Overseas Plan 401 and the Interwar Australian Military Forces (1919–1939)

One thing alone is of import: the point of preparation reached at the actual outbreak of war.—Ferdinand Foch[1]

One thing alone is of import: the point of preparation reached at the actual outbreak of war.—Ferdinand Foch[1]

It is conceivable that the Australian Defence Force (ADF) may, within coming years, be called upon by the Australian Government and people to raise, train, sustain, and deploy an expeditionary force into the Indo-Pacific littoral.[2] Scenarios for such a contingency are easy to imagine, and could include a great power conflict between China and a multinational coalition led by the United States of America (USA), or a forward deployment of Australian military power to secure the integrity of Australian or an international partner’s sovereign territory from a regional competitor.[3] Such a deployment could be beyond anything contemplated for decades, and dwarf—in both scale and risk—Australia’s contributions to conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, or its peacekeeping operations in Timor-Leste or the Solomon Islands. Task-organised battle groups, built around a particular sub-unit or battalion, may not meet the scale required. Instead, the government of the day may have to consider a larger deployment—a rotation of brigades or an entire division or divisions, supported by appropriate enablers, with replacements and reinforcements as required.

With sufficient planning and lead time, such a deployment is neither outside the capability of the ADF nor inconsistent with its history. Since its birth in 1901, the Australian Army has mobilised and deployed combat-capable forces to Southern Africa, North Africa, the Middle East, North, Central, and South-East Asia, and Oceania. Yet not since the Vietnam War has Army deployed a brigade-sized unit into major combat operations overseas, and not since the Second World War has it deployed a division. The mobilisation and despatch of such forces is a complex process. Writing in 1883, the British Army’s Lieutenant Colonel George Armand Furse argued that a ‘carefully detailed plan of action’ was required, and that it:

should contain full instructions on all points that require to be generally known; it should take in the smallest details, and should show the place of assembly of the personnel belonging to each part of the force; the sources from which the officers, men, horses, and materiel required to complete the corps to war strength are to be obtained; the partition of the work, the time allotted to each operation, and the gradual completion of the whole. All officers alike should be acquainted with its main features, and the order to mobilise should suffice to commence the operations, no further directions being needed.[4]

History is replete with inspiration and insight to guide contemporary mobilisation and expeditionary force planning, and Army can look to its own past for relevant examples.

On 15 September 1939, 12 days after Australia declared war on Nazi Germany, Prime Minister Robert Menzies announced the formation of a ‘special force’ of 20,000 men, organised into a division, for ‘service at home or abroad’.[5] This declaration did not catch the Australian Army flatfooted. Since 1922 Army had developed, maintained, updated, and amended detailed plans to mobilise expeditionary forces of varying sizes and capabilities for service overseas. Over the weeks and months that followed Menzies’ statement, Army enacted this plan—titled Overseas Plan 401—to raise what would become the 6th Australian Infantry Division of the Second Australian Imperial Force (2nd AIF). While the formation and war history of this division and the 2nd AIF has already been explored in detail elsewhere, what has not been examined is the planning process through which this critical plan was developed and evolved in the years before it was enacted.[6] It is altogether surprising that Overseas Plan 401 has received little academic analysis to date. No mention of the plan is contained in the Second World War Official History series (Australia in the War of 1939–1945), including within Gavin Long’s first volume, To Benghazi, which discusses the interwar period and the raising of the 2nd AIF in depth.[7] As this article will show, subsequent claims by historians regarding the plan (such as that it was ‘prepared in 1922’, or ‘dusted off’ for implementation in 1939) lack the nuance born from engagement with the substantial, albeit incomplete, archival material available.[8]

This article examines the context and development of Overseas Plan 401 up to its implementation in September and October 1939. It contextualises the planning process both within Australia’s history of expeditionary force operations to the interwar period, and within the period itself. The article analyses the genesis and development of the plan from its earliest iteration as the ‘STAR’ plan, through to its codification in 1924, and it discusses the differing conceptions of how such a plan could or would be used. The key features of Overseas Plan 401, and the subordinate plans for enacting it as developed by the state-centred Military District Base Headquarters, are also explored.[9] The article then surveys subsequent updates and revisions, including a substantial revision in 1931–1934 and a flurry of amendments in 1938–1939. Implementation of Overseas Plan 401 (that is, the raising of 6th Division) has already been discussed elsewhere, but several key challenges in effecting the plan are outlined to highlight its deficiencies. The article’s conclusion then highlights key lessons from the planning process that have enduring relevance to a contemporary audience. Understanding the strengths and weaknesses of Overseas Plan 401 offers much food for thought, both for those undertaking expeditionary force or mobilisation planning and for those who may expect to be drawn into such spheres in coming years.

Endnotes

[1] Ferdinand Foch, The Principles of War, trans. Hilaire Belloc (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1920), p. 44.

[2] The author would like to thank Dr Andrew Richardson, Dr John Nash, Ms Luisa Powell, COL Anthony Duus, and Ms Hannah Woodford-Smith for their encouragement in producing this article. As always, this piece would not have been possible without the support of Mrs Renee Beavis, and the distractions offered by Miss Cassandra Beavis.

[3] For a range of potential contingencies, see Andrew Carr and Stephan Frühling, Forward Presence for Deterrence: Implications for the Australian Army (Canberra: Australian Army Research Centre, 2023).

[4] Italics in original. George Armand Furse, Mobilisation and Embarkation of an Army Corps (London: William Clowes and Sons, 1883), p. 7.

[5] ‘Big Rush of Volunteers to Join Special Force’, The Telegraph (Brisbane, QLD), 16 September 1939, p. 1.

[6] See, for example, Gavin Long, To Benghazi (Canberra: Australian War Memorial, 1961); Mark Johnston, The Proud 6th: An Illustrated History of the 6th Australian Division 1939–1946 (Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 2008); Craig Stockings, Bardia: Myth, Reality and the Heirs of ANZAC (Sydney: UNSW Press, 2009); and Peter J Dean, The Architect of Victory: The Military Career of Lieutenant-General Sir Frank Horton Berryman (Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 2011).

[7] Long, To Benghazi.

[8] David Horner, Strategy and Command: Issues in Australia’s Twentieth-Century Wars (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022), p. 77; John Blaxland, Strategic Cousins: Australian and Canadian Expeditionary Forces and the British and American Empires (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2006), p. 62.

[9] In the interwar period Australia was divided into seven military districts, roughly analogous with each of the states. The districts were as follows: 1st Military District—Queensland; 2nd Military District—New South Wales; 3rd Military District—Victoria; 4th Military District—South Australia; 5th Military District—Western Australia; and 6th Military District—Hobart.

By the dawn of the interwar period in 1919, Australia and its precursor colonies had already developed significant experience and expertise in the mobilisation and deployment of expeditionary forces abroad. In March 1885, a force of 770 infantry and artillerymen were raised in colonial New South Wales and despatched to the Sudan, a three-month deployment supporting a British campaign to reassert control over the area.[10] Fourteen years later, the Australian colonies again rallied to support a British imperial campaign. Between 1899 and 1902, some 16,175 personnel—first in colonial contingents and later in federated Australian contingents—were deployed to Southern Africa against the Boers of the Transvaal Republic and the Orange Free State.[11] At the time, they were regarded as ‘more imperial volunteers than Australian soldiers’; sent overseas as individual battalions or regiments, the units and personnel were integrated within British formations and operated under the strategic and operational command of British officers, subordinate to their authority and reliant upon them for sustainment.[12]

In the aftermath of the South African War, the newly formed Australian Army remained cognisant of the potential need to mobilise and deploy a force abroad to support the defence of the empire and the nation. Realising this requirement, however, was rendered difficult due to Army’s legislative basis under the Defence Act 1903, which specified that:

Members of the Defence Force who are members of the Military Forces shall not be required, unless they voluntarily agree to do so, to serve beyond the limits of the Commonwealth and those of any Territory under the authority of the Commonwealth.[13]

Despite this principle, Australian and British politicians and soldiers continued to acknowledge a role in a future conflict for Australian troops.[14] In a May 1911 memorandum, for example, the British Army’s General Staff in the War Office suggested that, in a hypothetical crisis in Egypt, Australian forces might not arrive in time to ‘take part in a decisive action, but reinforcements from India might do so provided they started in anticipation of relief by troops coming from the Commonwealth’.[15] The Australian Government therefore needed to consider the amount and nature of assistance they would be prepared to offer so that ‘definite plans of action’ could be prepared.[16] During the 1911 Imperial Conference in London, Australia’s Minister for Defence, George Pearce, agreed to instruct Army Headquarters (AHQ) to secretly commence detailed planning for a future expeditionary force.[17] Such planning was leant an even more imperial flavour following a November 1912 conference between Pearce; the Australian Chief of the General Staff (CGS(A)), Brigadier General Joseph Gordon; and the General Officer Commanding the New Zealand Military Forces (GOC(NZ)), Major General Alexander Godley. Here they agreed that:

at any time that it is deemed advisable to contribute a quota to an Imperial expeditionary force the Commonwealth and the Dominion should make a joint contribution in the form of an Australasian division, or, as an alternative, an Australasian mounted force.[18]

