Abstract

Counter-nation networks pose a serious threat to national sovereignty. How nations cope with these complex adaptive systems within the global system represents one of the most serious challenges faced by nation-states. This article will discuss the elements that comprise a complex adaptive system and suggest a counter-system approach through which they can be defeated as part of a national security strategy. A systems-based approach is the only effective way to manage and defeat these counter-nation networks that continue to threaten national sovereignty in an environment where non-state actors are capable of rivalling nation-states in their ability to influence regional and global security.

All religions, arts and sciences are branches of the same tree.

- Albert Einstein1

Introduction

The nature of war does not change, merely the character.2 So says Clausewitz in his classic work, On War. As any reader of this timeless work knows, Clausewitz’s spectrum of study is bounded at one end by ‘total war’—that is, a war of complete annihilation and utter destruction (where violence is the logic, rather than a method)—through to ‘war amongst the people’—where politics and violence by a dominant actor either inside or outside a declared state-sanctioned conflict determines the societal state in which the majority of people submit themselves.

Today’s new security order3 spans Clausewitz’s spectrum via a multitude of manifestations—conflict, war, terrorism, people smuggling, transnational crime and insurgency, to name but a few. All are connected via networks and systems constantly framing and reframing themselves as they seek to achieve an outcome whereby their prevailing existential paradigm becomes the dominant behaviour or condition. This is where victory or success is declared and a new order is imposed by the superior narrative.

How nations cope with ‘counter-nation networks’—that is, those complex adaptive systems within the global system that threaten national sovereignty—is a difficult question to ponder. How do nation-states, bounded by their Constitutions and an adherence to a ‘rule-of-law’, defeat counter-nation networks, who, by contrast, are free to constantly reframe themselves until they achieve the dominant narrative? This article will discuss the elements that comprise a complex adaptive system and suggest a counter-system approach through which they can be defeated as part of a national security strategy.

A complex adaptive system is a dynamic network of agents that act in parallel, constantly framing and reframing in reaction to the external environment. Its control is highly dispersed and decentralised. Its behaviour arises from competition and cooperation. There is little to no control— the collective action of the complex adaptive system is a result of a near infinite number of decisions made concurrently by the constituent agents from which it is comprised.

A complex adaptive system is a dynamic network of agents that act in parallel, constantly framing and reframing in reaction to the external environment.

There are a variety of counter-nation complex adaptive systems that meet the definition as described above: global terror groups, transnational people smuggling syndicates, regional based insurgencies, and criminal patronage networks such as drug smugglers and organised crime. The ways in which these systems evolve is based on three common principles: order is emergent (as opposed to pre-determined), history is irreversible, and the future is unpredictable.4

Principle 1: Order Is Emergent

Rather than being planned or controlled, a counter-nation complex adaptive system interacts in the world in order to form patterns, which informs its behaviour, constantly improving its efficiency over time to achieve its aims and objectives. An example of this is the current Taliban insurgency in Afghanistan, which did not arise from a deliberate, pre-planned and articulated strategic plan; rather, it is generated out of a loosely unified religious order that has since adapted into its current form as a counter-nation network. Throughout the past ten years its order has resulted predominantly from the pressure applied against it by the forces of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation and the Western-backed government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. This emergent, ordered pattern of behaviour has influenced it into a constantly amorphous structure, making it very difficult to target, let alone defeat.

Principle 2: History is Irreversible

All counter-nation complex adaptive systems exist within their own evolutionary environment. They germinate from somewhere. They have a base narrative. As their environment has changed, so have they. While these systems have evolved, they nonetheless are required to constantly assess their past and present in order to inform their future. Examples of these systems include the Irish Republican Army’s transition from a predominantly militant organisation into a political (Sinn Fein) and criminal organisation. History roots it in Northern Ireland and the Catholic enclaves within that country. This is undeniable. It will not change.

In understanding these systems, it is imperative to acknowledge where these systems are conceptually rooted and how they evolve. This gives it a self-generated ‘learning loop’ from which it can exponentially increase its rate of emergence, as described in the first principle.

