The Social Identity Foundations of Military Leadership

Group affiliation and identity are key themes in Anthony King’s rich and extensive analysis of military cohesion and performance The Combat Soldier.[1] King argues that understanding operational performance depends crucially on understanding the nature of ‘collectives’. He shows how longstanding practices in military doctrine and training aim to enhance group cohesion by shaping affiliation and identity, so that the execution of orders by soldiers will be increasingly willing, sophisticated and coordinated. King uses a sociological perspective to show how group processes are critical to military effectiveness. He begins by arguing that the platoon is analogous to indigenous communities as studied by Durkheim, in terms of its function in individual survival, morality and epistemology. He goes on to demonstrate how the behaviour of individual soldiers is shaped by their group memberships, and that we can make sense of the willingness of military personnel to expose themselves to great personal risk—potentially including the ultimate individual sacrifice—only by understanding that groups and societies (collectives) are more than simply the sum of the individuals within them.

Consistent with King’s sociological approach, the aim of this article is to put the case for a collectivistic psychological perspective in understanding the powerful ‘people factors’ that are crucial to military effectiveness. We explain how a genre of social psychological scholarship known as the social identity approach can bring new clarity to notoriously opaque military leadership processes.[2] We begin with an introduction to the social identity approach,[3] including its role as a refreshing antidote to the dominant individualistic versions of psychology. We then demonstrate how social identities, which at heart are a psychological sense of ‘us’, underpin established Australian military leadership practice. Drawing on the academic literature (including empirical studies conducted in American and European military institutions) and observations of the Australian military, we show how—whether they know it or not—Australian Defence Force (ADF) members tend to be habitual managers of social identities, empowered by institutionally entrenched support structures that build and sustain relevant military organisational identities. Finally, informed by recent reflections from mid-career members attending the Australian Command and Staff Course (ACSC), we show how a deeper appreciation of the social identity approach to leadership can enhance standard practice, particularly by curbing some common misperceptions of military leadership. Despite our Australian military research focus, the psychological principles covered herein are applicable to militaries the world over, and servicemen/women of any nation can use such knowledge to enhance their personal leadership capabilities and those of their teams.

The Social Identity Approach

The social identity approach derives its label from the central insight that self-definition will at times be determined by our social identities.[4] Our sense of ourselves as being a member of various in-groups (or, colloquially, ‘tribes’) not only allows us to understand our place in the world but is also a potential source of dignity and pride. Social identities include nations (e.g., ‘we Australians’), political movements (e.g., ‘we Republicans’) and fandoms (e.g., ‘we Manchester United supporters’). Our social identities also shape our perception of fellow in-group members so that we come to see them as cognitively equivalent to each other, including to ourselves. That perceived equivalence is the psychological backbone of critically important phenomena such as affinity, empathy, altruism and cooperation.[5] And social identities are also a psychological prerequisite for generally objectionable, but nonetheless powerfully influential, phenomena such as intergroup conflict and discrimination.[6]

Paradoxically, the social identity perspective continues to hold a minority position in psychological thinking. As a burgeoning science, psychology suffers greatly from theoretical disunity, with many of the most basic assumptions of the field still being contested.[7] Part of this disunity concerns the treatment of the collectivistic lens across different continents. Psychological research that emerged from Europe in the mid-20th century was comfortable with embedding group and societal processes into psychological theories, which is the intellectual ancestry of the social identity approach.[8] Building on the iconic work of Muzafer Sherif, Kurt Lewin and others, social identity theorists demonstrated that a psychological process of self-definition in terms of ‘us’ is core to the processes that allow groups of individuals to develop into societies, and societies to develop individuals. From this perspective, individual psychology remains incomplete without the input from some society or group context, where social identities allow that input to occur. In contrast, North American psychology is synchronised with the individualistic zeitgeist of the USA. It has thus tended to reject or ignore the society-to-individual link, focusing instead on the search for psychological insight into inherent individual desires, tendencies and capacities, as well as subjects’ developmental and interpersonal histories.[9] The consequence has been two quite different psychologies. On one hand, European psychology has been comfortable in recognising humans as cultural animals who are defined by the groups and societies that they inhabit, whereas North American psychology is inclined to reify the individual independent of those elements, and in many respects pathologises the influences of one’s social context. The North American psychology became dominant due to a complexity of factors, including the political.[10] Indeed, if readers were to open any introductory textbook on psychology, leadership or management and then turn to the content covering ‘groups’, they would read almost exclusively of social ills, such as groupthink, social loafing and the bystander effect. In the same vein, those textbooks usually include Stanley Milgram’s Yale obedience experiments, and Philip Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison study, which both tend to be interpreted as demonstrations of how social and group forces are a cause of great harm.[11]

An important consequence of this schism between collectivistic psychology and individualistic psychology, and the dominance of the North American voices propagating the latter, is the continued dominance of the individualistic mythology of leadership.[12] That mythology focuses exclusively on the leadership potential of an individual, paying tokenistic attention to the context and people around that individual. The individualistic lens presumes that leadership is an enduring characteristic of certain people, an analytic tradition also strongly influenced by pre-scientific ‘great man’ leadership narratives.[13] The great man account of leadership proposes that ‘leadership’ is something that people possess to varying degrees, and that those who have this quality are predestined for great accomplishment. While such narratives continue to be influential, serious scholarship on leadership has long rejected the individualistic lens in favor of a relational understanding of leadership, with appropriate emphasis on the follower’s role in generating leadership. Such scholarship gives appropriate weight to people’s responses to leadership efforts, at the same time as examining the actions of people who try to ‘lead’. This approach recognises that the beliefs of followers (e.g., which of one’s peers are seen as trustworthy, fair and courageous) are central to leadership, rather than being a peripheral or second-order factor. Yet even then, most relational perspectives on leadership remain individualistic, in the sense that analysis is limited to interpersonal factors. Intergroup and intragroup interactions (by which encounters between people are given meaning by group and societal context) are generally neglected. The insights of European psychology—and in particular the social identity approach—act as a necessary counter to that notion of leadership individualism, by embedding the group and society into the essence of human psychology. For the social identity approach, self-definition in terms of ‘we’ or ‘us’ is as essential, valid, meaningful and motivating as our sense of ourselves as individuals (i.e., in terms of ‘I’).

The Social Identity Approach to Leadership

The social identity approach began as an attempt to better understand intergroup conflict and prejudice.[14] Over subsequent decades, however, social identity insights were used to shed light on phenomena such as group polarisation, crowd behaviour, health and wellbeing, personality, power and influence.[15] One result of this broad perspective on human behaviour is that the social identity approach has never lionised ‘leadership’, in the sense of the sliver of organisational life that is most conspicuous to organisational elites. Instead, the social identity approach truly accepts the message that leadership is best understood as being fundamentally about influence, wherever it occurs. Research into leadership should therefore start with the question: when and why will influence occur? The investigation that follows focuses on the relationship between an influencer and an influencee. Moreover, those who ultimately decide whether influence occurs are the influencees; it is in their minds, after all, that an attitude, belief or behaviour is accepted or rejected. Thus the most fruitful pathway to understanding leadership is not so much to scrutinise those seen to be ‘leaders’ as to understand the psychology of those who follow them.

