Abstract

Adaptive Campaigning— Future Land Operating Concept describes the Australian land force’s response to the challenges of future warfare. It discusses the need for Army to perform successfully over various lines of operation and to maintain an adaptive approach in order to achieve its objectives. However, the novel nature of this approach poses some challenges in its practical implementation. A visualisation technique known as influence diagrams is employed to examine adaptive campaigning and help support its further development as a concept.

Although conflicts have always incorporated both conventional and unconventional aspects, the focus of doctrine development and materiel acquisition appears to have been more on the side of conventional warfare. More recently however, military doctrine has started to explicitly incorporate the unconventional aspects. This is essential as complex asymmetric conflicts cannot be won by conventional approaches alone.

Adaptive Campaigning—Future Land Operating Concept (Adaptive Campaigning) outlines the Australian land force’s response to the conflict environment as part of the military contribution to a whole-of-government (WoG) approach to resolving conflicts, whether they are conventional or unconventional. It was first published in 20071 with a revised version in 20092. There have been a number of iterations of the main document as well as sub-concepts, some formally endorsed and some remaining only in draft format. Adaptive Campaigning is dynamic and the last endorsed version is a living document. It will change over time as a result of changes in the environment, experience on the ground and lessons learnt.

In this paper we employ a visualisation technique called influence diagrams (IDs) to extract the key components of the concept in order to assist the concept developers to improve the concept by filling in some holes in its next iteration. However, the ID is not limited solely to this utility; it can also assist people who will implement the concept. Our focus has been the use of IDs of adaptive campaigning (AC IDs) as a concept tool, an implementation tool and a teaching tool.

This article first provides a short summary of Adaptive Campaigning, highlighting the novel nature of the concept and the involvement of many actors. This is followed by a section on visualisation techniques, particularly IDs, which can simplify the understanding of the concepts described in Adaptive Campaigning and make it more user-friendly. Examples of how AC IDs have been developed in order to support implementation and training are summarised. The paper also reveals how IDs are well suited to examine the adaptive campaigning concept. This then leads into the development of another set of AC IDs to support concept developers as they work on keeping the concept current and complete.

Adaptive Campaigning

Adaptive Campaigning outlines the Australian land force’s response to the conflict environment as part of the military contribution to a whole-of-government (WoG) approach to resolving conflicts.3 Adaptive campaigning is not a counterinsurgency concept but a concept which incorporates both conventional and non-traditional military aspects in a complex environment. It describes the reasons for the Army to adopt an adaptive approach to future military operations dependent on continuously evolving complexity and operational uncertainty.4 The purpose of adaptive campaigning as a warfighting concept is to set out how best the land force can influence and shape perceptions, allegiances and actions of a target population to allow peaceful political discourse and a return to normality. Given the complexities of the environment the key to the land force’s success is expected to be its ability to effectively orchestrate effort across the five lines of operation (LOOs). These, with their Australian Army (2009)5 descriptions, are:

- Joint Land Combat (JLC)—actions to secure the environment and remove organised resistance, and set conditions for the other LOOs;

- Population Protection (PP)—actions to provide protection and security to threatened populations in order to set the conditions for the re-establishment of law and order;

- Information Actions (IA)—actions that inform and shape the perceptions, attitudes, behaviour and understanding of target population groups;

- Population Support (PS)—actions to establish/restore or temporarily replace the necessary essential services in affected communities; and

- Indigenous Capacity Building (ICB)—actions to nurture the establishment of civilian governance, which may include local and central government, security, police, legal, financial and administrative systems.

... how best the land force can influence and shape perceptions, allegiances and actions of a target population to allow peaceful political discourse and a return to normality.

