Abstract

The twenty-first century is increasingly challenging the efficacy of Cold War era non-proliferation regimes intended to prevent the spread of weapons of mass destruction (WMD). There are significant limitations to the contemporary reliance on these regimes and associated interdiction activities intended to prevent proliferation. The existing controls have failed to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons to states that previously did not possess such weapons, and there are also continuing concerns that catastrophic weapons, including weapons of mass effect (exemplified by the September 11 attacks), will be acquired or developed by non-state actors to fundamentally threaten the traditional state monopoly on legitimate violence. This article examines the existing system of global proliferation controls, the relevance of the growing risk gap, and policy and capability decisions that may reduce this gap. To mitigate this threat, Australia must start with an integrated concept that integrates existing non-proliferation efforts with maritime strategy, and considers broad social and technological changes.

Introduction

Hopes that the end of the Cold War would usher in a period of relative stability and general economic prosperity have largely evaporated. The superpower paradigm of United States (US)–Soviet relations was superseded by a period of US hegemony and has now evolved into a multi-polar economic and security environment. This environment has heralded the emergence of proxy forces and the strategic rise of violent non-state and sub-state actors. Terrorism, once considered a weapon of the weak,1 has metastasised into the strategically ambitious ‘new terrorism’ capable of challenging Westphalian concepts of state and power. Foreign Minister Julie Bishop has described contemporary terrorism as ‘more dangerous, more complex, more global than we have witnessed before – a pernicious threat that could, if left unchecked, wield great global power that would threaten the very existence of nation states.’2

Traditionally, nuclear deterrence diminished the risk of warfare between nuclear-armed states while a web of proliferation controls attempted to restrict weapons of mass destruction (WMD) technology to the few advanced nations that possessed them. However, in an era of globalisation and technological diffusion, this technological monopoly no longer exists and the incidental diffusion of technology and information continues to erode controls aimed at containing the spread. Efforts at containment are further challenged by contemporary terrorism and violent non-state actors (VNSA) for which the traditional controls were not designed and are largely inappropriate.

Beyond widely discussed concerns over non-state actors’ acquisition or development of WMD, there are also fears that unconstrained terrorist organisations will employ new techniques or widely available technology to conduct catastrophic acts of terrorism such as those of September 11. These attacks, using what have been termed ‘weapons of mass effect’, pose a potential threat to Australian national interests and require a revision of the policies, capabilities and relationships designed to mitigate this threat. A national approach to counter catastrophic threats from VNSA may represent a significant divergence from the traditional approach employed to counter WMD.

This article examines the potential for terrorist acquisition or use of catastrophic weapons and the possible role of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) in developing a means to mitigate this threat. This discussion will cover a number of areas, providing an overview of current policies, addressing the growing risk gap, and examining policy and capability decisions that may reduce the risk of catastrophic terrorism. For the sake of brevity, this article will focus on technological advances and social changes relating to the chemical and biological threat areas rather than the more general trends affecting high-impact (catastrophic or mass effect) terrorism.3 The article will also highlight issues of concern, principally in areas with Defence policy and capability implications versus broader preventative strategies such as social inclusion, incarceration processes and customs screening. Specific weapon threats and countermeasures (such as prophylaxis to specific biological threats) will not be addressed in this discussion.

Current state of relevant policy

Given the heightened post-9/11 concern over the potential for terrorist acquisition of WMD, there is remarkably little consensus among developed nations on key definitions of terrorism and WMD. A fundamental issue is the disparate political and military interpretations of which weapons comprise WMD. The definitive 1948 United Nations (UN) definition is:

... atomic explosive weapons, radioactive material weapons, lethal chemical and biological weapons, and any weapons developed in the future which have characteristics comparable in destructive effect to those of the atomic bomb or other weapons mentioned above.4

While the UN definition includes ‘any weapons developed in the future’ with comparable destructive effects, previous attempts at expanding UN controls (such as those attempted for radiological weapons, infrasound weapons, and genetic weapons affecting the mechanism of hereditary) have demonstrated the UN’s inability to pre-emptively progress resolutions that cover ‘exotic’ and ‘non-existent’ weapons.5 The term WMD continues to be employed liberally to include a broad range of threats. For instance, in 2001, then director of the US Defense Threat Reduction Agency, Major General Bongiovi, presented testimony that included an expansive WMD definition:

… the definition encompasses nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons. However, it also includes radiological, electromagnetic pulse, and other advanced or unusual weapons capable of inflicting mass casualties or widespread destruction. In addition, conventional high explosive devices, such as those used in the attacks on Khobar Towers and the USS COLE, are legally and operationally considered to be WMD.6

The Australian definition of WMD is included in the Weapons of Mass Destruction (Prevention of Proliferation) Act 1995. The Act states that a ‘WMD program means a plan or program for the development, production, acquisition or stockpiling of nuclear, biological or chemical weapons or missiles capable of delivering such weapons.’7 Both the UN definition and the Australian definition include all chemical and biological weapons and do not discriminate as to the potential lethality of the WMD itself or the actual lethality of any attack. This implies that a chemical poisoning attack with limited fatalities or casualties may be considered a WMD attack (such as the 1995 Tokyo subway attack) whereas an incident such as the Bali bombing that killed 202 people would not qualify under the terms of the definition.

Within this context, scholars and policy-makers have recognised that it is not just the destructiveness of the weapon that matters but its net impact, including financial, psychological and catastrophic disruption — giving rise to the term weapons of ‘mass effect’ (WME). The most prominent policy document that refers to WME is the 2004 US National Military Strategy that contained this definition of WMD/E:

WMD/E relates to a broad range of adversary capabilities that pose potentially devastating impacts. WMD/E includes chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and enhanced high explosive weapons as well as other, more asymmetrical ‘weapons’. They may rely more on disruptive impact than destructive kinetic effects.8

The term WMD/E was removed from the subsequent 2005 US National Defense Strategy and replaced with broad descriptors of the threat posed by ‘an array of traditional, irregular, catastrophic, and disruptive capabilities’.9 While the term WME has not gained traction in the media and has limited reference in political discourse, it has continued to pervade academic literature, particularly within the US. The definition of WME is considerably broader than WMD and encompasses innovative and spectacular attacks where one of the following is true:

… the number of people killed is over 100; the attack devastated a large area – a square mile of a city or ten square miles in rural areas; the attack damaged or destroyed a critical facility, such as a power plant, a major airport, or an important government office; the attack disrupted everyday services enough to cause a significant reduction in quality of life; the attack caused significant loses to the target (eg, $10 billion for the United States, less for developing nations); the attack provokes and manifests a degree of terrorism – a subjective but nonetheless present psychological or emotional impact on the population.10

WME in the Australian context are listed as a potential threat in the Australian Army’s Future Land Warfare Report. However the document makes no attempt to define these weapons beyond stating that they involve ‘dual use technologies’.11 While there are few policy or academic documents that specifically list the methods of attack for WME, the available references usually refer to nuclear, biological, chemical, radiological and conventional weapons.12 Other mechanisms of attack include kinetic energy (planes, trains etc.), incendiaries (large urban fires), toxic gases, biological and chemical agents, agricultural sector attacks, industrial explosions, flooding, and disrupting or breaking critical infrastructure including cyber attacks.13

This broader WME definition encompasses more of the likely scenarios for attacks by terrorist organisations or non-state actors, and those that are more likely to have political or significant security consequences. Importantly, WME include sociological effects rather than simply material destruction. Differentiating by effect creates a situation in which some WME attacks will involve WMD, and some WMD attacks will be classed as the result of WME — but not all. The broader definition also fosters conceptual discussions without conflating some methods of attack as involving WMD (i.e. cyber attacks). Differentiating WME, and the public perception of their manifestation as terror weapons, may more accurately represent the community expectation of the government’s responsibility to provide security.

