Abstract

Any suggestion of the employment of Australian tanks in Afghanistan is frequently confronted with the sentiment that tanks are not applicable in the counterinsurgency environment. This sentiment, however, is historically inaccurate. The experiences of the Canadians and the Danes in their employment of tanks in Afghanistan highlight the impressive effectiveness of tanks in the combined arms environment in a counterinsurgency. Regardless, the topic is plagued by multiple fallacious theories. As a result, this article dispels many of these myths, and discusses the means by which the employment of tanks as part of the combined arms team will appropriately contribute to the protection of Australian soldiers and the achievement of success in Afghanistan.

As important as infantry are to ensuring the security of armoured forces, so too are tanks vital to the protection of our dismounted troops. We should never plunge our dismounted soldiers into confrontation with the enemy without first taking every precaution to ensure their protection.

- Major T Cadieu.1

Introduction

International consternation regarding the potential global security implications of insurgent and terrorist networks within Afghanistan has evoked a response which has included the actions of a wide range of coalition forces in Afghanistan. The aim is to deny a sanctuary to terrorists who threaten the stability of the global security environment and restore authority in an Afghanistan that does not harbour terrorism. Australian forces, deployed alongside many other nations, are involved in a complex counterinsurgency fight within Uruzgan province, employing a wide range of techniques and systems. Uruzgan is a physically tough, complex and demanding environment, complemented by an intricate and elusive system of societal networks.

This article will highlight the physical and human environment of current warfighting in Uruzgan, dispel many of the myths surrounding the contemporary employment of tanks, and espouse the employment of tanks as a part of the combined arms team to actively and appropriately contribute to the protection of Australian soldiers and the fighting effort.

Environment

Battlespace

Uruzgan is characterised by distinct geographical features, with bare mountain ranges separated by discrete valleys and belts of arable land concentrated along the banks of perennial water courses (ruds). The population is generally dispersed across rural areas, located in small and often remote pockets of land. The restrictive mountainous regions canalise traffic and limit movement between urban centres. The terrain around the rivers is much closer and the agriculture, especially grape trellises, hinders movement and provides extensive cover. Affecting all human activity and of significance to military operations are the weather effects, including a very hot and dry summer (35–50°C) and exceptionally cold winter with sub-zero temperatures and snow.

The population is tribal and centred around villages and tribes without strong loyalty to central and in many cases regional governments. These considerations combined with religious Pashtun culture significantly affect the human terrain.

Threat

A simplistic description of the threat environment is that it is an insurgency. This simple statement belies the complexity of Afghanistan’s social structures, the rise and fall of the Taliban, and the involvement of al-Qaeda and other terrorist organisations. In order to achieve its goal of returning to power, the Taliban, supported by other terrorist groups, must retain control of support bases and safe havens, and facilitate expansion of influence in rural populated areas. Attempts to undermine Coalition forces are executed through the extensive use of mines and improvised explosive devices (IEDs), the conduct of small arms attacks and ambushes, and where possible the application of indirect fire attacks. The tactics, techniques and procedures fostered by the threat are synonymous with the historical context of an insurgency, aimed at avoiding any type of decisive combat and thus effecting functional dislocation of conventional forces.

Counterinsurgency

In general terms, an insurgency is characterised by a specific group, or multiple groups, of guerrillas who use the complexity afforded by their integration into societal networks and the confusion created by blending into the civilian population to offset the advantages imposed by the destructive nature of conventional military technology. The environment in Afghanistan is no different. The concept of the insurgency is by no means new, and hard-earned lessons drawn from fighting a counterinsurgency (COIN) are drawn from campaigns including the UK in Malaysia, the US in Vietnam and Iraq, and the Russians in Chechnya and Afghanistan. Similarly, there is nothing new about societal networks and cultural influence having profound effects on COIN operations. While the conflict in Afghanistan is a different environment, important lessons can be appropriately drawn from the past.

