Abstract

The Australian Army’s success in force generation and preparation and the conduct of contemporary and future operations will be determined largely by its capacity to learn and adapt. Only through a continual cycle of reviewing and adapting in response to a changing environment will the Army retain its ability to fulfil its operational charter while also creating a culture that is capable of encouraging innovation and creativity. The ‘Adaptive Army’ initiative is more than a simple reorganisation. It is a cultural realignment that seeks to generate profound change in training, personnel management, knowledge management, learning cycles and, eventually, the Army’s culture.

The strategic environment in which the Army operates has altered significantly over the last decade. This tumultuous period has been marked by the rise of violent extremism and the consequent need to develop the capabilities to combat this extremism in an extraordinary variety of theatres. This is also a period that has seen the Australian Army operating at a significantly higher tempo in a range of complex environments in vastly differing roles including warfighting, peace support, stabilisation operations and humanitarian assistance in the wake of natural disaster. The Australian Government has demonstrated a willingness to invest more in Australia’s land forces, producing a commensurate increase in the Army’s size and capability. Conversely, the recent financial crisis has highlighted the necessity for the Army to operate in a climate of economic stringency. Precious resources must be utilised effectively and the Army must invest wisely in those future capabilities likely to provide the greatest utility across a broad range of scenarios.

The Army’s response to its changed environment has taken the form of a rigorous self-examination that has lasted the better part of twelve months and produced a strategy now known as the ‘Adaptive Army’ initiative. The last time that the Australian Army undertook such a comprehensive review was in the early 1970s. Then, the Army introduced a system of functional commands which served its purpose well until the early 1990s. However, as the operational tempo increased in the late 1990s, this structure began to show its age. That juxtaposition of an ageing structure and a dynamic operational environment proved the catalyst for the development of the Adaptive Army initiative—an initiative designed to ensure that the generation and preparation of land forces is conducted more effectively and efficiently and is better aligned with the new joint command framework.

The Australian Army has a long history of adapting to enormously varied operational scenarios. Yet, to adapt most effectively—in a systemic manner throughout the entire deployed force—the organisation that builds the force for deployment must be characterised by a culture of adaptation. Logically, it follows that the Army as an institution also must boast such a culture of adaptation, and must be equipped with efficient feedback loops—particularly to aid lesson retention—so as to adapt readily to operational demand. I am convinced that such a culture of adaptation will see the Army best placed to meet the contemporary and future security challenges that are its core business.

The Adaptive Army initiative has been extensively wargamed and modelled and has proven its worth as a vehicle for the evolution of the Australian Army into a more effective and agile army. The Adaptive Army initiative is more than a simple reorganisation. It is a series of inter-linked initiatives, bound together through common intent, to ensure that the Army remains relevant and effective and that it maintains its reputation as one of the nation’s most respected institutions. It encompasses personnel initiatives, materiel management improvements, advances in training and education, advances in knowledge management, better equipment and new doctrine. The Adaptive Army initiative, its character, its aims and the profound change it promises are explained in detail in this article.

What Is the Adaptive Army Initiative?

The Adaptive Army initiative is the most significant restructuring of the Australian Army since the implementation of the Hassett reforms in 1973. The former system of functional commands reflected the assumptions of an earlier era when the single services of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) tended to collaborate more effectively with their allied counterparts than with other elements of the ADF. Not until the era of defence self-reliance did the ADF develop a truly joint mindset. In today’s climate the Army never operates alone and its structures must reflect this simple truism while also providing institutional agility and adaptability.

The most visible and immediate change under the Adaptive Army initiative is the replacement of the existing system of functional commands with a new command and control structure based on different temporal learning cycles. The new Army structure comprises a reorganised Army Headquarters (AHQ) and three subordinate functional commands:

• Forces Command (FORCOMD) is principally concerned with force generation, utilising a single training continuum that unifies the majority of the Army’s conventional individual and collective training. Its primary learning focus is the medium learning loop and doctrine development.

• Special Operations Command (SOCOMD) is a short learning loop organisation. It retains its extant mission and functions which include the responsibility to prepare, conduct mission rehearsal exercises and certify force elements for deployment on operations.

• Headquarters 1st Division (HQ 1 DIV) is primarily concerned with force preparation, conducting higher level collective training for directed missions and contingencies. Its principal learning focus is the short learning loop and the development of tactics, techniques and procedures for contemporary operations.