Existing controls

UN non-proliferation controls were largely developed within a context of state-on-state conflict in the post-World War II and Cold War eras. These primarily involved the available technology and expected military utility of the time. While these controls have been partially successful in limiting the proliferation of nuclear weapons beyond the prescribed nuclear weapons states, they have not been wholly successful in curtailing ‘illicit’ nuclear programs (for instance, those of Israel, Pakistan and North Korea). The state proliferation and use of chemical and biological weapons are controlled by what is commonly termed the Chemical Warfare Convention 1997 (CWC) and the Biological Warfare Convention 1975 (BWC).

The CWC departs from the previous practice of limiting the deployment and number of certain types of munitions and instead ‘aims to eliminate an entire category of weapons of mass destruction’.14 Since the almost universal adherence to the CWC, state use of chemical weapons has been limited. A recent exception has been Syria’s repeated use of chemical weapons in 2013, including the 21 August 2013 attack in Ghouta that resulted in the deaths of some 1400 people.15 Despite the subsequent destruction of Syria’s declared chemical weapons stockpile, chlorine gas has been found to have been ‘systematically and repeatedly used’ as a weapon in Syria throughout 2014.16

The BWC shares a common goal with the CWC in that it seeks to prohibit, and not just limit, an entire class of weapon. However, a number of limitations exist that challenge the efficacy of the BWC. For example, much of the science and technology required for a bio-weapons program can have beneficial therapeutical and industrial applications. In an exemplary case, researchers at the Australian National University conducting genetic splicing made previous genetically immune mice populations susceptible to a virus and nullified the effects of vaccination.17 This published research raised concerns that terrorists could produce a strain of vaccine-resistant smallpox via the ‘explicit instructions’ provided to them by the study.18 Reaction to this experiment typifies concerns over the dual-use nature of biological research and the ability of technological diffusion to lower barriers to illicit use.

In the post-9/11 security environment, the efficacy of Cold War era proliferation controls in preventing non-state acquisition and use of WMD has been questioned, resulting in the implementation of a number of additional control mechanisms.19 These include the Proliferation Security Initiative, United Nations Security Council Resolution 1540 and the Australia Group initiative.

The Proliferation Security Initiative

In 2002, a North Korean-flagged vessel bound for the Middle East was boarded by Spanish special forces who discovered 15 Scud B missiles hidden in the hold. Yemen subsequently claimed ownership of the missiles, citing intended defensive use, and the missiles were then released.20 In response, the US launched the Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI), a voluntary coalition of states determined to ‘use their national resources, including force if necessary, to interdict and seize international shipments of goods believed to be destined for use in WMD programmes.’21

The initiative itself relies on voluntary adherence, on a case-by-case basis, to a set of interdiction principles and, as the PSI Chairman reiterated at the fifth PSI conference, ‘PSI is an activity, not an organization.’22 While the participants have been described as acting in a manner similar to a ‘deputised posse’, albeit consistent with existing national and international laws,23 others have been critical of the lack of legal basis for the PSI, in particular the innocent right of passage where it is argued that ‘the threat presented by WMD material is determined by the intended use at the point of destination, not transit.’24 In the case of the threat posed by proliferation of dual-use chemical and biological pre-cursors, the end use of the material can be far more readily argued as destined for peaceful industrial purposes. Consequently, the threshold for legal pre-emptive interdiction action would be significantly higher than in the case of the Scud missiles.

UNSCR 1540

The shortcomings of the PSI were in part ameliorated by UN Security Council Resolution 1540 (UNSCR 1540) in 2004 which urged states to ‘establish … and maintain effective national export and trans-shipment controls’ over systems and products that would contribute to proliferation.25

UNSCR 1540 was specifically written to reinforce the existing regimes, while expanding the remit to include non-state actors. Unlike existing conventions, UNSCR 1540 imposed ‘binding non-proliferation obligations outside the traditional process of negotiations’.26 However many countries lack the domestic capacity (or perceived prerogative) to establish a suitable legal and enforcement framework. While UNSCR 1540 has universal applicability, it can be perceived as an indirect means to add legitimacy to the PSI, and consequently discourages countries opposed to the PSI from adhering to the convention. The national imperative or commercial interests can often outweigh the benefits of compliance.

The Australia Group

Both the CWC and BWC assist in constraining the movement of goods and technology intended for hostile purposes. However, there is a lack of inherent pre-emptive urgency within the treaty negotiation process and a ‘mismatch between the rapid pace of technological change and the relative sluggishness of multinational negotiation and verification’.27 This inertia has provided an impetus for the establishment of an increasing array of industry/government cooperative initiatives. The Australia Group (AG) is one example of these cooperative initiatives. The AG is a voluntary organisation that aims to use ‘licensing measures to ensure that exports of certain chemicals, biological agents, and dual-use chemical and biological manufacturing facilities and equipment, do not contribute to the spread of Chemical and Biological Weapons.’28 However, the AG initiative suffers from a lack of universal acceptance, including among large industrial nations such as China, Russia and India. China was particularly vocal in its criticism, asserting that the AG represented a split legal system and should be dissolved.29 Lack of conformity in behavioural norms, particularly where commercial interests are concerned, remains a major obstacle and items prohibited by the AG remain readily available for purchase from sources such as Alibaba using common payment methods.30

The relevance of the growing risk gap

A number of developments have increased the risk posed by the gap between reliance on the traditional ‘non-proliferation’ controls and the pervasive social and technical trends that characterise the contemporary operating environment. These include the effects of globalisation and the emergence of ‘new terrorism’.

Globalisation

Globalisation, enabled by improved telecommunications technology, increasingly pervasive and ubiquitous social and news media, and cheaper movement of goods and people, has resulted in a socio-economic environment connected beyond the traditional barriers imposed by state and country borders. This has occurred alongside predicted growth in mega- cities, a change in the wealth and consumption habits of Asian economies, and an eastward movement in the economic centre of gravity away from Western Europe and into Central Asia.31 These changes in consumption have driven a change in production patterns as organisations seek to move production closer to their consumer base. This has resulted in geographical shifts in research and production bases within the chemical32 and biotechnology industries.33 These changes have led to increased diffusion of the materials, hardware and knowledge that comprise ‘dual use’ elements, potentially reducing the traditional constraints to obtaining WMD.34 The PSI’s traditional focus on containment of potentially highly destructive technology to a few advanced states is no longer the dominant paradigm. Technological diffusion is likely to continue and mix with violence in unexpected ways.

New terrorism

It is generally accepted that the contemporary terrorist threat is evolving and has prompted some analysts to brand twenty-first century terrorism as fundamentally different from the terrorism of the 1970s and 1980s. Some have argued that this ‘new terrorism’ is increasingly strategic in nature:

… new terrorism is more strategically focused. Its objective is to roll back Western values, engagement and influence, and to weaken and ultimately supplant moderate Islamic governments ... Al Qaida and its associated networks have demonstrated both willingness and capability to inflict massive casualties on civilian targets as a strategic end.35

This ‘new terrorism’ has significant implications for traditional strategies designed to prevent WMD/E attacks including those associated with the diffusion of power, terrorist organisational diffusion, and reduced constraints.

