Abstract

This article contends that the Army’s Adaptive Campaigning - Future Land Operating Concept has important implications for the Army’s doctrine, culture and officer education because, despite recent updates, current and developing doctrine has not yet fully reconciled some legacy linear concepts with Adaptive Campaigning’s non-linear foundations. While doctrinal metaphors and planning methodologies such as ‘centre of gravity’ and the Military Appreciation Process have enduring relevance, the imperative to deal with complex problems demands a more sophisticated approach to operational art and design.

There is always an easy solution to every human problem—neat, plausible, and wrong.

- Menken

Introduction

Adaptive Campaigning - Future Land Operating Concept states:

... much existing Joint and Army doctrine tends to be focussed on the direct force-on-force encounters with the concept of a singular Centre of Gravity being one example. [Adaptive Campaigning] describes an environment in which this will not always be the case. 1

This statement is a direct challenge to some of the Army’s conventional wisdom. The statement reflects the notion that simple mechanical metaphors such as ‘centre of gravity’ have limited applicability to complex problems. Adaptive Campaigning argues that complex problems will be the norm rather than the exception in contemporary warfare, which will be characterised by multiple and diverse actors operating in complex terrain, leveraging the rapid diffusion of new technologies and highly lethal modern weapon systems to influence the allegiances and behaviours of individuals, groups and societies. This has important implications for the way the Army interprets operational problems, thinks about them, develops solutions to solve them and directs forces to execute solutions.

Adaptive Campaigning is a response to the evolving character of warfare. It provides a philosophical framework for resolving armed conflicts in complex operating environments and describes the ‘actions taken by the Land Force as part of the military contribution to a whole of government approach’.2Adaptive Campaigning is the product of several years of work. Its key themes are: the influencing and shaping of perceptions, allegiances and actions of populations through a persistent, pervasive and proportionate response; the orchestration of a whole-of-government effort across five interdependent and mutually reinforcing conceptual lines of operation; warfare as a continuous meeting engagement and competitive learning environment requiring a flexible, agile, resilient, responsive, and robust land force; the fundamental requirement for close combat; and a command climate that challenges understanding and assumptions, founded in the philosophy of ‘Mission Command’.

The purpose of this article is to highlight some of Adaptive Campaigning’s implications for the Army in order to generate some discourse to support the development of an implementation plan. This article does not address all of Adaptive Campaigning’s implications, many of which are addressed by ongoing initiatives. Instead, it looks into Adaptive Campaigning’s implicit logic, where some of the most significant implications lie. This article contends that Adaptive Campaigning has important implications for the Army’s doctrine, culture and officer education because, despite recent updates, current and developing doctrine has not yet fully reconciled some legacy linear concepts with Adaptive Campaigning’s non-linear foundations.

The article assumes that the reader has a basic understanding of Adaptive Campaigning and begins by describing the differences between linear systems and complex adaptive systems. It then discusses the tensions and inconsistencies between Adaptive Campaigning and elements of Land Warfare Doctrine, specifically linear and mechanical metaphors such as ‘centre of gravity’, ‘end-state’, ‘lines of operation’ and the ‘Effects-Based Approach’. The article then illuminates the limitations of doctrinal methodologies for designing and planning operations and campaigns to deal with complex problems, and posits that the US Army approach to campaign design might provide a basis for taking corrective action. The article concludes by contending that, while most of the legacy metaphors and planning methodologies have enduring relevance, the imperative to deal with complex problems demands a more sophisticated approach to operational art and design, which will have immediate implications for officer education and the Army’s doctrine and culture.