However, the Adaptive Army initiative is more than just a reorganisation. It aims to change the Army’s cultural mindset and the way it operates. The Adaptive Army initiative is a cultural realignment designed to inculcate an institutional culture of adaptation at all levels of the Army. This will generate profound change in training, personnel management, knowledge management, learning cycles and, eventually, the Army’s culture. To this end, the Adaptive Army initiative aims to make the Army a more effective organisation by:

• improving the Army’s alignment with, and capacity to influence, the ADF’s strategic and operational joint planning

• improving force generation and preparation while balancing operational commitments and contingency planning

• increasing the effectiveness and efficiency of training within the Army

• improving the linkage between resource inputs and collective training outputs within the Army’s force generation and preparation continuum

• improving the quality and timeliness of information flows throughout the Army so as to enhance its adaptation mechanisms at all levels

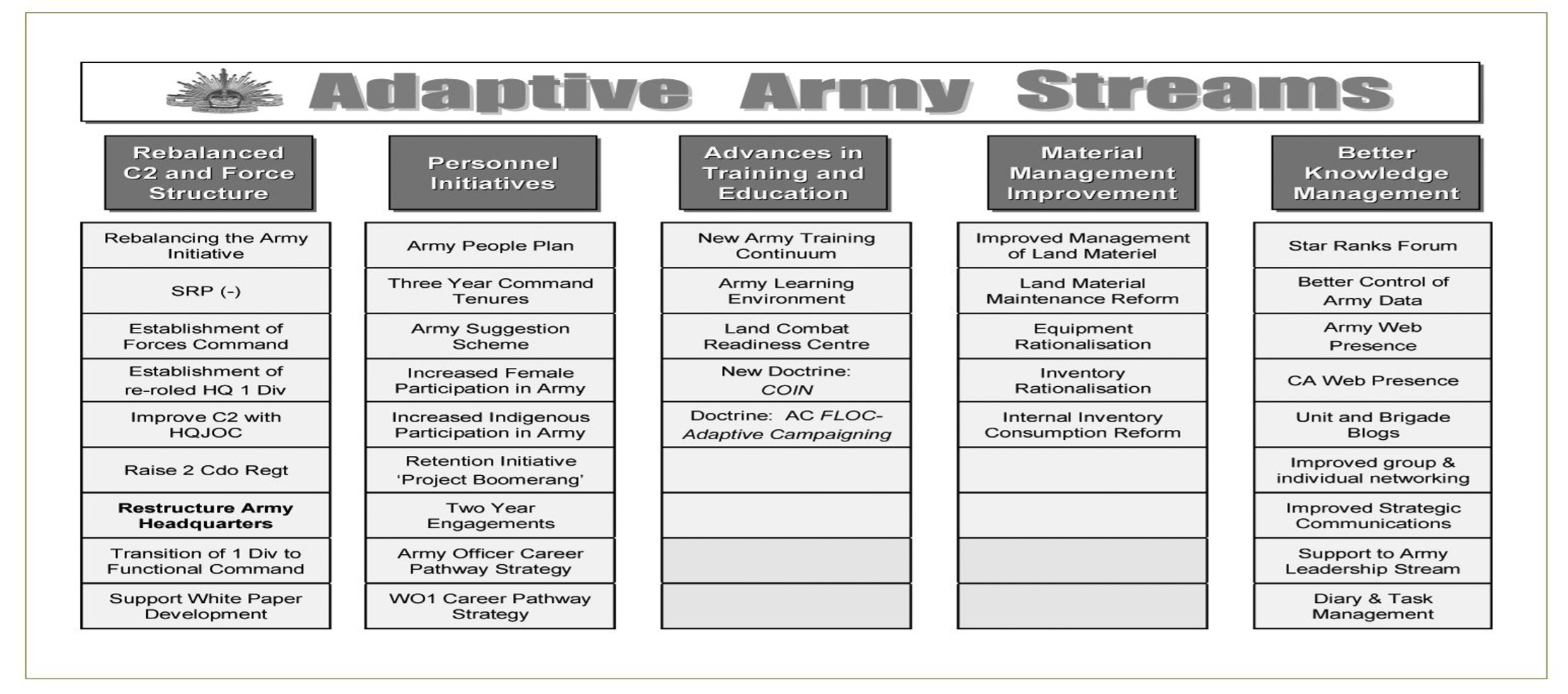

The Adaptive Army initiative is an inter-linked series of measures designed to realise these goals and which boasts a number of key elements as illustrated in the diagram below.