The key to success in a COIN environment is the acquisition and maintenance of popular support,2 and therefore ultimately the undermining of the insurgent’s legitimacy. In military terms, the support of the population is seen as the ‘centre of gravity’ or the pivotal focus of the campaign. A deceptively complex task, success in this environment entails a robust information operations campaign, a means of rapid assimilation of a changing tactical environment, and a means of discriminatory targeting. A conventional military force is often strained in this environment as it is not trained or equipped to achieve much of the desired effect on the insurgent while at the same time avoiding collateral damage and, importantly, protecting the local population. The information operations campaign is a strategic level line of operations which is intrinsically linked to the tactical level of conflict; however, a discussion of this point is outside the scope of this article.

Rapid assimilation of a changing tactical environment can only be achieved through the situational awareness gained from an effective intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance network and rapid distribution of information to achieve the desired effects. Shortcomings in these areas will see a tactical team constantly reacting to insurgent successes, and therefore directing efforts to crisis management, rather than having an effect on the insurgent. The ability for forces to change tactics and techniques is also key to this type of campaign in that these changes force the insurgents to change their techniques, thereby potentially exposing their command and control networks, operational techniques and supply networks as they adjust.

The application of discriminating fires in the COIN environment is essential due to the insurgents’ propensity to operate in close proximity to civilians and civil infrastructure. The utility of a weapons system with the accuracy to destroy specific targets while leaving the target’s surroundings unblemished is vital (eg. application of fire into a specific room of a building without killing personnel in surrounding rooms or floors). Indirect fire systems are limited in these situations. Appropriate accuracy must be accompanied by a variety of ammunition types and weapon calibres in order not only to deliver precision in terms of accuracy, but importantly, to deliver the desired target effect. A fifty calibre machine gun, for example, will have a very limited effect on a thick mud-brick wall (such as an Afghan grape-drying hut3), but rounds that miss will penetrate countless walls, vehicles and people in the beaten zone, well beyond the target. Furthermore, it is likely in many circumstances that in order to achieve a high level of discrimination to protect civilians (the centre of gravity), Coalition forces will need to close with insurgent groups, and therefore become more exposed to a variety of weapons systems. As a result, intimate force protection for soldiers is vital.

Current Warfighting Context

Canadian forces are currently using tanks as a part of their combined arms teams in Afghanistan. An analysis of the Canadian lessons and operational reports has shown that they have been effective in this environment conducting a wide range of tasks. While some of the terrain differs from that in which Australian forces are operating, many of the lessons have direct applicability for Australian operations.

Australian forces currently deploy as combined arms teams. These will often consist of infantry, artillery Forward Observers and Joint Terminal Attack Controllers, and engineers mounted in Protected Mobility Vehicles (PMV) and ASLAVs. While ASLAVs achieve excellence in cavalry, reconnaissance and surveillance tasks, they have significantly less protection, mobility and accuracy, compared to the current Australian tank: the M1A1 AIM SA. The ability for field commanders to select M1 Abrams to undertake a range of tasks as a part of the combined arms team provides flexibility and the opportunity to more effectively combat insurgents in the Afghan COIN environment.

