[Editorial note: This speech has been edited for clarity.]

[ZACH LAMBERT]: My name is Major Zach Lambert. I am here today to talk on mobilisation. I’ve done a fair amount of academic studies on this topic, most recently a Fulbright Fellowship in the United States where I looked into mobilisation in detail. I have a fairly significant operational background and previously I was in the divisional staff as a joint logistics planner. With me today, I have Major David Caligari.

[DAVID CALIGARI]: Good afternoon. I’m currently the operations officer of the 3rd Battalion of The Royal Australian Regiment and I’ve been in the Ready Battle Group for the last two years, and also as a junior officer. I’ve also served within the Australian Amphibious Force headquarters and mobilised and deployed at short notice to a regional contingency operation in Vanuatu. We are here today to discuss mobilisation. This is an important topic, which has been in the news a bit lately.

Mobilisation is the process of readying military capabilities and marshalling national resources for military operations to defend the nation and its interests. More particularly, mobilisation is the preparation of forces following specific government direction for operations, activities, and actions (now called investments). Mobilisation occurs across four phases. The first is preparation, the second is mobilisation activities, the third is the conduct of operations, and the fourth is demobilisation.

Australia is not new to this game. We have been mobilising since 1885, when Australia deployed 750 soldiers and 200 horses from the port of Sydney to the port of Sudan to participate with the British in the Mahdist War. If we move forward in history, we can see instances of mobilisation in our near region, specifically within the histories of those ADF members still serving. You can see mobilisation occurring across Operation Morris Dance, in East Timor under Operation Spitfire and in Operations Bel Isi and Lagoon, which are both deployments to Bougainville. Further, mobilisation occurred domestically in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Further, in the last 18 months, the 1st Battalion mobilised and deployed soldiers at short notice to Afghanistan for a non-combatant evacuation operation. Separately, my own 3rd Battalion contributed soldiers at the request of the Government of the Solomon Islands to support security there in December last year (2021).

So why are we discussing mobilisation if Australia has been doing it for a while? Mobilisation has become important, and it is all about crisis warning time. The Defence White Paper in 2016 stated that we would have 10 years notice to mobilise to the highest degree to respond to crisis—which is a lot of time to prepare. However, our geostrategic context has changed, the world is less certain than it was back in 2016, and we no longer have the 10 years of notice. This shift in strategic circumstance is what the 2020 Defence Strategic Update told us. Consequently, mobilisation has become even more relevant today than it has been in the past. So what are we going to cover?

[ZACH LAMBERT]: Today we are looking to cover four main topics. The first is to provide an overview of what the stages of mobilisation look like at the strategic level. Following that, we are going to look at some of the tactical components of how we might execute those stages of mobilisation. The second point is to look at the strategic model across all four stages and how it might be applied. Thirdly, we will move into the specific tactical details of how mobilisation affects you within the unit and what you might expect to see at the lowest level. In our fourth and final point, we will discuss some of the challenges that these mobilisation activities pose to all of us.

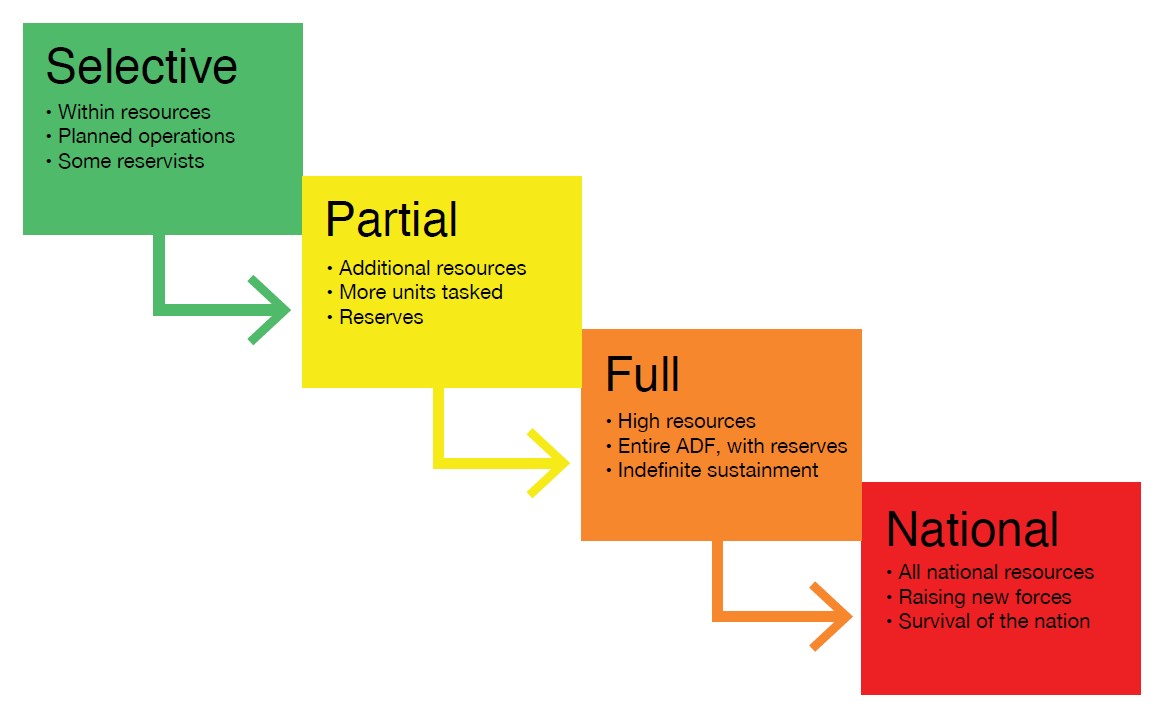

First of all, I’d like to bring your attention to your screen. As Figure 1 shows, there are four stages of mobilisation—running from selective through to partial, then to full and then finally national mobilisation. At the selective level, you can take these actions to mean scheduled and planned operations or activities that we know are coming and that we have specific units allocated to and prepared for. This might include some reservists, but broadly it will mainly operate with the forces that we have at our disposal on short notice. When we move on to partial mobilisation things get a little bit more serious and this might include the activation of the Reserves to a certain degree—such as what occurred during the Operation Bushfire Assist activities in 2019–2020. When we move further on into the full mobilisation stage, this looks a lot like utilising the entire ADF as well as all of the Reserves, and this is not something that can be done within current Defence resources. This level of mobilisation will require significant support from around the country. Finally, we move into the national level of mobilisation, or the national stage. These activities would look similar to what you would have expected during the First World War or the Second World War, where the entire country is focused and retooled specifically to support military activity, primarily because this stage tends to require a threat to the nation and a situation where the survival of the nation is in question.