Militaries are among the best examples of the potency and utility of social identification. The subsumption of ‘self’ into military organisations is so powerful and profound that the requirement to lay down one’s life in service of the mission is experienced as an almost unremarkable reality of military service. For many service personnel, the experience of being Australian Navy, Army or Air Force, or some subgroup within (e.g., submariner, gunner, pilot) embeds itself so deeply in one’s sense of self that it is hard to imagine living in its absence. It is by looking in from the outside that the contours and effect of social identities across military organisations are most readily apparent. Nobel prize winner George Akerlof and Rachel Kranton use the extremity of the military example to make the reality of organisational identification clear to everyday readers:

[T]he military makes investments to turn outsiders into insiders. Initiation rites, short haircuts, boot camp, uniforms, and oaths of office are among the obvious means of creating a common identity. The routine of the military academies also shows some of the tools used to inculcate military identity. Harsh training exercises and hazing, like the R-Day rituals at West Point, are just one way the Army puts its imprint on cadets.[16]

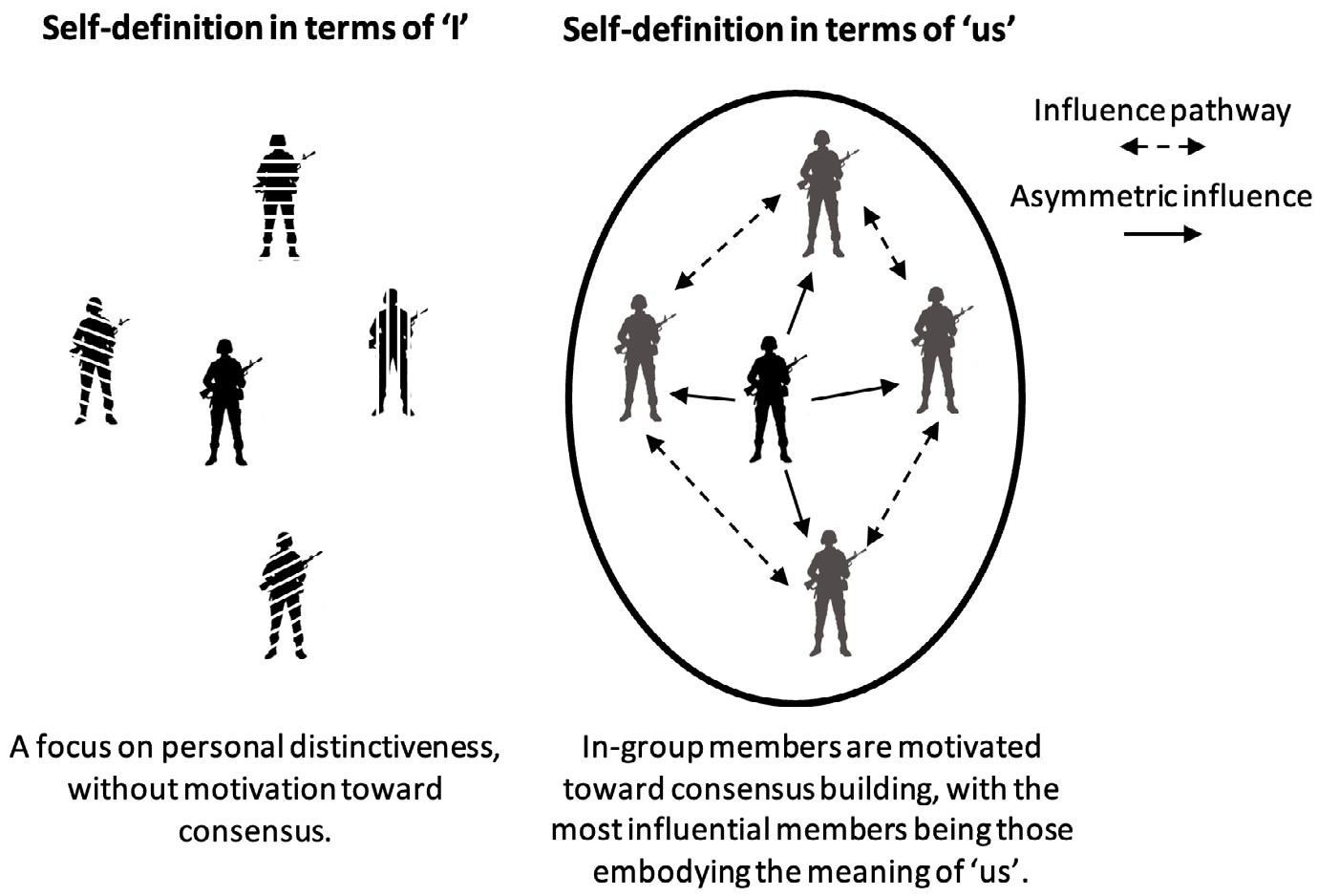

Social identities are integral to influence because we are predisposed to listen to those who we consider to be part of our in-groups.[17] We come to perceive our fellow in-group members as cognitively interchangeable with ourselves—for example, listening to their opinions can be akin to listening to our own trusted beliefs. But fellow in-group members are not all equally good presentations of our social identity, and if there is any ambiguity about how ‘we’ should act, talk or think, our first point of reference will be the person who best exemplifies what it means to be ‘us’. As depicted in Figure 1, in these moments we are most influenced by those who typify what we are good at and what we stand for—said otherwise, those who are the best versions of us, judged in terms of the behaviours and beliefs valued from the perspective of in-group members. It is not unreasonable to call these most influential in-group members the ‘leaders’.[18]

Figure 1: Social Identities Create Motivation for Consensus Seeking Among In-group Members

The social identity approach is an a-normative theory of leadership. Normative theories are those that presuppose particular social goals or policy positions. In contrast, the social identity approach is an unvarnished analysis of the cognitive mechanisms that fuel a particular type of influence, regardless of whether that influence renders help or harm to society. It applies as much to suicide bombers[19] as it does to charity workers,[20] and to the leaders of criminal gangs as much as to the leaders of emergency services brigades.[21]The presence of ethical norms within an in-group that are inconsistent with those of a broader society in no way diminishes the reality that those in-group ethics will be fundamental to who is seen to be the best of ‘us’.

Empirical Support

Supporting evidence for the social identity approach to leadership includes laboratory experimentation, field experimentation, observational studies, and longitudinal research.[22] Many of the early studies that provide empirical support for the social identity approach to leadership were undertaken in military institutions. For example, one of the first studies to explicitly investigate the relationship between social identification and leadership in the military was the work of Boas Shamir and his colleagues. In a sample across 50 field companies from the Israel Defense Forces, totalling upward of 900 staff and soldiers (including infantry, armoured and engineering), they found that commanders who emphasised unit collective identity had units with more cultural symbols (e.g., songs, jargon), and that units with stronger identity possessed greater discipline and vigour.[23] Other evidence of a similar nature, linking social identification with military performance, has been obtained from studies of Norwegian military academy cadets,[24] West Point cadets in the USA,[25] and US Army reservists.[26]

Taken together, this military research provides strong support for the social identity proposition that aspiring leaders should cultivate and manage social identities in order to drive team individual and collective motivation and performance.[27] It does not, however, directly support the more radical message that shared social identification is a key driver of influence among military members and therefore underpins military leadership itself. Fortunately, some recent studies have sought to provide direct evidence for the role of social identification in determining the presence or absence of military leadership. For example, a longitudinal study of 218 recruit commandos in the Royal Marines undertaken over a 25-week period made the provocative finding that those individuals who thought of themselves as leaders were indeed more likely to be viewed as leaders, but only by their commanders—that is, not by their peers. In contrast, those who thought of themselves as followers were more likely to be viewed by peers as leaders and to be ‘embodying the commando spirit’.[28] In other words, focusing on one’s role as a fellow group member—as a contributor and comrade—led to more leadership attribution among those who they one day may lead.

A second study tracked the sequence of events leading up to the replacement of the commander of a Dutch reconnaissance platoon deployed in Afghanistan.[29] Despite being seen as a ‘rising star’ by more senior officers, this officer was vehemently rejected as a leader by the non-commissioned officers (NCOs) under his command. In an investigation into the cause of that failure, a rich picture emerged of someone perceived to be a platoon ‘outsider’, despite his rank and on-paper membership. He was seen to be an inexperienced ‘elite-boy’ from the military academy, who fell short in embodying local group norms and standards and was not motivated to act in the interests of the platoon. This deficiency (in being seen to be one of ‘us’) resulted in the commander’s inability to engender necessary trust and respect from the NCOs, and ultimately impeded his ability to enact a vision for the platoon. Both studies lend support to a key implication of social identity theorising: perceived in-group membership will be a critical factor in military leadership.

