Professor You Ji

Head of Department of Government, University of Macau

The Indo-Pacific (Indo-Pacific) idea has been around for over a decade. Professor Rory Medcalf raised it as a policy suggestion years ago but the concept remained only academic.1 Japanese Prime Minister Abe enriched the concept with a component of democratic arch but it was more visionary than substantial as the countries placed their concerns of national interests above the ideational preferences. It was not until President Trump embraced the idea in late 2017 did the notion become a practical policy guide for the US and its allies/partners in the three continents of Asia, Oceania and North America to adjust to its new geo-strategic dynamics. As far as this paper is concerned the core of the Indo-Pacific strategy, as now frequently depicted by key defence leaders and security experts in the Indo-Pacific, is the emer- gence of the Quad (Quadrilateral Security Dialogue)—America, Australia, Japan and India. Based on common threat perceptions and shared interests in certain defence realms, in meeting the new challenges of the changing international order they seek new impetus to construct an informal but cohesive military mechanism, somewhat transcending the traditional bilateral alliance framework. For the purposes of this paper this creates new dimesions of defence cooperation with a nexus of land conflicts and maritime tensions in the Indo-Pacific. Therefore under the Indo-Pacific strategy neither an army nor a navy could develop in isolation in terms of military transfor- mation and war preparation. Future land warfare may be integrated into a broader context of joint warfare that will reset the region’s officer mentality, war planning and defence posturing. This paper will largely use the case study of land force application in China and India in response to the new Indo-Pacific challenges.

The Indo-Pacific strategy: Shaping a New Regional Defense Landscape

The US naming China as a peer rival in its National Security Strategy and National Defense Strategy in 2017 provides proof that explains why Wash- ington took over the Indo-Pacific idea almost all of a sudden. Clearly this added value to the original conceptual construction and reflects the state of power transition due to Sino-American competition. China’s assertive protection of its sovereignty claims and its Belt-and-Road Initiative (BRI) is reshaping the Eurasian geopolitical and geoeconomic order in due time. The concerned powers may have realized that some collective response is necessary.2 Here a few questions need to be raised whose answers would enhance our understanding of the Indo-Pacific ideas and strategy.

Understanding the Nature of the Indo-Pacific Strategy

The first question is what the nature of the Indo-Pacific strategy is. Different nations in the related regions may have different views on the Indo-Pacific concept. Through long association with the initiators of the Indo-Pacific strategy, I tend to see it from a strategic and defence angle. First of all, the Indo-Pacific strategy has great military significance. The US military has as- sociated it with its combat doctrines such as the air-sea battle, especially in terms of SLOC (sea lines of communication) warfare from the Indian Ocean to the South Pacific. Under such a guidance the US Indo-Pacific Command has extended its two traditional island-chain defence lines from the West Pacific to the Indian Ocean and pivoted US forward deployment in the Indo- Pacific regions in a more combat-oriented fashion. Australia has also gradu- ally projected more military presence in the western Pacific and the Indian Ocean. The Australian Defence Force now conducts more joint war drills in Asia than at any time before. One telling example is that Canberra has raised its security relations with Tokyo to one of a military/defence sub-alliance.3

In response, China has executed westward military expansion. The People’s Liberation Army-Navy (PLA-N) has recently adopted a new two-ocean maritime strategy, shifting its previous focus on the western Pacific only to one that has added the Indian Ocean as well.4 Its enlarged naval presence in the Indian Ocean would sustain a new reverse-deterrence doctrine: when China’s SLOCs are under threat by a hostile Indo-Pacific blockade, the PLA-N would do likewise, mainly through submarine warfare until its carrier- based expeditionary fleets are ready for action.5 The BRI further requires military protection with another reverse design of the Mahanist idea of sea- power: commercial ships leading the way with warships behind.

The second question is whether the Quad will be further institutionalized and form the core of a mini-NATO in the Indo-Pacific.6 This is currently more of a trend forecast than a concrete alliance-building by the countries concerned. Yet the trend is more discernible with an Indo-Pacific evolution driven by a transition from Washington-Canberra-Tokyo trilateralism to the Quad in ad- dressing China’s rise that weakens US superiority. A strengthened collective defence architecture in response to China is deemed necessary that is as inclusionary as possible with like-minded participants. Although New Delhi has restricted the Australian Navy’s role in the Malabar Naval Exercises in the last two years, this paper anticipates that it is a matter of time that one way or another Australia will become a full participant in the exercises.

Gradually the Quad has potential to become an open-ended process of ex- pansion with more security partners to join the club. Basically the Quad is a new type of concert of powers glued together to cope with some commonly perceived security challenges. It is attractive to other regional like-minded stakeholders in the sense that Quad members are the top economies and can provide the public good in security-building in the Indo-Pacific region. At the same time, due to dichotomous vested interests among them and other potential members, the club will organically tend to be a lot looser than a real coalition in Asia. For instance, India is not an ally of the other three and it will require a sufficiently high return before it is willing to cooperate militarily with the others in a major confrontation, or alternatively, unless it perceives exter- nal threats that are serious enough for it to join the others in such an event.