Rebalanced C2 And Army Structure

The most distinctive feature of the Adaptive Army initiative is the creation of an organisation and structure linked to different temporal adaptation cycles within the Army. The effectiveness of the new structure will be contingent on the rapid establishment of a seamless and highly evolved force generation (FORCOMD) and force preparation relationship (1 DIV) between the new commands. These commands will, in turn, establish a relationship with Headquarters Joint Operations Command (HQJOC) for the conduct of operational planning. AHQ will retain responsibility for the provision of advice on the sustainability of specific Army capabilities.

Figure 1. Adaptive Army Streams

These new arrangements will align the Army far more closely with extant ADF joint command arrangements, while facilitating the maintenance of foundation warfighting skills throughout the Army and the acquisition of mission-specific skills as required. All of these skills can now be clearly articulated and calibrated against commonly agreed measures. The degree of synchronisation between individual and collective training that can be achieved under this system is quite simply unprecedented.

Under the Adaptive Army initiative, AHQ has been restructured and now comprises two discrete divisions. The Deputy Chief of Army (DCA) Division oversees the Army’s day-to-day business, looking ahead approximately eighteen months. The new Head Modernisation and Strategic Planning Division supervises the development of new capability and the introduction and integration of funded new capability.

FORCOMD, the newest—and largest—functional command, was raised on 1 July 2009. Training in FORCOMD will focus on generating forces that are competent in foundation warfighting skills. High-level warfighting training is the crucible that develops highly competent and professional leaders capable of functioning effectively under extraordinary pressure. This training also provides the best environment for the development of adaptation mechanisms at all levels. As such, warfighting skills are the essential foundation for all types of operations.

The fusion of existing organisations into FORCOMD will—for the first time— provide the Army with a single synchronised and integrated Army Training Continuum with objective assessment of individuals and force elements against clearly articulated standards endorsed by the Chief of Army. As a result, the process of force generation and preparation both for operations and less immediate contingencies will become far more coherent.

1 DIV’s key responsibility is force preparation—the training of conventional Army force elements in preparation for operations based on the requirements of Commander Joint Operations (CJOPS). This training will be supported by force preparation activities conducted by FORCOMD. These activities will focus on concentration, mission-specific training, mission rehearsal exercises, certification and post-operation demounting activities for deployed force elements. Like SOCOMD, 1 DIV is aligned to the shortest adaptation cycle and incorporates lessons from deployed forces into the preparation of those force elements that will immediately follow the deployed forces into an area of operations.

HQ 1 DIV will retain its capacity to deploy as a two-star joint headquarters and will work closely with CJOPS in the conduct of operational planning. COMD 1 DIV will be responsible for mounting all conventional operations conducted by Army force elements (less SOCOMD force elements) and will ensure their certification prior to deployment.

HQ 1 DIV will exercise technical control of all deployed Army force elements on behalf of the Chief of Army. This includes responsibility for the lessons learned cycle from those forces assigned to SOCOMD and other elements of the deployed or supporting force. This process is designed to facilitate the rapid feedback of lessons into the Army’s learning cycles and to ensure the appropriate employment of deployed forces. HQ 1 DIV will also act as the re-entry point for force elements redeploying from operations.

One significant feature of the Adaptive Army initiative is the new Land Combat Readiness Command (LCRC), which was raised in December 2008. LCRC’s role is to provide practised, ready and certified forces for specific operations and contingencies, as directed by CJOPS, to ensure the successful conduct of joint, combined and inter-agency operations. LCRC also conducts warfighting training to support the achievement of the Army’s mission essential task requirements. LCRC supports COMD 1 DIV by coordinating higher level training and assessment so as to raise training standards across the Army. The mounting, assessment, certification and demounting of force elements will be standardised within this new organisation so as to maximise the Army’s success on current and future operations.

The Special Operations Commander Australia (SOCAUST) retains his higher command relationships with the Chief of the Defence Force, Chief of Army and CJOPS. SOCOMD has allocated tactical command to CJOPS for special operations planning and conduct of campaigns, operations, joint and combined exercises and other directed activities. For domestic counter-terrorist and other sensitive strategic operations, SOCAUST maintains a direct relationship with the Chief of the Defence Force.

SOCOMD retains its responsibility to the Chief of Army for the force generation and force preparation of units assigned to CJOPS for the provision of a scalable headquarters with the flexibility to tailor size to operational requirement. SOCOMD will also ensure that its development of collective training standards and assessment against those standards aligns with the processes to be developed by FORCOMD.