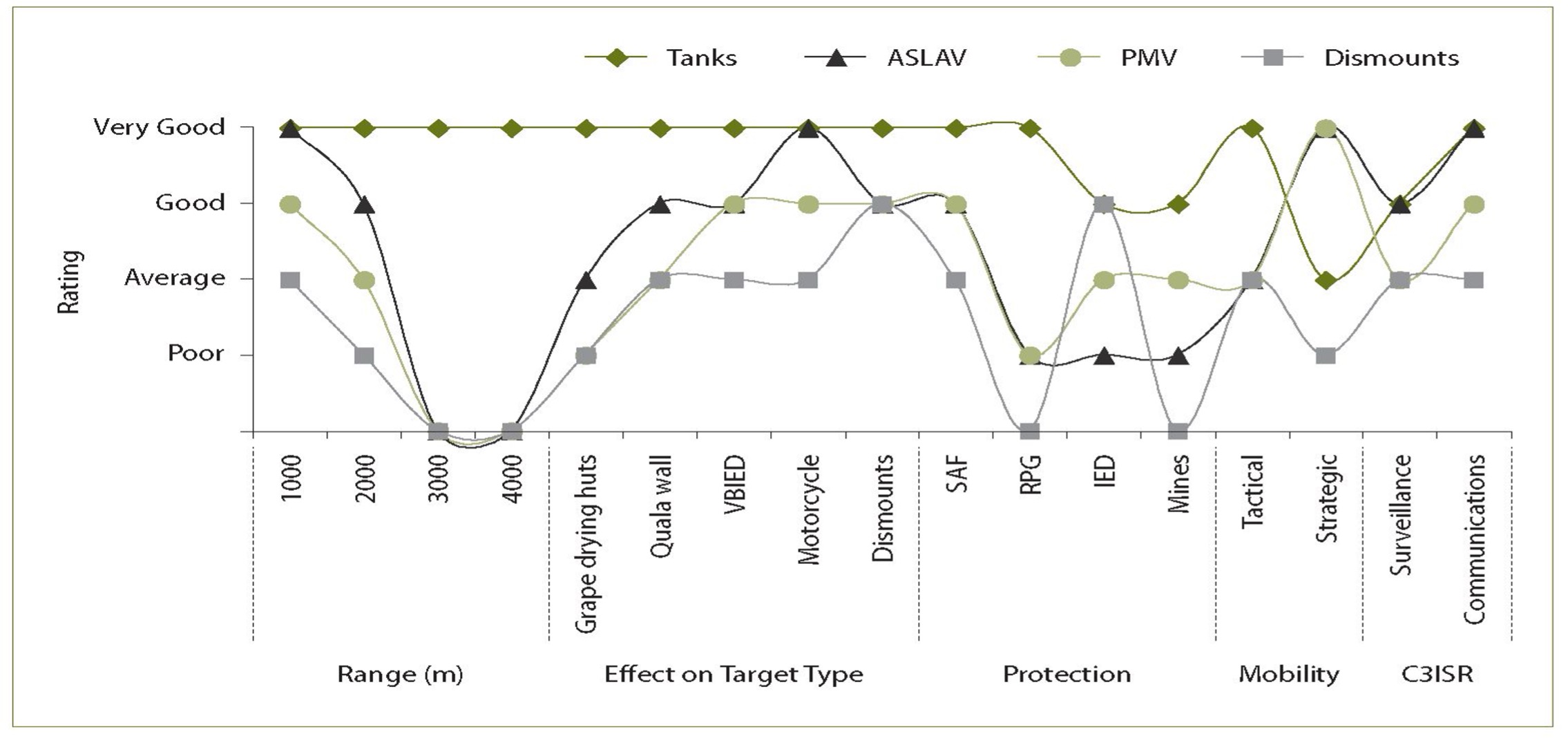

In order to analyse the conduct of operations in Afghanistan, some of the key considerations include weapons ranges, target effects, level of protection, mobility, ability to provide surveillance, and ability to enhance situational awareness and communications. Regarding these considerations, Figure 1 is a comparative analysis of dismounts, PMVs, ASLAVs and tanks.

Figure 1. Force Element Comparison4

Myths Surrounding Tank Employment

There are many perceptions regarding the roles applicable to the employment of tanks, and to the capabilities provided. These perceptions are often flawed in that their origins are generally contrary to factual evidence and irrefutable lessons learned from historical tank employment. Several common myths will be dispelled with the intent of aligning the highlighted misconceptions with logical deductions.

Terrain. One of the most common allegations made with regards to the employment of tanks in Afghanistan is that the terrain is unsuitable for tank operations. To the contrary, tanks represent the pinnacle of land mechanised or mounted mobility. Australia has already deployed a variety of A and B vehicles in various roles in Afghanistan. The M1 Abrams has superior tactical mobility to any of the currently deployed systems and although terrain is certainly a limiting factor for ground operations, its effects are less pronounced for tanks than other vehicles. Mission profiles for maximum benefit of this mobility will be discussed later.

Infrastructure. Many comments, particularly from personnel unfamiliar with tanks, suggest that the operation of tanks on anything other than hard packed earth is unworkable. Simple physics, however, dictates that because of the large surface area encompassed by the track of the tank, ground pressure, as highlighted in Table 1, is remarkably low. Obviously the pressure distribution changes when negotiating an obstacle and the application of hard turns on a soft surface will clearly cause disfigurement to the surface; however, the mass of the M1A1 AIM SA (61.3 T) does not automatically result in the destruction of roads. Conversely, the low ground pressure reinforces the enhanced mobility attributed to the operation of tanks which can assist in avoiding IEDs.