Over the subsequent 20 months, some progress was made in planning for an expeditionary force, with a draft plan more akin to a ‘study’ developed to raise 12,000 troops for overseas deployment.[19]

In August 1914 the ‘pattern of imperial assistance’ to Britain’s wars, established in the Sudan and the South African War, was repeated on a larger scale.[20] Within a fortnight of the declaration of war upon imperial Germany, the Australian Army had begun to raise two separate forces for action overseas. In response to a request from the British Government on 6 August 1914 to capture German possessions in New Guinea, an Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force (AN&MEF) of six companies of the Royal Australian Naval Reserve, an infantry battalion, two machine gun sections, a signalling section and a Medical Corps detachment was concentrated in Sydney. Within a week, the force was organised, clothed, armed, and given some rudimentary training before embarking on 18 August 1914, whereafter it spent the next four months successfully capturing German territory.[21] The second force, comprising the 1st Australian Division as the Australian Imperial Force (AIF), needs little introduction or description as its mobilisation, expansion, and campaigns have been the source of significant academic exploration.[22] Yet it is worth noting that the 1st Australian Division was the first such formation raised within Australia, recruited on the basis of a quota system whereby the most populated states provided the highest portion of troops, and it was ‘mobilised in the remarkably short time of six weeks’, with preferential recruiting of veteran or semi-trained manpower meaning that of the 14,693 enlistees some 58.49 per cent had served previously in the Citizen Forces or the British Army (regular or territorial).[23] During the First World War, the AIF would ultimately reach a strength of five infantry divisions under an Australian Corps headquarters, and almost two cavalry divisions. Although it started from a very low competency and experience base, through hard training and battlefield exposure the AIF became an effective force that directly contributed to the Allied victory.

[10] Jeffrey Grey, A Military History of Australia, 3rd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), p. 49.

[11] Ibid., p. 57.

[12] Craig Wilcox, ‘Looking Back on the South African War’ (presentation, Chief of Army History Conference, Canberra, 1999).

[13] Defence Act 1903, article 49, at: https://www.legislation.gov.au/C1903A00020/asmade/text.

[14] See John Mordike, An Army for a Nation (North Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1992).

[15] The War Office was the department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army, and simultaneously headquarters of the British Army. It was located in Whitehall, London.

[16] [British Army] General Staff, ‘The Co-operation of the Military Forces of the Empire’, 12 May 1911, National Archives of Australia (NAA): A5954, 1185/5, 693755.

[17] Mordike, An Army for a Nation, pp. 243–244.

[18] ‘Proceedings of the Conference between MAJOR-GENERAL A.J.GODLEY, C.B., Commanding New Zealand Military Forces, and BRIGADIER-GENERAL J.M. GORDON, C.B., Chief of the General Staff, C. M. Forces’, 18 November 1912, NAA: MP84/1, 1586/1/33, 329574.

[19] Ian Bell, Australian Army Mobilisation in 1914 (Canberra: Australian Army History Unit, 2016), p. 23; ‘Questions from HISTORIAN to General White’, 1 October 1919, NAA: A6006, 1914/8/23, 426392.

[20] Keith Jeffery, ‘The Imperial Conference, the Committee of Imperial Defence and the Continental Commitment’, in Peter Dennis and Jeffrey Grey (eds), 1911: Preliminary Moves (Moss Vale: Big Sky Publishing, 2011), p. 39.

[21] The AN&MEF remained in New Guinea territory undertaking occupation duties for the duration of the conflict. See George Pearce, Report by the Minister of State for Defence on the Military Occupation of the German New Guinea Possessions, 10 October 1921 (Melbourne: Commonwealth of Australia), pp. 3–4.

[22] For an excellent overarching analysis of the AIF as an institution, see Jean Bou and Peter Dennis, with Paul Dalgleish, The Australian Imperial Force (South Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 2016).

[23] Robert Stevenson, ‘The Forgotten First: The 1st Australian Division in the Great War and its Legacy’, Australian Army Journal IV, no. 1 (2007): 188; Bell, Australian Army Mobilisation in 1914, p. 60.

In the aftermath of the First World War, both Army and the nation swiftly demobilised. Yet even before the force was formally disbanded on 31 March 1921, the policy frameworks that would shape Australian defence and the Army were already developed.[24] Interwar Australia remained a convinced supporter of imperial defence, and sought the maintenance of Britain’s superpower status. As Pearce—again Minister for Defence—argued in 1933, ‘Australia’s Defence Policy must be to co-operate in the Imperial Defence Policy and to provide the maximum contribution she can afford to the Defence Forces of the Empire’.[25] Yet such contributions were given through the guise of local defence. The threat of Japan, real or imagined, dominated the consciousness of both politicians and military personnel, and throughout the period successive governments placed their faith in a blue-water naval strategy. This was based on the numerical superiority of the Royal Navy over the Imperial Japanese Navy, established as a result of the 1922 Washington Naval Treaty, and the establishment of a naval base at Singapore. Given the relative size of Australia and its limited financial and manpower resources, Australia had little choice except to rely on the security provided by its membership of the British Empire/Commonwealth, while still seeking to influence British policy and exercise its own agency within the imperial relationship.

This defence policy, whereby local defence was prioritised but an imperial role was acknowledged, was reflected in the Army’s policy framework as established in 1919–1920. Two separate committees were appointed by Pearce in 1919 and 1920 to report on matters of policy and develop practical proposals to guide the structure and training of the postwar Army. The Swinburne Committee sat in June 1919 and recommended the continuation of the prewar citizen-soldier army, permanently organised into divisions and recruited through a universal training scheme.[26] The second committee was labelled a ‘Conference of Senior Officers of the Australian Military Forces’. This conference confirmed the suggestions of the Swinburne Committee and recommended the adoption of an army structure of two cavalry divisions, four infantry divisions, and three mixed brigades capable of forming a fifth division. Importantly, it also suggested the establishment of a munitions supply branch, modernisation of coastal defences, a financial provision to support the training of commanders and staffs, and the establishment of an instructional staff to train non-commissioned personnel. Importantly, the conference also recommended revisions to the voluntary overseas service principle in the Defence Act 1903 to ‘compel service abroad’, arguing that:

[the] community must make up its mind, however unwillingly, that all preparations for the defence of Australia … may break down absolutely if, at a final and decisive moment, the weapon of defence cannot be transferred beyond our territorial waters.[27]

No such revision of the Defence Act occurred, partly due to a postwar ‘myth of an intrinsic Australian aptitude for soldiering’ and that ‘not even the lessons of the Great War … educated public opinion to the degree necessary even to contemplate change of this law’.[28] As a result, the Army remained ‘essentially a territorial defence force, just as the body that existed before World War I had been’,[29] requiring any further overseas force to be raised from scratch, as the AIF had been. The bulk of the conference’s recommendations were accepted and enacted by the government of Prime Minister ‘Billy’ Hughes, though it did reject a significantly increased training period for citizen-soldiers. The form of the Army developed by the conference would be maintained throughout the interwar period, with the important corollaries that in 1922 the citizen force’s establishments were lowered into that of a ‘nucleus’ organisation, and in 1929 the government of Prime Minister James Scullin (1929–1931) abolished the compulsory military training scheme and rendered the citizen-army a volunteer ‘Militia’.

Most post-war Australian governments accepted the possibility of another military contribution to an overseas war involving the British Empire. For example, the coalition governments of Prime Minister Stanley Bruce and Earle Page (1923–1929) specified that the Army was to retain an organisation that could be mobilised both for service in Australia and abroad. While it acknowledged that time, personnel and materiel would be required to prepare it for war service, however, it nevertheless made little provision for such.[30] While the policy lapsed under the government of Prime Minister Scullin (a ‘sincere pacifist’ according to Gavin Long), it was revived under the administration of United Australia Party (UAP) Prime Minister Joseph Lyons. In 1932, UAP Deputy Leader John Latham noted that government policy was for the Army to be ‘capable of operating overseas in the largest possible numbers’.[31] This sentiment was reinforced in 1934 by Pearce (a member of the UAP government) during a meeting in New Zealand when he observed that it was ‘the policy of the Commonwealth Government’ to be able to despatch an expeditionary force of a division overseas within three months of a call to arms, with this to then be followed by ‘a second, and ultimately a third Division’.[32] Despite their prevalence within government circles, such views were always expressed behind closed doors and not uttered in public. No interwar Australian government wished it to be known that preparations were in hand and that discussions had occurred with British and New Zealand officials on such matters. Anti-expeditionary sentiment was strong within the Labor Caucus, and their platform in the lead-up to the 1937 election included a proposal to amend the Defence Act to ‘forbid the raising of forces for service outside Australia, or promise of participation in any future overseas war, except by decision of the people’.[33] Indeed, in organising Australian representation at an upcoming Pacific defence conference in New Zealand, Minister for Defence Geoffrey Street stated that any potential discussion of naval, military or air forces serving overseas was ‘a question of high political importance on which the decision is reserved to the Government’, which could not ‘relax its rigid control even of the discussion of this subject … [owing to] the attitude of a large section of public opinion towards overseas military service’.[34]