Diffusion of power. Traditionally, the state alone has held the monopoly on legitimate violence. As Weber asserts, the state is the ‘human community that [successfully] claims the monopoly on the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory.’36 However, the dynamics of non-state power are changing. Particularly pernicious campaigns of terrorism, associated with new terrorism, threaten this monopoly. Where twentieth-century terrorist organisations were predominantly reliant on state sponsorship, and in many cases acted as proxy forces for state actions, the terrorism support base is increasingly fracturing into an amorphous constituency (the crowd sourcing of terrorism). The new paradigm is one in which groups can be equally successful in operating within a failed or weak state, in ungoverned spaces within existing nation states or online, or as a terrorist state. This challenges both the traditional concept of states and also the relative power of states. Terrorism thus demonstrates that it is not just the size of militaries that matters, but also the strategy employed to convert resources to outcomes. WMD and catastrophic acts of terrorism pose an ‘ultimate asymmetric threat’ to further challenge traditional power constructs.37

While ‘new terrorism’ has the potential to usurp the power associated with states, the seemingly unstoppable growth of terrorist groups is also supported by other disruptive technologies that are spreading power from centralised to diffuse organisations. For example, Wikileaks challenges the government containment of sensitive information; technology such as 3-D printing and additive manufacturing has allowed the development of garage manufacturing; and peer-to-peer lending services and digital currency are challenging the monopoly of traditional central banking systems. These technologies empower individuals and small groups, while concurrently challenging existing institutions and traditional controlling regimes.38

Terrorist organisational diffusion. Where once Al-Qaeda was a hierarchical organisation with a clear chain of command (similar to Marxist doctrine) and a relatively limited geographical span, it has now developed (or devolved) into a group of aligned organisations working to a common strategic purpose. Contemporary Al-Qaeda has largely assumed a flat, leaderless structure and, in doing so, has decreased the utility of counter-leadership operations.39 Counter-terrorism and counter-WMD/E strategies must evolve to address organisations that are increasingly resistant to external interference.

A number of contemporary factors have increased the prominence of decentralised groups and leaderless resistance structures. The first is the almost universal adoption of technology to enable terrorist groups to communicate (internally and externally), even within traditional conflict zones, and effectively conceal their signature within the signals clutter of modern life.40 Second, counter-terrorism and counter-leadership operations have reduced the effectiveness and survivability of traditional hierarchical organisations. Where terrorist control had traditionally been exerted via a leader/subordinate relationship, perceptions of the ubiquitous nature of contemporary terrorism are, in part, derived from online sources exhorting followers to conduct terrorist actions whenever and wherever they can, removing the requirement for additional coordination and reducing the risk of detection.

New terrorism and reduced constraints. While traditionally terrorist group activities were moderated by reliance on the direct support of state sponsorship, by contrast ‘new terrorism’ is likely to be supported by indirect funding from a variety of sources. This reduction in direct state sponsorship reduces constraints on action as, ‘presumably, groups with amorphous constituencies are less likely to worry about the opprobrium that would accompany their use of WMD.’41 The new era of terrorism is one in which violence has evolved from a means to leverage negotiating power to an end state in itself. Whereas previously, appealing to constituencies or constraints imposed by state sponsorship acted to moderate unconstrained violence, ‘Today’s Terrorists don’t want a seat at the table, they want to destroy the table and everyone sitting at it.’42 This trend is enabled by capabilities such as the ‘dark’ internet, negotiable goods, encryption technology, and new finance technology (such as Bitcoin). These technologies all increase the possibilities for illicit transfer of knowledge and resources.

Possible Australian policy and capability responses

Against the real and immediate problems facing the ADF, the possibility of terrorists employing WMD/E seems a low-probability event for which the ADF need only ‘be prepared’ to act where the problem is beyond civilian agency capability.43 Counter-WMD/E does not feature prominently in defence guidance and the approach to date has been managed by a small number of highly specialised personnel. However, even while the probability of such an event is low, its potential impact on the military, government and society as a whole could be catastrophic and is an ‘inevitable surprise’ that should be considered within Australia’s security strategy.44 This would provide a framework for coordinated efforts to determine the likelihood of attack, reduce the success of such an attack, and then mitigate the consequences. A unified concept could combine areas such as risk assessment methodology, the role of expanded decisive influence (including deterrence), and development of concepts to inhibit violent innovation among opposing networks.

Risk assessment methodology

A WMD/E prevention campaign must be based on an appropriate risk management framework informed by an appropriate collection plan. However, a unified vision of the strategic implications of WME in the Australian context does not exist and the current broad interpretation of the threats presented by existing WMD appears likely to continue.

The extent to which the existing Australian WMD risk assessment framework is applicable and transferable to WME is unclear. However, the two topics have significant commonality. Analysis of the threat posed by WMD terrorism requires research into the motivation to commit such acts and is important for two primary reasons. First, it concerns the overall level and imminence of the threat, and second, it provides a basis for pre-emptive action to meet these threats (through a combination of pre-emption, containment, influence or deterrence). While tempting to view terrorism as ubiquitous, in reality, acts of catastrophic terrorism are more likely among certain terrorist archetypes. Where there has traditionally been a disconnect between social scientists assessing proclivity towards employment of WMD, and ‘hard’ scientists addressing what is possible, a unified approach should effectively combine both.

Effective intelligence within a formalised risk assessment framework is critical for enabling the full spectrum of WMD/E prevention efforts. The concepts and military options available for a non-proliferation or counter-proliferation campaign depend on the evidence (intelligence) available to build consensus. As seen in Iraq, the constraints arise not when terrorists possess WMD, but when they possibly possess WMD. Despite a move towards policies of pre-emption, the scope of acceptable military activities will continue to be governed by the quantity and quality of available intelligence. Activities such as interdiction require high levels of precise intelligence to be successful. However, establishing security cooperation and building regional capacity and trust relationships do not require specific intelligence and may set the conditions for future success. Activities such as desktop exercises, data sharing and the provision of embedded officers create a unified vision of the problem, contribute to assurance, and assist in setting conditions for an effective response.

(Re-)establishing non-state deterrence

In the wake of September 11, many governments were quick to reach the conclusion that ‘deterrence is dead’, supported by a belief that, ‘unlike states, terrorist groups like Al-Qaeda cannot be constrained in their actions by negotiation or threat of retaliation.’45 However, more recently, academics and policy-makers have concluded that there is both theoretical and practical evidence of the contribution of deterrence to reducing the risk of terrorism in general46 and WMD terrorism specifically.47 An effective WMD/E prevention concept must include elements of deterrence against non-state actors. Despite the importance of this issue and a reassessment of the value of deterrence, the Australian deterrence concept for non-state actors remains underdeveloped.

A number of ADF documents highlight the importance of the ADF’s role in deterrence but there is a clear lack of a contemporary unifying strategy that illustrates the linkages between maritime strategy, deterrence (influence) concepts, counter-terrorism and counter-WMD efforts (or ideally a WMD/E prevention concept). Further, deterrence concepts must extend beyond punitive kinetic actions which risk an escalation paradigm, potentially assisting the terrorist by reinforcing the counter narrative and creating a framework for ideological opposition:

In highly complex structural situations, characterized by asymmetric (split) cultures, a lack of common knowledge, an asymmetric differentiation of actors and distribution of power and knowledge, there is a high propensity for deterrence practice to become self-defeating.48

In the army context, this ‘asymmetric differentiation’ risks being reinforced by the methods employed to engage regionally and internationally, with strong emphasis placed on technology exchange and reinforcing military relationships with Western allies. Inevitably, high relative military technology and a lack of understanding of non-Western terrorist groups will lead to a greater propensity to employ coercive deterrence. Implementation of concepts such as sea-basing and ship to objective manoeuvre49 risk increasing this power differential, a situation exacerbated by the widely held belief that non-state deterrence has failed and the alternative is pre-emption.

