Abstract

Social media and strategic communication sit at the heart of the war of ideas between the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) and the West. The West is critically vulnerable to ISIL’s use of social media, shrewdly exploited in the recruitment of potential jihadists. This article argues that the Western world is losing the digital propaganda war waged by ISIL. At the strategic level, ISIL plans, synchronises and coordinates its social media efforts. Commanders provide operational updates and select content relevant to their strategic needs. From the battlefield, Western recruits tweet predominantly in their native language. Disseminators residing in the West and not officially aligned with ISIL, share and pass on ISIL’s propaganda. These proxy disseminators perform the vast majority of ISIL’s strategic narrative propagation. ISIL uses social media technologies that make the discovery and tracking of its recruitment propaganda difficult, exploiting the ‘deep web’ and ‘dark web’, severely hampering Western tracking agencies’ efforts to identify and isolate it. This article concludes that the West’s qualified moderate voice must be legitimised, encouraged and empowered to win the war of ideas. To do this the West must reform its strategic communication approach; it must comprehensively increase the volume of proactive participation in the ideological discourse conducted within the social media space.

Introduction

Extremist Islam’s twenty-first century iteration of jihad1 against the West is a war of ideas with the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) placed strategically at the vanguard.2 Central to ISIL’s jihad is strategic communication through social media, particularly Twitter. This communication is deliberately designed to persuade the entire global community of Muslims, and particularly its youth, bound together by ties of religion and referred to in this article as ‘Ummah’, to join the jihad. ISIL’s ‘methodical and planned’ use of social media in its recruitment to the war of ideas represents a major threat to the West.3 Essential to this recruitment are those globally diffuse supportive digital natives of the virtual Ummah who act as message disseminators and are each a pivotal part of an inbuilt redundancy network design. It is in this sense that ISIL has deftly turned the information age to its distinct advantage, mastering the use of social media and its connected technology as a formidable information weapon that mobilises grassroots support.

Significantly, globalisation in the information age has resulted in an ongoing detribalisation of the West and a retribalisation of the Ummah. Detribalisation acts to effectively dilute the West’s dominant paradigms, while retribalisation is empowering the Ummah. ISIL’s narrative is informed by an ancient religious and cultural memory, one that draws on Islam’s history of protecting its ideology and traditions. The West’s counter-narrative is influenced by a modern secular memory, induced by democracy and globalisation.

ISIL’s jihad across the borders of Syria and Iraq is an extension and evolution of the war of ideas that is rooted in opposing eschatological cultural narratives, their ideological dichotomy one of ultimate ends.4 On one side is ISIL’s utopian desire for Islamic purity, encompassed by a dominant Islam emanating from a caliphate grounded in sharia law.5 On the other side is the West’s concept of democracy, globalisation and the universality of human rights.6 ISIL maintains Islam’s traditional extremist strategic narrative, albeit with an updated amplification more effectively propagated through social media.

ISIL and the social media threat to the West

Social media consists of Internet web pages and applications such as Twitter, YouTube, Facebook, Flickr and many more. It is an interactive model of communication that facilitates a two-way exchange of information between the broadcaster and recipient, but it also blurs the boundaries of the more usual methods of mediated creation of meaning. It allows users to create and share digital content, while simultaneously discovering and interacting with like-minded audiences. Social media’s significance and value to ISIL lies in its ability to increase message dissemination. Its ability to find and galvanise like-minded audiences extends well beyond previous two-way communication models and is its primary method of influence, particularly among potential recruits to jihad within the West’s youth.7 In essence, social media allows ISIL to compress the time and space within which it interacts with potential recruits, therefore amplifying the intent and effects of its strategic narrative.8

ISIL’s use of social media is a threat to the West for diverse, yet interrelated reasons. The information age and social media’s technology, its audiences, system, related jurisprudence and ability to shape perception, are all cleverly employed by ISIL against the West in the war of ideas.

