Abstract

This article operationalises the concept of strategic risk as originally developed by Lykke as an imbalance between ends, ways and means. It explains how non-congruence between any pair of these elements can produce strategic or operational risk. The author develops the new concepts of aspirational, design and menu risk to illustrate how planning risk occurs. Various historical examples demonstrate how these risks can be identified and what techniques are available for their mitigation. The author also develops the complementary concepts of strategic wobble and strategic collapse to allow assessment of what constitutes an acceptable level of risk.

There is no ‘perfect’ strategic decision. One always has to pay a price. One always has to balance conflicting objectives, conflicting opinions and conflicting priorities. The best strategic decision is only an approximation—and a risk.

- Peter Drucker1

Introduction

Risk underlies the security strategies of all nations. Indeed, according to economic and business analyst Peter Bernstein, risk defines the boundary between the ancient and modern worlds since it introduces ‘the notion that the future is more than the whim of the gods and that men and women are not passive before nature’.2 Thus it is surprising that the concept of risk in national security strategy—originally described by Army War College strategist retired Colonel Arthur Lykke—remains imperfectly developed. Strategic risk is the focus of this article which expands Lykke’s original concept and applies strategic risk to operations, providing guidance for modern planners attempting to design future theatre security strategies.

Lykke introduces his concept of strategic risk through a metaphor that characterises strategy as a stool simultaneously balancing ends, ways and means. Within this metaphor, strategic risk is a consequence of any imbalance among the legs of the stool:

If military resources are not compatible with strategic concepts or commitments and/or are not matched by military capabilities, we may be in trouble. The angle of tilt represents risk ... To ensure national security the three legs of military strategy must not only exist, they must be balanced.3

Beyond this definition, Lykke offers the theatre planner no clear guidance on how to identify, measure or mitigate strategic risk. This article addresses those limitations by arguing that Lykke’s model of strategy as a balance of ends, ways and means implies three distinct kinds of risk that will affect the likelihood of success for any theatre security strategy. These three types of strategic risk—aspirational, design and menu risk—possess unique characteristics and offer specific challenges to operational planners. A discussion of their impact on theatre-level planning, how they can be measured and, ultimately, mitigated serves as the central focus of this analysis.

The Decomposition of Risk

According to Lykke, risk occurs when there is an imbalance among the ends, ways and means of strategy. Strategic risk results when any two of these three strategic elements are mismatched. The three distinct imbalances that are possible can be represented as an equation with strategic risk expressed as Θ —the sum of the possible imbalances:4

where E = the ends of a specific strategy

W = the ways of a specific strategy, and

M = the means of a specific strategy.

The first term to the right of the equality sign is the component of strategic risk attributable to an imbalance between ends and means. This risk is referred to as ‘aspirational risk’ since it reflects the mismatch between the ends to which the combatant commander aspires and the resources available to achieve those ends. The second term expresses the imbalance that may exist between ends and ways. If the operational planner selects a way that is inconsistent with the desired ends, then strategic implementation is poorly designed and creates risk, referred to as ‘design risk’. The final term captures the strategic uncertainty that arises from an imbalance between the selected way and the available means. This is known as ‘menu risk’ since it occurs when the operational planner chooses a selection from the menu of ways that is more costly than can be supported by the available means.

