The most powerful tool we have in succeeding in this era of strategic competition is not the weapons we have, nor is it technology. It is the people …

Chief of Army LTGEN Simon Stuart LANPAC 2024

Introduction

One distinguishing element of a profession that sets it apart from other jobs is a commitment to ethical and moral conduct. The ‘profession of arms’ is like medicine, law and ministry—professionals who share a commitment to practising a role within the ethical bounds of agreed ethical frameworks.[1]

The Chief of Army has appealed for an assessment of the state of the Army profession and suggests the three pillars of the profession of arms are ‘jurisdiction’, the unique service Army provides to society; ‘expertise’ in a distinct professional body of knowledge; and capacity to ‘self-regulate’. All three pillars relate to ethics, but self-regulation is especially important in guarding against war’s corrupting influence, calling for ethical foundations that ‘must be at once uncompromising and uncompromised’.[2]

One of the combat behaviours required of an Australian Army soldier is ethical decision-making, and it underpins all other behaviours.[3] Since 2002, the Centre for Defence Leadership and Ethics (CDLE) has emphasised the importance of ethical leadership in a military context. CDLE led the compilation of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) ‘Philosophical Doctrine on Leadership, Character and Ethics’.[4] Relatedly, it is currently developing training continua for integrating character-based leadership at each stage of the military career for joint professional military education (JPME) beyond induction training.[5] Since 2019, the Centre for Australian Army Leadership has been delivering the Australian Army Leadership Program across Army’s promotion courses, including integrating ethics lessons in every leadership course. Army Special Operations Command has developed ‘ethical armouring’ to equip its members to operate ethically at all times and to return from service both physically and morally whole.[6] These are freshly contextualised initiatives to remind present and future soldiers what past Aussie diggers have long esteemed—a proud tradition of being and behaving upright and ethically. Ethical behaviour is about doing good things (good soldiering) undergirded by strength of moral character—being a good person.

Character is that moral construct that ‘relates to how we use moral sense to distinguish good from evil, right from wrong, just from unjust, and virtue from vice’.[7] The whole purpose of virtue ethics is to inculcate good character in people so that they will be good people who make good decisions.[8] A revival in virtue ethics and virtuous practices is important in military ethics education because it underlines the Aristotelian foundations of character that guides behaviour rather than relying on rules when we cannot foresee every situation.[9] Specifically, we cannot teach soldiers drill-based responses for every dilemma they may face, because we cannot imagine all the complex issues future warfare will present.

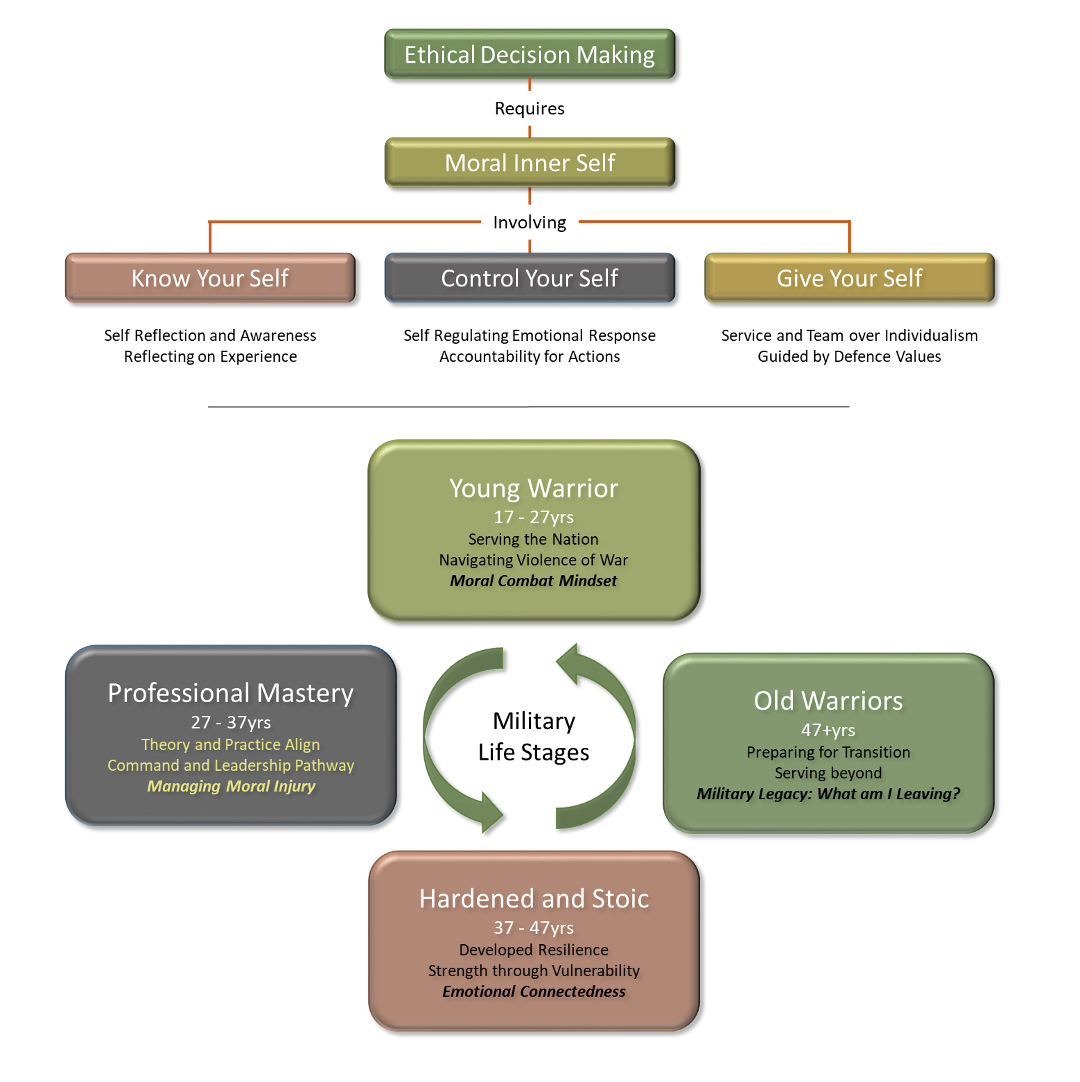

To help posture Army for future land warfare challenges, soldiers need a moral framework. This is part of the enduring nature of war despite changes to strategic imperatives and adaptations in methods of warfare.[10] It is nothing new. Acknowledging this enduring characteristic, this article is an invitation to refocus character training around the development of a clear moral inner self, and to offer generation-specific training across a soldier’s career life stages.

Character training and ethics education occurs intentionally in ab initio training environments. These include the Army Recruit Training Centre—Kapooka, the Royal Military College—Duntroon, and sometimes initial employment training (IET) conducted at various military bases throughout Australia. In those contexts, however, it can be difficult for learners to absorb character and ethics lessons alongside everything else. Once a soldier is posted to a unit the presumptive need for good character prevails, but ongoing formal character development is at the discretion of command and, while touched on during promotion courses, can be otherwise challenging to timetable. At the practical level, character development is every leader’s responsibility every day—to set a moral example and be attentive to opportunities to develop character in team members.

