Abstract

This article analyses Australia’s readiness to manage a complex cyber- catastrophe. It contains an analysis of both military and civilian publicly available documentation pertinent to Australia’s cyber capability and disaster resilience. The findings suggest that Australia is ill-prepared to respond adequately to the kind of complex cyber-attack that may trigger cascading consequences. This article seeks to evaluate the scope of Australian documents in the public domain that address cyber-security and disaster resilience. The article compares the way in which Australia and the United States have developed strategic and military cyber policies in order to determine the implications for Australia’s readiness to manage a multi-vector, complex cyber-catastrophe. The results highlight distinct vulnerabilities in Australia’s current position and evidence reveals inconsistencies in policy development and the use of cyber terminology. Analysis of existing policies and strategic documentation additionally demonstrates elements of non-compliance with both current Australian strategies and recommendations for national resilience espoused by the United Nations.

Introduction

This article is a public policy analysis prepared in the Australian Centre for Cyber Security. It seeks to deliver a multi-disciplinary approach to the discovery of Australia’s readiness if confronted with a complex cyber- catastrophe involving multiple and/or simultaneous attacks against civilian and military systems. This article explores the extent to which the language of cyber is codified across Australian agencies and internationally. Furthermore, it examines the hierarchical response structure of the United States and of Australia, reflecting upon the advantages of each country’s strategic planning.

Fred Kaplan1 documents the history of US approaches to cyber warfare in his book Dark Territory. Clarke and Knake 2 highlight future threats in their book Cyberwar with reference to a coordinated response to a zero-day broad spectrum cyber-attack on the US. Macdonald et al,3 warn us that coordinated or sustained cyber-attacks upon aspects of everyday life (in a hyperconnected world) might result in far more damage to our social order than any spectacular ‘one-off’ style attack. All three texts focus on the vulnerabilities and disruptive, destructive powers of cyber-attacks, raising questions about the nature and extent of any country’s military and civilian capacity to secure its cyberspace.

These three books raise the spectre of a complex cyber-catastrophe, which is understood by the US Department of Defense as the ‘cascading failures of multiple, interdependent, critical, life-sustaining infrastructure sectors’4 and the consequential large-scale destruction and devastation. The definition of a complex cyber-catastrophe is informed by the work of Austin 5 and security experts Clarke and Knake 6 and takes into account current definitions in the US Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms.7 Also considered is Australia’s former Cyber Minister Dan Tehan’s reference to ‘A Cyber Storm’.8 On this basis, this article defines a complex cyber- catastrophe as ‘a multi-vector, multi-threat cyber-attack that triggers cascading effects’.

At the time of writing, there had been little public discussion of Australia’s cyber-security and strategies for defence against such a multi-vector threat. This is despite the scale and increasing frequency of attacks on Australia and the accepted practice of Australia’s closest allies to address the topic coherently and comprehensively in the public domain. Austin asserts that Australia ‘does not … possess such capabilities [systems of decision- making for a complex cyber-catastrophe] nor is it close to achieving them. It has not even begun planning for most of them’.9

While the Australian government, the Australian Defence Force and the commercial sectors have their own unique ways in which they identify and manage cyber problems, there is little evidence in the public domain of policy, research and training that are directly relevant to all three as a whole-of-nation defence strategy in a complex cyber emergency. In 2013, Jennings and Feakin argued that ‘significantly more needs to be done to ensure that Australia has the right policies in place to manage cybersecurity risk’.10 In 2016, Austin highlighted the ‘need for … a comprehensive, public domain study, advocating that “no government … can afford to undertake policy analysis of military cyber needs largely behind the veil and without clear benchmarks”’.11 Finally, in 2017, the G7 called for nations to strengthen their critical infrastructure against ICT threats.12 To further Austin’s argument surrounding clear benchmarks, the NATO National Cyber Security Framework Manual stipulates the rarity of explicit definitions in many common cyber terms such as ‘national cyber security’.13 Even the spelling of key words such as ‘cyber security’ is inconsistent at national levels, Australia included.

Keliiaa and Hamlet identify seven security problems within the cyber domain,14 all of which are rarely canvassed publicly in Australia.

- disjointed response to wide-area and multi-target attack

- widely dispersed and fragmented detection and notification capabilities

- ill-defined government, commercial, and academic roles and responsibilities

- divided and rigid wide-area cyber protection posture

- unresolved wide-area common and shared risks

- fragile interdependent wide-area critical access and operations

- unresolved attribution of attack and compromise.

While this article has not been structured around these problems, their application to complex cyber-catastrophes will become apparent in discussion that follows.

Analysis of the ‘Cyber’ Discourse

While the details of Australia’s cyber capabilities remain classified, it is possible to examine Australian policy and planning in relation to the nation’s preparation for a complex cyber-catastrophe. This study entails a meta-analysis of the available academic, government and private sector documents seeking to understand the inter-relationships between actors and preparedness in the event of a cyber-enabled attack. In the first instance this involves an analysis of the cyber discourse. This involves a close examination of the frequency, variations in meaning and mode of the cyber language—comparing the cyber discourse of international documents with that of Australia’s—and is underpinned by critical theory. The novelty of the cyber discourse focuses attention on the basic set of concepts reflecting Australia’s preparedness for a complex cyber- catastrophe.