Such restrictions and public attitudes did not prevent politicians and servicemen, in both Britain and Australia, hypothesising about how a post-First World War Australian expeditionary force could be used. In a ‘handbook’ prepared in May 1921 (just prior to the Imperial Conference that assembled in London), the British War Office suggested that Australia should ‘be able to maintain at full strength during a long war for the purposes of Imperial defence as a whole’ approximately four divisions. Such forces, they continued, would be of most value in ‘areas comparatively accessible to them, but remote from Great Britain’, with participation and contingents welcome in both ‘small’ and large wars.[35] In 1922, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George and Secretary of State for the Colonies Winston Churchill actively sought Australian and other Dominion contingents to reinforce British positions in the Chanak crisis, considering them a form of imperial manpower reserve. Throughout the 1920s, expectations remained that Australia, and the other Dominions, would contribute within their spheres of interest in future wars. But the rush to rearm in the 1930s prompted further, and more forceful, considerations of the role an Australian contingent would have in future emergencies. In 1934, Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS) General Sir Archibald Montgomery-Massingberd queried CGS(A) Julius Bruche regarding potential timelines for the despatch of an Australian expeditionary force overseas, including the possibility of the ‘provision at short notice of a specially organised force for service in the Pacific Islands or for garrison duty in the Far East’.[36] Visiting Australia in 1934 to advise on Australian Defence, Committee of Imperial Defence (CID) Secretary Hankey reflected the views of Whitehall and the British service chiefs when he recommended the development of:

an expeditionary force in Australia, which could be sent to co-operate in the protection of the strong points on the front line of Australian defence or to relieve British Forces whose presence was urgently required elsewhere.

Prior to his departure, Colonel Thomas Hutton (General Staff Officer Grade 1 in the Directorate of Military Operations at the War Office) had specifically flagged Singapore or India as potentialities, the latter of which also offered better training facilities.[37] A further suggestion from the British service chiefs came in 1936 when, attempting to undermine or sidestep the voluntary overseas service principle, they recommended the development of ‘small additional forces’ in Australia that could ‘reinforce or garrison important points in the Pacific Area at short notice’.[38] Clearly an Australian expeditionary force role in the Pacific, either reinforcing Singapore or garrisoning other British territories in the area, was a consistent perceived role by British decision-makers.

Within Australia, similar views were held. Throughout the interwar period, Australian political figures avoided discussion of where future expeditionary forces might be deployed. This was the case even in secret discussions. In 1932, Latham stated to the British Chiefs of Staff Sub-Committee of the CID that the Australian Army was to be prepared to fight ‘not only in Australia, but also elsewhere’, and that his government believed that, in an emergency, they should do ‘all that was possible towards helping in the main battle wherever it might be’.[39] Army leaders had more specific ideas, and in keeping with the views of the period most saw the Asia-Pacific as the likely theatre. Both government and military figures, however, remained guided by the assumption that any Australian force deployed overseas would do so as a part of a larger, British-led multinational force. The 1920 ‘Senior Officers Conference’ had identified Japan as the primary threat to Australia, and their suggestions regarding alterations to the volunteer principle should be considered in that light, along with any potential requirements to support a military action coordinated by the League of Nations.[40] As early as 1923, Chauvel identified Singapore as a likely location for the despatch of an Australian contingent, though he did note that this would depend on ‘the state of sea power’ which, given overall British lack of strength in the Pacific, ‘would not inspire the people of Australia to send forth a War Garrison’. In parallel, he acknowledged the likelihood that a force so deployed (especially in haste) would ‘be largely untrained and would require intensive training after arrival’.[41] Just one year later, Australia’s inability to send a division built on ‘Great War’ establishments overseas forced Chauvel to downgrade plans to a ‘Small War’ establishment, rendering any expeditionary force to be ‘designed primarily for a war against an enemy who is not armed and equipped on modern lines … [and] unable to meet a modern enemy on anything approaching equal terms’.[42] Such a force would have been capable of garrison duties only, though it would have still made a valuable contribution to imperial defence by relieving a British force to proceed to the main theatre.

Chauvel maintained his conception of the uses of an expeditionary force during his tenure as Inspector General of the Australian Military Forces and CGS(A), and upon his retirement in 1930 it was passed to his successors.[43] Both Bruche and Lavarack continued to perceive the Asia-Pacific as the most logical area of future deployment. In a 7 August 1934 letter to CIGS Montgomery-Massingberd, Bruche hypothesised possible future taskings. He noted that, within three months, Army could deploy a division-sized force either for additional training overseas, for use in garrison duties, or for use against a poorly trained or equipped enemy. He further acknowledged it might also raise and embark (within 37 days) a smaller, partially trained infantry brigade group which, if local naval superiority was assured, could be deployed:

This is a significant statement of intent, and one for both historians and Army planners to consider given government direction to develop an Army ‘optimised for littoral manoeuvre’.[45] Indeed, Bruche’s scenario directly contradicts a persistent hindsight criticism of the interwar Army, namely that:

[between] 1941 and 1943 the defence of Australia was conducted in the maritime littoral environment to the north of the continent. There is no evidence that operations such as these were considered by Australian defence planners in the interwar period.[46]

It should also prompt contemporary planners to consider how quickly they could forward deploy a similarly sized force into the region. Lavarack’s logic followed that of Bruche, and his gaze remained close to home. Given the looming threat of an aggressive Japan, in 1936 Lavarack noted to CIGS General Sir Cyril Deverell that it was now ‘difficult to visualise conditions’ that would enable the deployment of a force overseas in support of an imperial war, although if local naval security was assured he did not ‘see any great difficulty in sending one of two infantry brigades for garrison duty in the Pacific’.[47] Indeed, Lavarack (or a member of his staff) showed a remarkable prescience, stating in July 1936 to Deverell that, in a future European war, Army might ‘relieve the British Army of some of its commitments in the Far and Middle East’, but even in a war of the ‘greatest magnitude … an Australian Expeditionary Force might never again be despatched as far as Europe’.[48] Army’s view on potential theatres of action remained Pacific focused, obsessed as it was with the threat of a territorially aggressive imperial Japan. Yet such views were for the future, for the time when Army had plans to raise such a force; how Army came to develop such a plan will now be explored.

[24] For a fuller examination of Australia’s defence context in the interwar period, upon which this paragraph is based, see Jordan Beavis, ‘The British Empire, Imperial Defence, and Australia’ in ‘A Networked Army: The Australian Military Forces and the other Armies of the Interwar British Commonwealth (1919–1939)’, PhD thesis, University of Newcastle, July 2021, pp. 40–75; John McCarthy, Australia and Imperial Defence 1918–39: A Study in Air and Sea Power (St Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 1976).

[25] George Pearce, ‘Statement of the Government’s Policy Regarding the Defence of Australia’, 25 September 1933, NAA: A664, 449/401/102, 161472.

[26] George Swinburne, ‘Report on Certain Matters of Defence Policy’, 30 June 1919, NAA: A5954, 1209/7, 694520.

[27] The conference was chaired by Lieutenant General ‘Harry’ Chauvel, and included Lieutenant General Sir John Monash, and Major Generals Sir James McCay, Sir Joseph Hobbs, and Sir Brudenell White. Harry Chauvel, ‘Report on the Military Defence of Australia by a Conference of Senior Officers of the Australian Military Forces’, 6 February 1920, NAA: A5945, 797/1, 273702.

[28] Craig Stockings, ‘There is an idea that the Australian is a born soldier …’, in Craig Stockings (ed.), Zombie Myths of Australian Military History (Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2010), p. 94; ‘Liaison Letter (LL) CGS(A) Major-General Sir Brudenell White to Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS) Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson’, 4 February 1922, Library and Archives Canada (LAC): Department of National Defence (DND) Fonds, R11-2-890-6-E, file 3602, microfilm reel (MR) C-8294.

[29] Albert Palazzo, The Australian Army: A History of its Organization 1901–2001 (Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 2001), p. 101.

[30] ‘Note on Australian Army Policy and Activities for use of Minister of Defence during his forthcoming visit to Ottawa’, 19 June 1928, NAA: A5954, 2390/1, 240390.

[31] Committee of Imperial Defence, ‘The Defence of Australia: Report by the Chiefs of Staff—Appendix II’, 30 August 1932, A5954, 1718/1, 240042.

[32] Maurice Hankey to John Dill, 30 November 1934, The National Archives (UK) (TNA): CAB63/70.

[33] Quoted in Frederick Shedden, ‘A Study in British Commonwealth Co-operation: Chapter 17—Conclusion’ (unpublished manuscript, n.d. [c. 1960s]), p. 18, NAA: A5954, 789/2, 651959.

[34] Geoffrey Street to Joseph Lyons, 27 March 1939, NAA: A816, 11/301/213.

[35] War Office, ‘Handbook dealing with the Military Aspect of Imperial Defence’, May 1921, NAA: A5954, 1776/15, 655708.

[36] Archibald Montgomery-Massingberd to Julius Bruche, 8 June 1934, NAA: 407531, MP729/6, 35/401/659, 407531.

[37] Frederick Shedden, ‘Minutes of the Meeting of the Defence Committee, Held on Monday, 5th November, 1934, and Wednesday, 7th November, 1934—Appendix: Summary of Remarks by Sir Maurice Hankey’, 5/7th November 1934, NAA: AA1972/499, NN, 215039; ‘Note of an informal meeting held at 2, Whitehall Gardens, S.W.1., on the 1st August, 1934’, 1 August 1934, TNA: CAB 63/66.