Complex Adaptive Systems, Linear Systems, And Land Warfare Doctrine

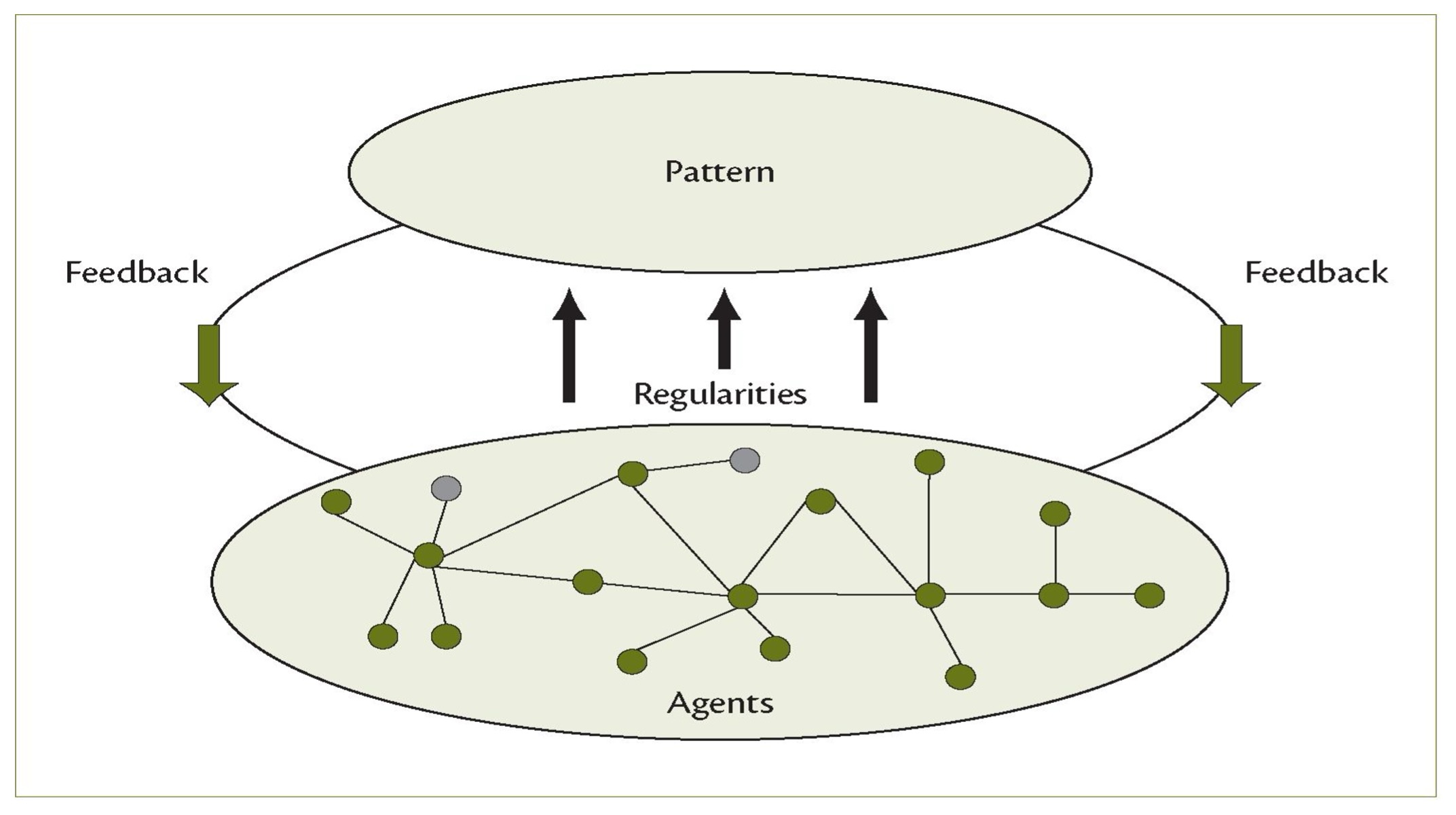

Adaptive Campaigning has a thorough grounding in strategic and military history. Nevertheless, in light of the complexity of the contemporary battlespace, it also draws on the relatively new science of complex systems. A complex adaptive system is one ‘whose properties are not fully explained by an understanding of its component parts’.3 Complex adaptive systems are inherently unpredictable. Interdependent components of the system interact with each other in unpredictable ways. Discernable patterns and properties emerge from this mass of apparently random interactions at different levels and scales, which feed back into the system and influence the interactions of the agents themselves, as shown in Figure 1. Examples of emergent behaviour are the complexity and regularity of a termite mound, a flock of birds and warfare. All are characterised by patterns and regularity despite the absence of a single grand plan.4

As the environment within any complex system changes, agents and populations must change to ensure best fit. Any adaptation by an agent or population changes the environment, which in turn changes the agents and so on. Consequently, best fit is a transient state. Sometimes changes cause an imbalance in the system, resulting in a period of instability. For example, when a counterinsurgent wrests control of an area from an insurgent, the balance of power and the nature of relationships in that area change, resulting in a period of flux before a new balance emerges. The form of the new balance is emergent and unpredictable.6 The ability of an agent or population to adapt determines its success within the system. Not surprisingly, there are strong similarities between this description of complex systems and Carl von Clausewitz’s and Thucydides’ descriptions of war.