For the purposes of this article, the term ‘discourse’ relates to the ‘formal treatment of a subject in speech or writing’15 and assumes that the speaker/ author seeks to influence the audience in a particular way.16 Discursive analysis offers a method of ‘analysing stretches of interaction, rather than isolated phrases’17 and is concerned with ‘understanding and interpreting socially produced meanings’.18 In this instance, the analysis draws upon both quantitative and qualitative methods. It focuses on the language, meanings and usage (including frequency and mode) and any variations thereof found within the cyber discourse. Key terms as defined in the NATO National Cyber Security Framework Manual: Cyber, Information Security, ICT Security, Cyber Security, Cyber Crime, Cyber Espionage and Cyber Warfare19 have been identified, along with terms commonly used in Australian documents.20

Karabacak et al argue that:

‘… little, if any, research is dedicated to maturity assessments of national critical infrastructure protection efforts. Instead, the vast majority of studies merely examine diverse national-level security best practices ranging from cyber-crime response to privacy protection.’ 21

During the analysis, government and military dictionaries and glossaries were accessed 22 to discern the extent that the cyber discourse is standardised and codified across the stakeholder communities and whether the language of the community has become both explicitly and implicitly normative.23 The definitional analysis aims to highlight the standards set down by particular knowledge systems24,be they governments, departments, agencies or authorities. This is significant because unless meaning is clear and connotes authority25, consistent communication will remain elusive and, at best, unreliable. The entry of ‘cyber’ into the civilian and military discourses is also ‘inextricably linked to questions of authority’.26 Therefore, a discursive analysis can reveal the nature of connoted institutional power 27 and the way in which the cyber discourse signifies political and ideological bases.28

Government Policy

The NATO National Cyber Security Framework Manual 29 provides the foundations for cyber-security policy development. This document is not restricted in its relevance to NATO members but is pertinent to any emerging national cyber-security strategy. While other publications have sought to provide cyber-security policy makers with specific elements and direction relating to one particular view point, the NATO National Cyber Security Framework Manual offers a broader and more rounded perspective.30

