Mr Michael Shoebridge

Director of Defence and Strategy, Australian Strategic Policy Institute

‘Thanks for the opportunity to talk to you this afternoon. I’m Michael Shoebridge, Director of Defence and Strategy at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute.

‘What I’m going to cover in 30 minutes is first the idea of the Indo-Pacific, then some key global challenges relevant to the national security communities in each of our regional nations. And lastly I’ll say a little about how these challenges might be approached in the Indo-Pacific in ways I hope make sense to the assembled Chiefs of Army and subject matter experts assembled here.

‘The views I’ll give today are mine, not an ‘ASPI line’, as ASPI’s approach is to allow our different people to hold different views.

‘Before I get into the presentation, I thought I’d make observations about the relevance of land forces to a region whose map is dominated by sea.

‘A simple capability observation is that control over large parts of the sea and trade routes can be exerted from land as part of an integrated air, sea, land, cyber and space force.

‘In our region, there’s also the historical fact that land forces have dominated a number of Indo-Pacific states’ militaries, because of these states’ focus on internal security and nation building.

‘First, what is the Indo-Pacific? What is being connected? Why does it matter?

‘The Indo-Pacific is a term that provides a way of thinking about our region that seems useful in understanding events and trends. It is starting to replace the term Asia-Pacific, mainly because the connections across the broader Indo-Pacific are more obvious than they were even as short a time as a decade ago.

‘The Indo-Pacific concept started to be used formally in Australia at the time of the 2013 Defence White Paper, after being raised in the think-tank world—notably by Rory Medcalf, then at the Lowy Institute, and now head of Australia’s National Security College. It was a contested term then, much more than now, as people had invested a lot of intellectual effort and careers into the idea of the Asia-Pacific.

‘In the US in particular, the Asia-Pacific made particular sense in the Pentagon because there was a nice clean boundary between PACOM (US Pacific Command) and CENTCOM (US Central Command), and India was not within PACOM’s area of responsibility. The bigger background there, of course, are the obvious physical and economic facts––like California with an economy the size of a G-20 economy being on the Pacific coast. This ensures that any big US strategic concept will have ‘Pacific’ in it.

‘In China, the idea of the Asia-Pacific continues to be appealing, maybe because from China’s perspective it is what China sees looking out from its location on the Asian landmass.

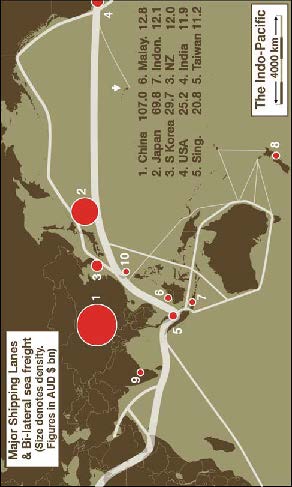

‘In Australia though, starting in the early 2010s and accelerating in recent years, the Indo-Pacific concept makes sense. In the most pragmatic way, this is shown by a single image—a map that appeared in the 2013 Defence White Paper and has been used in other documents since—including the Government’s 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper.

‘While as a rule I don’t use Powerpoint in presentations, today I’ve made an exception to be able to show you this map—because I think that it conveys some big ideas very clearly and so can be a supporting prop for my remarks.

Figure 12. Major shipping lanes in the Indo-Pacific (Image [derivative]: Major Conway Bown)

‘Turning to it now, you can see the biggest feature on it is the set of lines and tracks shading from yellow to orange to bright red. They are not ‘sea lanes’ as you usually see them, but the actual tracks of thousands of ships mapped and plotted onto the map. The density of the ship traffic is lightest when it is light yellow and most dense when it is bright red.

‘As you can see, the bright red line is deepest coming out of the Middle East, around the base of India and Sri Lanka, up through the Malacca Straits into North Asia. This is like an umbilical cord connecting Asia into Europe through the Pacific and Indian oceans. There are intense red bands within North Asia and between North Asian and South East Asian states.