The ability of general purpose forces to deter non-state actors is limited by contemporary military experience that has added the concept of ‘quagmire’ to the military lexicon. The US deterrence concept describes this term as the ‘asymmetry of stakes vs. the asymmetry of power’, reinforcing the notion of self-deterrence, in which national interests are insufficient to justify the costs of intervention.50 The willingness of Australia to protect the strategic interests of a ‘stable, rules-based order’ will be challenged by WMD/E and the hyper- enabled non-state actor.51 A comprehensive WMD/E prevention concept needs to consider an expanded role for Defence influence within the context of broader strategy. This concept will reduce the perceived costs of taking action and mitigate the negative consequences of interceding. Influence is a critical capability in multilateral ‘new’ non-proliferation efforts.

Developing the spectrum of influence activities

The various constructs of contemporary terrorism complicate deterrence efforts. Depending on the context, terrorists can range from lone actors inspired by global events to terrorist armies implementing security and governance mechanisms normally associated with statehood. Even Al- Qaeda itself, often held as the organisational exemplar of new terrorism, has ‘morphed from a discrete terrorist group into a wide ranging fighting movement that conducts insurgencies, recruits foreign fighters into conflicts, raises funds, and conducts terrorism on the side – almost certainly its least resourced component.’52

This broad movement is reflected in Al-Qaeda’s self-reported doctrine which states that jihadist guerrilla warfare consists of three stages: exhaustion (limited terrorism), the balancing stage (limited decisive battles and guerrilla warfare), and finally decisiveness and liberation (area control).53 These stages can be viewed as concurrent efforts with varying degrees of ‘mass’ at different locations throughout an organisation’s presence (both physical and non-physical). The mass and presence of an organisation varies from pseudo or proto state, to guerrilla warfare or insurgency actions, and finally to bona fide terrorist groups.54 A systemic approach to defeating terrorism must address the larger system of violent opposition.

Traditionally terrorism per se has been considered incapable of achieving organisational goals.55 However, some commentators dispute this claim, arguing that terrorism has been more successful than is generally conceded, particularly when combined with other forms of violent activities such as guerrilla warfare.56 Terrorism’s motivation is less concerned with the distinctions between guerrilla warfare, terrorism and insurgency, or between the achievement of strategic and tactical objectives, than with the perception that armed resistance can be successful. As terrorism academic Martha Crenshaw asserts, ‘it is the image of success that recommends terrorism to groups who identify with the innovator.’57 So while, academically, there remains a tendency to categorise the types of opposition (insurgency or terrorism) and responses (security assistance or counter-terrorism), in practical terms these comprise a single interrelated system.

This interdependent opposition system is a highly complex network that extends into the non-physical space and includes a multitude of other actors including nation states, criminal organisations, logistics organisations and others. These nation states and criminal organisations may have informal or formal ties to the ‘terrorist’ organisation (state-sponsored terrorism or proxy warfare or the intersection of international drug trafficking organisations and groups such as the FARC and the Taliban). The interactions (or flows) between nodes can be physical (weapons, personnel) or non-physical (ideology, motivation, finances, tacit information). Disrupting these flows and nodes must be part of a systemic approach to degrading the effectiveness of terrorism and consequently the appeal of terrorism as a method. So, while critics of deterrence theory state that it is unclear how and where to target threats, a systemic view that includes other nation states and pseudo states provides both a means of communication and physical assets that can be targeted (physically or non-physically). While new terrorism may change the power dynamic between states and non-states, where interdependence exists it should be exploited for the purposes of deterrence. In addition, terrorists ‘scarcely ever, if indeed ever, exist and operate in isolation from organizations, and these organizations rarely in isolation from states; and deterrence can be brought to bear by that route.’58

Where state sponsors of terrorism are susceptible to punitive deterrence measures and general diplomacy, addressing passive state sponsorship of terrorism is far less straightforward. Passive state sponsorship is significantly more common than active sponsorship and involves failed or fragile states, or states unable to govern their own borders. As Byman argues, ‘the greatest contribution a state can make to a terrorist cause is by not acting. A border not policed, a blind eye turned to fundraising, or even toleration of recruitment, all help terrorists build their organizations and survive.’59 Further, while there is a lower utility for military forces in Western democracies (pre-crisis), there is broad utility for military actions degrading terrorist systems and positively influencing other nation states (including assurance, deterrence, co-option and capacity building).

Efforts pre-crisis serve to reassure nation states, increase indigenous capacity, reduce the effects of attacks, and set the preconditions for larger military contributions should the security situation deteriorate. In addition, as a nation moves closer to crisis, the relative role of the military increases and the domestic security apparatus, such as the police force, becomes increasingly militaristic. Relationships established pre-crisis will be critical to enable effective actions to deny the ongoing benefits of terrorism.

In addition to developing models for collective influence, efforts to increase influence will require the development of additional skills beyond the scope of traditional counter-terrorism capabilities. Military assistance contributes to strategy through ‘its ability to do something for national defense where other, more direct means would accomplish virtually nothing.’60 So where there is a risk that deterrence policy will become self-defeating, appropriate indirect capabilities, supported by doctrine and policy, may protect national interests in a way that direct military activities cannot.

Inhibiting innovation within violent non-state actor networks

A number of existing programs seek to inhibit the spread of knowledge necessary for the production of chemical or biological weapons (such as the PSI or G-8 Global Partnership) and prevent the spread of innovative technology (UNSCR 1540 and the AG). However, there appears to be less focus on actions addressing the organisational characteristics of the groups seeking to incorporate that knowledge — the demand side of proliferation. Disrupting innovation in these organisations may reinforce contemporary non-proliferation efforts.

The difficulty of producing a truly catastrophic chemical or biological weapon is perhaps demonstrated by the lack of successful employment of such weapons even among those with the motivation and financial resources to do so. While it is tempting to view technological diffusion to terrorist groups as inevitable, the ability and motivation for an organisation to introduce new methods or tools is dependent on a variety of organisational and social factors. These factors can be increasingly prohibitive to innovation among networks that are attempting to remain undetected by security and intelligence forces. These dichotomous factors (such as openness to new ideas despite concerns over security) provide an avenue for a persistent and non-traditional approach to WMD/E prevention.