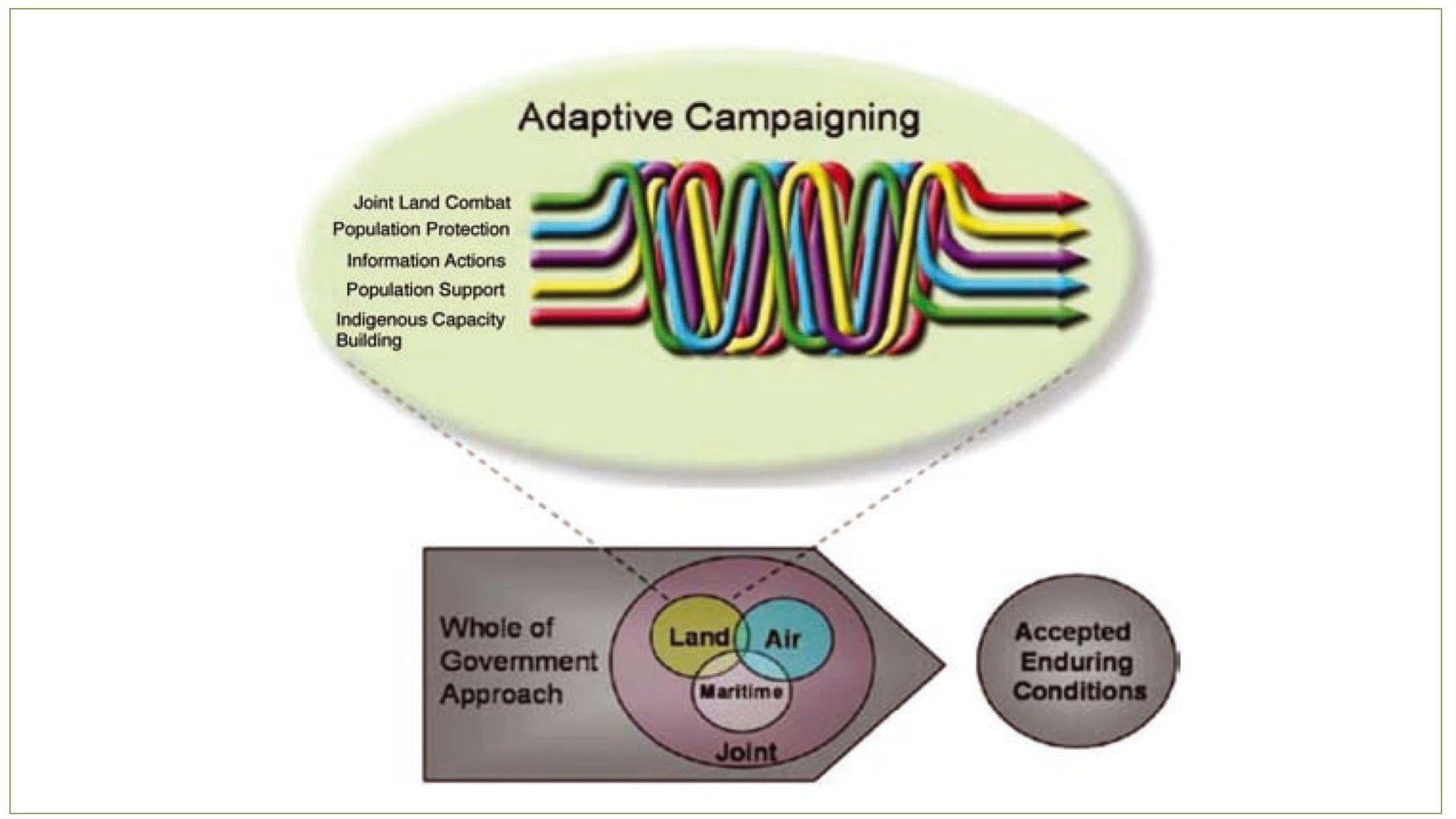

Adaptive Campaigning emphasises the interdependence of the LOOs and their ability to reinforce each other. Hence, the ability of the land force to effectively orchestrate effort across all five lines is considered as a key to successfully achieving its mission. Moreover, operational uncertainty early in a campaign may most likely require the land force to take also the leading role in non-warfighting activities (Figure 1).