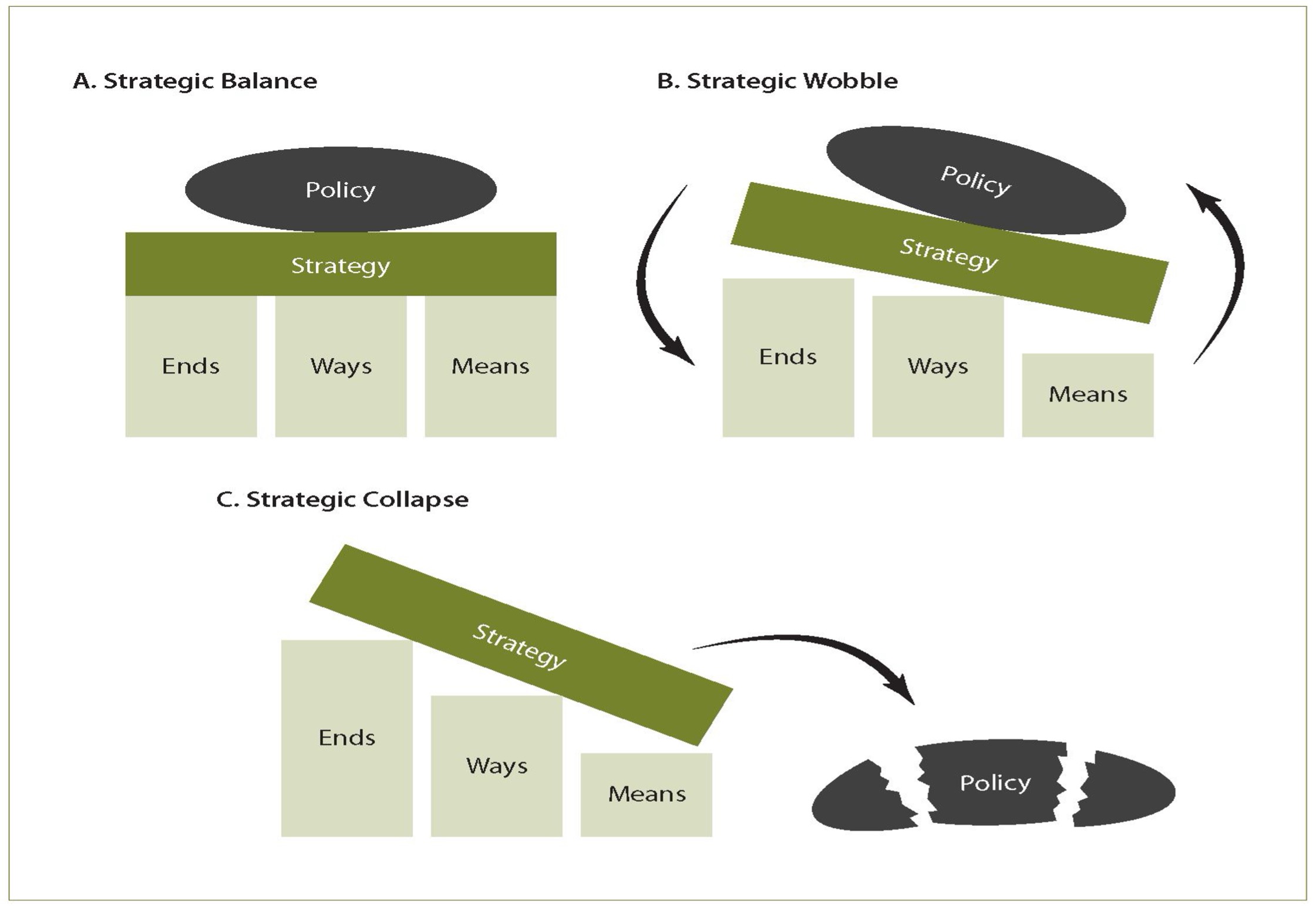

Figure 1 presents a graphic illustration of the effect of ends, ways and means on strategy and, ultimately, policy. In panel A, theatre strategy is balanced—its ends, ways, and means are all aligned. Policy is likewise balanced and rests on a strategy in equilibrium. In panel B, ‘strategic wobble’ occurs as an imbalance emerges among ends, ways and means. This ‘wobble’ may result from an imbalance among all three components of strategy or between any two of those components. At this point, the imbalance is not fatal to strategy, although it does cause strategic oscillation and policy shift. In panel C, the imbalance among the ends, ways and means becomes so severe that the theatre strategy collapses, with consequent adverse policy implications.

The remainder of this article examines the specific kinds of imbalances that can occur among ends, ways and means and describes how the operational planner can measure and manage the resultant risks. The insights provided by this analysis will allow the operational planner to identify and measure these risks which are inherent in all strategy. Such an exercise will also guide the planner in selecting those mitigation techniques that can best prevent policy failure by maintaining either a strategic balance or, at worst case, ‘wobble’.

Aspirational Risk

Aspirational risk represents strategic risk that results from a mismatch between ends and means. Aspirational risk reflects the limiting factor of resources in the achievement of strategic ends. Because this is the most common risk faced by planners, it will be developed in greater detail in this article, with particular attention paid to its ‘bi-directional’ nature, which implies that means might exceed ends or ends might exceed means.