While truly innovative terrorist capabilities are rare, part of the challenge of WMD/E prevention is the ability to detect when a group or individual intends to pursue a course of action that could produce catastrophic consequences.61 Eleven salient factors have been described as affecting terrorist innovation: ‘the role of ideology and strategy, dynamics of the struggle, countermeasures, targeting logic, attachment to the weaponry/innovation, group dynamics, relationship with other organizations, resources, openness to new ideas, durability, nature of the technology.’62

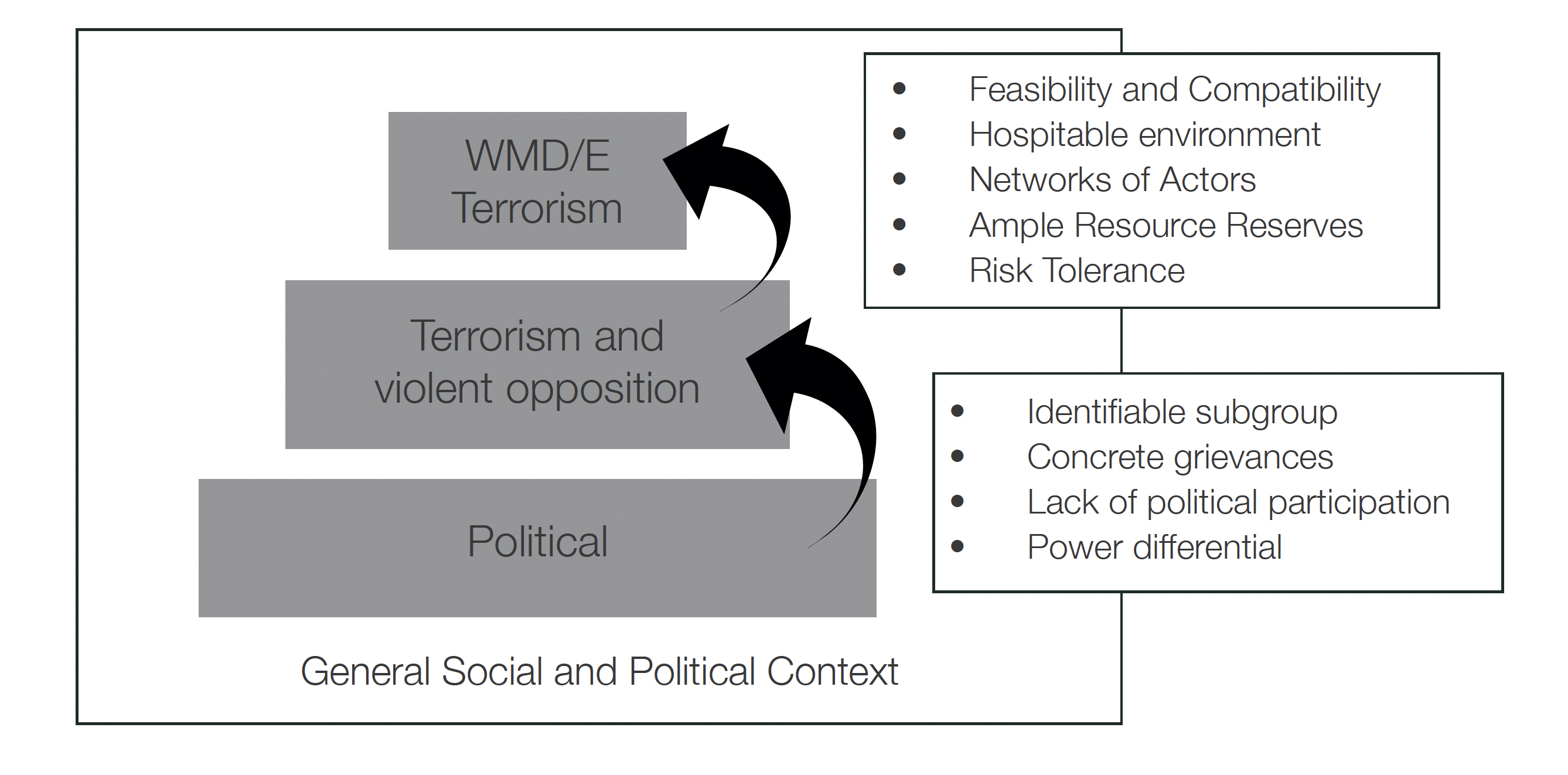

Organisational proclivity towards innovative terrorism can be combined with the broader predictors of terrorism. While terrorism may appear random from a victim perspective, terrorist events are a manifestation of a broader situation and strategy. Further, its causes can be attributed to ‘concrete grievances amongst an identifiable subgroup ... lack of opportunity for political participation’ and dissatisfaction with incumbent elites.63 Given that terrorism events are part of a broader strategy, catastrophic terrorism is also contained within a larger set of terrorist activities that have a specific set of circumstances. The requirements for this escalation paradigm are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Escalation from political dissent to WMD/E terrorism64

Among terrorist groups, indicators of proclivity to WMD/E terrorism are signalled by a number of correlating factors including group size, history of violent attacks, previous statements demonising target audiences, and history of chemical weapon production or use.65 The preconditions for WME innovation provide a basis both for threat assessment and for disrupting the innovation process.66 Specific strategies may include disrupting tacit knowledge exchange, addressing ungoverned spaces and isolating charismatic or influential leadership. Threat assessment models must include the preconditions for innovation, combined with indicators of WMD/E development.

Disrupting innovation through information activities

Where traditional counter-WMD activities have focussed on the supply side of the supply/demand equation, there has been a lack of coherent effort aimed at addressing the demand for catastrophic weapons. Part of the appeal of WMD to would-be terrorists stems from an inflated and almost irrational fear of their employment — the Hollywoodesque ‘nightmare’ of WMD paired with the unrestrained aspirations of terrorism. This catastrophic narrative is underpinned by the political use of WMD as an umbrella term to refer to a wide range of threats to influence the target audience. Information activities can address the perceived cost benefits of catastrophic terrorism.

It is clear that rationality is susceptible to influence by controlling the information presented and by exploiting uncertainty over future events. A decision to pursue a course of action involves ‘guesses about future consequences of current actions and guesses about future preferences for those consequences.’67 Subjective preferences and consequences are affected by uncertainty, complexity, imperfect information and imperfect decision-making processes. Information activities can influence opposition decision-making calculus by increasing the perception of attack costs, while decreasing the perception of attack benefits. Information activities include ‘shaping and influencing (at the strategic level); information operations (at the operational level); and inform and influence actions (at the tactical level).’68

An effective information campaign as part of a broader influence campaign can contribute to the disruption of terrorist innovation. Information actions can be developed to counter the existing narrative of the ease of WMD production and employment, influence those supporters who can be deterred, and discredit WMD/E as a method of attack. For example, Schelling believes Islamic terrorists can be deterred from the use of bio- weapons if convinced that the weapons will also infect and kill many Muslims in the Middle East.69 Further specific opportunities may exist in degrading the value placed on tacit information and by isolating charismatic and influential leadership in terrorist groups. Information activities must be characterised by nuanced cultural and organisational understanding.

Social network analysis as a tool to disrupting information flows in dark networks

From an interdiction perspective, understanding the terrorist network’s structure, function, culture and organisational goals is critical. In Iraq in 2003, Stanley McChrystal realised the shortcomings of mapping terrorist organisations via traditional hierarchies of commanders, lieutenants and foot soldiers. In contrast to previous wars, the enemy was agile: ‘money, propaganda and information flowed at alarming rates, allowing for powerful, nimble coordination’ with tactics changing almost simultaneously in different cities.70

To overcome this perceived shortcoming, social network analysis has grown in influence and become a ‘collection of theories and methods that assumes that the behaviour of actors (whether individuals, groups, or organizations) is profoundly affected by their ties to others and the networks in which they are embedded.’71 Social and trust networks are influential in demonstrating how disaggregated dark networks function. For example, it has been asserted that US detention facilities in Iraq assisted in the formation of ISIS.72

Although social network analysis is most often regarded as useful in identifying the centrality of a network (which could be considered a proxy for leadership), it also has an important role in quantitatively identifying other social network functions such as clusters, liaison functionaries, and key personnel that enable networks to function.73 Where traditional counter- leadership and counter-network operations tend to target strong ties within a network, in the context of innovation, weak ties may be more influential than strong ties. This is supported by research that has revealed that the random removal of a weak tie within a network does more ‘damage’ than the removal of a strong link (the assertion arguing that strong links are easily replicated by other linkages within the strong network).74 For innovation, weak ties act as information bridges to entirely ‘new’ resources (including information), whereas strong linkages tend to be more insular. In terms of adoption of innovation, it has been found across a number of studies that early adopters of controversial innovations are most likely to be marginal members of groups, whereas less controversial innovations (proven techniques) are more likely to be adopted by those central to a group.75

Identifying personnel who enable innovation may rely on the discovery of ‘weak ties’. This is supported by theoretical research in which destabilising activities have been applied against loosely aligned cellular structures using social network analysis techniques revealing that strategies addressing ‘connections between agents are not sufficient. One needs to take into account properties such as knowledge and resource distribution.’76 A campaign of disrupting innovation within a decentralised terrorist network may represent a significant departure from traditional counter-leadership operations.