Technology and audience

Access to social media technology is cheap and facilitated by no more than a simple power supply (see Figure 1).9 The simplicity of use and widespread nature of its technology means that ISIL’s propaganda dissemination is lateral and almost instantaneous.10 Information spreads broadly and quickly among users and audiences with few geographical constraints.11 ISIL’s globally diffuse supporters and disseminators are in fact each part of an inbuilt redundancy network designed to ensure that any muting of a supporter’s messaging does not curtail information spread.12 This makes it difficult, if not impossible, for the West to prevent ISIL distributing propaganda.

ISIL’s manipulation of technology is well suited to its target audience of potential Western recruits, the majority of whom are ‘barely out of high school’,13 perceive themselves as socially marginalised14 and are therefore readily receptive to ISIL’s strategic narrative. These potential recruits are digital natives15 of the virtual Ummah16 — individuals who are immersed and fluent in the use of social media and who ‘think and process information fundamentally differently from their predecessors’.17 Their changed thinking pattern has made each of them targetable ‘netizens’,18 individuals who are globally distributed, but instantly digitally connectable, and therefore easily accessible to ISIL and their recruitment tactics. Catalysed by their own perception of marginalisation, each ‘contribute[s] to the whole intellectual and social value and possibilities’ of ISIL’s strategic narrative, which is aimed at mobilising a globalised virtual Ummah to jihad.19

Figure 120

Globalisation and mediated memory

One consequence of globalisation in the information age has been the West’s ongoing detribalisation, with users now possessing an even greater ability to access and process knowledge from across the world.21 In other words, global information access in the digital era is facilitating more diverse views and opinions within the West that challenge dominant Western paradigms, and which serve to erode a consensus that relies on a ‘sense of identity, belonging and cause’.22 Conversely, this same information-age globalisation is enabling the virtual Ummah’s retribalisation23 from a grassroots level,24 allowing both ISIL and its potential extremist recruits to easily engage in a discourse that challenges the West’s dominant ideological platform of secular democracy. For them, social media is facilitating ‘the perfect place [as] individuals to express themselves while claiming to belong to a community to whose enactment they contribute, rather than being passive members in it’.25