Figure 1. The balancing of ends, ways, and means and the emergence of strategic risk.

Type I Aspirational Risk: Over-Reach

Imbalance between strategic ends and means can also occur when the operational planner over-reaches and the ends exceed the availability of means to support them—referred to as ‘type I aspirational risk’. Operation BARBAROSSA, Hitler’s invasion of the USSR, suffered from this type of aspirational risk. Similarly, Britain experienced this over-reach risk during its Falkland Islands campaign in 1982. Over-reach risk is closely related to the theory of ‘imperial overstretch’ developed by British historian and author Paul Kennedy who postulates that the strategic commitments and interests of a nation exceed its ability to defend them:

If a state overextends itself strategically by, say, the conquest of extensive territories or the waging of costly wars—it runs the risk that potential benefits from external expansion may be outweighed by the great expense of it all.5

Yale political scientist Jeffrey Taliaferro analysed Japan’s attack on the United States in 1941 and described the strategic thinking leading to that decision in terms consistent with aspirational over-reach risk. During the 1930s, Japan sought to create ‘a continental empire that would make Japan economically self-sufficient, and thereby, secure’.6 Such a strategy involved a southward advance by Japan into French Indochina and the Dutch East Indies to acquire raw materials which was bound to provoke conflict with the United States and Britain. Yet Japan persisted, despite the fact that, as Taliaferro writes, the Japanese realised they ‘could not win a prolonged war and that any war had a high probability of lasting several years’.7

Type II Aspirational Risk: Under-Reach

A less common case of aspirational risk occurs when means exceed ends— referred to as ‘type II aspirational risk’. This risk is rare because an excess of resources relative to a particular mission is an unusual state of affairs given eroding defence budgets and increasingly large government deficits. Strategic under-reach allows the operational planner to achieve less than is possible given the means available—a strategic circumstance described by the French general and strategist Andre Beaufre as ‘ends moderate, means large’.8 Beaufre uses the US Cold War nuclear deterrence strategy to illustrate this type of risk. The end selected for this strategy was very basic and limited to the survival of the United States as an independent nation. The means available to achieve such an end, however, were abundant. More recent examples of underreach in which modest ends were combined with abundant means include Operation URGENT FURY (Grenada 1983) and Operation JUST CAUSE (Panama 1989).

When means exceed ends, there is a danger that ends will expand to consume the available means. An expansion in strategic ends that is a consequence of abundant means rather than a product of careful strategy formulation is known as ‘mission creep’. Defence analyst Adam Siegel notes that mission creep can generate risk to strategy by causing a loss of focus, entanglement, and the misuse of assets, particularly military capabilities. His concept of ‘mission shift’ is closely aligned to this article’s description of mission creep as unplanned growth in strategic ends:

Mission shift occurs when forces adopt tasks not initially included that, in turn, lead to mission expansion. There is a disconnect between on-the-scene decisions to involve forces in additional tasks and political decision-making about objectives.9

Measuring Aspirational Risk

The mission analysis step of deliberate planning requires the planner to analyse the assigned task and determine the military objective (end) and to identify resources available (means) for use in developing the plan. It is at this point that planners must make an initial assessment of the magnitude of aspirational risk.

Planners begin their estimate of aspirational risk by screening the assigned task and evaluating the possible resources against a set of risk factors. These risk factors represent a range of different actions that can affect the requirement for resources or identify new resources available to support the operation. There are a number of actions available to the planner to reduce the need for resources and thereby achieve a more equitable balance between means and ends. For instance, it may be possible to scale back the desired objectives, thus contracting the ends towards the available means. Similarly, the planner may be able to increase the time available to achieve the desired objectives or prioritise and phase-in the objectives over an expanded duration. It may also be possible for a subset of the objectives to be delayed, reducing the total resources required.

Alternatively, the planner could seek to increase the resources available to achieve the objectives. Resources may be reallocated from other programs or borrowed from allies or coalition members to support the operation. There may be an opportunity to recruit new allies and gain additional resources. In some cases, emergency or reserve inventories could be diverted to support this operation.