Currently Australia is in a similar position to the US military.77 Despite large quantities of available data, the ADF lacks the doctrine, terminology, training, risk assessment methodology, information systems and institutional knowledge to effectively inform military options using social network analysis. Social network analysis is generally considered synonymous with social networking software programs rather than with the quantitative tools that depict information flows. Education and doctrine must be institutionalised to leverage the tools available through social network analysis and to utilise its value in intelligence-led operations. Application of social network analysis- based destabilisation techniques must be developed through practical application, with destabilisation strategies driving information collection requirements.

Conclusion

The assumption underpinning existing proliferation controls is that a small number of states have the technology to pursue the production of WMDs and, by inference, the ability to control their dissemination. In the information age, and within the context of increased industrial applications for this technology, this monopoly no longer exists and the threat from WMD/E is generally considered to be rising. This threat (associated with dual-use commodities, the attributes of new terrorism and broad strategic trends) must be considered within Defence’s strategic planning. The various perceptions and definitions of WMD have created ambiguity over certain types of catastrophic weapons. A concept must be developed to mitigate the threat from WME and guide capability development efforts. While many of the base capabilities exist through Defence’s role in counter-WMD, small changes to existing concepts will assist in disrupting the threat from WME. Some of these changes involve only a subtle shift in focus: from WMD equipment to the innovation process generally; from punitive deterrence to culturally informed influence; and from interdicting weapons to addressing terrorism preconditions. The ability to increase Defence’s capacity to mitigate the rapidly evolving threat will depend on the establishment of relationships (internationally and domestically) with appropriate groups (such as academia, foreign security institutions, communities of interest, and technology companies).

The legacy paradigm inherited from counter-WMD efforts forms an effective basis for WMD/E prevention. The existing elements of counter-WMD (such as border control) should be retained in a future campaign with the integration of additional WMD/E prevention elements. The WMD/E ‘ways’ of horizon scanning and sensing (risk assessment), collective influence and disrupting innovation form an effective basis for integration into a single campaign. The means need to be integrated across the whole of government approach, via a renewed strategy similar to the 2005 Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade publication ‘Weapons of Mass Destruction – Australia’s Role in Fighting Proliferation: Practical Responses to New Challenges’. In the absence of a renewed publication, or additional guidance from the government, there are a number of areas organic to Defence that can assist in threat reduction. These changes do not necessarily detract from Defence’s key tasks and in many cases will have broad utility across a number of Defence objectives.

Endnotes

1 J.M. and B.J. Lutz, ‘How Successful Is Terrorism?’, 2009, at: www.forumonpublicpolicy. com/spring09papers/archives09/lutz.pdf (retrieved 10 September 2015).

2 The Hon J. Bishop, address to 2015 Sydney Institute annual dinner, 27 April 2015,

at: www.foreignminister.gov.au/speeches/Pages/2015/jb_sp_150427.aspx (retrieved 10 May 2015).

3 Nuclear terrorism is also an area to which much research has been devoted. However, the approaches in many cases for non-proliferation are significantly different while nuclear weapons and fissile material are generally governed by a series of separate treaties

and often have specific organisations dedicated to their control. In addition, nuclear enrichment technology is advancing comparatively slowly and presents increased opportunities for detection in comparison to chemical and biological programs. Chemical and biological weapons can be organically developed and the technology and expertise have widespread industrial applications as dual-use commodities. Radiological weapons (primarily available through the diversion of existing radiological sources) will not be specifically addressed in this article.

4 W.S. Carus, Defining “Weapons of Mass Destruction”, Occasional Paper No. 8, 2012, p.

5, at: http://wmdcenter.dodlive.mil/files/2006/01/OP8.pdf (retrieved 10 December 2014).

5 J. Zaleski, ‘New Types and Systems of WMD: Consideration by the CD’, 2011, at: www. unidir.org/files/publiications/pdfs/new-types-and-systems-of-wmd-consideration-by-the- cd-374.pdf (retrieved 15 March 2015).

6 R. Bongiovi, Statement of Major General Robert P. Bongiovi, USAF Acting Director

DTRA before Emerging Threats and Capabilities Subcommitee, 12 July 2001, at: www. globalsecurity.org/military/library/congress/2001_hr/010712bongovi.pdf (retrieved 10 April 2015). This definition encompasses a broad breadth of WMD threats, both in the possible range of technology considered to be WMD and also in terms of lethality (the USS Cole attack killed 17 US personnel and involved an estimated 200 to 300kg of conventional high explosives).

7 Commonwealth of Australia, Weapons of Mass Destruction (Prevention of Proliferation) Act 1995, at: http://www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/C2010C00112 (retrieved 2 Feburary 2014).

8 Joint Chiefs of Staff, ‘National Military Stratefy of the United States of America’, 2004, p.1,

at: http://www.defense.gov/news/mar2005/d20050318nms.pdf (retrieved 5 May 2015).

9 Department of Defense, ‘The National Defense Strategy of the United States of America’, 2005, p. 2, at: http://www.defense.gov/news/Apr2005/d20050408strategy.pdf (retrieved

15 March 2015).

10 S. Leavitt and B. Kesler, ‘Weapons of Mass Effect’, Strategic Insights, Issue 10, No. 2, 2011, p. 11. There remains a lack of consensus over the lethality required for an attack to be considered an WME attack, ranging from 25 (C. Quillen, ‘A Historical Analysis of Mass Casualty Bombers’, Studies in Conflict and Terrorism, Issue 25, 2002, pp. 279–92) to 1000 (W.C. Yengst, ‘Dynamics of next generation WMD and WME Terrorism’ in L.A. Dunn (ed.), Next Generation of Mass Destruction and Weapons of Mass Effects Terrorism, Defense Threat Reduction Agency, Fort Belvoir, Virginia, 2008, section 2-5, p. 4).

11 Modernisation and Strategic Planning Division, The Future Land Warfare Report, Defence Publishing Service, Canberra, 2014, p. 13.

12 Homeland Security Advisory Council, ‘Preventing the Entry of Weapons of Mass Effect into the Unitied States’, January 2006, p. 4, at: http://www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/hsac_ wme-report_20060110.pdf (retrieved 10 December 2014).

13 L.A. Dunn, ‘Dynamics of Next Generation WMD and WME Terrorism’ in L.A. Dunn (ed.), Next Generation of Mass Destruction and Weapons of Mass Effects Terrorism, Defense Threat Reduction Agency, Fort Belvoir, Virginia, 2008, p. 17.

14 Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) ‘Chemical Weapons Convention’, at: https://www.opcw.org/chemical-weapons-convention/ (retrieved 10 July 2015).