Principle 3: The Future Is Unpredictable

As a complex adaptive system organises, it creates a multitude of competing, complimentary and counter-intuitive ‘alternatives’ from which it will derive its ‘future’. This allows the system to employ the maximum amount of variety and creativity in securing its destiny, whatever that may be. An optimal system exists on the edge of ‘chaos’; it is here where its ability to choose alternative futures is optimised, informed by a knowledge network that is generating a vast array of possibilities and alternatives. An example of a counter-nation complex adaptive system at the edge of chaos is an improvised explosive device (IED) network such as those seen most recently in Iraq and Afghanistan. The evolution of this asymmetric, low cost, high-pay off capability is developed from an environment where the enemy network had to generate a capability against a counter-system that was conventionally superior in almost every way. As a result of an urgent need to apply this asymmetry to combat this threat, the IED networks (derived from counternation terrorist groups such as al-Qaeda) evolved at an ever increasing cycle that eventually generated a tempo superior to that of their adversary, resulting in a capability overmatch. Thus, in the wars of Afghanistan and Iraq, the IED became the insurgent weapon of choice, largely due to its rate of adaption and evolution in contrast to US and allied attempts to keep up with this network through increases in force protection.

An optimal system exists on the edge of ‘chaos’; it is here where its ability to choose alternative futures is optimised ...

Understanding Complex Adaptive Systems In The Context Of Counter-Nation Networks

So how does one defeat a complex adaptive system? How does it have an impact on a nation’s ability to achieve a victory over a counter-nation network? Can a counternation network be permanently defeated? Or can one only learn to cope with it?

The first step in developing an approach to defeat a complex adaptive system such as a counter-nation network is to understand its traits and the behavioural elements of its constituent components in order to detect patterns that will form the base logic of an attack and defeat mechanism. Typical of these systems are the following traits: grouping, rule sets, network flow and competition.

Grouping

As elements of the complex adaptive system operate in parallel, their pattern of learning and behaviour invariably begin to generate similarities that will eventually form together for a specificity, whether it is functional, temporal or physical. These elements become ‘grouped’ and, therefore, become more easily recognisable within the system.

In the context of a ‘counter-nation network’ there are many examples of this ‘grouping’ phenomenon within a complex adaptive system. The Taliban, Terik-e-Taliban, the Haqqani Network, al-Qaeda, al-Qaeda (in the) Islamic Maghreb, and al-Qaeda (on the) Arabian Peninsula, all exhibit common patterns and are therefore ‘grouped’. As networks they share interdependencies such as lethal aid, technology transfer, ideological guidelines and common adversaries.

Rule Sets

‘Rule sets’ essentially define the behavioural limits that determine the pattern of the group. They set ‘benchmarks’ and limits on how groups apply themselves within their complex adaptive system. In the contemporary sense, rule sets are seen in many forms across counter-nation networks. Some of these rule sets include the limitations placed on targeting fellow Muslims by Islamic jihadists, the notion of ‘honour’ within customary and tribal systems that often define the rule set of their dominant narrative, and even the application of rules of engagement and laws of armed conflict by belligerent states within a declared conflict. The annual edicts of Mullah Omar to his followers, setting limits on targeting and civilian harassment is another example of the rule set that defines a network, in this case, the Taliban. Once rule sets are understood, then the complex adaptive system can in part be defined by its limitations and constraints.

Network Flow

All effective groups within a complex adaptive system possess the qualities and abilities to sense feedback and develop rapid ‘learning loops’. This flow of adaptation, learning and emergence is the essential energy required to maintain the homeostasis of the system. Without a consistent network flow, the system loses its learning loop and loses positive control over its adaptation and structure.

All effective groups within a complex adaptive system possess the qualities and abilities to sense feedback and develop rapid ‘learning loops’.

Network flow within a counter-nation network includes ideology, the production of an ‘own’ narrative (manifested through propaganda and other such materials), the organisation of a flattened leadership structure and multi-disciplined communications mechanisms, as well as the use of agents and operatives to inform the organisation of emergence and variance both inside and outside the network (this is an active, sensing, learning loop). The ‘Comintern’—the international communist movement that existed as a global communist network outside a single nation-state throughout the Cold War—is one example of a counter-nation network’s network flow. Its network fed directly into all communist systems, effectively enabling communist governments to interact and adapt as the global environment changed.

Competition

Competition, in a pure Darwinian sense, is an essential element of a complex adaptive system. This type of competition generally can be classed into two forms: constructive and destructive. Constructive competition is essentially an efficiency dividend. Through rapid evolution (encapsulated via the principles of a complex adaptive system as previously defined), the system becomes more efficient and increasingly effective at achieving its adaptation and goals. Destructive competition is where a system, denied an effective network flow, replicates the wrong adaptation traits, increasing its rate of entropy (more on this later) and descends over the edge of efficiency into irreversible chaos.