Today the Indo-Pacific strategy is still controversial; controversial in a sense that one’s perception of it may be derived from where one is sitting. As a foreign policy tool Quad members entertain diversified views towards it, as testified by Indian Prime Minister Modi’s keynote speech in the 2018 Shangri-La Dialogue that pointedly downgraded the coalescing effects of the Indo-Pacific endeavor.7 Militarily, however, the bottom lines of the Quad members do converge. Behind-door defence cooperation against the targeted rivals is underway. Even if the Quad does not evolve into a fully- fledged multilateral military alliance, its features of an informal defence bloc stimulates further defence ties and arms build-up. The frequency of joint army-navy exercises among the Quad members has been increased. This is why the Chinese regard the Indo-Pacific strategy as a new geo-strategic challenge to all, as it may destabilize the already tense security situations in the two ocean regions.8

The third question is how Indo-Pacific countries strike a balance between America and China. The Indo-Pacific strategy may reduce the space for middle powers to maneuver in Sino-American rivalry. Given their dichoto- mous economic and security needs upon the two top powers, and testified by the Australian case, a right strategy is increasingly beyond reach. The Indo-Pacific strategy is itself a strategy of external balancing against China in the area of security, or an offset strategy in a potential form of containment. The Indo-Pacific partners find it hard to choose between hedging, balancing and ‘bandwagoning’. Sino-American tension has now created an off-bal- anced relationship for all middle powers in the region where a security guar- antor and a growth facilitator are in a constant duel. They have been caught in the cross-fire. To US allies, if they can strike the right balance, it means that their best interests would be served when they can ‘have their cake and eat it too’. Yet their alliance commitment and ideational preferences make this difficult to materialize. Therefore, their interaction with Beijing will al- ways be oriented by their relations with America, their strategic culture, and defence policies which emphasize a worst-case scenario. Unless they define their best national interests in their own way, rather than to serve someone else’s agenda, the off-balanced ties will continue indefinitely.9

The Land-Sea Nexus

The security challenges in the Indo-Pacific region are abundant. Asia’s four flash-points are all located in this area. They are worsening because all of them, originally as sovereignty disputes, have now been structured into the geo-strategic contention of the major powers. For instance, the South China Sea dispute is no longer just a disagreement on territorial demarcation among the claimants, but more subject to Sino-American rivalry over the shape of the world order.10 The same can be said of the Korean and Taiwan conflicts. Pakistani-Indian confrontation in Kashmir continues unabated and negatively affects Sino-Indian tensions. As a result, the management of the regional conflicts has become hijacked by global power politics, vividly shown by their emerging connection with the Quad, which may gradually render the existing regional conflicts more zero-sum and globalized. Thus the regional problems are more difficult to be contained with the relentless intervention of outside powers.

Exactly because this changing nature of the geopolitical environment is rooted in the territorial disputes in the Indo-Pacific region, the land-sea con- nection has become more visible and entrenched. Except for wars against terror, the region has seen no major land warfare since the end of the Cold War. As far as the PLA is concerned, direct infantry combat engagement will become a rare thing in the future. This underlines its grand naval expansion into the Indian Ocean and beyond. The dividends of the Soviet collapse are reflected by the fact that, for the first time in 300 years, China has been free from land invasion.11

Yet the maritime conflicts can also be triggers of major wars on the ground, seen from the following angles.

Firstly, with a pro-independence party in Taipei, the prospects of armed confrontation are on the rise with possible US involvement. Former Defense Secretary Carter and incumbent US officials openly called to incorporate Taipei into the Indo-Pacific camp and Taiwan responds positively to the call by re-adjusting its defence posture and increasing its military budget. Were there a war in the Taiwan Strait, likely in a form of amphibious operations, it is bound to be a substantial one.

Secondly, a number of Indo-Pacific states are not only troubled by the maritime sovereignty disputes but also exposed to continental confronta- tion since the maritime regions are geographically connected by the shared land borders, as is the case with China and Vietnam. While their maritime disputes most likely induce naval clashes, it is plausible that when these clashes escalate, their shared borders would become venues for land war- fare which would be more intensive than on the high seas. This chain reac- tion war scenario and planning underline the land-sea nexus in any future army build-up by all involved.12

Finally the SLOC safety has become a crux in linking land and sea in military terms. All East Asian nations are heavily dependent on the SLOCs in the In- dian Ocean for economic growth at home. This nexus of economic security and military security highlights not only the risks for conflict in this region, but also prohibits the application of either land force or naval power as a means of solving such conflicts. This dichotomy has the effect of manag- ing the potential for wars: on the one hand, their SLOC vulnerabilities make them cautious in the excessive utilisation of land forces for solving disputes; while on the other, if their SLOCs are cut-off, a spill-over effect in the form of land warfare can be anticipated. Most strategists now focus on the maritime challenges in evaluating the Indo-Pacific strategy but the continental chal- lenges are no smaller and can become dominant in certain circumstances, such as in the case of the Sino-Indian border confrontation in the Doklam re- gion in 2017. At least no maritime conflicts have so far been serious enough to cause a major naval conflict. On the other hand, while the infantry units were facing off in Doklam, the PLA-N staged a large naval drill in the Indian Ocean. Similarly the Indian Navy matched the Chinese actions, with support from America and Japan.

