Abstract

Extremism poses a danger to any society and can be detrimental if unchecked. In the post-web era, extremist groups have started using information networks to influence public perception, gain silent sympathisers, and radicalize youth. One such group–the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS)–deftly uses information networks to intimidate rival groups, terrorize populations, radicalize youth, and recruit foreign fighters from Western countries—thus posing a threat to the security of regions in which it operates and in which it has supporters. This research study has developed a framework to analyse the content produced by ISIS and proposes a pseudocode designed to enable agile and responsive information operations. This framework is based on four elements: (1) qualitative and (2) quantitative properties of information, (3) affective and emotional dimensions, and (4) contextual factors. It was found that ISIS’s information strategy is multi- tiered and designed to adapt to the affordances of digital media. ISIS’s content is rich in affective and emotional cues, religiously-significant terms, and a romanticized view of martyrdom and the caliphate. Their content also uses highly negative and positive information bias (skewness) to demonize enemies and legitimize ISIS’s agenda respectively. It is hoped that the proposed framework along with the pseudocode and findings of this study will enable the security agencies to develop a counter-informational response.

Introduction

The battlespace of the twenty-first century is networked and occupied by densely-populated, highly-connected communities. Social media can be weaponised to support influence operations; in turn, the ways in which hostile actors undertake information operations can provide insights into their own strategic objectives and organizational structures. In this paper, we investigate what the analysis of web and social media content can tell us about how insurgent groups influence the perception of the local populations. The implications are significant in that populations connected to social media form an intimate component of the landscape in which the profession of arms applies kinetic power.

Major Sarah Isdale1 writes: ‘Tactical cyberspace control is rapidly becoming central to dominating the information environment and thus will emerge as paramount for forces campaigning in the information age’. Innovation in this area has been discussed extensively within Army circles over the past two years. David Kilcullen’s discussion paper2–The Australian Army in the urban, networked littoral–highlights the significance of connectivity on conflict. Last year Dr Glenn Russell’s3 contribution to the Land Power Forum blog noted: ‘Monitoring the social media arena and cultivating the skills needed to compete therein are sure to prove key during future challenges to Australia’s national security’. This paper offers insights to inform innovative thinking around influence operations and intelligence assessments in the twenty-first century battlespace.

The Australian Army’s Future Land Warfare Report acknowledges this trend and notes that information networks will be used by non-state actors to influence public perception.4 The purpose of this research is to analyse the web-based informational content produced by The Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS), with the objective of: identifying (1) the informational properties of; and (2) information strategies used in their content and to develop: (3) a framework guiding the Australian Army in identifying the extent of threat present; and (4) a pseudocode operationalizing the framework. To achieve the objectives of this research, different properties of information (including qualitative and quantitative) provided a lens through which ISIS’s media content was analysed. This lens also helped to develop the pseudocode systematizing the identification of extremist informational cues in ISIS’s content.

ISIS, a group that appeared on the global scene in 20145, is deftly using information networks to spread its totalitarian agenda and poses a threat to the national security of many nations. More alarmingly for Western nations is the group’s use of social media and online networks to recruit fighters from different countries and to gain silent sympathisers; social media can be weaponised to support influence operations. This paper is organised as follows: the significance of this work is presented; followed by a description of the literature review and of methodology; next, data analysis and results are discussed; and finally, conclusions are provided.

Significance of this Research

The use of information networks by extremist groups to spread their message and to cause cyber and/or physical damage has drawn the attention of various researchers. Some for instance noted that lone wolves, insurgents and hacktivists can use information networks for launching cyber attacks.6,7 Similarly, Adaptive Campaigning – Army’s Future Land Operating Concept8 made a note of increased misuse of informational terrain by extremists to seek shelter and cause harm. This strand of research (eg Arquilla; Arquilla et al; and Future Land Operating Concept) on the use of information networks by adversaries provides valuable insights about the use of information content; however, it does not tell us about the nature of information properties underlying each kind of content. It is important to know the properties of information as a change in content brings a change in information distribution, with resulting impacts on individual perception9. This research examines not only the content but also identifies the distributional properties of information relating to the different content and media in web-based extremist messaging. The findings of this research will help the Australian Army to: (1) better understand the role of distributional properties of information in shaping an informational message; (2) assess the information gathered to identify the potential threats both from home- grown as well as foreign extremist groups; and to (3) develop counter informational strategies.

Literature Review

Extreme–as a term–refers to something far from moderate10. According to Sotlar11, ‘...extremism is essentially a political term which determines those activities that are not morally, ideologically or politically in accordance with written (legal and constitutional) and non-written norms of the state; that are fully intolerant toward others...’. People with extremist views are generally intolerant of anything, either in practice or thinking, which is different from their own views12. Extremist groups are present in almost every part of our world; however, their ability to disseminate information and influence public perception has increased tremendously in the post-Internet era. Corroborating this assertion, the New York Times published an article, ‘The revolution will be posted’, discussing how blogs transformed the 2004 USA presidential race13. In a similar vein, Eltantawy and Wiest14 argued that social media played an instrumental role in the Egyptian revolution. The role of online media, including YouTube, Twitter, e-mail, Facebook etc, in facilitating extremist groups and non-state actors has also been recognized by national security agencies. For example, the Future Land Warfare report by the Australian Army15 noted that some people or groups will use information networks to influence public perception. This observation can now easily be attested by looking at the recent online media use by extremist groups.

