The Army of the future will be characterised by the following qualities: extraordinary strategic agility, high-precision lethality and almost omniscient situational awareness. Our present C3 systems will have given way to sophisticated, yet robust, networks of sensors and shooters, seamlessly integrated throughout the battlespace.

- Lieutenant General Peter Leahy, AO, Chief of Army1

Whatever labels we adopt to describe future conflict, the reality of war will be complex and will combine the characteristics of pre-industrial-, industrial- and information-age combat. In order to be able to prevail in land warfare, the Australian Army must seek to identify the factors that it is likely to confront in a modern battlespace—a battlespace increasingly defined by information networks, advanced munitions and lethal weapons systems. At the same time, the Army must be aware that potential adversaries will also be adapting to new technologies and new operating conditions.

This article proposes the creation of an Expeditionary Task Force (ETF) based on a combined arms organisation and designed to fight in multidimensional conflict. It is argued that a smaller taskforce organisation should replace the industrial-age infantry brigade system. In contemporary security conditions, the ADF requires offshore or expeditionary capabilities in order to be able to execute contemporary multidimensional manoeuvre warfare. Yet our current industrial-age organisations are not optimised to respond rapidly to meet threats. In order to be able to respond rapidly in the 21st century, the Australian Army requires a reformed organisational structure that meets the challenges of complex, information-age warfighting.

Contours of Future Conflict

Despite the presence of highly advanced reconnaissance and surveillance capabilities and the use of networked, effects-based warfighting concepts, future conflict will not become a Nintendo-style activity. Rather, war is likely to remain a chaotic ‘Mad Max’ activity for, as Clausewitz reminds us, ‘war is ... an act of force to compel our enemy to do our will’.2 Friction, chance and danger will almost certainly continue to be pervasive elements throughout the future battlespace. Victory in such conditions will go to the side that best exploits uncertainty and chaos, and achieves decision superiority over an adversary.

Technology is, however, a great enabler in war, and in the modern 21st-century battlespace, networked operations are becoming more significant. As Admiral Arthur Cebrowski, the American architect of network-centric warfare, has stated: ‘the real fight is over sensors’.3 Because the majority of contemporary weapons systems have a greater range than their supporting sensors, if a target can be located, it can almost certainly be attacked. The increased vulnerability to a ‘sensor-shooter’ equation has led military organisations to try to adopt measures to deny or degrade an adversary’s sensor capability. In the future, rival forces are likely to compete in an effort to improve the effectiveness of their own sensors while neutralising those of their adversaries.

The future battlespace is likely to be non-linear, and both symmetric and asymmetric in character. In these conditions, older linear tactical concepts such as the Forward Edge of the Battle Area will no longer be applicable because land forces will use advanced communications and weapons systems to operate in dispersed depth.

The non-linear battlespace will also be characterised by simultaneous operational activity in the physical, temporal and cyber realms and will require the deployment of forces capable of delivering decisive effects.4 Such operations are likely to require smaller force units capable of self-protection and logistical self-sustainment. In many respects, it is not mass that counts, but the ability to deliver an effect, and in this respect the smaller the force, the more agile it can become and the quicker it can strike across the battlespace.

Land Operations in the 21st Century

The Australian Army’s keystone doctrine, The Fundamentals of Land Warfare, states that future operations will be based on defeating an enemy’s will.5 In this struggle, the contest over sensors will be a central element in the clash of wills and in achieving a ‘knowledge edge’ over an adversary. In addition, the land force must be able to operate concurrently across the spectrum of military conflict using an agile and adaptable organisation. The future land force must be capable of conducting warfighting, peace enforcement, peacekeeping and humanitarian relief, which may occur simultaneously. In most circumstances, the requirement for agility and versatility will be best achieved through the precise application of smaller, but highly trained and well-equipped forces. Conflict too has moved beyond state-versus-state contests. In the 21st century, we face merging forms of conflict—state, non-state, conventional and unconventional conflicts. Such conflicts will see armed forces confronted by highly complex missions in which modern high-technology may be used by militias, guerrillas and terrorists.

To retain agility in a chaotic battlespace, a land force must possess excellent tactical mobility. Forces must be capable of rapid dispersion or concentration in order to shape the battlespace and conduct joint precision fires utilising the air and sea assets that the ADF is projecting for the 2020 joint force.6 The future land force must, above all, seek to conduct effects-based operations rather than take ground. The operational focus must be on disruption rather than destruction, employing secure communications that are fully integrated with the networked systems architecture of a joint-force command. Finally, the future land force must be protected and sustained on operations, particularly if entry points such as ports and airfields are unavailable.