It is the remit of a chaplain to support command with monitoring, coaching and resourcing character development in formal and informal contexts.[11] This is part of the chaplain’s role description and draws on their expertise in cultivating values and beliefs. Where then can chaplains complement and resource character development initiatives, and what is needed at different life stages of soldiers through their careers? This article offers chaplains—as well as soldiers and commanders—a philosophical and pedagogical framework through which to facilitate learning about a soldier’s moral inner self. It also proposes a generational understanding of soldiers across their career and suggests a key lesson for each stage.

Towards a Moral Inner Self

The development of the inner self (the so-called ‘invisible underside’[12]) is critical for guiding moral and ethical decision-making. Soldiers need fit bodies, healthy minds and sustaining relationships, but also the grounding of purpose and meaning that comes from the spiritual dimension of the inner self. This article argues for the development of this equally important grounding of purpose. Chaplains bring a distinctive contribution to supporting the spiritual dimension, as well as holistic pastoral care across the bio-psycho-social-spiritual spheres.[13] Joint Health Command and the Defence Mental Health and Wellbeing Branch have adopted a bio-psycho-social-spiritual support posture for wellbeing, incorporating meaning and spirituality as an important wellbeing factor.[14] The moral inner self addresses the belief systems that determine the values that shape behaviour at work, at home and in the community.

To set the framework for considering opportunities for formal and informal character development within Army, this article draws upon the characteristics and behaviours of human life-span development theory. This theoretical basis helps explain how humans learn, mature and adapt from infancy to adulthood to elderly phases of life, and how this interacts with resilience.[15] The consistent theme through each of these stages is the formation of the moral inner self, guided by three statements that underpin personal responsibility and accountability:

- Know your self

- Control your self

- Give of your self.

This is known as the LEO ‘K-C-G’ character development model, originating from the life and ministry of Chaplain Lionel Edward Orreal CSM (Ret.), commonly known as ‘Leo’. It serves as a tribute to his boundless energy, passion and faithfulness to ‘serve the soldier’. It is meaningful for us as chaplains, especially some of us who know him, to use Orreal’s framework. Yet more significantly, the K-C-G framework complements other models of character development while emphasising the importance of giving attention to one’s self for the end purpose of service.

Know Your Self

The Socratic dictum ‘The unexamined life is not worth living’ reminds us that the pursuit of knowing yourself has characterised the desire for meaning, purpose and identity for thousands of years. Knowing yourself requires self-reflection and self-awareness about one’s personality and temperament, strengths and weaknesses, assumptions and blind spots, worldview and cultural assumptions.

The person with poor self-awareness is usually unaware of why they behave how they do and how their behaviour affects others. They may be oblivious to the masks they wear, creating a duplicity that lacks integrity. Inability to take responsibility for one’s thoughts and actions limits the development of character and leadership. Honest self-awareness challenges known and unknown fears, insecurities and masks, and fosters responsibility for thoughts and actions as a basis for sound ethical and moral decision-making.

John Dewey commented: ‘We do not learn from experience, we learn from reflecting on experience.’[16] To ‘know yourself and seek improvement’ is the foremost of the ADF leadership behaviours.[17] But self-awareness is not an end in itself. To know oneself is a prerequisite for controlling oneself, the purpose of which is to give of oneself in service to others.

Control Your Self

Knowing oneself is about being self-aware and self-reflective, while also being self-regulating and self-controlling. This takes particular resilience in the context of challenge and adversity. Self-regulating emotional response to adversity and overcoming intense fear demonstrates resilience of the inner self. It provides the ability to recover quickly from setbacks and stressful situations and to adapt to new circumstances. It helps transform us beyond self-centredness and self-preservation. It also helps model and lead others in these directions. By example, leaders motivate and influence others to push themselves beyond their perceived limits and achieve far more than they had imagined they were capable of. They also set the ethical tone of their units.

ADF mandatory training includes instruction in workplace behaviour, the essence of which is controlling yourself and showing respect to colleagues. Values-based behaviour requires everyone to accept personal responsibility and accountability for their actions, and to think about the consequences of their behaviours and actions for themselves, for others, and for Defence more broadly. When members come to the organisation with dysfunctional backgrounds or rigid mindsets, they need leaders to be the ‘moral brake’ who can align values and behaviour in appropriate directions. Ultimately, soldiers do best to exercise this self-control themselves.

To control your self is not a process of disassociating from one’s emotions. Emotions play a vital role in the process of self-reflection, providing a window into the soul. To control oneself requires a person to recognise and identify the emotions they are experiencing—and sometimes to ‘feel the fear and do it anyway’.

Give of Your Self

Being self-aware of and controlling yourself are not ends in themselves. They are also the basis for being ready and able to give yourself in service to others. The end goal of self-awareness and self-control is service, the first Defence value: ‘the selflessness of character to place the security and interests of our nation and its people ahead of my own’.[18] This selflessness of character represents the highest of ideals, challenging the nature of individualism and self-centeredness.

Giving of yourself in service has natural synergy with—and is guided by—other Defence values. Service takes courage—‘the strength of character to say and do the right thing, always, especially in the face of adversity’. Without physical courage, it is difficult to lay our lives on the line. Without the conviction of moral courage, it is difficult to lay our reputation on the line and consistently say and do the right thing.

Giving priority to others also comes from respect—‘the humility of character to value others and treat them with dignity’. Serving with respect is learned through interpersonal relationships, in teams with people different to us, and in humility as we recognise the dignity of civilians and of enemy forces.

Transcending self-interest and fighting for the interests of the nation and its people is also fuelled by integrity—‘the consistency of character to align one’s thoughts, words and actions to do what is right’. When we know in our inner self what is right, we express that in right actions and truth in speech.

Finally, giving of yourself is framed by excellence—‘the willingness of character to strive each day to be the best I can be’. Striving to transcend self-interest is a continuous process—for every career stage. Relational dynamics within military teams allow character shortfalls to surface. With skills of self-reflection, we can work through character and relational shortfalls. This is an exercise in excellence—being the best and better version of ourselves in the interest of better serving the people of Australia.

The LEO K-C-G framework of knowing, controlling and giving of yourself allows for individual lesson development and delivery. It is a simple development trajectory for people to reflect upon their values, beliefs and behaviours, and to challenge their assumptions, biases and blind spots. It can guide formal or informal lessons for teams. It also provides a useful guide for counselling, providing a simple structure and language to challenge and improve behaviour and thinking. Moreover, it can be tailored and applied to members at different stages of the military life cycle.

