The traditional security benefits conferred by Australia’s geography have been considerably reduced by the development of a Chinese long-range strike system capable of threatening Australian cities.[1] The myriad technologies that constitute this system can be applied across all domains and usually in combination. An understanding of these potential threats spurred assessments in the 2020 Defence Strategic Update and Force Structure Plan (FSP20) which signalled the requirement for greater Australian self-reliance.[2] This change has important implications for the Australian Defence Force (ADF)—most critically, the necessity to fight as a coherent joint force across multiple domains simultaneously at a scale unthinkable only a decade ago.

The ADF has taken important steps towards becoming a force that is both joint by design and joined in execution.[3] Headquarters Joint Operations Command (HQJOC) is in the second decade of its existence, the ADF routinely employs Joint Task Forces, and the annual training cycle is now convened as a Joint Warfare Series. These are supported by a Joint Capabilities Group and joint Force Design and Integration Divisions. These significant reforms ensure ‘jointery’ has greater influence than at any time in the ADF’s history. Nonetheless,

the ADF remains an inherently tactical force, dominated by single-service cultures and most comfortable providing domain-specific force packages to coalition operations. This must change if the ADF is to harness the potential of its warfighting capabilities as an integrated joint force in an increasingly contested security environment.

Despite the important reforms mentioned above, the ADF is still developing the joint character required to fully realise the benefits of the organisational changes and integrate them for enhanced multi-domain effect. In short, the ADF is still not joint enough to shape, deter and respond to the threats that must be anticipated as a result of increasing geopolitical tensions in the Indo-Pacific. This article argues that further reform is necessary to ensure ‘Joint’ is the ADF’s central organising principle in both word and deed. It argues that the joint force required by Australia’s degrading security environment must be underpinned by the creation and indoctrination of a joint culture that necessarily impinges on traditional service equities to maximise warfighting advantage. This joint culture is, in turn, essential to successfully designing and implementing the joint warfighting concepts necessary to bring coherence to the joint force’s preparedness for high-threat contingencies that may result from increased great power competition.[4] Finally, these concepts must be tested and refined through the ruthless application and primacy of a revamped joint command and control (JC2) system.

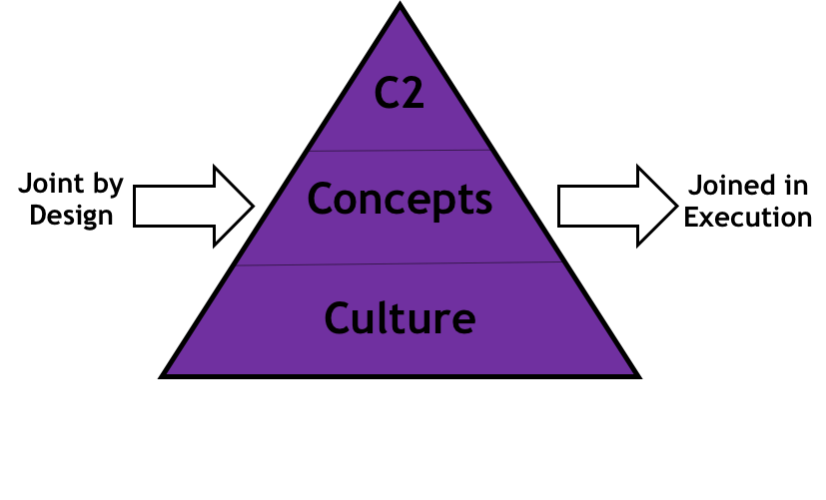

This article posits that the means for enhancing the ADF’s joint outcomes are best understood as a hierarchical model (Figure 1) where culture provides the foundation for joint concepts and command and control to emerge as the higher-order activities of ‘jointness’. Understanding the relationship between the tiers in this proposed hierarchy of joint integration offers a means to translate unity of purpose in force design into unity of effect in execution through creating and sustaining a joint warfighting ethos across the ADF.