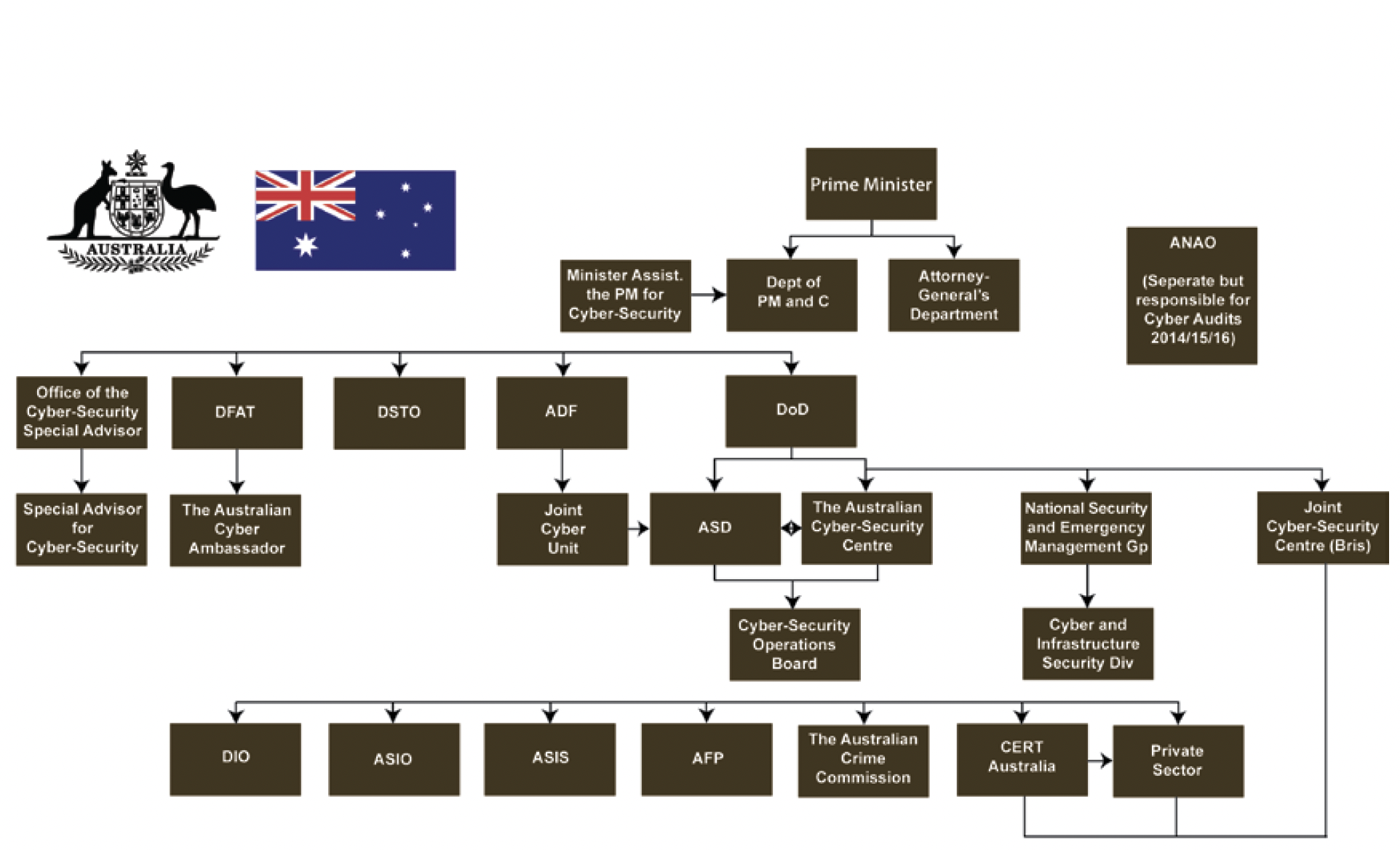

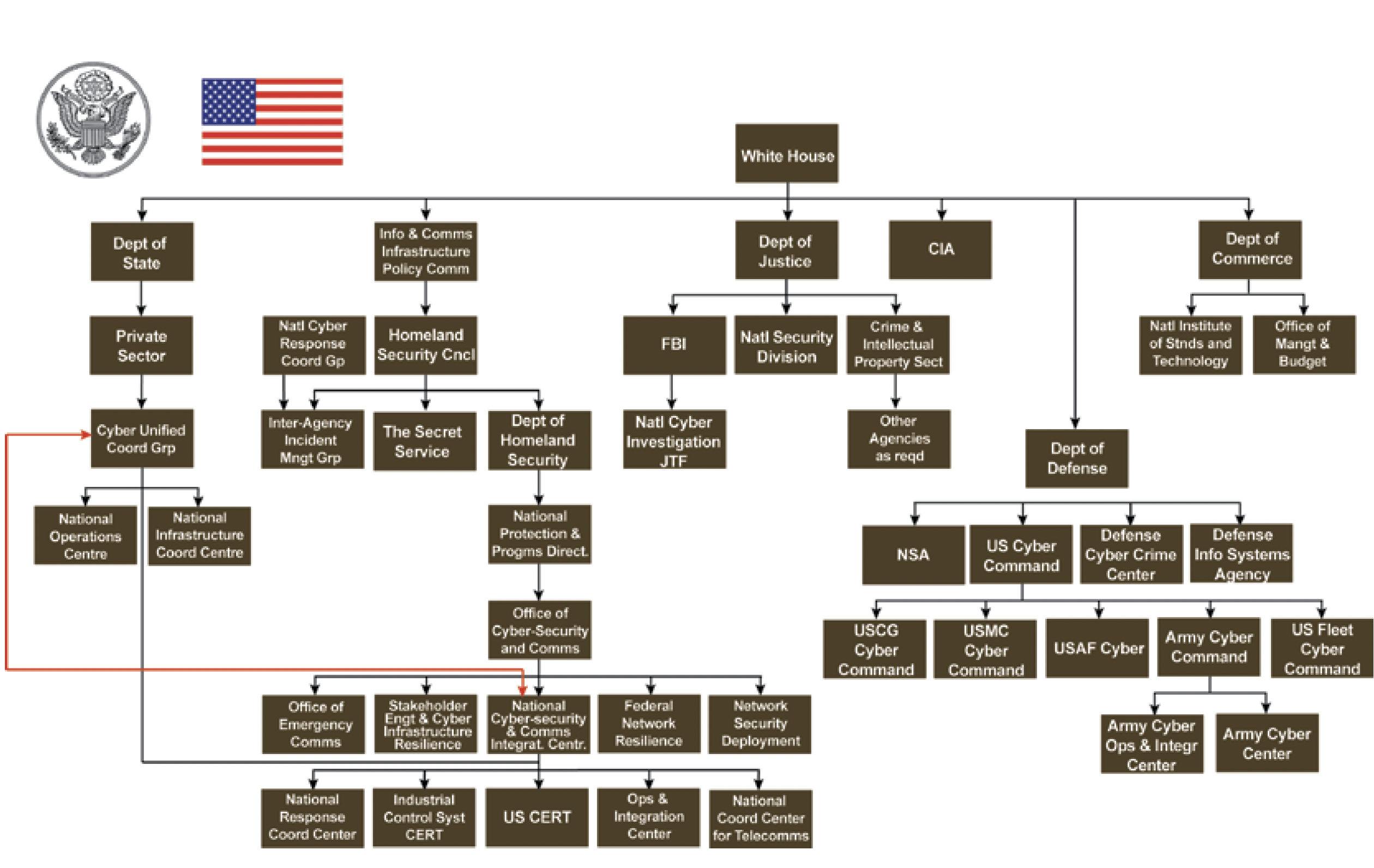

At the highest level of consideration, the NATO National Cyber Security Framework Manual 31 outlines the importance of cooperation and consistency between nations when defining cyber terms. Unfortunately, global international consensus has not been reached. As such, this article compares US and Australian approaches to discern best practice. The understanding that the US is the most developed of the Five Eyes nations stems from an analysis of national cyber strategy documents and organisational structure, as represented in Figures 1 and 2, and known / suspected involvement in international cyber-operations.32

The extent of the definitional problem appears widespread according to the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence (CCDCOE), which notes that while the term ‘national cyber security’ is often used in policy documentation, it is rarely defined.33 This trend continues across much of the cyber discourse where universally accepted definitions are rare and ‘as a rule, the individual national context will define the specific definitions, which in turn will define the specific approaches’.34 Key terms defined by CCDCOE are as follows: Cyber, Information Security, ICT Security, Cyber

Security, Cyber Crime, Cyber Espionage and Cyber Warfare.35 Within each, sub definitions are also characterised with different examples provided across nations. These terms have been cross referenced between the US and Australia using significant public documents released since 2004. Through this analysis, the trend identified by CCDCOE was confirmed with each nation and even individual agencies within each nation are defining and spelling cyber terms differently.