One of the key drivers in the evolution of the Army’s higher command links is the need to align these with changes in the ADF’s joint operational command and control structures. The Chief of Army will continue to provide strategic planning advice to CJOPS; however, COMD 1 DIV will exercise technical control over assigned Army conventional force elements and remain under operational control of HQJOC for planning purposes.

Personnel Initiatives

Fundamental to the success of the Adaptive Army initiative is the Army’s ability to recruit, train, develop and retain high quality officers, soldiers and public servants. The Army’s people must be better educated, better equipped to understand, embrace, lead, and exploit the opportunities offered by this complex environment. Significantly, the Army must ensure that its people are inculcated with a culture that fosters and encourages a flexible approach to solving complex problems.

The Army People Plan was released in May 2009 and complements the implementation of all elements of the Adaptive Army initiative by providing a workforce that is appropriately trained and educated—and the right size. The Army People Plan encompasses six strategic personnel themes, and all Army personnel initiatives will be reviewed and aligned with these themes, including those designed to enhance retention and to improve career management to provide the capacity and flexibility to support the Adaptive Army initiative.

In the past six months the Army has developed a series of strategies known as the ‘Army career pathways’ which include the Army Senior Officer Career Pathway Strategy and the Army Officer Career Pathway Strategy. An Army Warrant Officer Career Pathway Strategy is also in the final stages of refinement. A three-year command directive has been introduced and innovative policies designed to improve retention are currently under development.

A comprehensive strategy for the career progression and development of officers is essential to provide maximum opportunity for these people to excel and achieve career aspirations. With a sustained high operational tempo, officers are required to respond to a wider range of command, leadership and management demands in a variety of challenging and dynamic environments. Ultimately, it is the ability to adapt to these operational demands that will ensure the long-term development, relevance and vitality of the officer corps and, in turn, of the Army.

For officers in particular, the paradigm of an Army career based on passing through ‘gates’ such as Staff College and sub-unit or unit command, does not boast the flexibility required under the Adaptive Army initiative. While development and command appointments remain an important part of the fabric of the Army, they can no longer constitute the sole means to ensure career progression. What is required is an enhanced career management paradigm with the agility to provide flexible career pathways that are not restricted to the traditional ‘gates’.

The Army’s career pathway strategies are based on a culture of positive career relationships and performance management, enhanced career development opportunities, and flexible career pathways. Ultimately these career pathway strategies will contribute significantly to creating leaders with the intellectual capacity to perform a diverse range of activities in an increasingly complex environment—and the ability to adapt effortlessly to dynamic and challenging scenarios.

The Australian Army will transition to three-year command tenures for unit command and formation command from January 2010, with two-year commands restricted to exceptional circumstances. This change in tenure also extends to all Regular and Reserve command appointments. This initiative will reduce the high formation and unit tempo that results from compressed training regimes and will also provide increased opportunity for commanders to consolidate their leadership and management skills. At the same time the change in length of tenure will ensure the continuity for a single command team to manage a full deployment cycle within a unit or formation, including pre-deployment, deployment and reconstitution.

The Army is currently exploring retention initiatives which are designed to increase individual periods of service by addressing the extrinsic and intrinsic expectations of its people, and through the effective use of all the available elements of the workforce. The recent Defence policy that extends retirement age to sixty, for example, provides tangible recognition of the fact that the Army cannot afford to lose valuable corporate knowledge five to eight years earlier than is necessary. Similarly, the Army recognises the need to space career milestones to allow such events as parental leave and civil schooling to occur between each promotion gate without detriment to the individual.

Enhanced Training And Education

The Army’s principal role is the organising, training and equipping of forces for operations and military contingencies. To achieve this, it must be able to plan and conduct effective individual and collective training. This training must be focused, progressive and simple. The Army’s foundation warfighting skills form the elementary building blocks for the maintenance of high end warfighting skills.

Foundation warfighting training is the fundamental individual and collective training that underpins operational capability. This is the bedrock from which the Army adapts to meet its operational requirements and which equips force elements to conduct the full spectrum of sustained operations. Training levels and standards are the means to assess the Army’s training. Under the Adaptive Army initiative, this foundation warfighting capability will be delivered through the newly developed Army Training Continuum.

The Army Training Continuum commences with ab initio training and progresses through individual and collective training and force preparation to produce force elements that can conduct operations successfully. Training encompasses a combination of tasks performed to a standard, level, condition and frequency comprising individual and collective training. Significantly, the continuum will be overseen by a single command, thus ensuring that a unified approach to the conduct and assessment of training is implemented across the Army. The new Army Training Continuum was endorsed at the Chief of Army Senior Advisory Committee in June 2009 and was implemented on 1 July 2009 with the raising of FORCOMD.