One such group is ISIS, appeared on the global scene in 201416 and: (1) occupying areas in Iraq and Syria; (2) using information networks, especially social media, to advance its agenda; (3) carrying out atrocities against minorities and opposing forces; and (4) recruiting foreign fighters from Western countries. According to Neumann, the total number of foreign fighters in the Syria-Iraq conflict exceeds 20,000 and almost 4,000 of them are from Western countries17. For instance, it is estimated that approximately 100–250 from Australia and 100 from the USA18, 150 from Netherlands19, 100 from Canada20, 677 from Germany21, 900 from France, and 500 from Britain22 have travelled to Iraq and Syria to join ISIS.

In addition to the recruitment of foreign fighters, another significant and concerning factor is the radicalization of young people living in Western countries. Some security officials, including the former deputy director of CIA, commented that ‘...ISIS poses a threat to the homeland. That threat is largely indirect and involves ISIS’s ability to radicalize young Americans to conduct attacks here’23. This threat of radicalization is noted in a large number of research studies on foreign fighters, ISIS, and its media strategy. For example, in a study on foreign fighters from Netherlands, Bakker and Grol examined six cases of potential foreign fighters noting that extremist narratives did play a role in radicalization. However, they also noted the role of social and personal factors in radicalization24. Mueller and Stewart analysed 61 cases of extremism in the US and found that ‘the people in many of the cases did go to the Internet for further information, and they frequently sought out the most radical sites...’25. Like Bakker and Grol however, Mueller and Stewart also noted the presence of various other factors (eg personal identity crises, difficulty holding jobs, criminal records) that potentially also played a role in radicalization. Porter and Kebbell26 looked at the radicalization of 21 individuals convicted in Australia for terrorism, analysing law reports and related newspaper articles concerning these individuals. The authors noted the interplay of different factors including identity issues, flawed understanding, and exposure to extremist content contributing to radicalization.

In view of the role of extremist content in radicalization, it is important to understand the informational properties of such content and the impact these properties leave on individual perception. Information has both qualitative and quantitative properties. For assessing qualitative properties of information, works of Lee et al, and Knight and Burn, provide important directions. Lee et al developed an instrument that conceptualized and operationalized 15 dimensions of information quality27 while Knight and Burn described various information quality frameworks and then identified 20 common dimensions of information quality including properties such as accuracy, consistency, security, and timeliness28.

Excess and scarcity of information are related with quantitative aspects and have been researched more in the areas of finance, economics, and marketing. For example, impact of incomplete information on insider gains29, impact of excessive positive clues on product valuation30, and the role of quality and quantity of information in decision-making represent research on quantitative properties of information31. The quantitative property of information used in this study to analyse ISIS’s content was skewness. From a statistical viewpoint, skewness denotes a distribution which is highly imbalanced32. As a distribution is around a mean, therefore this imbalance can be in either direction, leading to a positively- or negatively- skewed distribution. This characteristic of distribution can be applied to the distribution of information too. According to Afzal33, a deliberate attempt can be made to release information which has overly positive connotations, thus positively skewing information and vice versa.

Methodology

The research problem in this project is addressed using content analysis. Content analysis was done to: (1) identify themes in the data; (2) assess qualitative properties of information; and (3) prepare corpus of data for the assessment of quantitative properties. Qualitative attributes (eg balanced, accurate, consistent) of the selected information were assessed based on the works of Knight and Burn and Lee et al34. Definitions of qualitative attributes, provided in Knight and Burn, were used to contextualize the assessment appropriately35. Quantitative properties of skewness and lexical diversity were also assessed. According to McCarthy and Jarvis, ‘lexical diversity refers to the range of different words used in a text, with a greater range indicating a higher diversity’36. Lexical diversity was assessed by calculating a Standardized Type Token Ratio (STTR). Specifically, content was divided into paragraphs of 200 words each**2 and then the STTR was calculated for every paragraph. To calculate skewness, two steps were taken: (1) specific recurring terms occurring in the content were identified and a repository of terms was created; (2) synonyms for every term were identified and then also added in the repository; and (3) based on theological, political, historical, and affective/emotional relevance, skewness weight was assigned to each term.

To draw out themes and findings that can be applied across extremist use of social media we also explored online content from another extremist US militia group called ‘The Three Percenters’ in order to provide some comparison. The Three Percenters are a so-called patriot movement and a paramilitary group that pledges armed resistance against attempts to restrict private gun ownership, and depict the federal government as tyrannical37. In part, the selection of the Three Percenters was opportune; as we began to undertake the process of data collection, various factions of the Three Percenters militia became embroiled in the armed stand-off at Malheur nature reserve in Oregon38. As we harvested data from across the social media platforms of ISIS official and supporter networks, the Oregon stand- off generated a rich dataset from the militia movement in the USA.

Using an initial subset of social media users clearly aligned to extremist groups, the researchers adapted the relational functionality (‘is friends with…’, ‘follows’, ‘links to…’) of these social media profiles to derive a dataset of cross-platform social media content. This approach was adopted to provide comparative findings based on commonalities and differences between the content of ISIS and the Three Percenters. Please see appendix for analysis.

Discussion

ISIS’s content includes a large number of terms signifying religious/theological factors, at times carefully contextualized using historical information but, more importantly, these terms are unpacked for readers using out-of-context and flawed interpretations. The rhetoric of ISIS is also full of terms with strong affective and emotional connotations. It is important to note that this group’s skilful twisting of religious, historical and political factors, along with emotional and affective appeals, presents an informational message that has considerable appeal. Specifically, religiously-significant terms such as ‘taghut’, ‘murtaddin’, ‘apostates’ ‘shahada’ have been used repeatedly to label others as ‘enemies’ and a threat to their desire to establish an idealistic state of caliphate (khilafah). Similarly, terms with affective connotations, including ‘angry’, ‘grieve’, ‘fear’ ‘love’, ‘suffer’, are used to: (1) gain sympathies and legitimacy for ISIS; and (2) present groups with which it is in conflict as ‘the other’. For example, in the ‘foreword’ of Dabiq’s issue no. 14 a very explicit rhetorical warning was given to opponents of ISIS:

‘Having heeded the lessons of years spent fighting the harshest of wars...soldiers of the Islamic State promise their adversaries dark days of death and destruction in their own land. Bullets and shrapnel will slash and pierce...Survivors will be scarred...physically and mentally, haunted whenever their eyes are closed ***...”39.