A triangle is used to visualise this hierarchy because it makes explicit that joint command and control is the pinnacle of joint competence. However, the skills, knowledge and behaviours required for joint command and control to function cannot be attained without improving the ADF’s joint culture and concepts. As such, the model posits that the efficacy of the joint force is enhanced or undermined by the virtuous or vicious interactions of each tier: joint culture can be enhanced by the sustained application of effective concepts directed by visionary joint command and control, but the inverse is also true. Critically, joint concepts and joint command and control cannot function without robust joint culture as a baseline. This article concludes that the ADF’s successful integration (or otherwise) of these factors will be most obvious at the operational level, emphasising the importance of HQJOC in the Australian context.

Figure 1. The hierarchy of joint integration

Joint Culture[5]

Recognising the multi-domain potential of the advanced capabilities flagged in FSP20 relies on the efficacy of ADF joint culture. The ADF’s new mission is ‘To apply military power in order to defend Australia and its national interests’. This is a joint mission requiring a joint warfighting culture. It is valuable, therefore, to understand why joint culture is important, as well as the obstacles that impede its development.[6]

‘Joint’ is a warfighting philosophy that enhances multi-domain outcomes by maximising the strengths and protecting the weaknesses of each domain owner’s contribution. Successful joint warfighting requires a foundation built on domain-specific experience. Nonetheless, a joint approach aims to create new military options and effects by using and prioritising single-service capabilities in innovative ways to dislocate adversary expectations.[7] A joint culture must sit above single-service cultures as a means to embrace and encourage diversity of thought and experience to drive military innovation. Contemporary joint culture must also account for the contribution of the public service workforce who deliver many of the effects relied upon by the ADF to enable advanced capabilities to function.[8] This requires meaningful and sustained engagement between uniformed and civilian personnel at the tactical and operational levels to practise the employment of discrete capabilities (cyber, space, intelligence, health etc.) and build the trust necessary to effectively utilise them in a warfighting context. Service identity and culture will always be important, but a joint culture must predominate if the ADF is to integrate service and other government capabilities in less tribal ways.[9]

Achieving this requires the ADF to recognise the limitations of single-service bias and its detrimental impact on harnessing multi-domain potential. Service-specific cultures are highly effective in achieving single-domain mastery. They are akin to orchestras playing magnificent but well-established symphonies. Joint culture, in contrast, should take its lead from jazz by subverting established norms through the use of random combinations of capabilities and effects to create new and unexpected harmonies. An innovative joint culture must be unconstrained by service-specific bias and provide the transformational impetus to create multi-domain ‘mash-ups’ that dislocate an adversary’s expectations and create surprise.[10] Robert Leonhard argues single-service bias creates ‘protective’[11] rather than ‘dislocative’[12] designs for battle. This results in armies, navies and air forces planning and training to defeat counterpart services rather than examining how to dislocate adversaries in different domains.[13] A joint culture, in contrast, should be focused on gaining asymmetric advantage through orchestrating the employment of single-service capabilities to achieve cross-domain effects.

Research indicates that despite the potential benefits, establishing and sustaining an overarching joint culture is not easy. Eric Dane highlights that domain expertise limits ‘adapt[ability] to new rules and conditions’ and ‘when task conditions change … an expert’s [habits] may be incommensurate with the altered nature of the situation’.[14] In short, as domain-specific expertise is acquired, flexibility can be lost and creativity stifled. Dane terms this ‘cognitive entrenchment’. If domain experts can be slow to adapt to changing circumstances due to their depth of expertise, the challenge for recognising the potential of the joint force is capitalising on single-domain expertise before cognitive entrenchment takes hold.[15] Paradoxically, this means harnessing the best of single-service culture with the express intent of creating a joint version that reduces the influence of the parent cultures from which it was drawn. This is challenging when those charged with generating joint outcomes are generally domain-specific experts whose advancement is the result of demonstrated excellence within their parent service and to whom joint culture may offer an implicit challenge.[16]

Joint culture must, therefore, be supported and inculcated by enhanced joint literacy developed throughout a career. The Joint Professional Military Education (JPME) Continuum plays a crucial role but must be supported by continuous reinforcement and employment opportunities—something that is haphazard in the ADF’s current approach to developing joint warfighting competence.[17] Moreover, while promotion is controlled by the services, domain-specific bias will continue to limit opportunities to grow joint-focused professionals. Therefore, a review of career management is likely to be as important as JPME for joint culture to take root.[18] This could see the ADF identify officers with an aptitude for joint operations and carefully manage them outside of service strictures to spearhead cultural change before cognitive entrenchment takes hold.[19]

