Abstract

This article1 argues that thinking is more difficult than we might imagine. Explaining the purpose of thinking and examining some of the issues we all face, the author concludes that the Army has problems with thinking. We must address issues with the way we think as individuals, in teams and organisationally if the Army is to become truly adaptive.

... there are no positions in Army or the NAG [non-Army Group] that list critical thinking skills as either a desirable or mandatory requirement.2

Aman was driving along a country road when he realised he had a puncture in his kerbside front tire. As he pulled the car over, he noticed that he was outside a psychiatric hospital. He started to change the wheel: first, he loosened the wheel nuts on the wheel, and then jacked up the car. Next, he removed the wheel nuts and placed them within easy reach on the edge of the road. He then removed the wheel and took it to the back of the car, swapping it for the spare wheel. When he returned to the front of the car and placed the spare wheel on the ground, he accidently knocked the wheel nuts into a drain. As hard as he tried, he was unable to either remove the drain cover or reach the wheel nuts, tantalisingly out of reach. He sat down, put his head in his hands and wondered what he was going to do.

He soon realised that a patient from the hospital was standing nearby, watching him.

‘I suppose you think this is funny,’ said the driver.

‘No, I don’t,’ replied the patient.

‘I don’t suppose you could help me. I need to get to the next town for a meeting, but I don’t have any wheel nuts to attach the spare wheel to my car.’

‘Well,’ said the patient, ‘why don’t you just take one wheel nut off each of the other three wheels and use them to attach your spare wheel? That should work as long as you don’t drive too fast.’

‘That’s brilliant! It seems ironic that you’re a patient in a psychiatric hospital and yet you were able to think of a solution to my problem when I couldn’t.’

‘Yes,’ replied the patient, ‘but while I might be insane, I’m not stupid.’

Stupidity is failing to see an answer when it is plainly evident. Stupidity is behaving badly when the behaviour is obviously bad. Stupidity is making dumb decisions when the decision should have been recognised as dumb from the start. Stupidity is evidenced by the expression of dull and fallacious ideas and opinions. The obvious question to ask is: ‘How stupid are we?’ This article will suggest an answer.

But before suggesting an answer, I first need to contextualise thinking. The reason for this is that everybody has their own view of what they do with their thinking. And most people are wrong.

The Purpose of Thinking

| ‘I think therefore I am’ | ‘I am therefore I think’ |

| René Descartes | Australian Army Officers3 |

Thinking is something we take for granted. After all, we have been ‘thinking’ for our entire lives. Yet if we ask ‘What is the purpose of thinking?’, it is actually quite difficult to come up with an answer. I believe that thinking serves three broad and inter-related purposes: sensemaking, idea-making and decision-making.

Sense-making is what we do when we process data, information and the inputs from our physical senses. Sensemaking involves developing an understanding of ‘our’ world (as opposed to ‘the’ world). Sense-making can be broken down into understanding, learning and teaching. These aspects can be broken down further to include such activities as perception, memory, reasoning, communicating, analysis, logic and assimilating. While we have been making sense of our world since we were born, our ‘perception’ of the world is neither as accurate nor as reliable as we might think.

Idea-making is what we do when we seek to understand the context of our environment and generate ideas to inform decisions and action. Idea-making can be broken down into design and creativity. These aspects can be decomposed into such activities as inquiry, systems thinking, idea generation, synthesis and innovation. A broad range of techniques is available to enhance idea-making; but the Army has made little effort (a generous assessment) to institutionalise any of them.4

Decision-making is a natural consequence of thinking and leads to the actions we take. Decision-making involves problem solving, decision formulation and planning. These aspects can be broken down into such activities as recognising and diagnosing problems, selecting and applying a decision model, and formulating and executing plans. As with idea-making, there are a broad range of problemsolving and decision-making techniques. With the exception of the Military Appreciation Process (discussed later in this article), the Army has also failed to institutionalise them.5

These three ‘purposes’ describe the application of thinking, but not the demonstration of thinking. Thinking is demonstrated through expressions of thinking.