Towards a New Warfighting Organization: The ETF

The Australian Army of 2003 is essentially an industrial-age army, with some information-age additions. The Army’s current structure would still be recognisable to soldiers and officers of the World War II era. The battalion, brigade and division structures that continue to exist are products of what the American analyst, William S. Lind, has called ‘second generation’ warfare, where massed firepower and manoeuvre dominated.7 In order for the Australian Army to compete in the chaos of the information-age battlespace—where pre-industrial, industrial and post-industrial conflict methods may converge—a new warfighting organisation is required.

Given the small size of the ADF, the future Australian land force must achieve a combat effect that is disproportionate to its size. The central warfighting organisation of today’s Army—the brigade—must be transformed into a smaller but more lethal and precise instrument of combat: the ETF.

An ETF needs to be adopted as the principal warfighting organisation for the Australian Army by 2020. This new combat organisation would, over the next fifteen years, replace the light infantry and light mechanised brigades around which the Army is currently structured. Such a taskforce formation would be smaller than a brigade, with approximately 2000 troops, but it would be structured and equipped to achieve combat effects greatly superior to the Army’s current combat structures.

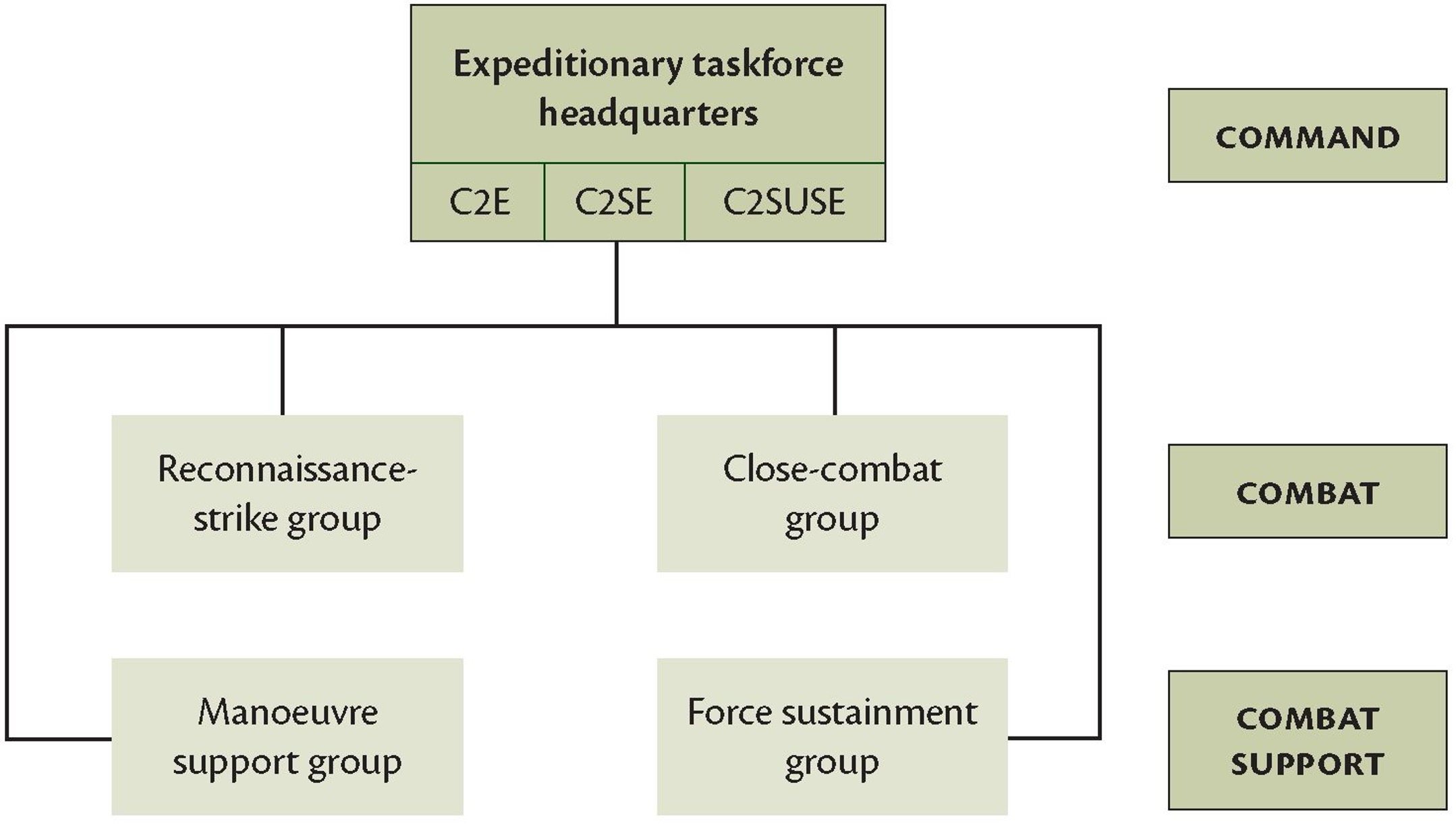

Figure 1. Organisation of the Expeditionary Task Force.

A proposed ETF would be designed in such a way that it could be employed across the spectrum of conflict in scenarios ranging from low- to mid-intensity conflict. The taskforce’s organisation would be designed to be structurally flexible, and capable of being reorganised depending on the scale, intensity and duration of any given conflict.8 In addition, the proposed taskforce would be able to operate independently or as part of a larger joint or combined force. Figure 1 depicts how such a force might be organised. The ETF is envisaged as possessing five components: a Headquarters, a Reconnaissance–Strike Group, a Close-combat Group, a Manoeuvre Support Group; and a Force Sustainment Group.

The ETF Headquarters

For the effective command and control of a future ETF, it is proposed that its headquarters consist of four elements: the commander, the command-and-control component, and command-and-control support and sustainment elements respectively. The taskforce’s command-and-control arrangement should seek the maximum integration of staff functions in order to avoid the conventional model that dominates existing staff systems. Successful integration would require only three headquarters branches: those of Operations, Plans and Intelligence.