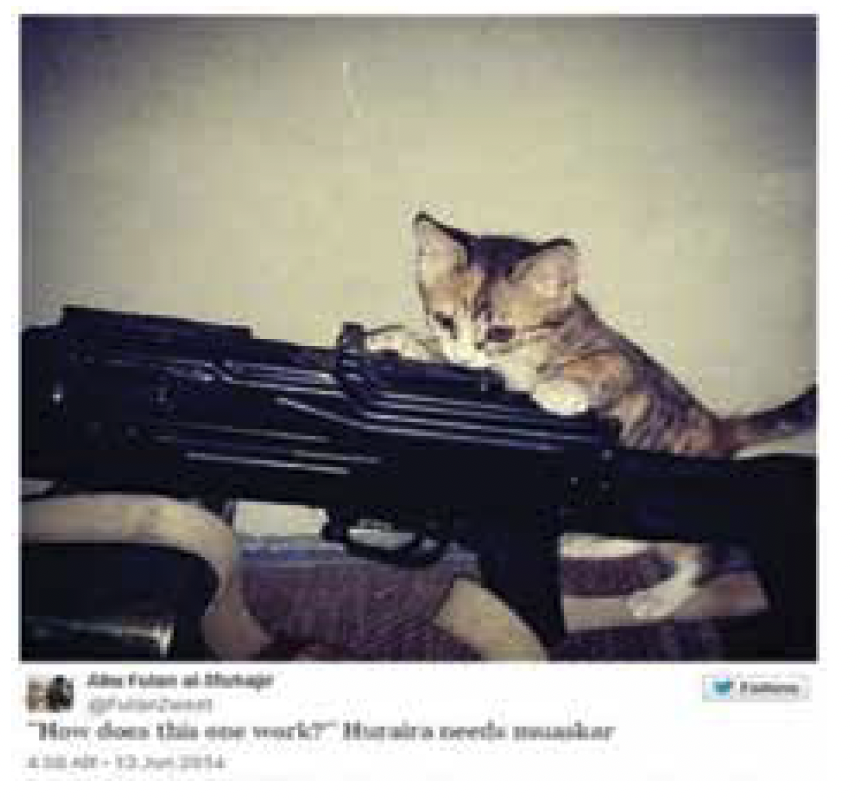

Through social media then, ISIL mediates the Ummah’s memory. By contextualising history’s verifiable facts and drawing out the abstract truths, ISIL claims its jihad is informed, re-imagining the past and connecting with the present in ways that portray history as more than the accumulation of documented events.26 Simple content is used to link traditional memory with the ISIL message. A prime example is ISIL’s use of cat images in its Twitter content (Figure 2). According to several Koranic references, the prophet Mohammad is said to have loved and cared for cats.27 The text in Figure 2 refers to Huraira, perhaps a reference to Abu Hurairah, a historical friend of the prophet Mohammad, also a cat lover and a master Hadith28 storyteller.29 ISIL’s use of the cat in battlefield settings conveys the memory of divinity, directly invoking Islamic traditions, values and beliefs.

Figure 230

ISIL’s subversion of Western narratives

ISIL’s use of social media has enabled it to circumvent Western media’s traditional role in communication, thereby providing it greater narrative control over its messaging. In the 1950s, David Manning White postulated that news published in traditional print media was determined by those with the power to decide — the journalist, the editor or the publication’s owner.31 The rise of television news, although less structured, still reflected this model. Power models in social media are not as clear.

Circumventing the gatekeeper

There is a long-standing recognition that media heavily influences what a society considers its priorities.32 ISIL’s use of social media allows it to exploit these traditional models, bypassing the traditional media’s gatekeeper function and creating its own agenda-setting action among its potential recruits. ISIL has forcefully illustrated this point by directly attacking the West’s media industry with consecutive beheadings of American journalists James Foley and Steven Sotloff in August and September 2014.33 These symbolic acts serve ISIL in three ways, while also powerfully demonstrating its threat to the West. First, ISIL sets the agenda by broadcasting the acts through its social media network. These are then widely reported by Western media outlets. Second, by killing journalists ISIL demonstrates that it does not need the traditional media model to disseminate its message. Third, by dressing the victims in orange jumpsuits similar to those used for jihadist detainees at Guantanamo Bay, ISIL appeals to its audience’s sense of retribution against the perceived wrongs perpetrated by the West.

ISIL’s use of social media effectively manipulates and subverts the West’s traditional news media practices to communicate its narrative. Western media may value objectivity and balance, but news value is often determined by shocking content. The old adage ‘if it bleeds it leads’ originated in the idea that news content that evokes fear and repugnance also ensures greater audience share. ISIL is well aware of this. It knows its fearful and repugnant content uploaded onto social media will be rebroadcast by the West’s media. It is also acutely aware that Western news media’s adherence to professional ethical requirements of objectivity and balance can also work in its favour. For example, in response to the call by 120 members of the British Parliament that the British Broadcasting Corporation use the term ‘Daesh’ in its news reporting rather than the Islamic State,34 Director General Tony Hall asserted that doing so would ‘bias their coverage’.35

ISIL social media global warriors: proxy disseminators

Despite the apparent lack of control over messaging in social media, ISIL’s strategic social media recruitment approach, driven by Twitter, allows it an extraordinary degree of control.36 ISIL’s message is effectively dispersed through an efficient network37 in which ‘individual and official [Twitter] accounts work in parallel and are tightly integrated’.38 At the strategic level, ISIL plans, synchronises and coordinates its social media efforts through its official al-Hayat Media Center.39 At regional levels throughout its area of operations, ISIL’s commanders provide operational updates and select content relevant to their strategic needs.40 From the battlefield, Western recruits tweet predominantly in their native language, providing simple coherence that can be effortlessly broadcast to the West.41 Finally, and most crucially, disseminators residing in the West and not officially aligned with ISIL share and pass on ISIL’s propaganda.42 These proxy disseminators account for the vast majority of ISIL’s strategic narrative propagation.43