Figure 1: Four stages of mobilisation

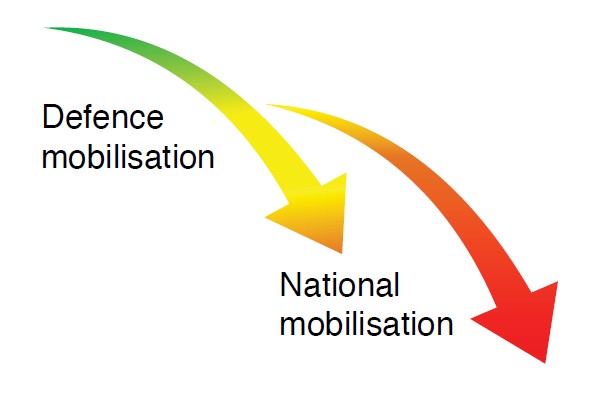

Now this is one way to look at this system. However, it is not the only way to conceptualise the process of mobilisation. In another example [as at Figure 2], you might break it down into two separate tranches, one containing the selective and partial stages, and one containing full and national stages. Instead of the four phases outlined in Figure 1, this might look like an area of defence mobilisation within defence resources, and another area of national mobilisation.

Figure 2: Two tranches of mobilisation

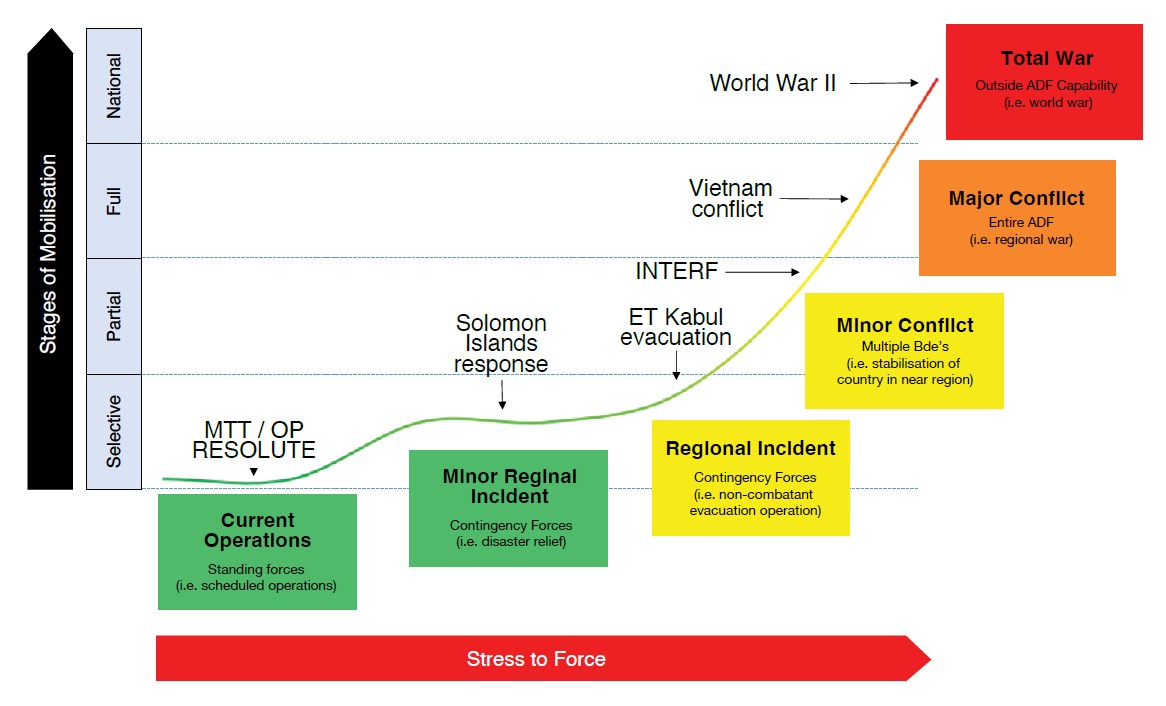

It is important to note as well that none of these activities can occur without clear direction from the government, and authority to conduct national level activities doesn’t derive solely from the Department of Defence. Almost all other government departments are also involved. With this in mind, we want to break the concept in Figure 2 down into more detail. How exactly does it work? If you have a look at Figure 3, you will see the stages of mobilisation increasing up from selective to full. On the bottom of the diagram, you will see the stress—being the number and complexity of tasks and the amount of resources to be incorporated into the plan—that is generated on the force. The line between those axes looks at the increasing level of stress to the force applied from left to right as you move up through those mobilisation stages, which could go from current operations that are planned and scheduled all the way up to a major conflict that involves the entire ADF. These activities have occurred before, and so to get a real understanding of this, let us look at some examples.

[DAVID CALIGARI]: I mentioned that the 3rd Battalion is currently the Ready Battle Group, but the reality is that you do not need to be in a ‘prepared contingency’ force element (like the Ready Battle Group) to be part of, or involved in, mobilisation activities. Right now, large parts of the ADF are contributing through various missions to support security cooperation with regional partners or ongoing operations. An example would be the mentor training teams that are going to places like Papua New Guinea and the Philippines, as well as the ADF’s enduring contribution to Operation Resolute, which is the military contribution to whole-of-government efforts to protect Australia’s borders and offshore maritime interests. In these instances, forces elements are designed (including a number of personnel who come together for a specific mission), practised, and then deployed. This action is undertaken at the lowest level of selective mobilisation. The next step occurs when extra preparation for forces is needed. When we move to place more stress on the force, we see the benefit of contingency force operations. We will use the examples as shown at Figure 3 to make this process clearer.

Figure 3: Stages of mobilisation and associated stress on the force

First, let’s start with mobilising the Ready Battle Group to respond to a minor regional incident. The 3rd Battalion, in December 2021, sent a small team overseas at the request of the Government of the Solomon Islands to support them in dealing with a deteriorating security situation.

Next, you can move to a regional incident at the high end of selective mobilisation, and an example of that is the August 2021 non-combatant evacuation in Afghanistan. One of the key differences that made it a more significant event is the presence of the battalion headquarters, providing the basis for force expansion. Because of the size of the contribution, in this scenario there was a need to transition ownership of the high-readiness force element from the 1st Battalion to the 3rd Battalion after the operation had commenced. This transition was easily achieved within the level of readiness as the forces changed roles, as both battalions were practised in performing the role of Ready Battle Group.

We then move forward to a minor conflict, moving up into the second stage of partial mobilisation. Here we can look to the example of East Timor and the deployment of Operation INTERFET, which consumed the ready force elements and required a much larger contribution of forces to form a task force for operations. We then continue to move up through the stages, where we can see the Vietnam conflict as an example of full mobilisation. This mobilisation was notable, as a key element of this type of mobilisation is the requirement for national service. In this instance, it was essential that the ADF expanded its force to sustain operations, which required that extra degree of capability.

The final step would be something many of you would have guessed, a world war. As Zach mentioned, this requires the entirety of the country to be geared towards supporting the military and other instruments of government to achieve what is needed in conflict on behalf of our national interests. Having described the stages in theory, we are now going to look more specifically at how a system of national mobilisation would play out.