Figure 1. Complex Adaptive Systems5

Adaptive Campaigning is inconsistent with the Army’s Land Warfare Doctrine because important parts of Land Warfare Doctrine have a conceptual basis in linear and mechanical metaphors rather than complex systems theory. This linear tendency is, by and large, a by-product of the US Army’s post-Vietnam catharsis and its subsequent rediscovery of operational art in the 1980s, when mechanical systems were a dominant paradigm. Unlike complex adaptive systems, the injection of energy into a linear system has a proportionate effect on the system, and knowledge of the initial conditions of a linear system allows for accurate prediction. Examples of linear systems are computers, telecommunications networks and ground-based air defence systems. Warfare, on the other hand, is non-linear. When linear logic is applied to a non-linear system, such as in war, the results tend to be counterintuitive because outcomes defy proportionality.7 For example, a single rocket propelled grenade strike on a Blackhawk helicopter in Mogadishu in October 1993 had disproportionate and unpredictable tactical, strategic and policy consequences. Therefore, mechanical and linear metaphors such as ‘centre of gravity’, ‘end-state’, ‘lines of operation’ and the ‘effects-based approach’ are inconsistent with Adaptive Campaigning.

Centre Of Gravity

The metaphor from which much of Land Warfare Doctrine derives its logic is ‘centre of gravity’. Doctrine defines ‘centre of gravity’ as ‘characteristics, capabilities or localities from which a nation, an alliance, a military force or other grouping derives its freedom of action, physical strength or will to fight’.8 It is a reduction hypothesis that assumes military problems and military forces have a single point of control.9 It makes a problem easy to deal with because it assumes that by addressing one or two things the ‘solution to all other problems will follow automatically’. Professor of Psychology, Dietrich Dorner, argues:

A reduction hypothesis of this kind, tying everything to one variable, has, of course, the positive virtue of being a holistic hypothesis, which is desirable because it encompasses the entire system. But it does so in a certain way, namely, by reducing the investment of cognitive energy.10

Dorner claims that this type of hypothesis fails because it does not account for the unpredictable relationships between actors and the manifold feedback loops in a complex adaptive system.11 Adaptive Campaigning accepts Dorner’s claim, stating:

While the Centre of Gravity construct remains valid to achieving an understanding of the key targetable critical vulnerabilities that exist ... it is important to realise that each of the multiple actors and influences involved in the conflict may themselves have one or more Centres of Gravity.12

Complex problems have no central point of control. Still, the ‘centre of gravity’ metaphor is not without utility. There are many simple military problems, more often than not at the tactical level, for which ‘centre of gravity’ might apply. A straightforward battalion attack against a like adversary is one such example. However, the ‘centre of gravity’ metaphor is not universally applicable. Land Warfare Doctrine does not acknowledge the metaphor’s limited domain of applicability. This lack of sophistication is likely to lead to flawed thinking about complex problems.

End-State And Lines Of Operation

The associated concepts of ‘end-state’ and ‘lines of operation’ (as defined in doctrine, not Adaptive Campaigning) are also inconsistent with Adaptive Campaigning because they, too, are linear metaphors. End-state is ‘a term used to describe a commander’s desired outcome for the operation or the state which the commander wishes to exist when the operation is complete’.13 Lines of operation is accorded two different meanings in developing Land Warfare Doctrine. In one instance, the use of the term is the same as Adaptive Campaigning, meaning interdependent domains of action that provide a conceptual framework for the conduct of operations.14 In the second instance, lines of operation are described as something ‘identified during operational design and defined during the planning process to progress towards the campaign goal through decisive points’.15 In the second instance lines of operation are a linear pathway, leading to an end-state.

End-state and the pathway interpretation of lines of operation are important because they help to focus the efforts of military forces on the centre of gravity. However, they assume that before taking action it is possible to fully comprehend a given operational problem; recognise a clear, achievable and static end; and develop a workable sequenced solution. More importantly, both metaphors assume that the context within which a solution is sought is sufficiently stable for the particular end to remain relevant throughout. When addressing complex operational problems, it is not realistic to expect to have the right solution from the outset. The imperative to act means that the solution (including the end-state) will tend to be vague and not fully formed. The Iraq and Afghanistan wars are examples of this phenomenon. The policy aims, campaign objectives and war plans changed throughout the course of both conflicts. The current situations in both wars were not, nor could they have been, anticipated in advance. Therefore, rather than use the term ‘end-state’, Adaptive Campaigning uses the term ‘accepted enduring conditions’, implying that the goal is not a precise and static target.16 Moreover, Adaptive Campaigning recognises that initial action, regardless of how well informed and purposeful it might be, will tend to be a best estimate based on incomplete understanding of a given problem.