‘Looking across the Pacific, you can see a bright red track at the top of the Pacific across to the US, but even more noticeable is the wide band of yellow covering the Pacific between Asia and the US.

‘What I think we can draw from this set of patterns is that these shipping traffic densities are a proxy for connections and interdependencies. They show the Indo-Pacific as a system of flows and interdependencies, mainly from an economic perspective.

‘The patterns show the deep interdependencies within Asia (North and South East), but also across the top of the Indian Ocean and between the US and the Asian landmass.

‘This is globalisation in action, with all the opportunities, risks and interdependencies that it brings.

‘But there’s another perspective here also. Unlike the Asia-Pacific, where the focus is on North Asia, this Indo-Pacific concept puts another part of the region in a central position—South East Asia. South East Asia turns out to be a set of nations which have intense connections with all other parts of the Indo-Pacific and within South East Asia itself.

‘But South East Asia is also located so centrally that it sits across a small set of bottle necks around the most intense trade flows (the Malacca Straits being an obvious example).

‘I’ll end this section with a quote from the 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper, which defines the ‘Indo-Pacific’ as the region ranging from the eastern Indian Ocean to the Pacific Ocean connected by South East Asia, including India, North Asia and the United States. So, the Indo-Pacific is not the entirety of the Indian and Pacific Ocean littorals, but is bounded and defined by the trade flow connections.

‘Now to move on to some national security trends that affect all of us in the Indo-Pacific and that we will need to deal with together in coming decades. I’ve selected eight that I’ll scamper through quickly.

‘While I do so, I’d like you to keep the ‘strategic geography’ of the Indo- Pacific in mind./

Global Population Growth.

Global population growth is driving a lot of change, particularly when combined with rising standards of living across Asia (the world has over 7.6 billion people now in 2018, [growing] from 1.5 billion to 6.1 billion over the 20th Century).

‘Last year, the UN reported that the current world population of 7.6 billion was expected to reach 8.6 billion in 2030, 9.8 billion in 2050 and 11.2 billion in 2100. Demand for food, services, manufactured goods from this larger, richer world population is straining food production systems, depleting ocean reserves, causing pollution and environmental damage to global ecosystems.

‘Population debates are happening in many parts of the world—Japan, Singapore and several European countries being examples.

Global Demographics.

Global demographics are changing different societies and economies in particular ways. This divergence will increase in coming decades. The broad features are an ageing North Asia and Europe, a young Africa and Middle East, and a mix of ageing with growing and young populations in South East Asia, the US and Australia.

Growing Mass Urbanisation.

With an increasing number of megacities routinely located in coastal regions, Growing mass urbanisation will create the conditions for large scale natural and human disaster recovery demands. Many of the world’s biggest cities are getting bigger still. The number of megacities—urban areas with better than ten million people—increased to 37 in 2017. Most of the world’s mega cities are in the Indo-Pacific.

Climate Change.

On top of the demands of the growing global human population, climate change is changing the patterns and extent of arable land. It is also causing a rise in extreme weather events that can cause large-scale natural disasters. Not new news for anyone living in or looking at the South Pacific.

Mass People Movements.

Mass people movements internationally, local conflicts and internal security tensions are all likely symptoms from the combination of these global trends.

‘These five challenges are regional ones, but they are also internal challenges for each nation, from the smallest Pacific or Indian Ocean island state to major strategic and economic powers like China, Japan, India and the United States.

‘Some states will necessarily need to devote considerable time and effort to managing their internal challenges—for example, the challenges China faces from its rapidly ageing population and the environmental consequences of its rapid economic growth, or the Mekong states’ challenges while benefitting from hydro-power but managing the human, security and ecosystem effects of that development.

The Information Explosion.

Humans can store and access more data more quickly than ever before. Humans are also creating and collecting more data than ever before. We are ‘...at the very beginning of the age of big data. Consider that 90% of the data that’s now out there about us has been collected in just the last two years. Last year alone, more personal data was harvested than in the previous 5 000 years of human history.’*

Technological Change.

