under such circumstances, Nagumo would have been better served enacting the reactive branch at this point, rather than assigning valuable resources to an EDE that would likely become irrelevant.

In all, the case study demonstrates how Nagumo and his ‘Carrier Striking Task Force’ were able to create a simultaneous dilemma that effectively undermined Kimmel’s most probable response to the former’s DE. Having slowed Kimmel’s capacity to adapt relative to his own adaptive cycle, Nagumo created an expectation of defeat in his opponent. The outcome was inevitable:

[A] spent machine-gun bullet smashed the glass and struck him lightly on the chest, leaving a black smudge on his spotless white tunic. Kimmel picked up the bullet and told an aide, ‘It would have been merciful had it killed me’.[23]

Conclusion

In planning, a military’s emphasis on achieving quick adaptation alone unnecessarily constrains analysis. While this planning priority remains valid, relative adaptation superiority can be realised by orchestrating concurrent dilemmas for the enemy to contend with. This outcome can be achieved by generating an EDE that aims to dislocate or disrupt an enemy’s reaction to a DE. The EDE stands in contrast to the traditionally reactive branch developed during course of action analysis—these branches often being used to contend with the complexities that emerge in an evolving battlespace. The EDE also generates simultaneous dilemmas, whereas a branch only achieves them consecutively. The key distinguishing feature of an EDE is that it slows the enemy’s capacity to adapt. It does this by generating the opportunity for the friendly force to engage in deliberate, proactive manoeuvre that does not depend on conditions set by the enemy. To be successful, however, the EDE must be employed with consideration for the pillars mentioned above. By integrating the EDE into planning, the commander has the opportunity to achieve relative decision superiority. While acknowledging that many of the underlying concepts discussed here will be familiar to commanders, this article links them to deliberately achieve relative adaptation superiority. As history shows, by doing so, the turbulent and rapidly deteriorating situation sought by manoeuvre warfare can be achieved.

Army Commentary

Mahr’s piece on Emergent Decisive Event planning is worthy of consideration by any tactician. It is soundly based in good tactics as it addresses a most valuable goal for both combatants: seizing and maintaining the initiative by continuous action. Mahr argues correctly that too often in tactics we become objective focused rather than enemy focused, and often do not consider in sufficient detail an enemy response. We tend to react to an enemy response once it materialises rather than anticipating and pre-empting it by acting before it manifests. Instead of a constant action–reaction–counter-action cycle, Mahr argues for continuous action by a friendly force to compel an enemy to be constantly reacting. This approach is soundly based in manoeuvre theory and is also a sound and effective way to combat centralised fires-based theories of combat. When constant anticipation is coupled with constant action, the battlespace is always fluid, defeating efforts to understand it and then use a distant system to respond.

Mahr proposes that as we plan Decisive Events we also plan an attendant Emergent Decisive Event to complement the Decisive Event. This is where further analysis is warranted, as the very mechanistic and predictive nature of Decisive Event planning is itself at odds with the fluid nature of combat that Mahr proposes. I sense Mahr has either consciously or unconsciously identified this inherent contradiction when he sensibly warns that his concept does not work too far after the initial contact. He is right but has identified the wrong problem—the problem is Decisive Event planning itself. If instead Mahr were simply to argue that every action on the battlespace should anticipate an enemy reaction and put forces in motion to proactively pre-empt rather than reactively counter the enemy reaction, then I think his idea would still be retained but in a much simpler and more practical way, and would be a concept that continually holds true as an action unfolds.

Michael Krause AM

Major General

About the Author

Major Nicholas Mahr joined the Australian Army in 2010 and commissioned from the Royal Military College - Duntroon is an Artillery Officer. His professional interests include the study of strategy, tactics and counter fires. MAJ Mahr currently serves as Battery Commander of 105th Battery, 1st Regiment, Royal Australian Artillery.

Endnotes

[1] Australian Army, 2018, Land Warfare Doctrine 5-0: Planning (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia) (LWD 5-0), 9.

[2] S McCrystal, T Collins, D Silverman and C Fussell, 2019, Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World (Bungay, UK: Penguin Business).

[3] TF Madden, 2020, ‘What If Constantinople Hadn’t Fallen to the Turks?’, What If … Book of Alternative History (6th edition).

[4] ‘Battle of Austerlitz’, 2020, Britannica, at: https://www.britannica.com/event/Battle-of-Austerlitz

[5] ‘First Battle of Marne’, 2018, History, at: https://www.history.com/topics/world-war-i/first-battle-of-marne

[6] Australian Army, 2017, Land Warfare Doctrine 1: The Fundamentals of Land Power (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia) (LWD 1).

[7] Ibid.

[8] WS Lind, 1985, Maneuver Warfare Handbook (Boulder, CO: Westview Press).

[9] LWD 1.

[10] Ibid.

[11] JH Holland, 2006, ‘Studying Complex Adaptive Systems’, Journal of Systems Science and Complexity 19: 1–8, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11424-006-0001-z

[12] S Chan, 2001, Complex Adaptive Systems: ESD.83 Research Seminar in Engineering Systems, at: http://web.mit.edu/esd.83/www/notebook/Complex%20Adaptive%20Systems.pdf…;

[13] Australian Army, 2015, Land Warfare Doctrine 5-1-4: The Military Appreciation Process (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia) (LWD 5-1-4), 5-3.

[14] Ibid.

[15] LWD 1.

[16] Ibid.

[17] PM Dickens, 2012, Facilitating Emergence: Complex, Adaptive Systems Theory and the Shape of Change, PhD dissertation, Antioch University, at: https://aura.antioch.edu/etds/114

[18] LWD 1.

[19] Department of Defence, 2019, Australian Defence Force Procedures (ADFP) 5.0.1: Joint Military Appreciation Process (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia).

[20] McCrystal et al., 2019.

[21] Ibid.

[22] P Thompson, 2019, Pacific Fury: How Australia and Her Allies Defeated the Japanese (North Sydney: Random House Australia).

[23] Ibid.