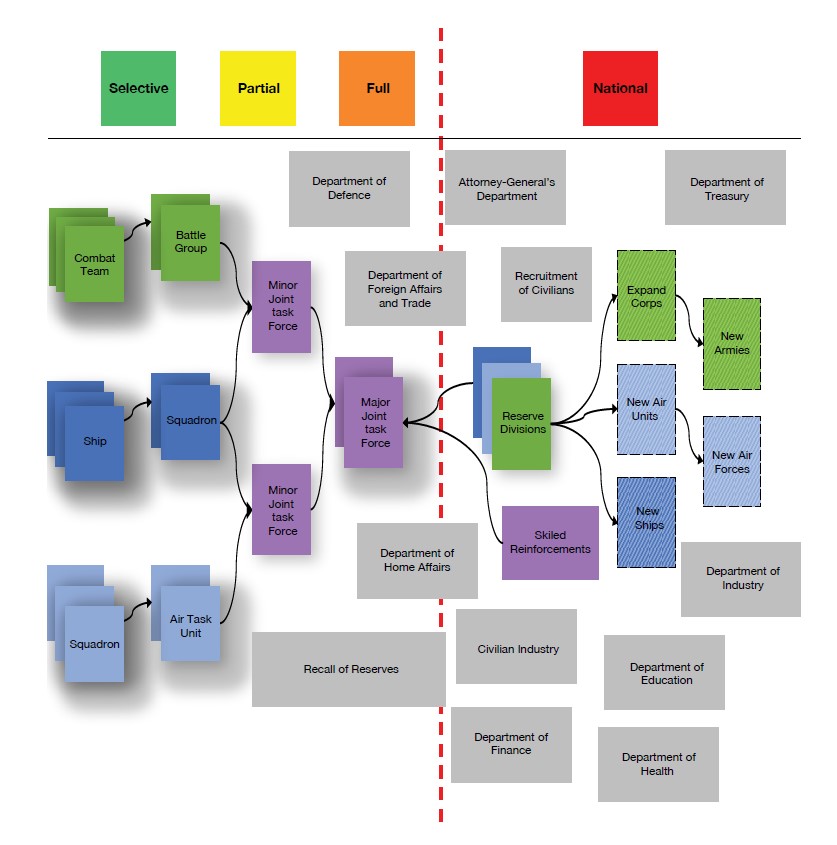

[ZACH LAMBERT]: In order for us to go further into this topic, we need to have an understanding of how national mobilisation affects what would occur. We have prepared a stylised and simplistic view of this mobilisation just to discuss what it might look like (see Figure 4). You can see we have the phases of mobilisation along the top of the screen. You will note that there is a big distinction [indicated by the red dotted line] between the full level of mobilisation and the national level, and there are many complex activities that occur at the national level. However, mobilisation starts at the lowest level, being the groups of teams that we create in each of the services. This might be as simple as a combat team. This might be as simple as an individual platoon for a specific task.

Figure 4: National mobilisation system

Yet whatever level of mobilisation occurs, it is done specifically to generate a particular outcome aligned with government requirements. As the mobilised elements build, we group them together into the next level up. In this case, we are using the example of battle groups, although it is certainly not the only formation that we could use to illustrate the process of moving from selective mobilisation into the start of partial mobilisation. The next level is our minor joint task forces. As we combine elements from across the services, we put them in a position where they might have to operate together, and the key thing here is the headquarters in charge of the task forces tend to be joint headquarters to generate the best effects. This amalgamation moves us more towards the partial level of mobilisation.

The next level occurs when we are approaching a full level of mobilisation. This step commences when we develop minor joint task forces into major joint task forces, and we start to include specific tasks and teams from other government departments. So, for example, when the entire Department of Defence becomes involved, we might get specific guidance from the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade if your operation is occurring overseas. Or we might get some input from the Department of Home Affairs if it happens to be in Australia. The combination of these factors makes it quite a complex and all-encompassing task, and at this stage you start to tap into what assets are in the national support base that you might need to support these activities. While we might have previously conducted the recall of some Reserve force elements, as this phase of mobilisation progresses we may at some need to start recalling the entirety of the Reserve, which is a significant activity. Those Reserves then plug into our major joint task forces, and either fill gaps or provide discrete capabilities and combat organisations that we specifically need to send overseas.

As we move on from there, we might look at the requirement to start moving skilled reinforcements into the forces that are on operations. That might look like, for example, additional doctors or armourers that we have pulled from their civilian jobs to come and provide support. It might also include the requirement to start recruiting civilians, particularly for those key specialist jobs. Until this point, there are concrete historical examples of every element of mobilisation we have discussed, but once we move past this stage, into national mobilisation, what might occur becomes highly theoretical. We may look to start involving other elements of Australian society that have important roles to play—for example, the involvement of civilian industry to start retooling to provide support to the force, or potentially the Department of Finance to prepare future funding.

National mobilisation is an exceptionally expensive and complex undertaking, particularly when we consider options to expand our forces. This may involve expanding our existing Army corps, or moving towards new air units and potentially new or replacement ships to expand the Navy. The final stage of what a national mobilisation might look like, again in a very simplistic fashion, would be full and total mobilisation across both the force and other elements of Australian society. This would involve, for example, the Department of Education and the department of health, which would provide new recruitment streams and capabilities that we need to reinforce long term over the course of years, rather than months. We also need to start looking at how this may affect the economy and how we may retool certain civilian industries to provide war support. The reason we bring this model up is not to try to explain in detail what all of this looks like, but simply to say that this is a large and complex undertaking even when simplified. What we are going to focus on today are the tactical-level effects on Army.