Expressions of Thinking

The quality of our thinking is expressed through the thoughts we have and the actions we take. The thoughts we have are usually expressed through speaking and writing. These expressions of thinking are judged by the people who listen to us speak or who read what we write. The actions we take are judged by those on whom they have an impact. In the Army, our thoughts are expressed through staff work, written or verbal. Our actions are judged by our subordinates, peers, seniors, partners, allies, enemies and, if we reflect on our experience, by ourselves. The judgments made on our actions are shaped by the perceptions, prejudices and biases of those making the judgments.6 We also need to consider that thinking occurs at different levels; it is not solely an individual activity.

Levels of Thinking

Thinking takes place on three levels: individual, team and organisational. Individual thinking is what we do independently of others. Individual thinking is shaped by various factors. These include the structure and functioning of our brains, the habits of thinking we develop, and the culture and expectations of the organisations and groups to which we belong.

Team thinking is the aggregation of individual thinking, but with the added complication of social and cultural interactions within the team. Bruce Tuckman, an American psychologist, is well known for his theory of group development, in which he identified five stages of development.7 The stages are forming, storming, norming, performing and adjourning. The importance of the stages is that they illustrate the effect and influence on individuals of group (team) development. When working in teams, individuals do not behave (think) as they would if they were acting as individuals.

Organisational thinking results from the aggregation of individual and team thinking and is constrained by the culture, traditions and rules that exist within the organisation. Organisational thinking can be viewed as resulting in direction given to, or influence exerted on, teams and individuals. Here we can make an interesting distinction between rational decision-making and rule following.8 Rational decision-making (on which the Military Appreciation Process is founded) is based on developing options, selecting the best option according to agreed (objective) criteria, and then implementing the selected option. Rule following, by contrast, requires decision-makers to identify the type of situation they face, to understand their position within the organisation, and to make a decision based on the rules and expectations of the organisation.

Having outlined the three levels on which thinking takes place, we can now turn our attention to some of the reasons why thinking is difficult.

Issues With Thinking

We humans share many issues with our thinking, and to explain them fully would take many books. For that reason I will only highlight four common issues that, in my experience, have a significant impact on our ability to think.