Current Government Structure and Cyber-Security

Stallard asserts that ‘the [Australian] government has designated the Department of Defence to be the operational lead on governmental cybersecurity operations’.36 Despite this argument, the organisational responsibilities and overarching command authority remain ambiguous in the public domain. Despite this designation, Australia still lacks either a public strategic or policy document that ‘guides the department’s and the ADF’s approach to cyber threats’.37 It is possible, but unclear, that with the development of the ACSC (Australian Cyber Security Centre), the Defence Department will assume the overarching role, with the ADF limited to securing and combatting military capabilities. This confusion is diagrammatically represented in Figure 1. Although the Prime Minister appears to have ultimate control through the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, various organisations and sectors receive multiple inputs with no clearly designated authority. Clarke and Knake highlight the folly of this situation when they hypothesise a complex catastrophe.38

Figure 1 indicates that the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet dictates to the Department of Defence in terms of cyber-strategy, while the Attorney-General’s Department controls National Security and Emergency Management. This contrasts with the devolution of responsibility in the US, where the Department of Homeland Security oversees all critical infrastructure and government networks minus the .mil domain which is overseen by defence specialists (see Figure 2). Figure 2 clearly illustrates the linear devolution of authority and responsibilities in the US, whereas Figure 1 highlights an Australian model that is more convoluted and potentially ineffective in the event of a complex catastrophe given its apparent lack of dedicated command.

Figure 1. Australian Cyber Higher Government Organisational Structure 39

Figure 2. United States Cyber Higher Government Organisational Structure 40

Australia’s emergency response plans are managed by the Attorney- General’s Department, which parallels the US Department of Homeland Security. These plans comprise the Australian Government Disaster Response Plan, Australian Government Overseas Assistance Plan, the Australian Government Plan for the Reception of Australian Citizens and Approved Foreign Nationals Evacuated from Overseas, Australian Government Aviation Disaster Response Plan, Australian Government Space Re-entry debris plan and the National Catastrophic Natural Disaster Plan.41 It should be noted that not one of these plans mentions cyber, nor do they provide guidelines for Australia’s response in the event of a complex cyber- catastrophe.

Australia’s capacity to respond to a complex catastrophe is limited by the scope and scale of Australia’s emergency response planning. Based on information in the public domain, Australia has not planned specifically for a cyber incident. Defence policy, which highly classifies cyber capability,42 may include a response mechanism for government; however, this does not aid public organisations such as critical infrastructure to prepare for, or adequately respond to, the cascading nature of a complex catastrophe.

In contrast, the US has a nested framework of incident management and response, which allows the government to plan for many previously considered disasters while maintaining flexibility to adapt well to unforeseen events. This is not apparent in Australia’s documentation; however, if the Australian Government received a request from a State or Territory Government for assistance, the Australian Government Disaster Response Plan offers a framework response. Australia’s official response to a complex cyber catastrophe is unknown and the lack of a public emergency response plan that deals with this scenario is of concern.

The most detailed and cyber-specific US response framework is the National Cyber Incident Response Plan,43 which is an updated version of a 2004 document and can be considered an operational planning document that has four focused priorities: threat response, asset response, intelligence response and affected entity response.

The National Incident Cyber Response plan highlights fourteen core capabilities vital to the lines of effort and response to a cyber incident.44 These are:

- Access control and identity verification

- Cyber-security

- Forensics and attribution

- Infrastructure systems

- Intelligence and information sharing

- Interdiction and disruption

- Logistics and supply chain management

- Operational communications

- Operational coordination

- Planning

- Public information and warning

- Screening, search, and detection

- Situational assessment

- Threats and hazards identification

In addition to this understanding, the comprehensive nature of the National Cyber Incident Response Plan and the capacity to rapidly mobilise the National Cyber Response Coordination Group (NCRCG), which is directly responsible to the President (See Figure 2), epitomises the scope and scale of an effective readiness framework in the event of a complex cyber- catastrophe. The Inter-Agency Incident Management Group is subordinate to the NCRCG and is tasked with ensuring effective communication and oversight between sectors. This is made possible by the group’s dynamic nature, tailored to the specific incident. This flexibility and forward planning in alignment with the National Cyber Response Plan gives the United States a profound advantage in command and control in the event of a cyber- emergency.

Along with a comprehensive emergency management framework, the US information sharing program is of importance45 and is exemplified by the comprehensive nature of the Department of Homeland Security’s information sharing network, which contains analysis, automated indicator sharing and a 24/7 situational awareness incident response and management centre.46

The owners and operators of critical infrastructure in the US and Australia voluntarily participate in information sharing, as the respective governments have the expectation that the owners and operators are responsible for network security. By comparison, the Government of the United Kingdom takes this a step further by mandating that the ongoing testing for cyber- security in critical infrastructure must be conducted in partnership with government bodies and regulators and, where it is found lacking or derelict, Her Majesty’s Government will ‘intervene in the interests of national security’.47 While both the US and Australia are working on similar legislation,48 none is currently active.

In Australia, mutual exchange of information occurs in part between the ACSC, the Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT) Australia and critical infrastructure. The Trusted Information Sharing Network (TISN)— encompassing State, Territorial and Federal Governments and the owners and operators of critical infrastructure—provides a secure environment for the communication of sensitive information. The Critical Infrastructure Advisory Council, located within the auspices of the Attorney-General’s Department, provides governance and strategic direction for the TISN.49 Australia’s Critical Infrastructure Resilience Strategy adopts a non-regulatory approach, in that it assumes that ‘owners and operators of critical infrastructure are best placed to assess the risks to their operations and determine the most appropriate mitigation strategies’.50

Although the civilian sector remains uncontrolled—which poses a problem given that around eighty percent of critical infrastructure in Australia is privately owned—the Australian Signals Directorate (ASD) has produced the Australian Government Information Security Manual (ISM), which governs the security of government ICT systems.51 The ISM is a three-part document that outlines requirements at the executive, user and administrator-specific level in a bid to secure government networks. In 2014, the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) conducted an audit of seven government entities regarding their compliance with the top four strategies within the ISM.52 These are, in turn: application whitelisting, patch applications, patch operating systems and restrict administrative privileges. These seven departments comprised: the Australian Bureau of Statistics, Australian Customs and Border Protection Service, the Australian Financial Security Authority, the Australian Taxation Office, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Department of Human Services and IP Australia (Patent Office).53