For the Australian Army to operate over the five LOOs with greatest effectiveness in order to achieve mission success in an ever-changing asymmetric complex environment, it needs to be able to adapt to emerging changes during the campaign. This requires the ability to quickly shift the main efforts and focus within individual LOOs as well as across LOOs. The capabilities required to operate effectively over the five LOOs include operational flexibility, responsiveness, agility and resilience.6

Operational flexibility is the ability of Army to remain effective across a various range of tasks, situations and conditions and the ability to have the means to change the main areas of focus when needed. Operational responsiveness is the ability to rapidly change effort. This is essential for responding to emerging threats in an everchanging environment but is also the key to exploiting emerging opportunities that present themselves as a campaign unfolds. Operational agility involves knowing when to, and being able to, shift strategy, by dynamically managing the balance and weight of effort across the LOOs. Operational resilience can be defined as the ability to be resistant to shock. It is the capacity to sustain loss, damage and setbacks yet still maintain a level of capability above a given threshold.8 These four capabilities along with robustness, the insensitivity to enemy actions, are essential for having the capability to operate over the five LOOs and to succeed in complex environment campaigns both conventional and asymmetric.

Figure 1. Adaptive campaigning within the army conceptual framework.7

Since the introduction of Adaptive Campaigning in 2007, with a revised version in 2009, there have been journal publications addressing various aspects of this concept, ranging from specific fundamental components which make up the concept to how various aspects of the Army may implement the concept in operations. This suggests that the concept is becoming familiar to more officers and soldiers and that its implementation across the board is progressing. Some examples of discussions relating to adaptive campaigning include:

- describing the differences (or similarities according to some) between the observe-orient-decide-act (OODA) loop and the act-sense-decide-adapt (ASDA) adaption cycle, also known as the adaptation cycle9;

- why ASDA needs to be conducted at the minor tactical level and not just the strategic level (this requires empowering junior leaders to be able to apply the adaption cycle)10;

- highlighting the importance of adaptive campaigning to Army doctrine and developing officers11;

- the leading role chaplains could play in welfare warfighting across the five LOOs and how they would operate to support each LOO12; and

- the need for health personnel to take additional responsibilities in order to achieve the five LOOs and how health support could fit into each of the LOOS13.

... the concept is becoming familiar to more officers and soldiers and that its implementation across the board is progressing.

Influence Diagrams

Many techniques can be used to unravel complex systems. These often involve using diagrams and pictures to help the human mind grasp and better understand relationships, connections and effects. They are judgement-based and represent one potential interpretation of the problem. Depending on the nature of the problem, some techniques will be more beneficial than others. Some commonly-used techniques include mind maps, impact wheels, ‘why’ diagrams and influence diagrams.14 These techniques help illustrate, visualise and analyse problems and reveal key gaps in knowledge about the problem.15

The novel nature of adaptive campaigning makes it suitable for the application of visualisation techniques. IDs help identify influences one action or event has over other actions and events and can also identify feedback loops. They are particularly useful when analysing complex situations because they allow a clearer understanding of the connections between the components. Some IDs may include time delays. When constructing an ID, all influences between actions and events must include a positive or negative sign to highlight the nature of the influence. Once a feedback loop is formed, the presence of the influence signs allows loops to be identified as either reinforcing loops or balancing loops. An additional property of IDs is that the same situation can be examined at different levels, allowing greater understanding of the situation and also so the most suitable diagram can be used to communicate the findings to a desired audience. This means that an ID can be developed specifically for a particular audience while a different ID of the same situation can be used for a different audience. Finally, IDs can also be used as the basis upon which system dynamics models are developed.16

The application of IDs to military problems is not new. A few select examples of previous work include:

- the development of a generalised counterinsurgency ID to understand the feedback loops and how changes in approaches might create reinforcing effects17;

- how IDs can be used to support the development of military experiments18;

- their application relating to the Colombian civil war to understand the impact of greed and past grievances on the warring factions19; and

- the use of IDs to model counterinsurgency in Iraq (Fallujah) and Afghanistan20 which have been described as ‘hairball’ diagrams and discussed extensively in the media.