This foreshadows the establishment of a warfighting-focused joint staff possessing the necessary military acumen, cultural fit and innovative approach required to enhance joint outcomes and ensure the permeation of joint culture throughout the ADF through careful career management. This idea draws inspiration from Moltke the Elder and his creation of the Prussian General Staff in the mid-19th century. This innovative staff created a comparative advantage for Prussia when competing against outdated models employed by peer armies. As Michael Howard explains (emphasis added):

[W]artime command and control [needs] greatly increased. In the French, Austrian, and British armies staff officers … became little more than military bureaucrats … Moltke, on the contrary, turned them into an élite, drawn from the most promising regimental officers, trained under his eye and alternating in their careers between staff and command posts of increasing responsibility.[20]

In the Australian context, this cadre of joint staff would focus on ensuring the ADF is greater than the sum of its parts, rather than an inefficient aggregation of them. They may not be masters of parent service warfighting but would represent the cognitive agility (rather than entrenchment) required to synthesise domain-specific orthodoxy for asymmetric multi-domain effect. This should, at least initially, occur at the operational level where joint coordination is most critical—emphasising HQJOC’s centrality to the emergence of joint culture throughout the ADF.

Joint experience enables joint culture to take root. Few, however, have the chance to serve in HQJOC or participate in the joint component of exercises like Talisman Sabre. Absent the muscle memory resulting from regular joint endeavours, individuals will understandably cohere around service tribalism.[21] The challenge, therefore, is scaling the ADF’s limited joint experience across the force through other activities. Culture is essential to this by ensuring more ADF personnel are predisposed to joint outcomes and conversant with the latest joint concepts. This joint literacy would be greatly aided by the establishment of more mechanisms to facilitate professional discourse about joint warfighting. To complement service publications and the Australian Journal of Defence and Strategic Studies, the ADF would benefit from sponsoring a journal like the United States’ Joint Force Quarterly. This publication is charged by the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff to ‘inform and educate national security professionals on joint and integrated operations’ and focuses on the operational employment of the joint force, rather than the strategic and political conditions that may require it to be deployed.[22] Incentivising and sustaining similar professional discourse for the ADF will be critical to developing the whole-of-force competence in joint multi-domain warfighting required to succeed in the contemporary operating environment.

Attempts to enhance joint culture must not, however, discount the importance of territorial feelings and behaviours associated with service identity. To do so is to overlook the importance of single-domain expertise to informing joint planning and execution.[23] Instead, the key for enhancing joint culture is ensuring collective ownership over new outcomes, enabled by transformation agents who represent their service lineage but are collaborative and innovative enough to avoid parochialism.[24]

Joint Concepts[25]

Australia lacks an executable joint warfighting concept. Currently, there is no baseline from which to test and adjust how the joint force will conduct multi-domain operations to defeat an adversary. Notwithstanding the significant changes to the ADF’s capstone doctrine series, ADF joint doctrine remains largely procedural and lacks the operational detail required to visualise the application of joint resources in a contemporary conflict. This is a critical gap in our intellectual preparation for war and compels individual learning about others’ joint experiences in an attempt to contextualise them for Australian circumstances. These efforts provide important perspectives to help shape joint operations, but even jazz musicians need a common reference point from which to build a harmony. What differentiates joint concepts from service or capability specific concepts is, therefore, the vision they offer for integrating and cohering silos of excellence to achieve asymmetric advantage through layering multi-domain effects.

The maritime, littoral geography and escalating tensions between powerful state actors that characterises the contemporary Indo-Pacific provides a powerful forcing function for joint conceptual development. Regardless of the challenges of this terrain and the accelerated fielding of advanced military capabilities, the Indo-Pacific offers great potential to explore the integration of joint capabilities. For example, only a joint concept can adequately consider how army and navy capabilities might disrupt adversary air forces to open temporal manoeuvre corridors for friendly air and cyber forces to operate. This type of analysis is the acme of joint warfighting: determining how the services can employ their capabilities to disrupt or dislocate a potential adversary’s freedom of action in other domains to create opportunities or shield vulnerabilities. Meaningful visualisation and description of these actions is the realm of joint concepts—they articulate how the ADF will be joined in execution. The validity of these concepts will reflect the successful adoption (or otherwise) of the joint culture described above.