Using Western principles: ‘lawfare’ and freedom of speech

Western jurisprudence is, in itself, a threat to the West in the face of ISIL’s social media. The term ‘lawfare’, coined in the 1990s by retired US Air Force Major General Charles Dunlap, is an operational focus or ‘way to apply legal pressure on the other side of a conflict ... which then potentially forces the enemy to defend themselves in multiple arenas’.44 Despite the West’s intelligent and legally nuanced understanding of lawfare, ISIL’s use of social media affords it a significant opportunity to appropriate the concept by staging events that, when digitally recorded and disseminated, will evoke an emotional response among potential recruits.

The following is an effective ISIL strategic communication or ‘lawfare’ operation facilitated by social media, adapted from an actual event45:

- The set-up: ISIL targets Western troops from the minaret of a mosque thereby violating international humanitarian law;

- The bait: Western troops return proportionate fire in accordance with international humanitarian law;

- Record it: ISIL digitally records the West’s response;

- Strategic communication: ISIL disseminates the recording via its social media network, highlighting the West’s attack on a holy Islamic site;

- Lawfare: an unofficial Western ISIL sympathiser presents the recording as evidence to a judicial forum under a false pretext;

- Recruitment effect: the probable failure of the legal proceeding further reinforces the perception of the West attacking Islam in the minds of potential recruits.

The West’s highly valued freedom of speech also presents a problem. Freedom of speech emerged from the liberal belief in the importance of ‘a space where the individual is free from social coercion’.46 Social media is also a space, but its digital nature creates challenges for freedom of speech and censorship laws. Legally proving ISIL-generated social media content being shared by unofficial ISIL proxy disseminators (or any individual who shares the content, including journalists) is seditious is extremely difficult. It would be farcical, for example, to assert in a court of law that the tweeting of a cat atop a Kalashnikov is an act of sedition.

Legal parameters aside, to effectively censor and block ISIL’s propaganda, the West must first be aware of its existence. The technology available to and utilised by ISIL’s social media practitioners makes the discovery of its recruitment propaganda difficult. ISIL’s social media network is designed to drive potential recruits to the deep47 and dark web,48 internet spaces that are ‘dynamically generated [that] standard search engines never find’.49 Sophisticated and expensive software is required to laboriously scour the deep web, with efforts continually frustrated by proxy disseminators simply changing their identity, shutting down sites and establishing new ones.50 Encryption software also makes detection increasingly difficult, with open-source software such as Freenet allowing users to share content anonymously.51 The sharing of content at close range is also almost undetectable through the use of Bluetooth PAN (personal area network) technology.52 Evidence suggests potential recruits share content between their hand-held devices on a ‘pocket-to-pocket’ basis.53

Promises and perception

David Galula provided a prescient warning in 1968 stating, ‘the insurgent [is] judged by what he promises, not by what he does ... the counterinsurgent [is] judged on what he does, not on what he says’.54 In other words, ISIL’s promise of a utopian Islamic caliphate, whether achievable or not, is an easier narrative to disseminate than that of the West. For the West, the measure of success lies in achieving tangible results within the bounds of liberal democratic norms. Among other things, effective strategic communication requires that perception is managed in some way. Social media, with its perception as user generated and the speed at which it can be disseminated assumes the guise of authenticity. Among potential recruits, ISIL’s use of social media as a platform creates an impression of content spontaneously produced and shared by jihadists on the battlefield. What is perceived as user-generated content is actually constructed to reflect truth and jihadists’ experiences. That the narrative is strategic rather than unmediated is hidden beneath constructed authenticity that belies the reality of ISIL’s purposefully designed narrative and controlled dissemination.