[38] Chiefs of Staff Sub-Committee of the Committee of Imperial Defence, ‘Draft Memorandum for Mr. Bruce Regarding Australian Co-Operation in Defence’, n.d. [c. June 1936], NAA: A5954, 1024/19, 654012.

[39] Chiefs of Staff Sub-Committee of the Committee of Imperial Defence, ‘The Defence of Australia—Appendix II: Extract from the Minutes of the 103rd Meeting of the Chiefs of Staff Sub-Committee, held on June 2, 1932’, 30 August 1932, NAA: A5954, 1718/1, 240042.

[40] See Chauvel, ‘Report on the Military Defence of Australia’.

[41] Chauvel to Brigadier-General Thomas Blamey, 31 August 1923, AWM: AWM113, MH 1-21, 664704.

[42] Chauvel to the Military Board, ‘Mobilization Preparations: War Establishments to be Utilized’, 5 September 1924, NAA: A2653, 1294 Volume 2, 227652.

[43] The thoughts of Chauvel’s direct successor as CGS(A), Major General Walter Coxen, on this matter are not clear in the archival material available.

[44] Bruche to Montgomery-Massingberd, 8 August 1934, NAA: MP729/6, 35/401/659, 407531.

[45] Commonwealth of Australia, National Defence Strategy (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2024), p. 40.

[46] David Horner, Strategy and Command: Issues in Australia’s Twentieth-Century Wars (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022), pp. 76–77.

[47] John Lavarack to Cyril Deverell, 12 May 1936, NAA: A6828, 2/1936 COPY 1, 338632.

[48] John Lavarack to Cyril Deverell, 21 July 1936, NAA: A6828, 3/1936 COPY 1, 338640.

The AIF had not even been disbanded before the Hughes government was asked by Britain to consider despatching or rerouting a force for service overseas. In June 1920, an uprising in British-occupied Iraq caused the War Office to scramble for reinforcements to send to the area. On 18 September, Britain’s Secretary of State for the Colonies, Lord Milner, forwarded to Australia, New Zealand, and Canada a request for ‘some measure of military assistance’, perhaps through the despatch of a unit to Iraq itself, or to India or Palestine to thereby relieve a British unit to embark for Iraq.[49] Hughes declined, outlining to Governor-General Sir Ronald Munro Ferguson the ‘various reasons … he feels it impossible to take action in the matter’.[50] Such reasons are easy to surmise, including how politically unpopular the deployment of such a contingent would be after years of war and over 60,000 dead—there was little public appetite for further imperial adventures abroad. As events transpired, the uprising was soon repressed and the need for Dominion contingents ebbed.

In the midst of a wide-ranging reorganisation of the Army, it is unsurprising that Milner’s request did not trigger within Army Headquarters the need to develop plans for future expeditionary forces. In January 1921, the Military Board ordered the constitution of an ‘Army Head-Quarters Mobilization Committee’, to be presided over by the Deputy Adjutant General and including representatives of the General Staff and Quartermaster General’s branches, though the extent of its deliberations is unclear.[51] Army’s mobilisation planning was hampered while it awaited receipt from Britain of the post-war revision of the Field Service Regulations (FSR)—Army’s capstone doctrinal document—and potential updates to mobilisation processes outlined within it, and the establishment of an operations directorate within AHQ.[52] When received, the definition of mobilisation contained within the updated FSR 1923 (Provisional)did not differ from that elucidated in the 1909 original, namely that:

Mobilization is the process by which an armed force passes from a peace to a war footing, that is to say, its completion to war establishment in personnel, transport and animals, and the provision of its war outfit.

The regulations did, however, provide further guidance on differences between ‘general’ mobilisation—extending to the naval and air forces—and ‘partial’ mobilisation, which was centred on ‘regular’ forces and may nor may not extend to the calling out of reservists and militiamen.[53] Further encouragement to begin conceptual planning came in May 1921, when the British War Office recommended that the Dominions commence ‘studying and preparing plans’; maintenance of such plans would avoid the ‘delay, inefficiency, and waste of both life and treasure’ involved in improvising an expeditionary force if the need arose.[54] Such suggestions, however, provoked no action by AHQ or Pearce.

It took a further imperial crisis to shock the Army out of its postwar planning stupor. In September 1922, the revanchist Turkish Nationalist movement of Mustafa Kemal ejected a Greek army from Western Anatolia, and began eyeing an advance to re-establish Turkish control over a demilitarised international zone around the Dardanelles as established in the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres. The demilitarised zone was garrisoned by a multinational military force which included British troops located near the city of ‘Chanak’.[55] British Prime Minister Lloyd George opted to remain firm in the face of Turkish revisionism, and on 16 September 1922 Secretary of State for the Colonies Winston Churchill cabled the Dominions seeking their support in the crisis and commenting that ‘the announcement that all or any of the Dominions were prepared to send contingents even of moderate size’ would ‘be a potent factor in preventing actual hostilities’.[56] Hughes received the request with shock and alarm; not only had press reports arrived in Australia of the call to arms ahead of the official request, but he and many others in Australia were also unaware of the situation that provoked the request. While Hughes railed in secret telegrams to London regarding the lack of information and consultation from the British Government regarding the crisis, in public he declared that his government ‘would be prepared, if circumstances required, to send a contingent of Australian troops’, if only to defend the Anzac graves at Gallipoli from potential harm.[57]

The sudden crisis caught Army flatfooted. Since the end of the war, little thought had yet been given to plans or schemes to send abroad an expeditionary force—any ‘excess’ staff capacity that could have done so had been eliminated in early 1922 following defence cuts resulting from the Washington Naval Treaty, when some 69 of the 313 Staff Corps officers in the Army were retrenched.[58] All three branches of AHQ commenced rapid development of plans to raise a contingent for overseas service. Within a fortnight of the initial British request, the General Staff Branch in AHQ forwarded to the district bases sealed packets marked with the code word ‘STAR’, which were to be held under lock and key until further advice was received.[59] These packets contained three documents: provisional war establishments for an overseas service contingent; tables of allotment of troops to districts; and draft military orders to authorise the raising of a ‘Second Australian Imperial Force’.[60] Only little of these plans is now knowable for certain, owing to their destruction after they were superseded. Nevertheless, CGS(A) White did confirm that the documents provided for ‘several contingencies’ requiring forces of varying size and composition.[61] Complementary instructions on the administration, recruitment, quartering, and equipping of a force were despatched to the district bases on 28 September by the Adjutant General’s and Quartermaster General’s branches in AHQ. Initially only ‘thoroughly trained … ex-members of the A.I.F’ were to be enrolled, with recruiting opened to unskilled volunteers only if necessary to reach establishments. Most commands were to be set aside for similarly experienced officers in the Citizens Military Forces (CMF), with a small portion of regimental appointments to go to permanent officers. These ‘preliminary instructions’ were provided to enable immediate action and ensure that the mistakes ‘which occurred in early stages of [the] organization of the A.I.F.’ were not repeated. Interestingly, ministerial approval had not yet been obtained for this framework prior to its dissemination, with district base commandants advised that ‘under no circumstances will any portion … [of the plan] be made public without authority from Army Headquarters’.[62] The pre-emptory communication of such plans to the district bases reflected the decentralised nature of Army administration and organisation of this period; each district base would have a key role in raising a portion of an overseas force as responsibility for initial recruitment, concentration and administration was devolved to them.

Although undertaken speedily, Army’s development of the ‘STAR’ plan was overtaken by events. In the first week of October the Chanak crisis dissipated as both sides accepted the need for negotiation rather than conflict.[63] The Army’s failure, in the early post-war period, to even consider expeditionary force planning was also obscured by the Hughes government’s reluctance to actually commit a force to overseas service. The crisis had nonetheless revealed that such a commitment was still possible, and that Army needed a set of coordinated contingency plans to enact if required. Personnel within AHQ, therefore, were ordered to continue development of the expeditionary force plans, with CGS(A) White reporting to CIGS Lord Cavan on 19 October 1922 that AHQ was ‘busy completing our plans in detail for much of similar events’ with ‘matters well in hand’, through this was complicated as copies of British war establishments had not yet been received. Regardless, White promised Cavan that the latter would ‘of course be consulted beforehand as to the size and composition of our quota’ if the raising of any such force appeared likely.[64]

Throughout October and into November 1922, AHQ continued to develop the procedures and policies that would guide the mobilisation of a future expeditionary force. Having initially been excluded from the planning process, on 14 November 1922 the district base commands were ordered to undertake their own subordinate planning, based on the principles and organisations developed by AHQ in the ‘STAR’ plan, for what was being called the ‘Plan of Concentration No. 401’. The role of the commandants in raising such a force was reinforced, as they were reminded that they were ‘responsible for the preparation of the plan and the organisation of the forces within their district upon the ordering of mobilisation’, with such plans to be submitted to AHQ for review by 1 February 1923.[65] Over subsequent months both AHQ and district-level plans were further developed. By August 1923, Chauvel—now both Inspector General and CGS(A)—was able to claim to Australia’s Military Representative in London, Brigadier General Thomas Blamey, that the plans to mobilise and deploy an expeditionary force of up to one division and a cavalry brigade were ‘complete and can be put into force at the shortest time, provided the Australian Army is not mobilized’.[66]