Addressing scholars who give verdicts against ISIS, it was stated in Dabiq’s issue no. 13:

‘Indeed, it was already obligatory to spill the blood of these scholars, for they had apostatized years ago, defending and supporting the taghut in the war...’40.

In a similar vein, derogating scholars who are balanced in their approach, issue no. 14 states:

‘The kufr of liberalism and democracy was instilled and a new breed of “scholars” was born, becoming a part of the West’s very own imams of kufr’41.

An important aspect of ISIS’s strategy are the insertions of: (1) verses from religious texts; (2) opinions of scholars; and (3) a romanticized view of martyrdom at various crucial places in the content to provide a seemingly authentic, balanced and yet emotionally-laden message to readers. This message presents a stimulus for the perception of potential receivers. Russell noted that people’s perception is influenced by external stimulus and depending on the ways people perceive the stimulus [including informational content] can have an affective impact42. Affect can then influence perception, cognition, and behaviour of people43.

This content can appeal to minds not grounded in basic religious knowledge or those looking for escape from existing personal issues. Researchers examining the lives of foreign fighters have identified personal issues (eg poor performance at school/university, family breakdown, criminal record) as an important commonality in a large number of departees. For example, 66% of departees from Germany had criminal records44, whereas the majority of Dutch foreign fighters also had varied personal issues such as criminal records, family problems, unemployment45. Hall in 2015 profiled Canadian foreign fighters and noted that ‘the typical foreign fighter joining ISIS also seems to be lost at a transitional stage in his life.’46

An important part of this research was to analyse the lexical variety of ISIS’s content. For this purpose, STTR was calculated for a selection of content from Dabiq. The lexical variety of the analysed content in Dabiq is reflective of ISIS’s agenda; that is, to gain attention and sympathy. The STTR of content did remain below 60%—a mark representing low lexical diversity and therefore considered useful for easy comprehension by the contents’ audience. However, this finding should be taken with caution as the data under analysis was limited only to Dabiq and did not include other sources of ISIS’s content.

ISIS is weaponising information by using positively- and negatively-skewed narratives to advance its cause. It is apparent that ISIS employs positive skewness, especially in describing its combat and violence. A particular use of this strategy is also highly visible in information content presenting: (1) an idealistic view of caliphate; and (2) martyrdom. Negative skewness is used to label everyone as an enemy or a serious threat to ISIS and hence to the idealistic-and-to-be caliphate. ISIS includes countries, rival groups, alternative perspectives, and even individuals, in its list of enemies.

It is significant to note that the ISIS’s propaganda is designed to serve multiple purposes, including terrifying local populations, intimidating rival groups, influencing public perception and gaining silent sympathizers—some of whom then may decide to join ISIS in fighting. The brutality of the imagery presented in ISIS’s official and supporter social media channels is also notable. This is strategically-framed psychological warfare via social media that coincides action with narrative to maximize effect47.

It is highly important for soldiers to comprehend the significance of terms, different ways in which these terms can be used–as well as consequent affective evocations, because these evocations can lead to actual action. Such knowledge is also important from an operational standpoint especially when soldiers are in active combat zones and engaging regularly with civilian populations. Countering combat strategy and informational propaganda of groups such as ISIS requires a deep understanding of religious and political sensitivities—once such a group is uprooted there should be denial of any sprouting of splinter groups or emergence of new groups of similar nature. From a strategic standpoint, understanding informational propaganda can help soldiers to develop counter-narratives and to build a positive image with civilian populations—all of which will help protect soldiers from the numerous threats present in active combat zones. There are also implications for developing an information strategy to be used in connected online environments. Army has to engage not only in physical space but also in virtual space as combative operations now include the cyber domain. The findings of this research can be used in assessing the extent of affective, religious/theological, and political, cues present in informational messages along with possible impacts on public perception.

Conclusion

This study has developed a framework to analyse the content produced by extremist groups, based on four elements: (1) qualitative; (2) quantitative properties of information; (3) affective and emotional properties; and (4) contextual factors, including politics, history and religion. Based on this framework, content produced by ISIS in different formats was analysed to clarify its information strategy. Additionally, the STTR was calculated to assess the lexical diversity of ISIS’s content. A pseudocode was also developed to operationalize the framework. Finally, to broaden the scope of this analysis, content from another–yet very different–extremist group (the Three Percenters), was also examined. Some commonalities were identified including the use of symbolic imagery, narrative style and emphasising a sense of grievance. It is clear that ISIS’s information strategy is to produce and disseminate content through different media outlets and to influence different audiences. ISIS’s content contains carefully-chosen informational cues aiming to present a romanticized view of the caliphate, a highly- positively skewed portrayal of combat success, of the camaraderie of a military brotherhood and of death in battle as the ultimate sacrifice.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank reviewers for providing us with valuable feedback. We are grateful to Neil Churches for copy editing. Sabih-ur-Rehman and Shoaib Tufail also provided valuable research assistance.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Australian Department of Defence received by Dr. Waseem Afzal.