Of these seven departments, none were compliant. This resulted in the re- investigation of three of these entities over 2015-2016, namely the Australian Taxation Office, the Department of Human Services and the Department of Immigration and Border Protection. It was noted that ‘all entities made efforts to achieve compliance’,54 however,

‘…only the Department of Human Services was assessed as having effectively implemented application whitelisting. The Department of Immigration and Border Protection had an application whitelisting strategy but deviated from it. The Australian Taxation Office only developed an application whitelisting strategy during the course of this audit.’ 55

Furthermore, only the Department of Human Services was deemed cyber-resilient.56 While there is at least legislation mandating the security requirements of government networks, the challenge clearly lies in the application. This lack of compliance is perhaps understandable, given the limited budgetary allocations to ICT and cyber-security. Also, it should be acknowledged the many different departments within government coordinate their own ICT infrastructure making it difficult to achieve consistency across government. On 24 February 2017, the Joint Cyber Security Centre was launched as a pilot program based in Brisbane, Queensland.57 The organisations participating in the first instance are as follows: Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission, the Australian Federal Police, Brisbane Airport Corporation, CERT Australia, Commonwealth Bank, Credit Union Australia, Origin Energy, Powerlink, Qantas, Queensland Government Chief Information Officer, Queensland Rail, Queensland Urban Utilities, Rio Tinto and Telstra.58

A non-exhaustive example of those missing from this list are: the Queensland Emergency Services, Regional Airports, Maritime Port Authorities, Queensland Health and representatives from the agriculture, scientific and education sectors. The 2017 Cybersecurity Report promotes Australia as being ‘at the forefront of developments in safety and security in the online environment with robust legislation, advanced law enforcement capability, rigorous policy development and strong technical defences’.59

None of the educational or research bodies identified in this document are based in Queensland, nor are they participants in the pilot Joint Cyber Security Centre program. In addition, the Statement of Intent for the program incorporates that solutions to cyber-security risks are to be developed through collaboration and without commercial bias, as a strategic objective.60 The pilot program includes only two banks, one telecommunications company, one airline and one mining company.61 Together with the aforementioned omissions, the location and scope of the pilot program are moot.

National Security

In 2016, the UK published its National Cybersecurity Strategy, which signified that the government’s policy was an ‘unprecedented exercise in transparency’,62 openly acknowledging that discussions about national cyber-security could ‘no longer … [remain] behind closed doors’.63 That same year, Austin problematised the fact that, to date, there had been

‘…no effort in public by the government to benchmark Australian national security needs in cyberspace in the same way as we benchmark naval, air and ground capability against strategic needs (strengths & weaknesses of potential enemies and their intentions).’ 64

The 2009 Defence White Paper acknowledges the ‘growing importance of operations in cyberspace’65 due to the way in which national security could potentially be ‘compromised by cyber-attacks on our defence, wider governmental, commercial or infrastructure-related information networks’.66 However, there is no mention of making the discussion public. In fact, this paper states explicitly that ‘many of these capabilities remain highly classified, but in outline they consist of a much-enhanced cyber situational awareness and incident response capability’.67 Similarly, the 2016 Defence White Paper prioritises ‘investment in modern space and cyber capabilities and the infrastructure, information and communications systems that support defence capability’.68 This White Paper was ostensibly the result of ‘a comprehensive consultation process’,69 incorporating input from ‘Government, the Australian defence industry and the Australian public’,70 but there is no acknowledgement of the need for, or advantages of, public transparency.

The 2016 US National Cyber Incident Response Plan is authored by representatives from both government agencies and the private sector and emphasises the plan as a ‘whole-of-Nation concept’.71 It does so by acknowledging that Government resources and expertise alone cannot adequately respond to the needs of those targeted by cyber-attacks and that responsibility must be borne collectively by individuals, the government and the private sector.72 In this way, all elements of the community ‘must be activated, engaged, and integrated to respond to a significant cyber incident’.73

From an Australian perspective, the paper Australia Rearmed! Future Needs for Cyber-Enabled Warfare recommends that Australia builds ‘a much more visible community of interest around the concept of cyber-enabled warfare’.74 Austin also concurs with US NSA Chief, Admiral Rogers’ assessment of the value of providing common language.75 The proposition of scenario development to aid in cyber-security development is also foregrounded by Austin.76 He suggests a series of events77 not dissimilar to Tehan,78 which would enable planning for such a complex cyber- catastrophe, reducing the likelihood of strategic surprise.79 The US is the only Five Eyes nation to announce the conduct of such an exercise which meets the definitional requirements for a complex cyber-catastrophe.80 This raises the question as to the preparedness of Australia in similar circumstances.

There is also a disparity between nations as to how much effort and capital is dedicated to cyber-security. The United States committed $26 billion over the 2017 Fiscal Year alone and has run a biennial state-sponsored cyber exercise called Cyber Storm since 2006. Each exercise has specific goals, however, the intent is to strengthen national critical infrastructure resilience in the US and partner countries. While participation is voluntary among privately-owned organisations, many still choose to participate and it offers them a means to identify cyber-security shortfalls.81 Despite this, as recently as 2012, Newmeyer took issue with ‘a hodgepodge of initiatives and good ideas, but no unifying focus’82 implemented across sectors in the US.