Within counter-nation networks, an example of constructive competition includes the efficiency of people trafficking networks’ ability to react to changes in border protection laws and systems that grant them the capacity to continue their movement of people. In essence, the people smuggling model constructively competes against border protection laws.

An example of destructive competition is the defeat of the Tamil Tigers by the Sri Lankan government when, as a result of a loss of network flow, the leadership falsely believed that their military capability had evolved to a point of supremacy. The subsequent Tamil attempt to bring their campaign to a final attritional strategic battle (phase three of Mao Tse-Tung’s people’s popular warfare model), in near total ignorance of the strategic overmatch that the Sri Lankan government possessed in terms of military hardware resulted in their ultimate destructive defeat.

Complexity-Based Targeting (How To Attack And Defeat A System)

The first step in attacking and defeating a complex, adaptive, counter-nation system is to review the principles and traits as previously described and then proceed to ‘map’ the network. Figure 1 maps a counter-nation network: in this instance, a narcotics cartel and the Taliban have formed together to facilitate a mutually-beneficial transactional outcome—opium provided by the Taliban to a Mexican cartel, in exchange for finance which in turn directly funds the Taliban lethal aid program (including the IED network) throughout central Asia.

The first step in attacking and defeating a complex, adaptive, counter-nation system is to review the principles and traits ...

Figure 1 maps the terrorism / narcotics network according to the traits evident as a complex adaptive system. At a macro-level, this analysis defines the narrative of the network, its aims, objectives and network linkages. It also gives insights into the ‘system within a system’, which in this case identifies the Taliban and the

|

Trait |

Terrorism/Narcotics Network |

Mechanism |

|

Grouping |

Taliban/Global Criminal Patronage Networks (Mexican drug cartels in AFG) cooperate in narcotics production and facilitation |

Similar elements of the system join together for a specific function |

|

Rule Sets |

Activities limited to transactional relationship, opium for money, ideology transfer completely outside the established rule set |

Such sets determine the behaviour of groups |

|

Network Flow |

Taliban: Support the facilitation of narcotics production in order to generate facilitation of lethal aid and external knowledge transfer—previously ideologically opposed; however, their network flow has informed their decision-making and they have adjusted accordingly Mexican drug cartel: persistent pressure on traditional areas in South America has informed their network flow, which has adapted their system to adopt a more global perspective |

Groups move throughout the system and are subject to feedback and interaction |

|

Competition |

Constructive: Taliban and Mexican cartel gain a monopoly on narcotics production in order to deny competition from external agents, as well as improve their efficiencies by broadening their network Destructive: Mexican cartel influence strays into Taliban ideological domain resulting in irreconcilable conflict and divergence |

Groups compete with each other as they interact. Competition can be either constructive or destructive |

Figure 1. Terrorism / Narcotics Network

Mexican cartels as two normally remote systems that, through common rule sets, network flow and competition, display true emergence by re-framing themselves as a terrorism/narcotics network.

By gaining an understanding of the traits of a counter-nation network such as this, the attacking adversary (in this instance, ISAF, INTERPOL, the Afghanistan government) can, as a result of mapping the network, begin to understand it. Notwithstanding this, mapping must be an iterative process, constantly renewed and refined as the network changes. This also acknowledges the previously mentioned principles of a complex adaptive network that thereby necessitates a need for a ‘near-constant’ review of its principles and traits.

An effective mapping process can then provide the basis for a more detailed network review, and the construction of a complex network targeting methodology. Emphasis can be further applied on the inter-relationships that exist between the network’s traits and its networks—this survey can occur with an up/down and left/right perspective in order to attain greater fidelity on the network. Targets (nodes) begin to appear, as well as networks (modes) that form the inter-dependencies across the entire system. Figure 2 illustrates this point using the previous Taliban/Mexican cartel network as a focal point of analysis.

An effective mapping process can then provide the basis for a more detailed network review ...