Military Life Stages

Moral framing means different things for soldiers at different stages in their careers. We propose a model of four stages of military service, beginning at age 17 (see Tables 1 and 2). Each stage, defined by an additional decade of service life, builds on previous stages of development. The first, the young warrior, represents the initial stage of enlistment and service that shapes the military and combat mindset. The second, professional mastery, describes those who embrace the military life as a calling and a career. The third, hardened and stoic, represents the more senior levels of service. Lastly, old warrior describes those who have committed the greater part of their life to military service.

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| Stage 1 | Young warrior (17–27 years) |

| Stage 2 | Professional mastery (27–37 years) |

| Stage 3 | Hardened and stoic (37–47 years) |

| Stage 4 | Old warrior (47 plus years) |

Each stage includes general age brackets, though sometimes people enter a stage at a different age.[20]

The ‘four military life stages’ model is reflective of other age-based typologies such as Piaget’s cognitive development theory, Erikson’s psychosocial development stages, Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory, Kohlberg’s moral development stages and Fowler’s faith stages.[21] Further research may explore connections between these theories and military life stages. For the purpose of this discussion, the purpose of the stage and age guidelines is to invite commanders, chaplains and members to think about where individuals are in their military career development and what lessons are needed at different stages. The intention is to tailor character training for different career stages—allowing for flexibility to adjust lesson plans, pastoral counselling and training activities to suit the respective audiences, utilising whatever holistic learning spaces are available to enhance character and ethics in the context of the JPME continuum.[22]

To cultivate a moral inner self in soldiers, we propose one key lesson for each stage. These lessons have relevance across a soldier’s career, but we suggest they deserve particular attention for soldiers at particular stages.

Stage 1—The Young Warrior (17–27)

The term warrior is a contentious description of soldiers within the ADF. Some suggest the ADF does not widely identify with a warrior culture. The negative perception of ‘warrior’ is more commonly attributed to American culture and has been popularised in the Australian Army after operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. Australian veterans from earlier conflicts have not widely described themselves as warriors, though they recognised that being a soldier was about fighting and (if required) killing. A ‘warrior culture’ of ‘warrior heroes’ was identified in the Afghanistan Inquiry as a factor that led to ADF personnel being implicated in war crimes.[23] Deane-Peter Baker suggests ‘guardian’ is a better term than warrior.[24] Others use ‘combatant’ or ‘war-fighter’. Warrior as a description of the Australian soldier is not widely appealing to the ADF or the Australian public and is not used by Defence Force Recruiting. Thus there are a number of reasons to be wary of promoting the use of the term.

However, we believe ‘young warrior’ is a helpful typological description of the first stage in the service of an Australian Army soldier (or Navy sailor or Air Force aviator). It is relevant to the need at this stage to develop a moral combat mindset. We note that Deputy Chief of Army Major General Chris Smith is urging Army to reclaim and achieve a modern warrior culture.[25]

Warrior culture … needs to be a culture that wins battles, and by extension wins wars. It must sustain morale and a fighting spirit. It needs to imbue soldiers with the ability to kill. It must be a noble culture with an element of restraint, mirroring the expectations of the society that sends us to protect it. It needs a strong sense of loyalty, loyalty to the government and the cause for which we fight for. It must include an obedience to the lawful orders of the chain of command complimented [sic] by a strong sense of discipline.[26]

Deputy Chief of Army is referring to the ethos of the moral combat mindset that we believe is crucial for ‘young warriors’ to adopt and embody. Warrior as a term is gender neutral and generic, and inclusive of all arms of military service. Moreover, warrior suggests a role that ideally is about serving the community, engaging in war for the sake of defence of others—that is, a moral focus.[27] Thus, in the tradition of typology, ‘young warrior’ is a good depiction of the first stage of the military persona. We are not espousing it as a label for Australian soldiers (or sailors or aviators). But it is descriptive of this first phase of military service. Ages 17 to 27 represents the formative stage of military service and the shaping of the military identity. In the JPME continuum this stage incorporates learning level 1 (induction) and evolves into level 2 (intermediate).[28] It is a period when individuality, independence and identity are central to self-worth and self-image. The young warrior is usually highly motivated, competitive and impressionable, determined to prove their worth and find their place in a community that measures itself by high standards.

Prior to enlisting, young warriors commonly have limited life experience, with an underdeveloped interest in or aptitude for developing the inner self. To overcome the self-serving bias that has limited understanding of personal strengths and weakness, the primary need during the young warrior stage is to develop skills and practices of self-awareness and self-regulation—to know and control yourself.

An ambitious young person is fabled to have asked a master:

‘I want to be your student, your best student. How long must I study?’

‘Ten years.’

‘But ten years is too long. What if I study twice as hard as all your other students?’

‘Then it will take twenty years.’

Young warriors cannot shortcut the development of self-awareness and self-regulation.

Lesson preparation for young warriors in the first stage of service life must look at the nature of the self and the need to develop self-reflective skills that allow for character and leadership growth (knowing yourself in order to control and give of yourself). One key lesson throughout this stage—from recruit training, through IET and development as a junior leader—is to cultivate the military and combat mindset.[29]

A Moral Combat Mindset

Young warriors need to be formed and encultured in a certain mindset—a military and combat mindset—and this needs to be intrinsically moral. The primary purpose of developing the combat mindset is to condition young warriors to face the rigours of war and death. Military service requires the development of warfighting skills, knowledge, attitudes and behaviours to seek out and engage with an enemy, kill them, and be prepared to die oneself. This is the ‘contract of unlimited liability’ that is central to the idea of the professional soldier.[30] There is no sugar-coating the brutal nature of war fighting.

Infantry Officers Caligari and Lewis describe the development of mindset before skillset:

The Combat Mindset is a state of mind that prepares soldiers to kill the enemy, survive, and then continue the fight. This state of mind offers the optimal paradigm for training Australian soldiers, and promotes the development of resilience and intuitive behaviours to perform in battle …

The Combat Mindset’s foundation identifies the combatant, not his tools, as the weapon—a system that operates cohesively to kill the enemy. The Combat Mindset is the defining philosophy of the professional soldier; it is the difference between a true soldier and someone who simply has weapons qualifications and equipment …

A key outcome in the adoption of Combat Mindset training is the ‘pre-combat veteran’—a soldier who has the skills, deep understanding of warfare, and maturity of a combat veteran, but is yet to fire a shot in battle.[31]

Caligari provides valuable insight into the formation of the young warrior’s mindset and identity. The language characterises the mindset—‘a state of mind that prepares soldiers to kill the enemy, survive, and then continue the fight’. Within the profession of arms, the combat mindset makes sense, but describing a person as a weapon system that operates cohesively to kill other humans highlights potential moral dissonance in the development of the young warrior, in particular the effect on an adolescent brain.

