Abstract

This paper presents a template of what to do and how to think if you want to influence others to join you in tackling complex problems in conditions of uncertainty, ambiguity and risk.

It reports a study that (1) identifies what junior and mid-level military professionals perceive as being ‘good leadership’ from the perspective of followers, and (2) examines the evidence in favour of a leadership style that balances task and people requirements as the desired leadership mode within the military profession.

In-depth interviews were conducted with 67 professionals (officers, WO1 and 2, and NCO) to explore the features they used to differentiate between leaders who were effective or ineffective and appealing or unappealing. Six main factors–persona, proficiency, authenticity, purpose, people-orientation and process–were identified and proposed as the nucleus for an Army leadership model.

The paper concludes with some broad recommendations for expanding this initial foray into military leadership research into something more substantial and useful.

Introduction

The centrality of leadership

Leadership is the process of engaging others in concerted efforts to pursue a goal, in conditions of complexity and ambiguity or in anticipation of such conditions.

Time and again when it really counts–in the two world wars, in Korea, Malaya, Vietnam, in peacekeeping, in disaster relief, and currently in the longest war in its history–Australia’s military has demonstrated high standards of operational leadership at every level. Despite not having had serious ‘match practice’ for a quarter of a century, it was central to bringing peace to East Timor in 1999. And when confronted with damaging sexual harassment scandals in 2011, it responded promptly and systematically, in stark contrast to the evasive reactions of many other national institutions.

Given the centrality of leadership to so many spheres of its activities, you might expect the Australian military to have a keen analytical interest in the topic. But you’d be wrong. Beyond military histories and the occasional ‘this is how I did it’ memoir from retired generals, Australian contribution to the military leadership field has been sparse.1 And official doctrine is intriguingly uninformative regarding just what comprises the leadership process.2

This is in stark contrast to its equivalent institutions in the USA, which not only offer research opportunities to leading academics but also encourage serving officers to get involved in the analytical research process and then rotates them through its military academies and institutes of higher learning to ensure that lessons are translated into practice.3

Encouragingly, however, this may be about to change. The ADF is currently experimenting with a range of strategies, from training and education in ethics and leadership psychology through to 360° and 180° multi-rater evaluation and feedback, all aimed at lifting an already high standard even further.

This study was initiated on the basis that such initiatives would be significantly enhanced if the Army was more specific about what ‘leadership’ involves, and about how leaders at all levels should think about – as well as do – leadership.

Two basic questions and their guiding principles

Our voyage of exploration revolves around two sets of questions.

First, just what is ‘good leadership’? What do leaders need to do in order to generate inherent authority? And who decides what ‘good’ means? Should it be assessed essentially on the basis of effectiveness (the frequency with which a team completes its assigned tasks successfully), or are there additional and deeper criteria–such as morale, team development, versatility and resilience or simply the popularity/appeal of the leader in question–that should be taken into account?

Second, and allied to these, is it acceptable for a leader to focus routinely almost exclusively on tasks/outcomes, regardless of the effects on the people in the team? If the job gets done, does it matter if the people are burnt out in the process? Beyond operational exigencies, can this be justified as ‘normal’ practice? Or is a balanced task-people focus style likely to be at least as effective in mission achievement and superior in other ways?

The answers to the second set of questions essentially fall out from those to the first and by reference to the scholarly literature.

An important aspect of framing the study was the definition of the central concept of ‘leadership’. All interviewees were (commendably) able to give the definition from current doctrine, ie as a process of influencing people to pursue goals and find solutions to complex problems. (The scholarly literature uses much the same terms.) But the distinctive challenges associated with leading in the military institution demand attention to deeper aspects of the process and its intended outcomes.

One of the crucial things about military leadership is that it is generally performed in conditions of ambiguity, uncertainty and risk. Often the ‘right’ way forward is unclear, and leaders and followers alike will be understandably apprehensive about what lies ahead. Leaders who do best in these situations are those who had anticipated such challenges and had established strong levels of followership in advance. (Followership is the willingness and ability of an individual in a team to commit to its leader’s objectives, take direction willingly and constructively, get in line behind a program, be part of a team, and deliver on what is expected.)

Additionally, those who hold the sovereign’s commission have inherent officership obligations that go beyond simple short-term mission accomplishment. Military leaders should always be thinking about what they need to do now to create the right conditions for later.4 They should always lead ‘strategically’: not so much in the conventional sense of ‘big picture issues’ but rather in terms of always acting with the longer term in mind, including building human and social capital as investments for the future, for all those who will succeed them in command.

The significance of these concepts will become clear as our argument proceeds.

Method

The exploration of the nature of ‘good leadership’ was addressed empirically, by tapping the experiences of a sample of military professionals at the lower levels of the professional pyramid.

In-depth interviews were conducted with 27 JNCO, SNCO and WO1/2 and 40 officers (mostly majors) to explore the factors they used to differentiate between effective and ineffective leaders (ie achieved results–or did not) and appealing and unappealing leaders (ie were someone with which that person would–or would not–like to be associated in the future).

Each interviewee was asked to focus separately on pairs of effective, ineffective, appealing and unappealing bosses with whom they had served, and identify what each did in common that had contributed to their effectiveness/appeal. This method minimises the tendency to focus on ideal models or on attributes that are so distinctive that they are embodied in only a few people.