Appendix: Analysis

An important challenge in this analysis was to identify official ISIS-generated content. ISIS-related content has been disseminated through various media outlets including Twitter, YouTube and blogs. Researchers eg Gambhir48 and Steindal49 have identified ‘Dabiq’ as the official magazine of ISIS. Late issues of Dabiq (issue no. 13 and 14)50 and five news bulletins of ISIS51 (March 7–March 9; April 19–20, 2016) were content-analysed; there are repetitive sections from one issue to another including ‘foreword’, ‘military reports/operations’, ‘interview’, ‘from the pages of history’. Dabiq uses clear language to present the content; the quality of arguments is impressive based on historical, political and theological underpinnings and affective undertones are pervasive and skilfully used throughout.

Selected sections from these issues were analysed to identify major themes and important terms; based on theological/religious, historical and political dimensions. Some terms were identified based on their function to describe an event, qualify an action, and usually including an affective component. The work of Ortony et al was used to identify terms with affective and emotional connotations who examined approximately 500 words from the literature on emotions to develop a taxonomy of affective lexicon52. In the current study, a total of 479 terms were identified and then classified into one of the three categories.

| Terms Theological/Religious | Emotional/Affective | Political/Historical | |

| 1 | Khilafah | Grieve | Wakeup |

| 2 | Hijrah | Love | National interest |

| 3 | Bay’ah | Angry | Royals |

| 4 | Shahadah | Terrorizing | Stooges |

| 5 | Ummah | Mock | Taghut |

| 6 | Murtaddin | Shamelessly | Saudi |

| 7 | Mushrikin | Desperate | Palace |

| 8 | Shirk | Aggressors | Crusaders |

| 9 | Taghut | Defiantly | Masters |

| 10 | Jahannam | Angry | Liberalism |

| 11 | Kuffar | Bitter | Democracy |

| 12 | Jihad | Fear | Constitution |

Table 1. Classification of Terms

A skewness value ranging from 0 to 1 was assigned to each term classified in any of the three categories. This assignment was based on the following principle: any term signifying the (1) exclusion of someone from religion; (2) absence of faith; (3) presence of a fatal challenge to an idealistic state; (4) glorification of an action; (5) belongingness of a person; (6) emotional and affective appeals (eg anger, pleasure) was assigned a value (see Table 2). A term having a moderate connotation pertaining to any six dimensions mentioned above was given a weight of 0.5 whereas a term with explicitly extreme/zealous connotation was given a weight of 1. In assigning weights, context around each word–sentences around the word–was also taken into consideration.

| Terms | Terms (skewness value) | +/- Skewness |

| 1 | Khilafah (1) | + |

| 2 | Murtaddin (1) | - |

| 3 | Taghut (1) | - |

| 4 | Stooges (0.5) | - |

| 5 | Crusaders (1) | - |

| 6 | Grieve (0.5) | + |

| 7 | Mock (0.5) | - |

| 8 | Shahada (1) | + |

| 9 | Kuffar (1) | - |

| 10 | Liberalism (0.5) | - |

Table 2. Terms with Skewness Values

Additionally, a STTR was calculated to assess the lexical diversity of the content. STTR should be calculated for a fixed number of words in order to have stable results. For this purpose, the content was divided into paragraphs of 200 words each and the content was cleared of all punctuation marks. To avoid artificial conflation of words in a paragraph, some terms and names were hyphenated to form compound words so they could be counted as one word. Each paragraph was visually inspected before calculating the ratio. The STTR was then calculated for every paragraph (see Table 3 for results).

| Paragraph | STTR |

| 1 | 57% |

| 2 | 56% |

| 3 | 57% |

| 4 | 64% |

| 5 | 59% |

| 6 | 63% |

| 7 | 52% |

| 8 | 58% |

Table 3. Standardized Type Token Ratio

Three qualitative properties of ISIS’s content were also assessed including ‘accuracy’, ‘consistency’, and ‘objectivity’ as defined below in Table 4. [All definitions were quoted from Wang and Strong (1996) as cited in Knight and Burn (2005)]53

| Term | Definition |

| Accuracy | ‘extent to which data are correct, reliable and certified free of error’ |

| Consistency | ‘extent to which information is presented in the same format and compatible with previous data’ |

| Objectivity | ‘extent to which information is unbiased, unprejudiced and impartial’ |

Table 4. Definitions

The accuracy of ISIS’s content varied; for instance, in describing combat- related activities, exact locations and the number of causalities not always being clear. In terms of consistency, it can be argued that ISIS has been very persistent. For example, information was presented along with very carefully- developed visuals. The content was well-written and also supported through carefully-developed arguments. Objectivity is a property that was extremely lacking in ISIS’s content. This group, skilfully, presents either a highly-positively-skewed argument to promote their agenda or uses highly- negatively-skewed information to create feelings of hatred, anger, and fear as identified in Table 5.

| Qualitative Property | Example |

| Accurate | ‘...leading to a number of the barracks…and a large number of the murtaddin…’54 |

| Accurate | ‘…operation with an explosive vehicle, killing and wounding dozens of murtaddin…’55 |

| Objectivity | ‘…the taghut regime of…with the approval of their judges and the support of their scholastic stooges, …’56 |

| Objectivity | ‘…operations conducted by the soldiers of khilafah against the factions of apostasy in all their colors…’57 |

|

Consistency |

‘The soldiers of khilafah…apostate foot patrol…’, ‘… injuring several apostates….’, ‘…retreat of those apostates therein…’58 |

|

Consistency |

‘…leading to [a] number of barracks…and a large number of the murtaddin…’; ‘The murtaddin’s positions were bombarded…’; ‘He succeeded in killing approximately 80 murtaddin and…’59 |