The Doklam Faceoff: a Practical Case of Land Power Application in the Indo-Pacific Connection

In June-August 2017 armed foot-soldiers from China and India confronted each other in the Doklam region near the Sino-Bhutanese-Indian border junction. This confrontation of 71 days moved both countries to a sub-state of war for the first time since the 1962 Sino-Indian border war and exceed- ing the Camp Confrontation of 22 days in 2013. To the great relief of many observers, the Indian troops returned to their territory and the Doklam bor- der region remained quiet again. Yet the consequences will be long felt as both armies will accelerate force re-deployment and deterrence in case such a confrontation occurs again.

The Standoff Assessed from a Strategic Height

The Doklam event marked the first time that Indian soldiers extended the border tensions from the disputed Line of Actual Control (LAC) to a demar- cated region.13 Indian and Western security interlocutors saw the Indian move in the light of stopping China’s road construction in the region that could pose a threat to the strategically important but vulnerable ‘Chicken’s Neck Passageway’ or Siliguri Corridor, [a small tract of land between Bangladesh in the south and Nepal, China and Bhutan in the north that connects eastern India with the main part of the country]. In fact the PLA’s project was a section of connection road used for logistical supply to the camps near the mountain ranges, not a main road to transport heavy military equipment, with the construction having been launched a few years ago.

Common sense would have one believe that this minor road work could not be an effective reason for the border crossing that disproportionally upset overall bilateral relations and which may have potentially led to a nuclear war, unless the act was the form of a tactical move to realize a strategic objective.14 Therefore, if one questions the motivation of this move, a two- layered answer can be explored from a Chinese perspective: a Sino-Indian bilateral one, and a geopolitical one.

Bilaterally there were many possible triggers for the Indian action. In the lead-up to the crisis, China and India were involved in a number of serious quarrels with some key sources of friction listed below:

- The Sino-Pakistani BRI infrastructure undertakings go through Kash- mir, a major reason for Modi to reject participation of Beijing’s BRI summit in May.15

- New Delhi heavily resented a Sino-Pakistani arrangement for the PLA to gain base access to the Indian Ocean.

- China repeatedly denied India’s application to enter the international Nuclear Material Supply Group.

- The PLA-N has made regular forays into the Indian Ocean. This rep- resents a new normal which annoys the Indians who carefully guard against foreign activities there.

The Indian Army’s unexpected Doklam move may have indicated a burst of anger by Indian leaders who smartly took advantage of China’s unfavorable relations with a number of key powers in the region and beyond. The wors- ening Sino-American relations have, in particular, emboldened New Delhi to believe that the crossing could be mounted without serious consequences. The rise of India has substantially changed the past pattern of the trilateral interaction, in which the US and China16 would treat India as an inconse- quential player. Now its weight in the triangular arrangement has increased significantly when Sino-American rivalry reaches a new height, even if it is still a power far behind the US and China. India is strategically situated in the Indian Ocean where the critical SLOC choke points make Chinese shipping vulnerable. The Indian Navy’s strengthening of base reconstruction in the Indian Ocean and the PLA-N’s gradual westward moves have generated action/reaction dynamics that impact on their land border tensions. Indeed India’s maritime and continental stance vis-à-vis China is particularly valued and grants it a pivotal position in the Quad.

A New Pattern of Coordinated Military Balancing vis-à-vis China

Geo-strategically, this ‘minor land warfare’ had effects far beyond the Doklam region itself. Rory Medcalf proposed that India’s Doklam action could create a pattern of resistance to China’s assertive approach to sover- eignty issues elsewhere, especially in Asia’s maritime domains.17 The under- lining tone of this proposition is to use proactive military balancing against China’s increased reach in the Indo-Pacific region.

More importantly, India’s Doklam move could be the first test of a series of collective efforts that link the disputes of the South China Sea, East China Sea and the Taiwan Strait to challenge China’s sovereignty positions. In a land-sea linkage this collectivity may have pointed to an emerging phenom- enon where a dispute against China in the East is pursued with collaboration of like-minded countries in the West, and a land border conflict with China triggers a chain of matching actions in the maritime domains by its allies/ partners. This evolution of collective moves to offset the PLA’s expanding range of power projection reveals how the territorial disputes have been structured into the global major power rivalry and Asian geopolitics. Here it is interesting to point out that India’s Doklam action was taken shortly after Modi’s visit to the United States. A conspiracy theory could be conveniently contemplated. At the time of the standoff there was a short, but intense, Sino-Vietnamese quarrel over Vietnam’s exploration of oil resources in the South China Sea, forcing the Chinese defence chief to abandon a planned visit to Hanoi. The invisible intervention of extra-regional powers will become more visible under the Indo-Pacific strategy.