The ADF’s publication Chaplaincy in War (2024) recognises that military personnel have a unique way of looking at life as they train and prepare for war. The potential violence brings a brutal reality of fear, ambiguity and confusion, different from the reality of normal civilian jobs.[32] Survivability and resilience depends on whether soldiers adopt a combat mindset.[33] Army has training in combat behaviours to drill to enhance survivability and effectiveness. These include combat shooting, Army combatives, tactical combat casualty care, combat physical conditioning, behaviour of combat communication (a recent addition)[34] and foundational training in ethical decision-making. Ethical decision-making synergises with the other five behaviours—positioning soldiers not just to win battles but to help win the war by winning ‘hearts and minds’. Importantly, training soldiers in ethical decision-making positions the ADF to uphold its national reputation by diminishing the risk of war crimes being committed by its members. We are also concerned not just with physical survivability but with bringing soldiers home with their souls intact. This requires ethical decisions, an ethical culture, and a moral combat mindset building on a moral inner self.

The combat mindset has a powerful effect upon the adolescent brain and the bio-psycho-social-spiritual growth of young adulthood. Jünger in Tribe emphasises the military’s universal and historical practice of disproportionately drawing recruits from troubled families.[35] The development of self-awareness and self-regulation is difficult for those who have suffered trauma during early developmental stages of life. Such individuals are more likely to struggle to emotionally process and communicate their feelings, making it difficult to turn a combat mindset on and off or differentiate between normal and abnormal behaviour.

How do we develop not just a combat mindset but a moral combat mindset in young warriors? Firstly, we need to discuss the moral component of fighting power. Chaplains teach about beliefs and values at Kapooka, inviting recruits to reflect on what worldview and belief system they draw on. The same type of individual reflection is also needed in IET and unit contexts. Foundations of Australian Military Doctrine underlines that soldiers need physical, mental and spiritual preparation and training to condition their minds and bodies for war:

War is by nature brutal and tough. In this environment, the ADF must understand and enforce the rule of law so that they can rise above the chaos and uncertainty and achieve the missions and objectives set by Government. The ADF’s people need to be spiritually, mentally and physically tough enough to conduct war.

Spiritual, mental and physical toughness are not innate qualities gained at birth; they must be developed. This requires deliberate and demanding preparation through training, and through the Service and joint professional military education system.[36]

Fighting power derives from the integration of these three components: the intellectual component provides knowledge to fight, the physical component provides means to fight, and the moral component provides will to fight.[37] Their synergy creates warfighting power in the military and combat mindset. The intellectual and moral components also combine to help with ethical decision-making, including dilemmas of balancing achieving the mission, protecting one’s mates (or—for commanders—the soldiers one leads), and protecting non-combatants.[38]

Secondly, a moral combat mindset is best modelled and taught by senior soldiers and officers, but also supported by chaplains. Credibility and authority come from experience. In every military environment, there are leaders and mentors who have the respect and admiration of the young warrior. They are the people the chaplain best utilises to communicate to young warriors. Their example and experience impart inspiration and motivation for change. Anecdotally, we have observed that the co-teaching of combat mindset by chaplains and senior soldiers offers several benefits. The senior non-commissioned officer (NCO) can share from their perspective and experience, while the chaplain facilitates, presents ethical tools and is available for individual follow-up. Junior NCOs also have an important role to play—moral framing is unlikely to be adopted if a soldier’s leader does not agree with it and embodies this dissonance in their interactions with troops. NCOs and senior officers are often the ‘more knowledgeable other’, to use Vygotsky’s sociocultural term,[39] who helps young warriors cultivate a moral combat mindset.

Thirdly, a moral combat mindset can be developed through integrated field-based training, not just classroom education. Through hard training, the discipline of controlled aggression allows for the development of self-regulation, shaping the behaviour of the individual and the team. Many young warriors are still adolescents in terms of development, prone to impulsiveness in decision-making without considering consequences.[40] As we train young warriors in the military and combat mindset, it is imperative to develop the moral inner self in order to prepare the next generations of members for ‘good soldiering’ and the highest standards of ethical decision-making and moral behaviours—and this is best done using scenarios in field-based training.

Whatever trade or specialty they pursue as soldiers, young warriors need a moral military and combat mindset. They need to be able to integrate this mindset with their sense of moral inner self, while also maintaining separation in order to sustain a healthy life outside of the ADF, including being ready to transition when they leave the organisation.

The Royal Commission into Defence and Veteran Suicide identified that leaving the ADF involuntarily was a serious risk factor for suicidality.[41] This may especially apply to young members, and we note that a number of our personnel do not serve beyond four years and some serve for far less.

Stage 1 lessons will help young warriors understand their military service and identity within the wider responsibilities of life. But stage 1 lessons also help soldiers develop their moral inner self to be positioned for cultivating professional mastery.

Stage 2—Professional Mastery (27–37)

The second stage of the military demographic represents consolidative years of service, defined as professional mastery, when theory and practice align. In the JPME continuum, this stage incorporates the completion of level 2 (intermediate) and moving into level 3 (joint operational).[42] Achievement of professional mastery at this level demands the highest degree of moral character and leadership in conjunction with trade competency. Life-stage theorists, beginning with Erikson, refer to ‘ego strength’ as a middle adult stage of productivity, creativity and procreativity.[43] For soldiers, professional mastery is the goal that young warriors aspire to grow into, the measure of military success. Through professional mastery, the military identity submits its autonomy to a calling of selfless service. For most commissioned officers, professional mastery defines the pathway for command and leadership responsibilities. Positions of senior corporal, sergeant and warrant officer embrace the responsibilities of military custodianship.

Caligari emphasised the combat mindset as the defining philosophy of the professional soldier. The transition from young warrior to professional mastery requires self-reflection and forward projection, asking ‘What do I need to do to become the person I want to be?’. The convergence of knowledge and experience creates a synergy of confidence, authority and responsibility.

Yet as soldiers develop as young warriors and as they develop professional mastery, they can also become desensitised to the emotional consequences of military service. This can occur due to the loss of mates killed in training or operations; to missed opportunities (such as being overlooked for deployments, promotions and courses); or to relationship failures. Such factors all take a toll within the moral conscience. Operational service and combat-related experiences can suppress the moral conscience, hardening the heart, reducing empathy and compassion. This can cause distance in friendships and family relationships, and a hardening rather than development of the moral inner self. An important key concept for soldiers to understand, coinciding with the development of professional mastery, is moral injury.