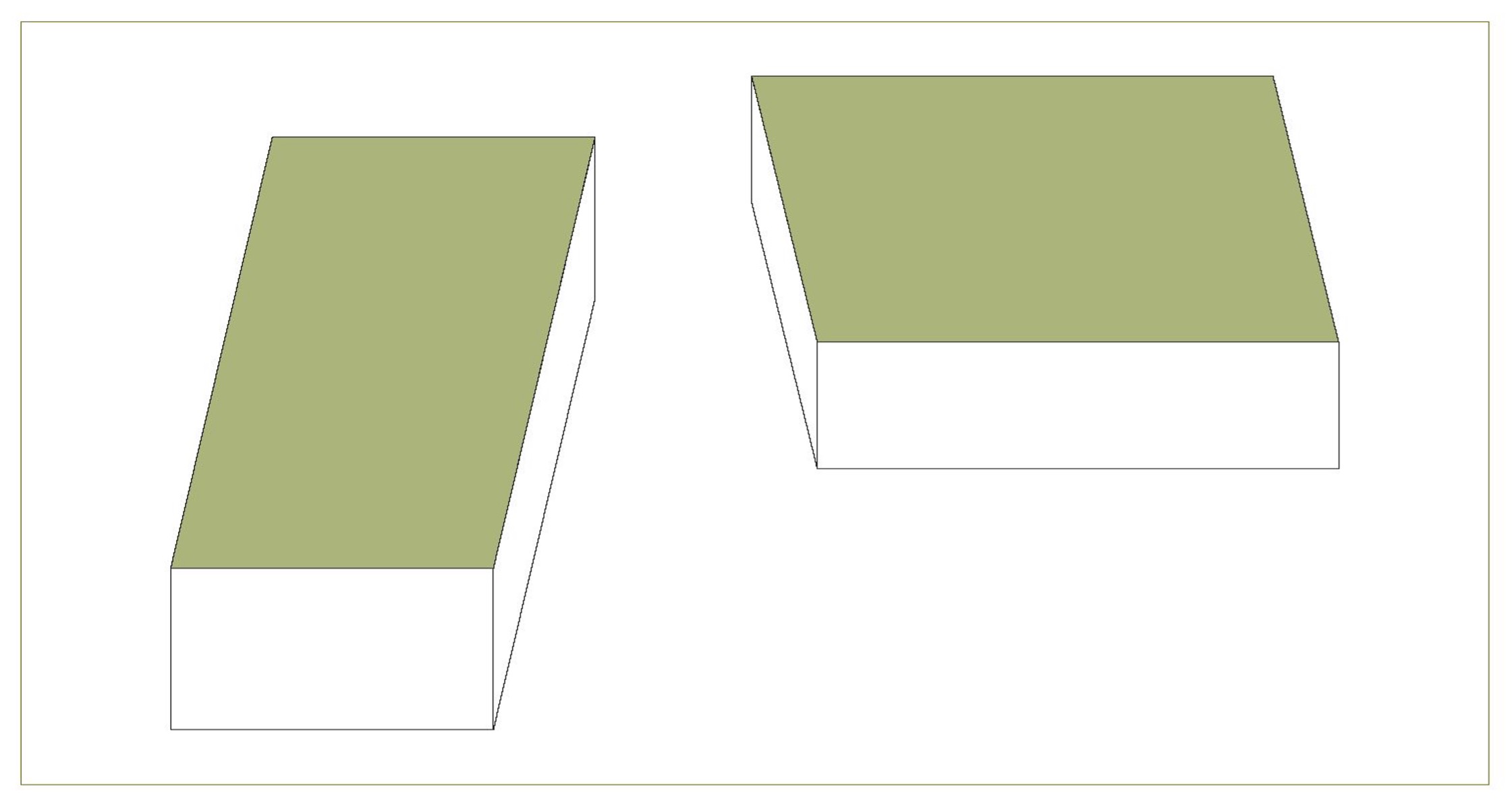

Perception. Although most of us believe that we perceive things as they actually are, evidence suggests that our perceptions are actually an interpretation by our brains of sensory information.9 What we think is real may not be. The world looks, feels, sounds, smells and tastes exactly as our brain imagines it to be. In Figure 1, the green surface on the left looks longer and thinner than the green surface on the right, yet they are the same size and shape (but 90 degrees out of alignment—measure them for yourself). Whether we like it or not, our brains play tricks on us.10

Figure 1. Spatial Perception

Our ability to ‘perceive’ what is happening around us is further impaired by issues such as ‘inattentional blindness’ and ‘change blindness’. Inattentional blindness is caused by our brain’s limited ‘awareness’ and results in our not noticing significant events taking place in plain view, but outside the focus of our attention.11 Change blindness is caused by our susceptibility to distraction and results in our not noticing significant changes in a scene we are looking at.12

The unreliability of perception means that we need to be careful when interpreting sensory inputs. What we think is happening may not be the same as what is actually happening.

Memory. The commonly held belief that our memory is a vast repository of everything we have experienced—and that we only need to access it to recall what took place—has been proven false.13 Memory is far less reliable than we might think. Our memory of events is a reconstruction, not a recording.

... considerable research indicates that our memories can change. We can even create new memories for events that never actually happened! In effect, our memory is not a literal snapshot of events which we later retrieve from our album of past experiences. Instead, memory is constructive. Current beliefs, expectations, environment, and even suggestive questioning can influence our memory of past events. It’s more accurate to think of memory as a reconstruction of the past—and with each successive reconstruction, our memories can get further and further from the truth. Memories thus change over time, even when we’re confident that they haven’t, and those memories can have a significant influence on the beliefs we form and the decisions we make.14

The fallibility of memory has the worrying potential to shape our perceptions, to influence our understanding of events, and to impact on the quality of individual and team decisions.

The challenge for career managers is to stop posting people simply to fill vacant positions and to start planning career pathways that result in the accumulation of relevant memories. The value of qualifications is wasted if the holder is unable to reinforce learning through relevant experience and continuing development. My experience, and I’m confident I’m not alone, is that the qualifications I gained have been largely irrelevant to my career management.15

Creativity. Creativity is a critical requirement for adaptation. We need creativity because:

When things change and new information comes into existence, it’s no longer possible to solve current problems with yesterday’s solutions. Over and over again, people are finding out that what worked two years ago won’t work today. This gives them a choice. They can either bemoan the fact that things aren’t as easy as they used to be, or they can use their creative abilities to find new answers, new solutions, and new ideas.16

The problem we all face, however, is that creativity is generally conditioned out of us by our system of education and our social and work cultures. Tradition, in particular, has become a yoke around our necks. Tradition is not a valid argument for preserving the past: traditions remain valuable only if they remain relevant. If you want an illustration of the power of tradition to stymie creativity and innovation, try suggesting that we should reduce the amount of drill we do.