The planner then needs to assess each of these risk factors as likely, uncertain or unlikely, associating each risk factor assessment with a specific point value. If a factor is viewed as likely then it is either associated with a reduction in the resources required or an increase in resources available. In either case, the gap between means and ends narrows, reducing aspirational risk. Thus, those risk factors evaluated as likely are assigned a value of 1. Factors viewed as unlikely imply an increase in resources required or fewer resources made available. Either situation results in an expanding gap between means and ends, and thus greater aspirational risk. Consequently, these factors are assigned a value of –1. Factors which are uncertain are assigned a value of 0 since it is unclear whether they increase or decrease the amount of aspirational risk present.

A qualitative assessment of the aspirational risk present in a specific operation can be achieved through a series of consecutive steps. First, the scores of the individual risk factors are summed before this aggregate factor score is compared to its range of possible values and a set of qualitative risk assessments. Consider the following example in which there are ten factors that the planner identifies as relevant. The range of the aggregate score extends from –10 when all the factors are unlikely, to a maximum value of 10 when all the factors are likely. If the aggregate score is between 10 and 7, then the risk is almost non-existent. The risk is assessed as low if the aggregate score is between 3 and 6, moderate for scores between 2 and –2, high with scores in the –3 to –6 range, and dangerous for scores from –7 to –10. This approach allows the planner to summarise the amount of aspirational risk that is present in any given course of action through a careful identification and evaluation of the factors governing the difference between means and ends. This assessment will permit the planner to more accurately evaluate the risks to mission success and will assist in the design of a more effective course of action.

Mitigating Aspirational Risk

There are many ways to mitigate aspirational risk. Principal among these is the adjustment of the ends so that they are consistent with the available resources. Most commonly, this will involve scaling back the ends so that the resource constraints become less binding. This method was applied during the 1973 Paris Peace Accords between the United States and North Vietnam, which resulted in a less comprehensive settlement than that initially sought by the United States.

Another way to adjust strategic ends so as to mitigate aspirational risk involves pursuing the objective over an extended time interval thus requiring a less intensive use of resources, as exemplified by the Cold War between the United States and the USSR. An objective can be delayed, thereby eliminating the need for a set of resources. Hitler’s decision to defer Operation SEA LION, the German invasion of Britain, released aircraft and troops for use in Russia and the Balkans. The planner can also mitigate risk through the prioritisation of objectives and a scheduled phase-in as illustrated in the US Pacific island campaign during the Second World War.

Modifying the means will also reduce aspirational risk. This will usually require the operational planner to identify additional resources. Increasing resources available to the planner is the most direct way to accomplish this; resource levels can be boosted also by borrowing from other programs, reallocating or running a deficit—all methods that have been used to find resources to support Operation IRAQI FREEDOM. The recruitment of new allies or coalition partners (which occurred during the first Gulf War and, more recently, during the Global War on Terror) is another method of enhancing the strategic means. Planners can also direct resources to deploy in phases in a ‘pay as you go’ approach. The US Cold War strategy reflected this approach as new weapons systems were developed and deployed over several decades. In more extreme cases, resources can be obtained by consuming seed capital, a last resort employed by the Japanese government during the Second World War. Finally, resources can be obtained from the objective itself in a ‘live off the land’ approach. In this case, the force becomes self-sufficient, creating its own resources, the approach adopted by the German Army on the Eastern Front during the Second World War.

Design Risk

The Concept of Design Risk

Design risk results from an imbalance between a strategy’s ends and the ways chosen to accomplish these. Because it contrasts strategic ends with the various methods designed to achieve them, this concept is termed ‘design risk’ Specifically, design risk focuses on whether the operational planner’s design will permit strategic success. The dangers that design risk poses to strategic success are clearly illustrated in the following historical examples which span more than two millennia and suggest the permanency of design risk in operational planning.