Concepts are theories for success in war. They provide options for solving new problems, drive future doctrine and overturn current orthodoxy through testing and experimentation. In so doing they change warfighting approaches through intellect rather than as a result of ‘bloody empiricism’.[26] A useful historical precedent is the United States Navy’s preparation for conflict in the Pacific prior to the Second World War. Here, the Navy’s peacetime adaptation towards carrier-based warfare allowed it to overcome the decimation of its battleship fleet at Pearl Harbor. These preparations allowed the Navy to severely curtail Japanese blue-water ambitions and strategic flexibility at the Battle of Midway only six months later.[27]Carriers forced naval officers to think in terms of fighting a distant maritime war in the absence of the bases that traditionally enabled power projection at scale. The resulting design and testing of new operational concepts strengthened the capacity of the entire organisation to adapt to new circumstances.[28]

Many of these concepts and platforms matured during the Pacific campaign. Nonetheless, they were conceived of and embedded within the Navy’s collective consciousness during the interwar period. This included annual war gaming at the Naval War College that led to consistent refinement of War Plan Orange—the United States’ peacetime planning for conflict with Japan.[29]

While this is a single-service example, it drove the employment of America’s joint capabilities within the Pacific Theatre and demonstrates the importance of Australia’s joint force pre-empting rather than responding to changes in the character of war. It also reinforces that adaptation is best enabled by focusing on a real and defined threat scenario. This is a lesson of particular relevance to Australia’s joint multi-domain concept development in light of the emergence of a Chinese long-range strike system capable of holding Australian infrastructure and ADF assets at risk at significant range.[30]

Australian concepts must recognise that multi-domain warfare is inherently joint but vulnerability exists in the seams where domain ownership is unclear or contested.[31] As David Deptula argues:

[S]ervices tend to develop capabilities in a stand-alone manner focused around their primary operating domain without an overarching construct to ensure joint … interoperability. This leads to strategies focused on deconfliction [rather than] the interdependence required to achieve force multiplying effects with available resources.[32]

Interdependence is about recasting single-service orthodoxy to create joint concepts that allow the ADF to act differently by using extant means in new ways through asking different questions. Component-level planning seldom achieves this. A professionalised joint staff is the only place where these potential synergies, born of diverse backgrounds and experience across different capabilities, can be assembled conceptually.

An iterative process of concept development can drive joint force design and collaborative procurement by back-casting from how we envisage the joint force will execute the multi-domain fight.[33] These joint warfighting concepts, ideally endorsed by the Chiefs of Services Committee, can provide the services with clarity as to the role they are expected to play within specified scenarios. As the previous Commander of the United States Indo-Pacific Command argued, this drives explicit prioritisation of capabilities based on joint force need,[34] rather than a domain owner’s preferred way of fighting. For example, clarity on the role of the land force through an endorsed joint concept could provide fresh impetus to review the need for a new armoured vehicle fleet when expanding investment in land-based anti-ship missiles and air defence capabilities might be a more important requirement for the joint force.[35] The absence of this agreed vision for how the ADF should fight ensures the joint force cannot coalesce around a common reference point, and reinforces the ongoing post-procurement integration challenges that result from stovepiped capability development.[36]

Joint Command and Control (JC2)[37]

Joint command and control is the core warfighting competency of a professional force. It requires a systemic approach that includes the people, processes, authorities and delegations, communications systems and infrastructure required to turn concepts into actions.[38]Effective joint culture and concepts are the basis for realising the potential of the joint force, but JC2 is the tangible means through which the ADF ensures it is joined in execution. The unified approach to command and control this implies will be critical in an era where technology offers the potential to visually represent a single warfighting environment. These visualisation tools blend traditional service-based approaches to battlespace understanding into a single, multi-domain picture within which a Commander is able to understand and act with enhanced agility.[39]

This portends profound changes to joint command and control if the ADF is to maximise the potential of the military capabilities envisaged in FSP20. Emerging technologies, including future strike capabilities, will require a tightly coupled JC2 system that synchronises ADF, whole-of-government and allied capabilities at machine speed to position them in the right space, at the right time, to enable the desired military effect. This demands unity of effort across domains. It also implies the centralisation of key authorities at the operational level and may require a theatre commander to direct certain tactical capabilities and actions to ensure synchronised delivery of military and non-military effects across multiple domains. This requires the flattening of coordination mechanisms between echelons rather than the 39 decentralisation of effects delivery.[40]