Narrative and counter-narrative

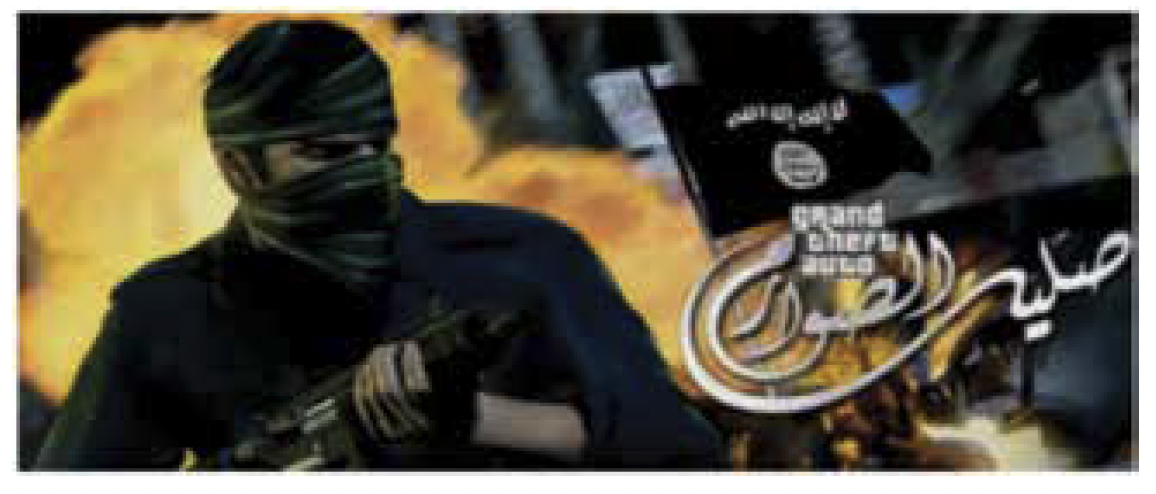

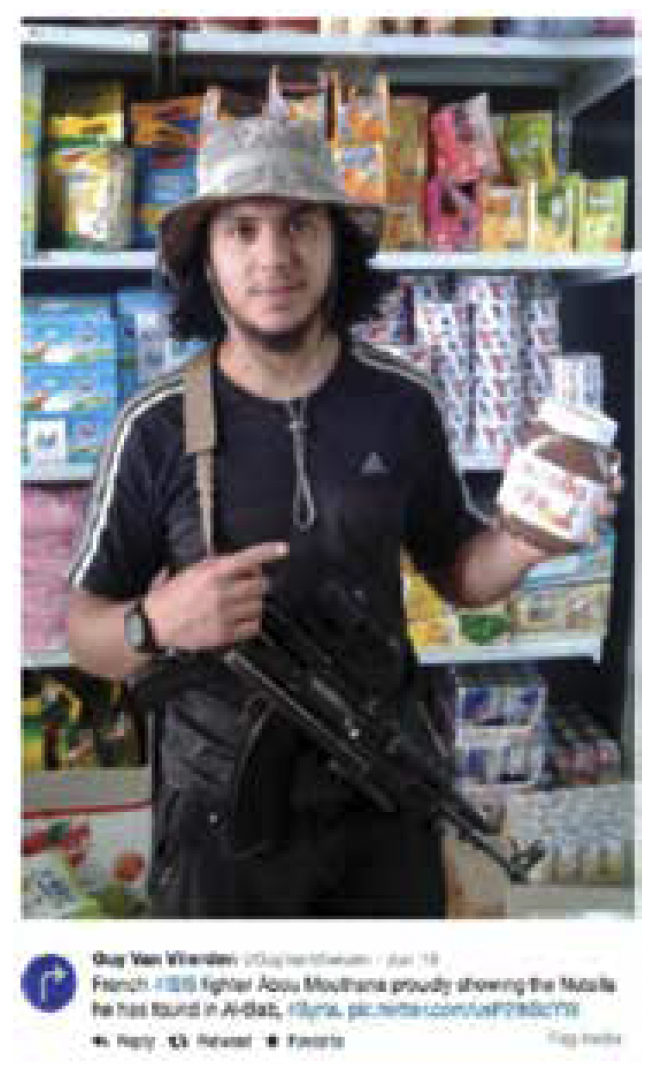

ISIL’s strategic narrative continues an extremist jihadi tradition that consists of five key messages55: Islam is under attack from the West; jihad is essential to defend Islam from attack; ISIL’s defence is piously correct and just; it is the duty of all Muslims to join the jihad; and finally, the re-establishment of a caliphate will secure Islam’s future. The narrative is informed by a rich and complex enmeshing of ideology, tradition and common sense.56 In what Ann Swidler describes as ‘culture shaping action’, ‘belief and ritual practice directly shape action for the community that adheres to a given ideology’.57 For ISIL and its potential recruits, the compelling ideology is Islam, the tradition is fighting the infidel or the West, and the common sense is that jihad is the natural path of Islam’s history. Importantly, ISIL’s audience of potential Western digital native netizens of the virtual Ummah informs its narrative in a modern way. For example, ISIL responds to its audience’s way of thinking through the use of video games (Figure 3), hoping that a targeted individual will perceive the potentially fatal choice to join the jihad as no more than a simple game, or that the life of a jihadist is normal and fun (Figure 4).

Figure 358

The West’s counter-narrative is informed by the nature of the West itself, which encompasses a diverse international community of nation–states grounded in an accepted liberal democratic paradigm that maintains the agreed international status quo. It comprises a multitude of key actions including counterterrorism, counterinsurgency, the prevention and restructuring of failed states, the targeting and disruption of terrorist funding, national interests and the free flow of trade.59 Secular democracy is its ideology, free trade and globalisation its tradition, and the right to freedom its common sense. To counter ISIL’s strategic narrative in the social media domain, the West, led by the United States, has launched a Twitter campaign known as #thinkagainturnaway. The campaign relies on the West’s self-perception of its ability to prevent recruits from joining the jihad through reason (Figure 5) and a common unity between the West and Muslim adherents (Figure 6).