The Consequences of Doklam

The peaceful ending of the Doklam confrontation was anticipated all along, as no one in Beijing and New Delhi intended a war to resolve the standoff in the first place. The Indian soldiers crossed the borderline with muzzles point- ing to the ground, expressing a clear message that ‘we are not here for ac- tion’. However, the Chinese see the other side of the event: the Indian Army came into the Chinese territories for over two months. Although the Indians eventually withdrew first, and the PLA soldiers stayed where they were to continue the road works until the snowy season, India’s action cast humili- ation on China and it got away with this. Beijing may retaliate against this intrusion in other ways on a long-term basis, for example, by providing more military assistance to Pakistan. It may deny India’s bid for a UNSC perma- nent seat more firmly in the future and coalesce with the Indian Ocean Rim states more pro-actively.18 The PLA-N has mounted more frequent entries into the Indian Ocean and enhanced its penetration in South Asia.

On the other hand, Beijing and New Delhi are clear that it is in both coun- tries’ best interests that they are not adversaries. The Xi-Modi Wuhan Sum- mit in May 2018 re-set the bilateral relations in a positive direction, which led Modi to stress Sino-Indian cooperation in this year’s Shangri-La dialogue.

It was music to the ears that he defined the Indo-Pacific advocacy as a geographical concept, not a strategy, and that it is open to all interested in joining. However, the Doklam event reminds people of the hidden fact that the Indians employ the Quad strategy and military cooperation as a practical counter-measure vis-à-vis China.

The Parallel Efforts to Enhance Land Power and Sea Power

The lingering war prospects in the Himalaya region and the new venue of Sino-Indian rivalry in the Indian Ocean underline the changes in Asia’s geo-strategic landscape. These will oblige the Chinese and Indian armies to readjust their overall defence posture in both the continental and maritime regions. Both of them have long contemplated a Sino-Indian land clash in the context of a simultaneous battle in another strategic direction. For the PLA this is the east flank, namely the maritime domains. A war in the Taiwan Strait may have the Indians tempted to make a move in Himalaya, like in 1951 when India occupied Tawang as the Chinese fought in Korea. For the Indian Army it has always faced potential conflict in two regions: with China in the north-west and Pakistan in the north-east. The close military coopera- tion between the Chinese and Pakistani armies puts enormous pressure on the Indian Army in war planning. It was not coincidental that when the PLA and the Indian Army confronted each other in the Doklam region in July 2017, the Indian-Pakistani clashes in Kashmir briefly reached a high point.

The PLA-A’s New Force Posturing

At the beginning of the 21st Century the PLA initiated a debate on how to meet the challenge of multiple and simultaneous military threats, a repeat of history of the late Qing dynasty when officials debated whether to prioritize coastal defence against western maritime invasions or against continental threats from Russia’s penetration into Xinjiang.19 Indeed China has never faced less than two major military threats around its periphery since 1949. From time to time these threats can be severe. In the contemporary debate Beijing has identified the maritime challenges as the primary potential cause for war involving China and the potential for land warfare secondary. This strategic calculus led to the adoption of a 1.5 war doctrine: a full war in the oceanic direction and a 0.5 war in the continental direction. The former is of- fensive- defence by nature, aiming at securing maritime interests, especially China’s sovereignty claims in the East and South China Seas. The latter is defensive-defence, taking advantage of the high elevation of the Himalaya which favors defence over offence. Such a doctrine suits China’s overall national defence strategy focusing on handling any naval-army warfare in the Taiwan Strait.20

When this doctrine is translated into force and weapons deployment, an ‘east-heavy’ and ‘west-light’ pattern of posturing can be discerned. Until recently no single PLA Group Army (a Group Army usually consists of up to 12 brigades supported by enabling brigades – Ed.) was deployed in China’s western regions, if one folds the Chinese map in the middle. In Tibet only three lightly-equipped field brigades are currently deployed and only four di- visions in Xinjiang, which deals with the Central Asia region as well. And the PLA force deployment along the Sino-Indian border is ‘light in the frontline and heavy in the rear’, partly due to the geographic features of the moun- tainous ranges and partly due to the extraordinary cost of frontier defence in high elevations; it is seven times more expensive to deploy a foot-soldier in Tibet than in the inland provinces.21

Today the US-centric Indo-Pacific combat posture may have heightened military pressure on China’s Theatre Command – West*. As the Doklam standoff testified, a scaled land war with India is not unimaginable, nor contingent on a naval clash in the east or in the Indian Ocean. Furthermore, an armed confrontation can happen not only in the LAC regions but also in undisputed areas along the shared border. This prospect of a continental war dismisses the PLA belief that no-one really wants to fight a land war with China. More strategically, it indicates that the current trend in the PLA to belittle the role of the army in future joint warfare is premature. After all, China is historically and strategically a continental country, even though its maritime regions now contribute more to its well-being. Logically the need to upgrade the 0.5 war scenario to a full one can be seen by its own right. Then the PLA-A has to enhance its western troops independent of the con- siderations of the eastern flank.