Most interviews were conducted face-to-face, and by phone with 19 others. Questionnaires were sent to interviewees beforehand for prior consideration, and transcripts were e-mailed to interviewees shortly afterwards to confirm their accuracy and comprehensiveness.

The responses were coded and categorised into factors that represent the distinctive sets of behaviour that military professionals look for and/or notice as being significant in the ‘leadership’ process. Instances of these were coded only once for each interviewee, regardless of the number of examples that he/she might have given about that factor. For example, an interviewee might have given three examples of, say, a leader’s interaction with team members but it was still coded once only under the relevant factor.

The utility and validity of the findings were judged from both practical and theoretical points of view. That is, they needed to make sense to Australian military professionals and be consistent with what the broader theoretical literature tells us are the dimensions of ‘positive leadership’.

What military professionals perceive as being ‘good leadership’

The elements of good leadership

Six factors were identified as being the core elements of leadership practice:

- Persona –look the part, act the part, be the part: reflect what is expected of an Australian military leader (in terms of character, demeanour, composure, confidence, approachability, professionalism and values);

- Proficiency –bring expertise and professional knowledge to the process: demonstrate problem-solving capacity and effective performance across a range of situations;

- Authenticity –be a leader for us: prioritise activities that advance the common good, as opposed to those that advance the leader’s personal career interests and make him/her look good;

- Purpose –focus and energise committed action: communicate a coherent path forward and a plan associated with that path;

- People-orientation –relate, develop, bring together, bring along: treat team members as valued colleagues, forge a sense of mutual trust and common identity and focus, and help them develop their skills and career opportunities; and

- Process –engage and stretch: engage team members collaboratively in working together and learning from experience.

Typical behaviours mentioned in both favourable and unfavourable terms for each factor are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Examples of component behaviours of each factor

| Attribute | Favourable examples mentioned | Unfavourable examples mentioned |

|

Persona |

Approachable but uncompromising in their expectations. Looked the part, in terms of punctuality, dress, demeanour, organisation and the occasional light touch. |

Falsely confident, arrogant and condescending. Indecisive, and often stuck in a search for ‘certainty’. |

|

Proficiency |

Showed intelligence and wisdom. Professional and performed always to their best. |

Not properly across their brief. Unable to see the bigger picture and where their activities fitted. |

|

Authenticity |

Driven–but for the common good, not for their personal advancement. Did the right thing, regardless of the personal consequences. |

Focused on their own image at the expense of the real goals. Blamed subordinates for mistakes, often without their knowledge. |

|

Purpose |

Articulated the goal and kept us on track, and didn’t allow the team to be diverted by extraneous needs. Great communication skills, with vivid language and engaging energy. |

Failed to provide clarity and direction. Too much time adhering to regulations and ‘ticking boxes’, as opposed to providing capability. |

|

People- orientation |

Rolled up their sleeves and joined in. Spent time coaching and mentoring. |

Rarely seen outside their offices. Questioning would be denigrated, even when they were intended for clarity. |

|

Process |

Gave people autonomy but were still clearly in charge of the overall effort. Lived and breathed mission command. |