Yet Chauvel was overselling the completeness of the plans. Despite the efforts of AHQ staff, it was only in late September 1923 that a complete draft of its ‘Plan of Concentration 401’ was available for Chauvel to share with Adjutant General Major General Victor Sellheim for the latter’s comment and feedback.[67] This draft, Sellheim noted in his response, showed a ‘decided improvement on the existing plans’. Regardless, Sellheim advised that the title for the plan was misplaced, suggesting as alternatives ‘Plan of Organization 401’ or ‘War Plan 401’, and that the future force should be branded with the previously agreed title of ‘Second A.I.F.’ instead of the suggested designation of ‘Australian Expeditionary Force’. The reason for this preference was his concern that the abbreviation of the latter would undoubtably become confused with the abbreviation of the USA’s ‘American Expeditionary Force’ of the Great War. Beyond such matters, Sellheim requested a range of alterations to the plan’s principles regarding the appointment of recruiting staff, the pay of non-commissioned officers (NCOs), attestation procedures, administrative control of the deployed force, and the confirmation of appointments.[68] Chauvel readily acceded to many of Sellheim’s suggestions, though he did opt instead to change its designation to ‘Overseas Plan 401’.[69]

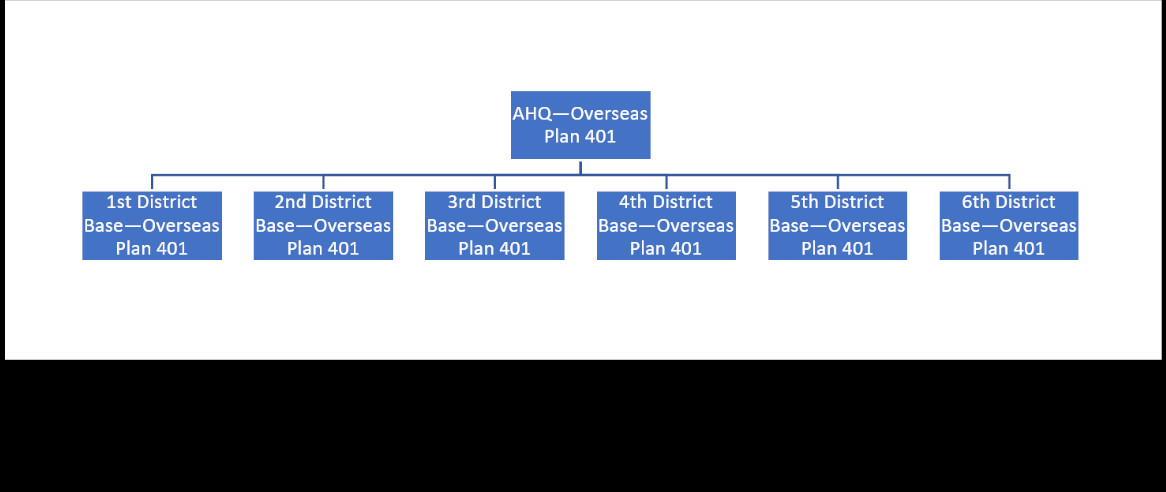

On 31 January 1924, with Sellheim’s amendments incorporated into AHQ’s guiding document, Chauvel circulated to the District Commandants a copy each of ‘Overseas Plan 401’, requesting that they revise their existing plans in accordingly.[70] As with the ‘STAR’ plan, no copy of AHQ’s ‘Overseas Plan 401’ of 1924 is identifiable in the archives, but the principles contained therein are clear through the available district-level subordinate plans (for the ‘Overseas Plan 401’ hierarchy, see Figure 1). AHQ’s ‘Overseas Plan 401’ comprised two parts: Part I contained the general principles upon which an expeditionary force was to be raised, and included instructions to guide the district bases in developing their subordinate plans; and Part II contained a summary of action to be taken by the branches and departments of Army Headquarters upon being ordered to raise the force itself. The principles that governed the force were simply stated. The plan was to be used to raise a force, following government direction for service overseas at a time when Australian territory was not threatened. While the difficulty of laying down the composition of the force to be raised ahead of time was acknowledged, four ‘alternative’ forces were provided as options, namely:

Force A: One Infantry Brigade Group with non-divisional and line of communications (L of C) units

Force B: One Division (less 1 Infantry Brigade Group)—that is, the units required to build up Force A to a complete division, together with certain additional non-divisional and L of C units

Force C: One Division with non-divisional and L of C units

Force D: One Cavalry Brigade Group with non-divisional and L of C units.

Upon deployment, each force would be accompanied by the necessary base and administrative depots to provide for national control and administration in distant theatres. With recruitment to be undertaken on a national basis, each military district would provide a set quota of recruits, specific units or even whole formations, with the most highly populated states, New South Wales and Victoria, having the largest quotas. Owing to the constraints of the Defence Act 1903, all recruits were to be volunteers, with preference in enlistment given to AIF veterans in the CMF, then to veterans no longer serving, with untrained recruits to be enlisted last and only if necessary. After attestation, personnel would be concentrated at locations specified within district-level plans, and formed into new units and formations. Reflecting the need to provide common nationwide procedures, ‘Overseas Plan 401’ contained specific policy guidance on topics such as eligibility and procedure of appointing officers, NCOs and other recruits to the force; organisation and procedures for recruiting; concentration of units and personnel; supply and transport; movement tables; quartering; issuing and accounting of equipment; initial training; medical and veterinary arrangements; and pay and finance.[71] Subordinate, district-level plans were required to account for and implement the guidance on all such matters.

Figure 1: Hierarchy of AHQ’s ‘Overseas Plan 401’ and the subordinate district-level implementation plans

The issue of the consolidated ‘Overseas Plan 401’ in January 1924 prompted necessary work within the district bases to update their plans in line with the new guidance from AHQ. Copies of the AHQ plan were also despatched by Chauvel to the CIGS in February 1924, along with a request for comment or revisions that could be incorporated into it, with a further copy sent to the GOC(NZ) in August 1924.[72] As an additional control measure, in mid-1924 AHQ’s Lieutenant Colonel Henry Wynter visited several districts ‘on duty in connection with mobilization and the preparation of Overseas Plan 401’, and to ‘examine the steps so far taken … in regard to these matters’.[73] Wynter, one of the brightest officers in the interwar Army, was intimately connected with the development in the period of ‘Overseas Plan 401’ and broader mobilisation planning, firstly as ‘S.O. [Staff Officer] Mobilization’ within AHQ’s General Staff Branch, and from February 1925 to November 1929 as AHQ’s ‘Director of Mobilization’.[74] Wynter’s oversight of district planning ensured that when the 2nd District Base submitted their ‘Overseas Plan 401’ to AHQ for review, he was able to request specific amendments to ensure it adhered to the principles and intent of the guiding document.[75]

Throughout the remainder of 1924 and into 1925–1926, further amendments to ‘Overseas Plan 401’ continued to be made both in AHQ and within the districts. On 13 August 1924, the final elements of the ‘STAR’ plan still in effect were superseded by new documents issued by AHQ.[76] In a rare, though limited, instance of interservice planning for the period, in 1925 AHQ worked with the Naval Staff to develop shipping tonnage tables—an analysis of the types and capacities of ships undertaking trading to Australia—to assess what kinds of vessels could be utilised to transport a force overseas at short notice.[77] Perhaps the most significant amendment made during this period was the change to ‘Small War’ establishments noted previously, along with significant amendments to district quotas, force compositions, and tables of organisation as promulgated in November 1925, though no details on the nature of these changes is available.[78]

By the close of 1926, both AHQ and the district bases had finalised development of their plans, and their attention was refocused on developing plans for the general mobilisation of the Army for the defence of Australia. Yet as the 1920s wore on, and the Army continued to struggle in the face of government parsimony, the Army’s ability to implement ‘Overseas Plan 401’ became ever more questionable. Not only were equipment stocks wholly insufficient, a factor fully acknowledged within AHQ and by the various ministers for defence in the period, but the core of ex-AIF veterans upon which ‘Overseas Plan 401’ relied continued to diminish in both quantity and suitability. Those veterans still serving in the CMF, and those universal service trainees who might volunteer for overseas service, offered a potential nucleus for an expeditionary force; yet with a requirement to attend only 12 days of training annually—eight days in camp and four in local drill halls—the level of individual and collective skills maintained was meagre.[79] Regardless, the voluntary overseas service principal meant Army had no mechanism to draw directly on such personnel unless they chose to volunteer. As the 1920s continued, and a new decade dawned, the Army’s force in being (FIB) offered an ever-worsening foundation for the mobilisation of an expeditionary force.

[49] Quoted in W David McIntyre, New Zealand Prepares for War: Defence Policy 1919–39 (Christchurch: University of Canterbury Press, 1988), p. 71.

[50] Ronald Munro Ferguson to Lord Milner, 24 September 1920, TNA: CO 532/158.

[51] Military Board, ‘Draft Military Order—Army Headquarters Mobilisation Committee’, 29 April 1921, NAA: MP367/1, 535/1/44, 360085.