The notion that initial actions are only ever a best estimate should come as no surprise to most experienced military professionals. No plan survives first contact with the enemy.17 An implicit tenet of Adaptive Campaigning is that a problem’s initial conditions are less important than the Land Force’s ability to improve its performance over time.18 Therefore, Adaptive Campaigning, specifically the Adaptation Cycle’, assumes that there is no linear path to a desired end, because a system’s complexity will prohibit comprehension without interaction. Brigadier (retd) Justin Kelly and Dr Mike Brennan observe that:

The [Adaptation Cycle] ... accepts that combat is a complex adaptive system. As such it will develop emergent behaviour that cannot be usefully anticipated in advance. Only by iteratively and incrementally stimulating the system can its actual behaviour be at least partially understood and appropriate actions be taken to dampen undesirable emergent behaviours while positively reinforcing desirable ones. Stimulating the system requires that it be provided with energy by taking action. This is not an argument against the need for reconnaissance and planning; rather, it accepts that reconnaissance may provide facts and that planning needs to account for these facts, but that the battle that eventually emerges is entirely unknowable in advance.19

Kelly and Brennan’s interpretation of Adaptive Campaigning has important implications for the form and use made of military plans because it implies that only after interacting with a system will the problem and the desired end fall into focus. Even then, the interaction may cause the problem and therefore the end to change again. Therefore, military plans are largely a common point from which to adjust and the act of planning, which leads to greater common understanding of a problem, is perhaps more important than the plan itself.