Micromanagers. ‘My way or the highway’. |

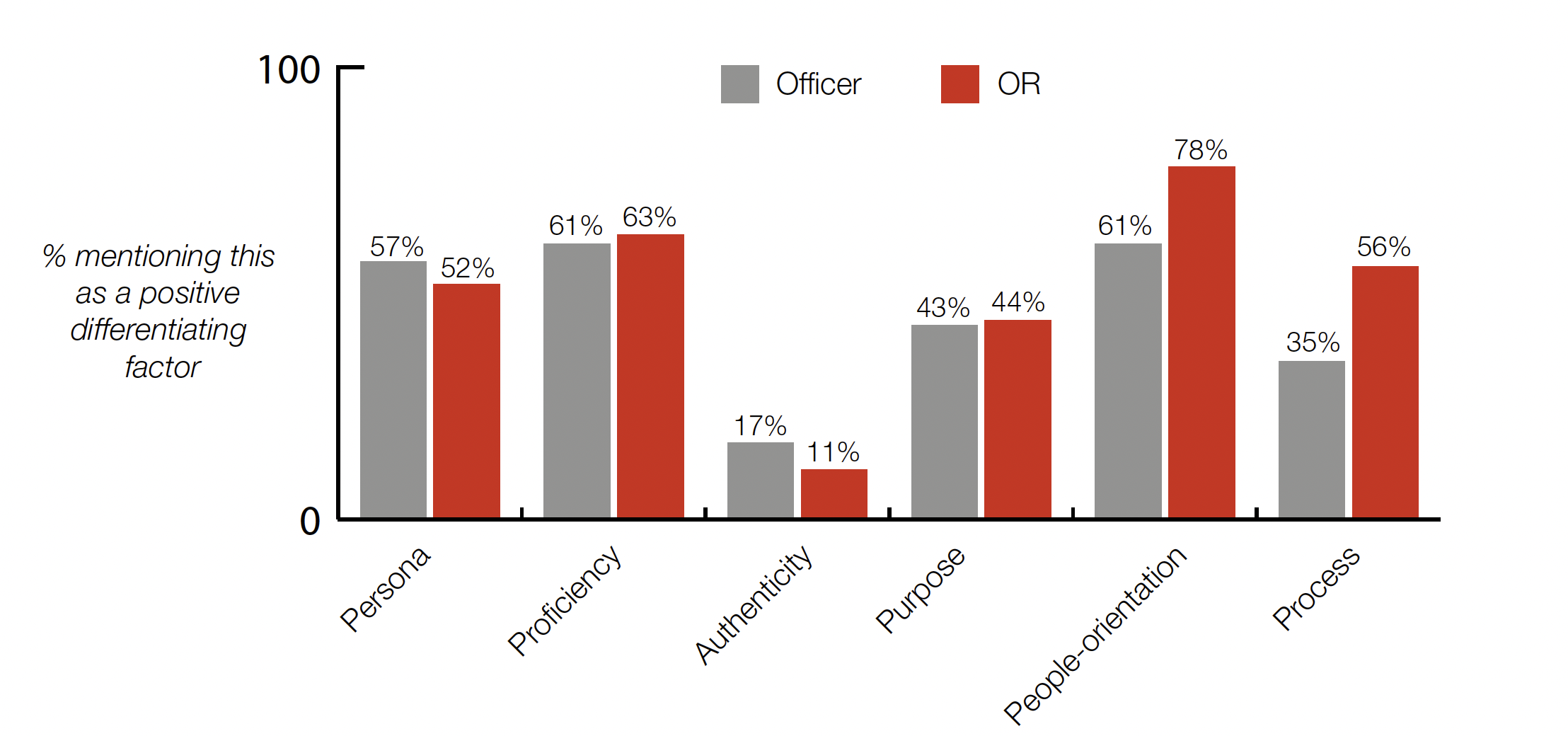

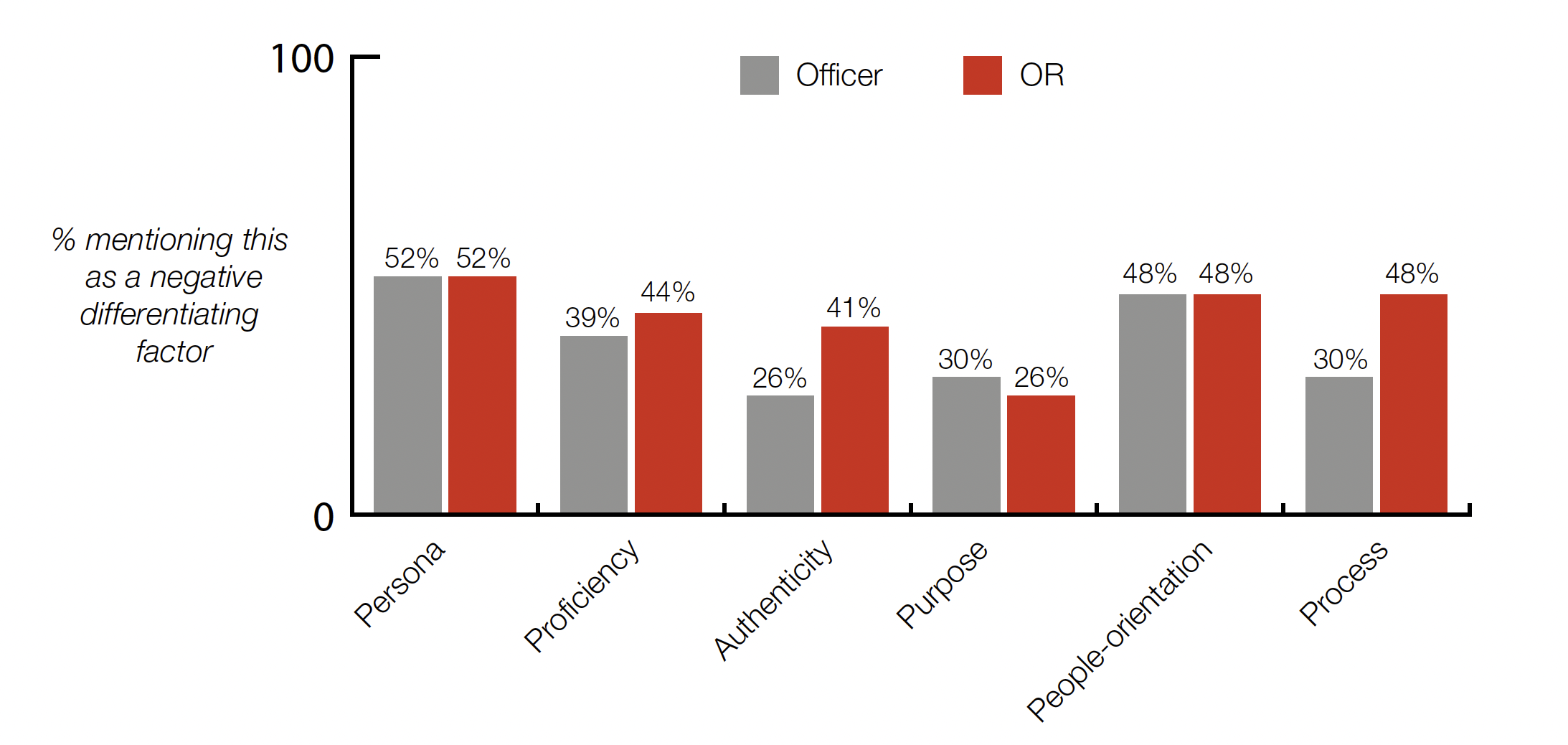

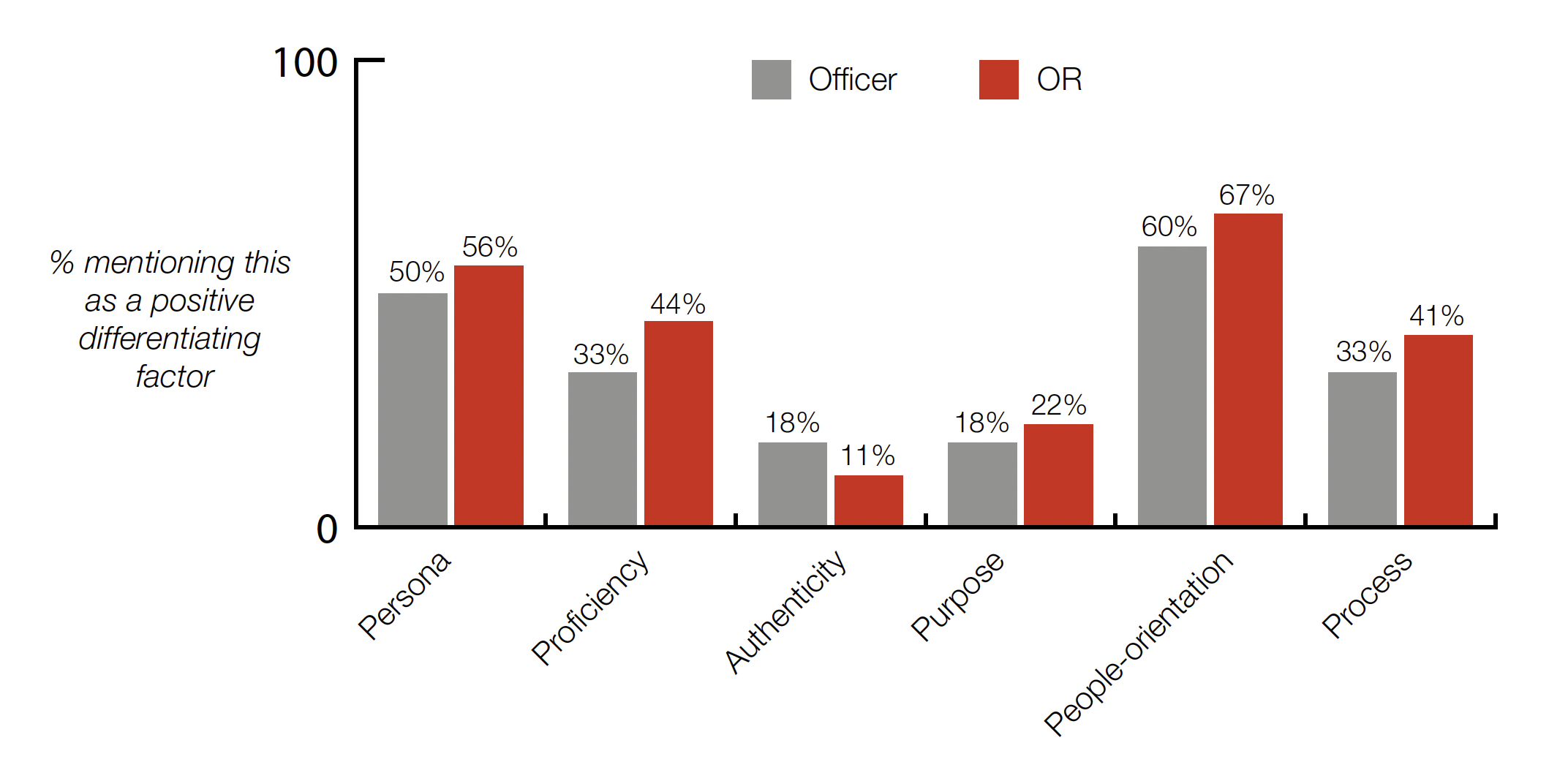

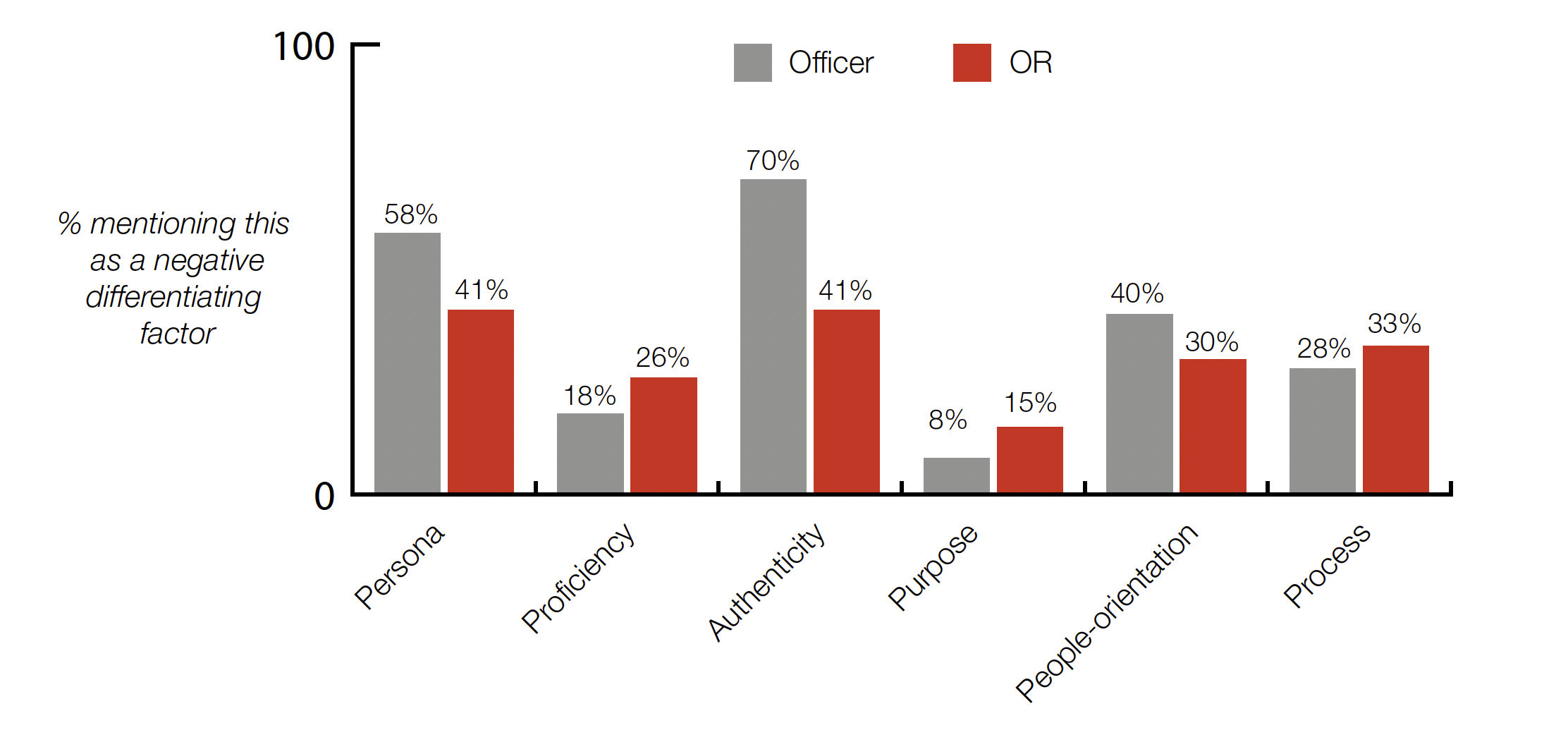

The frequencies with which the component behaviours of each of these factors were mentioned in interviews in conjunction with Effectiveness, Ineffectiveness, Appealing and Unappealing are shown in Figures 1, 2, 3 and 4 respectively.

Although certain factors stand out for both Effectiveness and Ineffectiveness, their spread is fairly even. That is, all factors contribute to perceptions of effectiveness or ineffectiveness.

This is somewhat less likely for Appealing and even less so for Unappealing, where three or four factors–Persona, People-orientation, Process, and particularly Authenticity–predominate.

Authenticity emerges as a factor that is more likely to be in the breach than in the observance. This may be indicative of professional values. People who value authenticity and integrity probably take it for granted in others unless there is clear evidence otherwise, in which case they will be particularly likely to notice its absence.