Under the Adaptive Army initiative, the Australian Army aspires to be a true learning organisation in which shared, timely knowledge and flexible learning are accepted as the norm for individuals, teams and the organisation. The Army Learning Environment provides the framework within which this culture of adaptation will flourish, with learning viewed as an ongoing activity that occurs formally and informally at all levels of the organisation. The Army Learning Environment will be delivered through the Army Continuous Learning Process, which is structured along three lines of development: training and education, lessons integration, and the creation of an environment conducive to learning. This integrated Army Learning Environment will have been achieved when the Army boasts an environment characterised by the optimal conditions for learning and when the Army routinely converts lessons into learning in a relevant, effective and efficient manner.

Adaptive Campaigning – Future Land Operating Concept has recently been endorsed as the Army’s new capstone document. This document builds on the Army’s previous conceptual documents— Complex Warfighting (2004) and Adaptive Campaigning (2006)—and is guided by the Adaptive Army initiative and the 2009 Defence White Paper. Adaptive Campaigning provides the conceptual and philosophical framework and force modernisation guidance for the Army to adapt to the complex challenges of future conflict. This document incorporates recent operational lessons and insights, current DSTO research, worldwide trends, and domestic and international developments. Most importantly, it describes the actions of an integrated joint land force within a broader joint, whole-of-government and inter-agency approach to the demands of complex war.

As well as providing force modernisation guidance, Adaptive Campaigning will be transitioned rapidly and systematically into doctrine, beginning with an update of the Army’s counterinsurgency and peace support doctrine, both scheduled for re-release in 2009. To expedite the incorporation of enduring lessons into doctrine and training, the Army has devolved doctrine sponsorship to the respective training authorities, thereby allowing sponsor-endorsed lessons to be simultaneously incorporated into both doctrine and training.

Materiel Management

The Adaptive Army initiative foreshadows a change to the way that the Army views the ownership and use of land materiel. For some time, too much of the Army’s equipment has been spread too thinly across the organisation and across maintenance systems that are not optimised to meet individual, collective and mission-specific training requirements. The Adaptive Army initiative now provides the necessary impetus to address equipment holdings in units versus loan and training pools, the inventory required to sustain existing capability and the maintenance system itself as one integrated materiel management system.

The Adaptive Army initiative will lead to the rationalisation of equipment within units to establish reliable loan and training pools—although greater use of loan and training pools to satisfy equipment utilisation priorities also harbours its own challenges including, for example, the lower level of operator maintenance that is traditionally experienced with loan equipment. The Army will also need to be far more deliberate in planning for the use of this equipment in training, resisting the urge to change training activities constantly with the consequent flow-on effects to other planned activities. To maximise flexibility in line with the Adaptive Army initiative, appropriately sized pools with set priorities that allow access to materiel as required must become the norm. Gaining support from enabling groups to assist in the holding and management of these pools on Army’s behalf will also constitute a challenge.

Currently, the Army is working closely with the Defence Materiel Organisation (DMO)—the capability manager which manages all land materiel on behalf of the Chief of Army. Some of the materiel management reforms already underway in this area include a review of the inventory managed by DMO, a review of the performance measures and reporting under the Materiel Sustainment Agreements, a review of preventative maintenance regimes, and a repair pool trial for B vehicles. The review of the DMO inventory is aimed at optimising holdings against classifications that support the equipment life of type for both training and operational contingencies.

Within the Army itself, the manner in which materiel is consumed is also being reviewed in an effort to reduce the cost of ownership and allow reinvestment of funds to higher priority areas. The first tranche of this reform has commenced with changes to the way the Army holds, issues and consumes combat clothing and personal field equipment. Simply put, the Army’s consumable inventory is too large, increasing the governance burden within units and tying up resources that could be employed more profitably elsewhere.

In conjunction with DMO—and Joint Logistic Command which is responsible for the conduct of base repair—the Army is seeking to increase the maintenance capacity within units while, at the same time, reducing the maintenance burden. Supporting efforts to achieve this include the B vehicle repair pool trial, the review of preventative maintenance regimes, the renegotiation of supporting maintenance contracts, and a revised maintenance agenda to be implemented across the entire land materiel maintenance system. Because of the complexity of this system, tight coordination between the relevant groups is essential to ensure the increased operational availability of land materiel.