Countering ISIL’s war of ideas can be achieved by attacking its social media centre of gravity. The West must recognise, appropriate and prioritise social media as its own formidable information weapon. It must introspectively reform its strategic communication approach and clearly delineate between the two separate digital native audiences of the West and the Ummah, detach their narratives and those who give them voice.

Figure 460

The West must begin to reverse its globalised, detribalising nature by retribalising its own audience. It must mobilise the majority to recognise that the luxury of liberal democratic secular freedom carries with it the quid pro quo of obligation — the obligation to actively defend and export liberal democracy’s ideals. With clarity, simplicity, common intelligibility and realistic interpretation, targeted social media content must evoke the imagination and actively promote its culture’s rewards.61

Figure 5 (courtesy of Twitter.com)

The West must recognise the tribalised virtual Ummah and acknowledge that Islam’s fate can only be decided by Islam’s faithful. To act differently will serve only to corroborate ISIL’s strategic narrative. The Ummah’s qualified moderate voice must be legitimised, encouraged and empowered to win its own war of ideas. To do this, it must comprehensively increase the volume of its proactive participation in the ideological discourse conducted within the social media space. To that end, the West’s counter-narrative’s status quo of counterterrorism, counterinsurgency, and prevention and restructuring of failed states is no longer relevant for ISIL. ISIL has moved beyond these confines. By force it has acquired land, created a space, established a presence, renewed an ancient ideology and garnered and projected power to become a nascent state coercively asserting its legitimacy. It must be offensively treated as such. The West’s narrative must be the narrative not simply a counter-narrative.

Figure 6 (courtesy of Twitter.com)

Conclusion

Social media and strategic communication are at the centre of the war of ideas between ISIL and the West. The West is critically vulnerable to ISIL’s use of social media due to its technology, its audiences, the system, its related jurisprudence and ability to shape perception, all of which are shrewdly worked by ISIL in the recruitment of potential jihadists. Significantly, ISIL’s recruitment strategy relies on those globally diffuse and supportive digital natives of the virtual Ummah who spread the message of jihad from within a network with an inbuilt redundancy.