Table 1. Ground pressure comparison.

|

Object |

Mass (kg) |

Ground Pressure (PSI) |

|

Man5 |

80 |

8 |

|

Mountain Bike5 (with rider) |

95 |

40 |

|

Passenger Car6 |

1300 |

30 |

|

Tank6 |

61300 |

13.8 |

Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs). Like the current operations with ASLAVs, tanks require protection from IEDs in targetable locations which cannot be avoided. The Canadian experience in Afghanistan and the US experience in Iraq highlight the potential disruption caused by IEDs that are well sited and voluminous in composition. Australia’s experience with PMVs has also shown that predictable locations such as one of very few creek crossings available to a PMV are a lucrative target for IED emplacers. The ability to identify the likely channelling effect of a such a crossing, and therefore assess its vulnerability to IEDs, highlights the advantages gained by the possession of a level of mobility that enables far greater options in the selection of sites for crossing obstacles. Acknowledging that not all IED sites are predictable, the enhancement in crew survivability against IEDs provided by underbelly armour and slung seating (both part of the Tank Urban Survival Kit program7) promote confidence that in the contingency that a tank cannot avoid an IED strike, the crew has a superior expectation of survival. Finally, it should be noted that repair of a separated track in the field is a crew task, and far more achievable than replacement of a wheel station on a four or eight wheeled vehicle.

Combat Service Support. The fact that the tank is a heavy Combat Service Support user is by no means a new concept, and should not be disregarded in considering the employment of the tank. Much like many tools of modern warfare including attack helicopters and fighter aircraft providing close air support, logistic bills are an integral part of operations, and not necessarily a limiting factor. It should be noted, however, that many allegations surrounding fuel usage rates are largely inaccurate. The operational tempo and indicative tasks identified in Table 2 are a realistic estimate of tank troop operations in Afghanistan. To extrapolate, a tank will therefore use an average of approximately 500L diesel per day (150L per hour of operation8) which, in comparison to a CH-47D using 1350L per hour of operation,9 is not extravagant. This usage rate is certainly achievable in terms of resupply from a forward operating base (FOB) given a robust resupply system. The fuel usage rate for the M1 in comparison to other fuel users (particularly aviation) is of such relative insignificance to both US Army and USMC that, although the M1 is more efficient using diesel, they run their tanks on JP5 or JP8 (av-gas), as the tank is the minor fuel user. Finally, of relevance is the fact that while conducting static tasks, the vehicle can maintain charge to its system using its External Auxiliary Power Unit (comparable fuel usage to running a small generator). As a result, fuel usage while on standby for quick reaction force (QRF) tasks in overwatch and in static security positions is minimal, while the tank continues to provide enhanced security and response.

Recovery/Repair. Contrary to common perception, repair and recovery during tank troop operations are well practised and efficient drills, and an integral part of planning for every mission. To facilitate efficient repair and recovery, the requirements for a troop and a squadron are equal, and a squadron A1 echelon is essential. Basing the echelon in the FOB, forward repair and recovery can be effected through organic assets, while base repair and routine maintenance should be a function of routine operations at the FOB. To expand, the security issues associated with forward recovery can be somewhat mitigated by the troop’s capability for self recovery to either a pre-designated equipment collection point or a FOB. Tank troops are well versed in self recovery and each vehicle has four mounting bollards and carries two tow cables to facilitate recovery if required. The procedure is as simple as any vehicle in the troop connecting the tow cables and dragging the damaged vehicle to a suitable location for recovery by the A1 echelon.