However it may take a long time for the PLA-Army (PLA-A) to realise this pivot to the west, as it can be a very expensive enterprise in both financial and human resources that impacts upon war preparation in the maritime domain. The PLA-A has begun to address the loopholes of its unbalanced troop deployment since 2017. Primarily the PLA may have realised that the ‘light deployment in the frontline but heavy in the rear’ disposition of its forces created a significant manpower imbalance with the Indian Army. Cur- rently the gap is about five to one in favour of India, which may, in turn, have served as a cause for India’s bold action in Doklam in 2017. Inevitably this pattern of deployment has to be readjusted, with troop enhancement and battlefield force posturing in the forward areas of Theatre Command - West. For instance, the headquarters of the 76th Group Army has been re-de- ployed to Xining from Baoji in the on-going army restructuring. This substan- tially reduces the response time and logistic support lines to border troops. The ground force in Tibet has been strengthened with more manpower in the aftermath of the Doklam standoff.

In the meantime, the PLA has re-oriented its Indo-Pacific strategy to high- light the expeditionary nature of PLA-N transformation. Not challenging India’s special interests in the Indian Ocean, PLA analysts believe that India needs to be aware that areas around Gwadar, Chittagong, Hambantota and Sittwe have not been India’s sphere of influence. PLA-N footprints (not footholds) would be gradually created. The PLA has a long-term goal of acquiring overseas logistical points to supply its naval expeditionary fleets to get to the Indian Ocean and the South Pacific, although there is no plan for immediate combat deployment. On the other hand, this gradual naval expansion in the Indo-Pacific region is now more closely projected with con- tinental war scenarios in terms of budgetary distribution, troop allocation and weapons research and development programs. The Sino-Indian connection is particularly prominent in this nexus. The PLA’s ultimate goal is to acquire army and naval capabilities that can be jointly applied in supporting each of the land and maritime strategic directions.

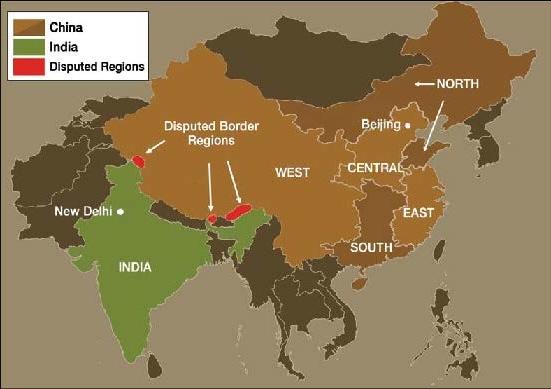

Figure 33. China and its Theatre Commands. Note the disputed border regions in TC West with the Doklam region being in the middle near Bhutan. (Image: Major Conway Bown)

The Army’s Force Transformation

The PLA-A has also made great efforts to improve the weapons systems in the Tibetan/Xinjiang provinces, which are generally obsolete compared with those in other theatre commands. Land warfare on the plateau partly dictates that mountain troops are lightly-equipped. This is particularly true to both the Indian and Chinese armies located in these areas of extreme weather and geographic conditions. For the PLA-A its missions along the Sino-Indian borders are exclusively defensive by way of defending mountain passes and ranges. The current efforts to strengthen their capabilities are to equip them with better light weapons that enhance firepower and mo- bility.22 Among the new equipment the PLA-A troops in Tibet now receive are 32-ton wheeled tanks that can easily traverse mountainous regions; the CS/VP4 Shanmao ‘Lynx’ all-terrain vehicle that can tow 122mm guns to places above 4,000 metres; PCL-09 122mm truck-mounted (self-propelled) howitzers; PHL-03 300mm multiple-launch rocket systems and the Type 89 .50 calibre machine-gun with a weight of 26 kg, the lightest of its kind in the world.

However, the emphasis has been placed on creating a new integrated force in the PLA-A that is capable of fighting in complex electromagnetic condi- tions and with other services—such as the air force and the missile force—in conducting informatised joint operations. This requires sophisticated C4ISR (command, control, communications, computer, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance) command structures, tactical data-link systems within the army and with other services and an effective logistics supply network. For instance, PHL-03 300mm rocket launchers have a range of 300 km with terminal guidance with the support of the Beidou satellites. They would be deployed a relatively long distance from the front line. In tactical terms, when a conflict erupts, the PLA-A, as the defensive side, would use them to strike the enemy’s second echelon in a pin-point manner and prevent reserve troops from reaching the front line as a supporting force. At the height of the Doklam confrontation, the PLA-A transferred PHL-03 units from 73rd Group Army in Fujian to Tibet to ready them for this purpose. They are actually tasked with this role in the Taiwan Strait and this transfer shows how close the two armies were to clashing. More strategically, this crystallizes the PLA- A’s overall transformation: all advanced campaign units should be able to at- tain the capability of ‘reaching all battle zones’ within the national boundary and beyond, quickly and amid the enemy’s strike capability. In August 2018, units of the 77th and 83rd Group Armies conducted combat drills in Tibet.23