The findings of these military studies are echoed by an impressive amount of research in the general community, including two recent meta-analyses. The first, in 2018, looked at 35 studies (over 6,000 participants) and found strong support for the key tenet that people respond more positively to the leadership efforts of those who embody a social identity (r = 0.49).[30] The same general finding was obtained in a 2021 meta-analysis involving 128 studies (over 30,000 participants, r = 0.38).[31]

Social Identity Principles in Australian Military Practice

In a number of previous publications, using language familiar to military personnel, the second author of this paper has often shone light on the connection between social identity principles and Australian military leadership. One of those noted the importance of local social identity management, specifically for tackling diversity and inclusion challenges in the ADF.[32] Another, the recent book Leadership Secrets of the Australian Army,puts numerous links between social identity processes and Army leadership practices on display for a wide audience.[33] The next few paragraphs briefly summarise some key points from those two sources, before turning to an examination of the critical enabling role that established social identities play in Australian military leadership processes.

Local Social Identity Management

A clear implication of the social identity analysis of leadership is that those seeking to shape behaviour should aim to understand and manage social identities. That process of deliberately shaping social identities has been given several labels, including ‘identity entrepreneurship’[34] and ‘identity leadership’.[35] Whatever the terminology, the basic message is that aspiring leaders should use language, create experiences and build structures that bolster desired in-groups, while simultaneously moulding themselves so that they present as an exemplary member of the in-group(s) they seek to influence. Those efforts can be simple, e.g., facilitating the various background and foreground activities that allow the group to validly claim credit for and gain satisfaction from collective accomplishment, and spending time working with, rather than directing, the group. Of course, it will sometimes be implausible to present oneself as an exemplar in the eyes of in-group members, with visible attempts to do so often backfiring, fuelling a perception that one is an inauthentic outsider[36] and a potential threat to the standing of the in-group.[37] Under those circumstances, a better approach might be to identify and quietly support an in-group agent—someone viewed by in-group members as archetypally ‘us’—who can be trusted to align the efforts of in-group members with organisational needs.[38]

In the context of a recent ADF-wide initiative to culturally embed inclusivity, local social identity management has been described as one of the ‘old basics’ of military leadership.[39] Recognising and using the basics of social identity management is critical if the ADF realistically expects positive cultural and behavioural change (as enunciated by senior members) to penetrate to lower levels and across disparate geographies. Historical examples are plentiful. With regard to becoming an exemplary in-group member, the fundamental elements that determine the inherent professional authority of junior Australian Army officers are physical fitness, basic military and professional team skills, and looking out for and after troop welfare where one can.[40] Beyond their practical usefulness, all three characteristics are highly visible indicators of the extent to which junior officers are embracing their professional obligations, and whether they are meeting—and ideally exceeding—the performance values of the in-group (there is more on this below). In terms of in-group prioritisation and affirming narratives, the case of renowned Australian World War I Commander Harold ‘Pompey’ Elliott is illustrative. Despite having a reputation as a disciplinarian, he generated respect and affection from his subordinates that bordered on reverence. This can be explained by his patent interest in the wellbeing of the 1,000-odd men in the 7th Battalion—his in-group—and his focus on creating a narrative to explain why it should be regarded as being on par with Cromwell’s legendary Ironsides, thereby bolstering in-group standing. A more recent example—at the other end of the organisational pyramid—is former CDF Angus Houston’s deft engineering of his senior team’s physical proximity and experiences to fuel a sense of ‘us’. Houston turned around what had been a dearth of collegiality at the most senior ADF levels in several structural ways, including scheduling short periods of intense shared activity for those senior team members (i.e., workplace retreats spanning several days) and co-locating them in terms of their living environments. The collegiality turnaround was achieved remarkably quickly, entailing such a sense of equivalence among the senior leadership team that often thereafter ‘one Service chief would be prepared to argue the projects of another Service even at the expense of his own’.[41]

Leadership Secrets of the Australian Army provides many other examples of skilful social identity management in the ADF. Perhaps the clearest example is the ‘mission-team-me’ (MTM) motto, which captures a prioritisation framework firmly instilled across Army.[42] This holds that a leader’s main priority will always be the mission, after which comes the team, and only when those two sets of needs are met should leaders attend to their own needs (as in the tradition that ‘officers eat last’). By serving as a ready reminder that a group leader’s priorities are the goals and wellbeing of teams and the organisation, the MTM maxim prompts a routine practice of championing in-group values and interests, as well as of personally sacrificing for the sake of the in-group. A more subtle example is the social identity implications of the GOYA mantra. This was displayed by one Royal Australian Navy (RAN) warrant officer prominently in his office.[43] GOYA (‘get off your arse’) is a reminder to resist those factors that might trap aspiring leaders behind their desks, diligently toiling through inboxes and administration. Through GOYA, they are pushed to spend time in the broader workplace to listen to team members and, in many small ways, to share their experiences. GOYA is an effective low-key version of the axiom that one should ‘lead from the front’ and a reminder that the leadership process requires connection. The military’s standard method of issuing commands and instructions—using a standard format, with the chance for questions in the final stages of the process, and, above all, delivered face to face—also helps in this respect. The presence of commanders among subordinates helps counter the potential psychological rift that rank can cause, and shows subordinates that superiors care for the in-group, understand the in-group, and are part of ‘us’.

Leadership Culture

Clearly there are strong parallels between individual leadership practice within the ADF and the scientific insights of the social identity perspective. Not coincidentally, those individual leadership efforts also operate in line with organisational requirements and are aligned with one another. One of the great assets within the Australian military institution is its strong ‘leadership culture’, which is a professional environment where certain ‘enabling’ factors systematically operate in ways that make it easier for military members to get things done.[44] As well as the skills of aspiring leaders, leadership culture is founded on:

- followership—the willingness and ability of subordinates to collaborate and share in the leadership process where necessary

- intellectual capital—practices, procedures and ways of thinking that assist in decision-making, communication and action

- social capital—a common sense of professional identity and a common set of values, giving rise to shared understanding and cohesion across the institution.

Social identity processes play a key role in all three of these elements, with the creation of leadership culture sensibly thought of as an exercise in social identity management at an institutional level.

Both followership and social capital are driven by the presence of strong complementary organisational identities among members. As noted earlier, social identification encourages consensus and shared understanding. Within the ADF, this includes adherence to shared values and professional standards. A sense of common social identity is a strong motivator for individuals to commit to achieving in-group goals and to take the initiative, because in-group members routinely experience the achievements of the in-group as their own personal achievement. As already discussed, militaries promote organisational identification like few other types of institutions, with enormous effort and resources expended—in ways both obvious and subtle—on shared experiences and training, endorsed narratives, and official symbology and apparel (e.g., the ADF Special Air Service’s distinctive fawn/sandy beret). All of these measures help to fuel a sense of ‘us’ at both the whole-of-organisation and local levels. In this regard, the ADF has a number of advantages, not least that it can realistically promise a career for life, sometimes beginning in the mid to late teens—a career that is widely esteemed across Australian society and deeply connected with Australia’s history and folklore. The ADF enjoys considerable public respect as a past and present defender of Australian society against international threats. Such is the strength of organisational identification that former ADF members often experience significant difficulty in adjusting to civilian life.[45]

The influence of social identification in shaping ADF intellectual capital manifests in cultural content, or in-group norms. Organisational identification assists in the automatic and smooth practice of certain procedures and ways of thinking. Distinctive ways of acting and thinking—e.g., making decisions based on the Military Appreciation Process, the ‘situation, mission, execution, administration’ communication protocol, and conducting after-action reviews to learn from experience—come to be embedded in the skill sets and professional habits of ADF members; they become internalised as part of what ‘we’ do. Cultural content also prescribes accepted authority figures and sources of expertise; our organisational identities prescribe who ‘we’ listen to. Contrary to the promoted misattribution that institutions are the arbiters of authority, the reality is that ‘the determination of authority lies with the subordinate individual’.[46] Social identity insights mean that we can further refine this important message to say that the determinant of authority is the in-group that subordinate individuals identify with.[47] Said otherwise, acceptance of authority and expertise hinges on internalised group norms. Those group norms can only be expected to support ‘top down’ authority in the presence of an organisational identity that is sufficiently institutionally aligned.