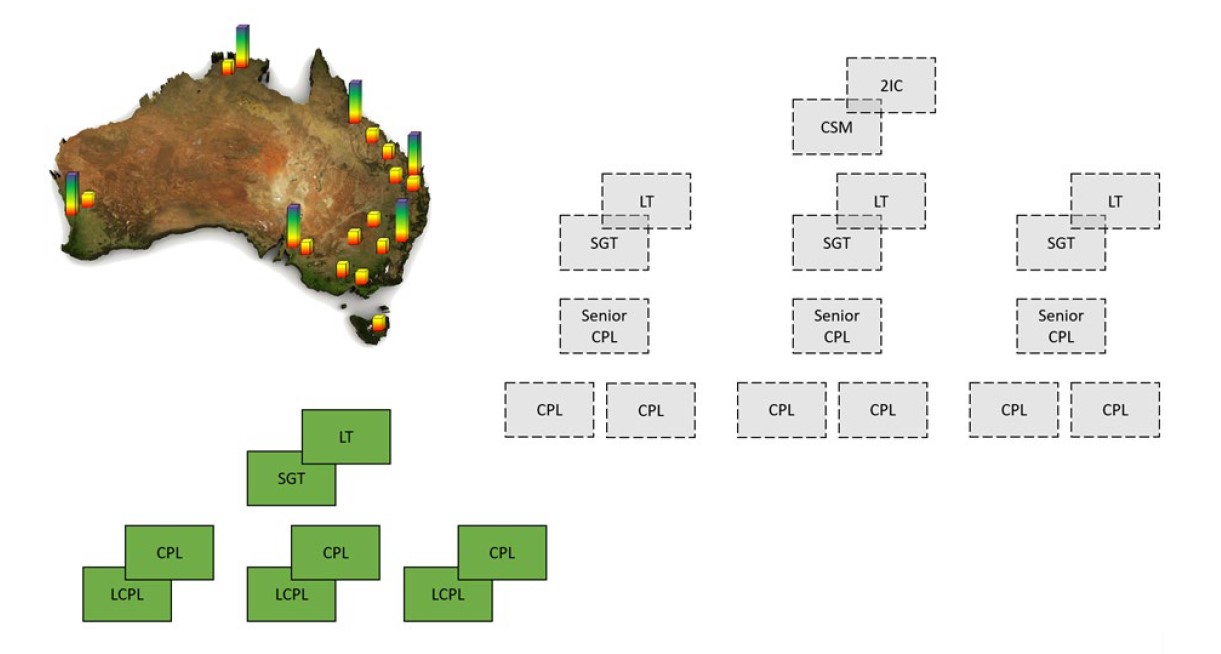

[DAVID CALIGARI]: We will focus particularly on the selective and partial end of the mobilisation spectrum. To achieve that, we will show you another model that we have prepared (see Figure 5). This model looks specifically at the use of personnel within the force. In a world where mobilisation stresses the force, as we move up that continuum, personnel will be a critical component. So let us reflect. Australia has a number of major bases that are invaluable now for training and employing forces. Those facilities, the ranges, the armouries et cetera are used to prepare our forces. Fortunately we not only have the large major bases that often have a brigade posted to them but we also have a large number of smaller bases routinely occupied by 2nd Division staff, indicated on this map in a simplified way. You can observe just some of the over 100 locations on the map, but we certainly could not plot them all in a way you would still be able to see. In these smaller bases, there perhaps is not the degree of infrastructure as at the larger ones, but there are still armouries, ranges, lecture rooms and other training facilities, and then as well often there is a cadre staff of full-time personnel. These are places where Reserves frequently go to train. So they are invaluable. If we look now at a generic example about how some of these bases could be used to expand the force, we can start to visualise how that might happen. As you can see, we’ve looked at a platoon headquarters on the left of Figure 5 as a generic entity. It could be an infantry platoon, it could be something else, but for the purpose of this explanation we have outlined a simple platoon headquarters with the leadership of its sections.

Figure 5: Army personnel distribution

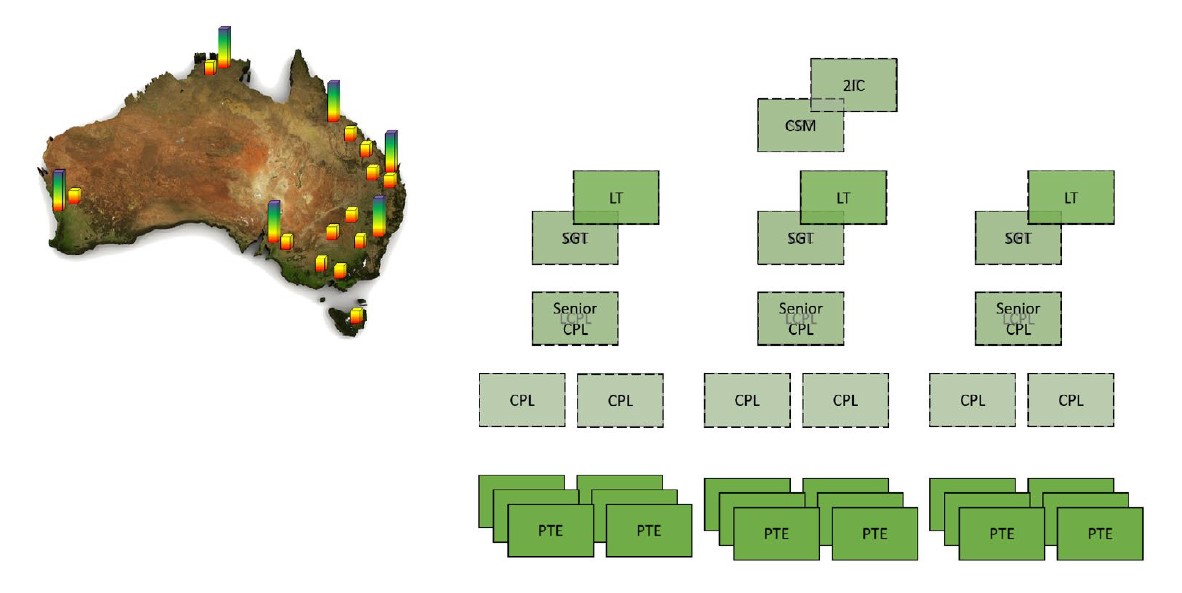

Using this group, we can then expand into a larger organisation, as we might do in the case of a full mobilisation. On the right of Figure 5 is a skeleton for what could be a company headquarters. In an environment where we need to expand the force, the small existing leadership team on the left could be used within that company headquarters but occupy more senior positions, perhaps be promoted or assume roles and responsibilities a little above what they would routinely do (see for example Figure 6). For example, the lieutenant and sergeant could be the company second-in-command and the company sergeant major—thereby forming the nucleus of a company headquarters. The next step is to introduce additional lieutenants from an external pool, or other leaders such as senior non-commissioned officers to fill those officer positions. This demand signal requires increasing the number of lieutenants available to the Army.

Figure 6: Expanded unit based on nucleus existing headquarters personnel

We could look to history as to how this has been done in the past. During the Second World War, the Royal Military College, Duntroon, compressed its course and determined that some elements of training could be done without, and for that reason they were able to draw more quickly on the output of officers. In a contemporary setting, this result could be achieved through any method of creating officers to fill leadership positions. And in fact there are examples of this throughout our history. One of the heroes of my own battalion, Lieutenant Colonel Charlie Green, was removed from Australian staff college early, promoted, and given command of the 3rd Battalion on operations in the Korean War. So there is precedent.

The next step is to grow the mass of our company, comprising the more junior leaders and then the soldiers of that team. To do that, one option is to train new personnel. We could perhaps leverage personnel who have recently separated from the service and who would return while the organisation mobilises, or we could look to other agencies. Perhaps there is a Reserve unit that could contribute those soldiers, or they could be found in related industries such as the police. Regardless, what we see here is a trickle-down of experience and a transfer of skills from those professional leaders that we had placed from the smaller nucleus into this new organisation, who can deliver individual training and then move forward with collective training with whatever time and resources are available to enable the mobilising force to expand—all occurring across the many Reserve bases across Australia. As you can see using this simple example, by using a handful of trained staff, from any part of the professional force (including cadre staff or even existing leaders in Reserve units), we can rapidly expand and train a new much larger fighting organisation. Using this system, we can build a much larger force quickly. Let us now explore the timeline of how this might actually work.