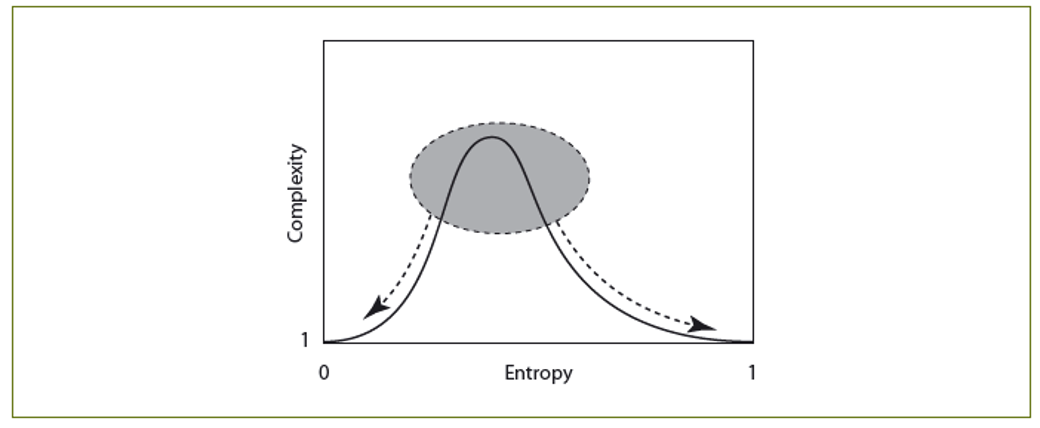

Once the network targeting priorities become clear, the aim of the network adversary should be now to attempt to inject a non-linear complexity into the network in order to induce chaos and ‘entrophy’ the network, cascading it to a point of termination and ultimate systemic destruction.

Network-based targeting offers a different perspective on the target system or systems by focusing on the interrelationship of elements within the larger system. One devotes particular attention to those properties and mechanisms that account for coherent behaviour in the system. Once this is understood, then the introduction of a successful non-linearity into the system (e.g. counter-narcotics law enforcement, international cooperation, counterinsurgent strategies to defeat the Taliban, improved border control, etc) can be applied with maximum effect.

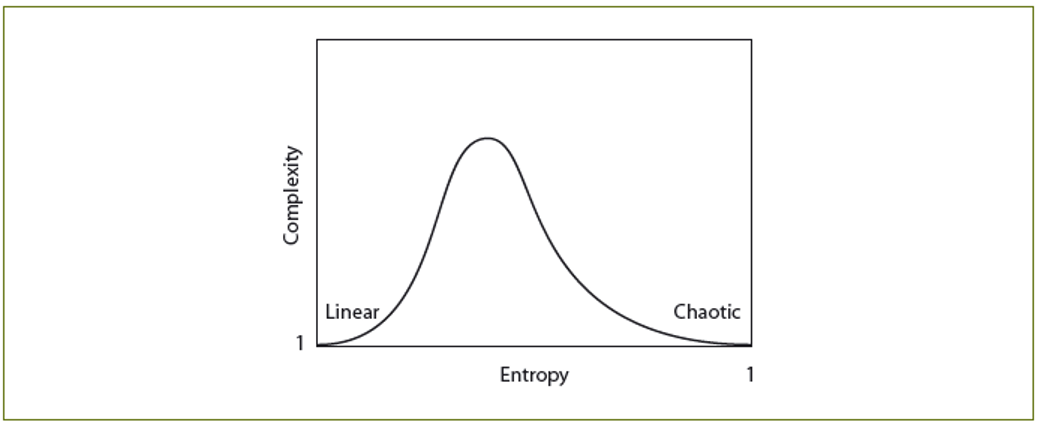

Two points of concentration when looking to create non-linearity underpin successful network based targeting: complexity and entropy.5 Complexity is a measure of the degree to which a system contains large numbers of interacting entities with coherent behaviour. Complexity can be effectively measured from a value of zero to some maximum number. This effectively informs the adversary of the amount of complexity that exists in the network and indicates the level of probable counter-network actions required. Entropy, on the other hand, is a measure of the amount of work lost in a system due to destructive forces such as friction or interference. Knowledge of the type of friction and interference is the focal point of the application of a successful counter-network targeting strategy. It is designed ultimately to induce such entrophy into the network that it ceases to properly function and is rendered a completely chaotic system, having lost all control. This sets in chain the seeds of the network’s own self-destruction. Irregular tactics such as counterinsurgency operations, psychological operations and targeted assistance are especially effective at inducing entrophy into a system.