The command-and-control support element would be responsible for the provision of operational support to the headquarters, including the provision of communications and security. The command-and-control sustainment element would, on the other hand, be responsible for such functions as transport, and miscellaneous administrative, medical and logistical requirements.

The Reconnaissance-Strike Group

The struggle for situational awareness would be a core activity of the taskforce. It would be the responsibility of a Reconnaissance–Strike Group consisting of four key elements: a ground-based, manned reconnaissance element (augmented with unmanned ground vehicles and sensors); an aerial reconnaissance element (augmented with unmanned aerial vehicles); an information operations element; and a fire support element. A reconnaissance–strike group would exploit two integral capabilities. First, a robust, timely, and accurate reconnaissance system to direct the taskforce commander to the adversary’s dispositions in the field. The second capability would be the means to support the taskforce commander’s plan through the coordination and provision of fires.

By 2020, it is likely that significant advances in reconnaissance and surveillance systems will allow a land force to achieve optimum situational awareness of the battlespace. In the future, the Reconnaissance–Strike Group will probably be capable of collecting information from a wide variety of automated assets, particularly unmanned ground and air vehicles and unattended ground sensors.

The Reconnaissance–Strike Group would not only seek out the adversary’s vulnerabilities, but it should also be organised to capitalise on superior knowledge. The cycle of collection, analysis, dissemination and target attack is likely to become compressed in the future, and the group would require an integral capability to direct and undertake a range of precision strike and fire support missions. Such capabilities would support the taskforce in both the deep and close battles.

The Reconnaissance–Strike Group’s integral ability to ‘strike’ would be based on armed reconnaissance and surveillance platforms—both manned and unmanned—as well as dedicated lethal fires, cyber and electronic attack assets. Both air and ground reconnaissance systems must, in future combat, possess the ability to conduct immediate strike operations. By integrating a range of strike capabilities within a single organisation, an ETF reconnaissance–strike group would establish a clear ‘knowledge edge’ over the adversary across the tactical, operational and strategic levels of war.