Figure 1: Differentiating factors in leadership that is seen as ‘effective’

Figure 2: Differentiating factors in leadership that is seen as ‘ineffective’

Figure 3: Differentiating factors in leadership seen as ‘appealing’

Figure 4: Differentiating factors in leadership seen as ‘unappealing’

These frequency distributions suggest that different personality types or styles are associated with effective/appealing leadership on the one hand and unappealing leadership on the other. The good leader is an all-rounder: professional, focused, and working with and through team members in the pursuit of relevant goals. And although interviewees were able to highlight specific aspects of leader behaviour, in all likelihood these merged into a near-seamless set of activities, most of which could have been categorised in several ways. For example, activities that were directly related to Process would have also served to demonstrate People-orientation, Persona, Authenticity and Proficiency, and would have been a reminder to followers of their Purpose.

On the unfavourable side, we find the self-centred and insecure me-firsters (‘SCIMFs’). The SCIMF is the epitome of toxic leadership. It is not surprising that SCIMFs are consistently seen as both ineffective and unappealing. Their priorities are often poorly aligned with the main game; they tend to exert an inappropriate level of control for the circumstances; they make little attempt to build relationships and therefore do not have the levels of emotional support and shared identity that more inclusive leaders can offer; and they deter team members from using their initiative. The argument that ‘it seems to work’ is not persuasive, given the lost opportunities for innovation and costs in terms of team development and morale. Moreover, SCIMF success may be due in large part not to so much to the leader but to the tendency for military teams to get on with the task regardless of the leadership style of its designated head. (This is one of the great strengths of Army leadership culture.) Even here, however, the effect will often be less than optimal.