In other words, the silencing of one or more supporters’ messages does not diminish information spread, making it difficult if not impossible for the West to prevent ISIL’s propaganda distribution. Most importantly, globalisation in the information age is facilitating a detribalisation of the West and a retribalisation of the Ummah. The dominant paradigms of the West are being diluted by its detribalisation while, conversely, the Ummah is being empowered by its retribalisation. ISIL’s narrative is informed by an antique religious and cultural recollection, one that appeals to Islam’s history of protecting its ideology and traditions. The West’s counter-narrative is progressed by a modern secular memory, persuaded by democracy and globalisation. The West and the moderate Ummah can win. However this is a victory that will be a long time in the making, expensive and difficult.

Endnotes

1 A war or struggle against unbelievers.

2 K. Payne, ‘Winning the Battle of Ideas: Propaganda, Ideology, and Terror’, Studies in Conflict and Terrorism, 32, 2009, p. 109.

3 P. Taylor, Munitions of the Mind: A History of Propaganda, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2003, p. 6.

4 D. Betz, ‘The Virtual Dimension of Contemporary Insurgency and Counterinsurgency’, Small Wars & Insurgencies, 19: 4, 2008, p. 522.

5 Payne, ‘Winning the Battle of Ideas’, p. 111.

6 Betz, ‘The Virtual Dimension of Contemporary Insurgency and Counterinsurgency’, p. 522.

7 D. Rand and A. Vassalo, Bringing the Fight Back Home: Western Foreign Fighters in Iraq and Syria, Policy Brief, Center for a New American Security, August 2014, p. 2, http://www.cnas. org/sites/default/files/publications-pdf/CNAS_ForeignFighters_policybrief.pdf.

8 D. Murthy, ‘Towards a Sociological Understanding of Social Media: Theorizing Twitter’,

Sociology, 46: 6, 2012, p. 1060.

9 J. Klausen, ‘Tweeting the jihad: Social media networks of Western foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq’, Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 2014, p. 8, http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/ 1057610X.2014.974948.

10 Ibid., p. 5.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Rand and Vassalo, ‘Bringing the Fight Back Home’, p. 2.

14 Ibid., p. 2

15 M. Prensky, ‘Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants: Part 1’, On the Horizon, 9: 5, 2001, p. 2.

16 O. Roy, ‘Headquarters of Terrorists is “Virtual Ummah”’, New Perspectives Quarterly, 2, 2010,

p. 42.

17 Prensky, ‘Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants’, p. 2.

18 M. and R. Hauben, Netizens: An anthology, 1993, http://www.columbia.edu/~rh120/.

19 Ibid.

20 Source: https://twitter.com/Fulan2weet/status/374579796858404865 (account shut down).

21 M. McLuhan and F. Quentin, War and peace in the global village, San Francisco: Hardwired, 1997, p. 374.

22 Betz, ‘The Virtual Dimension of Contemporary Insurgency and Counterinsurgency’, p. 515.

23 McLuhan and Quentin, War and Peace in the Global Village.

24 A. Appadurai, ‘Grassroots Globalization and the Research Imagination’, Public Culture, 12: 1, 2000, p. 3.

25 McLuhan and Quentin, War and Peace in the Global Village, p. 375.

26 T. Macaulay, ‘Essays. History’, Edinburgh Review, May 1828 in A. Ward, A Dictionary of Quotations in Prose, New York: Thomas Y. Crowell & Company, 1889, p. 248.

27 G. Geyer, When Cats Reigned Like Kings: On the Trail of the Sacred Cats, Kansas City: Andrews McMeel Pub., 2004, p. 4.