Technologies are undercutting and empowering different parts of economies and societies. Data analysis is disrupting more fields of endeavour, whether [they be]:

- financial systems, through high speed trading or crypto currencies,

- taxi drivers, through Uber and Ola,

- booksellers, through Amazon and Apple,

- traditional stores, through Alibaba, Amazon and Tencent,

- global communications, through next generation technologies,

- supermarkets, through Amazon,

- advertising [agencies], through Google, Facebook, Alibaba and Baidu,

- media organisations, through online journalism and social media content creation, and

- government revenue systems, through the hard-to-attribute profit and revenue flows of online commerce.

‘This change has just started. Medicine, government and warfare are all likely to be transformed by this data-driven technological change. The speed of change is obviously outpacing not just policy and regulation, but Government leaders’ and officials’ abilities to comprehend the rapidly emerging elements.

‘The eighth and last big global trend we all know about, but which is still important to note, is the shifting balance of strategic and economic gravity into Asia—to North Asia, but also South East Asia, which was based both on the foundations laid after the Asian Financial Crisis and the ‘peaceful rise’ era of China under Deng Xiaoping.

‘That ‘peaceful rise’ approach combined with many countries’ adoption of engagement with China under the Bob Zoellick concept of China as a responsible stakeholder that would continue to liberalise and open over time.

‘This drove massive foreign investment inflows to China, technology transfers and supply chain relocations into China. Raw material exports to China from Australia, Brazil, the Middle East and Africa also featured (and continue).

‘It’s worth remembering the economic significance of South East Asia, notably, the fact that this zone of both prosperity and potential has some 600 million people along with habits of cooperation and integration.

‘India, as another example, is experiencing high year-on-year growth in its GDP, with much further potential because of its favourable demographics and resilient democracy.

‘While I’m saying economic gravity has moved towards Asia, it’s critical to remember that this is because of Asia’s rising prosperity.

‘At the same time though, the levels of prosperity in the EU, North America, Australia and the UK remain unique in human history. They remain societies of enormous capability, prosperity and innovation.

‘The point here is Asia’s economic rise is not being accompanied by the economic decline of ‘the West’.

‘The decrease in relative power is often lazily called ‘decline’. If the Romans had had this kind of ‘decline’, we’d still be living in a world with Roman emperors and Roman legions.

‘The Zoellick (Bob Zoellick was Deputy Secretary of State under George W Bush 2005-2006) ‘responsible stakeholder’ framework let everyone engage despite different strategic interests and values, while working to ‘socialise’ the Chinese Government and economy into the global order.

‘There was some idea that China would want some—but limited—changes to this global order and global institutions, but it was really all about China being incorporated into that system and being changed as this occurred.

‘These global trends may be old news, but their implications are still pretty far-reaching.

‘Thinking of the Indo-Pacific, these trends resulted in rapid military modernisation across Asia—giving nations that have been internally focused the ability to reach out and touch each other against the backdrop of latent historical territorial and sovereignty disputes in a region with weak regional security institutions—ASEAN and all its children—the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF), the ASEAN Defence Ministers Meeting Plus (ASEAN DMM+) et cetera.

‘New news though, is the return of the state actor to international security.

‘Let’s remember that since September 2001, counter-terrorism has been an abiding priority for many governments and remains an enduring challenge.

‘While many governments and policy thinkers were focused on counter- terrorism and globalisation since 2001, some analysts and strategic thinkers were noticing a return of state-focused national security was brewing.

‘Russia’s sense of anger, grievance and humiliation over the loss of its empire, its status and much of its power was causing a reaction. NATO’s expansion towards Russia combined with economic disaster for Russia in the 1990s—with GDP contraction of some 40%, which set the conditions for a resurgence of Russian nationalism.

‘The Russian state, under Vladimir Putin, used energy sales to reinvest in ‘malign silos of excellence’:nuclear weapons, Russian intelligence agencies, cyber technologies (state and non-state), a re-equipped, rapidly deployable military and, of course, a hybrid style of ‘lawfare’, disruption and warfare.