It might be important to enhance a future reconnaissance–strike group’s conduct of precision strike and fire support missions by assigning a fire support element to the group. A fire support element would provide highly responsive indirect fires in order to ensure an efficient and rapid ‘sensor-to-shooter’ linkage. The provision of a specially layered system of fire support would help to shape the battle and assist in the conduct of close combat. Such layering of ETF fire support would best be achieved through the employment of a three-tier system. The first tier of fires would be based on a medium-range, mobile system capable of firing a range of ammunition to strike at both point and area targets. The focus of first-tier fires would be to support the conduct of the close battle. The second tier of fires would concentrate on long-range precision strike and on achieving area effects. A second tier might incorporate mobile rocket-propelled systems or long-endurance unmanned aerial vehicles armed with precision munitions. The focus of the second tier of fires would be to support the deep battle. Finally, a third tier of firepower would use directed-energy weapons—lasers that may be able to achieve highly controlled, line-of-sight accuracy and so destroy high-speed targets such as aircraft, artillery shells, and missiles.

The Close-Combat Group

In the Australian Army, the infantry is the premier close-combat element. Australian Army doctrine has long upheld that the role of the infantry is to ‘seek out and close with the enemy, to kill or capture him, to seize and hold ground and repel attack by day and night, regardless of season, weather or terrain’.9 In the future, however, if the infantry are no longer required to focus on seeking out the enemy, it might be argued that the traditional concentration of infantry battalions within a legacy brigade (two to four battalions) is no longer required in 21st-century conditions.

If the proposed ETF’s reconnaissance–strike group is able to provide a robust information collection and ‘hard-soft’ kill capability, infantry will no longer be required to expend much of its effort ‘feeling’ for, or moving to contact with, the enemy. Rather, the infantry battalion can concentrate on developing a precision strike capability that responds to the targeting information provided by the Reconnaissance–Strike Group.

A close-combat group should be created in order to provide the taskforce of the future with the ability to close with and destroy an enemy in both normal and complex terrain, including urban areas. In order to ensure that this group can be ‘cued’ on to a target quickly by intelligence from information supplied by the reconnaissance–strike group, the close-combat group must be capable of undertaking rapid, mobile and highly dispersed operations. The need for dispersed operations suggests that the Close-combat Group should consist of several sub-units, each possessing a capability to close with a target. As a consequence, it is argued in this article that the support company elements of an existing infantry battalion be embedded within the rifle companies. In order to be able to respond in at least two dispersed locations concurrently while maintaining a reserve, the close-combat group should possess four companies. Each close-combat company would consist of light infantry with integral short-range direct and indirect fire support, and close reconnaissance and communications assets.

In addition, the Close-combat Group should also possess a light mechanised subunit that would be capable of mounting at least two of the close-combat sub-units in addition to providing direct fire support. This light mechanised sub-unit of the Close-combat Group could be equipped with vehicles capable of being transported by C130 Hercules aircraft and by heavy rotary-wing aircraft. Such vehicles should also be capable of traversing the various types of terrain found in both Australia and South-East Asia during the dry and wet seasons. In this way, the ETF would be capable of conducting air-mechanised operations.10

The Manoeuvre Support Group

A future taskforce must be able to acquire knowledge of the enemy and then shape its physical environment. It is in this realm that manoeuvre support becomes important for the provision of such capabilities as combat engineers, and nuclear–biological–chemical response elements. On the future battlespace, a manoeuvre support group would be formed in order to provide combat support functions in the modern battlespace. Such support would enhance the mobility and survivability of the taskforce.

A key role for the Manoeuvre Support Group would be Organic Real-time Battlefield Shaping (ORBS), employing ‘tactical deception by means of visual, acoustic and other sensory signals (tactile, smell) to disrupt an opponent’s situation assessment process, and to modify his behavior’.11 Essentially, this type of shaping involves the application of advanced ‘special effects’ to the battlespace. This ‘special effects’ approach aims to deny manoeuvre; and to introduce uncertainty, confusion, delay or diversion, causing the enemy to make a rational but wrong decision that may prevent a direct firefight. Through the employment of in-place and remote-response sensors, mobile robots and various other obstacles, the manoeuvre support group would employ ORBS in order to produce a superior effect to that generated by traditional minefields and fortifications.

A manoeuvre support group would directly assist the taskforce’s combat elements (the reconnaissance–strike group and the close-combat group) and provide a degree of support in general operations. The direct assistance supplied by the manoeuvre support group would consist primarily of combat engineers. The group’s more general support to the ETF might involve an operations support element, providing capabilities that support generic operations such as chemical, biological, radiological responses (CBRR); ORBS; and military police. The CBRR element would be responsible for nuclear, biological and chemical reconnaissance; decontamination operations; and explosive ordnance disposal. A military police contingent would be needed to supervise efficient battlespace movement. Finally, another component that would be required for general operations would be an engineer support element.