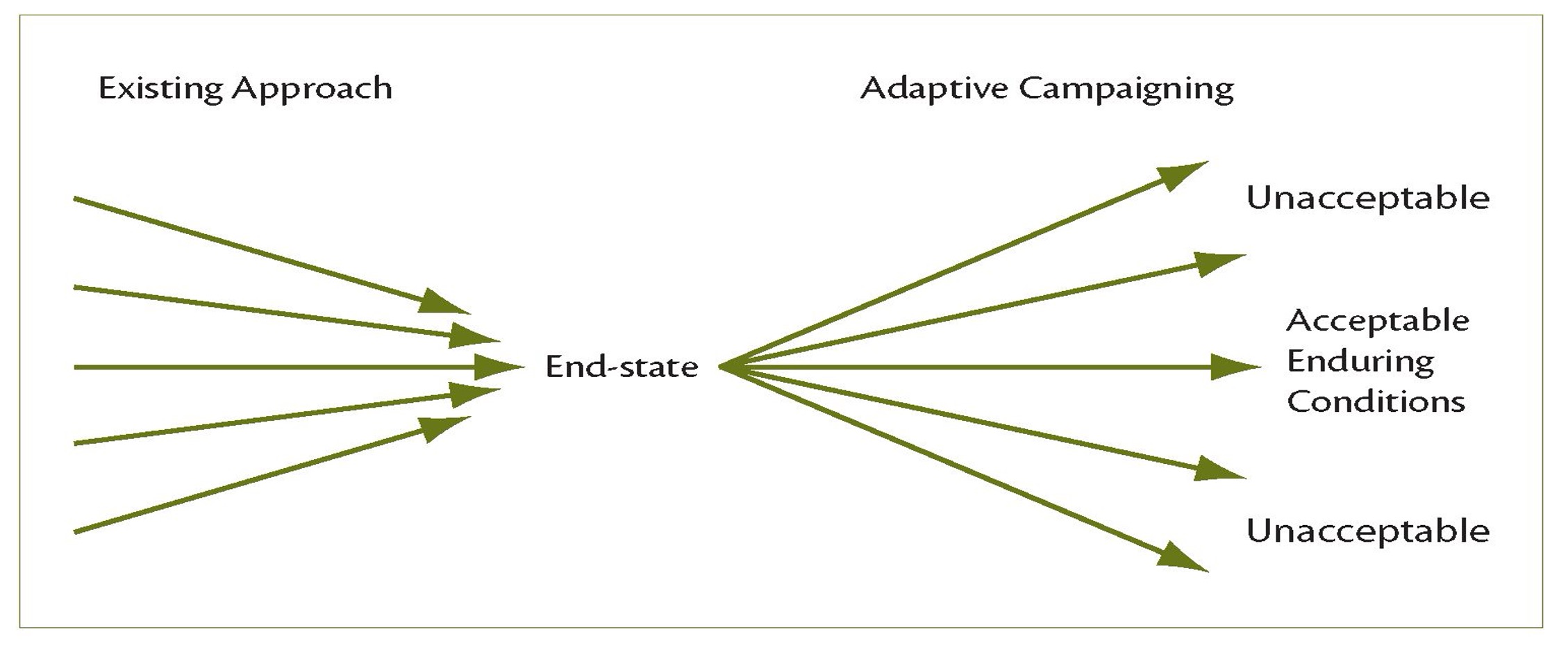

Figure 2 demonstrates the difference between the legacy doctrinal approach and the Adaptive Campaigning approach to planning and executing operations. The existing approach assumes a range of initial conditions and paths that lead to an end state. According to this metaphor, the imperative is to choose the right path, or at some predetermined decision point, shift to another predetermined path. Adaptive Campaigning, on the other hand, assumes that the initial conditions are unimportant and the number of possible ends is many. The implicit imperative is continuous interaction with the dynamic problem to force circumstances toward a vague and shifting end. The latter paradigm takes account of an enemy exercising independent will whereas the former does not.

Figure 2 implies that operational art has a contingent nature. It is a dynamic activity characterised by the application of judgment to fluid problems rather than just a more sophisticated approach to campaign planning and design. Therefore, the imperative of operational art is the pursuit of the right actions in relation to a fluid context. Prussian Chief of the General Staff, Helmuth Von Moltke illustrated the idea as follows:

Strategy is a system of makeshifts. It is more than a science. It is bringing knowledge to bear on practical life, the further elaboration of an original guiding idea under constantly changing circumstances. It is the art of acting under the pressure of the most demanding conditions... That is why general principles, rules derived from them, and systems based on these rules cannot possibly have any value for strategy.20

Developing Land Warfare Doctrine captures, to some extent, the notions that plans are a common point of departure and that operational art has a contingent nature.21 However, these ideas sit uncomfortably with linear metaphors such as ‘end-state’ and ‘lines of operation’ without some clarification of their limited applicability.

This tension has possible implications for officer education and training. The first implication is that greater emphasis should go to post h-hour decision-making rather than pre h-hour decision-making and planning. The second is that an institutional passion for study of the decisions and actions of wartime commanders is imperative. Only through study is the contingent nature of warfare revealed fully. Third, ‘deliberate planning as a means for arriving at a start point’22 is likely to take a different form than traditional planning, which aims at arriving at the complete solution.

The Effects-Based Approach

The contingent nature of operational art poses a direct challenge to the ‘Effects-Based Approach’ to operations. While the Effects-Based Approach is not an explicit part of Land Warfare Doctrine, the Effects-Based Approach underwrites some elements of Land Warfare Doctrine. Examples include the targeting process in the developing counterinsurgency doctrine and some steps in the Military Appreciation Process.23 An Effects-Based Approach is ‘a way of thinking to focus planning activities and the operational conduct on achieving an effect to gain an end state, rather than planning and organising activities.’24 Its conceptual basis is the theory of ‘Effects-Based Operations’, which views military forces as akin to organic systems. The sine qua non of Effects-Based Operations is the paralysis of a military force from the targeting of critical nodes.25 Like Effects-Based Operations, the Effects-Based Approach attempts to link causality from means through mechanism to effect in order to create a general cascading effect on an enemy’s system.

Figure 2. Linear and Non-Linear Approaches to Military Problems

The theory derives from the US Air Force and rests comfortably in the context of applying air power. The rationale is largely to ensure that apportionment and employment of limited assets is relevant and effective. It is an attractive idea and appeals strongly to the desire for stability and control, as well as managerial kinds of thought.26 One of the theory’s flaws is that it assumes an unachievable level of predictability because it overlooks the feedback loops and emergent properties of complex adaptive systems. Another flaw is that it requires an impossible level of knowledge about the enemy and the operating environment in order to know what things to take action against, through what mechanism action will generate the desired effect, and to what extent the effect occurred.27Adaptive Campaigning, on the other hand, assumes that a decisionmaker will have incomplete knowledge of the enemy and the operational environment (the system). This lack of knowledge is a function of the inherent uncertainty of war, but is also a function of the tendency for contemporary adversaries to operate below the Land Force’s detection threshold. Therefore, Adaptive Campaigning seeks to understand, as much as possible, the behaviour of the system through discovery actions rather than a detailed understanding of the system’s parts. Unlike the Effects-Based Approach, which focuses on specific outcomes and their possible cause, Adaptive Campaigning accepts that sometimes it is prudent to act without a clear idea of the effect in mind because action is normally necessary to learn, and leads to the creation or recognition of opportunities. It is, to some extent, a sophisticated version of Napoleon’s approach, ‘One jumps into the fray, then figures out what to do next.’28