Table 5. Qualitative properties

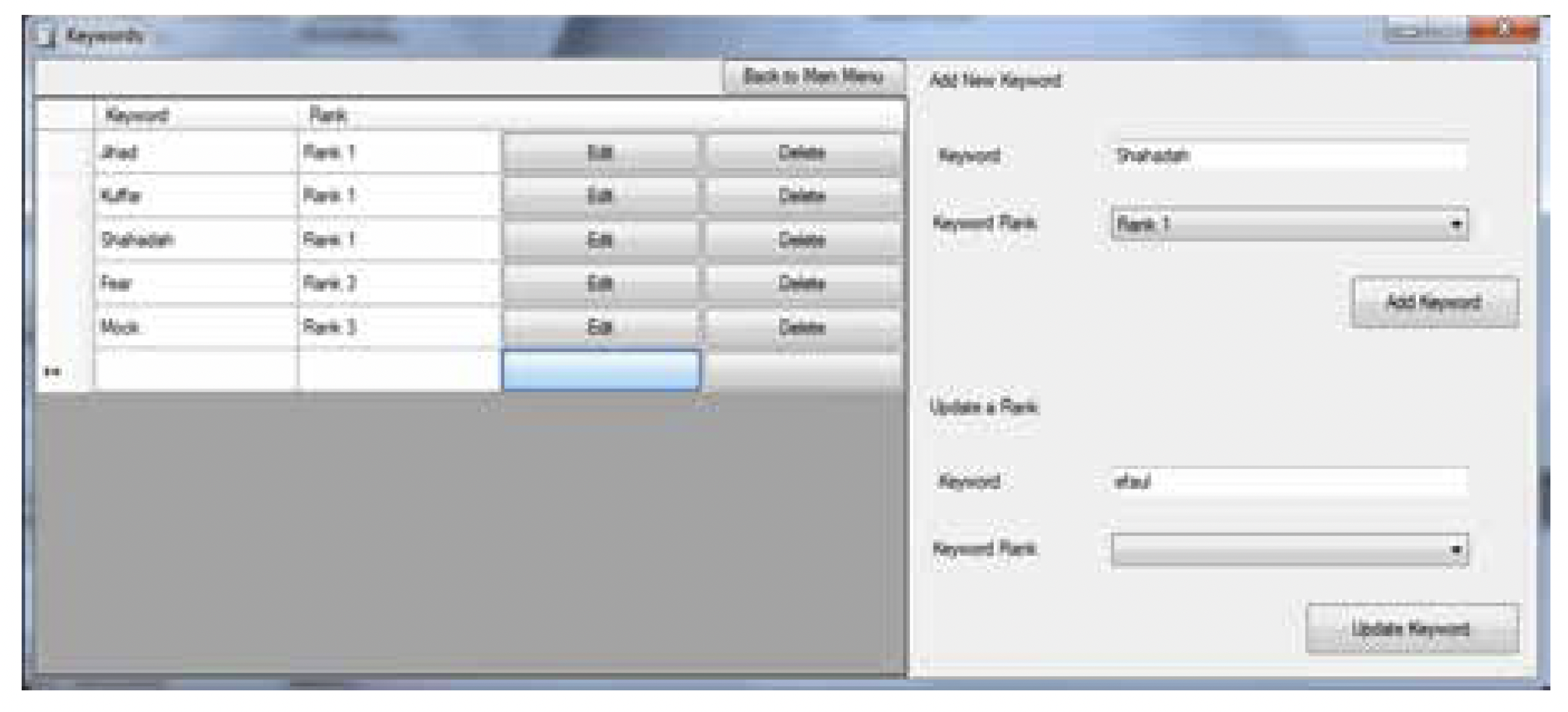

Based on the framework above including: (1) an assessment of information skewness; and (2) the classification of terms in categories using affective, emotional, political, historical and religious aspects, a pseudocode was written. The purpose of this pseudocode was to systematize the identification of extremist information and assessment of associated risk of radicalization. A prototype has been developed and tested with promising results. This prototype is an initial step in the much-needed future work to systematize the proposed framework in this study (see below some screenshots of the prototype).

Figure 1. Interface

Figure 2. Lexicon input

For comparative analysis of extremist content between ISIS and The Three Percenters we followed the data, from platform to platform, harvesting samples for the study’s dataset. For ISIS, use of the micro-blogging site Twitter was of particular prominence in building networks of supporters for the distribution of news, battle reports and propaganda. This approach was supported with the use of document-sharing sites like JustPaste.it (https:// justpaste.it/) for photo-journalism and the appropriation of the Internet Archive (https://archive.org/) to distribute video.

Use of Twitter by ISIS operatives and supporter networks has been explored in previous studies. Berger and Strathearn60, Berger and Morgan61, Shaheen62, and Fisher63 have shown how Twitter allows ISIS supporters to develop networks that are agile and adaptive, self-repairing and durable (what Fisher describes as a ‘swarm’). These qualities were evident in this study’s dataset; with multiple instances of accounts that were returning from suspension and rejoining the swarm. This swarm-like organic character to the ISIS online presence crosses platforms, as both official and unofficial operatives play cat-and-mouse with the suspension policies of social media corporations. By February of 2016, Berger and Perez64 were demonstrating that Twitter’s renewed focus on the suspension of ISIS propaganda accounts was having an effect and that the organization was shifting operations to encrypted channels. Again, this observation was clear from our dataset. By the time we had undertaken the process of analysis, all the ISIS-supporting Twitter accounts in the study’s dataset had been suspended.

The Three Percenters, in contrast, favoured Facebook, a channel providing significant reach to, and engagement with, a USA audience, where 71% of USA adults use Facebook (as opposed to 23% of adults using Twitter)65. For the group involved in the occupation of Malheur wildlife reserve, YouTube also provided a means to document the stand-off.