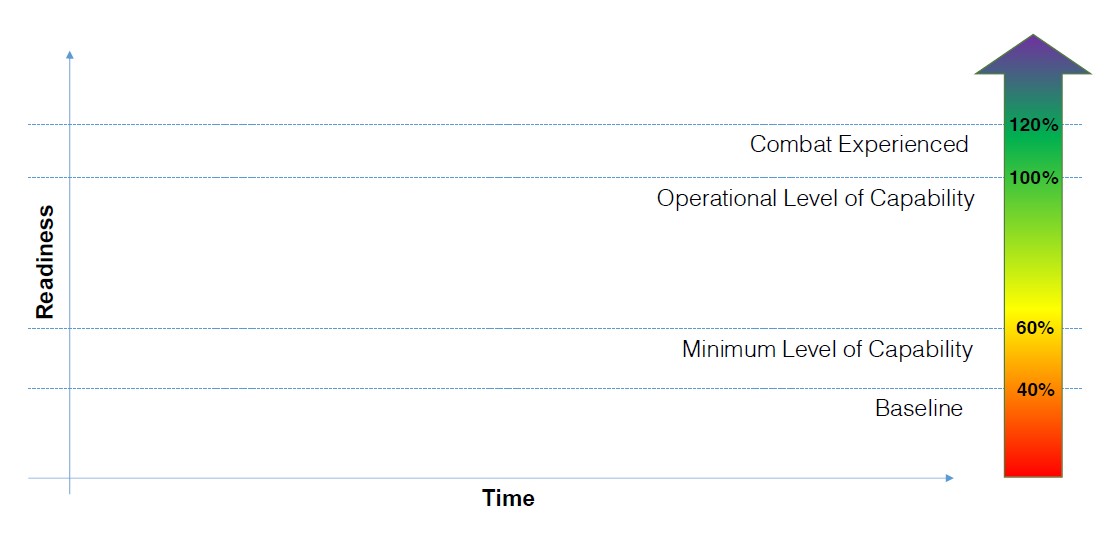

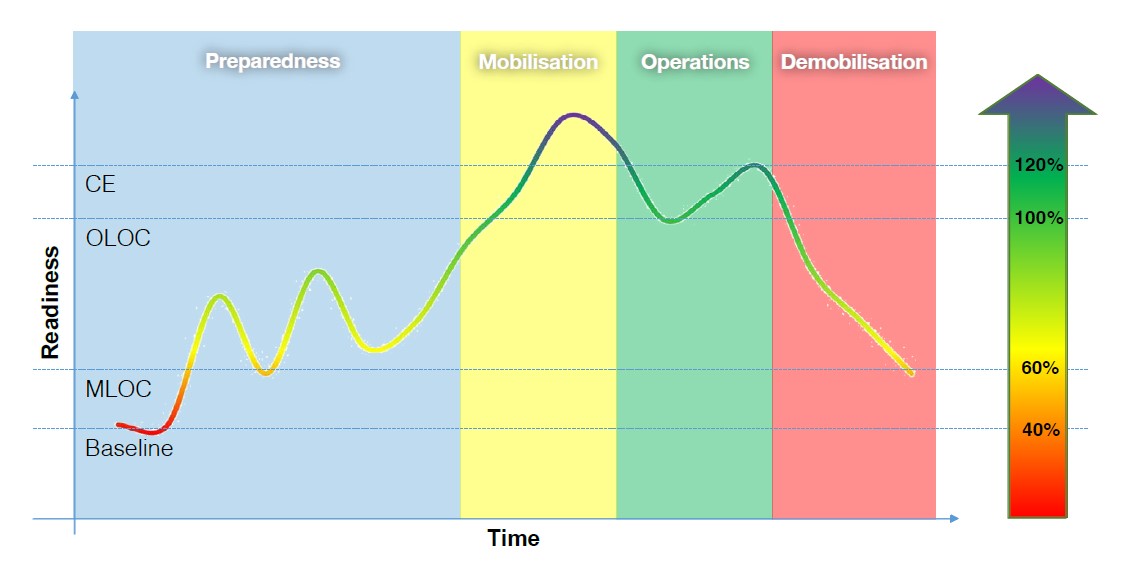

[ZACH LAMBERT]: For most of the people streaming in today, the most interesting part of discussing mobilisation is to talk about how it affects you, or how it affects a specific unit in your situation. We have created a timeline and a model to explain this. If you look at the diagram (Figure 7), you will see on the left an increasing level of readiness. Along the bottom, you’ll see a period of time. On the right hand side, you will see an arbitrary measure of capability.

Figure 7: Readiness levels by time

What that capability looks like is a combination of how much of your force (being personnel and equipment) is available, and a measure of how well trained that force is. It gives an indication of how well we could expect it to perform in combat. For this model, we have allocated that level of baseline readiness at around 40 per cent, which is what you might expect day to day. We have allocated the ‘minimum level of capability’ required to conduct your operational tasking (with significant risks) at around 60 per cent of your entitlement to personnel and equipment. We have then allocated the ‘operational level of capability’ (being what you require to be fully capable of all tasks you can be assigned) at 100 per cent of your personnel and equipment. Anything above this is a consequence of training, good leadership and morale, likely resulting from combat experience.

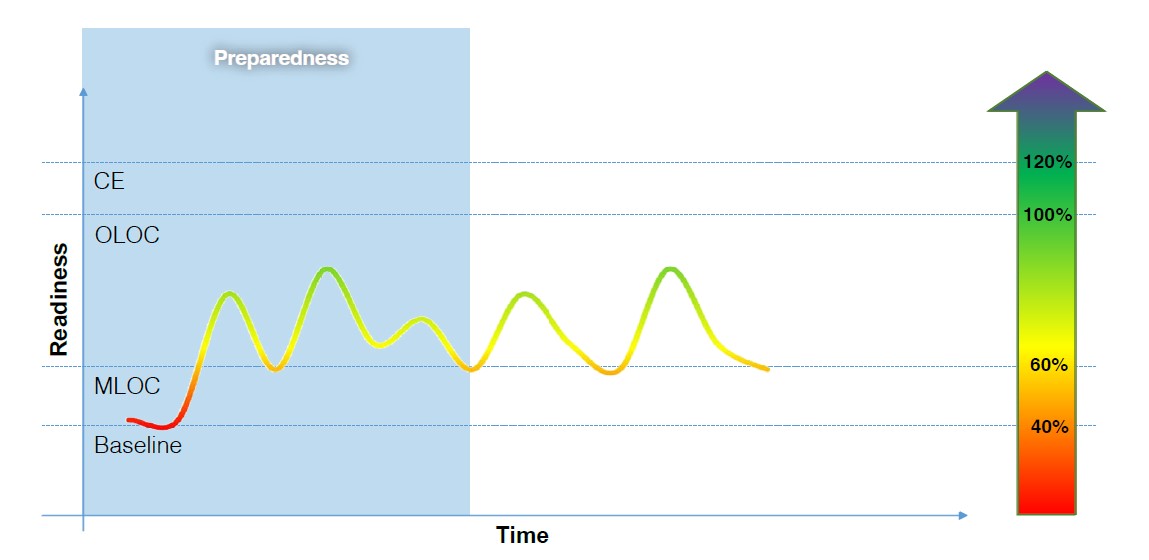

Now we are going to look at this model over the four phases that we introduced right at the very beginning, the first being the preparation phase. A unit in the preparation phase might start out with ‘low’ as their baseline capability, and then continue over time conducting preparedness activities to improve themselves until they are at a higher level of readiness (see Figure 8).

Figure 8: Example unit preparation by over time

This process might go on for an extended period of time, and potentially forever for some units, maintaining that readiness to be tasked for future operations. But we are not here to talk about preparedness. We are here to talk about mobilisation. Therefore, we will look at what happens once a unit has been activated and needs to be put into a position to conduct an activity (see Figure 9). As you can see, as a unit moves into the mobilisation phase its readiness increases as close as possible to its operational level of capability. From there, several activities will be conducted which will improve the unit’s readiness even further. These activities will get you ready to step off to conduct your operational task. As you progress, you are deemed ready and are then moved into operations. During the operation phase, activities will be conducted—potentially including combat operations—and your readiness will degrade as you take casualties or as new tactics and techniques are used against you by your adversary. After a period of time, you’ll develop your own tactics and techniques to counter that, and continue to reconstitute with reinforcements, until you’re performing better.