The primary influence of the Effects-Based Approach on Land Warfare Doctrine is the targeting process. Developing counterinsurgency doctrine defines targeting as ‘the process whereby operational activity conducted within a [counterinsurgency] campaign plan is focused upon achieving specific effects in support of campaign objectives or tactical actions’.29 Targeting is an attractive process because its prescriptive and reductionist nature generates seemingly purposeful action in a simple and holistic manner. However, targeting assumes that there is some efficacy in considering systems and problems in terms of targets. Constraining thought by such a limiting paradigm in the face of a complex problem is likely to inhibit the range of solutions available to a military force. This paradigm and targeting’s highly structured approach are antithetical to creativity, which is an important function of effective adaptation. Therefore, the Effects-Based Approach (and targeting in particular) is incongruent with Adaptive Campaigning.

Still, the term ‘effect’ is a useful part of the military lexicon. After all, some effects, such as the neutralisation of an enemy battle position with indirect fire, are predictable to a point. The associated concept of targeting is also very effective when the rationale is to best apportion and prioritise the employment of scarce capabilities such as air power and artillery. However, the metaphors are not universally applicable. This lack of sophistication is likely to lead to flawed thinking about complex problems.

Planning And Design

The Army’s doctrinal planning methodology, the Military Appreciation Process, is a proven and highly reliable way of coordinating staff effort to derive adequate military plans in time-constrained environments. However, some of the steps of the Military Appreciation Process lose relevance when there is no single ‘centre of gravity’ (i.e., when a complex problem has no single point of control). For example, The Military Appreciation Process, 2001 states that:

the key activity in [step four of Intelligence Preparation of the Battlespace] is an assessment of the enemy [centre of gravity] and its [critical vulnerabilities] as a basis for subsequent development of the [decisive events]. 30

These decisive events become the framework on which a course of action is built. This step is a good example of the Military Appreciation Process’ linear and methodical approach to problem solving. Its linear approach and its reliance on some of the linear metaphors discussed earlier, make it sub-optimal for solving complex problems.

In recognition of the inadequacies of its own military decision-making process, the US Army has turned to design theory. The US Army’s Military Decision-Making Process (almost identical to the Military Appreciation Process) proved to be inadequate at addressing context (solving the right problem), recognising changes in context (leading to adaptation), and spawning creativity (solving the problem well) in dealing with contemporary conflicts.31 Consequently, in anticipation of its value, the US Army developed a sophisticated design methodology to compliment its Military Decision-Making Process. In an attempt to address similar problems, recent amendments to Land Warfare Doctrine include discussion of operational design. However, Australian Army design doctrine is undeveloped, particularly in light of the US experience. The Australian Army’s undeveloped view of design is a handicap for planners addressing complex operational problems.

Recent doctrinal amendments address operational design in greater depth than ever before. However, the doctrinal approach to operational design is immature. It regards design as the process of problem framing and regards planning as the process of problem solving.32 According to this paradigm, operational design is about analysis and understanding rather than solution or prescription, and sits apart from and occurs prior to planning. In fact,

design is iterative, meaning it does not follow a linear sequence, and it does not terminate just because a solution has been developed ... design is focused on solving problems, and as such requires intervention, not just understanding.33

Therefore, design is an ongoing activity that seeks to understand a problem and prescribe a solution. It is more than simply problem framing. The key difference between design and planning is that design is about solving problems and planning is about organising for action and controlling performance. This difference suggests that Land Warfare Doctrine emphasises organising and controlling action at the expense of developing and prescribing solutions.

While this misunderstanding of the role of design is important, the greater weakness is the lack of any particular methodology for designing. Design, by definition, takes place in all military planning activities, whether explicitly or not. The course of action development stage of the Military Appreciation Process is largely a process of design. However, the efficacy of treating design as an implied activity within planning rather than singling it out for thoughtful consideration is questionable. Without some sort of method, operational design will prove too difficult to teach and will never get anything more than lip service from the officer corps. Therefore, there may be some merit in reviewing the doctrinal decision-making processes with a view to a more sophisticated approach incorporating emerging design methodologies.