The only thing harder than getting a new idea into the military mind, is getting the old one out.

- B H Liddell Hart

The good news is that, regardless of how ‘uncreative’ we might feel we have become, we are still capable of producing creative solutions.

... even if it’s not possible to train people to be more creative (and I think it is), it is possible to supply them with tools that will allow them to produce creative solutions without necessarily being creative.17

The tools for producing creative solutions are well established and relatively easy to learn. As mentioned previously, the problem that Army currently has is that we fail to incorporate these tools into our decision-making processes. My opinion is that Army’s leaders are uncomfortable with the uncertainty of creativity. It is much easier to pursue a safe, dull plan than to try to do something new.

Confirmation bias. None of us is as brilliant or as infallible as we think we are. Confirmation bias leads us to seek out evidence to confirm beliefs we already hold. Either we do not look for dissonant (disconfirming) evidence, or, if we stumble across it, we discount its relevance. This is a major problem in the thinking of individuals.

Faced with the choice between changing one’s mind and proving that there is no need to do so, almost everyone gets busy on the proof.

- John Kenneth Galbraith

Worryingly, there is even evidence that confirmation bias is hard-wired into our brains.

Neuroscientists have recently shown that these biases in thinking are built into the very way the brain processes information—all brains, regardless of their owners’ political affiliation. For example, in a study of people who were being monitored by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) while they were trying to process dissonant or consonant information about George Bush or John Kerry, Drew Westen and his colleagues found that the reasoning areas of the brain virtually shut down when participants were confronted with dissonant information, and the emotion circuits of the brain lit up happily when consonance was restored. These mechanisms provide a neurological basis for the observation that once our minds are made up, it is hard to change them. 18

Confirmation bias has a major impact on the quality of our individual and team thinking. It is the main reason we so often miss what in hindsight were obvious flaws in our decisions.

I have so far avoided a direct answer to my earlier question: ‘How stupid are we?’ The answer, based on the evidence I have seen, is that we are rather stupid. I can imagine you asking, ‘Who are the stupid people?’ Well, if you want to know who the stupid people are you need only look in a mirror. I have outlined the four problems with thinking which impact directly on all individual thinking. They also affect team thinking through their impact on the individuals who form the team. These problems (and many more) also affect organisational thinking through the aggregation of individual and team effects.

Facilitation - Now There's An Idea!

The Army is a team-focused organisation. Teams define who we are and generate the most important components of our capability. Army’s leaders, at all rank levels, are excellent at leading.19 They are inspirational and skilled at eliciting Herculean efforts from team members towards achieving the team’s objective. The problem that most teams have with ‘thinking’, however, is that they do not know how to do it—as a team. Team thinking requires the application of process and technique. This is in contrast to team ‘doing’, which can be achieved through coordinated effort and following procedure. Team thinking in the Army is hamstrung by a surplus of leadership and a deficiency of facilitation.

This lack of facilitation skills also affects training. While we have excellent instructors—with great technical knowledge and confident manner—the vast majority of them have not been trained to facilitate. Facilitation requires you to help a team (or an individual) to get the most out of an activity. It is hard to do this if you have an ‘alpha-type’ personality and no practical facilitation skills. A skilled facilitator appreciates the importance of planning an activity and guiding the team in the use of a wide range of appropriate techniques. A skilled facilitator understands that team thinking is a process and not an event.

When I teach brainstorming to groups I start by asking how many people have ‘done’ brainstorming in the past. Almost everybody raises his or her hand. After I have taught the process of brainstorming, I ask the question again. Typically, less than ten per cent of people then raise their hands. What most of them have done in the past can best be described as ‘brain dumping’—the simple dumping of ideas related to the nominated topic. Brainstorming requires preparation and the conduct of a sequenced arrangement of activities to generate ideas, sort the ideas, evaluate the ideas and develop options. The full process of brainstorming can take as long as several months and should incorporate the use of additional techniques such as nominal group technique and affinity diagrams. You can do brainstorming in a much shorter timeframe, but if you think you can complete it within half an hour, you’re deluded. If your entire experience of brainstorming has been confined to sitting down for 15-20 minutes with three or four colleagues in a small room, with a whiteboard and a couple of markers, then you have actually never experienced brainstorming. And that is indicative of the difference between leadership and facilitation. A leader will lead a team to his or her decision. A facilitator will help the team to find better decisions for themselves.