Moral Injury

Moral injury is a complex term to define,[44] although pivotal to understanding the workings of the inner self for knowing and regulating oneself, which is particularly important given the stress of moral dilemmas upon one’s mental health and wellbeing. Indeed, moral injury can be classified within the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR) under the symptom cluster of ‘moral, religious and spiritual problems’—namely ‘experiences that disrupt one’s understanding of right and wrong, or sense of goodness of oneself, others or institutions’.[45] The ADF specifically defines moral injury thus:

Moral injury is a trauma related syndrome caused by the physical, psychological, social and spiritual impact of grievous moral transgressions, or violations, of an individual's deeply-held moral beliefs and/or ethical standards due to: (i) an individual perpetrating, failing to prevent, bearing witness to, or learning about inhumane acts which result in the pain, suffering or death of others, and which fundamentally challenges the moral integrity of an individual, organisation or community, and/or (ii) the subsequent experience and feelings of utter betrayal of what is right caused by trusted individuals who hold legitimate authority.[46]

Fundamentally, moral injury occurs when an external experience transgresses or violates a person’s conscience, their sense of right and wrong, undermining their belief system—creating a conflict within the inner self. Pastoral narrative disclosure[47] is the ADF model which can be utilised by chaplains (military[48] and civilian[49]) to help address and rehabilitate personnel from moral injury.[50] What we discuss here is how an understanding of moral injury can coincide with and support professional mastery, and how professional mastery can respond to potentially morally injurious encounters.

In order to apply a moral combat mindset, young warriors and more experienced soldiers need to learn when and how it is right to apply lethal force. A dilemma of military service and the combat mindset is that Army trains soldiers to kill—normally an act against a healthy moral conscience. To kill a human being is usually an immoral act, yet it is legally justified in the military under necessary rules of engagement. Learning how to process sanctioned killing and associated consequences of warfighting is critical if the impact of moral injury is to be minimised. Where the rationale for killing is clearly justified (as when an opposing soldier is a threat to them and their country), soldiers understand that this is the nature of their role and do not usually feel guilty or suffer moral injury. However, other behaviours in war—acting outside the ethical bounds of just war—are always wrong. For example, when soldiers perpetrate unethical acts, a guilt response is appropriate—and accounting for and healing from the moral injury is necessary. This is all part of the journey of professional mastery.

One of the contributions of Ukrainian military chaplains is helping their soldiers through character training, mentoring and rituals to maintain morality and ethics during a prolonged war on their own soil. The desired effect is to preserve the individual humanity of military personnel and to help them avoid reckless behaviours, war crimes and moral injury.[51]

Professional mastery represents the epitome or culmination of the young warrior’s skills and strengths. Coinciding with the development of the skills and leadership of professional mastery, it is critical for soldiers to develop their moral inner self in ways that help them understand, navigate, avoid or, if necessary, heal from morally injurious events. This is for the sake of the soldier’s own soul and mental health, and those of their families, friends and colleagues.

Stage 3—Hardened and Stoic (37–47)

The term ‘hardened and stoic’ is applied to the more senior military personnel and describes a distinct type of military demographic. Greater responsibility and greater accountability characterise this demographic, often requiring a prioritisation of ADF needs above personal needs. This stage requires highly developed leadership and technical skills and corresponds with JPME continuum learning level 3 (joint operational) and/or level 4 (integrated).[52] This article focuses more on the relationship needs at this military life stage.

Having given the greater part of their life to service in uniform, this demographic is difficult to influence. Varying levels of moral injury and mental health related issues sometimes characterise the inner self, compounded by a military culture that ensures professional mastery masks outward signs of perceived weakness. Members who become hardened and stoic may rarely seek external help, enduring hardship and challenges as part of their professional duty.

It is sometimes difficult to talk about feelings with the hardened and stoic, especially when conditioned by a combat mindset. Nevertheless, older military people may be open to reflecting on and talking about their feelings, especially after relationship struggles or highly emotional or traumatic experiences. Understanding feelings is essential to developing the inner self, which reinforces why the development of personal character and leadership is critical. Emotions give a person a sense of being alive; they move people. Without feelings, people lose interest in things, in life itself. The greater the inability to feel and emotionally engage, the greater the risk of moral dissonance, compounded by moral injury. A person can become detached or disassociated from the things that give meaning and purpose, often appearing insensitive to the needs of others. An unattributable popular saying is ‘A slab of concrete doesn’t have to worry about weeds—but it will never be a garden’, which suggests to us the need for vulnerability if we want to grow and be creative.

Even if not interested in ‘growth and creativity’, members still need to learn to be ethical because of negative consequences for them and others if they are not. Yet the emphasis on self-discipline and self-control that is required to be combat ready has an effect on the inner self, particularly emotions. If a person is to lead by example, and be capable of demonstrating Defence values and behaviours, they must have the capacity for empathy and compassion—this is part of their moral responsibility as a leader.

Stoicism provides a philosophical code well suited to military life. Stoicism teaches that a person cannot control the circumstances that happen to them; they can only control their response. This thinking is repeated in the classic teaching of Victor Frankl.[53] If not a necessary philosophy of a soldier at any stage of service, some teachings of stoicism provide helpful coping mechanisms. For example, Jim Stockdale modelled and popularised stoicism from what he learned in maintaining morale as a prisoner of war in Vietnam.[54]

Ethicist Nancy Sherman in Stoic Warriors explores the relationship of stoicism to US military culture, seeking to understand ‘the attractions and dangers of austere self-control and discipline’.[55] She points out that there is a cost to being stoic, describing stoicism as a blessing and a curse for those in the military: ‘A blessing in that it girds them for facing the horrors of war, a curse in that it cannot deliver and that leads to the undoing of the mind.’[56] Sherman acknowledges the strengths and qualities of stoicism that describe the military persona, while cautioning her readers to be ‘critical and wary of the stoic tendency to both over-idealise human strengths and minimise human vulnerability’.[57] This underside of stoicism—the tendency to minimise vulnerability—suggests a need for soldiers at this military life-stage to develop this quality. A primary need for this ‘hardened and stoic’ period of service life is emotional connectedness.

For members who are not ‘hardened’ by service, this is still a stage of emotional connections with significant family and friends. Many members by this stage of their career and life have formed significant loving relationships and many have begun families. The experience of partnering and/or parenthood fosters wisdom and empathy and opportunity for practising emotional connectedness. For healthy relationships, knowing, controlling and giving of yourself continues to be important.

Emotional Connectedness

Emotional connectedness begins with the self-awareness and emotional intelligence as to how life and military service affects emotions. Young warriors learn to value service for others and develop self-control as a survival instinct. To survive and thrive long term, they also need to care for themselves. We all need emotionally safe environments where we can be ourselves and not feel threatened or embarrassed. Mates in the ADF can offer this but at all stages we also need friendships and family relationships outside the organisation.

The longer a person serves without developing their inner self, the harder it is to reconcile the stoic attitude of military professionalism with the emotional intimacy needed to develop interdependency with significant others. There is much about the combat mindset that potentially clashes with family systems and the nuances of social mastery. Although soldiers may be motivated by selfless service, from the perspective of family and social life, military service can appear inherently selfish or self-serving. Professional mastery can demand continuous time away from family and friends. The ethos of sacrifice demands that the military comes first to remain loyal to tribal identity.