These propositions regarding the influence of different personality types are necessarily tentative. The hypothesis can and should be tested using more rigorous methods.

The effects of good leadership

When asked how they felt when led by the effective leaders they had just described, interviewees used expressions that alluded to identification, trust and intrinsic satisfaction.

These included the following: ‘wanted to work with them’; ‘felt part of the team’; ‘wanted to be like them’; ‘felt valued’; ‘would have done anything for them’; ‘felt we could do anything together’; ‘felt part of a relaxed team atmosphere, as opposed to “just doing a job”’; ‘motivated me to emulate their way of doing things in respect to team management, such as mentoring and facilitating as opposed to “exercising authority”’; and ‘felt confident that he would watch my back and generally look out for me’.

As a major remarked:

It’s the people who get work done, and you must manage them in such a way as to generate loyalty because, if it is not there, they might happily and diligently work for you from 8 to 4 but they won’t work to levels beyond expectations.

One sergeant spoke of how his career motivation had been wavering but how this changed when he was assigned to the team of a particular leader who ‘confirmed my career choice, and confirmed that it would be worthwhile for me to use my abilities to contribute to the Army’.

A junior officer spoke of how, even though being led by a particular person was ‘challenging and sometimes frustrating’, it ‘made me feel incredibly proud’.

Finally, the essence of this kind of leadership was summed up by a corporal who remarked that ‘just a little bit of this makes you feel warm and fuzzy, and is enough to keep you working your guts out’.

Validity of the findings

The validity of these findings can be judged by the extent to which they make sense and are consistent with mainstream academic leadership models.

The findings pass muster on both accounts.

Military professionals to whom these findings have been shown identified immediately with these factors as descriptions of leadership. They are also consistent with research on leadership in the Australian context.5 Australians respond best to supportive, egalitarian and ‘no BS’ leadership; we don’t mind authoritative leadership but we tolerate it more readily when we believe that the authority appreciates our perspective and will act in our interests.

On the academic side, the six factors align with the main dimensions of mainstream positive leadership models. These include ‘transformational leadership’ (the most systematically researched theoretical leadership model in the last three decades) and the complementary concepts of ‘authentic leadership’ and ‘servant leadership’. Transformational leadership inspires followers to raise their sights and lift their performance to levels beyond normal expectations, and to identify with and want to emulate the leader in question. In contrast, ‘transactional’ leaders control behaviour by incentives (‘you do this for me and I’ll do this for you’), corrections and reinforcing good performance.6 Authentic leadership is similar to transformational leadership but with specific emphasis on the ethics and values that guide priorities and actions, in the sense of their being focused on the common good.7 And servant leadership is similar again, but with specific emphasis on ‘prioritising the fulfilment of team member needs’.8

Table 2 compares our six factors of military leadership with the four dimensions of transformational leadership. It can be seen that there is a close correspondence between the twin conceptualisations, except in one respect.

The one divergence between the two conceptualisations is in terms of the first factor. Whereas the Idealised Influence dimension of transformational leadership sees character, competence and values as a single factor, our leadership model represents this aspect of leadership by the three separate factors of Persona, Proficiency and Authenticity.

There were two main reasons for separating them in this way:

- Practical. It was evident from talking to many contemporary military professionals that each of these factors contributes separately to the overall effect of belief and trust. A leader could be strong on one or two and weak on another. For example, interviewees frequently spoke of leaders who were unpleasant and abrasive but who were nevertheless trusted because they were very proficient professionally.

- Conceptual. History is replete with leaders who were driven by questionable levels of morality but whose charisma was such as to compel strong levels of followership, eg Hitler and Stalin. The Army leadership model avoids this discrepancy.

Table 2: Categories of Australian Army leadership behaviour, their transformational leadership equivalents and their psychological effects

| Category | Transformational Leadership equivalent: dimension and its behavioural essence | Psychological effect | |

| Persona, Proficiency, Authenticity | Idealised Influence | Acting in ways that inspire emulation of performance and values | Belief and trust in the leader |

| Purpose | Inspirational Motivation |

Setting a purpose that focuses, binds and energises by its relevance and challenge |

Confidence in (and potentially inspiration from) the designated direction |

| People- orientation | Individualised Consideration | Building social bonds that enhance self- esteem, self-confidence and teamwork | Belief in oneself and in the team |

| Process | Intellectual Stimulation | Engaging followers collaboratively | Fulfilment from the process |

Leadership effect and style

These findings bring us to the second set of questions that drove this study, ie whether it is acceptable or desirable for leaders to focus entirely on tasks/ outcomes, regardless of the effect on team members, as long as the job gets done.

There are three main reasons why the answer is ‘no’.

Firstly, as noted above, as clearly indicated by the findings of this study, Australians respond better to engaging and egalitarian leadership than to autocratic leadership.9 And while Australian leaders can achieve basic and minimal results with directive leadership styles, they need to do better than this if they want to achieve higher standards consistently.