In the UK, the CERT UK team supports, on average, three cyber exercises per month to test cyber resilience and response83 and provisions £1.9 billion over five years based on a similar plan to the US.84 In the same time period, Australia has committed just $100 million over one year85 and has decreased its involvement in the Cyber Storm exercises,86 relying on industry to make its own decisions based on the TISN and their own assessments.87

Disaster Resilience

Former Director of the FBI, Robert Mueller warns that ‘There are two types of companies: those that will be hacked and those that have been hacked and will be hacked again’;88 a concept that has failed to generate traction in Australia. According to Jaeger,89 cyber-attacks are inevitable. Due to the dynamic and agile nature of cyber-weaponry, joint exercises thus become an imperative; not to eradicate the possibility of cyber-attack, as is arguably impossible, but to mitigate the effects and to learn how to respond in an emergency.90 The Australian Centre for Cyber Security highlights the shortfalls in Australia’s preparedness in the event of a cyber-enabled attack in a series of papers published through the University of New South Wales, Canberra.91 The primacy of a cyber- threat to national security is highlighted by the budgetary commitments of the US and UK above.

In terms of disaster resilience and management, communication and public discussion are manifestly important for assessing and effectively managing disasters.92 The International Strategy for Disaster Reduction, Hyogo Framework for Action 2005-2015 highlights the ‘increasing vulnerabilities related to changing … technologies’, ‘technological hazards’93 and the need for the sustainability of infrastructure,94 although the term ‘cyber’ is silenced. While cyber-security has been identified as a key area of risk for Australia’s security, the broad parameters and specific nature of threats are not well understood by the general population. This is evidenced by the ‘critical shortage of suitably trained and qualified cyber professionals, and current [Science and Technology] S&T investment [that] does not match the magnitude of the problem space’.95

Public education and communication entails open discussion of risk and is advocated by the Australian Disaster Resilience Strategy as a means of effectively anticipating risk.96 This document emphasises the fundamental nature of knowledge and the communication of ‘all relevant and available information’97 not only in disaster management but in preparation and risk mitigation, thereby building a culture of resilience across all levels of the community. This is further endorsed in the National Strategy for Disaster Resilience: Companion Booklet, which advocates ‘a partnership approach with key stakeholders to convey the disaster resilience message’.98 On the surface, this community-wide ‘culture’ provides a firm foundation for a whole-of-nation approach to national security that includes cyber.

Mayfield’s Paradox offers a mathematical proof that an infinite amount of money would need to be spent to completely eradicate a cyber-threat,99 thus implying that systems’ administrators and programmers will never be able to entirely secure their systems. This makes Australia’s Disaster Resilience Plan relevant to Australia’s cyber-security. A key concern is that official documents fail to outline cyber-specific policy and protocols. Turnbull and Ormrod100 suggest a Military Cyber Maturity Model (MCMM). The MCMM recognises the likelihood of an enemy using a zero-day exploit to attack a system. As such, instead of attempting to completely reduce all vulnerabilities, the model plans to combat the consequences.101 This is an effective methodology, however the threat must first be understood and this requires a sharing of information.

Effective national and regional management of a disaster relies upon national and local risk assessments and the regular dissemination of up-to-date data and risk maps to enable decision makers and the public to effectively assess the impact of a disaster.102 Thus the advocacy for public discussion and access to information for disaster mitigation and management is noteworthy

Conclusion

This article began by recognising the importance of standardised cyber discourse and identifying that, for any communication to be effective, a singular definitive point of reference that codifies the normative use of terminology needs to be in place. This is broadly the case within US documents, through the US Department of Defense’s Dictionary of Military Terms. In contrast, Australian cyber security policy and defence capability is stunted and incomplete. The meaning and use of cyber terminology is unstable and varied. These policy inconsistencies have implications for Australia’s national security and identify some of the vulnerabilities in Australia’s whole-of-nation national security outlook, raising concerns over the preparedness of Australia’s policy if confronted with a complex cyber- catastrophe.

Across Australia’s emergency response plans for specific major incidents, there is no mention of ‘cyber’. Neither the National Catastrophic Natural Disaster Plan nor Australian Government Disaster Response Plan deal specifically with the nuances of a complex cyber-catastrophe and it is unlikely that these plans provide an adequate framework or coherent understanding of such an event. A country with ill-defined responsibilities and chain of command and without a response plan for a complex cyber- catastrophe becomes what Austin calls the ‘kingdom of the blind’.103 Cyber-capability in Australia remains classified but what is clearly evident is Australia’s vulnerability and lack of preparedness in the event of a complex cyber-catastrophe. Thus, there is a clear imperative for Australia to continue to develop its cyber strategy and resilience.

Further research opportunities exist with regard to a detailed analysis of cascading effects in the Australian cyber environment and the impact of changes implemented, due to recommendations made in the 2017 Independent Intelligence Review and the future development of the Department of Home Affairs.