A core element of military leadership culture is the concept of ‘command’. Recent RAN leadership guidance captured this well, describing how ‘Command is a term of cultural significance in the Navy. There is unquestionable dignity, honour and responsibility attached to the command of Australian officers and sailors’.[48] In short, respect for command authority is a core element of what it means to be ‘we’ military members. This is not to say that military culture results in unvaried compliance to orders on the part of subordinates. The storied history of command in operations clearly shows us that some orders will be followed enthusiastically, some grudgingly, and some not at all. Partly this is because military members apply informal criteria that determine for them what real ‘command’ looks like. Those informal criteria distinguish credible authority figures who deserve attention and regard at all times (i.e., whether delivering a formal order or not), in contrast to those who simply hold higher rank. Informal command criteria, or command stereotypes, have been described as part of the ADF’s knower code, which is informed by appraisals of individuals’ rank, organisational contributions, and tribal status. Sometimes that knower code (or ‘do as I say because of who I am’) can be exclusionary in deeply problematic ways,[49] but the knower code nonetheless provides a template for members to model themselves on. This enables new commanders who fit that template to step into roles and be immediately accepted as influential authority figures. Swift commander acceptance is indispensable not only in combat, where a commander may be killed or injured and expressly replaced, but also in coping with high-tempo posting cycles in the ADF, which typically result in job tenure of not more than two or three years. It is through organisational identification that informal beliefs and expectations, adding essential richness and potency to military command, become shared and standardised.

The current process of embedding ADF intellectual capital from the very start of an individual’s military career is a concerted investment in organisational effectiveness. It has long been routine practice for junior officer career development to begin with a strong element of intensive training aimed at mastery of basic professional military skills, with the stages of that training aligned with other rank increments. Thus the early months of army officer cadet training will include being brought to ‘private level’ in terms of soldierly skills (e.g., weapon handling, drill, field craft), before going on to be brought to ‘corporal level’, with the final preliminary stage focused on attaining the distinctive skills of the embryo infantry subaltern. Once commissioned, junior officers receive intensive training in their core function, so they join their first unit with a solid foundation of general and corps-specific skills.

The consistency of skills and understanding instilled across the ADF is itself a source of social identification, with shared expertise becoming an indicator that each individual has something important in common with others. In this way, intellectual capital exists both as an outcome of social identification and as fuel for social identification. Training not only gives the embryonic junior officer the professional basis for supervising and directing within their specialty; it also converts them into in-group members, from the perspective of both the outward observer and the officer themselves.

Summing up then, social identification processes are fundamental to ADF leadership culture. Members’ organisational identities within the ADF are crucial to building followership, intellectual capital and social capital in teams at all levels. Those three ingredients in turn serve as the platform for the leadership practices of individuals. Their ability to lead will then be heightened when actively tapping into the underlying social identity processes. This includes maintaining or strengthening their own in-group standing, or demonstrating achievements and establishing rituals that strengthen the nature of local organisational identification (achievements and rituals that range from team achievements and awards to distinctive sets of colours and designated barracks and mess areas). One further ‘take-home message’ is clear: acceptance of authority requires the maintenance of in-group norms that entail beliefs about legitimacy and expertise.[50] As a corollary, only when authority is wielded in a way that is consistent with normatively accepted in-group standards can followership, commitment or willing sacrifice be expected from military members. This assertion marries with the observation that ‘[while] formal authority invests [managers] with great potential power; leadership determines in large part how much of it they will realise’.[51]

Advancing Military Leadership

Although social identity processes are foundational to current military leadership practice in Australia on both individual and institutional fronts, the ADF’s thinking about professional practice and leadership has developed largely independently of social identity research and theory. In fact, virtually all of the tradition, symbolism and narratives concerning military leadership in Australia (and in other countries) pre-date social identity publications on the topic. The question then is: if good leadership practices can be embedded throughout a military institution without consciously applying a social identity lens, is there a need to apply that lens at all? We have two main reasons for answering in the affirmative.

First, despite their overall leadership strengths, militaries have pockets of poor practice, sometimes contributing to devastating fallout.[52] Second, given that leadership is arguably the primary professional competency within the officer corps, the military institution should routinely explore every possible avenue to improve this area of performance, even if it believes that it is already performing at a relatively high level. The social identity approach represents an opportunity to use our growing understanding of collective psychology to guide increasingly refined and reliable leadership practices.

At the organisational level, a social identity informed approach to leadership would entail shoring up the rituals, systems and messaging protocols that shape beneficial organisational identities, while at the same time correcting or disrupting those organisational identities that have the potential to cause harm. At the individual level, it would mean developing servicemen and servicewomen who have both the awareness and the skill needed for shaping local social identities. The aim would be to improve the ability of those individuals to curate organisational identification by the use of shared experiences, behavioural expectations, and stories, all in a manner aligned to institutional initiatives.

Advancing military leadership using social identity insights will require appreciation by militaries that a significant part of their renowned strength in leadership is the inadvertent result of deeply embedded and long-established practices. A primary example of this is the aforementioned requirement for those being prepared for junior officership to begin their developmental process by learning and mastering the core competencies within their particular arena of professional practice. When successful, not only does the process enhance their capability in supervising and managing but it also establishes mannerisms and ways of working, and a familiar persona, that make junior officers recognisable to their soldiers as someone like ‘us’. Understanding the social identity benefit of becoming expert in the skills practised by one’s subordinates will almost certainly deepen and enhance those junior officers’ understanding of the nuances of ‘good leadership behaviour’.

The social identity understanding of military leadership can also be used to puncture pervasive leadership myths that often inhibit military members’ practice of effective leadership. One such myth is that leadership potential is a stable characteristic in individuals, and that true leaders thus need spend little time on further improving their thinking about and performance of leadership or adapting it in markedly different circumstances. Based on robust and highly edifying discussions held with students on the ACSC, 2016 to 2022, we believe that the myth of inherent leadership capacity is particularly important to debunk.

Military Leadership beyond Individual Capacity

Reflecting on his career, retired Major General John Cantwell admitted frankly that ‘I used to think that [leadership] was about me, rather than the people I was trying to lead’ (original emphasis).[53] His observation neatly encapsulates the stark contrast between widespread beliefs about the nature of leadership and the science of leadership. The individualistic mythology of leadership introduced earlier revolves around the notion that leadership is a characteristic of certain people. That mythology drives aspiring leaders like the young Cantwell to think that leadership is fundamentally about them, even though serious scholarship has long been pushing for the rejection of that leader-centric perspective.[54] The social identity approach is especially well suited for countering the individualist myth because it reveals precisely why aspiring leaders should attend closely to how they are perceived by the people they seek to influence, and how those same people perceive themselves and their place in the organisation. This is consistent with the oft-used adage that the least important word in leadership vernacular is ‘I’.[55] This is not to say that an individual’s characteristics are unimportant in leadership, but that such qualities and characteristics are important only in the context of the perspectives of others.