The Primary Implications Of Adaptive Campaigning

The tension between Land Warfare Doctrine and Adaptive Campaigning highlights the enduring and irreconcilable tension between two extreme approaches to warfare. One extreme is that practiced by the Germans from around 1870 to 1941. One might describe it as the ‘follow-your-nose’ approach. This approach emphasises flexibility, mission command, command forward, loosely coupled plans, simple orders, few objectives, authority pushed to the lowest levels and rapid exploitation of opportunities. Its weakness is that synchronisation is left largely to chance and its strength is that action tends to be congruent with context. The other extreme approach is the methodical approach epitomised by the French in 1940. This approach emphasises tightly coupled plans, centralised control, synchronisation, timetables, information, prediction and command from the rear. Its weakness is the tendency to fight the plan at the expense of adapting to a changing context; either failing to seize opportunities or following through with a plan well after circumstances made it irrelevant. The strength of the methodical approach is that synchronisation of effects and economy of effort are optimal. Land Warfare Doctrine fails to address the irreconcilable tension between the two extremes. Metaphors from both extremes sit side-by-side with no reference to the tensions that exist between them.

This tension is particularly stark in Adaptive Campaigning because its logic sits more or less in the ‘follow-your-nose’ camp, but the concept also resides within a strategic context that anticipates amphibious operations in a littoral environment. Amphibious operations by their nature require tightly coupled plans, high levels of synchronisation, timetables, centralised control, a heavy reliance on information and command from the rear. They sit at the other end of the spectrum. Moreover, their joint character means that an Effects-Based Approach has some merit. The implication is that Land Warfare Doctrine should reflect the strengths and weaknesses of both logics and articulate the tensions between the two. In particular, it should describe the limited domains of applicability of certain concepts and metaphors. This has important implications for officer education and training.

Conclusion

Adaptive Campaigning has important implications for the way the Army interprets operational problems, thinks about them, develops solutions to solve them and directs forces to execute solutions. Most of these implications are a consequence of the concept’s recognition of the non-linear nature of war. Some important legacy doctrinal metaphors are inconsistent with the logic of Adaptive Campaigning, and existing design and planning methodologies are inadequate for dealing with complex problems. Yet, they maintain some enduring utility. Therefore, Land Warfare Doctrine must reconcile two different logics based in two different approaches to warfare.

Still, clarifying old and new doctrinal concepts will not expunge the ingrained metaphors from the minds of officers trained in their usage. Moreover, the Army does not have a mature methodology for operational design. Therefore, Adaptive Campaigning has immediate implications for officer education and the Army’s doctrine and culture, necessitating a review of the principal Land Warfare Doctrine publications and the officer-training continuum.

There are, therefore, three primary challenges. The first challenge is to bring together Adaptive Campaigning, Land Warfare Doctrine and Joint doctrine, and reconcile the differing logics in one coherent approach. The second challenge is to bring officer training and education into line with the new doctrine. The third and overarching challenge is to implement this change in an organisation that has its own stabilising feedback loops that will frustrate attempts to change it.

About the Author

Lieutenant Colonel Chris Smith is an infantry officer with six years’ regimental service with 2 RAR. His other service includes Adjutant 42 RQR, Field Training Instructor and Adjutant RMC, and a member of the HQ 3 Bde staff. Lieutenant Colonel Smith has seen operational service as a platoon commander in Rwanda, 1995; as an UNMO in Israel and Lebanon, 2002-03; and as the operations officer of Overwatch BattleGroup (West) in Iraq, 2006. He is a recent graduate of the US Army Command and General Staff College and the US Army School of Advanced Military Studies, and holds a Masters of Military Art and Science. Lieutenant Colonel Smith is currently posted to the Directorate of Future Land Warfare and Strategy in Army Headquarters.

Endnotes

1 Adaptive Campaigning: Army’s Future Land Operating Concept, Department of Defence, Canberra, p. 39.

2 Ibid, p. 27.

3 R Gallagher and T Appenzeller, ‘Introduction’, Science, Vol. 284, No. 5711, 1999, p. 79.

4 Peter Fryer, ‘What are Complex Adaptive Systems?’ <http://www.trojanmice.com/articles/complexadaptivesystems.htm>

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 A Kuruc, ‘The Relevance of Chaos Theory to Operations’, Australian Defence Force Journal, No. 162, September/October 2003, p. 5.