The biggest challenge to the PLA-A is to achieve reliable logistical supply in the plateau regions when sizeable ground combat operations are launched. In 1962 poor logistical conditions forced the PLA-A to retreat. In this case, battlefield victory was based on unsustainable human logistics. It proved the saying that in high altitude land warfare – ‘reach is half the victory’. This painful lesson has served as the starting point for the PLA-A to plan future applications of force, not only along the Sino-Indian borders, Sino-North Korean borders and across the Taiwan Strait, but also for other combat sce- narios, including the PLA-A’s peace-keeping operations in Africa. ‘Amateurs talk about strategy but professionals talk about logistics’ underscores the PLA’s efforts to construct a modern logistics system through preferential investment and civil-military integration. This also explains why the PLA-A makes it a priority to build infrastructure, such as roads and airports, in the plateaus in Tibet and Xinjiang for the future application of force. Other land warfare considerations for this type of scenario include the following:

- Creating a modern force of strategic airlift, employing the PLA’s C-17 -like strategic transport Y-20s for use in both future continental and maritime warfare. In peacetime this saves the cost of the forward-de- ployment of troops but allows, in times of conflict, the transportation of troops and equipment to the battlefield rapidly. Eventually a fleet of 300-400 Y-20s will be inducted.

- Creating a large force of unmanned aviation vehicles. UAVs are the most cost-effective equipment for land warfare in areas not easily ac- cessible to army units. The PLA-A is developing and inducting no less than a dozen types of UAVs. Simultaneously, research is being con- ducted on the best types of weapons to arm them and the optimum type of batteries to boost their combat suitability and sustainability in mountainous and amphibious operations.

- Helicopters are also crucial for the PLA to improve logistical supply, medical support and troop transportation in future land warfare. In the plateau areas airmobility is critical for the type of operations anticipat- ed. Currently the PLA-A is using a number of combat helicopters to assist in mountain warfare, as well as likely combat operations in the maritime domain. When China’s Z-20, an equivalent to the US UH-60 Blackhawk, enters service in both transport and strike versions in a few years, the PLA-A’s battlefield efficiency will be improved.

Army Building for the Indian-Pacific War Scenarios

The Indian-Pacific strategy has broadened the visions and scope of army transformation in the Indo-Pacific region. The land and ocean nexus has never been so influential on the countries in the area. The changing Indo- Pacific security landscape will impact on most of the states in South and East Asia when outside powers intervene vigorously. However, the maritime focus in the Indo-Pacific strategy is more emphasized than the continental one, although the latter gains currency in the new land-maritime game, and it is likely that any land war among the major powers would be larger in scale in terms of human casualties and material destruction.

The Indian Efforts

The preparation for land warfare is probably more important to India than to other states in the Indo-Pacific region, when the Indian Ocean remains quiet under separate US and Indian control. This would help set the immediate and long-term objective for the Indian Army to transform itself to become a joint force.24 Specifically the primary driver for this transformation is to shift India’s sequence in war preparation from Pakistan-focused to China-fo- cused. This is a strategic move involving tremendous human and resources relocation. On the land front the Indian Army will create another army corps for offensive operations in addition to its 12 divisions/brigades already deployed along the Sino-Indian border. In the meantime the Indian Army will adjust its combat posture compared to that of the PLA-A. While it maintains its front-heavy deployment, it will further enlarge the strategic depth with more troops stationed in the rear.

At the same time the Indian Army will, like the Chinese Army, strengthen the defence infrastructure in the three sections of Sino-Indian border. New airports, roads, forward logistical storages and other facilities will have prior- ity in construction for the purpose of moving troops to the front line quickly. New weapon systems that suit mountain warfare will also be continuously introduced. The strategic objective for this force posturing is to maintain human and material superiority over the Chinese military across the border. On the other hand it is hard for the Indian Army to keep a five to one ratio in manpower superiority against the PLA-A. In terms of the quality of weapons there will gradually emerge a generational gap between the two armies in favour of China, even though the Indian Army buys first rate weapons from the international market.

The army modernization will be pursued in the context of potential Sino-Indi- an encounters in the Indian Ocean where the Indian Navy has strengthened its presence and capabilities. This is the defence component of the Act East policy with a focus on the Malacca Strait in times of conflict with China, most likely along the land borders. The Andaman and Nicobar Command—the first and only tri-service command with the best location for the Indo-Pacific region—is tasked with such a mission. Will India hypothetically fulfil its obli- gation of blockading the Chinese SLOCs in the Indian Ocean? It depends on if there is a major Sino-Indian armed clash in the Himalaya plateau, and the level of Chinese Indian Ocean expansion in the long term. Clearly the Indian Navy has specific war scenarios in countering the PLA-N’s moves into the Indian Ocean region.25 For instance, anti-submarine warfare ranks high in its war planning and in its joint war drills with outside powers, such as the US and Japan. This is a realistic type of war preparation. It will take a long time for the PLA’s major surface combatants (aircraft carrier battle groups) to be action-ready in the Indian Ocean but submarines are relatively easy to pen- etrate into this potential battle area if the PLA-N acquires a sufficient number of nuclear attack submarines in due course.