‘He did this despite his people’s clear needs for national investment in healthcare (to combat alcoholism and deal with an ageing population), pensions, infrastructure and education.

‘Iran proceeded to build proxy forces like Hezbollah, and later to pursue nuclear weapons technologies.

‘The DPRK continued to pursue security through nuclear weapons and missiles, while calibrating aggression and negotiations to get the benefits of international food aid and avoid the worst effects of isolation.

‘China’s ‘peaceful rise’ era under Deng Xiaoping is over. And we are now seeing the Chinese state start to show how it intends to use its growing economic and military power in the world—in ways that are disturbing other states and powers.

‘There is a dawning realisation that the [nature] of particular states matters— really matters. The globalisation debate had obscured this. Our trade liberalisation concept seemed to imply government convergence, but this has simply not occurred.

‘The most difficult new challenges our national security communities need to comprehend and deal with relate to the nature of particular states in the world. Notably, I’m talking about the authoritarian governments in Russia, China, the DPRK and Iran.

‘Authoritarian states are more willing and able to use military, corporate, intelligence, economic and diplomatic tools to advance their own interests and to disrupt other governments and societies.

‘There is a real challenge to other systems of government in interacting with and relating to these governments. And many nations are still working through how this can be done so that there is cooperation in areas of mutual advantage and interests and, as importantly, there is clarity around how we will each manage areas where our national interests are quite different—in tension, or even opposed.

‘This is the nature of state-to-state interaction we see in history, but many people had perhaps lost sight of this during the high point of the era of globalisation thinking.

‘A major difference between China and the other authoritarian regimes is GDP. China’s forecast GDP for 2018 is $US13.1 trillion. Compare that with Russia’s $1.5 trillion, Iran’s $398 billion and North Korea’s $16 billion.

‘While per capita, GDP for China is still low, the Chinese state’s control means it can allocate high levels of funding to activities that are part of its longer-term plan for building influence and power. Its level of resourcing can’t be approached by the other three regimes.

‘You can see this in the scale of investment proposed under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and in case-by-case examples in countries including those in South East Asia, the Indian Ocean and the South Pacific.

‘Finance is often soft loans—which, unlike development aid, have to be paid back, which often creates considerable leverage and influence.

‘The challenges in engaging the Chinese state flow from the nature of the Chinese government (notably its control over law and over the corporate world in ways that democratic governments simply do not possess), but they also come from more practical things that are open to change should there be decisions to do so.

‘One big challenge flows from the Chinese state’s militarisation of disputed features in the South China Sea, despite an arbitral ruling from The Hague.

‘We may have different views around the tribunal (at the Permanent Court of Arbitration) and its ruling (although it is a dispute resolution mechanism state parties to UNCLOS (the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea) signed up to).

‘But the larger issue when it comes to cooperation and trust is the gap between President Xi’s words in 2015 committing not to militarise the South China Sea and the facts we see about the militarisation on the artificial structures in disputed parts of the South China Sea.

‘De-escalation of the tension in the South China Sea is possible here to the benefit of the entire region. Imagine what a message of peace dismantling of the military facilities on these disputed structures would send.

‘Returning to the Indo-Pacific map, and combining this with the global trends I have sketched out, this brings me to the ‘so what’ bit of the presentation.

‘If the Indo-Pacific is a connected system of states and economies, with interdependencies across its economies as a result, and if the global trends I sketched out briefly cannot be dealt with by any one nation acting on its own, what then is the way forward?

‘I think this was the big issue canvassed at the 2018 Shangri La dialogue— and articulated in very common ways by a considerable number of different nations’ speakers

‘Any way forward needs to do two things.

‘Firstly, it needs to deal with the large set of cumulative common challenges all of us in the Indo-Pacific face:

- those from population growth and the resulting resource pressures

- changing demographics

- mass urbanisation, particularly in low lying and coastal areas

- climate change and the effects on arable land and extreme weather events

- mass people movements resulting from these stresses

- the information explosion and technological change, and lastly

- the shift in strategic and economic weight to the Indo-Pacific.