8 LWD 1, The Fundamentals of Land Warfare, Department of Defence, 2008, p. 48.

9 Reductionism is an approach to understanding complex things by breaking them down into their component parts and analysing the parts in order to understand the whole. In Carl von Clausewitz, On War, Michael Howard and Peter Paret (trans. and ed.), Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1989, p. 485, Clausewitz made the linear and proportional basis of centre of gravity explicit: ‘The scale of a victory’s sphere of influence depends, of course, on the scale of the victory, and that in turn depends on the size of the defeated force. For this reason, the blow from which the broadest and most favourable repercussions can be expected will be aimed against that area where the greatest concentration of enemy troops can be found.’ The centre of gravity was introduced to military theory by Clausewitz as an analogy to the concept first invented by Archimedes. In mechanics, the centre of gravity is a single point where the behaviour of an object acts as if all its mass were concentrated at this point. Knowing where the centre of gravity is makes predicting the movement and direction of physical objects easier. Clausewitz argued that armies, too, have a centre of gravity at the point of greatest concentration of troops, and that all energy should be expended against this point, because it is the hub of all power and movement.

10 D Dorner, The Logic of Failure: Why Things Go Wrong and What We Can Do to Make Them Right, Metropolitan Books, New York, 1996, pp. 89-90.

11 Ibid, p. 90.

12 Adaptive Campaigning, p. 41.

13 LWD 3-0, Operations (Developing Doctrine), Department of Defence, 2008, p. 26.

14 Ibid, pp. 2-60-2-65.

15 Ibid, p. 2-64. Lines of operation were once literally geographical lines. In their revived form, as used by General Franks in Iraq, lines of operation decompose an operation into functional components. The famous Franks chart is found at <http://herdingcats.typepad.com/my_weblog/2005/08/teams_centers_a.html>. The ubiquity with which lines of operation have been unthinkingly replicated since Franks used this technique is reminiscent of Clausewitz’s discussion of Methodism. It is an oversimplified form of categorisation that hides inter-relationships, interdependencies and nonlinearities. The Adaptive Campaigning variant on lines of operation is much better, because it attempts to emphasise interdependencies. However, the ‘line’ part of the label still retains a misleading metaphor.

16 Douglas O Norman and Michael L Kuras, ‘Engineering Complex Systems’, The MITRE Corporation, January 2004, <http://www.mitre.org/work/tech_papers/tech_papers_04/norman_engineering…;

17 Originally in Helmuth Von Moltke, Militarische Werke, Vol. 2, Part 2, pp. 33-40. Found in Daniel J Hughes (ed), Moltke on the Art of War: Selected Writings, Presidio Press, New York, 1993, p. 45.

18 AM Grisogono and A Ryan, Operationalising Adaptive Campaigning, 12th ICCRTS, Newport, p. 20, <http://www.dodccrp.org/events/12th_ICCRTS/CD/html/papers/198.pdf>

19 J Kelly and M Brennan, Distributed Manoeuvre: 21st Century Offensive Tactics, Land Warfare Studies Centre, Canberra, 2009, p. 26.

20 Dorner, The Logic of Failure, p. 97.

21 LWD 1, p. 52.

22 Ibid.

23 For example, LWD 3-0-1, Counterinsurgency (Developing Doctrine), Department of Defence, 2008 says ‘Targeting is the process whereby operational activity conducted within a COIN campaign plan is focused upon achieving specific effects in support of campaign objectives or tactical actions. It is important to understand that targeting is undertaken in all operations, and not just physical (lethal) attacks against insurgents.’

24 ADDP 3.0, Operations (Provisional), Department of Defence, 2008, p. 2-1. [emphasis added]

25 J Warden, The Air Campaign, National Defense University Press, Washington DC, 1988.

26 Adam Elkus, ‘Report: The End of Effects-Based Operations?’, Rethink Security, 22 August 2008, <http://rethinkingsecurity.typepad.com/rethinkingsecurity/2008/08/report…;

27 General J N Mattis, Commander US Joint Forces Command, in a memorandum for US Joint Forces Command, 28 May 2009.

28 Dorner, The Logic of Failure, pp. 160-61.

29 LWD 3-0-1, p. 7-13.

30 LWD 5-1-4, The Military Appreciation Process, Department of Defence, 2001, p. 3-35.

31 From a brief by Dr Alex Ryan to a US Army School of Advanced Military Studies seminar, 2008.

32 LWD 3, p. 2-4.

33 S Banach and A Ryan, ‘The Art of Design: A Design Methodology’, Military Review, March-April 2009, p. 105.