If the Army is to become adaptive it will need to adopt a more facilitative approach to teamwork. This will provide a challenge to Army’s leaders who, based on their experience, will probably think that they can do the job just fine without the need to change their successful, directive style of leadership.

THE PROBLEM WITH THE MILITARY APPRECIATION PROCESS

If the only tool you have is a hammer, you tend to see every problem as a nail.

- Abraham Maslow (1908-1970)

The Military Appreciation Process (MAP) is the only decision-making framework we have in the Army. It is based on the rational decision-making model, but is often applied more as a planning tool than a decision-making framework. A significant problem is that the majority of people using the MAP lack a deeper knowledge and understanding of how ‘thinking’ takes place. They are unaware of the limitations we all have when trying to make sense of our environment. They are also unaware of the problems we all face when trying to make decisions. Because they lack self-awareness, they are therefore compelled to apply the MAP as a linear process, without fully understanding the implications of our limited ability to think. Even those who are experienced in the use of the MAP may simply be applying the process in a more efficient way by varying the application of the doctrine to suit different situations. They are working the ‘process’ smarter, but not necessarily making smarter decisions.

An even more significant problem, and one which pretty much invalidates the quote I chose to open this section, is that most people in the Army do not even use the MAP to guide everyday decision-making. Of course, when you ask them if they use it they will say that they do; but scratch the surface of their response and you will see how shallow it is. They skimp on the Intelligence Preparation and Monitoring of the Battlespace, shortcut the Mission Analysis and leap straight in to developing a favoured (i.e. ‘I’ve done it before and it worked then’) course of action. Then, a year or two after implementation, as the detailed plan of action stumbles over unintended consequences, we find that the person who chose it has been posted out and fails to learn from the experience. Perhaps I should replace the Maslow quote with one (less elegant) of my own:

If the only tool you have is a hammer, and you choose not to use it, then either you recognise the need for additional tools or you are stupid.

- Richard King

When the Australian Military Appreciation Process (MAP) doctrine was first published in 199620 it was 181 pages long. Five years later, on schedule, the doctrine was rewritten,21 but now it was 292 pages long. Eight years later, a new version is due to be released in October 2009, as developing doctrine: the current draft is 592 pages long. I am not entirely convinced that the added length will either make the MAP any more useful or encourage its use. Also worrying is that the rewritten MAP will still lack a decent range of tools to improve its application.

Let me digress briefly, and suggest an insight into the management and use of doctrine by Army. If the Army is to become adaptive it will have to change the way it thinks about doctrine. The best we can achieve with doctrine is to ‘habitualise’ what we thought we had to do at a time in the past when we wrote the doctrine. Doctrine that takes years to review, produce and validate is out of date and representative of an outdated paradigm. All doctrine should be ‘developing doctrine’, and subject to continuous review and improvement. Currently, doctrine entrenches what we did do. We can only become adaptive if we encourage a focus on what we could do; but that would require creativity and innovation.

Some Evidence of Sub-Optimal Thinking

Up to now, I have provided my judgment22 on why it is difficult to think. It is probably time to provide some evidence of sub-optimal thinking.

My office windows. On 28 July 2009, I was away from my office for the day. When I opened the door the next day, something did not look right. I discovered that of the six windows in my office which could be opened, two had been fitted with window locks (which were locked, and for which I did not have a key) and the remaining four had been riveted closed. I had not known this was scheduled to be done, and neither had anyone else I spoke to in the building. Still, I comforted myself, the work must have been done for a good reason. And so what if our building lacks the amenity of air-conditioning and, by all accounts, becomes uncomfortably hot in summer; at least my windows wouldn’t accidentally open.

Two weeks after my windows were sealed, the same worker (I had not met him when he sealed the windows, but he said he was the same person) came back to unlock the window locks and drill out all the rivets he had fitted previously. He worked for a contractor and did not know why the decision was made to seal the windows originally, or unseal them two weeks later. He was being paid so he was happy.

Now, noting that it is a requirement to report on adaptive traits or contributions towards the Strategic Reform Program, I have a suggestion. If Defence would like to improve its chances of saving 20 billion dollars over the next ten years, it could start by making less stupid decisions, such as sealing the windows in a non-air-conditioned building.