‘All these drive connectivity and cooperation.

‘Secondly, we must be clear-eyed and honest in understanding and articulating areas where cooperation will be hardest.

‘To pretend otherwise will undermine our efforts.

‘Clear differences are appearing owing to the assertive use of economic and military power by authoritarian states. But none of us needs to take the current situation as a given. We each have agency to affect it, particularly if we work together. Seemingly intractable disputes can be resolved cooperatively—as we have seen in the recent dispute settlement between Australia and East Timor.

‘One way of integrating the areas of common purpose and those with sharper differences is through the idea of a free, open and inclusive Indo- Pacific.

‘This idea works with existing regional security institutions like ASEAN and its supporting events like the ARF and ADMM+ .

‘Indian Prime Minister Modi devoted his speech at this year’s Shangri La meeting to this vision for the Indo-Pacific. In it, he described India’s common pursuit with the US of a shared vision of an open, stable, secure and prosperous Indo-Pacific region.

‘He noted the many layered relationship India has with China, as the world’s two most populous nations and two of the fastest growing economies.

‘Japan’s Prime Minister Abe also continued to set out the shared vision of a free, open and inclusive Indo-Pacific. This year, US Defense Secretary Mattis made it the centre of his speech, as did our Prime Minister.

‘At its heart this vision recognises that rules and power interact—and it is in all states’ interests, including major powers to restrain the use of their power to allow rules to operate.

‘Such a vision involves compromise, including by great powers like China, India, the US and Japan, who might otherwise seek to dictate terms by the unilateral use of coercive power.

‘This restraint is not only possible, but it is necessary if we are to understand and address the societal, environmental and security challenges of our connected region.

‘I am confident that Australian leaders on both sides of politics see Australia as playing a constructive role as a regional partner in the Indo-Pacific, with deepening partnerships across this large region.

‘The resources committed through the Defence White Paper ensure the capacity to do so. And activism is part of our national DNA.

‘Responding to the shift in strategic and economic weight to our region is likely to drive a shift in focus in the Australian Defence Organisation back to our region, and perhaps foster even more creativity than that set out in the 2016 Defence White Paper.

‘The Australian Army has deep partnerships across the South Pacific, from Fiji, PNG, to Tonga, the Solomons and other Pacific states—and has cooperated in regional security efforts like Bougainville and RAMSI (the Regional Assistance Mission to the Solomon Islands), as well as working with South Pacific partners on peacekeeping and international deployments. ‘Similarly, the Army is part of broader regional engagement.

‘In my view though, our region’s challenges call for changes to our Defence Force’s posture and presence, with land forces playing a bigger role in this, whether through cooperation on surveillance, engineering reconstruction and peacekeeping with South Pacific partners or with South East Asian partners.

‘Prime Minister Morrison’s first overseas visit to Indonesia underlines the priority Australia is placing on growing our strategic partnership with Indonesia. And army-to-army cooperation will, along with maritime security and surveillance, be a big part of that agenda; in part because of the prominence in Indonesia of its land force.

‘At the same time, the requirements for our ADF to contribute to deterring high-end conflict remain. This is the driver of the land force modernisation program you’ll no doubt hear a lot more about over the next few days.

‘Armies and defence forces are at their best when they are working together to prevent and deter conflict, and when their capabilities and their professionals can be used in support of civilian needs.

‘The good news is that the list of global challenges with prominence in the Indo-Pacific where armies can cooperate like this in coming decades is long. I look forward to hearing more about your deliberations.

‘Thank you.’

Figure 13. Members of the Australian Army, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army, US Army and US Marine Corps are welcomed to Darwin to commence Exercise Kowari, a tri-lateral exercise to foster trust and cooperation between the three nations through an outback survival exercise with the Australian Army’s Regional Force Surveillance Unit, NORFORCE. (Image: DoD)