Endnotes

- F Kaplan, 2016, Dark Territory, New York: Simon & Schuster

- RA Clarke and RK Knake, 2012, Cyberwar: The next threat to national security and what to do about it, New York: Ecco

- S Macdonald, L Jarvis and TM Chen, 2014, Putting the ‘Cyber’ into Cyberterrorism: Re-Reading Technological Risk in a Hyperconnected World in: Cyberterrorism : Understanding, Assessment, and Response, New York: Springer, pp 43-83

- US Department of Defense, 2017, DoD Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, US Department of Defense

- G Austin, 2016, ‘Australia Rearmed! Future Needs for Cyber-Enabled Warfare’, Canberra: University of New South Wales, Canberra

- Clarke & Knake, 2012

- US DoD, 2017

- D Tehan, 2016, Address to the National Press Club, ‘A Cyber Storm’, Canberra: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet

- G Austin, 2017, ‘Are Australia’s responses to cyber security adequate?’, in: M Cilento, ed. Australia’s place in the world, Melbourne: Committee for Economic Development of Australia, pp 50-60, p 55

- P Jennings and T Feakin, 2013, Special Report: ‘The Emerging Agenda for Cybersecurity’, Canberra: Australian Strategic Policy Institute, p 1

- Austin, 2016, p4

- G7 Foreign Ministers, 2017, G7 Declaration on Responsible States Behaviour in Cyberspace, Lucca: G7

- NATO CCDCOE, 2017, About Cyber Defence Centre, at: https://www.ccdcoe.org/ about-us.html accessed 3 Aug 2017

- CM Keliiaa and JR Hamlet, 2010, ‘National Cyber Defense High Performance Computing and Analysis: Concepts, Planning and Roadmap’, Albuquerque: Sandia National Laboratories, p8

- S Mills, 2004, Discourse: The New Critical Idiom, 2nd ed Abingdon (Oxfordshire): Routledge, p 1

- Mills, 2004, p 4

- Mills, 2014, p 126

- D Howarth, 2000, Discourse, Buckingham, UK: Open University Press, p128 19. NATO, 2017, pp 9-19

- Australian Army, 2008, Australian Army Land Warfare Doctrine LWD 6-0 Signals, Canberra: Australian Army; Department of Defence, 2009 Defence White Paper - Defending Australia in the Asia Pacific Century: Force 2030, Canberra: Australian Department of Defence; S Day, 2011, Future Joint Operating Concept 2030, Canberra: Australian Defence Force; Australian Air Force, 2011, The Airforce Approach to

- ISR, Canberra: Australian Air Force; Attorney-General’s Department, 2012, National Strategy for Disaster Resilience: Companion Booklet, Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; A Hawke and R Smith, 2012, Australian Defence Force Posture Review, Canberra: Australian Government; Australian Defence Doctrine Publication, 2013, Operations Series: ADDP 3.13 Information Activities, Canberra: Australian Defence Force; Australian Cyber Security Centre, 2015, ACSC 2015 Threat Report, Canberra: Australian Cyber Security Centre; Australian Cyber Security Centre, 2016, ACSC 2016 Threat Report, Canberra: Australian Cyber Security Centre; Australian Air Force, ND, Air Force Strategy 2017-2027, Canberra: Australian Air Force

- B Karabacak, SO Yildirim and N Baykal, 2016 ‘A vulnerability-driven cyber security maturity model for measuring national critical infrastructure protection preparedness’, International Journal of Critical Infrastructure Protection, Vol 15, pp 47-59

- US DoD, 2017, Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms; US Department of Homeland Security 2016, National Cyber Incident Response Plan, US Department of Homeland Security; US Department of Defense, 2015, The DoD Cyber Strategy, Washington: US Department of Defense; Center for Strategic Leadership, 2016, Strategic Cyberspace Operations Guide, United States Army War College, Carlisle; Australian Defence Doctrine Publication, 2013, Operations Series: ADDP 3.13 Information Activities; Australian Army, 2008, LWD 6-0 Signals; ACSC, 2015, Threat Report

- N Fairclough, 1992, Discourse and Social Change, Cambridge: Polity Press, p 190

- R Visker, 1992, ‘Habermas on Heidegger and Foucult: meaning and validity in Philosophical Discourse on Modernity’, in Radical Philosophy, Vol 61, pp 15-22

- Attorney-General’s Department, 2012, National Strategy for Disaster Resilience: Companion Booklet, p 14

- Mills, 2004, p 46

- TA Van-Dijk, 2008, Discourse and Power, Basingstoke (Hampshire): Palgrave MacMillan, p37

- Fairclough, 1992, p 77

- NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence, 2012, National Cyber Security Framework Manual, Tallinn: NATO CCDCOE

- NATO, 2012, p 191

- NATO, 2012, p 191

- Kaspersky, 2015, Targeted Cyberattacks Logbook, at: https://apt.securelist. com/#secondPage, accessed 30 Jun 2017

- NATO, 2012, pXV

- NATO, 2012, pXV

- NATO, 2012, pp 9-19

- C Stallard, 2011, ‘At the Crossroads of Cyberwarfare: Signposts for the Royal Australian Air Force’, Montgomery(Alabama): School of Advanced Air and Space Studies

- T Feakin, J Woodall and L Nevill, 2015, Cyber Maturity in the Asia-Pacific Region 2015, Canberra: Australian Strategic Policy Institute, p 20

- Clarke and Knake, 2012

- Attorney-General’s Department, 2015, Critical Infrastructure Resilience Strategy: Policy Statement, Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; Attorney-General’s Department, 2009, Cyber Security Strategy, Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; Attorney- General’s Department, 2017, CERT Australia, at: https://www.cert.gov.au/, accessed 1 Oct 2017; Attorney-General’s Department, 2017, Critical Infrastructure Resilience, at: https://www.ag.gov.au/NationalSecurity/InfrastructureResilience/Pages/d…, accessed 5 Sep 2017; Attorney-General’s Department, 2017, Joint Cyber Security Centre: Partner Organisations, Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; Australian Cyber Security Centre, 2017, ACSC 2017, Threat Report, Canberra: Australian Cyber Security Centre; Australian National Audit Office, 2017, Cybersecurity Follow- up Audit: Across Entities (Report Number: 42 of 2016-2017), Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, 2016. Australia’s Cyber Security Strategy, Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; Jennings & Feakin, 2013