Writings on the Adaptive Army. Calling the Army adaptive does not make it adaptive. A change in title—even accompanied by a change in organisational structure—does not change habit, culture or tradition. Furthermore, explaining how we are going to become an Adaptive Army in documents that are poorly written—from a critical thinking perspective—may be counterproductive.

I visited the Adaptive Army’ webpage and analysed the introductory text and the explanations of the five initiatives. To do this I used the ‘grammar’ tool in Microsoft Word to show the readability statistics for each piece of text. The results were uninspiring. The statistics are shown below:

Grammar Tool Statistics for Adaptive Army Homepage

| Criterion | Introduction | Rebalance C2 & Army Structure | Personnel Initiatives | Improved Training & Education | Materiel Management | Army Knowledge Management |

| Total words | 385 | 1170 | 502 | 685 | 615 | 424 |

| Sentences per paragraph | 3.2 | 3.8 | 6.6 | 4 | 3.8 | 2.6 |

| Words per sentence | 24.0 | 21.5 | 25.1 | 16.1 | 32.3 | 19.6 |

| Passive sentences | 12% | 22% | 20% | 22% | 26% | 23% |

| Flesch Reading Ease | 19.1 | 21.4 | 22.3 | 26.2 | 19.7 | 22.2 |

| Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level | 16.5 | 15.5 | 15.8 | 13.6 | 18.5 | 15.0 |

Interestingly, the best-written section (Improved Training & Education) still requires the reader to be at least partly university educated in order to understand what is written. The writing shows a lack of appreciation for the intended audience, unless it is written only for those in Army with a university education. This provides further evidence in support of Colonel John Hutcheson’s statement in the last edition of the Australian Army Journal: ‘I have found that the majority of officers can verbalise their ideas, but have great difficulty in expressing those same ideas on paper.’23 I would go further. I believe that the majority of officers are confident and competent speakers, but that their speaking skills mask an underlying problem with thinking. This can result in officers expressing forceful, persuasive, but dull opinions and ideas that are given greater credibility than they deserve if analysed from a critical thinking perspective.

Further evidence of the difficulty people have in expressing ideas in writing is found in CA Directive 14/09, Implementing the Adaptive Army in 2009 - AL1. Consider paragraph 9 from that directive:

Adaptive Army is founded on the principle that although Army’s hierarchical structure remains crucial to our culture, the right application of modern technology can empower individuals and the chain of command through higher levels of personal responsibility and communication. Adaptation at its heart balances the need to change as the situation evolves with a requirement to retain important corporate knowledge.

Before commenting on this from a ‘thinking’ perspective, I acknowledge that any analysis of an extract in isolation from the whole document carries the risk of missing important context. My comments on this paragraph can be summed up as: it fails to show much evidence of critical thinking. Specifically:

a. It confuses ‘principle’ with ‘assumption’. Army’s hierarchical structure is a cultural inheritance. A hierarchical structure has historically proven effective for command and control. It contributes to tactical, operational and strategic success when armies are large, ponderous and complicated. In a non-operational environment, however, or a lower-level and more-complex type of operation, a flatter (less hierarchical) structure would be more adaptive and would encourage greater creativity. It is an assumption that ‘Army’s hierarchical structure remains crucial to our culture’, and one that should be challenged.

b. It misrepresents the meaning of ‘empowerment’. The notion that ‘the right application of modern technology can empower individuals and the chain of command through higher levels of personal responsibility and communication’ is another assumption. Technology cannot empower individuals and the chain of command. Empowerment requires that individuals (and organisations) have devolved to them the right combination of responsibility, authority to act, and the resources to complete the job. This is a cultural issue, not a matter of technology. Army has traditionally been strong on devolving responsibility but weak on devolving authority.24 A culture of mission command should be at the heart of achieving an Adaptive Army, and yet ‘mission command’ is not mentioned in the Directive.25

c. If we ignore the suspect use of ‘empowerment’, it still does not make much sense. How will ‘the right application of modern technology’ achieve anything through ‘higher levels of personal responsibility and communication’? Most people already have adequate levels of personal responsibility and are in almost constant communication with anybody with a computer terminal and a telephone. Has issuing Blackberries to senior officers really empowered them? As Robert Townsend writes in his book, Up The Organization, ‘Make sure your present report system is reasonably clean and effective before you automate. Otherwise your new computer will just speed up the mess.’26