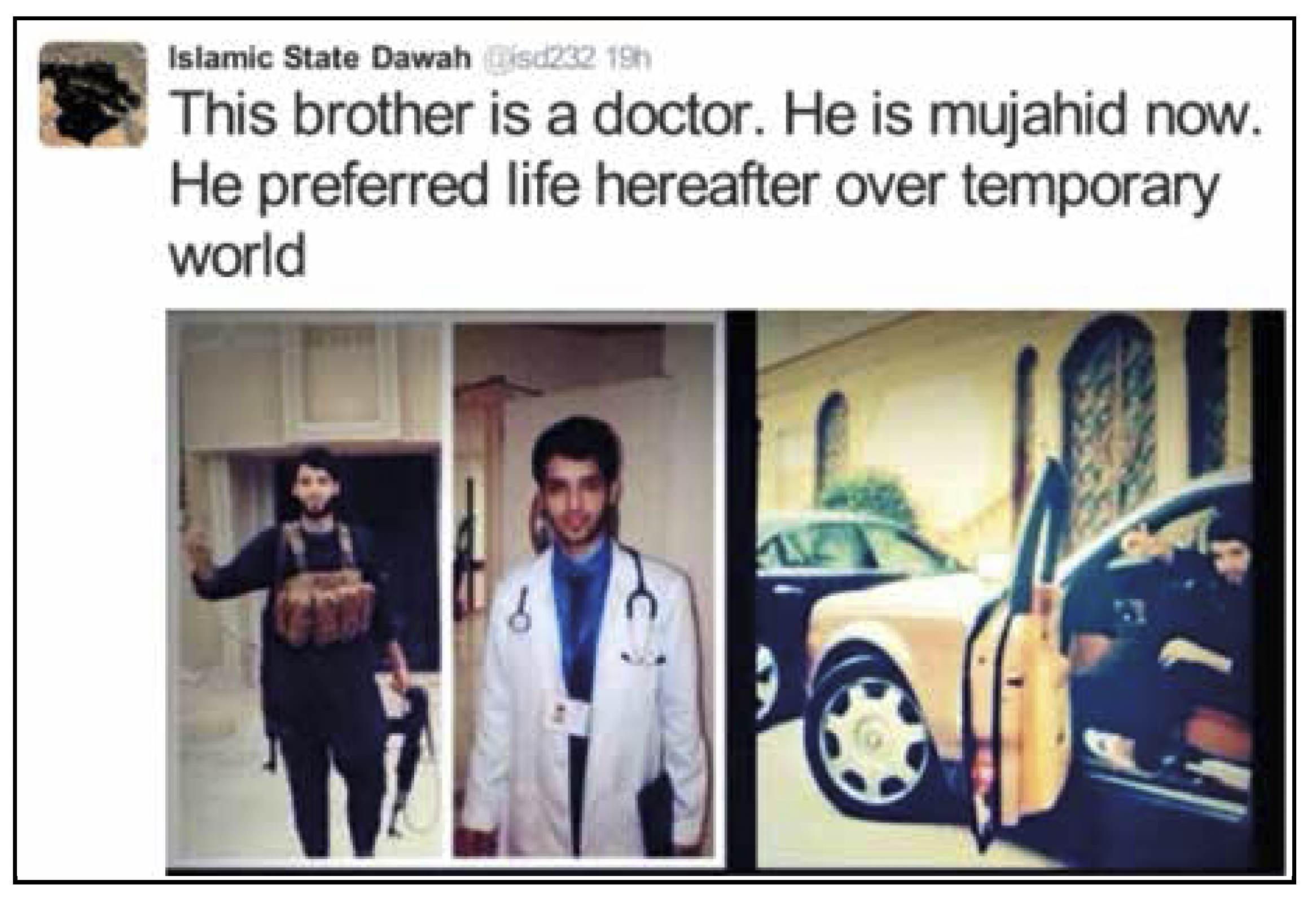

Dauber and Winkler commented on the underlying reasons for increasing use of visual imagery by extremist groups. They noted that images are processed more easily than text and hence can be more emotionally evocative and potent in drawing a response66. Our data confirmed their view, with a consistency in the symbolism that both groups employ to identify themselves as a clear brand in the extremist marketplace. There were a number of other commonalities and shared characteristics across the content from ISIS and the Three Percenters. Both groups employ consistent branding, symbolic imagery and narrative style. Both groups emphasized a sense of grievance. For ISIS, the impact of the air campaign by Coalition forces was emphasized in terms of the civilian casualties. Images of seriously-wounded or dead children were a feature of the Twitter feeds of ISIS supporter networks. Such imagery cannot fail to provoke an emotive response. When this emotional response is framed by ISIS propaganda it is clear who is to blame for this loss of innocent life. Such a powerful narrative is likely to have significant influence on the perception of a civilian population locked in the conflict zones of Iraq and Syria, as well as on diaspora communities watching from afar. For the Three Percenters, grievance was focused on a callous USA government, often referred to as ‘tyrannical’ in the dataset.

The urgency of an impending final conflict was a theme common to the narratives of both groups. According to Ingram, this communications tactic forces the audience to make a choice. It is designed to polarise, to create a context in which it becomes imperative that the audience chooses a side. In each conflict the extremist group is framing itself, for a sympathetic audience, as a protector. Appeals to a higher authority featured strongly across both groups. Both selectively quote from important texts but without appropriate contextualization and accurate interpretations67.

There were themes that emerged from the ISIS dataset that were not replicated (at least were not so emphasized) in the Three Percenters dataset. A strong theme within the ISIS dataset was the camaraderie of a military brotherhood.