Directive control, the precursor to what the ADF considers Mission Command, resulted from massed armies exceeding the ability of a single commander to understand and manage subordinate manoeuvre. Thus, a disaggregated approach became necessary. However, this could work against the tightly coupled multi-domain effects required to operate across highly contested, interconnected physical and virtual terrain.[41] Ironically, the modern quest for seamless, networked, stand-off combat power may reverse the disaggregation trend, increasing the importance of a centralised joint force commander directing activity from the operational level.[42] Today, a joint commander coordinating military actions across multiple domains is likely to have superior situational awareness to that of any subordinate, domain-specific commander. Yet, while the paradigm might be shifting, this is not the end of directive control. The challenge for the joint command and control system is to ensure shared understanding across distributed nodes so that subordinate commanders can access information that is (if imperfect) similar to that available to the joint commander, to facilitate unity of action.[43] This requires a redundant, survivable JC2 backbone that links theatre effects with tactical actions at critical points in time and space.

Accepting that communications may not be available at the point of engagement, the JC2 system must also be capable of orchestrating the desired effects in advance of the physical contest to enable execution in a denied environment. This does not reduce the requirement for joint forces to act in a coordinated manner. Rather, it reinforces the importance of clear guidance to subordinate commanders about where to be, what must be achieved, at what time(s) to maintain synchronisation of effects delivery. Success will still rely on the initiative and flexibility of subordinate commanders, but their freedom of action may be constrained to optimise multi-domain outcomes.

The United States military is experimenting with Joint All Domain C2 (JADC2) to implement its warfighting concepts.[44] JADC2 ‘raises difficult questions regarding who has decision authority and risk acceptance’ as it challenges traditional component command structures which ‘tend to exacerbate … service and domain stovepipes … resistant to ceding control over their assets’.[45]These challenges are not unique to America. In Australia, component-style C2 still predominates based on the influence of the services. Unfortunately, the presumption of pervasive domain mastery inherent in this construct provides a disincentive for cross-service collaboration on military problems which are inherently multi-domain in nature.

For a small force this is problematic, particularly where joint concepts will demand a command and control system capable of synchronising and orchestrating capabilities across domains in real time to achieve the desired effects.[46] The experience of Combined Joint Task Force (CJTF) Mountain during Operation ANACONDA in 2002 is instructive here as it demonstrates how a component mindset can hinder a joint approach. Despite its title, the CJTF prepared and fought like a land component, failing to adequately consider how to integrate air-delivered effects to enable manoeuvre. When circumstance dictated that the best means to disrupt the enemy was by air, with land forces in support, the headquarters was ill-prepared to adopt the required approach, resulting in unnecessary friction and operational risk.[47] This provides a useful example of how traditional domain-specific approaches to command and control can inadvertently limit the employment of available joint resources.

The objective of a future JC2 system should be the ability to ‘aggregate, reconfigure, and disaggregate’ the joint force rapidly, without losing tempo.[48] JC2 is, therefore, an integrating function allowing speed of decision through flattened structures that achieve the optimal combination and synchronisation of effects.[49] Truly joint command and control requires trust in, and knowledge of, other services but cannot allow single domain biases to predominate. In the contemporary Australian context, rather than incentivising unified execution, the hybrid command and control model employed at HQJOC continues to entrench single-domain primacy by accommodating an unwillingness of the services to cede operational control. This suggests the absence of the joint culture described above. It also hints at a lack of maturity in the ADF’s command and control system if components are unable to trust the operational headquarters or its subordinate JTFs to directly control all forces operating within a given operational area.[50] This is an inefficient approach the ADF can ill afford, where multiple layers of redundant command and control retard rather than enable tempo. This tension underscores the importance of getting the ADF’s approach to joint command and control fit for purpose well in advance of conflict.