d. It exhibits poor critical thinking. ‘Adaptation at its heart balances the need to change as the situation evolves with a requirement to retain important corporate knowledge.’ The use of the word ‘balances’ implies a direct relationship between ‘the need to change’ and the retention of ‘important corporate knowledge’. While this links nicely into the next paragraph in the CA Directive, it is evidence of sub-optimal thinking. Adaptation is about recognising the need to change, and then having the will and the means to change. Corporate knowledge resides in the heads of people; not in a database on a computer. Change will always require ‘change’. The problem with corporate knowledge is that it needs to be developed, built and applied. Every time you post someone to another (different) part of the Army their corporate knowledge walks out of the door with them. The Chief of Army’s intent is that ‘The Army must continually review and adapt to ensure that it remains fit for the changing environment’. Adaptation means changing. This sentence would have made more sense if it stated: Adaptation at its heart recognises the need to change as the situation evolves and the challenges this poses to the development and management of corporate knowledge.

While my issues with office windows and the quality of writing relating to the Adaptive Army initiative probably seem like scant evidence of poor thinking in Army, they are merely symptomatic. We have a long history of making stupid decisions with the best of intentions. For those interested in revisiting some of that history I highly recommend reading the book Reglomania.27

Conclusion

So, is the Army stupid? I believe it is. That does not mean, however, that everybody in the Army is stupid, or that everything the Army does is stupid. My assessment is that we are stupid as individuals because we do not understand ‘thinking’. We do not appreciate how many problems we face in trying to make smart decisions. Increased self-awareness through education and training is part of the solution for individuals. Through deliberate effort, individuals can learn to raise the recognition threshold for stupid ideas.

Teams face additional problems resulting from Army’s culture. Tradition and rank hamper the development and free exchange of ideas.28 A focus on leadership instead of facilitation prevents teams from reaching their true potential. Facilitation skills are an essential ‘adaptive’ skill, but if Army decides to ‘up skill’ its people in this area we are starting from a very low base.

Organisationally we need to put more effort into thinking. This will not, however, slow down the process of adaptation. It may actually speed things up if we make fewer decisions that are eventually found to be stupid and which result in considerable rework. Here we face another cultural problem: Army’s culture is fixated on achieving ‘end-states’ (completing things) when we should be focused on monitoring ‘achievement’. The Army focuses too much on delivering outputs and too little on achieving outcomes.

Ultimately, it will be very hard to become less stupid if we do not recognise the value of critical and creative thinking skills and facilitation skills, and establish a robust system to develop, recognise and reward those skills. Those of you uncomfortable with the thought that we might be stupid can console yourselves with the fact that, as you read this, critical thinking skills are neither a desirable nor a mandatory requirement. The rest of you might think that the time has come when they should be.

Endnotes

1 This article summarises some key conclusions drawn from a decade of experience in the development of thinking skills.

2 Quote by a career manager from the Directorate Officer Career Management - Army.

3 This applies equally to just about anybody. I am highlighting Army officers to make a point.

4 Some of the idea generating techniques ignored by the Army are covered in the following: Edward De Bono, Serious Creativity, Fontana, London, 1992; Michael Michalko, Thinkertoys – A handbook of creative-thinking techniques, Second Edition, Ten Speed Press, Berkeley, 2006; Arthur B VanGundy, Idea Power - Techniques & Resources to Unleash the Creativity in Your Organization, AMACOM, New York, 1992.

5 For an overview of some of the problem-solving and decision-making techniques ignored by the Army I recommend the following two books: William J Altier, The Thinking Manager’s Toolbox - Effective Processes for Problem Solving & Decision Making, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1999; Morgan D Jones, The Thinker’s Toolkit - 14 Powerful Techniques for Problem Solving, Three Rivers Press, New York, 1998.

6 If the Army wishes to improve the quality of performance reporting on personnel then some form of 360 degree reporting will be required. Our superiors only have a myopic view of the outcomes of our thinking.

7 Robert P Vecchio, Greg Hearn and Greg Southey, Organisational Behaviour - Life at Work in Australia, Harcourt Brace & Company, Sydney, 1995, pp. 381-83.

8 James G March, with the assistance of Chip Heath, A Primer on Decision Making -How Decisions Happen, The Free Press, New York, 1994, pp. 1-3, 57-61.