More efficient materiel management processes are being developed so as to reduce the cost of ownership and reinvest the savings in personnel and funds. The availability of land materiel will be increased through the reduction in unit equipment holdings and an expansion in the capacity of the maintenance system from unit level to the national support base. Initial guidance has been issued on improving inventory management within the Army and reducing the cost of ownership (CA Directive 20/08).

Army Knowledge Management

While the Adaptive Army initiative acknowledges that the Army’s hierarchical structure remains crucial to its culture, it also highlights the fact that current and evolving technologies, appropriately identified, harnessed, applied and exploited, have the potential to empower both individuals and the chain of command. At its heart, adaptation balances the need to change as the situation evolves with a requirement to retain important corporate knowledge. What is difficult, however, is to ascertain what precisely must be retained from a corporate knowledge perspective. Achieving institutional agreement on this fine balance is apt to be more difficult still.

Knowledge management within the Army, as in many other large national and global organisations, is yet to be truly optimised. While the Army retains its institutional reputation for agility, responsiveness and reliability across an increasingly complex, ambiguous and diffuse operating environment, much of this strength is contingent on the quality of the Army’s people and longstanding training regimes, as opposed to other less clearly definable essentials such as the management of knowledge.

In future, the enduring strengths of the Army must be enhanced by an equally agile, reliable and responsive system for knowledge management, for the longer term and mutual benefit of both commanders and soldiers. The optimal confluence of these three pillars—people, training and knowledge management—will contribute significantly to the realisation of a truly adaptable army for the twenty-first century.

The Adaptive Army initiative recognises both the significance of the Army’s hierarchical structures and the imperative for technology to augment and complement these in the future. The Army’s approach to knowledge management is to view it as of enduring importance. Implementation of an optimised and flexible management regime aligned to existing and relevant Army structures, processes and corporate knowledge will empower all the Army’s people wherever they are placed in the chain of command.

Conclusion

The Adaptive Army initiative is founded on the Army’s hard-won lessons over the last decade—lessons on operations, force generation, joint interaction and the process of adaptation. At the same time, the implementation of the Adaptive Army initiative is itself a learning process. As lessons are learned during implementation, the Army will adjust and adapt based on those lessons. This will require leaders at all levels to work towards the common goals described in this article, while also exercising and fostering initiative and innovation in their soldiers.

While much remains to be done, significant progress has been made in the five streams of the Adaptive Army initiative since August 2008. The Army has conducted a stringent internal process including war games, seminars and back-briefs to support the implementation of the Chief of Army’s directive. Although the Adaptive Army initiative was not dependent on the Defence White Paper, its implementation is closely aligned so as to equip the government to make cost-effective decisions on military capabilities. Ultimately, however, the success or failure of this initiative rests with the operational requirements of the ADF:

Adaptive Army will be successful if it aligns the outputs of Army’s force planning, force generation and force preparation with the joint strategic and operational requirements of the ADF, efficiently and effectively.

This is a worthy aspiration, and one that will require significant progress in each of the five streams of the Adaptive Army initiative over the next twelve months.

Inefficiencies and unnecessary duplication of effort will only be removed through vigorous action.

The Adaptive Army initiative is a fundamental change to the structure of the Australian Army and the way it conducts its core business. It aims to better organise force elements to deal with the ADF’s evolved command and control structures, more efficiently conduct force generation and preparation, and simultaneously master the different learning loops that enhance the Army’s capacity to adapt.

The last decade has challenged the Army’s conduct of its core role—the raising, training and sustainment of land forces for operations. In meeting the challenge on each occasion, valuable lessons have been learned that can be exploited to generate and prepare land forces more effectively for future operations. The implementation of the new command structures, supported by the Army Training Continuum, provides a foundation for subsequent activities to enhance force generation and preparation.

At the end of the day, I seek to inculcate a culture of adaptation within the Army. While as individuals we possess a remarkable ability to adapt, in an institutional sense, the Army does not. The cultural issues inherent in such a dramatic change cannot be managed by simply drawing a new organisational chart—these issues will only be managed through determined leadership and advocacy by leaders at all levels. The Army needs to be agile in its approach to operations, and ready to adapt to a changing world—significantly, this is also the means to create a culture that encourages innovation and creativity.

The Adaptive Army initiative will ensure that the Army is better positioned to contribute to the conduct of joint operations in a manner that balances extant commitments with preparations for future contingencies. Quite simply, the Adaptive Army initiative will result in a more effective Army, and one that is well positioned to transition to the Army After Next in the coming decades.