Sociologist Hugh Mackay offers helpful advice on balancing investment in service for the greater good with investing in life-giving relationships. He echoes the stoic view of how wisdom and living for a purpose greater than oneself is the fount of happiness: ‘fulfilling one’s sense of purpose, doing one’s civic duty, living virtuously, being fully engaged with the world and in particular, experiencing the richness of human love and friendship’.[58] Yet in The Art of Belonging, Mackay alludes to our need for community. He argues we should not be so focused on the issue of ‘Who am I?’ but should ask ‘Who are we?’.[59] Who are we? recognises the uniqueness of the military identity and mindset, and the importance of healing within community. Forgiveness requires emotional vulnerability and the desire to be connected with significant others. Forgiveness of self is a choice often born out of brokenness within the inner self. Mackay concludes:

This is the ultimate paradox of self-hood: when we get to the core of who we are, we find that just like everyone else, our essence is love—and what can love be about except connection and community.[60]

While serving beyond ourselves we need emotional connectedness with others. A risk of professional mastery leading to being hardened and stoic is that the focus on work and service are achieved to the exclusion of self and others. This is not everyone’s experience. Some become aware of the indoctrination or emotional downsides of their training and begin to question it. Many naturally grow in emotional awareness as they develop their broader identity as partner, parent and citizen.

Wherever the motivation comes from, the greater need during this stage of military life is connectedness—connecting with others (outside of the military tribe) and building interdependent relationships as well as connecting with self. Otherwise, the risk is that soldiers are hardened to be strong for service but also hardened in being disconnected from themselves and distant from their friends and families. The real casualties are often the families, partners and children deeply impacted by the vicarious effects of military service. Families sacrifice much on the altar of service. A saying of yesteryear was, ‘If the Army wanted you to have a wife [sic.] they would have issued you one’. Today it is more common to honour the importance of families, but the ongoing challenge is to nurture this aspect of life.

Giving and forgiving are intricately associated with connectedness and community, and echo again the topic of moral repair. Personnel suffering morally injurious events often cannot overcome a barrage of negative feelings, believing they are unworthy of forgiveness, particularly if they were the perpetrator. They then struggle to forgive others when they cannot forgive themselves. Often, the first step in this process occurs when a person feels safe within the trust of others (i.e., mates who have shared the same experience). Family and friendships outside Defence are also integrally important in soul repair.

Figure 2: Moral framing across the military life stages[61]

Stage 4—The Old Warrior (47+)

Old warriors are the fourth career life stage in our categorisation. We describe these as the 47-plus year olds approaching the end of their careers. They still have a lot to offer the ADF but also, importantly, have much to offer beyond it. The term old warrior is symbolic of the soldier who has grown beyond their youthful years, through professional mastery and the ‘hardened and stoic’ years and beyond. They may still exhibit professional mastery but they know their military years are limited and their focus shifts to transition beyond the uniform.

A mid-life task is to consider to what we have been giving our lives and to what we want to give the remainder of our lifetime. This can trigger reorientation of values and goals.

Erikson describes the task of middle adulthood (40–65) as developing generativity versus stagnation, and creating things that outlast one, including parenting children and contributing to the world.[62] As a life-stage theorist, he uses the term ‘ego integrity’, involving acceptance of one’s life as meaningful.[63] This is not just about work life and in fact often involves asking about identity and purpose beyond work. For ADF members with a compulsory retirement age of 60, these questions necessarily come earlier than they do for people in some other careers. As old warriors finish out their careers and approach retirement they still need to maintain a moral mindset, address any moral injuries and foster social connectedness, but additionally a key lesson to consider is legacy. In one sense this is an ultimate expression of knowing yourself and where you can best make a contribution, exercising self-control and giving of yourself to others and the world around.

Legacy

Transition and retirement from the ADF, and thinking about legacy, can occur during any stage of service life. But beyond age 47 a significant shift occurs in military careers, and identity in that transition will happen in the coming decade.[64] Looming transition triggers thoughts of what contribution members have made, what contribution they want to still make in Defence, and what and how they want to make the world a better place beyond it. Moreover, legacy is not entirely about what a person leaves behind; it is also about what they take with them—the Defence legacy. These are issues important for a person’s inner health and wellbeing, addressing the spiritual context of meaning, purpose and identity within the bio-psycho-social-spiritual model.

Many members move successfully into other spheres of service and duty, including contributing back to the Defence and veteran community. But some struggle with the loss of identity and the long, cumbersome process of transitioning.[65]

Legacy implies a lasting impact left behind after one leaves. What may matter more is sense-making and significance—defining the events and outcomes that matter most to the individual. These might not leave a lasting legacy organisationally, but they help shape a vision of one’s own life’s purpose and thus personal legacy.

Whether they are old warriors or young warriors or others transitioning, for soldiers to transition well requires deliberate planning and preparation. The process has improved greatly in recent times, through the allocation of a transition coach and information seminars. But the process does not necessarily guide members in meaningful self-reflection on matters of legacy. The longer a person has served, the more significant the need for reflection, particularly on legacy; however, deeper self-reflection usually occurs after a person has separated from the ADF. It is important for lessons on legacy to front-load information that will help members reflect on these important themes when the opportunity arises.

Conclusion

Moral framing provides a construct for personal character and leadership development guided by ADF values and behaviours. As a complement to ethical decision-making models and ethical armouring, it seeks to strengthen and protect the inner self, recognising the role of the human spirit as defined within the bio-psycho-social-spiritual model of health and wellbeing. Through the leadership tenets of know your self, control your self and give of your self, moral framing is about developing ethically and morally informed leaders—tailored to the demographics of military service and drawing on characteristics of life-span development theory.

This article has proposed four career stages of soldiers—beginning with the young warrior. Young warriors need a combat mindset, uniquely shaped to fit its purpose. But this needs to be foundationally a moral combat mindset, helping guide young warriors with the moral element for warfighting power to influence morale for the will to win and a thorough commitment to moral and ethical practice of the profession of arms.

The second stage for the career soldier is development of professional mastery. From hard training to operational experience and unconditional service, the oath to serve calls for sacrifice. But military service also brings risks of moral injury and therefore the need for attention to moral or soul repair.

The third stage is labelled ‘hardened and stoic’, which suggests both strengths and potential weaknesses. A bio-psycho-social-spiritual model of wholeness recognises the need for emotional connectedness and meaning-making beyond the uniform—underlining the importance of vulnerability and honesty at emotional levels with oneself and mates, and with family and friends beyond Defence.

The fourth stage is the old warrior. A key lesson for soldiers at this career stage is legacy—considering what they are leaving behind, what they want to take with them and how they want to continue to make a value-based positive contribution to their community and world.

We do not presume that these lessons are exclusive for that stage; nor are they the only lesson each stage needs. As with most theories, the stages are probabilistic rather than prescriptive.[66] We hope our analysis will prompt other and better plans for JPME and counselling for the profession of arms across military life stages. What is critical and what we want to continue to develop is how to foster the inner formation of the moral self for soldiers, tailored to the demographics of military service. We thus need some of our best thinking and training focused on how to best develop the moral inner self of our most important capability—our people—alongside giving them the best tools and trade competency for the profession of arms.