|

Grouping |

Rule Sets |

Networks and Flows |

Competition (Constructive/Destructive) |

|

Taliban |

Ideology |

Commonalities of beneficial interest |

Price/transactional benefit dividend—Constructive |

|

Mexican cartel |

Approach patterns |

Chain of custody of narcotics, finance and lethal aid |

Divergence as a result of a change in the transactional nature of the relationship—Destructive |

|

Opium producers |

Agreed transactional processes |

Global reach |

Elimination of common enemies through joint capabilities (eg. Taliban conduct operations against rival narcotics network despite them not being a declared enemy IAW their jihadist principles)—Destructive |

|

External/internal narcotics/ lethal aid movement facilitators |

Access and control over broader societal issues |

IED and narcotic production skills transfer mechanisms |

Mexican cartel forms an alliance with a non-Pashtu group (Tajik, Hazaran)—Destructive |

|

Money launderers/international illegal financial systems |

Restrictions on access beyond narcotics network |

Control of street value of opium to maintain margins |

Effective generation of a narcotic supply chain that guarantees supply and facilitation of both opium and lethal aid to both parties—Constructive |

|

Lethal aid networks—IED manufacturers |

Undermine common enemies |

Use of corruption to render legal system non-effective |

Taliban allow import of greater technology to increase rates of production—Constructive |

|

Technology transfer facilitators |

Free passage |

Access to distributors |

Mexican cartels broaden operations to include IED production—Constructive |

|

Warehouses |

Access to leadership |

Quality controllers |

Taliban use cartels to attack Western interests—Constructive |

Figure 2. Complex network based targeting - Terrorism / Narcotics Network

Figure 3. Most complex adaptive systems

Figure 4. Driving a system into chaos

In the case of the Taliban/Mexican cartel network, an effective application of a counter-network attack can be derived by understanding and reviewing the principles and traits that form the network, and then by applying a targeting methodology that seeks to understand complexity and induce entropy. In this instance the attack and defeat mechanism would:

- Understand complexity by successfully identifying the different coherent groups in the system, including their contributions to the proper functioning of the entire network;

- Understand complexity by discovering the methods by which each group identifies and, therefore interacts with, other parts of the network;

- Define and analyse the basic rule set by which the system functions;

- Examine the direction, rate and alternative paths of network flows in addition to physical network components, information flows, knowledge flows, people flows, etc;

- Induce entropy by determining non-linearities such as choke points, failure thresholds and second order effects; and

- Induce entropy by determining methods for creating non-linearities internal to the network, pushing it into chaos and ultimate self-destruction.

Conclusion

Historically, targeting methodologies has reflected a mechanistic, linear, industrial-age approach, but complexity-based targeting uses a more holistic, systems-based approach. Importantly, it identifies each element and its functionality within a system. Complexity-based targeting unifies all methods of attack. It provides more useful, systemic knowledge of a target set and uses that knowledge to induce chaos and destruction through the introduction of non-linearities by transforming controlled behaviour into out-of-control chaos and confusion.

... complexity-based targeting uses a more holistic, systems-based approach. Importantly, it identifies each element and its functionality within a system.

How to cope with ‘counter-nation networks’—that is, those complex adaptive systems within the global system that threaten national sovereignty—is a difficult question to ponder, least of all answer. One thing is certain, however: the discovery of the inter-connectedness within these complex adaptive systems and their supporting networks requires a thorough understanding of the principles and traits that underpin these adaptive networks and their complex systems. In the case of terrorism, transnational crime, people-smuggling and drug smuggling, any application of a successful strategy must be underpinned by a sound analysis of the target as well as through the use of a systemic approach in designing an effective attack and defeat mechanism. Gone are the days of attritional operational design; a systems approach is now a fundamental tenet of all successful military strategy.

About the Author

Lieutenant Colonel Ian Langford is a graduate of the Royal Military College, Duntroon, the USMC Command and Staff College, the USMC School of Advanced Warfighting, Southern Cross University and Deakin University. He has deployed as part of several ADF and coalition operations throughout his career to various countries. He has commanded at the platoon, company, regimental (acting), and task group level.

Endnotes

1 ‘Quotes of Albert Einstein’, Brainyquote.com <http://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/authors/a/albert_einstein.html> accessed 29 June 2012.

2 Carl von Clausewitz, On War [Vom Krieg] (Indexed ed), edited and translated by Michael Howard and Peter Paret (eds), Princeton University Press, New Jersey, (1984) [1832], pp. 1–234.

3 Ben Saul, ‘The Dangers of the United Nations’ “New Security Agenda”: “Human Security” in the Asia-Pacific Region’, Asian Journal of Comparative Law, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2 October 2008, pp. 1–35.

4 R Freniere, J Dickmann and J Cares, ‘Complexity Based Targeting: New Sciences Provide Effects’, Air & Space Power Journal, Spring 2003, pp. 12–18.

5 Ibid.