Donald Kagan, academic historian and author, describes Athens’ strategy for the Second Peloponnesian War as defensive in nature but characterised by a series of nuisance raids against Sparta that implied rather than actually projected Athenian naval power:

... the Athenians were to reject battle on land, abandon their fields and homes in the country to Spartan devastation and retreat behind their walls. Meanwhile, their navy would launch a series of commando raids on the coast of the Peloponnesus. This strategy would continue until the frustrated enemy agreed to make peace.10

This strategy, however, contained substantial design risk. For Athens ultimately to prevail, it needed to defeat Sparta on land. But Athens shrank from the cost of such a strategy, its planners unwilling to select the way necessary to achieve its strategic ends against a determined enemy. While Athens chose a way that emphasised the defensive, the nature of its enemy ‘made the Athenian way of warfare inadequate, and Pericles’ strategy was a form of wishful thinking that failed’.11

A more recent example of design risk occurred with US military operations in Indochina. Retired Colonel Harry Summers, author and military strategist, argues that there was a mismatch between the ends and ways of the US involvement in Vietnam. Put simply, the way selected by US strategists was inconsistent with their ends. Summers contends that this mismatch resulted in the selection of a way that was deeply flawed:

But instead of orienting on North Vietnam—the source of the war—we turned our attention to the symptoms—the guerilla war in the south. Our new ‘strategy’ of counterinsurgency blinded us to the fact that guerilla war was tactical and not strategic. It was a kind of economy of force operation on the part of North Vietnam to buy time and to wear down superior US military forces.12

Measuring Design Risk

The operational planner becomes concerned with design risk at that stage in the concept development phase when possible courses of action are identified. At that point, any imbalance between ends and ways becomes highly relevant. By adopting an approach comparable to that used to assess aspirational risk, the planner can determine the amount of design risk present in a specific operation. There are two ways to reduce the gap between ends and ways that characterise design risk: either the ends are contracted or the ways are expanded. The factors associated with design risk address both possibilities. The end-related factors that affect aspirational risk also influence this aspect of design risk. Thus, design risk can be mitigated by scaling back ends, extending the time to achieve the desired ends, prioritising and phasing the ends, or delaying a subset of the ends.

The expansion of the ways or course of action represents the other dimension of design risk. For example, the course of action can be accelerated in time to reduce the need to sustain resources. Planners can also design courses of action that do not emphasise attrition for success or employ the multiple elements of national power. Courses of action that can be calibrated in implementation, are viewed as legitimate, or allow measurable progress towards completion represent other methods to expand the strategic ways. Similar to the assessment for aspirational risk, the aggregate factor score can be estimated across these factors and the magnitude of design risk can be evaluated. This assessment operationalises the concept of design risk and allows it to be explicitly incorporated into the planning process.

Mitigating Design Risk

Since design risk involves an imbalance between ends and ways, the mitigation of this risk requires a closer realignment of these two strategic elements. This can be accomplished by focusing on the ends, on the ways, or on some combination of both. A number of examples from recent history illustrate various techniques aimed at reducing design risk in operational planning that remain relevant to operational planners today. The US-manned lunar program, for instance, used periodic assessment of progress towards the desired goal as a method to mitigate design risk. Inviting the participation of representatives from other elements of national power mitigates design risk because of their potential to influence courses of action. The US involved allies and coalition members in its campaign in Afghanistan to enhance the perceived legitimacy of Operation ENDURING FREEDOM. Courses of action can also be expanded by a change in organisational structure—including command and control relationships—to permit implementation of the selected way. This can be as simple as the replacement of one commander by another or as complicated as the creation of new organisations such as the US NorthCom or the Department of Homeland Security. Design risk can also be mitigated by an expansion of the specific course of action or an intensification of its implementation. The US firebombing campaign against Japan in 1945 represents an intensification of a selected way and a mitigation of design risk associated with the planning for the defeat of Imperial Japan.

Menu Risk

Menu risk refers to an imbalance between the ways and means of strategy. This type of risk occurs when the operational planner chooses from the menu of ways a strategic entree that is too expensive. Menu risk reflects the mismatch between the requirements of a given way and the means available to execute it. French strategists faced significant menu risk in the years following the First World War when the French government sought to improve its security by developing a network of alliances and international agreements. France anticipated that this system of alliances would allow it to defeat any nation that attempted to disrupt the European status quo but, as Army historian Robert Doughty observes:

In the quest for a military strategy, the French had to balance the conflicting requirements of organizing and equipping military forces that could simultaneously protect their frontiers, provide assistance to their eastern friends, and defend their lines of communication in the Mediterranean. Unfortunately, France did not have sufficient military forces for all these requirements. In the final analysis, French grand strategy proved inadequate ...13

By the late 1920s a gap had opened between French security strategy and its military capabilities. French inter-war strategy involved commitments to allies that required a military force capable of ‘strategic maneuver and of offensive action against Germany.’14 By 1930 France had lost the ability to initiate offensive operations against Germany and French strategists faced significant challenges resulting from menu risk.