Those operating with an individualistic perspective on leadership will miss this, often with serious consequences. To begin with, that perspective can blinker us to personal achievements and personal self-development. A number of ACSC students reported such self-interest among peers and former superiors, going on to describe how those self-interested officers come to view colleagues and team members essentially as resources that exist only to be deployed in service of their personal ambition. Further, because others are ‘mere resources’ rather than respected colleagues, that aspiring leader will tend to attribute any encountered frictions, or resistance to their vision, to the shortcomings or mal-intent of their colleagues/teams. That resistance is then met with disdain and punitive responses, breeding conflict throughout the organisation. This article’s second author has also observed in the Australian Army a syndrome where individualism in the language of leadership supports the prevalence of egocentric careerism, exactly along the lines described above.[56] Similar concerns have been raised about the US military.[57] Individualistic leaders can be expected to exhibit little motivation to consider their own limitations or to consider potential deficiencies in the existing leadership culture.

A commander who self-centeredly pursues aggrandisement and short-term success at the expense of long-term capability and the wellbeing of subordinates is displaying the very essence of narcissism. This is the threat in a nutshell. Organisations whose members believe that leadership fundamentally emanates from certain individuals risk attracting narcissists, or entrenching narcissism throughout their ranks.[58] Although the social identity approach does not deny the value of conceptualising oneself as a leader or taking pride in oneself as such, it does make the strong—and nominally paradoxical—case that a narrowed emphasis on enhancing oneself as a leader can be a hindrance to the practice of leadership. In reality, the effectiveness of any individual or group seeking to lead will crucially depend on whether their conceptualisation of leadership emphasises the importance of understanding in-groups, shaping in-groups in ways that promote performance, and maintaining one’s relationship with in-groups.[59]

While individualism can lead those with initial leadership confidence down a path of self-centeredness and indifference, those lacking in confidence may also be deterred from taking on leadership opportunities in the first place. If, for whatever reason, one has struggled to lead in the past, the individualist may attribute that to relatively stable characteristics of oneself, resulting in reduced confidence regarding one’s leadership potential. The danger here occurs when aspiring leaders place emphasis on having certain kinds of abstract ‘leadership qualities’. Any perception that one is not seen as ‘charismatic’ or ‘inspiring’, for instance, can instil the (mistaken) belief that one can never be influential and is ‘lacking leadership material’, which in turn will discourage one from pursuing opportunities to lead. This parallel effect of individualistic thinking—of writing oneself off as a leader—is more insidious than the relatively visible symptom of arrogant and abrasive, and consequently ineffective, leadership. In this way, militaries are robbed of ever seeing the true leadership potential of all of their members. This realisation should be particularly saddening in light of evidence that women and ethnic minorities face a stacked deck when given leadership opportunities.[60] It may well be the case that diverse military members have hostile and ultimately unsuccessful leadership experiences due to damagingly narrow ideas about what a leader looks like, only to internalise that experience as the absence of their own leadership potential.

Fortunately the social identity approach can serve as a treatment for the potential damage of individualistic thinking about leadership. Part of that treatment is the specific research findings that dismantle some of the specific intuitions that emerge from those traditional modes of thinking. For example, experimental evidence has provided a fresh perspective on charisma, by showing that charisma, far from being an enduring characteristic of certain people with high leadership potential, can be generated by increasing one’s in-group credentials.[61] Explaining this process has often given marked relief to ACSC students who had previously attributed their own difficult and demoralising leadership experiences to a degree of lacking ‘the right stuff’. This is not to say that the actions or characteristics of a leader are unimportant; the social identity approach places substantial importance on what aspiring leaders do, and who they are. Leadership credibility is determined by meeting the particular standards and expectations of potential followers, not by qualities of the individual in their own right.

Looking Forward

Table 1 provides a summary of what we consider to be the key concepts and central messages herein. Perhaps the most important message that readers should take from this article is to understand that a) the social identity approach provides a coherent and precise account of the psychology of emergent group influence (a.k.a. ‘leadership’) in militaries, and b) social identity processes are the psychological root of military consensus about the way things should be done and which sources of authority are legitimate. This psychological perspective is supported by a vast body of empirical research, with an increasing number of studies being conducted in military settings. The role of social identities in leadership practice is also clearly apparent in the leadership actions of ADF members, as is its role within institutionalised Australian leadership enablers. The existing alignment is so strong that local social identity management could be reasonably described as ‘common sense best practice’.[62] Yet limited appreciation of the insights of social identity scholarship means that ADF leadership is still hit-and-miss when it comes to utilisation of social identity processes. This article touched on two critical ongoing leadership failings: regular instances of self-absorbed/self-interested leadership, and self-defeating beliefs about the stability of personal leadership ability. As demonstrated, these limitations are underpinned by myths that are debunked by the social identity approach.

Instilling a thorough practical understanding of social identity processes within military organisations could occur through training, education, and tools for practice. Current efforts along those lines are regrettably few. Mid-career ACSC students, whether from the ADF or among ACSC’s international participants,[63] have often commented to the first author that they have never previously been exposed to perspectives on leadership that address the collective psychology of followers. Students have also commonly reported that exposure to social identity ideas gave them newfound insight into the patterns of influence, social power and intergroup relations that they have witnessed over their careers. OneRAN officer, for example, recalled puzzlement when watching colleagues paint red paw prints on the companionway leading up to the bridge of the Anzac-class frigate they were serving on. At the time, that officer saw the activity as childish and unprofessional and couldn’t understand why it was not only looked on favourably by their shipmates but was also endorsed by the ship’s captain. It was only after studying the role of symbols in instilling a sense of identity, and the particular potency of social identities with unique features, that this officer came to understand the identity and morale building value of visually associating HMAS Perth (III) with the esteemed history of HMAS Perth (I). The latter ship had seen extensive combat service during World War II, eventually to be lost during battle in the Pacific, and those red paw prints were a nod to the ship’s cat of HMAS Perth (I), which had once spilled and trodden red paint across the paint locker and left an incriminating trail. That officer’s candid reflections indicate clearly how common sense best practice could be lost, and operational effectiveness compromised, by failing to understand the nature of social identity processes.

About the Authors

Dr Andrew Frain completed his PhD in social psychology at the Australian National University. His research interests centre on the social identity approach and science integrity, with particular interest in research translation. Andrew has worked in the Australian Department of Defence Directorate of People Intelligence and Research, and was the convenor of the Australian War College ACSC Leadership Theory module from 2016 to 2022. Andrew would typify one of Michael Billig’s ‘antiquarian psychologists’, always drawn to the dustiest corner of the library.[64]

Nick Jans’s career began conventionally enough, with the Royal Military College (Duntroon) followed by regimental service in Vietnam. But after that it was distinctively unconventional, as he rotated between internal consultancy, research and policy roles, all guided by the longstanding principle that ‘There is nothing as practical as a good theory’. After 25 years of regular service, he then spent nearly as long in the Reserves. In the meantime, after a few years at the University of Canberra, he moved to full-time consultancy. He was able to put his ideas on leadership into practice in his adopted hometown of Marysville after the 2009 Black Saturday bushfires, for which he was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the students who attended the Australian Command and Staff Course over the years 2016 to 2022. It is a rarity to find such a knowledgeable, experienced and engaged body of individuals, and a privilege to intellectually challenge these students and to be challenged in turn. We are also indebted to the Australian Department of Defence and Australian National University support staff of that program. We the authors report no potential conflict of interest.

NOTE: Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Andrew J Frain, The Australian National University, Canberra.

Email: Andrew.Frain@anu.edu.au

Phone: +614 1280 3498.