- Kaplan, 2016; P Piret, W Jesse and VK Alexander, 2016, National Cyber Security Organisation: United States, Tallinn: NATO CCDCOE; US Department of Defense, 2015, The DoD Cyber Strategy, Washington: US Department of Defense; DHS, 2016; US Department of Homeland Security, 2017, National Incident Management System, at: https://www.fema.gov/national-incident-management-system, accessed 27 Jul 2017

- Attorney-General’s Department, Emergency response plans, at: https://www.ag.gov. au/EmergencyManagement/Emergency-response- plans/Pages/default.aspx, accessed 22 Jun 2017

- Department of Defence, 2009

- DHS, 2016

- DHS, 2016

- Department of Homeland Security, 2016, Cyber Information Sharing and Collaboration Program, at: www.dhs.gov/cisp , accessed 12 Sep 2017

- DHS, 2016

- Government of the United Kingdom, 2016, National Cyber Security Strategy 2016- 2021, London: HM Government, p 41

- Clarke and Knake, 2012; Kaplan, 2016; Attorney-General, 2017

- Attorney-General’s Department, 2015, ‘Trusted Information Sharing Network: For Critical Infrastructure Resilience’, Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia

- Attorney-General’s Department, 2015, p 5

- Australian Signals Directorate, 2017, ‘Australian Government Information Security Manual’, at: https://www.asd.gov.au/infosec/ism/, accessed 22 Jun 2017

- Australian National Audit Office, 2016, ANAO Report No.37, 2015–16, Cyber Resilience, Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia

- Australian National Audit Office, 2016

- Australian National Audit Office, 2016

- Australian National Audit Office, 2017, Cybersecurity Follow-up Audit: Across Entities (Report Number: 42 of 2016-2017), Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, p 10

- Australian National Audit Office, 2017, p 8

- Attorney-General’s Department, 2017, Joint Cyber Security Centre, at: https://www. jcsc.gov.au/, accessed 12 Sep 2017

- Attorney-General’s Department, 2017

- Australian Trade and Investment Commission, 2017, ‘Cyber Security’, Sydney: Commonwealth of Australia, p 4

- Attorney-General’s Department, 2017, Joint Cyber Security Centre: Statement of Intent, Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia

- Attorney-General’s Department, 2017

- Government of the United Kingdom, 2016, p 6

- Government of the United Kingdom, p 6

- Austin, 2016, p 2

- Department of Defence, 2009, p 83

- Department of Defence, 2009, p 83

- Department of Defence, 2009, p 83

- Department of Defence, 2016, p 10

- Department of Defence, 2016, p 14

- Department of Defence, 2016, p 14

- Department of Defence, 2016, p 6

- Department of Defence, 2016, p 7

- Department of Defence, 2016, p 6

- Austin, 2016, p i

- Austin, 2016, p 27

- Austin, 2016, p 27; NATO, 2007, ‘The Use of Scenarios in Long Term Defence Planning’, at: https://plausiblefutures.wordpress.com/2007/04/10/the-use-of- scenarios-in-long-term-defence-planning/, accessed 16 Nov 2017

- Austin, 2016, p 28

- Tehan, 2016

- Austin, 2016, p 27

- Austin, 2016, p 27

- US Department of Homeland Security, 2011, ‘Cyber Storm III Final Report’, Washington: July; US Department of Homeland Security, 2016, ‘Cyber Storm V Final Report’, Washington: Department of Homeland Security; US Department of Homeland Security, 2016, ‘Cyber Storm: Securing Cyber Space’, at: https://www.dhs.gov/cyber- storm, accessed 23 May 2017

- KP Newmeyer, 2012, Who Should Lead US Cybersecurity Efforts?, Prism, Vol 3, Issue 2, pp 115-126

- UK Cabinet Office, 2016, ‘The UK Cyber Security Strategy 2011-2016 Annual Report’, London: Cabinet Office

- TRHG Osborne, 2015, ‘Chancellor’s speech to GCHQ on cyber security’, London: HM Treasury Government Communications Headquarters

- G Austin and J Slay, J, 2016, ‘The Australian government must take cyber security more seriously’, The Conversation, 1 Jun

- DHS, 2011; DHS, 2016

- Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, 2016; Attorney-General’s Department, 2016

- Jaeger, J, 2012, Preparing for the inevitable Cyber-attack, Compliance Week, Apr, p 12

- Jaeger, 2012

- Jaeger, 2012

- UNSW Canberra, 2017, Australian Centre for Cyber Security, at: https://www.unsw. adfa.edu.au/australian-centre-for-cyber-security/, accessed 15 Dec 2017

- United Nations, 2005, ‘Hyogo Framework for Action 2005-2015: Building the Resilience of Nations’, United Nations

- United Nations, 2005, p 1

- United Nations, 2005, p 8

- Defence Science and Technology Organisation, 2014, ‘Cyber 2020 Vision: DSTO cyber science and technology plan’, Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, p 8

- Council of Australian Governments, 2011, National Strategy for Disaster Resilience, Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia

- Council of Australian Governments, 2011, p 8

- Attorney-General’s Department, 2012, p 14

- Mayfield and ND Cvitanic, ‘Mathematical Proofs of Mayfield’s Paradox: A Fundamental Principle of Information Security’, at: https://hackerfall.com/story/mayfields-paradox-a- fundamental-principle-of-infor, accessed 6 Sep 2017

- Ormrod, D & Turnbull, B, 2015, ‘Toward a Military Cyber Maturity Model’, Canberra: University of New South Wales Canberra

- Ormrod & Turnbull, 2015

- United Nations, 2005, p 7

- Austin, 2016