Identifying and Responding to Menu Risk

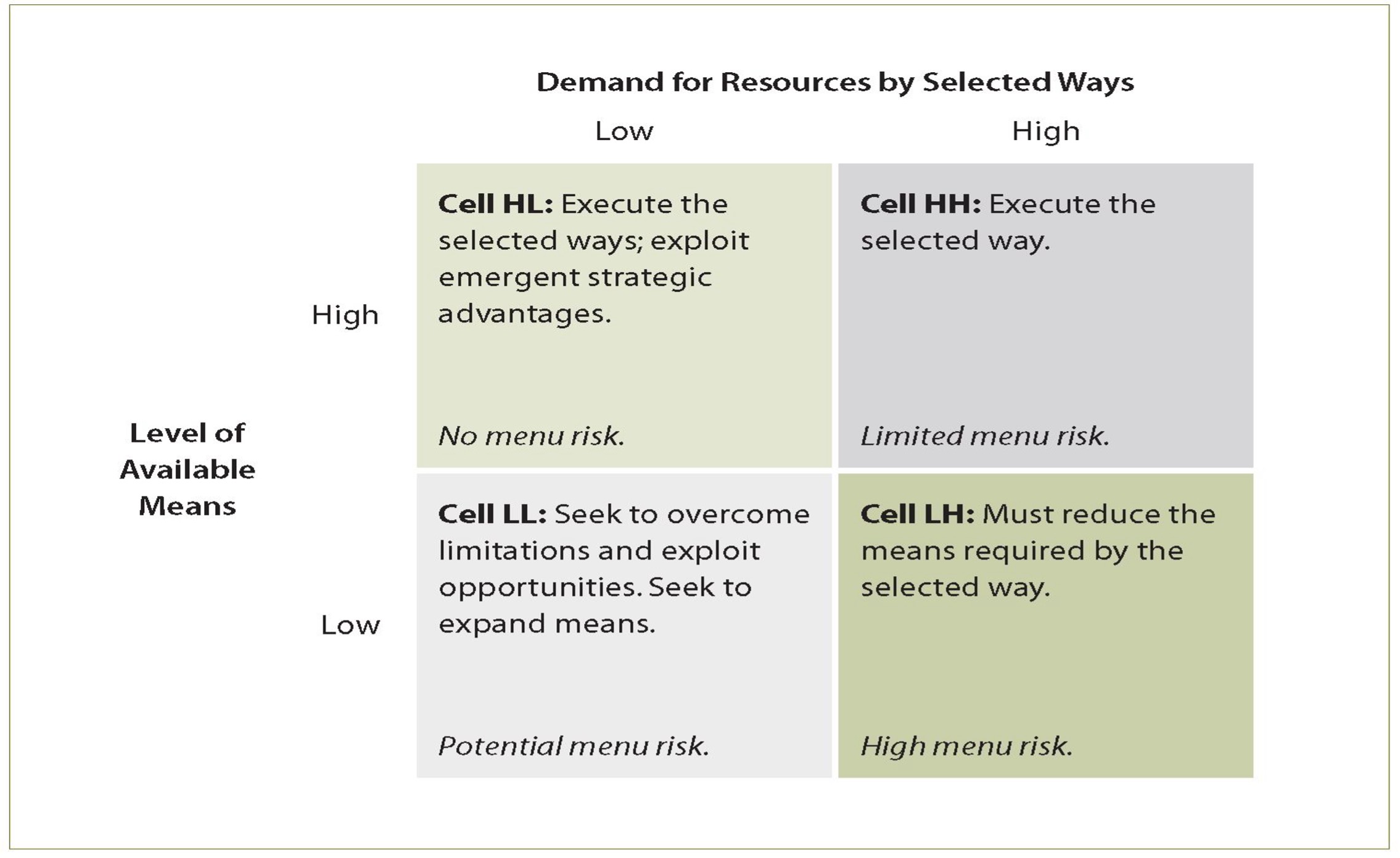

The threats-opportunities-weaknesses-strengths (TOWS) matrix of strategic analysis originally developed by business professor Heinz Weihrich can be modified to assist in the identification of menu risk and to suggest responses or techniques for its mitigation. In Figure 2, the available means are scaled on the vertical axis and range from low to high. A high level of means represents a strategic strength while low means are a weakness of the chosen strategy. The available means are then compared with the resource demands required by a given strategy. Strategies with a high demand for resources are more costly to execute and attract greater debate/ review because of their higher opportunity costs. Consequently, such choices are less attractive to planners and in this sense are ‘threatening’. Alternatively, strategies requiring a lower level of means generate less competition for resources, making their adoption and implementation easier. Consequently, they represent opportunities for the operational planner.