Figure 3. Military camaraderie

This visual narrative presents a picture of both adventure and belonging that may be appealing to the foreign fighters who have joined the ranks of ISIS from marginalized diaspora communities. Heroic death in battle was clearly presented as the ultimate sacrifice of an ISIS fighter. Also here, significant, is that ISIS presents itself as an intergenerational project. The narrative is clear; the Caliphate is a project that has continuous momentum. It is ‘lasting and expanding’ (the group’s slogan–baqiya wa tatamaddad)68.

Figure 4. Continuous project

Endnotes

- Isdale, S. (2014) Tactical cyber #itsthe future. Australian Army Land Power Forum. Available at http://www.army.gov.au/Our-future/Blog/ Articles/2014/10/Tactical-cyber-itsthefuture

- Kilcullen, D. (2014) The Australian Army in the urban, networked littoral. Available from the Australian Army at http://www.army.gov. au/~/media/Army/Our%20future/Publications/Papers/ARP%202/ Kilcullen_11August.pdf

- Russell, G. W (2015) Operation Protective Edge: Social media observations. Australian Army Land Power Forum. Available at http:// www.army.gov.au/Our-future/Blog/Articles/2015/10/Social-media

- Australian Army (2014) Future Land Warfare Report. Available at http:// www.army.gov.au/~/media/Army/Our%20future/Publications/Key/ FLWR_Web_B5_Final.pdf

- J. P. Farwell, ‘The media strategy of ISIS’, Survival, Vol. 56, No. 6, 2014,p. 49–55.

- J. Arquilla, ‘Twenty years of cyberwar’, Journal of Military Ethics, Vol. 12, No. 1, 2013, p. 80–87.

- J. Arquilla, D. Ronfeldt and M. Zanini, ‘Networks, netwar, and information-age terrorism’, in Countering the New Terrorism, eds. Z. Khalilzad, J.P. White and A. Marshall, RAND: California, 1999, p. 75–111.

- Modernisation and Strategic Planning – Army Australian Headquarters, ‘Army’s Future Land Operating Concept’, Canberra, Australia, 2009, at http://www.army.gov.au/Our-future/Publications/Key-Publications/ Adaptive-Campaigning, accessed on 9 February, 2015.

- D. Kahneman and A. Tversky, ‘Choices, Values and Frames’, Cambridge University Press, UK, 2000.

- Oxford English Dictionary, see http://www.oed.com/, accessed on 1 February 2015.

- A. Sotlar, ‘Some Problems with a Definition and Perception of Extremism within a Society’, in Policing in Central and Eastern Europe: Dilemmas of Contemporary Criminal Justice, eds. G. Mesko, at https:// www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/Mesko/208033.pdf, 2004, p. 703–707.

- G. Saucier, L. G. Akers, S. Shen-Miller, G. Knezevic and L. Stankov, ‘Patterns of thinking in militant extremism’, Perspectives on Psychological Science, Vol. 4, No. 3, 2009, p. 256–271.

- ‘The revolution will be posted’, The New York Times, 2004, http://www. nytimes.com/2004/11/02/opinion/02blogger-final.html?_r=0, accessed on 9 February 2015.

- N. Eltantawy and J. B. Wiest, ‘Social media in Egyptian revolution: Reconsidering resource mobilization theory’, International Journal of Communication, Vol. 5, p. 1207–1224.

- Future Land Warfare Report, p. 21.

- Farwell, Media Strategy of ISIS, p. 49.

- P. R. Neumann, ‘Foreign fighter total in Syria/Iraq now exceeds 20,000; surpasses Afghanistan conflict in 1980s, ICSR Insight, 2015, http:// icsr.info/2015/01/foreign-fighter-total-syriairaq-now-exceeds-20000- surpasses-afghanistan-conflict-1980s/, accessed on 7 March 2016.

- Ibid

- E. Bakker and P. Grol, ‘Motives and considerations of potential foreign fighters from the Netherland’, International Centre for Counter-Terrorism Policy Brief, The Hague, 2015.

- J. Hall, ‘Canadian foreign fighters and ISIS’, Major Research Paper: University of Ottawa, Canada, 2015.

- D. H. Heinke, ‘German jihadists in Syria and Iraq: an update’, ICSR Insight, http://icsr.info/2016/02/icsr-insight-german-jihadists-syria-iraq- update/, accessed on 7 March, 2016.

- E. Kohlmann and L. Alkhouri, ‘Profiles of foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq’, CTC Sentinel, Vol. 7, No. 9, 2014, p. 1–5.

- M. Morell, ‘What comes next, and how do we handle it?’, Times Magazine, 2015, p. 60.

- E. Bakker and P. Grol, Motives and Considerations, pp. 13–14.

- J. Mueller and M. G. Stewart, ‘Terrorism, counterterrorism, and the Internet: The American cases’, Dynamics of Asymmetric Conflict, Vol. 8, No. 2, 2015, p. 176–190.

- L. E. Porter and M. R. Kebbell, ‘Radicalization in Australia: examining Australia’s convicted terrorists’, Psychiatry, Psychology, and Law, Vol. 18, No. 2, 2010, p. 212–231.

- Y. W. Lee, D. M. Strong, B.K. Kahn and R. Y. Wang, ‘AIMQ: A methodology for information quality assessment’, Information and Management, Vol. 40, 2002, p. 133–146.

- S. A. Knight and J. Burn, ‘Developing a framework for assessing information quality on the World Wide Web’, Information Science Journal, Vol. 8, 2005, p. 160–172.

- D. Aboody and B. Lev, ‘Information asymmetry, R&D, and Insider Gains’, Journal of Finance, Vol. 55, No. 6, 2000, p. 2747–2766.

- W. Afzal, D. Roland and M. Al-Suqri, ‘Information asymmetry and product valuation: An exploratory study’, Journal of Information Science, Vol. 35, No. 2, 2009, p. 192–203.