Finally, for the JC2 system to achieve decision advantage in environments that will continue to be dominated by friction, chaos and chance, an agile approach will obviously be necessary—but this agility relies on a supremely well-trained staff.[51] Therefore, success for JC2 is dependent on the ability to baseline the requirement and train it across the joint force to ensure consistency in approach and application.[52] For the ADF, the best place to define the requirement and adjust the design of the joint command and control framework is likely to be HQJOC. By designing JC2 based on the operational commander’s needs as the joint force employer, a common approach can be incorporated vertically and horizontally throughout the ADF. The success of this approach will, however, rely on the efficacy of the culture and concepts that underpin it.

Conclusion

The ADF is not joint enough for the challenges it is likely to face, but it can be. Ensuring the ADF is greater than the sum of its parts requires a paradigm shift with implications for training, doctrine, personnel management and warfighting philosophy. An integrated joint force must be built on a compelling joint culture that facilitates the design of optimal warfighting concepts and ensures execution is possible through visionary joint command and control.

The hierarchy of joint integration offers one possible conceptual model through which to enhance the ADF’s multi-domain acumen. It provides a framework for consolidating the robust joint ethos required to ensure a force joint by design is unified in execution. The operational level presents the logical hub to maximise the benefits of this approach, acting as a nexus for enhancing multi-domain warfighting. This highlights the criticality of a well-resourced operational-level headquarters to ADF reform efforts. However, HQJOC’s ability to inform joint concepts and execute through joint command and control relies on whole-of-ADF efforts to build the culture necessary for the joint force to thrive in an increasingly hostile geopolitical climate.

Ultimately, recognising the ADF’s multi-domain potential requires greater acknowledgement of the limitations of traditional service-focused approaches, particularly by the services themselves. As a result, further reductions in single-service influence are likely to be necessary to ensure the absolute primacy of joint warfighting outcomes when developing the ADF’s approach to cultural reform, concept development and command and control.

Army Commentary

Many themes in Lieutenant Colonel Gilchrist’s paper are now reality for the ADF. These include the 2022 publication of Integrated Campaigning, the ADF’s capstone concept, which guides the ADF to ‘work with others to achieve more’. Importantly, Integrated Campaigning aspires for an ADF that is the same by default, separate by necessity, and, similar by exception.

In addition, in 2022, the ADF agreed a joint framework connecting policy and strategy with ADF concepts. This Joint Concepts Framework includes Integrated Campaigning. It then sequences the ADF Theatre Concept, ADF Functional Concepts and five domain concepts: maritime; land; air; space; and cyber. The planned paramount ADF Functional Concept, as an integrating system for the ADF, is command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, and electronic warfare (C4ISREW). Together, all concepts are designed to unify the ADF and enable Australian security.

Within these concepts is a codification of ADF guidance, including principles for ADF interoperability, mission engineering, mission threads and operational abilities. This guidance, connecting strategy and tactics, informs the design of ADF experimentation, capabilities, programs, sub-programs and projects. Finally, ADF guidance also interacts with operational art through campaign plans designed, developed and executed by Joint Operations Command.

LTCOL Mark Gilchrist’s article is an excellent example of loyal dissent. This type of dissent, currently a topic of debate within the United States Marine Corps, is where service members can criticise their organisation while remaining loyal to the same organisation. The proof of LTCOL Gilchrist’s loyal dissent is that so many of his ideas are now reality for the ADF.

Chris Field, DSC, AM, CSC

Major General

About the Author

Lieutenant Colonel Mark Gilchrist is an Australian Army officer with Joint Force experience at the tactical, operational and strategic levels of defence. LTCOL Gilchrist is a graduate of the Australian Command and Staff College (Joint) and an Art of War alumni.

Endnotes

[1] Malcolm Davis, ‘Why Australia Needs a Long-Range Air Defence Capability’, The Strategist, 26 February 2020, accessed 20 August 2020, at: https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/why-australia-needs-a-long-range-air-defence-capability/

[2] Shmuel Shmuel, ‘The American Way of War in the Twenty First Century: Three Inherent Challenges’, Modern War Institute website, 30 June 2020, accessed 28 August 2020, at: https://mwi.usma.edu/american-way-war-twenty-first-century-three-inherent-challenges/; and Van Jackson, ‘The Risks of Australia’s Solo Deterrence Wager’, War on the Rocks, 20 July 2020, accessed 28 August 2020, at: https://warontherocks.com/2020/07/the-risks-of-australias-solo-deterrence-wager/

[3] Tim McKenna and Tim McKay, 2017, Australia’s Joint Approach: Past, Present and Future, Joint Studies Paper Series, No. 1 (Canberra: Defence Publishing Service), 1–2.