Table 2. Estimated monthly fuel usage per tank10

|

Mission Type |

Indicative Frequency of Mission per Month |

Monthly Fuel Usage Per Tank (Estimated) |

|

FOB security including routine maintenance at FOB |

9 days |

450 L |

|

Overwatch from SBF location (approx 30 km from FOB) |

12 full day missions |

8400 L |

|

QRF reaction task (approx 30 km from FOB). Includes break in, secure mission and extraction) Approx duration 6 hours. |

5 |

4500 L |

|

Urban clearance patrol including assault and exploitation on an objective. Approx duration 6 hours. |

5 |

4500 L |

|

Total usage: |

|

17850 L |

Accuracy. The concept that the tank is indiscriminate and will undoubtedly cause greater collateral damage than other forms of offensive action is false. Operations in Iraq and Afghanistan have shown that appropriate application of tanks in operations have reduced collateral damage. This is reinforced by the experience of the Canadian tank squadron deployed to Kandahar, where the commander highlighted:

...suggestions that the use of tanks has alienated the local populace more than other weapon systems have proven completely unfounded. Since commencing combat operations...tanks have killed dozens of insurgents in battles throughout Kandahar, yet there has been no suggestion of civilian deaths attributed to tank fire during the entire period. Equipped with a fire control system that allows our soldiers to acquire and engage targets with precision and discrimination, by day and by night, the tank has in many instances reduced the requirement for aerial bombardment and indirect fire, which have proven to be blunt instruments...a strong case can be made that tanks have actually reduced collateral damage in the AO.11

The Commander of the International Security Assistance Force (COM ISAF) released a tactical directive in July 2009 which specifically directed the cessation of air-to-ground kinetic activity where certainty of the absence of civilians could not be ascertained and where a battle damage assessment was unable to be performed.12 It follows logically that the combined arms assault, using tanks for their mobile precision, is an exceptional means of safely and effectively achieving the mission while fulfilling COM ISAF’s intent.

Employment of the Tank in Support of Australian Operations

A popular interpretation of the relevant employment of the tank is summed up as ‘There are no enemy tanks in Afghanistan to destroy, so why would we need a tank?’ The making of such a statement, other than to get a rise from Armoured Corps officers, illuminates a limited understanding of military history and combined arms operations at the tactical level.

Having considered the current warfighting context in Uruzgan, there are several roles of key significance by which employment of the tank is assessed as having impressive potential to improve Australian operations and protect both Australian and Afghan National Army soldiers. These mission profiles include employment as part of an armoured QRF, as part of the exploitation of objectives using the combined arms assault, overwatch of dismounted operations in a support by fire (SBF) position, kinetic targeting in support of dismounted operations, and the application of the demonstration.

The Armoured Quick Reaction Force

The first and perhaps most obvious utility for the tank in Afghanistan is as part of an armoured QRF in support of offensive, defensive or security operations. The structure of the QRF is open to a variety of configurations, dependent on the task and threat environment; however, the following structure can be used across a variety of operations:

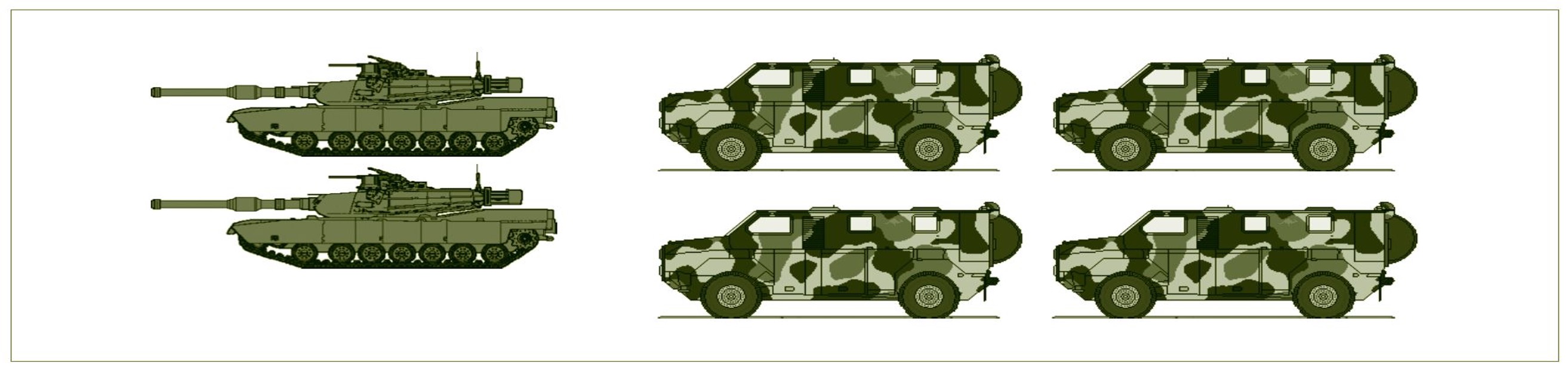

a. two tanks with four armoured personnel carriers (APC) or PMVs (Figure 2) for security operations and low level operations; and