Figure 9: Example unit operational activity by readiness over time

The final stage (or phase) in this model is demobilisation. In this phase, you can expect that your readiness will decrease quite significantly as you are stood down from the activity that you have been conducting. That might even mean a transfer of your materiel or expertise to another element. At the end of that phase, you then move back into the preparedness phase as you get ready for the next activity. But it is important to note that you retain the knowledge and skills from your mobilisation in the organisation, so preparedness levels overall are higher, which makes future mobilisation activities easier with a more capable force. Now I want to go into more detail with some specific real-world examples, so I will hand over to Dave to cover those.

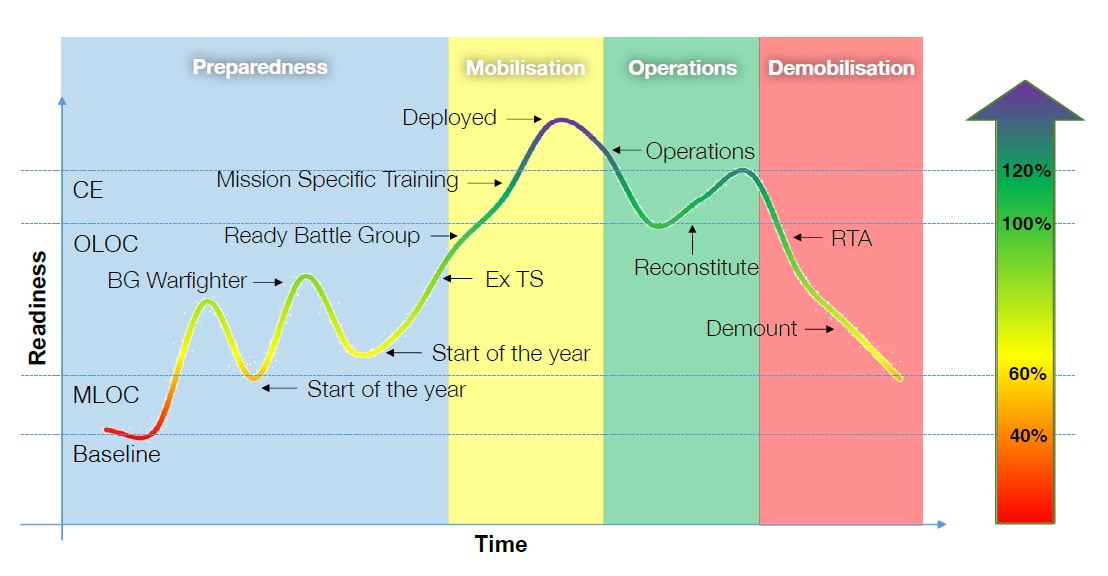

[DAVID CALIGARI]: Let us look again at a simple example (Figure 10) of a unit and consider an infantry battalion for this example. We start the year, as you can see, at about the minimum level of capability. We have just had a posting cycle; perhaps there is a lot of leadership changeover. The battalion needs relationships to form and teams to spend time together—learning to learn to work together effectively. That begins the process of building preparedness. From there, this battalion determines that it has a progression of training goals to accomplish (as every unit would do at the beginning of the year) to build through the Army training levels and standards, including conducting a battle group ‘warfighter’ exercise with the Combat Training Centre. In this case, our example sees them complete their highest level of training during Exercise Talisman Sabre.

Following this exercise, this battalion is at the highest level of readiness. They have now practised everything that they have been rehearsing for the year. If no operational activity is required (as occurs in many battalions), there will then be a requirement to reinvest in individual training to round out the year, and for an infantry unit that may look like an infantry specialist course period. We would also naturally see teams change over during the posting cycle, and at the start of the following year, the unit would likely find itself at a lower level of readiness, but not as low as it started the year before. For example, there could be benefits such as that some of the soldiers participating in infantry specialist courses were previously instructed by junior non-commissioned officers who have now become their section commanders, or perhaps the leadership in some of the company headquarters has not changed significantly. Therefore, you are at a higher standard. From there, the unit goes through the same process it did in the previous year, with the escalation of training moving through Army training levels and standards.

Figure 10: Applied example of unit operational activity by readiness over time

If an operational task was to feature in this timeline, things would be very different. This example unit is quite fortunate, having completed a Combat Training Centre led exercise and a major international exercise, Exercise Talisman Sabre. Once that training has concluded and the higher level of readiness has been achieved through the significant collective training event, the unit is then ready to assume Ready Battle Group responsibilities. Of course, in this simplified example we have removed some of the other factors—not to lessen their importance—like confirming that the standard of training is uniform and that everyone has all of the essential components so that the whole team is ready for Ready Battle Group. Once the battalion assumes the Ready Battle Group function, this begins the mobilisation phase where the team starts to prepare in response to a readiness notice. They know the sorts of tasks they might be employed to undertake as the Ready Battle Group, and this allows them to do mission-specific training. This involves extra training tailored for the sorts of missions they might receive and, importantly, comes with extra resources. There is therefore an increased opportunity for them to prepare, to the operational level of capability. Once they have completed mission-specific training they deploy. They are conducting those operations and, as Zach mentioned, natural attrition and a slight degradation in readiness will occur as casualties and other factors affect the force. Nevertheless, they will learn from the experience.

As a deployed element, the unit will receive reinforcements and have the opportunity to improve their tactics, techniques and procedures as they further increase their understanding of the adversary and environment. They will also go through a reconstitution phase where they increase their readiness. That process continues until the unit completes its operations and finalises its activities. Perhaps another unit will replace it. In this example, the unit will return to Australia and demount. I will reinforce one particular point: while this dismount is occurring, equipment is being handed back rather than being returned to the unit. It is actually more often than not going to a replacement unit (not represented in our chart today), which would be in the mobilisation phase and would be benefiting from that battle-tested equipment. The experience that this original team gained from its operation would likely improve the transfer of skills and knowledge. This represents an extra factor that helps replacement units get above the operational of level of capability and improves their combat experience. So there are mobilisation benefits even during the demounting phase.