[4] Oriana Skylar Mastro, ‘The Taiwan Temptation: Why Beijing Might Resort to Force’, Foreign Affairs, July/August 2021, accessed 8 June 2021, at: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2021-06-03/china-taiwan-war-temptation?

[5] Geert Hofstede, 1997, Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind (New York: McGraw Hill).

[6] McKenna and McKay, 2017, 76.

[7] James Goldrick, 2010, ‘Thoughts on JPME’, Australian Defence Force Journal, no. 181: 8.

[8] McKenna and McKay, 2017, 76.

[9] S Rebecca Zimmerman, Kimberly Jackson, Natasha Lander, Colin Roberts, Dan Madden and Rebeca Orrie, 2019, Movement and Maneuver: Culture and the Competition for Influence Among the U.S. Military Services (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation), accessed 18 August 2020, at: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2270.html

[10] Joshua Cooper Ramo, 2009, Age of the Unthinkable: Why the New World Disorder Constantly Surprises Us and What We Can Do About It (New York: Little, Brown and Company), 128–129.

[11] Pitting one’s strengths against those of a like-domain counterpart.

[12] Using one’s strengths against the weakness of an unlike-domain counterpart.

[13] Robert R Leonhard, 2017, Fighting by Minutes: Time and the Art of War (San Bernadino, CA: Praeger), 54–55.

[14] Eric Dane, 2010, ‘Reconsidering the Trade-Off Between Expertise and Flexibility: A Cognitive Entrenchment Perspective’, Academy of Management Review 35, no. 4: 581, 585.

15 Ibid., 581, 585.

[16] Ibid., 586; and Nathan P Freier and John H Schaus, 2020, ‘INDOPACOM through 2030’, Parameters 50, no. 2: 27–28.

17 Australian Defence College, 2019, The Australian Joint Professional Military Education Continuum (Canberra: Defence Publishing Service).

18 Richard Barrett and Steve Ditulio, ‘One Defence Needs One Performance Report’, The Forge, 3 June 2020, accessed 18 August 2020, at: https://theforge.defence.gov.au/publications/one-defence-needs-one-performance-report

[19] Dane, 2010, 589.

[20] Michael Howard, 2009, War in European History (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 101.

[21] McKenna and McKay, 2017, 100.

[22] Taken from the Joint Force Quarterly website, at: https://ndupress.ndu.edu/JFQ

[23] Graham Brown, Thomas B Lawrence and Sandra L Robinson, 2005, ‘Territoriality in Organisations’, Academy of Management Review 30, vol. 3: 577.

[24] Steven M Gray, Andrew P Knight and Markus Baer, 2020, ‘On the Emergence of Collective Psychological Ownership in New Creative Teams’, Organization Science 31, no. 1: 141.

[25] A description of how a joint force commander might plan, prepare, deploy, employ, sustain and redeploy a joint force. It guides the further development and integration of joint functional and service concepts into a joint capability, and articulates the measurable detail needed for experimentation and decision-making. As defined in Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms (US Department of Defense, 2005), accessed 7 September 2020, at: https://www.thefreedictionary.com/joint+concept

[26] Leonhard, 2017, xvii.

[27] George Baer, 1994, ‘The Early Offensive in the Pacific’ and ‘Pacific Command’, in One Hundred Years of Sea Power: The U.S. Navy, 1890-1990 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press).

[28] John T Kuehn, 2010, ‘The U.S. Navy General Board and Naval Arms Limitation: 1922–1937’, The Journal of Military History 74, no. 4: 1160.

[29] Ibid., 1135–1137, 1160.

[30] Malcolm Davis, ‘China’s Long-Range Missiles highlight RAAF’s Strike Shortcomings’, The Strategist,4 June 2021, accessed 7 June 2021, at: https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/chinas-long-range-missiles-highlight-raafs-strike-shortcomings/

[31] Ray Griggs, ‘Building the Integrated Joint Force’, The Strategist, 7 June 2017, accessed 20 August 2020, at: https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/building-integrated-joint-force/

[32] David Deptula, ‘Moving Further into the Information Age with Joint All-Domain Command and Control’, C4ISRNET, 9 July 2020, accessed 25 August 2020, at: https://www.c4isrnet.com/opinion/2020/07/09/moving-further-into-the-information-age-with-joint-all-domain-command-and-control/

[33] Itai Brun, 2010, ‘The Second Lebanon War, 2006’, in John Andreas Olsen (ed.), A History of Air Warfare (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press), 328–330.