The Force Sustainment Group

In future operations, the need for combat service support is likely to remain a critical military requirement. Within the proposed ETF, both unit (first-line) and formation-level (second-line) combat service support will be required for self-sufficiency, necessitating the creation of a force sustainment group. The latter should be organised to enable rapid capability to be generated across extended lines of communications. Both first-line and second-line support require integral services such as health, technical repair facilities, and collection of stores and equipment.

In the light of the expeditionary focus of the proposed new land force, a Force Sustainment Group would require additional capabilities not held in current brigade logistic organisations. Accordingly, extra personnel and equipment will be required to conduct port operations and/or logistics-over-the-shore (LOTS) operations.

Any future force sustainment group should be composed of four elements: transportation support, health services support, supply support and field repair. The basic principles of logistical planning—simplicity, cooperation, economy of effort, foresight, flexibility and security—are almost certain to remain as applicable to an ETF in 2020 as they are to the current Army.12

The ADF and the Expeditionary Task Force

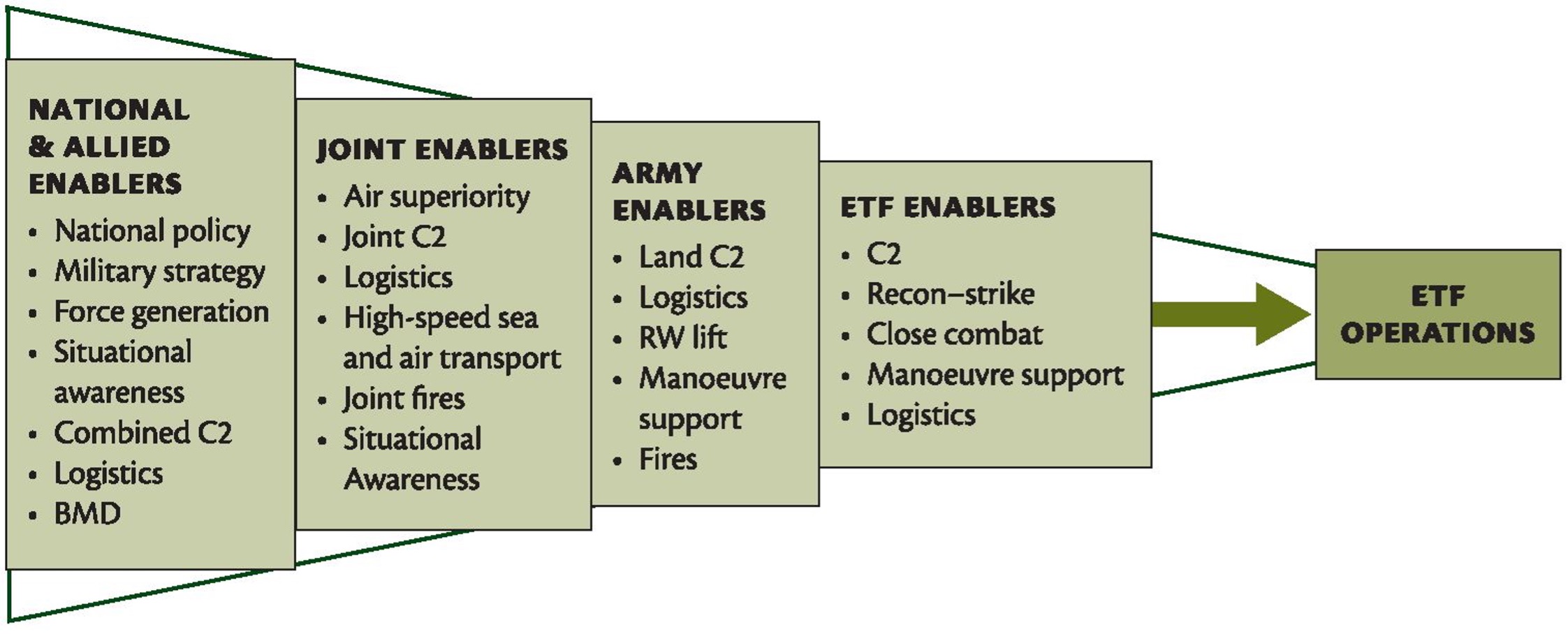

The proposed taskforce is not intended to operate by itself, without reference to other elements of the ADF. On the contrary, the ETF would form part of a joint (or combined) force. Any future taskforce organisation would have to demonstrate its ability to respond to Australia’s emerging 21st-century strategic needs. As a result, situational awareness that is derived from national and allied information sources would be essential, as would the maintenance of a joint command-and-control support infrastructure. The ETF would also need to be able to rely on a layered joint-fires capability as well as air superiority over areas of operation and lines of communications. In addition, the ability to move troops and supplies by sea and air to an area of operations rapidly and without interference would be crucial to the success of the ETF. Tactical mobility using troop-lift helicopters and armoured personnel carriers would also need to be ensured in any offshore mission. Finally, there would have to be adequate logistical support in order to sustain ETF operations in Australia’s littoral environment. The levels of support that may be required for ETF operations are depicted in Figure 2.

Conclusion

The only certainty we can expect in future conflict is uncertainty. Napoleon once said that ‘an army ought only to have one line of operation. This should be preserved with care.’13 Unfortunately, land warfare is no longer linear, and the armies of the future must be capable of undertaking a wide range of concurrent operations in austere conditions and in potentially hostile environments. In order to meet new conditions of complex warfighting, the Australian Army must consider the future of its combat organisation that remains 20th century in character and ethos.

Figure 2. Generation of ETF Combat Power