Table 1: The social identity perspective on the psychology of leadership

|

The Social Identity Approach |

||

| Meta-theoretical Foundation | Collectives (e.g., societies, cultures, groups) are a reality, not shared illusions, and collectives are indispensable to what it means to be an individual | |

| Central Concepts |

Social identity—Our sense of ourselves as being a member of an in-group (e.g., ‘we Australians’) Organisational identity—A social identity shaped by organisational membership (e.g., ‘we Army’) |

|

| Implications for Leadership |

Social identification fuels motivation to pursue collective goals Social identification fuels motivation to contribute ideas and to consider the ideas of fellow in-group members All else equal, those who best exemplify the in-group hold the most influence among in-group members In-group norms determine who members recognise as sources of expertise or as legitimate authorities |

|

| Messages for Military Practice | For Individuals | For Institutions |

|

Bolster a local sense of ‘us’ through language, experiences and structures Personally embody what it means to be ‘us’ - Or - Leverage the influence of those who embody local organisational identities |

Foster organisational identities that support mission success, and treat or disrupt those that don’t Train individuals to be skilled identity entrepreneurs, able to shape and navigate local organisational identities |

|

A response to this article by Anne Goyne

Author comment to the response

Endnotes

[1] A King, The Combat Soldier: Infantry Tactics and Cohesion in the Twentieth and Twenty-first Centuries (Oxford University Press, 2013).

[2] Despite over 40 years of subsequent intensive research activity, the ongoing dissensus among leadership theorists suggests that leadership remains ‘one of the most observed and least understood phenomena on earth’. JM Burns, Leadership (Harper & Row, 1978), p. 4.

[3] SA Haslam, Psychology in Organizations (Sage, 2004).

[4] H Tajfel, ‘Social Identity and Intergroup Behaviour’, Social Science Information 13, no. 2 (1974): 65–93; H Tajfel and JC Turner, ‘An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict’, in WG Austin and S Worchel (eds), The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations (Chicago: Nelson-Hall, 1979), pp. 7–24.

[5] JC Turner, ‘Social Categorization and the Self-Concept: A Social Cognitive Theory of Group Behavior’, in EJ Lawler (ed.), Advances in Group Processes: Theory and Research (Greenwich: JAI Press, 1985), 77–122.

[6] H Tajfel, ‘Cognitive Aspects of Prejudice’, Journal of Biosocial Science 1, no. S1 (1969): 173–191; H Tajfel, Differentiation between Social Groups: Studies in the Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations (London: Academic Press, 1978).

[7] AW Staats, Psychology’s Crisis of Disunity: Philosophy and Method for a Unified Science (New York: Praeger, 1983).

[8] JC Turner and PJ Oakes, ‘The Significance of the Social Identity Concept for Social Psychology with Reference to Individualism, Interactionism and Social Influence’, British Journal of Social Psychology 25, no. 3 (1986): 237–252.

[9] This continental pattern has not always been present, and there are many exceptions. For example, Sigmund Freud’s individualistic psychoanalytic theory can be contrasted with Harry Stack Sullivan’s psychiatry. For Sullivan, social psychology’s role is to understand the reality that ‘man is the human animal transformed by social experience into a human being’. M Billig, Social Psychology and Intergroup Relations (Academic Press, 1976), pp. 96–102. See also HS Sullivan, Conceptions of Modern Psychiatry (Norton & Company, [1939] 1953), p. 31.

[10] S Reicher, ‘Politics of Crowd Psychology’, The Psychologist 4 (1991): 487–491; S Reicher and SA Haslam, ‘Why Not Everyone Is a Torturer’, BBC News, at: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/magazine/3700209.stm (accessed 10 May 2004).

[11] JM Bartels, ‘The Stanford Prison Experiment in Introductory Psychology Textbooks: A Content Analysis’, Psychology Learning & Teaching 14, no. 1 (2015): 36–50; S Reicher and SA Haslam, ‘Towards a “Science of Movement”: Identity, Authority and Influence in the Production of Social Stability and Social Change’, Journal of Social and Political Psychology 1, no. 1 (2013): 112–131.

[12] G Gemmill and J Oakley, ‘Leadership: An Alienating Social Myth?’, Human Relations 45, no. 2 (1992): 113–129.

[13] The naming convention for the perspective, great man, reflects the highly marginalised status of women in society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. T Carlyle, On Heroes, Hero-worship, and the Heroic in History (The Echo Library, [1840] 2007).

[14] Tajfel, ‘Cognitive Aspects of Prejudice’.

[15] JC Turner and KJ Reynolds, ‘The Story of Social Identity’, in T Postmes and NR Branscombe (eds), Rediscovering Social Identity (Psychology Press, 2010), pp. 13–32.

[16] GA Akerlof and RE Kranton, ‘Identity Economics: How Our Identities Shape Our Work, Wages, and Well-being (Princeton University Press, 2010), p. 45.

[17] JC Turner, ‘Toward a Cognitive Definition of the Group’, in H Tajfel (ed.), Social Identity and Intergroup Relations (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982), pp. 15–40; JC Turner, ‘A Self-Categorization Theory’, in JC Turner, MA Hogg, P Oakes, S Reicher and MS Wetherell (eds), Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-Categorization Theory (Oxford: Blackwell, 1987), pp. 42–67.

[18] JC Turner and SA Haslam, ‘Social Identity, Organisations, and Leadership’, in ME Turner (ed.), Groups at Work: Theory and Research (London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2001), pp. 25–65; SA Haslam, SA Reicher and MJ Platow, The New Psychology of Leadership: Identity, Influence and Power, 2nd Edition (Psychology Press, 2020).

[19] D Al Raffie, ‘Social Identity Theory for Investigating Islamic Extremism in the Diaspora’, Journal of Strategic Security 6, no. 4 (2013): 67–91; SD Reicher and SA Haslam, ‘Fueling Extremes’, Scientific American Mind 27, no. 3 (2016): 34–39.

[20] MJ Platow, M Durante, N Williams, M Garrett, J Walshe, S Cincotta, G Lianos and A Barutchu, ‘The Contribution of Sport Fan Social Identity to the Production of Prosocial Behavior’, Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice 3, no. 2 (1999): 161.

[21] N Jans, Leadership Secrets of the Australian Army: Learn from the Best and Inspire Your Team for Great Results (Allen & Unwin, 2018).

[22] Haslam, Reicher and Platow, The New Psychology of Leadership.

[23] B Shamir, E Zakay, E Brainin and M Popper, ‘Leadership and Social Identification in Military Units: Direct and Indirect Relationships’, Journal of Applied Social Psychology 30, no. 3 (2000): 612–640. See also B Shamir, E Brainin, E Zakay and M Popper, ‘Perceived Combat Readiness as Collective Efficacy: Individual- and Group-level Analysis’, Military Psychology 12, no. 2 (2000): 105–119.

[24] RB Johansen, JC Laberg and M Martinussen, ‘Military Identity as Predictor of Perceived Military Competence and Skills’, Armed Forces & Society 40, no. 3 (2014): 521–543.

[25] VC Franke, ‘Duty, Honor, Country: The Social Identity of West Point Cadets’, Armed Forces & Society 26, no. 2 (2000): 175–202.

[26] J Griffith, ‘Being a Reserve Soldier: A Matter of Social Identity’, Armed Forces & Society 36, no. 1 (2009): 38–64.

[27] N Ellemers, D De Gilder and SA Haslam, ‘Motivating Individuals and Groups at Work: A Social Identity Perspective on Leadership and Group Performance’, Academy of Management Review 29, no. 3 (2004): 459–478.

[28] K Peters and SA Haslam, ‘I Follow, Therefore I Lead: A Longitudinal Study of Leader and Follower Identity and Leadership in the Marines’, British Journal of Psychology 109, no. 4 (2018): 708–723.

[29] MM Jansen and R Delahaij, ‘Leadership Acceptance through the Lens of Social Identity Theory: A Case Study of Military Leadership in Afghanistan’, Armed Forces & Society 46, no. 4 (2020): 657–676.

[30] NB Barreto and MA Hogg, ‘Evaluation of and Support for Group Prototypical Leaders: A Meta-analysis of Twenty Years of Empirical Research’, Social Influence 12 (2017), 41–55.