[34] Admiral Philip S Davidson, ‘Transforming the Joint Force: A Warfighting Concept for Great Power Competition’, speech delivered in San Diego, 3 March 2020, transcript on U.S. Indo-Pacific Command website, accessed 15 August 2020, at: https://www.pacom.mil/Media/Speeches-Testimony/Article/2101115/transforming-the-joint-force-a-warfighting-concept-for-great-power-competition/

[35] Michael Shoebridge, ‘Setting Clear Priorities for the ADF Requires Ruthless Decisions on the Force We Build’, The Strategist, 5 August 2021, accessed 26 August 2021, at: https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/setting-clear-priorities-for-the-adf-requires-ruthless-decisions-on-the-force-we-build/

[36] McKenna and McKay, 2017, 63, 77.

[37] The exercise of authority and direction by a properly designated commander over assigned and attached forces in the accomplishment of the mission. Command and control functions are performed through an arrangement of personnel, equipment, communications, facilities, and procedures employed by a commander in planning, directing, coordinating and controlling forces and operations in the accomplishment of the mission. From US Department of Defense, 2013, Joint Publication 1: Doctrine for the Armed Forces of the United States (25 March 2013) V-14, accessed 8 September 2020, at: https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/Doctrine/pubs/jp1_ch1.pdf?ver=2019-02-11-174350-967#page=126

[38] US Department of the Army, 2019, ADP 6-0: Mission Command: Command and Control of Army Forces (Washington: Army Publishing Directorate, July 2019), 4-1, accessed 20 August 2020, at: https://fas.org/irp/doddir/army/adp6_0.pdf

[39] Griggs, 2017.

[40] Leonhard, 2017, 229.

[41] Ibid., 143–145, 154–157.

[42] Trent J Lythgoe, 2020, ‘Beyond Auftragstaktik: The Case Against Hyper-decentralised Command’, Joint Force Quarterly 96, accessed 28 August 2020, at: https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Media/News/News-Article-View/Article/2076032/beyond-auftragstaktik-the-case-against-hyper-decentralized-command/

[43] BA Friedman and Olivia A Garard, ‘Technology-Enabled Mission Command’, War on the Rocks, 9 April 2020, accessed 2 September 2020, at: https://warontherocks.com/2020/04/technology-enabled-mission-command-keeping-up-with-the-john-paul-joneses/

[44] Congressional Research Service, ‘Defence Capabilities: Joint All-Domain Command and Control (JADC2)’, In Focus, 6 April 2020, accessed 25 August 2020, at: https://fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/IF11493.pdf

[45] Deptula, 2020.

[46] Douglas O Creviston, 2020, ‘Transforming DOD for Agile Multidomain Command and Control’, Joint Force Quarterly 97, accessed 1 September 2020, at: https://www.whs.mil/News/News-Display/Article/2132958/transforming-dod-for-agile-multidomain-command-and-control/

[47] Benjamin S Lambeth, 2010, ‘Operation Enduring Freedom’, in John Andreas Olsen (ed.), A History of Air Warfare (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press), 275–285.

[48] US Department of Defense, 2012, Capstone Concept for Joint Operations: Joint Force 2020 (Washington, 10 September 2012), 5, accessed 16 August 2020, at: https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=TE0QBrSPdNA%3D&portalid=10

[49] Leonhard, 2017, 150.

[50] Andrew Balmaks, Justin Kelly and JP Smith, 2013, Strategic Command and Control Lessons—Scoping Study (Noetic Solutions), 15, accessed 12 August 2020, at: https://cupdf.com/document/final-report-department-of-defence-of-this-report-is-at-his-discretion-authors.html

[51] Lythgoe, 2020.

[52] Defence Science and Technology Group, 2020, Agile Command and Control Factsheet (Canberra: Defence Publishing Service, August), accessed 2 September 2020, at: https://www.dst.defence.gov.au/strategy/star-shots/agile-command-and-control