The force model of an ETF outlined in this article acknowledges that, despite the high technology of information-age conflict, the focus of warfare remains the clash of human wills. Our challenge is not simply the sophisticated cyber-warrior, but also the road warrior who may be a tribal warlord equipped with a cell phone and modern missile technology. As a result, the flexibility, mobility, firepower, and networked communications of a future land force will be the keys to Australian military success in the future.

The model of a future Australian land force described in this essay seeks to address the impending crisis that all Western military organisations will face if unreformed industrial-age structures are used to meet the multidimensional demands of future conflict. As Australian society changes under the impact of information-age networks, decentralised work practices and the increasing emphasis on developing intellectual capital, so too must the Australian Army also transform. The threats that the Army will confront in 2020 will be unlike those of the late 20th century in that they will be more complex, diffuse and interconnected, and may cross borders and penetrate societies. Meeting and overcoming such challenges demands the right mix of personnel, reformed organisation, new equipment, innovative doctrine, and imaginative training. The Army cannot wait passively to react to new challengers. Instead, we must seek to anticipate the future and shape our responses to meet emerging realities.

Endnotes

1 Lieutenant General Peter Leahy, ‘Future Wars, Futuristic Soldiers’, a speech to the Land Warfare Conference, Convention Centre, Brisbane, 23 October 2002.

2 Carl von Clausewitz, On War, Everyman’s Library, London, 1993, p. 83.

3 Admiral Arthur Cebrowski, a speech given to the Center for Naval Analyses, Virginia, 20 November 2002.

4 Kenneth McKenzie, The Revenge of the Melians: Asymmetric Threats and the QDR, McNair Paper 62, National Defense University, Washington, D.C., 2000, pp. 65–80.

5 Land Warfare Doctrine 1, The Fundamentals of Land Warfare, Doctrine Group, Land Warfare Development Centre, 2002, pp. 63–73.

6 Department of Defence, Force 2020, Public Affairs and Corporate Communication, Canberra, June 2002.

7 William Lind, ‘The Changing Face of War: Into the Fourth Generation’, United States Marine Corps Gazette, November 2001, pp. 65–6.

8 For a detailed explanation of the categorisation of conflict in the Australian context, see The Fundamentals of Land Warfare, p. 34.

9 See Australian Army, Manual of Land Warfare 2.1.1, The Infantry Battalion, Department of Defence, Canberra, 1983, p. 1–1.

10 For a review of the concept of air mechanisation, see David Grange, Richard Liebert and Chuck Jarnot, ‘Air Mechanization’, Military Review, July–August 2001.

11 Kathy Harger, John Bosma, Wayne Martin, James Richardson and Rosemary Seykowski, Antipersonnel Landmine Alternatives: Organic Real-time Battlefield Shaping, Potomac Institute for Policy Studies, Arlington, VA, 1999, p. 4.

12 The Australian doctrinal publication Training Information Bulletin, Number 70, Brigade Administrative Support Battalion, 1995, has been consulted extensively in the preparation of this section of the paper.

13 David Chandler, The Military Maxims of Napoleon, Da Capo Press, Cambridge, MA, 1995, p. 59.