The cells in Figure 2 provide the operational planner with an indication of when menu risk might occur and options for response and mitigation. In cell HL (high means, low demand) the operational planner faces no menu risk. The means are abundant relative to the resources demanded by the selected way. Such a relationship suggests that the combatant commander should implement the selected way while exploiting any new opportunities that might emerge.

Likewise, in cell HH (high means, high demand) the operational planner should execute the selected way while also recognising the potential for menu risk. Although the available means are high, the ways demand significant resources. This imbalance raises the possibility of menu risk in the future. Consistent with the relationship presented in cell HH, the attrition strategy of the Western Front during the First World War generated a menu risk in which the belligerents ‘could succeed only by wearing down enemy resources and willpower at a faster rate than their own’.15

The bottom two cells represent resource-limited environments. In cell LL (low means, low demand), the strategist should seek to overcome the constraints of limited means and attempt to exploit the advantages inherent in a low cost way. Menu risk is possible if the modest demands of the way ultimately exceed the means available. Military historian and analyst Michael Handel notes that Israel’s small population has forced that nation to depend heavily on reservists and thus ‘wars must end quickly and decisively to avoid or minimize the economic paralysis caused by total mobilization’.16 The limited size of the Israeli armed forces has resulted in the selection of ways that attempt to reduce a military conflict to the shortest possible duration and to employ ‘capital intensive warfare’ to reduce casualties.17

Figure 2. The threats and opportunities associated with menu risk.

In cell LH (low means, high demand) there is clear menu risk. The selected ways are resource intensive while the means available to the strategist are insufficient. To eliminate this risk, the operational planner must reduce the level of means required by the selected way. The German Ardennes offensive of December 1944 exemplifies menu risk in such an environment. The putative objective for this offensive was ‘to cripple the attack capabilities of the Allied armies and chew up their divisions east of the Meuse.’18 With an attrition-like objective in mind, the selected way—a ground offensive—is highly demanding of resources. Hugh Cole describes the German armies in the Ardennes in 1944 as ‘fighting a poor man’s battle’ suffering acute logistics shortages.19 Although the German forces initially overwhelmed the Allied defenders, they were unable to make up their losses. The limited means available to Germany to execute this way were quickly exhausted. Menu risk ultimately doomed the German offensive to collapse.

Measuring Menu Risk

In a similar process to that used to assess aspirational and design risk, the operational planner must evaluate menu risk when formulating courses of action during the concept development phase. A number of factors can be identified that allow the planner to evaluate the resources and the ways available to support a course of action. These factors allow the planner to assess likely menu risk.

The planner will first need to assess those factors that affect available resources. As discussed earlier, the means will be affected by the ability of the planner to borrow or reallocate from other programs or receive resources from allies. The availability of host nation or in-theatre resources will also affect the means.

The value of a selected way will be governed by a variety of factors. For instance, the ability of a way to substitute technology for personnel or the possibility of calibrated implementation affect the risk associated with a specific course of action. The inherent risk in a chosen way is also influenced by its ability to be asymmetric in nature or accelerated in time or across space. The aggregate factor score obtained from the planner’s assessment of these factors can be qualitatively evaluated and will allow the planner to determine the extent to which menu risk is present in a specific course of action.

The various risk factors discussed above also imply a set of mitigation measures that can reduce the level of design risk present in any given plan. In this sense, the inventory of risk factors can be used to transition a plan across the threats and opportunities matrix presented in Figure 2. For instance, obtaining host nation support or reallocating resources from other programs can increase the level of means available for a plan’s execution and migrate it from cell LH (high menu risk) to cell HH (limited menu risk).