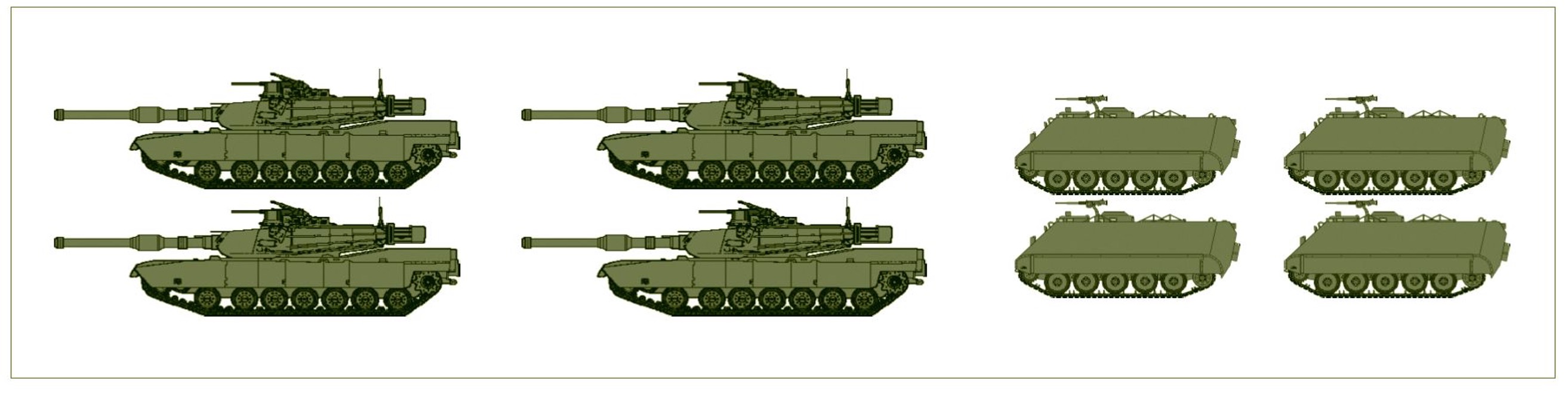

b. four tanks and four APCs or PMVs (Figure 3) for a higher anticipated threat.

The rationale behind the employment of the armoured QRF, as a combined arms grouping in support of an array of operations is associated with the inherent mobility, protection and firepower attributed to the tank, coupled with the ability to achieve dismounted tasks where required.

Figure 2. Armoured QRF Light.13

Figure 3. Armoured QRF Heavy.

Enhanced mobility for the QRF is paramount for several reasons, including being able to avoid likely insurgent target areas of interest (e.g. channelling points may well be targeted using mines/IEDs and small arms ambushes). Furthermore, enhanced mobility enables breaching of hastily established blocking points, which, in turn reduces these obstacles for any less mobile following vehicles. The infamous Blackhawk Down 14 saga is a prime example of a situation where an armoured QRF would not have been blocked by the makeshift barricades that significantly hampered the progress of the wheeled QRF in Mogadishu. Finally, the ability to create alternate exfiltration routes reduces the likelihood for targeted exfiltration, and therefore the risk of exploitation through pursuit.

Maximum protection for the QRF is vital. It is highly advantageous to employ a level of protection which enables the QRF to close with a potentially lethal threat and achieve the required level of disruption to secure an incident site, thus setting the conditions for success in exploitation of the incident site. The tanks leading the QRF can call dismounts forward to clear vulnerable choke points as required, while the tanks will bear the brunt of small arms fire ambushes and can provide support for the troops clearing the ground.