Acknowledgements

Ethics: Ethics clearance was not required for this research as no human participants were subject to invasive or non-invasive procedures.

Conflict of interest and funding: The first and second author currently serve as military chaplains within the Australian Army.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors, are unclassified and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Australian Army, the Department of Defence or the Australian Government.

Appreciation: In preparing this article, the authors appreciated conversations and editorial feedback from ADF Chaplains Stephen Brooks, Lindsay Carey, Karen Haynes, Matthew Stuart, Geoffrey Traill and Cameron West, as well as invaluable peer review feedback from three anonymous readers. All shortcomings are the responsibility only of the authors.

Endnotes

[1] Early discussion of officers as professionals included Samuel P Huntington, The Soldier and the State: The Theory and Politics of Civil–Military Relations (Harvard University Press, 1957), pp. 7–18; and Sir John Winthrop Hackett, The Profession of Arms: The 1962 Lees Knowles Lectures Given at Trinity College, Cambridge (London: The Times Publishing Company Limited, 1962), pp. 38, 40. Huntington equated officers with physicians and lawyers, while Hackett added holy orders and teachers to the list—an important nuance for this article focused on chaplaincy and teaching of morality. The ADF draws on General Hackett’s framework to underline the importance of codes of conduct. See Australian Defence Force, ADF-C-0 Australian Military Power, Edition 2 (2024), p. 69.

[2] LTGEN Simon Stuart, ‘The Challenges to the Australian Army Profession’, speech, Australian National University National Security College, 25 November 2024, transcript at: https://www.army.gov.au/news-and-events/speeches-and-transcripts/2024-11-25/challenges-australian-army-profession.

[3] Training Systems Branch, ‘Combat Behaviours’, The Cove (website), 24 May 2019.

[4] ADF Philosophical Doctrine 0 Series: Command, ADF Leadership, Edition 3 (2021); ADF Philosophical Doctrine 0 Series: Command, Military Ethics, Edition 1 (2021); ADF Philosophical Doctrine 0 Series: Command, Character in the Profession of Arms, Edition 1 (2023).

[5] For continuum stages see Joint Professional Military Education Directorate Australian Defence College, The Australian Joint Professional Military Education Continuum 2.0 (Canberra: Department of Defence, 2022).

[6] Deane-Peter Baker, Roger Herbert and David Whethem, The Ethics of Special Operations: Raids, Recoveries, Reconnaissance and Rebels (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2024), pp. 207–212.

[7] ADF, Character in the Profession of Arms, p. 1.

[8] ADF, Military Ethics, pp. 16–17. Virtue ethics examines ‘What sort of person should I be?’, in contrast to and balanced by duty ethics, or deontologicalism, which asks ‘Is the act right in itself?’, and just war and natural law theory, which examines just cause and right intention (ADF, Military Ethics, pp. 14–16).

[9] David Elliot, ‘The Turn to Classification in Virtue Ethics: A Review Essay’, Studies in Christian Ethics 29, no. 4 (2016): 477; Darren Cronshaw, ‘Good Soldiering and Re-virtuing Military Ethics Training’, International Journal of Public Theology 16, no. 3 (2022): 342.

[10] Cf. Mick Ryan, ‘Mastering the Profession of Arms, Part I: The Enduring Nature’, War on the Rocks, 8 February 2017; Mark Gilchrist, ‘What Defines the Profession of Arms?’, Australian Army Research Centre (website), 8 August 2016.

[11] ADF Land Domain Publication, LP 0.0.3 Chaplaincy in War, Edition 1 (2024), 2.3–2.5.

[12] The term ‘invisible underside’ is from Dan Pronk, Ben Pronk and Tim Curtis, The Resilience Shield: SAS Resilience Techniques to Master Your Mindset and Overcome Adversity (Sydney: Pan Macmillan, 2021).

[13] Mark Layson, Lindsay B Carey and Megan C Best, ‘Now More Than Ever: “Fit for Purpose”’, Australian Army Chaplaincy Journal (2023): 12–13 (11–23); Mark D Layson, Lindsay B Carey and Megan C Best, ‘The Impact of Faith-Based Pastoral Care in Decreasingly Religious Contexts: The Australian Chaplaincy Advantage in Critical Environments’, Journal of Religion and Health 62, no. 3 (2023): 1491–1512.

[14] Department of Defence and Department of Veterans’ Affairs, Defence and Veteran Mental Health and Wellbeing Strategy Consultation Draft (2024), p. 6.

[15] Susan P Robbins, Pranab Chatterjee, Edward R Canda and George S Leibowitz, Contemporary Human Behavior Theory: A Critical Perspective for Social Work Practice (Needham Heights MA: Allyn & Bacon, 2021); Alexa Smith-Osborne, ‘Life Span and Resiliency Theory: A Critical Review’, Advances in Social Work 8, no. 1 (2007): 152–168.

[16] John Dewey, How We Think: A Restatement of the Relation of Reflective Thinking to the Educative Process (Boston MA: DC Heath & Co, 1933).

[17] ADF, Leadership, p. 43.

[18] Definitions of Defence values are from ‘Values and behaviours’, Department of Defence (website), at: www.defence.gov.au/about/who-we-are/values-behaviours.

[19] Table 1: ‘Four military life stages’ was developed by the authors.

[20] The authors recognise that some personnel may have mastered their professional skills external to the ADF and enter at a later age (e.g. 30 years); however, they would still commence on entry at stage 1, ‘young warrior’. Alternatively, stages could be based on years of experience—i.e.:

- Stage 1: 1–4 years’ service: young warrior

- Stage 2: 5–10 years’ service: professional mastery

- Stage 3: 11–15 years’ service: hardened and stoic

- Stage 4: 16–20 years’ service: seasoned warrior

- Stage 5: 21-plus years’ service: old warrior.

[21] Jean Piaget, The Moral Judgment of the Child (Glencoe IL: Free Press, 1932); Erik H Erikson, Childhood and Society (New York: WW Norton & Co, 1950); LS Vygotsky, Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1978); Lawrence Kohlberg, Essays on Moral Development, Vol. I: The Philosophy of Moral Development (San Francisco CA: Harper & Row, 1981); James Fowler, Stages of Faith: The Psychology of Human Development and the Quest for Meaning (San Francisco CA: HarperCollins, 1995).

[22] Australian Defence College, Australian Joint Professional Military Education Continuum 2.0, pp. 16–17, 37–55.

[23] Inspector-General of the Australian Defence Force, Afghanistan Inquiry Report (2020), pp. 33, 325, 330, 334, 471–472, 499–502.

[24] Deane-Peter Baker, Morality and Ethics at War: Bridging the Gaps Between the Soldier and the State (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020).