[52] Military Board, ‘Appointment of Committee to Formulate a Scheme of Administration for Use in event of Future Mobilisation’, 9 March 1921, NAA: A2653, 1921 Volume 1, 227642.

[53] War Office, Field Service Regulations—Volume I: Organization and Administration—1923 (Provisional) (London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1923), pp. 9–10. See also War Office, Field Service Regulations—Part II: Organization and Administration, 1909 (London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1913).

[54] War Office, ‘Handbook dealing with the Military Aspect of Imperial Defence’, May 1921, NAA: A5954, 1776/15, 655708.

[55] ‘Chanak’ was the anglicised name for what is modern Ҫanakkale.

[56] Winston Churchill to Governor-General Henry Forster, 16 September 1922, NAA: CP78/32, 1, 353292.

[57] William Hughes, ‘Statement made by Prime Minister re Turkish Situation’, 19 September 1922, NAA: CP78/32, 1, 353292.

[58] Jeffrey Grey, The Australian Army: A History (South Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 2006), pp. 78–79; Palazzo, The Australian Army, 105.

[59] Brudenell White to Headquarters 2nd District Base, 30 September 1922, AWM: AWM193, 345 part 3, 1967995.

[60] Henry Wynter to HQ 2nd District Base, ‘Plans for the Raising, Preparation and Despatch of an Expeditionary Force for Service Overseas’, 13 August 1924, AWM: AWM193, 345 part 2, 1967994.

[61] CGS(A) Brundell White to CIGS Lord Cavan, 19 October 1922, LAC: DND Fonds, R11-2-890-6-E, file 3602, MR C-8294.

[62] Cecil Foott to HQ 2nd District Base, ‘The Second Australian Imperial Force’, 28 September 1922, AWM: AWM193, 345 part 3, 1967995.

[63] See David French, Deterrence, Coercion, and Appeasement: British Grand Strategy, 1919–1940 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022), pp. 130–132, 145–146.

[64] CGS(A) Brundell White to CIGS Lord Cavan, 19 October 1922, LAC: DND Fonds, R11-2-890-6-E, file 3602, MR C-8294.

[65] Brudenell White to Charles Brand, ‘Plan of Concentration, No. 401’, 14 November 1922, AWM: AWM193, 345 part 3, 1967995.

[66] Harry Chauvel to Thomas Blamey, 31 August 1923, AWM: AWM113, MH 1/21, 664704.

[67] Chauvel to Sellheim, ‘Plan of Concentration 401’, 28 September 1923, NAA: B197, 1925/1/133, 419070.

[68] Sellheim to Chauvel, ‘Plan of Concentration 401’, 11 October 1923, NAA: B197, 1925/1/133, 419070.

[69] Chauvel to Sellheim, ‘Plan of Concentration 401’, 9 January 1924, NAA: B197, 1925/1/133, 419070.

[70] Chauvel to HQ 1st District Base, ‘Overseas Plan 401’, 31 January 1924, NAA: B197, 1925/1/133, 419070.

[71] ‘3rd District Base—Overseas Plan 401’, [c. November] 1926, AWM: AWM51, 179A, 493774.

[72] Cavan to Chauvel, 9 April 1924, NAA: B197, 1925/1/133, 419070.

[73] Henry Winter to HQ 2nd District Base, 11 July 1924, NAA: B197, 1925/1/133, 419070; Chauvel to Major-General Charles Melvill, 30 August 1924, NAA: B197, 1925/1/133, 419070.

[74] ‘Proceedings of a Committee assembled at Army Headquarters on the 11th and 12th September, 1924’, 12 September 1924, NAA: A2653, 1924 Volume 1, 227651; The Army List of the Australian Military Forces: Part 1. ACTIVE LIST and A.A.M.C. Reserve (Melbourne: H. J. Green, 30 September 1937), p. 307.

[75] Wynter to HQ 2nd District Base, ‘Overseas Plan 401’, 3 September 1924, AWM: AWM193, 345 part 2, 1967994.

[76] Wynter to HQ 2nd District Base, ‘Plans for the Raising, Preparation and Despatch of an Expeditionary Force for Service Overseas’, 13 August 1924, AWM: AWM193, 345 part 2, 1967994.

[77] Bruche to Francis Heritage, ‘Oversea Plan 401’, 40 April 1933, NAA: B197, 1925/3/29, 419060.

[78] Chauvel to the Military Board, ‘Mobilization Preparations: War Establishments to be Utilized’, 5 September 1924, NAA: A2653, 1294 Volume 2, 227652; Wynter to HQ 2nd District Base, ‘Overseas Plan 401’, 12 November 1925, AWM: AWM193, 345 part 1, 1967992.

[79] Army Headquarters, ‘Note on Australian Army Policy and Activities for Use of Minister of Defence during his forthcoming visit to Ottawa’, 19 June 1928, NAA: A5954, 2390/1, 240390.

By 1931 it had become widely recognised that ‘Overseas Plan 401’, as formulated in 1923–1926, was no longer a viable plan upon which to raise a force for overseas service. As Bruche noted to CIGS Field Marshal Sir George Milne in October 1931, revision of the plan had:

become necessary owing to changes in our organization arising out of the discontinuance of compulsory military training and to the fact that only a negligible proportion of our ex-service men, upon whom we were relying mainly to provide our first contingent, are now of suitable age for inclusion in an Expeditionary Force.[80]

Revisions to the plan, however, had been initiated under Bruche’s predecessor as CGS(A), Major General Walter Coxen, who on 2 May 1931 had forwarded to his Military Board colleagues a revised draft of Part I for their comment. The new version contained substantial revisions, including provision to raise a ‘special force’ in addition to Forces A to D; removal of preference in enlisting AIF veterans; the allotment of CMF battalion areas as recruiting areas; decentralised enlistment processes within the districts (enlistments being no longer required to be conducted at a ‘Central Enlisting Office’); and changes in the procedures for detailing recruits to training camps and conducting medical re-examinations. A new appendix altering the allotment of quotas to the districts was also to be provided.[81] Responding to Coxen in July and August respectively, Quartermaster General Major General Charles Brand and Adjutant General Major General Thomas Dodds provided their own suggested updates to the plan in their areas of responsibility.[82] An indication of further changes to the previous plan, principally within the order of battle (ORBAT) for Force B/C were also flagged in October 1931.

The changes were extensive, and indicated Army’s focus on capability development. In deploying a division-sized expeditionary force, ‘Overseas Plan 401’ provided for the mobilisation of two air defence brigades and a tank battalion. The inclusion of both, for which equipment or manufacturing capacity did not exist in Australia, was an attempt to justify the acquisition of both equipment and trained personnel so such units could eventually be raised in the militia. Bruche, however, questioned the wisdom of including such forces within the ORBAT as they would ‘consist of personnel only and will be required to be provided with their armament and equipment and be trained after arrival overseas’.[83] The proportion of artillery and anti-air establishments in the revised ORBAT was significant, suggesting that it was now intended that the overseas force would be sufficiently equipped to engage a peer or near-peer enemy. Force B/C would include not only four artillery brigades within the division itself, but two anti-aircraft brigades and a medium artillery brigade as non-divisional (potentially corps-level) units.[84]

The revised ‘Overseas Plan 401’ was promulgated on 1 March 1932. As in previous processes, copies were issued to each district base and commandants were requested to revise their plans in line with the updated principles.[85] The CIGS had again been asked to provide advice on the revised plan, and his views had been received by July 1932. By and large the CIGS’s suggestions were incorporated into the plan, though Bruche did ensure the inclusion of some further sub-units in the force structures (possibly suggested as non-essential by the CIGS), such as provost or signals sections of Forces A and D (the brigade groups). While Forces A and D had been designed to slot within a multinational division of a larger British expeditionary force, Australia’s autonomy as a member of the Commonwealth required that Australian units maintain a separate ‘national identity’ as far as possible, even when operating closely with and within British formations.[86]

In his dealings with the CIGS, Bruche was at pains to remind him that each of the alternative forces contained units for which equipment was ‘not at present available in Australia’ and unlikely to be attained for a ‘considerable period’. These included capabilities such as light and medium tanks, anti-aircraft artillery, and searchlight equipment which would have to be provided from British sources upon mobilisation or arrival overseas. In correspondence with the CIGS, Bruche remarked that if an Australian expeditionary force could ‘arrive in a Theatre of war West of Suez within 3 months of the decision being taken to raise it’, he would be interested ‘to learn whether this equipment could be made available by the War Office on its arrival’.[87] The War Office’s response to this question is unclear, though the fact Bruche maintained within the alternative ORBATs units for which there was no equipment available in Australia, and which would have to receive such equipment from Britain, suggests that he received a positive response. On 1 September 1932 a further revised version of AHQ’s ‘Overseas Plan 401’, which included the CIGS’s accepted amendments to the ORBAT, was compiled and subsequently issued to the districts, the latter being advised that the new version made no amendments to the method of raising the force but that it contained substantial revisions to the ORBAT and its accompanying establishment tables.[88]