The distribution of the required level of firepower to neutralise a given threat necessitates the employment of weapons systems with a broad spectrum of effects and utilities to be effective. The Australian tank (M1A1 AIM SA) employs a diverse range of weapons systems, including two 7.62mm machine guns, a fifty calibre commander’s weapon station, twelve 66mm grenade launchers, and the 120mm cannon as its main armament. The system also offers a range of munitions which enable the crew commander to assess the required effect on the ground in a given situation and apply an effective and appropriate response. A relevant consideration here is that a single 120mm high explosive round will cause less collateral damage in an urban environment than numerous rounds from a fifty calibre machine gun to achieve the same effect.15 In addition to the advantages of employing varying levels of firepower, the application of such firepower from the tank specifically facilitates success in target discrimination, ensuring the minimisation of collateral damage from the unnecessary employment of air support or indirect fire.

The Combined Arms Assault

Another effective means of employment of the tank in Afghanistan is either in the deliberate or hasty combined arms assault on complex or hardened objectives. The effectiveness of this technique has been reinforced on multiple occasions by Canadian combined arms teams in Afghanistan, specifically comprised of heavy armour (tanks) with armoured engineers16 in order to achieve the combined breaching and shock action necessitated by the situation.

One of the common frustrations experienced by Australian troops in Afghanistan is a lack of manoeuvrability while in contact. It is a common occurrence that when in contact, Australian troops are limited in exploiting insurgent positions because of suppression by small arms fire. In addition, if the level of small arms fire renders friendly positions untenable, the clean break becomes problematic, as dismounted elements lack the firepower to achieve the shock action required for an effective clean break. A synchronised, concentrated weight of fire on an objective achieves the necessary temporary neutralisation of the insurgent objective for unhindered friendly manoeuvre.

The employment of the tank/infantry combined arms team in reaction to engagement by small arms fire and rocket propelled grenades applies the most tangible of the tenets of manoeuvre warfare—shock action—to maximum advantage. Having applied the firepower and protection provided by the tanks to rapidly close with the insurgents, infantry are then able to clear the insurgent position or complex with minimal risk. Not only does this approach enable the exploitation of insurgent complexes and strongholds, the structure employed provides the flexibility to react to a changing tactical environment with speed and efficiency. The importance of maintenance of manoeuvrability in contact is paramount.

Support by Fire

Current operations in Afghanistan have seen ASLAVs employed in a support by fire (SBF) role for overwatch tasks in support of dismounted operations. Although this has generally been an effective means of overwatch, mobility and firepower can be enhanced, and therefore reduce the risk of disruption, by using a tank troop in SBF.

The enhanced mobility achieved by the tank allows flexibility in choosing SBF locations. In addition to this advantage, targeting by IEDs can be significantly reduced by the selection of unpredictable routes with alternate withdrawal routes, achievable given the enhanced mobility of tanks.

SBF positions, particularly within and firing across the Baluchi Valley, have at times lacked effectiveness due to the vast ranges of targets compared with the effective range of weapons used. Noting that the accuracy of 25mm rounds in excess of 2000m suffers exponential decay, the comparative 4000m range afforded by the M1A1 AIM SA by day or night, static or moving, combined with its remarkable accuracy, presents a significant advantage in reducing collateral damage. Furthermore, the exposed forward slope firing positions often adopted by ASLAVs in this role can be avoided considering the extended range of the tank. The benefits of this would become irrevocably evident if insurgents were to adopt and employ any capable anti-armour weapon.

Kinetic Targeting

Tanks will likely not augment dismounted patrols by moving with the patrol. Regardless, there is significant wisdom in the utility of the tank as part of the mission profile for kinetic targeting. Historically, kinetic targeting has been affected by attack helicopter and close air support, which, while generally effective, are limited by weather effects, their ability to deliver sustained direct fire and conduct target exploitation. The proposed means of affecting this level of targeting includes moves by a tank pair or troop to designated hides, from which a number of ‘be prepared to’ tasks are allocated. From these hides, vehicles can react to designated objectives or to unexpected situations as required. The resultant effect on the insurgent includes both heavy sustained direct fire in all weather conditions and the option to achieve exploitation on necessary objectives.