In the business literature, this is called ‘the Apple paradox’. This refers to the apparent contradiction between the enormous success of the Apple Corporation and the hard-driving, arrogant and get-things-done-at-all-costs style of CEO Steve Jobs. It is instructive that, near the end of his life, Jobs agreed with his biographer that ‘The nasty edge to his personality was not necessary. It hindered him more than it helped him’.10

Secondly, military operations have long passed the era in which General John Monash could describe a ‘perfectly perfected battle plan as like nothing so much as a score for an orchestral composition’.11 Instead–to continue the musical analogy–contemporary military teams are much more like ‘jazz musicians who interact with each other on the basis of each person’s role in the group, guided by the structure of specific musical rules and norms’.12 Leaders in the era of the strategic junior leader need to act as catalysts rather than as controllers, and lead in ways that give optimal flexibility and autonomy, and make their junior colleagues collaborators in the process.13 However hard-driving this might be in practice, such leadership is unlikely to be seen as either ‘hard’ or ‘inflexible’ by those most affected, particularly if the need for hard-driving is explained in terms of mission accomplishment–and especially if those leaders have made the effort to build trust and set up the conditions for success in the relatively easy times before the stress of intensive operations.

This links with the third reason, and returns us to the fundamental principle of officership. Whatever their level, military leaders should strive to achieve more than the bare minimum, and should always have the longer term in mind so that they hand on teams that are in better shape than when they themselves took them over. These obligations of ‘stewardship’ also mean attending to the welfare of their charges.14

Not surprisingly, much of the research that confirms this principle comes from the military. For example, a very large study in the US Army showed that platoon performance in operational simulations at joint training centres was closely correlated to the pre-simulation in-garrison leadership styles of platoon commanders.15 The teams of those who led in ways consistent with our Army leadership model consistently achieved superior performance down the track. Similar effects were found in a study conducted in the Israeli Defence Force.16 Such leadership is crucial for outcomes beyond team performance and task achievement, including adaptability, cooperation, learning, resilience, employee well-being and turnover, and service spirit and citizenship.17

Given that all the evidence points clearly to the superiority of the leadership styles described in this paper, why do some leaders continue to practise an essentially autocratic and task-oriented style?

There are at least three main reasons.

Most simply, and as already discussed, many officers are neither aware of nor interested in the academic literature. Moreover, many may have inadvertently modelled themselves on task-oriented leaders with whom they had close contact early in their careers. (Early career role models exert a disproportionate influence over long-term behaviour.18)

Secondly, a task-oriented style is often more ‘efficient’ in the short-term. Time with subordinates means time spent away from the in-tray dealing with the multitude of often comparatively minor tasks that make up a large part of a busy officer’s routine. Since advancement depends on satisfying the requirements of one’s superior, it is not surprising that career-oriented officers often give short-term priority to activities that meet their superiors’ most measurable requirements.19

The final reason has deeper cultural roots. Many managers continue to believe that strong task orientation is more likely to contribute to superior performance. A recent study showed that such a tendency is particularly prevalent in organisations with predominantly male workforces and corporate purposes that were predominantly pragmatic and action-oriented (‘real men are tough leaders’).20 Regardless of their erroneous nature, such assumptions can be very difficult to shake off, particularly in the light of the weight given to particular leadership styles in selection decisions, and the mental models and expectations that are passed from generation to generation. Plainly, it’s a proposition that deserves deep reflection at all levels of the military profession.

Limitations of the study

Interesting and useful though the finding might be, the study has two major limitations. Firstly, the sample is under-represented in junior officers, whose perspectives may well be subtly but significantly different to those with an extra decade or so of service. Secondly, the results tell us nothing about current standards of leadership practice in the Army.

The frequency with which the behaviours associated with a particular factor in the model were mentioned are a measure of what people look for and notice about ‘good’ leaders, regardless of how we designate ‘good’. And although such frequencies do not necessarily indicate the relative importance of particular factors, they obviously have some correlation.

Thus the frequency count for a factor represents a broad indication of its importance within the overall leadership process. But it is literally that–no more than ‘broad’. Each of the factors plays an important part in the total process. And the precise actions needed to perform each of the factors will depend on the circumstances.

The next step in investigating the general issues that gave rise to this short study should therefore be to broaden the sample and use more systematic measures of leadership performance. These should include longitudinal designs, in order to analyse questions such as the longer-term effects of leadership as it might be practised during exercise simulations and on operations. This would also facilitate the investigation of potential intra- professional stylistic differences, eg between GSO and SSO, female and male officers and NCO, and other demographic variables of interest.

It is to be hoped that the Australian military institution will shrug off its traditional indifference to scholarly analysis and throw itself into a long overdue investment in self-analysis, self-understanding and self-improvement.

Conclusions

The findings of this study represent the first systematic first-principles analysis of desirable leadership models in the Australian Army. It goes considerably beyond previous offerings, such as the Adair situational approach to leadership and the principles of leadership enunciated in LWD 0-2.21

In terms of the first question investigated in the study–the nature of ‘good’ leadership–the Army leadership model derived in this study presents a template of how to behave if you want to lead effectively. Collectively or individually, it can be used as a guide for professional development and for day-to-day leadership behaviour.