28 S. Dida contributed the term ‘Hadith’ to this paper in a personal communication, 27 October 2014.

29 A collection of traditions containing sayings of the prophet Muhammad which, with accounts of his daily practice (the Sunna), constitute the major source of guidance for Muslims apart from the Koran. See The Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition, J.A. Simpson and E.S.C. Weiner (eds), New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

30 R. Powell, ‘Cats and Kalashnikovs: Behind the ISIL Social Media Strategy’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 24 June 2014, http://www.smh.com.au/world/cats-and-kalashnikovs-behind- the-isil-social-media-strategy-20140625-zsk50. Courtesy of Twitter.com

31 D. White, ‘The “Gate Keeper”: A Case Study in the Selection of News’, Journalism Quarterly, 1950, http://www.aejmc.org/home/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/Journalism-Quarter…- White-383-90.pdf.

32 M. McCombs and D. Shaw, ‘The Agenda Setting function of Mass Media’, Public Opinion Quarterly, 36, Summer 1972, pp. 176–87.

33 B. LoGiurato and H. Walker, ‘ISIS Reportedly Executes Another American Journalist, Steven Sotloff’, Business Insider Australia, 3 September 2014, http://www.businessinsider.com.au/ steven-sotloff-isis-killed-2014-9. Proportionately, ISIL has executed more non-journalists. Their victims, now in the hundreds, include Sunni Iraqi Security Force members, aid workers and those generally opposed to their ideology.

34 Islamic State (IS) is the group’s own official title, having re-branded itself from ISIL to IS on thfall of Mosul in June 2014 and their announcement of an Islamic caliphate.

35 See, for example, http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3146855/We-fair-ISIS-BBC-refuses- MPs-demand-stop-using-Islamic-State-refer-terrorist-group.html.

36 Klausen, ‘Tweeting the Jihad’, p. 29.

37 Ibid., p. 2.

38 Ibid., p. 29.

39 Rand and Vassalo, ‘Bringing the Fight Back Home’, p. 9.

40 Ibid., p. 9.

41 Klausen, ‘Tweeting the Jihad’, p. 11.

42 Ibid., p. 11.

43 Ibid., p. 29.

44 G. Noone, ‘Lawfare or Strategic Communication’, Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law, 43: 1, 2010, p. 74.

45 Ibid., p. 82.

46 S. Sorial, ‘Sedition and the Question of Freedom of Speech’, Current Issues in Criminal Justice, 18: 3, 2007, p. 438.

47 M. Bergman, ‘White paper: The Deep Web: Surfacing Hidden Value’, The Journal of Electronic Publishing, 7: 1, 2001, http://quod.lib.umich.edu/j/jep/3336451.0007.104?view=text;rgn=main.

48 H. Chen, ‘Uncovering the Dark Web: A Case Study of Jihad on the Web’, Journal of The American Society for Information Science and Technology, 59: 8, 2008, p. 1347.

49 Bergman, ‘The Deep Web’.

50 Chen, ‘Uncovering the Dark Web’, p. 1348.

51 A. Beckett, ‘The Dark Side of the Internet’, The Guardian, 26 November 2009, http://www.theguardian.com/technology/2009/nov/26/dark-side-internet-fr….

52 S. Gold, ‘Terrorism and Bluetooth’, Network Security, 7: 5, 2011, p. 5.

53 Ibid.

54 D. Galula, Counterinsurgency Warfare: Theory and Practice, New York: Praeger, 2006, p. 9.

55 Betz, ‘The Virtual Dimension of Contemporary Insurgency and Counterinsurgency’, p. 520.

56 Ibid., p. 519.

57 A. Swidler, ‘Culture in Action: Symbols and Strategies’, American Sociological Review, 51: 2, 1986, p. 284.

58 Screen shot of an ISIL YouTube promotion of a soon-to-be-released video game.

See https://ludicgeopolitics.wordpress.com/2014/10/22/isis-to-use-videogame….

59 Betz, ‘The virtual Dimension of Contemporary Insurgency and Counterinsurgency’, p. 522.

60 Klausen, ‘Tweeting the Jihad’, p. 19.

61 K. Mulcahy, ‘The Cultural Policy of the Counter‐Reformation: The case of St. Peter’s’,

International Journal of Cultural Policy, 17: 2, 2011, p. 133.