[25] MAJGEN Chris Smith interviewed on ‘Warrior Culture’, The Cove (podcast), 24 February 2025, transcript at: https://cove.army.gov.au/article/cove-podcast-warrior-culture.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Christopher Coker, The Warrior Ethos: Military Culture and the War on Terror (New York: Routledge, 2007); Joseph O Chapa, Is Remote Warfare Moral? (New York: Public Affairs, 2022), pp. 63–64.

[28] Australian Defence College, Australian Joint Professional Military Education Continuum 2.0, pp. 16–17, 25–27.

[29] The military and combat mindsets are similar; however while the military mindset is common to all arms of service, the combat mindset is unique to warfighting capabilities, reflected primarily in the role of the infantry: ‘to seek out and close with the enemy, to kill or capture them, to seize and hold ground, repel attack, by day or by night, regardless of season weather or terrain’.

[30] Hackett, The Profession of Arms, pp. 15, 27, 40; discussed by Stuart, ‘The Challenges to the Australian Army Profession’.

[31] David Caligari and James Lewis, ‘The Combat Mindset: Increasing Lethality and Resilience’, The Cove (website), 4 July 2017, at: https://cove.army.gov.au/article/combat-mindset-increasing-lethality-and-resilience; discussed in Mark Biviano, ‘Mindset and Behaviours’, Smart Soldier 75 (2024): 18–23.

[32] Michael Evans and Alan Ryan, The Human Face of Warfare (Allen & Unwin, 2000).

[33] ADF, Chaplaincy in War, 2A-1.

[34] Commander of Forces Command Direction 11-21 Combat Behaviours.

[35] Sebastian Jünger, Tribe: On Homecoming and Belonging (London: 4th Estate, HarperCollins, 2016), p. 84.

[36] Australian Defence Force, Capstone Doctrine 0 Foundations of Australian Military Doctrine, Edition 4 (2021), p. 73.

[37] ADF, Australian Military Power, pp. 24–26; discussed also in ADF, Chaplaincy in War, 2A-24.

[38] Stephen Coleman, Military Ethics: An Introduction with Case Studies (New York: OUP, 2013), pp. 4–6.

[39] Vygotsky, Mind in Society; Saul McLeod, ‘Vygotsky’s Theory of Cognitive Development’, Simply Psychology (website), at: https://www.simplypsychology.org/vygotsky.html.

[40] ‘Adolescent Learning’, The Cove (website), 17 February 2022, at: https://cove.army.gov.au/article/adolescent-learning.

[41] Royal Commission into Defence and Veteran Suicide, Final Report Volume 1: Executive Summary, Recommendations and the Fundamentals (Commonwealth of Australia, 2024), pp. 34–41, 60.

[42] Australian Defence College, Australian Joint Professional Military Education Continuum 2.0, pp. 28–29.

[43] Smith-Osborne, ‘Life Span and Resiliency Theory’, p. 156; Erik H Erikson, Identity: Youth and Crisis (New York: WW Norton & Co, 1968).

[44] Timothy J Hodgson and Lindsay B Carey, ‘Moral Injury and Definitional Clarity: Betrayal, Spirituality and the Role of Chaplains’, Journal of Religion and Health 56 (2017): 1212–1228.

[45] ‘Moral, Religious or Spiritual Problem’ (Z Code 65.8)’, in American Psychiatric Association (ed.), Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition text revision (-5-TR) (Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2024).

[46] Australian Defence Force, ‘Moral Injury’, ADF Glossary (Canberra: Department of Defence, 2021).

[47] Timothy J Hodgson and Lindsay B Carey, Moral Injury: Pastoral Narrative Disclosure—An Intervention Strategy for Chaplaincy to Address Moral Injury, 3rd Edition (Canberra: Australian Government, Department of Defence, 2024).

[48] Lindsay B Carey, Matthew Bambling, Timothy J Hodgson, Nikki Jamieson, Melissa G Bakhurst and Harold G Koenig, ‘Pastoral Narrative Disclosure: The Development and Evaluation of an Australian Chaplaincy Intervention Strategy for Addressing Moral Injury’, Journal of Religion and Health 62 (2023): 4032–4071.

[49] Lindsay B Carey, Matthew Bambling, Timothy J Hodgson, Nikki Jamieson, Melissa G Bakhurst and Harold G Koenig, ‘Pastoral Narrative Disclosure: A Community Chaplaincy Evaluation of an Intervention Strategy for Addressing Moral Injury’, Health and Social Care Chaplaincy 12, no. 2 (2024): 165–190.

[50] Lindsay B Carey and Timothy J Hodgson, ‘Chaplaincy, Spiritual Care and Moral Injury: Considerations Regarding Screening and Treatment’, Frontiers in Psychiatry 9, no. 619 (2018): 1–10.

[51] Jan Grimell, ‘Ukrainian Military Chaplaincy in War: Lessons from Ukraine’, Health and Social Care Chaplaincy 12, no. 2 (2025): 139–149; see also Jan Grimell, ‘Ukrainian Military Chaplaincy in War: An Introduction’, Health and Social Care Chaplaincy 12, no. 2 (2024): 106–132.

[52] Australian Defence College, Australian Joint Professional Military Education Continuum 2.0, pp. 31–32. JPME Level 3 includes NCOs E8–E9A and Level 4 includes NCOs E9B–E9C.

[53] Frankl’s most enduring insight is acknowledgment that the forces beyond your control can take away everything you possess except one thing: your freedom to choose how you will respond to the situation. You cannot control what happens to you in life, but you can always control what you will feel and do about what happens to you. From Harold S Kushner in Victor Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning (Random House Group, 2004), p. 8.

[54] Jim Stockdale, Thoughts of a Philosophical Fighter Pilot (Stanford CA: Hoover, 1995).

[55] Nancy Sherman, Stoic Warriors, The Ancient Philosophy Behind the Military Mind (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005).

[56] Ibid., p. x.

[57] Ibid., p. 2.

[58] Hugh Mackay, The Good Life: What Makes a Life Worth Living? (Sydney: Macmillan, 2013).

[59] Hugh Mackay, The Art of Belonging: It’s Not Where You Live, It’s How You Live (Sydney: Macmillan, 2013), p. 5.

[60] Ibid., p. 30.

[61] Table 2: ‘Moral framing across the military life stages’ was developed by the authors in collaboration with Chaplains Lindsay Carey and Geoffrey Traill and illustrated by Geoffrey Traill.

[62] Erikson, Childhood and Society, pp. 240–241.

[63] Smith-Osborne, ‘Life Span and Resiliency Theory’, p. 156; Erikson, Identity.

[64] See ‘Transition Support for Members’, Department of Defence (website), at: https://www.defence.gov.au/adf-members-families/military-life-cycle/transition/transition-support-members; Department of Veterans Affairs, Veteran Support and Services Guide (Brisbane: DVA, 2025).

[65] Patrick Lindsay, Shining a Light—Stories of Trauma & Tragedy, Hope & Healing (Commonwealth of Australia, 2024), pp. 150–183.

[66] Smith-Osborne, ‘Life Span and Resiliency Theory’, p. 161.