15 P.F. Walker, ‘Syrian Chemical Weapons Destruction: Taking Stock and Looking Ahead’, 2014, at: http://www.armscontrol.org/ACT/2014_12/Features/Syrian-Chemical-Weapons-

Destruction-Taking-Stock-And-Looking-Ahead (retrieved 2 July 2015).

16 OPCW, ‘OPCW Fact Finding Mission: “Compelling Confirmation” That Chlorine Gas Used as a Weapon in Syria’, 2014, at: http://www.opcw.org/news/article/opcw-fact-finding- mission-compelling-confirmation-that-chlorine-gas-used-as-weapon-in-syria/ (retrieved 1

August 2015).

17 R. Jackson, A. Ramsay, C. Christensen, S. Beaton, D. Hall, and I. Ramshaw, ‘Expression of Mouse Interleukin-4 by a Recombinant Extromelia Virus Suppresses Cyctolytic Lymphocyte Responses and Overcomes Genetic Resistance to Mousepox’, Journal of Virology, Issue 75, No. 3, 2001, pp. 1205–10.

18 M. Selgelid and L. Weir, ‘The Mousepox experience’, EMBO Reports, Vol. 1, 2010, pp. 18–24.

19 G.B. Roberts, Arms Control without Arms Control: The Failure of the Biological Weapons Convention Protocol and a New Paradigm for Fighting the Threat of Biological Weapons, US Air Force (USAF) Institute for National Security Studies, USAF Academy, Colorado, 2003; R.J. Mathews, ‘WMD Arms Control Agreements in the Post-September 11 Security Environment: Part of the counter-terrorism Toolbox’, Melbourne Journal of International Law, Vol. 8, 2007, pp. 292–310.

20 J. Joseph, ‘The Proliferation Security Initiative: Can Interdiction Stop Proliferation?’, Arms Control Today, Issue 34, No. 5, 2004, pp. 6–13.

21 Weapons of Mass Destruction Commission, Weapons of Terror: Freeing the World of Nuclear, Biological, and Chemcial Arms, Stockholm, Sweden, 2006, p. 54.

22 P. Foz, Proliferation Security Initiative: Chairman’s Statement at the Fifth Meeting, 2004,

at: www.2001-2009.state.gov/t/isn/rls/other/30960.htm (retrieved 27 July 2015).

23 Joseph, ‘The Proliferation Security Initiative: Can Interdiction Stop Proliferation?’, p. 8.

24 J. Garvey, ‘The International Institutional Imperiative for Countering the Spread of Weapons of Mass Destruction: Assessing the Proliferation Security Initiative’, Journal of Conflict and Security Law, Vol. 10, 2005, p. 131.

25 United Nations Security Council, Resolution 1540, 28 April 2004, at: http://www.un.org/

en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/RES/1540 (retrieved 10 May 2015).

26 I. Khripunov, ‘A Work in Progress: UN Security Resolution 1540 After 10 Years’, Arms Control Today, May 2014, p. 39.

27 C. Chyba, ‘Biotechnology and the Challenge to Arms Control’, Arms Control Today, Issue 36, No. 8, 2006, p. 11.

28 National Agency for Export Controls (2005), http://www.australiagroup.net/en/20years. pdf, p.7

29 S. Zukang, Statement by Mr Sha Zukang at the Seventh Annual Carnegie International Non-proliferation conference, 1999, at: http://www.china-un.ch/eng/cjjk/cjjblc/jhhwx/ t85313.htm (retrieved 6 July 2015).

30 R.A. Zilinskas and P. Mauger, Biotechnology E-commerce: A disruptive Challenge to Biotechnology Arms Control, James Martin Center for Non-proliferation Studies, Monterey, CA, 2015.

31 McKinsey & Company, Urban world: cities and the rise of the consuming class, 2012, p.17, at: www.mckinsey.com (retrieved 1 March 2015).

32 A.T. Kearney, Chemical Industry Vision 2030: A European Perspective, 2012, at: https://www.atkearney.com/documents/10192/536196/

Chemical+Industry+Vision+2030+A+European+Perspective.pdf/7178b150-22d9-4b50- 9125-1f1b3a9361ef (retrieved 10 March 2015).

33 KACST, Strategic Review of the Biotechnology landscape, October 2013, at: http://www. kacst.edu.sa/en/about/publications/Other%20Publications/STRATEGIC%20REVIEW%20 OF%20THE%20BIOTECHNOLOGY%20LANDSCAPE.pdf (retrieved 3 March 2015).

34 N. Tishler, ‘C, B, R, or N: The influence of Related Industry on Terrorists’ Choice of Unconventional Weapons, Canadian Graduate Journal of Sociology and Criminology, Issue 2, No. 2, 2013, pp. 52–71.

35 Commonwealth of Australia, ‘Australia’s National Security 2003: A Defence Update’, p.

11, at: http://aseanregionalforum.asean.org/files/library/ARF%20Defense%20White…

Papers/Australia-2003.pdf (retrieved 15 March 2015).

36 M. Weber, ‘Politics as a Vocation’ in From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, H.H. Gerth

and C. Wright Mills (trans.), Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1946, p. 78.

37 ‘Australia’s National Security 2003: A Defence Update’, p. 15.

38 C. Arena, ‘4 Reasons Why Exponential Technologies Are Taking Off’, 2014, at: www. fastcoexist.com/3034200/4-reasons-why-exponential-technologies-are-taking-off (retrieved 27 July 2015).

39 J. Arquilla, ‘To Build a Network’, Prism, Issue 4, No. 1, 2014, pp. 22–33.

40 J.M. Bale and G. Ackerman, ‘Recommendations on the Development of Methodologies and Attributes for Assessing Terrorist Threats of WMD Terrorism’, 2004, p. 45, at: www.courses.cs.washington.edu/courses/csep590/05au/readings/Bale_Ackerm… FinalReport.pdf (retrieved 10 May 2015).

41 G. Michael, Lone Wolf Terror and the Rise of Leaderless Resistance, Vanderbuilt University Press, Nashville, Tennessee, 2012, p. 115.

42 National Commission on Terrorism, Countering the Changing Threat of International Terrorism, Report of the National Commision on Terrorism, US government, Washington DC, 2000, p. 2.

43 Department of Defence, Defending Australia in the Asia Pacific Century: Force 2030, Australian government, Canberra, 2009, pp. 23–24.

44 P. Schwartz, Inevitable Surprises, Gotham Books, New York, 2004.

45 Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Weapons of Mass Destruction: Australia’s Role in Fighting Proliferation: Practical Responses to New Challenges, Australian government, Canberra, 2005, p. 26.

46 A.R. Morral and B.A. Jackson, Understanding the Role of Deterrence in Counterterrorism Security, RAND Corp, Santa Monica, CA, 2009; M. Kroenig and B. Pavel, ‘How to Deter Terrorism’, The Washington Quarterly, Issue 35, No. 2, 2012, pp. 21–36; R.F. Trager and

D.P Zagorcheva, ‘Deterring Terrorism: It can be done’, International Security, Issue 30, No. 3, 2005, pp. 87–123.