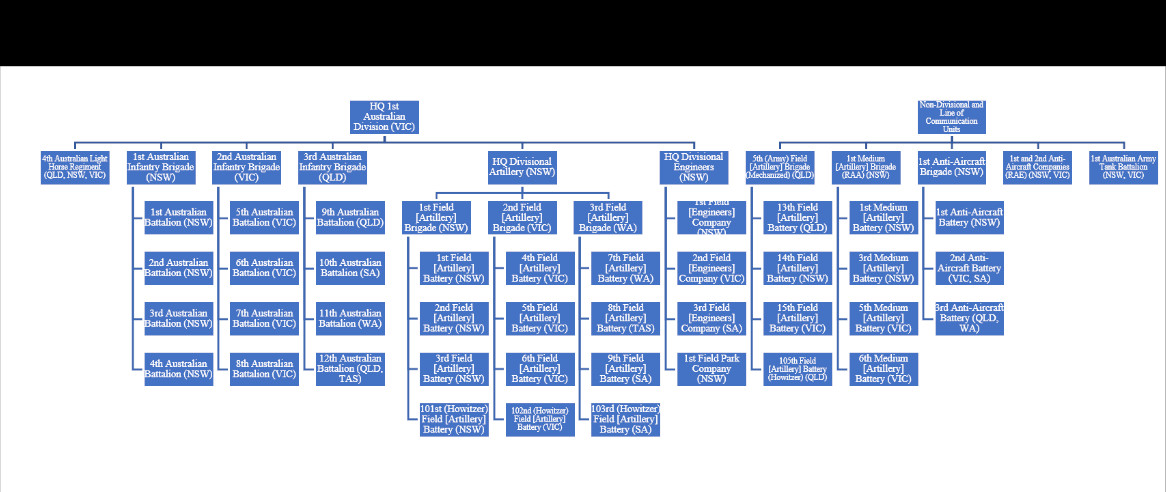

It is worth pausing here to consider in more detail the composition of the four forces contained within ‘Overseas Plan 401’, and the geographical basis upon which they were to draw recruits.[89] Despite four alternative forces entailed within the plan, only three differing force structures actually appear. This is because Force B was designed as a follow-up contingent to reinforce Force A (an infantry brigade group) up to a division (Force C). Force A comprised an infantry brigade of four battalions, a field artillery brigade of four batteries, a field engineer company, and a range of enabling sub-units for signalling, supply and transport, provost, postal, and medical. Force D, meanwhile, consisted of a cavalry brigade of three Light Horse Regiments, an armoured car regiment, one field artillery battery, a field engineering troop, and a similar proportion of enablers as Force A. Force C, encompassing an infantry division and significant non-divisional and L of C units, was the largest force contemplated (see Figure 2). Its structure and recruitment areas harked back to that of the 1st Australian Division of the First World War with, for example, the 1st Australian Infantry Brigade of Force C and the 1st Australian Division to be recruited wholly from New South Wales, while the battalions of the 3rd Infantry Brigade were drawn from Queensland, South Australia, Western Australia and Tasmania. Even the designation of the division’s reconnaissance regiment—the 4th Australian Light Horse Regiment—was identical to that which accompanied the 1st Australian Division abroad in 1914, though in Force C it would be drawn from Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria rather than just the latter.[90] In line with the Army’s organisational philosophy of the time, field formations were recruited (and, in theory, reinforced) on a territorial basis rather than through a centralised recruiting and duty-allotment system such as that now used by the ADF.

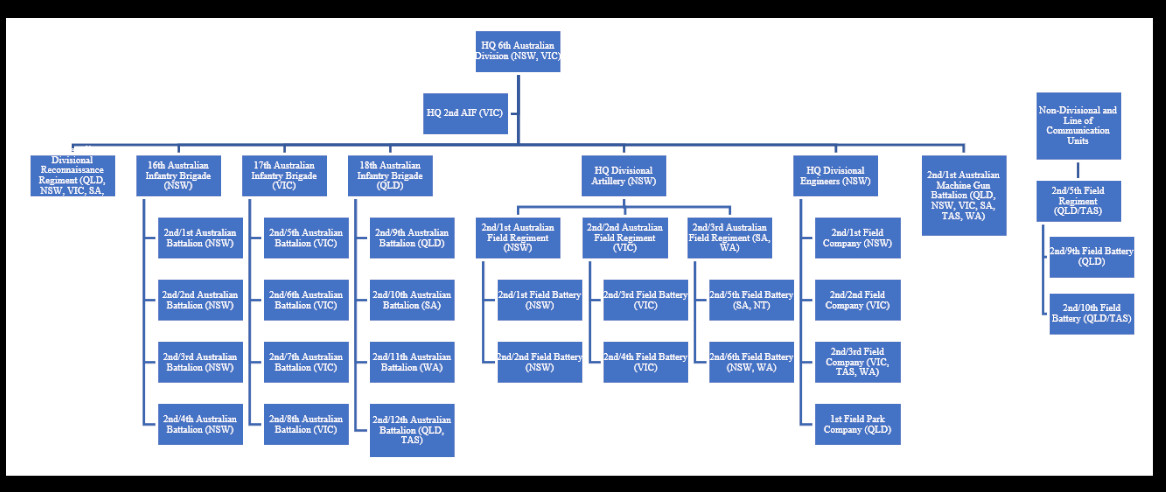

Following revisions to the ORBAT in mid-1938, Force C was to be accompanied abroad by a mechanised artillery brigade, a medium artillery brigade, an anti-aircraft artillery brigade, two anti-aircraft engineering companies, and an army tank battalion. In reality, the lack of equipment made each of these formations little more than an aspirational target. A 1938 army tank battalion, for example, required 23 light tanks, 19 medium tanks, and eight close support (or ‘infantry’) tanks (50 total); in 1938 in the whole of Australia there were only four Vickers Medium Mark IIs which had been delivered in 1929, and 11 modern Mark VIA Light Tanks which arrived in late 1937 (15 total). A further 24 light tanks were on order from Britain, though no timeline for delivery had been provided.[91] Ultimately the division that would be mobilised in 1939 through ‘Overseas Plan 401’, the 6th Australian Division, would take a similar form to that contained within the plan (see Figure 2). There would, however be significant differences. The Light Horse Regiment was replaced with a mechanised divisional reconnaissance regiment, the artillery brigades were restructured into field regiments of two batteries (in line with British establishments), and a machine gun battalion was added to the ORBAT. There were also significant reductions in the non-divisional troops; the medium brigade, the anti-aircraft brigade, the anti-aircraft engineer companies, and the tank battalion were all removed from the force structure.[92]

Figure 2: ORBAT of Force C, including amendments to mid-1938 but excluding enablers such as signals, logistics or medical units[93]

Figure 3: ORBAT of 6th Australian Division, excluding enablers such as signals, logistics and medical units, as of December 1939, prior to its departure overseas[94]

Yet the mobilisation of 6th Australian Division would not occur for several years. Further updates and revisions to ‘Overseas Plan 401’ continued to be made in the years following its promulgation in September 1932, as geopolitical instability heightened. In June 1933, work was initiated in the Quartermaster General’s Branch at AHQ, in tandem again with the Naval Staff, to update the shipping tonnage tables, though a lack of staff within the branch slowed progress.[95] With the rapid mobilisation of an overseas force seemingly more likely, in July 1933 the Director of Military Operations and Intelligence in AHQ, Colonel Vernon Sturdee, requested that the veil of secrecy surrounding district-level ‘Overseas Plan 401’ be extended. While previously the particulars of the district plans were to ‘be known only to the officers required to complete the peace time preparations’, this status was to be altered. Now the system of recruiting and drafting of recruits into concentration areas was to be briefed to a wider body of Staff Corps officers and members of the Australian Instructional Corps within both district base headquarters and CMF formations.[96]

As 1934 drew to a close, further work on ‘Overseas Plan 401’ slowed. This was despite the advice of Hankey, who visited Australia in September–November 1934 to advise the Lyons government on defence matters. Ever the staunch supporter of intimate defence ties between Commonwealth nations, Hankey had expressed support for Australian expeditionary force plans to be discussed and coordinated with the War Office. This had been the standard procedure for many years, and in February 1934 Bruche forwarded updated copies of ‘Overseas Plan 401’ to both CIGS Lord Milne and GOC(NZ) Major General Sir William Sinclair-Burgess. The latter noted that the plan would be ‘of the greatest assistance to us’ as New Zealand worked ‘on similar schemes’, with it potentially being ‘of great service in ensuring co-operation’.[97] With little more development on ‘Overseas Plan 401’ being undertaken, it was therefore a surprise to the now CGS(A) Major General John Lavarack when, in November 1935, he was advised by Sinclair-Burgess that the New Zealand Military Forces had developed plans for the despatch of an expeditionary force of one cavalry brigade and attached groups, named ‘Plan E’ or ‘Force E’. This force, Sinclair-Burgess felt, should be:

Looked upon as the other cavalry brigade etc. with which your Force D should combine to form a cavalry division. In the event these expeditionary forces being required, a combination between Australia and New Zealand, as in the last war, seems more natural than that either of the forces should be combined with an unknown English formation.