Other Concerned Armies in the Indo-Pacific Theatre

Most Quad states and their partners are maritime powers. This means that they would value maritime stability as a primary goal in their key national interests. Therefore the land connection is comparably thin in their Indo- Pacific reasoning. Yet the land dimensions in their war preparations and overall force transformation are clearly important at a time of great change in the international and regional order. The army is the service with more manpower and influence in most Indo-Pacific countries and assumes more of the onus in fulfilling the military’s dual missions of guarding against foreign invasion and keeping domestic stability in order.

The US Army bears the first brunt in re-shaping the Indo-Pacific military or- der. The renaming of the US Pacific Command as the US Indo-Pacific Com- mand (INDOPACOM) reflects its enlarged responsibilities. [See map that accompanies General Brown’s speech - Ed.] For instance, the command of INDOPACOM now covers the east coast of Africa through the Indian Ocean. The name change may also indicate its mission priorities in meeting China’s long-term challenge, remarked by US Admiral Harris – the outgoing commander of Pacific Command – in the renaming ceremony. In the short term, the South China Sea would be the focus with persistent US naval entries into the 12 nautical mile zone surrounding Chinese holdings there.26 Over time the Indian Ocean would be another key venue for Sino-American encounters. It is not by accident that the coverage of INDOPACOM just overlaps that of China’s BRI.

Under Trump, the US’ Indo-Pacific pivot will continuously accelerate with increased budget and capabilities. Here the army is a critical player in joint operations with the navy and air force in any potential application of US mili- tary power. From the Korean Peninsula to South East Asia and to the Indian Ocean the US Army is the dominant power and is behind all potential land and maritime clashes between China and its neighbours. The big question is whether this dominance will be oriented into a containment of China. This will have a profound impact on Indo-Pacific security.27

Japan is under both constitutional constraints in projecting force presence overseas and under pressure to enhance its defence capabilities and allied cooperation to cope with the new international changes. Quad may be an effective offset to the threat perceived, as its collective nature helps Japan to re-position itself in the future security architecture in the Indo-Pacific region. But on the whole it is because of Japan’s territorial disputes with its neigh- bors that the security arrangement of the Quad is being valued. Technically, building a strong amphibious force is essential against the background of its maritime disputes with China, Korea and Russia. The Japanese Army is shifting its defence gravity from the north to the south in the sea-land nexus. The Japanese ground force will increase its reach beyond the national borders in terms of peace-keeping or participation of multinational military exercises with its Indo-Pacific allies and partners.

The Australian ground force is doing similar things. Currently the Austra- lian Army is still carrying out combat missions in a number of countries. It will continue to be part of the international war on terror and serves as the security guarantee for peace and stability in the South Pacific. Its broad- ened presence in Asia is one of the drivers for its transformation, including revisions in combat doctrines and force posturing. One such evolution is the army’s efforts to strengthen its special-operations task force and its overseas projection of power integrated with Australia’s annual Indo-Pacific Endeavour exercise. At a more strategic level, the Australian Army will plan its Indo-Pacific posture and combat actions within the land-sea nexus, in particular under the US-Australia defence cooperation, through [the] full implementation of Australia-US force posture initiatives. The US Marines rotation in Darwin will be fully implemented soon, and Canberra will seek to strengthen multilateral security partnerships with like-minded nations in the Indo-Pacific region through joint training and exercise opportunities.

The Brief Summary

What has been discussed in this paper is more or less a trend analysis, not a reality check in its empirical sense. Quad is in its embryo stage of de- velopment. There is a large question of how far it can go, as the countries embrace diversified objectives in joining it. None of the members will be willing to fight for another unless this aligns with its own national interests. If a common perception of China’s rise is the foundation, Beijing will be aware of the effects in bringing them together against its own international stand- ing and interests. It is unlikely that China will annoy all of them to the point of turning them against it in a cohesive and collective way. The improved Sino- Indian relations after the Xi-Mudi Wuhan Summit in May, and the improved Sino-Japanese relations prior to Xi’s state visit to Japan, may have removed an immediate trigger for the dual bilateral relations to worsen, and thus may slow down the Quad reconstruction.

There are more challenges for the Indo-Pacific strategy to materialize. So far there have been no collective Quad plans for Indo-Pacific economic or defence cooperation. A NATO Article 5-type of organizational buildup is out of question. Even with a common threat perception of China and Russia, each nation’s stake, and its resultant reaction, are quite different and will remain so for a long time to come. Budgetary constraints are enormous and have already delayed a US military pivot to Asia; slowed India’s Army enhancement vis-à-vis the PLA-A; reduced the Australian Army’s further commitment to engage Indo-Pacific states; and restricted Japan’s military reach beyond its national borders. As far as the army sector is concerned, it will probably play a comparatively smaller role in the Indo-Pacific security- building because, after all, the region is overwhelmingly maritime. Unless land border disputes evolve into major armed confrontation between ground forces, oceanic concerns will preoccupy political and military leaders.