47 J.M. Smith, ‘Strategic Analysis, WMD Terrorism, and Deterrence by Denial’ in A. Wenger and A. Wilner (eds.), Deterring Terrorism: Theory and Practice, Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA, 2012, pp. 159–79; L.A. Dunn, ‘Influencing Terrorists’ WMD Aquisition and use Calculus’, 2008, at: http://www.stanleyfoundation.org/publications/working_papers/ usnpr_papers/NEXTGE~1.PDF (retrieved 10 March 2014); B. Roberts, ‘Deterrence and WMD Terrorism: Calibrating its Potential Contributions to Risk Reduction’, 2007, at: www.dtic.mil/get-tr-doc/pdf?AD=ADA470305 (retrieved 2 May 2015); D.P. Auerswald, ‘Deterring Nonstate WMD Attacks’, Political Science Quarterly, Issue 121, No. 4, 2006,

pp. 543–68.

48 E. Adler, ‘Complex Deterrence’ in T.V. Paul, P.M. Morgan, and J.J. Wirtz (eds.), Complex Deterrence: Strategy in the Golden Age, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2009,

p. 98.

49 J. Hawkins, ‘Amphibious Warfare a discussion paper, in Projecting Force: The Australian Army and Maritime Strategy’, 2010, p. 40. at: http://army.gov.au/~/media/Files/ Our%20future/LWSC%20Publications/SP/sp317ProjectingForceAlbert%20Palazzo%20 Antony%20Trentini%20Jonathon%20Hawkins%20Malcolm%20Brailey.pdf (retrieved 28 July 2015). Sea basing ‘… facilitates STOM [ship to objective manoeuvre] and distributed operations and provides protected, flexible and responsive support. Sea basing mitigates land threats by preserving the majority of command and control and logistic resources at sea.’ ‘This concentrates focus on the objective by the projection of combined arms, by both surface and air means, directly from the sea, dislocating the adversary both in time and space.’ See Hawkins, p. 40.

50 US Department of Defense, ‘Deterrence Operations Joint Operating Concept’, 2006, p. 17, at: http://www.dtic.mil/doctrine/concepts/joint_concepts/joc_deterrence.pdf (retrieved 10 September 2015).

51 Department of Defence, Defence White Paper 2013, Defence Publishing Service, Canberra, p. 26.

52 J. Berger, ‘War on Error: We’re fighting al Qaeda like a terorist group. They’re fighting us as an army’, 2014, at: www.foreignpolicy.com/2014/02/05/war-on-error (retrieved 10 September 2015).

53 M. Abd al Qadir, ‘Call to Global Islamic Resistance’, 2005, pp. 25–26, at: https:// ia800304.us.archive.org/27/items/TheGlobalIslamicResistanceCall/The_Global_Islamic_ Resistance_Call_-_Chapter_8_sections_5_to_7_LIST_OF_TARGETS.pdf (retrieved 15 August 2015). These stages are not dissimilar to Mao Tse Tung’s revolutionary warfare, albeit sequenced differently.

54 Some authors have argued that ISIS (for example) is not a terrorist organisation at all but instead is a proto or pseudo state, and that addressing the problem in terms of terrorism limits the effectiveness of the response see B. Lia, ‘Understanding Jihadi Proto States’, Perspectives on Terrorism, Issue 9, No. 4, 2015, pp. 31–41.

55 M. Abrahms, ‘Why Terrorism Does Not Work’, International Security, Issue 31, No. 2, 2006, pp. 42–78.

56 Lutz and Lutz, ‘How Successful Is Terrorism?’, p. 17.

57 M. Crenshaw, ‘The Causes of Terrorism’ in C.W. Cegley (ed.), The New Global Terrorism: Characteristics, Causes, Controls, Prentice Hall, New Jersey, 2003, p. 98.

58 M. Quinlan, ‘Deterrence and Deterrability’, Contemporary Security Policy, Issue 25, No. 1, 2004, p. 14.

59 D. Byman, ‘Passive Sponsors of Terrorism’, Survival, Issue 47, No. 4, 2005, p. 117.

60 R.J. Pranger and D.R.Tahtinen, Toward a realistic military assistance program, American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, Washington, 1974, p. 21.

61 A. Dolnik, Understanding Terrorist Innovation: Technology, tactics and global trends, Routledge, New York, NY, 2007, p. 6.

62 Ibid., p. 13.

63 Crenshaw, The Causes of Terrorism, pp. 383–84.

64 Adapted from causes listed in Crenshaw, ibid. and G. Ackerman, ‘Understanding Terrorist Innovation through the broader innovation context’ in M.J. Rasmusen and M.M. Hafez (eds.), Terrorist Innovations in Weapons of Mass Effect: Preconditions, Causes and Predictive Indicators, DTRA, FT Belvoir, VA, 2010, pp. 50–84.

65 V.H. Asal, G.A. Ackerman and R.K. Rethemeyer, ‘Connections Can Be Toxic: Terrorist Organizational Factors and the Pursuit of CBRN Weapons’, Studies in Conlict and Terrorism, Vol. 35, 2012, pp. 229–54; G.A. Ackerman, M. Johns, M.K. Binder, J.M. Bale, V. Asal, R.K. Rethemeyer and A. Murdie, ‘Anatomizing Chemical and Biological Non-State Adversaries’, 2014, at: https://calhoun.nps.edu/bitstream/ handle/10945/46068/CB%20Adversary%20Deliverable%201.1%20-%20Final%20 Report.pdf?sequence=4&isAllowed=y (retrieved 12 September 2015).

66 Ackerman, ‘Understanding Terrorist Innovation through the broader innovation context’.

67 J.G. March, ‘Bounded Rationality, Ambiguity, and the Engineering of Choice’, The Bell Journal of Economics, Issue 9, No. 2, 1978, p. 589.

68 Land Warfare Development Centre, Operations Series ADDP 3.13 Information Activities, 2013, p.1-3, at: www.defence.gov.au/FOI/Docs/Disclosures/330_1314_Document.pdf (retrieved 26 September 2015).

69 Kroenig and Pavel, How to Deter Terrorism, p. 28.

70 S. A. McChrystal, ‘It takes a Network: The new front line of modern warfare’, 2011, at: www.foreignpolicy.com/2011/02/21/it-takes-a-network/ (retrieved 2 September 2015).

71 S.F. Everton, Structural Analysis in the Social Sciences: Disrupting Dark Networks, Cambridge Press, New York, 2012, p. 5; W. de Nooy, A. Mrvar and J. Batagel, Exploraratory Social Network Analysis with Pajek, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2005, p. 5.

72 B. Parks, ‘How a US prison Camp Helped create ISIS’, New York Times, 30 May 2015, at: http://nypost.com/2015/05/30/how-the-us-created-the-camp-where-isis-was…

73 Everton, Structural Analysis in the Social Sciences: Disrupting Dark Networks, pp. 397–403.

74 M. Granovetter, ‘The Strength of Weak Ties’, American Journal of Sociology, Issue 73, No. 6, 1973, p. 1366.

75 M. Becker, ‘Sociometric Location and Innovativeness’, American Sociological Review, Vol. 35, 1970, pp. 267–82; E. Rogers, Diffusion of Innovations, Free Press, New York, 1962.

76 M. Tsevetovat and K. Carley, ‘Structural Knowledge and Success of Anti-Terrorist Activity: The Downside of Structural Equivalence’, Journal of Social Structure, Issue 6, No. 2, 2005.

77 J. Morganthaler and B. Giles-Summers, ‘Targeting Social Network Analysis in Counter IED Operations’, 2011, at: https://calhoun.nps.edu/bitstream/handle/10945/5703/11Jun_ Morganthaler.pdf (retrieved 10 September 2015); D. Knoke, ‘“It takes a network”: The Rise and Fall of Social Network Analysis in U.S. Army Counterinsurgency Doctrine’, Connections, Issue 33, No. 1, 2013, pp. 2–10.