- K. L. Keller and R. Staelin, ‘Effects of quality and quantity of information on decision effectiveness’, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 14, 1987, p. 200–213.

- G. Keller, B. Warrack and H. Bartel, ‘Statistics for management and economics’, (2nd edn.), Wadsworth Publishing Company, CA: Belmont, 1990, p. 48.

- W. Afzal, ‘Towards the general theory of information asymmetry’, in Information Seeking Behavior and Technology Adoption: Theories and Trends, eds. M. N. Al-Suqri and A. S. Al-Aufi, PA: IGI Global, Hershey, 2015, p. 124–135.

- Lee et al., AIMQ, p. 162.

- Knight and Burn, Developing a Framework, p. 162.

- P. M. McCarthy and S. Jarvis, ‘MTLD, voc-D, and HD-D: A validation study of sophisticated approached to lexical diversity assessment’, Behavior Research Methods, Vol. 42, No. 2, 2010, p. 381–392.

- S. Sunshine, ‘Profiles on the right: Three Percenters’, 2016, at http:// www.politicalresearch.org/2016/01/05/profiles-on-the-right-three- percenters/#sthash.qjDrUbcq.dpbs

- S. Levin, ‘Heavily armed men offer ‘security’ for Oregon militia at wildlife refuge’, The Guardian, 2016, http://www.theguardian.com/us- news/2016/jan/09/oregon-militia-wildlife-refuge-heavily-armed-men, accessed on 5 August 2106.

- Dabiq Magazine, see http://www.clarionproject.org/news/islamic-state- isis-isil-propaganda-magazine-dabiq, accessed on 5 February 2016.

- Ibid.

- Ibid

- J. A. Russell, ‘Core affect and the psychological construction of emotion’, Psychological Review, Vol. 110, No. 1, 2003, p. 145–172.

- A. Ortony, G.L. Clore and M.A. Foss, ‘The psychological foundations of affective lexicon’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 53, 1987, p. 751–766.

- Heinke, German Jihadists.

- D. Weggemans, E. Bakker and P. Grol, ‘Who are they and why do they go: The radicalisation and preparatory processes of Dutch jihadist foreign fighters’, Perspectives on Terrorism, Vol. 8, No. 4, 2014, p. 100–110.

- Hall, Canadian Foreign Fighters, p. 17.

- Ingram, Three Traits, p. 4.

- H. K. Gambhir, ‘DABIQ: The strategic messaging of the Islamic State’, Institute for the Study of War, 2014, at https://www.understandingwar. org/backgrounder/dabiq-strategic-messaging-islamic-state, accessed on 5 February 2016.

- M. Steindal, ‘ISIS totalitarian ideology and discourse: an analysis of the Dabiq Magazine discourse’, PhD Thesis, Norwegian University of Life Sciences, 2015.

- Dabiq Magazine, see http://www.clarionproject.org/news/islamic-state- isis-isil-propaganda-magazine-dabiq, accessed on 5 February 2016.

- Islamic State News Bulletin, https://halummu.wordpress.com/category/ news/, accessed on 10 March 2016.

- Ortony et al, ‘The psychological foundations of affective lexicon’

- Knight and Burn, Developing a Framework, p. 162.

- Dabiq Magazine, p. 19

- Ibid, p. 18

- Ibid, p. 7

- Ibid, p. 14

- Islamic State News Bulletin

- Dabiq Magazine, p. 19.

- J. M. Berger and B. Strathearn, ‘Who matters online: Measuring influence, evaluating content and countering violent extremism in online social networks; Developments in Radicalisation and Political Violence’, The International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence, 2013, at http://icsr.info/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/ICSR_ Berger-and-Strathearn.pdf

- J. M. Berger and J. Morgan, ‘The ISIS Twitter Census: Defining and describing the population of ISIS supporters on Twitter’, The Brookings Project on U.S. Relations with the Islamic World, Analysis Paper No. 20, The Brookings Institution, 2015, at http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/ research/files/papers/2015/03/isis-twitter-census-berger-morgan/isis_ twitter_census_berger_morgan.pdf

- J. Shaheen, ‘Network of Terror: How Daesh uses adaptive social networks to spread its message’, NATO, 2015, at http://www. stratcomcoe.org/network-terror-how-daesh-uses-adaptive-social- networks-spread-its-message

- A. Fisher, ‘Swarmcast: How Jihadist networks maintain a persistent online presence’, Perspectives on Terrorism, Vol. 9, No. 3, 2015, p. 3–20.

- J. M. Berger and H. Perez, ‘The Islamic State’s Diminishing Returns on Twitter: How suspensions are limiting the social networks of English- speaking ISIS supports’, The Program on Extremism at George Washington University, 2016, at https://cchs.gwu.edu/sites/cchs.gwu. edu/files/downloads/Berger_Occasional%20Paper.pdf

- Pew Research Center, ‘Social networking factsheet’, 2014, at http:// www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheets/social-networking-fact-sheet/

- C. E. Dauber and C. K. Winkler, ‘Radical visual propaganda in the online environment: an introduction’, in Visual propaganda and extremism in the online environment, eds. C. E. Dauber and C. K. Winkler, U.S. Army War College, Strategic Studies Institute, Carlisle: PA, 2014, p. 1–31.

- H. Ingram, ‘Three traits of the Islamic State’s information warfare’, The RUSI Journal, Vol. 159, No. 6, 2014, p. 4–11.

- L. Khatib, ‘The Islamic State’s strategy: lasting and expanding’, Carnegie Middle East Center, 2015, at http://carnegieendowment.org/ files/islamic_state_strategy.pdf