9 Atul Gawande, ‘The Itch’, The New Yorker, 30 June 2008, <http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2008/06/30/080630fa_fact_gawande/> accessed 27 August 2009.

10 Graham Lawton, ‘Mind tricks: Six ways to explore your brain, The New Scientist, 19 September 2007, <http://www.newscientist.com/article/mg19526221.300-mind-tricks-six-ways…; accessed 26 August 2009.

11 Michael Shermer, ‘None So Blind’, Scientific American Magazine, March 2004, <http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=none-so-blind> accessed 8 September 2009.

12 J Kevin O’Regan, ‘Change Blindness’, Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science, <http://nivea.psycho.univ-paris5.fr/ECS/ECS-CB.html> accessed 8 September 2009.

13 If you want more evidence of how unreliable our memories are, then I recommend reading the following: Gary Marcus, Kluge: The haphazard construction of the human mind, Houghton Mifflin Company, New York, 2008, Chapters 2 and 3; Robert A Burton, On Being Certain: Believing You Are Right Even When You’re Not, St Martin’s Press, New York, 2008, Chapters 2 and 8; Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson, Mistakes Were Made (but not by me): Why We Justify Foolish Beliefs, Bad Decision, and Hurtful Acts, Harcourt Inc., Orlando, 2007, Chapter 3; Daniel L Schacter, The Seven Sins of Memory, quoted in <http://brothersjudd.com/index.cfm/fuseaction/reviews.detail/book_id/251…; accessed 17 April 2009.

14 Thomas Kida, Don’t Believe Everything You Think: The 6 Basic Mistakes We Make in Thinking, Prometheus Books, New York, 2006, p. 22.

15 In 1988 I majored in industrial relations but was never employed in personnel management; the qualification is now virtually worthless, although some fragments of information remain in my memory.

16 Roger von Oech, A Whack on the Side of the Head: How You Can Be More Creative, Warner Books, New York, 1998, p. 5.

17 Roni Horowitz, Introduction to ASIT, published as an ebook by Start2Think, 2003, p. 4.

18 Tavris and Aronson, Mistakes Were Made (but not by me), p. 19.

19 For those interested in ‘argument’, I am providing an example of inductive reasoning: generalising from a number of observations. Inductive arguments are not ‘valid, only more or less probable. For a fuller explanation see: Nigel Warburton, Thinking from A to Z - Third Edition, Routledge, London, 2007, pp. 85-86.

20 Australian Army Training Information Bulletin, Number 74, The Military Appreciation Process, Department of Defence, 18 December 1996.

21 Australian Army Land Warfare Doctrine, LWD 5-1-4, The Military Appreciation Process, Department of Defence, 2001.

22 I hope that the reader will give me some credit for eleven years of work in this area, and assess my arguments as reasoned judgment rather than mere opinion.

23 Colonel John Hutcheson, ‘The Adaptive Officer: Think, Communicate and Influence’, Australian Army Journal, Vol. VI, No. 2, 2009, p. 10.

24 I am commenting from a ‘staff’ perspective here, rather than an operational one.

25 Mission command was one of three focus themes in the Chief of Army’s Exercise in 2006. The proceedings from that exercise concluded: ‘Overwhelmingly, the feedback from syndicates highlights that a significant amount of work remains to convey the vision of mission command throughout the organisation.’ Scott Hopkins (ed.), Chief of Army’s Exercise Proceedings, Land Warfare Studies Centre, Canberra, 2007, p. 127.

26 Robert Townsend, Up The Organization – How to stop the company stifling people and strangling profits, Coronet Books, Hodder-Fawcett Ltd, London, 1971, p. 34.

27 Roy Gilbert, Reglomania: The curse of organisational reform and how to cure it, Prentice Hall, Melbourne, 1991, pp. 30-31. Those with long corporate memories will remember warmly the era of paying a premium to have air conditioners and radios removed from cars because the intended users were not entitled to them. Likewise, paying for the modification of existing plans for married quarters, to remove ensuite bathrooms because the intended occupants had no entitlement—only to pay even more to have ensuite bathrooms added to the houses when the standards changed.

28 A simple and effective tip for leaders when working with a team is to ask the most junior members of the team to share their ideas and opinions first. If the boss speaks first, most of their subordinates will find it hard to disagree.