Demonstration

The psychological effects of a planned and targeted show of force include two key issues: insurgent shaping and population reassurance. The insurgent is shaped in his planning and conduct of operations, and the local population is reassured that its security and welfare are of such importance to coalition forces that they are willing to employ such visibly formidable means to oppose the insurgency. Anecdotal evidence of these effects is apparent from operations in Mogadishu, whereby US forces employed tanks as their QRF. The deployment of tanks caused immediate dispersal of Somalian crowds.17

The application of a show of force must be an unpredictable and uncommon mission. Frequent application of such missions will dilute the psychological effect through familiarity. This, too, was realised by the same US force in Somalia under a different Brigade Commander in its excessive application of demonstrations, whereby the psychological effects of demonstrations became obsolete.18

Conclusion

Counterinsurgency operations have been historically complex, compounded by the fact that many conventional force packages are generally ill-equipped to meet the broad range of tasks and requirements of COIN operations. Tanks offer exceptional utility in support to Australian forces deployed to Afghanistan by providing the field commander with improved options in the prosecution of his mission and in reducing the options available to the insurgent commander. The applicability and capability of tanks to assist in jungles and urban terrain have often been initially misjudged by military commanders throughout history. History has shown, however, that the tank’s presence, extreme accuracy and long-range weapons systems, protected cross-country mobility, enhanced surveillance systems and solid communications enable success in a wide range of mission types. Tanks require combined arms integration and intimate protection to perform tasks in this environment, and when employed in such a manner can have impressive results. Although not suitable for every mission, every time, tanks assist in avoiding predictability, enable discrimination in the application of force, and increase the options available to the tactical commander. Australia has the means and the ability to deploy this capability to support Australians on operations in Afghanistan. Doing so will ultimately assist in saving lives and achieving mission success.

Endnotes

1 T Cadieu, ‘Canadian Armor in Afghanistan’, Canadian Army Journal, Vol. 10.4, Winter 2008.

2 L Thompson, The Counter Insurgency Manual, Lionel Leventhal Ltd, London, 2002.

3 Cadieu, ‘Canadian Armor in Afghanistan’, p. 20.

4 Table is based on a qualitative analysis of the performance of different systems against selected criteria. Note that predicted IED protection is higher for tank than PMV as the analysis of tank includes underbelly armour as per the Tank Urban Survival Kit (TUSK) upgrade program.

5 S Brown, ‘Bicycle Tyres and Tubes’, <http://sheldonbrown.com/tires#pressure>

6 J Allen, Jeep 4x4 Performance Handbook, Motorbooks, MBI Publishing Company, p. 16.

7 TUSK is a progressive US project comprising a large quantity of enhancements. While Australian tanks have not and will not adopt all enhancements, the slung seating and underbelly armour are assessed as highly advantageous for the warfighting context of Afghanistan.

8 The figure of 150L per hour is derived from the author’s experience in the field as the Tank Officer Instructor at the School of Armour. Fuel usage rates are not constant and cannot be accurately deduced for hourly usage, or per kilometre. This is due to different consumption rates dependent on ground surface, ground moisture content, weather, type of mission and aggression in movement. It should be noted that, contrary to common belief, the tank does not use the same quantity of fuel at idle as it does at higher revolutions.

9 ‘US Military Aircraft’, <http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/systems/aircraft>

10 This table is not sourced from standing force element work ratios. It is the result of an analysis of assessed reasonable ratios.

11 Cadieu, ‘Canadian Armor in Afghanistan’, p. 10.

12 Unclassified information released from COMISAF Tactical Directive – July 2009.

13 This is a suggested format. Doctrinal employment is not prescriptive, as different tactical situations will dictate the requirement for different QRF construction. Note that M113 can be used in conjunction with PMV if required (eg. organic squadron medical M113 and fitter’s track may be used in conjunction with attached PMV containing dismounts).

14 M Bowden, Blackhawk Down, Atlantic Monthly Press, Berkeley, California, 1999.

15 The rationale here is that the local effects of the 120mm round are devastating but, unlike a less accurate system such as the 12.7mm machine gun or the 25mm cannon, the surrounding infrastructure remains unaffected.

16 Cadieu, ‘Canadian Armor in Afghanistan’, p. 12.

17 Personal conversation between Colonel Mick Reilly and US Tank Company Commander, 1993.

18 Ibid.

19 The assistance of Colonel Mick Reilly is acknowledged in the writing of this article.