In terms of the second question investigated in the study–the pros and cons of task-oriented leadership–it is telling that the most frequently mentioned behaviours were associated with ‘People-orientation’. This was particularly the case for soldiers.

The findings confirm the Army’s traditional emphasis on developing ‘all- rounder’ professional leaders of character, whose priorities are for the mission and the team before themselves. Good leadership is balanced across all the factors, giving as much attention to people factors as to task factors.

An all-round leadership style has always been important for the Australian military but it is even more important in the era of fourth generation warfare and the strategic junior leader, in which leaders must see themselves as catalysts rather than as controllers, and as stewards as well as commanders. While ‘leading from the front’ remains crucial, particularly in terms of winning trust and establishing standards, the concept must not be interpreted too literally. Given the fluid nature of the operational context, and the high levels of skill and motivation that even those at the most junior levels can bring to bear, a leader’s responsibilities must include doing what is necessary to help each team member to contribute optimally to mission success. And the establishment of capability, solidarity and trust established in the easy times must be seen as an investment for when things become more challenging, and as part of the obligation that each officer has to the institution.

The principle of ‘leading today with tomorrow in mind’ may well be a crucial differentiator between being good and being great. Meeting the significant challenges of the future will require the Australian military institution to give as much attention to thinking about leadership – at the institutional as well as the individual level, and at the academic as well as the practical level – as it currently does to doing it.

Endnotes

- This lack of intellectual curiosity has long been a feature of the Australian military institution, as noted recently by other scholars such as James Brown (Fifty Shades of Grey: Officer Culture in the Australian Army, Australian Army Journal, 2013, X, 3, 244-254) and William Westerman (Learning the Hard Way: Developing Australian Infantry Battalion Commanders during the First World War, Australian Army Journal, 2016, XIII, 1, 52–67).

- Australian Army, Land Warfare Doctrine, LWD 0-2, 2013.

- See for example the many studies done by former Colonel Sean Hannah and his colleagues, eg. Sean Hannah, Mary Uhl-Bien, Bruce Avolio, and F. L. Cavarretta, A framework for examining leadership in extreme contexts, Leadership Quarterly, 2009, 20, 897–919.

- Patrick Mileham, “Fit and proper persons”: officership revisited, Sandhurst Occasional Papers No. 10, 2012.

- Kelly Fisher, Kate Hutchings, and James Sarros, The “bright” and “shadow” aspects of in extremis leadership, Military Psychology, 2010, 22, S89–S116; Geoff Aigner & Liz Skelton, The Australian Leadership Paradox: What It Takes to Lead in the Lucky Country, Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2013.

- Bernard Bass, Bruce Avolio, Dong Jung, & Yair Berson, Predicting unit performance by assessing transformational and transactional leadership, Journal of Applied Psychology, 2003, 88 (2), 207–218.

- Bruce J., Avolio, Fred O. Walumbwa, and Todd J. Weber, Leadership: Current theories, research, and future directions, Annual Review of Psychology, 2009, 60, 421–449.

- Robert Liden, S. J. Wayne, C. Liao, and J. D. Meuser, Servant leadership and serving culture: Influence on individual and unit performance, Academy of Management Journal, 2014, 57(5), 1434–1452.

- Geoff Aigner & Liz Skelton, The Australian Leadership Paradox: What It Takes to Lead in the Lucky Country, Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2013.

- W. Isaacson, Steve Jobs, 2011, New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, p. 565.

- https://www.awm.gov.au/journal/j34/armybiog.asp.

- Benjamin Baran & Cliff Scott, Organizing ambiguity: A grounded theory of leadership and sense-making within dangerous contexts, Military Psychology, 2010, 22, S42-S62.

- Sean T. Hannah, John T. Eggers, & Peter L Jennings, Complex adaptive leadership: Defining what constitutes effective leadership for complex organizational contexts, in The Knowledge-Driven Corporation – Complex Creative Destruction, 2008, 79–124.

- Nicholas Jans, with Stephen Mugford, Jamie Cullens and Judy Frazer- Jans, The Chiefs: A study of strategic leadership, Australian Defence College, 2013.

- Bass et al, op cit.

- Taly Dvir, Dov Eden, Bruce Avolio, and Boas Shamir, Impact of transformational leadership on follower development and performance: A field experiment, Academy of Management Journal, 2002, 45(4), 735–744.

- C. S. Burke, D. E, Sims, E. H. Lazzara, & E. Salas, Trust in leadership: A multi-level review and integration, The Leadership Quarterly, 2007, 18(6), 606–632.

- David Day, Leadership development: a review in context, Leadership Quarterly, 2001, 11(4), 581–613.

- This is discussed in a recent blog on the website themilitaryleader.com (why do toxic leaders keep getting promoted?).

- L. Gartzia and J. Baniandrés, Are people-oriented leaders perceived as less effective in task performance? Surprising results from two experimental studies, Journal of Business Research, 2016, 69(2), pp. 508–516.

- John Adair, Leadership and motivation: the fifty-fifty rule and the eight key principles of motivating others, Kogan Page Publishers, 2006; LWD 0-2, 2013.