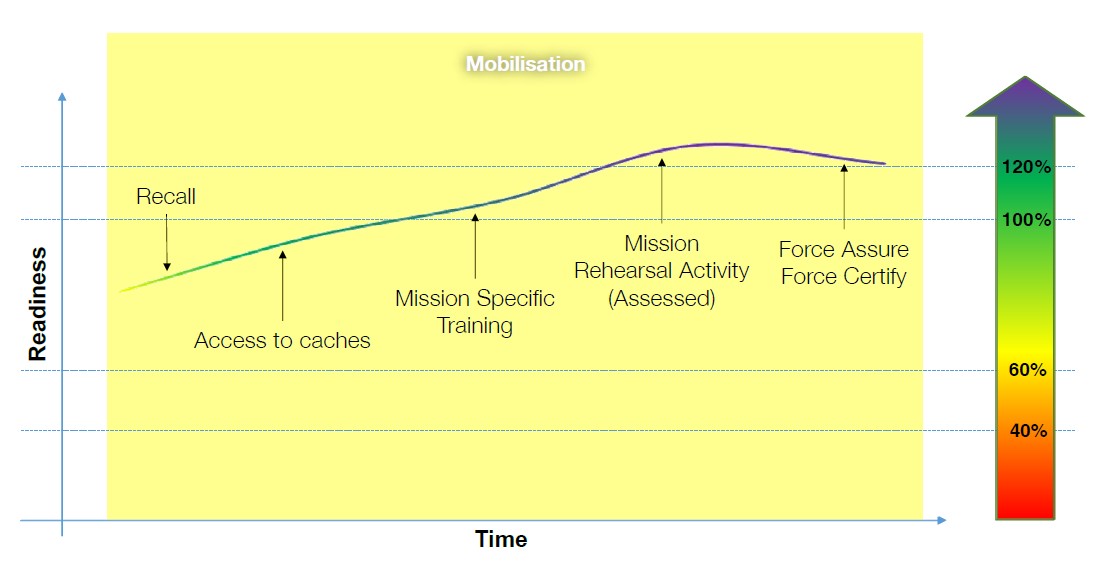

But we’re here to talk about mobilisation, so let us focus on the mobilisation phase in some more detail (see Figure 11). I mentioned mobilisation starts with the readiness notice, which naturally starts with a recall. During the recall the organisation will physically see and account for every person who will participate in the operations to follow. The recall is the first time where everyone is there. It is an opportune moment for a commander to provide some intent and it sets the scene for this busy and eventful phase of mobilisation. After a recall has occurred, the unit may also be provided access to extra specialist equipment caches that are above the resources provided to reach the operational level of capability. For example, live body armour could be cached equipment, and a number of other things such as less-than-lethal ammunition natures (tear gas grenades and baton rounds, for example) above what would normally be allocated each training year. This equipment allocation is useful because it accelerates the unit’s readiness. The next step, and I briefly mentioned it before, is mission-specific training. For our fictional battalion here, this could involve an increased amount of crowd control training, or it could be using those new less-than-lethal ammunition natures that perhaps people were competent on but could improve on their proficiency. It is aspects like these that will increase the performance of the team.

As part of this mission-specific training, they would conduct scenarios informed by analysis from their intelligence cell to improve their training progression and increase performance ready for operations. Once that training has occurred, it is often important to do a mission rehearsal activity. Here, the gold standard is usually the allocation of an external assessor who brings in additional resources to assess a ‘full mission profile’ or mission-specific training activity (as realistic as possible) to truly test the unit, in conditions that are as close as is achievable to the environment in which they will be operating. This is important. Once the activity has been completed, and any remediation has occurred, the team is at its highest level of readiness to deploy. This is an opportune moment for a commander to ‘force assure’ that everything has been done to best prepare the forces. A functional-level commander, such as an officer in charge of a division-size element, then certifies the force, which means he or she is comfortable that the team can deploy. So that explains more detail on the mobilisation phase for a unit. I will now hand over to Zach to discuss a little more about the resourcing required to enable that process.

Figure 11: Mobilisation phase activities

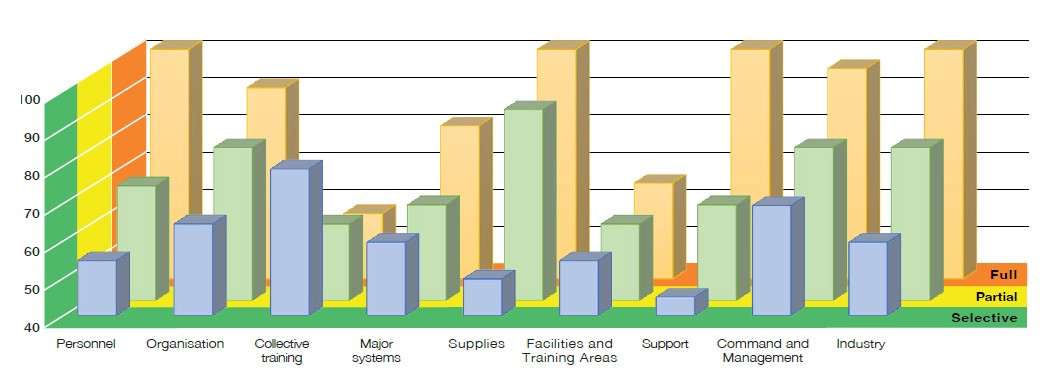

[ZACH LAMBERT]: Mobilisation is inherently a resource-intensive activity. There are a bunch of ways for us to consider the resource requirements for mobilising, but one of the easier and more upfront ways is to use the fundamental inputs to capability (FIC). Most of you will be at least somewhat familiar with these capabilities from Army’s ‘raise, train, sustain’ function, and these are the resource inputs that we tend to see across the organisation. In mobilisation discussions, they are also called the ‘mobilisation factors’. If you have a look at the diagram (Figure 12), you will see (along the bottom) the nine FIC, ranging from personnel through to industry. You’ll also see stacked behind them the three levels of mobilisation that we will be discussing. These are selective, partial, and then full mobilisation.

Figure 12: Fundamental inputs to capability

National mobilisation becomes a complex and externally controlled activity that is reliant on many government-specific interactions, so we are going to leave that one out for this particular discussion. Firstly, having a look at the selective mobilisation, you are not going to have everything, and in fact some FIC are going to be at quite low levels. But you will have certain things. For example, you might be sitting at 60 to 70 per cent of your personnel and have a similar amount of your platforms available to you. But what you will be able to guarantee is a high level of collective training because we can really focus on those selected units that are going on operations. Areas that you might have more challenges in include supply and support, particularly maintenance and specialty support, to enable your selective mobilisation. That’s because these are always tasked over an extremely broad base of activities that are occurring simultaneously. Now, when we advance towards a partial mobilisation, you can see that some things have changed here. For example, you can see a fairly significant increase in personnel as we weight our effort towards operations and achieve increases in support from industry as they start to recognise that they can step in and assist us by providing solutions. You will also note that some areas will drop or remain fairly stagnant. For example, collective training is likely to be less available as more and more units require it, and facilities and training areas are likely to remain constant, as these are not things that we can significantly improve at short notice. Overall, you can expect that areas like command and management (using our currently in-place systems) will improve in efficiency and level of support provided.

Our organisational ability to manage these things will start increasing as we continue to mobilise. That might look like, for example, the provision of joint force headquarters to coordinate these activities. Finally, when we move towards full mobilisation, you can see many things will increase as we can start to tap into the Australian support base. This includes, for example, a real focus from industry on supporting our operations because it is in their best interests for us to defend Australia’s interests. You can also see a dramatic increase in support as we start to bring new capabilities online and bring people back into the ADF to provide support that would otherwise be quite difficult to retain, such as doctors. You will also see quite a significant increase in personnel as we commit almost all, if not all, of the forces that Australia has towards this endeavour. This model just gives you a simplified concept of how we would likely gain the resources that we need as part of mobilisation activities. From here, we would like to finish up by going through some of the challenges that we face. There are three key challenges we would like to speak about (shown in brief at Figure 13).

Figure 13: Challenges experienced during mobilisation

The first is shortages. During the COVID-19 pandemic, we all saw the impact of supply shortages on our families. The ADF is not immune to these supply shortages, particularly with fuel and ammunition. Mobilisation will require expansion to the volume of supplies we might need. There are smart people in industry and government who are working on these problems right now.