Conclusion

Lykke’s concept of strategic risk is underdeveloped and is of little practical use to staff planners or others involved in the design of theatre-level security strategies. This article attempts to operationalise Lykke’s concept by developing three new concepts of risk that are inherent in his model. These new risk concepts can be separately identified, measured, and ultimately mitigated by staff planners. The use of historical examples to develop and illustrate the concepts of aspirational, design and menu risk allows theatre-level planners to better understand the risks associated with a specific security strategy. This discussion moves beyond the creation of these new risk concepts by providing a useful set of analytical tools for the planner to determine the extent to which these risks are present and how they might be mitigated in the development of courses of action. Through a careful process of measurement of each of these risks, the planner can better identify which risk mitigation methodology is most appropriate. Such an approach to planning will increase the likelihood of choosing a course of action that will contribute to strategic equilibrium and the achievement of policy objectives.

Endnotes

1 Peter Drucker, The Essential Drucker: The Best of Sixty Years of Peter Drucker’s Essential Writings on Management, Collins Business, New York, 2008.

2 Peter L Bernstein, Against the Gods: the Remarkable Story of Risk, John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1996, p. 1.

3 Arthur F Lykke, ‘Towards an Understanding of Military Strategy’ in Military Strategy: Theory and Application, US Army War College, Carlisle Barracks, 1989, p. 6.

4 There are several assumptions that underlie equation 1’s deconstruction of strategic risk. The first is that strategic risk is additive. This follows from Lykke’s model in which strategy is defined as the sum of the ends, ways and means. The second assumption is that there are no interactive effects. To the extent that there is a significant covariance between the risks, equation 1 is not fully specified. Such interactive effects, however, are likely to be secondary to the primary effects attributable to aspirational, design and menu risks. Third, the model assumes that the risks are equally weighted. Again, this follows from Lykke’s original specification in which ends, ways and means are of equal importance in the formulation of strategy. Consequently, it is further assumed that the theatre planner weights each risk proportionately which, in this case, implies equally. Finally, the mathematical operators of absolute value are meant to indicate the assumption of symmetry in the effect of any imbalance. For instance, aspirational risk might exist because either the ends are in excess of the available means or the means are in excess of the strategy’s stated ends. This model recognises the possibility of an imbalance in either direction, but does not differentiate in its description of the magnitude of their contribution to the total risk of the strategy.

5 Paul Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers, Random House, New York, 1987, p. xvi.

Jeffrey W Taliaferro, Balancing Risks: Great Power Intervention in the Periphery, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 2004, p. 94.

7 Ibid., p. 95.

8 Andre Beaufre, An Introduction to Strategy, Praeger, New York, 1965, pp. 26-29.

9 Adam B Siegel, ‘Mission Creep or Mission Misunderstood?’, Joint Force Quarterly, Issue 25, Summer 2000, p. 113. Siegel contends that, in fact, mission creep represents a continuum of mission changes. It ranges from task accretion, which represents the accumulation of added tasks necessary to accomplish the original objectives, to mission shift, to mission transition when a mission undergoes an unclear or unstated shift of objectives, and finally to mission leap which is an explicit policy choice to change objectives and military tasks.

10 Donald Kagan, ‘Athenian Strategy in the Peloponnesian War’ in Williamson Murray, MacGregor Knox and Alvin Bernstein (eds), The Making of Modern Strategy, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1994, p. 33.

11 Ibid., p. 54.

12 Harry G Summers, On Strategy: A Critical Analysis of the Vietnam War, Presidio Press, Novato, 1982, p. 81.

13 Robert A Doughty, ‘The Illusion of Security: France, 1919-1940’ in Murray, Knox and Bernstein (eds), The Making of Modern Strategy, p. 466.

14 Ibid., p. 495.

15 Michael Howard, ‘British Grand Strategy in World War I’ in Paul Kennedy (ed), Grand Strategies in War and Peace, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1991, p. 37.

16 Michael Handel, ‘The Evolution of Israeli Strategy: The Psychology of Insecurity and the Quest for Absolute Security’ in Murray, Knox and Bernstein (eds), The Making of Modern Strategy, p. 545.

17 Ibid., p. 551.

18 Hugh M Cole, The Ardennes: Battle of the Bulge, Center for Military History, Fort Lesley McNair, 1964, p. 674.

19 Ibid., p. 663