Figure 34. While border incursions and standoffs continue to raise tensions, Indian Army soldiers recently trained with soldiers of the PLA-A in counterterrorism techniques. (Image source: Unknown)

Figure 35. A soldier from 3rd Brigade launches a PD-100 Black Hornet Nano unmanned aerial vehicle. The Black Hornet is a simple UAS able to provide short-range reconnaissance and is virtually undetectable when flying a mere 10 metres above the enemy. (Image: DoD)

Endnotes

- Rory Medcalf, “A Term Whose Time Has Come: The Indo-Pacific” The Diplomat, 4 December 2012, Rory Medcalf, Pivoting the map: Australia’s Indo-Pacific System, Strategic and Defence Studies Centre, Australian National University, Canberra, 2012

- See, for instance, U.S. National Security Strategy and National Defense Strategy, Washington D.C., November 2017.

- Krepinevich, Andrew, Why AirSea Battle, Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessment, 2010.

- The Strategic Research Department 2013, The Science of Military Strategy, the PLA Academy of Military Science Press, p. 106.

- You Ji, China’s Military Transformation: Politics and War Preparation, Cambridge: The Polity Press, 2015.

- General Brown, Chief of the Army, U.S. Indo-Pacific Command endorsed the use of the words Mini-NATO in his speech to the Australian Army Chief Symposium, 6 September 2018.

- Prime Minister Modi’s keynote speech in the 2018 Shangri-La Dialogue, Singapore, 2 June 2018.

- Chengxin Pan, “The ‘Indo-Pacific’ and geopolitical anxieties about China’s rise in the Asian regional order”, Australian Journal of International Affairs, Vol. 68, No.4, 2014

- Hugh White, The China Choice - Why We Should Share Power, Canberra, 2013.

- You Ji, “Sino-US “Cat-and-Mouse” Game Concerning Freedom of Navigation and Overflight”, Journal of Strategic Studies, Vol. 39, No. 5-6, 2016.

- Qiao Qingchen, “The strategic issues concerning China’s air defense strategy under the informatized conditions”, Military Art Journal, No. 3, 2003, p. 43.

- Zhang Youxia, “Four changes in the campaign theory in joint land border operations in a chain-reaction war”, Military Art, No. 2, 2002, p. 23.

- Indian Times, 13 January 2018; and China News Live, Phoenix TV, 15 January 2018

- Peter Hartcher, “The China-India clash that could lead to nuclear war”, The Sydney Morning Herald, 25 July 2017.

- Inaya Kalim, “China Pakistan Economic Corridor – A Geoeconomic Masterstroke of China”, A Research Journal of South Asian Studies, Vol. 32, No. 2, 2017, pp.461-475

- Harry Harding, “The evolution of the strategic triangle: China, India and the US’, in Francine Frankel and Harry Harding (eds.), The China-India Relations: What the US Needs to Know, Columbia University Press, 2004, p. 323.

- Rory Medcalf, “Who Won?”, The Interpreter, The Lowy Institute of International Affairs, 31 August 2017.

- Editorial “Countries in South Asia have rights to develop cooperative ties with all major powers”, The Global Times, 17 August 2017, p. 14.

- Li Yuanpeng, “A Debate on Coastal Defense or Fort Defence in Strategic Focus in the Late Qing Dynasty”, China Military Science, no. 2, 2002, p. 57.

- You Ji, “Indian Ocean: a Potential New Zone for Grand Sino-Indian Check-game”, in David Brewster (ed.), China and India at Sea: Competition for Dominance in the Indian Ocean, The Oxford University Press, 2017.

- Xu Yan’s comments in the TV Documentary The Sino-Indian War in 1962.

- Xia Guofu “The combat methods for the GAs in cold high plateau under the conditions of a chain-reaction war”, Military Art, No. 8, 2002, p. 53.

- The National Defense Program of the Voice of China, 4 August 2018.

- Vijai Singh Rana, “Enhancing Jointness in Indian Armed Forces: Case for United Commands”, Journal of Defense Studies, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2015, pp. 33-62.

- David Brewster (ed.), China and India at Sea: Competition for Dominance in the Indian Ocean, The Oxford University Press, 2017.

- You Ji, “Sino-US “Cat-and-Mouse” Game Concerning Freedom of Navigation and Overflight”, Journal of Strategic Studies, Vol. 39, No. 5-6, 2016.

- Michael Swaine,“A Counterproductive Cold War With China: Washington’s “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” Strategy Will Make Asia Less Open and Less Free”, Foreign Affairs, March 2018.

- Japanese Defense White Paper 2018, Tokyo, 15 August 2017.