[DAVID CALIGARI]: Another aspect of potential shortages is the availability of platforms. As we know, there are a finite number of platforms in the ADF and some of them do not currently feature on any production line, should we need them quickly. For example, some of the future vehicles being brought into service offer fantastic capability but are not yet being produced or are being produced in limited numbers, and that could create shortages.

The second challenge is scaling, should we need to expand the force. We need the command and control systems, or our headquarters units, to be in place to lead and manage our new team, or our expanding team. Fortunately Army is addressing this with the reinforcement of the 2nd Division. This provides a baseline framework for scaling and is a great start. However, the other side of the coin is hollowness.

[ZACH LAMBERT]: We have all seen the impacts of hollowness, particularly over the last few years. Hollowness means incomplete teams, and incomplete teams make it harder for us to mobilise. Measures to address hollowness require people to be removed from other teams to make a whole—to fill gaps. This results in individuals having to re-form teams and spend less time with their teams and, as a result, generates a lower level of overall readiness.

The third challenge is risk acceptance. Aversion to governance risk is a major challenge in expanding the force rapidly. As we expand our use of supplies, we will experience a degree of wastage. We must develop a tolerance for the governance risk this represents, within reason. This includes reducing red tape wherever possible.

[DAVID CALIGARI]: The last aspect of mobilisation worth discussing is that, as we stress the force within the stages of mobilisation, there may come a time at which we need to compromise on some things. Commanders will need to select options that are not perfect. This compromise may increase governance risk, but we need to be comfortable making these choices. Australia has a tradition of successfully mobilising forces when they are needed. We have explained that and shown it. Army is well placed to continue supporting operations and building contingency forces. Your chance to be part of this journey may not be too far around the corner.

That concludes our discussion on mobilisation. We hope you have taken something away. We’d now like to take questions.

[QUESTION]: During the mobilisation phase, you have outlined the requirement for mission-specific training, and mission rehearsal exercises. What base period would this be completed over, and could elements of this be achieved during the prep phase, or do you see elements of being able to achieve some of these during the prep phase?

[DAVID CALIGARI]: That’s a great question. I have found it to be the case that every unit in Army is keen to do everything that they can to be prepared for whatever may arise. Because of that interest and focus, more often than not they will be doing things as early as they are able to. The benefit is that whatever you can do now will save you time later. I am certain that there will always be opportunities for units to do things that are likely to be important in the future so that they can save space for the unexpected. For example, an important skill set that we’ve seen in recent history is crowd control. It takes some time to develop sufficient skills to be effective at crowd control, because it is about mass and needs a large number of soldiers and officers. The journey could be started earlier than the mobilisation phase and it needs to start earlier; so that is an example of something that could be done—and is often done—very well.

[ZACH LAMBERT]: There is an aspect of culture to this too. If you can generate a good readiness culture in your unit, you can shortcut many of these issues. However, you just have to be careful that you do not overstep the readiness notices that are provided to us by our higher headquarters. The reason for that is there are only so many resources across the organisation and there’s only so much time and there are only so many soldiers and we can’t afford to burn our guys out by over-preparing. So this has to be really clear conversation between the units and headquarters.

[QUESTION]: You spoke about how a unit might go from the preparation phase to the mobilisation phase but it was not clear what the triggers might be for that to occur. So how does a unit go from preparation to mobilisation for an activity?

[DAVID CALIGARI]: In the framework we described, the triggers would be apparent before entering mobilisation, and would likely come as orders from headquarters. To continue the Ready Battle Group concept, when a battalion or a unit assumes a responsibility to perform this role, there would be a mounting directive or an order coming from ‘higher’. In our instance, that might come from the highest levels—being the Chief of Joint Operations, on behalf of the CDF. There is often sufficient time to understand that mobilisation is coming and there is usually a date, and a notice to move, introduced as part of the orders. It would go from Joint Operations Command Headquarters down through Headquarters 1st Division, through the formations and to the battalion. The benefit of this system is that, because the Ready Battle Group is an organisation that includes number of different personnel from different formations and battalions, there is an opportunity as the orders trickle down to bring together the team and to set the date when they will force concentrate to commence their preparation.

[ZACH LAMBERT]: It is also important to note that this direction does not just come from nowhere. Government needs to provide direction for any of these activities, and to provide that direction to the ADF to act. Once that direction has been provided, we then go through this process; and we do have specific forces on specific notices to move as per the direction from the CDF—based on the guidance he receives from government—to act at relatively short notice.

[QUESTION]: For a unit that is not the Ready Battle Group but may want to be ready to take on short-notice tasks that might be available, what sorts of things can a non-Ready Battle Group unit do to improve their readiness outside of being assigned as a specific contingency force element?

[ZACH LAMBERT]: This links back to my previous comments about culture. You can create a culture of activity before you actually need to start mobilising. At the lowest levels, this is as simple as making sure that your ‘Deployment Preparation One’ (known by our soldiers as DP1) checks are correct, that your vehicles are correctly managed and maintained, that your skill sets are in place, and that your family situation supports you being away for long periods of time at short notice. I think all these things combine to put you in a position where your chain of command can then focus on the training that will really help you, and increase your ability (within resource constraints) before you are even selected for an activity. It is also important to stay up to date, particularly with situational awareness of strategic hotspots and intelligence. I know that this is a particular issue now that the brigades are allocated to specific geographic areas, and we are trying to address this situation by letting our intelligence cells focus and create better linkages to our higher headquarters to pass that information down as well.

[DAVID CALIGARI]: The hardest part of this journey is the final 1 to 2 per cent. This is because we seek the most complete teams and we want to have all of the training that is needed for all of the members as well. This is in addition to all of the other gateways to deploying we must pass through to be an optimally ready team. It is important to focus on ensuring that those requirements are met as early as you are able. For example, Army is implementing training, much of which is fantastic, in areas such as the ‘Army Combatives Program’, enhanced combat shooting and other programs. There is a need to continuously confirm that everyone has the qualifications they need to fill the roles that may require those skills. Unfortunately, we continue to find that, sometimes unexpectedly, some members do not yet have those qualifications. So if you are able to get that last couple of per cent of the large group ready, and every person has achieved precision in the skill sets required, that will pay the biggest dividend later. We must not forget, though, when the mission starts, you take the team you’ve got with whatever skills and qualifications the deploying commander assesses are necessary. We must never let the 100 per cent stop us from doing our job, and the deploying commander is the best judge of that risk.

[QUESTION]: You mentioned that collective training would not be as high during partial mobilisation as it is during selective mobilisation. Why do collective training levels drop just because forces are being more mobilised?

[ZACH LAMBERT]: This one comes down to resources in the end. We only have so many resources allocated to our collective training agencies. There’s only so much a brigade headquarters can do when it’s starting to try to raise forces before they go off, while also conducting its primary role of raise, train and sustain. When it comes down to it, the standard across the board will not be allowed to drop, but the volume of collective training might have to. For example, instead of a mission-ready exercise or mission-ready activity that goes for a month, we might only be able to afford a laser-focused week with a particular group. I feel as though that will put us in a position where we’re doing the best we can with the limited resources we have, and it will improve over time. But there will certainly be a degradation as we move up in mobilisation intensity across those stages in the overall volume of collective training that is able to be conducted.