Although he sought Lavarack’s views, Sinclair-Burgess was evidently enthusiastically committed to the proposal. In his letter to Lavarack he delved into the possible composition of the divisional headquarters, how appointments could be shared—including noting that he would be ‘quite agreeable to the initial divisional commander being an Australian’—and how the balance of troops required to form the division could be apportioned between each Army.[98] Given the signing of ‘Plan Anzac’ by the Australian and New Zealand Chiefs of Army on 17 April 2023, of which outcome one was the ability to integrate a New Zealand motorised infantry battle group into an Australian brigade, this suggestion by Sinclair-Burgess is of note.[99] Lavarack duly responded in January 1936, confirming that he had ‘read your proposal with interest and am in agreement in general principle’ as ‘Australian and New Zealand Forces should work in close co-operation as in the last War’. He added, however, that:

[the] question is not of immediate urgency, and that its fulfilment would depend upon the attitude of our respective Governments at the time when the need for the despatch of expeditionary forces became more apparent.

Lavarack poured further cold water on the suggestion, highlighting the differences in organisation and equipment between the two potential forces, and that further contingencies would need to be developed that would allow either country to deploy an expeditionary force singly or in cooperation.[100]

Lavarack’s rejection of Sinclair-Burgess’s proposal was shortsighted as it could have been further developed without significant staff effort. However, Lavarack’s perspective was undoubtedly influenced by his all-too-extensive understanding of the difficulties entailed in mobilising an Australian expeditionary force. As Lavarack noted in May 1936, the Army’s lack of anti-tank guns or rifles, Bren light machine guns, machine-gun carrier tanks, armoured cars, anti-aircraft equipment and motor transport necessitated that any force sent abroad would be only partially trained and armed with personal equipment only. As a result, it would need a ‘reasonable period’ of training, after being equipped from British stocks in theatre, before it would be prepared for operations.[101] Lavarack’s realistic assessment regarding the mobilisation of an overseas contingent was given full force in a private letter to Lieutenant General John Dill, a friend in the British Army, stating:

If you imagine that within a year of the outbreak of war you will have [an Australian expeditionary force] approaching the standard of Passchendaele or the 8th of August, forget it. The standard of leadership, of man-power actually serving, of training, and of equipment is now far lower, relatively, than it was avant la guerre in 1914. You saw the A.I.F. as it was from late 1917 onwards, but it had not really found itself … until about the middle of 1917, i.e. until] after 2.5 to 3 years of solid training and war experience. It will take as long next time.[102]

The accuracy of Lavarack’s assessment would largely be borne out during the early years of the Second World War.

As Army entered 1938, continued development of ‘Overseas Plan 401’ at both the AHQ and district levels remained a low priority. Aside from occasional amendments to the plan, staff effort was instead focused on mobilisation of the Army’s First Line Component—a portion of the CMF theoretically kept at a higher readiness to defend against raids on continental Australia. These priorities were altered in March 1938 based on Lavarack’s assessment that a European war was becoming ever more likely.[103] Within two months, a series of updates to the plan’s ORBATs were developed. Seeing an opportunity, both the Quartermaster General’s Branch and the Adjutant General’s Branch also suggested their own amendments, the results being consolidated and forwarded to the districts so they could again update their plans.[104] By July 1938, the international situation had deteriorated to such a point that AHQ was undertaking ‘intensive war planning’.[105] Such planning was prioritised during, and in the aftermath of, the September 1938 Sudeten crisis. Army was ordered to complete its war plans ‘with the greatest possible expedition’, a direction that was passed on by AHQ to all formations, bases and schools when it ordered that all staff were to regard ‘war preparation work [as] their primary duty at the present time’.[106] The tempo of planning slowed in response to the easing of international tensions evidenced by the signing of the Munich Agreement on 30 September. Nevertheless, Army continued to update its existing mobilisation plans—including ‘Overseas Plan 401’—through a ‘specially co-ordinated and intensive programme’ to ensure suitable progress before a further international crisis.[107] When this crisis ultimately manifested in September 1939, Army’s mobilisation plans were incomplete, but relative to 1914 they represented a quantum leap in preparation. Although still under revision when Australia declared war upon Nazi Germany on 3 September 1939, ‘Overseas Plan 401’ nevertheless offered a clear path for the mobilisation of an expeditionary force. Yet Army, on the whole, remained poorly placed to actually raise the force. The strategic situation was uncertain, with Japan’s intentions in the Asia-Pacific unclear and the government of Prime Minister Menzies therefore reluctant to denude Australia of its scarce trained manpower and equipment. Further, the post-Depression attempts to improve, expand and re-equip the Army had yet to yield significant results. Despite the haste with which an overseas contingent could have been raised through ‘Overseas Plan 401’, it was not until 15 September that Menzies announced the formation of an expeditionary force, 3 October that a revised ORBAT for the force was issued by the Military Board, 13 October that the force commander (Major General Sir Thomas Blamey) was gazetted, and 20 October that the first recruits were attested.[108] Despite multiple iterations over the years, ‘Overseas Plan 401’ was ultimately enacted to mobilise the 6th Australian Division, and its existence undoubtedly contributed to the relatively smooth raising of the formation and its associated non-divisional units (see Figure 3) throughout late 1939 and into 1940.

The actual raising and despatch of the 6th Australian Division has already been extensively analysed in other histories, and does not need repeating here.[109] Some particularly relevant observations, however, are warranted. Though the formation’s mobilisation was, on the whole, smoothly executed, it was not without issue, a factor that was identified contemporaneously. Some of the principal problems were:

While relevant, the source of Army’s and government’s biggest failure in preparing for an expeditionary force was not deficiency in ‘Overseas Plan 401’. Instead it was the situation of general decay that existed within Army, and the inadequate FIB upon which an overseas contingent had to be raised. John Blaxland correctly identifies that the Army’s interwar decline meant it faced ‘a formidable task in preparing for war, one that would take months if not years and would tax their abilities to the utmost’.[112] Given the litany of deficiencies of the interwar Australian Army—including, but not limited to, inadequate training and experience opportunities at all levels, shortages of modern equipment, and the lack of joint planning with the naval and air staffs—it is altogether unsurprising that it took the 6th Division some 14.5 months to reach sufficient operational capability to enter its first action at Bardia on 3–5 January 1941. The fact that this delay did not imperil the defence of Australia or its territory was due to two factors: the strategic depth provided by the expanse and strength of the British Empire, and the fact that, until 1941, Army did not have to face a regional adversary. This situation is unlikely to exist in future conflicts.

[80] Bruche to Milne, ‘Periodical Letter No. 4/1931’, 22 October 1931, NAA: B197, 1987/2/104, 418389.

[81] Bruche to the Adjutant-General, Quartermaster-General, and Finance Member, ‘Overseas Plan 401’, 2 May 1931, NAA: B197, 1925/3/28, 419057.

[82] Brand to Coxen, ‘Overseas Plan 401’, 16 July 1931, NAA: B197, 1925/3/28, 419057; Dodds to Coxen, ‘Overseas Plan 401’, 14 August 1931, NAA: B197, 1925/3/28, 419057.

[83] Bruche to Milne, ‘Periodical Letter No. 4/1931’, 22 October 1931, NAA: B197, 1987/2/104, 418389.

[84] See Army Headquarters, ‘OVERSEAS PLAN 401: Revised to 1st September, 1932’, 1 September 1932, AWM: AWM113, MH 1/66 D, 664891.

[85] Colonel John Lavarack to District Base Headquarters, ‘Overseas Plan 401. Revised 1st March, 1932’, 17 March 1932, NAA: B197, 1925/3/29, 419060.

[86] Bruche to Milne, ‘Periodical Letter No. 3/1932’, 20 July 1932, LAC: DND Fonds, R11-2-890-6-E, file 3602, MR C-8294.

[87] Bruche to Milne, ‘Periodical Letter No. 4/1932’, 25 October 1932, LAC: DND Fonds, R11-2-890-6-E, file 3602, MR C-8294.

[88] Lavarack to District Base Headquarters, ‘Overseas Plan 401 (Revised to 1st September, 1932)’, 26 September 1932, AWM: AWM54,

[89] The analysis regarding force structures contained within this paragraph is drawn from Army Headquarters, ‘OVERSEAS PLAN 401: Revised to 1st September, 1932’, 1 September 1932, AWM: AWM113, MH 1/66 D, 664891.

[90] For an organisational diagram outlining the structure and recruitment areas for the 1st Australian Division of 1914, see Robert C Stevenson, To Win the Battle: The 1st Australian Division in the Great War, 1914–18 (Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 2013), p. 42.

[91] War Office, Mobile Division Training Pamphlet No. 2—Notes on the Employment of the Tank Brigade, 1938 (London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1938), p. 35; RNL Hopkins, Australian Armour: A History of the Royal Australian Armoured Corps 1927–1972 (Canberra: Australian War Memorial, 1978), pp. 15–16, 22.

[92] For the ORBAT of the 6th Australian Division in December 1939, see ‘Order of Battle: 2nd Australian Imperial Force—6th Division and Ancillary Troops’, n.d. [c. January 1940], AWM: AWM52, 1/5/12; and Graham R McKenzie-Smith, The Unit Guide: The Australian Army 1939–1945 (Newport: Big Sky Publishing, 2018).

[93] Table drawn from appendices IIA and IIB in Army Headquarters, ‘OVERSEAS PLAN 401: Revised to 1st September, 1932’, 1 September 1932, AWM: AWM113, MH 1/66 D, 664891.