[31] NK Steffens, KA Munt, D van Knippenberg, MJ Platow and SA Haslam, ‘Advancing the Social Identity Theory of Leadership: A Meta-analytic Review of Leader Group Prototypicality’, Organizational Psychology Review 11, no. 1 (2021): 35–72.

[32] N Jans, New Values, Old Basics: How Leadership Shapes Support for Inclusion (Centre for Defence and Strategic Studies, Australian Defence College, 2014).

[33] Jans, Leadership Secrets.

[34] SA Haslam, T Postmes and N Ellemers, ‘More Than a Metaphor: Organisational Identity Makes Organisational Life Possible’, British Journal of Management 14, no. 4 (2003): 357–369.

[35] NK Steffens, SA Haslam, SD Reicher, MJ Platow, K Fransen, J Yang, MK Ryan, J Jetten, K Peters and F Boen, ‘Leadership as Social Identity Management: Introducing the Identity Leadership Inventory (ILI) to Assess and Validate a Four-dimensional Model’, The Leadership Quarterly 25, no. 5 (2014): 1001–1024.

[36] NK Steffens, F Mols, SA Haslam, TG Okimoto, ‘True to What We Stand for: Championing Collective Interests as a Path to Authentic Leadership’, The Leadership Quarterly 27, no. 5 (2016): 726–744.

[37] JM Marques, ‘The Black Sheep Effect: Out-group Homogeneity in Social Comparison Settings’, in D Abrams and MA Hogg (eds), Social Identity Theory: Constructive and Critical Advances (Springer-Verlag, 1990), pp. 131–151.

[38] While the use of in-group agents for the purposes of military leadership may at first glance seem Machiavellian, it is common practice. The non-commissioned officer model is argued by Etzioni to be an institutionalised instantiation of that technique. A Etzioni, A Comparative Analysis of Complex Organizations, Revised and Enlarged Edition (The Free Press, 1975), p. 175.

[39] Compare with E Gosling, ‘The Role of the Officers’ Mess in Inclusive Military Leader Social Identity Construction’, Leadership 18, no. 1 (2022): 40–60.

[40] Jans, New Values, p. 10. See also C Masters, Uncommon Soldier: Brave, Compassionate and Tough, the Making of Australia’s Modern Digger (Allen & Unwin, 2012), p. 71.

[41] Jans, New Values, p. 9; N Jans, S Mugford, J Cullens and J Frazer‐Jans, The Chiefs: A Study of Strategic Leadership (Australian Defence College, 2013), p. 13.

[42] Jans, Leadership Secrets, p. 51.

[43] Jans, Leadership Secrets, p. 93.

[44] N Jans, It’s the Backswing, Stupid: The Essence of Leadership Culture in Military Institutions (Centre for Defence Leadership & Ethics, Australian Defence College, 2006).

[45] M Kreminski, M Barry and M Platow, ‘The Effects of the Incompatible “Soldier” Identity upon Depression in Former Australian Army Personnel’, Journal of Military and Veterans Health 26, no. 2 (2018): 51–59.

[46] CI Barnard, The Functions of the Executive (Harvard University Press, 1938), p. 167.

[47] JC Turner, KJ Reynolds and E Subasic, ‘Identity Confers Power: The New View of Leadership in Social Psychology’, in P Hart and J Uhr (eds), Public Leadership (Canberra: ANU Press, 2008), pp. 57–72.

[48] Sea Power Centre, The Royal Australian Navy Leadership Ethic (Australian Department of Defence, 2010), p. 57.

[49] E Thomson, Battling with Words: A Study of Language, Diversity and Social Inclusion in the Australian Department of Defence (Australian Department of Defence, 2014).

[50] JC Turner, ‘Explaining the Nature of Power: A Three-Process Theory’, European Journal of Social Psychology 35, no. 1 (2005): 1–22.

[51] H Mintzberg, ‘The Manager’s Job: Folklore and Fact’, in RP Vecchio (ed.), Leadership: Understanding the Dynamics of Power and Influence in Organizations (University of Notre Dame Press, [1975] 1997), p. 43.

[52] For example, Inspector-General of the Australian Defence Force, Afghanistan Inquiry Report (Australian Department of Defence, 2021).

[53] J Cantwell, Leadership in Action (Melbourne University Press, 2015), p. 13.

[54] CA Gibb, ‘The Principles and Traits of Leadership’, The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 42, no. 3 (1947): 267–284; Burns, Leadership.

[55] JE Adair, John Adair’s 100 Greatest Ideas for Effective Leadership and Management (Capstone, 2002), p. 44.

[56] N Jans, ‘Shared Leadership and the Strategic Corporal Metaphor: Some Considerations’, in D Lovell and DP Baker (eds), The Strategic Corporal Revisited: Challenges for Combatants in 21st-century Warfare (Juta and Company, 2017), pp. 19–31.

[57] DR Lindsay, DV Day and SM Halpin, ‘Shared Leadership in the Military: Reality, Possibility, or Pipedream?’, Military Psychology 23, no. 5 (2011): 528–549.

[58] In line with this proposition, recent research has found that leadership theories, particularly those theories that are individualistic, disproportionately attract those who are more narcissistic. NK Steffens and SA Haslam, ‘The Narcissistic Appeal of Leadership Theories’, American Psychologist 77, no. 2 (2022): 234–248.

[59] SA Haslam, AM Gaffney, MA Hogg, DE Rast III and NK Steffens, ‘Reconciling Identity Leadership and Leader Identity: A Dual-Identity Framework’, The Leadership Quarterly 33, no, 4 (2022): 1–15.

[60] For example, AS Rosette, GJ Leonardelli and KW Phillips, ‘The White Standard: Racial Bias in Leader Categorization’, Journal of Applied Psychology 93, no. 4 (2008): 758–777; MK Ryan and SA Haslam, ‘The Glass Cliff: Evidence That Women Are Over‐Represented in Precarious Leadership Positions’, British Journal of Management 16, no. 2 (2005): 81–90; VE Schein, R Mueller, T Lituchy and J Liu, ‘Think Manager—Think Male: A Global Phenomenon?’, Journal of Organizational Behavior 17, no. 1 (1996): 33–41.

[61] MJ Platow, D Van Knippenberg, SA Haslam, B Van Knippenberg and R Spears, ‘A Special Gift We Bestow on You for Being Representative of Us: Considering Leader Charisma from a Self‐Categorization Perspective’, British Journal of Social Psychology 45, no. 2 (2006): 303–320.

[62] Jans, New Values, p. 9.

[63] Each year the international guest participants on the ACSC come from upward of 20 different overseas militaries, including representation from Western nations (e.g., Canada, Germany, USA) and non-Western nations (e.g., Korea, Pakistan, Sri Lanka).

[64] M Billig, Arguing and Thinking: A Rhetorical Approach to Social Psychology (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987), p. 1.

Response to Article

Author of Response: Anne Goyne

Social identity theory explains how group identity, and its associated status, is internalised to become part of an individual’s personal identity.[1] According to the theory, the stronger the sense of group identification the stronger the sense of belonging, and the stronger the sense of difference from outsiders. The terms in-group and out-group describe the bias that can evolve from this phenomenon, explaining why people behave more positively to members of their in-group and more negatively to ‘others’. Social identity theory differs from self-categorisation theory in that the latter explains the different categories a person may ascribe to themselves, such as wife, mother, friend, whereas their social identity reflects their in-group membership, at least according to the theory. In ‘The Social Identity Foundations of Military Leadership’, the authors refer to a hybrid construct the social identity approach, an umbrella term used in research to investigate how group identification and self-categorisation can promote behaviour change.[2]

The most obvious example of social identity theory in action is military training. Military ab initio training develops a strong in-group social identity among new recruits. This sense of an in-group develops strong pro-social military virtues, such as in-group loyalty, obedience to authority, and self-sacrifice in the face of danger. Each service has its own ab initio training to instil a deep sense of service identity. By contrast, ab initio officer training is entirely separate from recruit training, intentionally segregating officers and enlisted personnel. Officers are encouraged to develop themselves intellectually, to question what is going on around them, to be curious and, in many ways, to maintain greater individuality. The segregation between officers and enlisted personnel has a long history and reflects the role played by commanders who sit in judgement over their followers.[3]

According to the authors, this sense of ‘individualism’ among officers is causing a serious problem in the ADF. They believe that many officers ascribe to the ‘great man’ theory of leadership—that is, that the only good leaders throughout history have been upper-class, heterosexual Anglo Saxon men. For decades, officer training in the ADF reinforced this view by focusing almost exclusively on the leadership of men like Napoleon, Churchill, Eisenhower and MacArthur, all exemplars of the ‘great man’ model. Perhaps to address complaints of bias, Australian Command and Staff College no longer includes the study of great leaders as part of its leadership program. This decision, while understandable, also prevents any chance of dispelling the myth.

Indeed, if the prevalence of the ‘great man’ theory (and all the poor leadership the authors refer to) is a true reflection of ADF leaders, we as an institution have a serious problem. Those who ascribe to this idea often harbour discriminatory views about women, social class, sexuality and race. The authors argue that the social identity approach could help overcome the problem of narcissistic, careerist, individualist leaders[4] by breaking down individualism and inculcating a greater sense of identification with followers and/or the institution.

When I first reviewed this paper, I had doubts about the value of social identity as a means of cultural change, largely because social identity was the obvious cause, but I have had a chance to reflect. The authors have raised a serious issue that sits at the heart of ADF culture: how we manufacture the social identity of the people who join. By design, officers have greater privilege and status in the ADF while enlisted personnel learn they belong to a different class and must pay deference to those with the King’s Commission. This social demarcation reflects a typically British social class divide, which may no longer be appropriate in modern Australia. Moreover, if this approach is leading to maladapted thinking and behaviour about the right of some individuals to dominate others, it no longer reflects the ADF’s own philosophy of leadership.

The social identity approach may provide a way forward, but accepting the premise of this paper without investigation would be a disservice to ADF officers generally. We need to understand if such a problem really exists, and whether the ADF needs to overhaul yet another cultural tradition—the class segregation of officers and enlisted personnel. This is a huge question, but perhaps the time has come to have this discussion.

About the Commentator

Anne Goyne is the senior research psychologist at the Centre for Defence Leadership and Ethics (CDLE), Australian Defence College. She has served for 42 years as a military psychologist, both in uniform and civilian roles. Anne has been joint editor on two books relating to military stress and performance and has published over 45 articles and reports. At CDLE, she is responsible for applied psychological research in leadership, ethics and human behaviour and is a frequent lecturer across Defence.

Author Comment to Response

Endnotes

[1] J Turner and P Oakes, ‘The Significance of the Social Identity Theory Concept for Social Psychology with Reference to Individualism, Interactionism and Social Influence’, British Journal of Social Psychology 25, no. 3 (1986): 237–252.

[2] All words used in the paper—see p. 15.

[3] M Stevens, T Rees, P Coffee, N Steffens, SA Haslam and R Polman, ‘A Social Identity Approach to Understanding and Promoting Physical Activity’, Sports Medicine 47, no. 10 (2017): 1911–1918, doi: 10.1007/s40279-017-0720-4.

[4] Almost identical to the Qadi in Islam, a system of social judgement dating back millennia.

Comments on Response to Article

Authors: Andrew J Frain and Nicholas Jans

We appreciate Anne Goyne’s having taken the time to provide commentary on our paper. We are also grateful for her deep engagement as a reviewer. Her comments, along with the contributions of other reviewers, the Australian Army Journal editorial team and our own friends and family made a material difference to the clarity and accessibility of our arguments.

In her commentary Anne has zeroed in on our analysis of poor leadership performance and damaging leadership behaviours. Other readers may have the same focus, especially those who are similarly concerned about ensuring that the ADF performs to expectations and is not exposing ADF members to unjustifiable harm. Although we wholeheartedly endorse this line of analysis, we would again caution readers against playing into the widespread demonising of the psychology of groups and belonging. As we discuss in our paper, mainstream psychological perspectives too often fail to appreciate that social identity processes are just as important to excellence and high performance as they are in any substandard performance or catastrophe. Central to our message is that the great feats of the ADF, and militaries the world over, are only possible because of the generally effective management of the organisational identities that sustain those institutions. Further, if one seeks high levels of military effectiveness in the future, increasingly sophisticated cultivation and management of organisational identities will be required throughout the ADF.

We would clarify that we do not believe that ADF officers subscribe to the ‘great man’ approach to understanding leadership, as articulated by philosophers of early last century. Anne is correct, however, to highlight that we are concerned that military members of all ranks risk being led astray by an individualistic understanding of leadership. That individualistic lens has its origins in great man writing, but the modern incarnations have a different outward appearance (e.g. many personality trait and transformational leadership narratives). We do believe that leadership individualism distracts from the critical task of curating the organisational identities that are so crucial for military performance, and may also cause ADF members to be egocentric in their conduct.

Anne goes on to raise her own concerns about the longstanding and widely accepted divide between non-commissioned officers (NCOs) and commissioned personnel. We agree that this element of ADF structure will have significant implications for organisational identities within the military, and consequently the way that ADF members treat each other. The ADF, like many other militaries, maintains a strict intergroup status differential, based largely on the rationale that the NCO and commissioned ranks reflect distinct capabilities. Whether that structure can be sustained as an asset for the ADF will depend on a vast number of factors, and coming to a position on that question is beyond the scope of our analysis. What we can say with confidence, however, is that appreciating the social identity processes at play is vital. For example, is the added organisational partition important for generating strong local team identification?[1] Is it important to internalise different ways of working via distinct organisational identities (e.g. the way that ‘we’ NCOs act and think)? Is there a superordinate organisational identity that helps legitimise among members the low permeability between NCOs and commissioned ranks? These and many other questions, rooted in a social identity analysis, are ripe for investigation.

On that note, we would conclude by encouraging readers who wish to further understand the social identity approach to be wary of their choice of source. The social identity approach runs against the grain of mainstream psychology, and the ideas are frequently misrepresented in that literature.[2] The book The New Psychology of Leadership, listed as recommended reading in the current ADF leadership doctrine, would be one recommended starting point.[3]

Article (top)

Response to Article

Endnotes

[1] There is evidence that more abstract organisational identities are harder to sustain. D van Knippenberg and ECM van Schie, ‘Foci and Correlates of Organizational Identification’, Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 73, no. 2 (2000): 137–147; M Riketta and RV Dick, ‘Foci of Attachment in Organizations: A Meta-analytic Comparison of the Strength and Correlates of Workgroup Versus Organizational Identification and Commitment’, Journal of Vocational Behaviour 67, no. 3 (2005): 490–510.

[2] C McGarty, ‘Social Identity Theory Does Not Maintain That Identification Produces Bias, and Self-Categorization Theory Does Not Maintain That Salience Is Identification: Two Comments on Mummendey, Klink and Brown’, British Journal of Social Psychology 40, no. 2 (2001): 173–176; JC Turner and KJ Reynolds, ‘The Social Identity Perspective in Intergroup Relations: Theories, Themes, and Controversies’, in R Brown and S Gaertner (eds), Blackwell Handbook of Social Psychology: Intergroup Processes (Blackwell, 2001), pp. 133–152.

[3] SA Haslam, SA Reicher and MJ Platow, The New Psychology of Leadership: Identity, Influence and Power, 2nd Edition (Psychology Press, 2020).