Other examples of previous military-related applications of IDs are also available in the literature.21

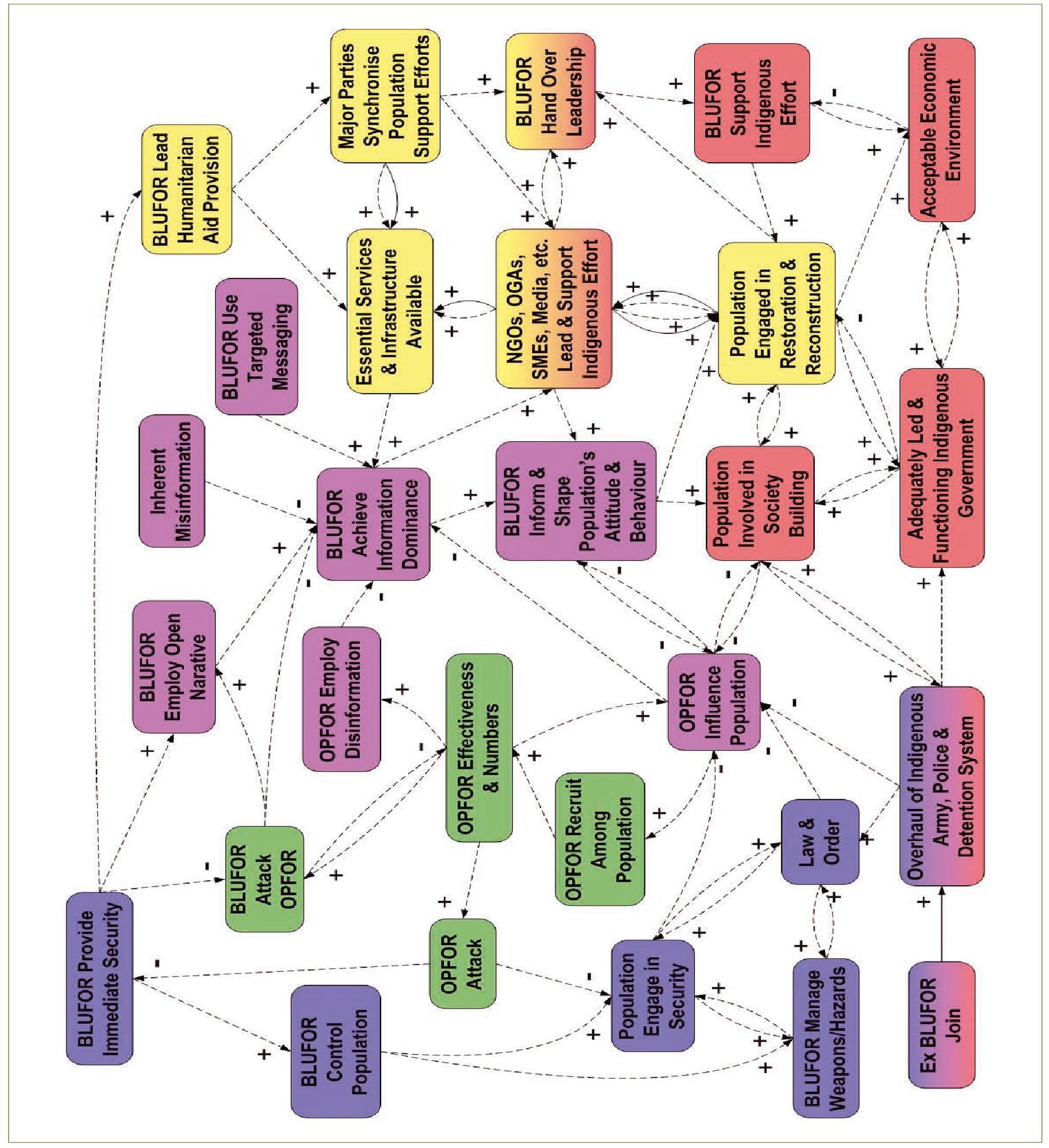

An ID of the adaptive campaigning concept also was developed.22 The diagram was based on Adaptive Campaigning23 and its sub-concepts24 with the addition of tasks and activities supporting them. Figure 2 reproduces this diagram.

The diagram clearly reveals the influences between the LOOs, highlighting the need to consider all five lines and not focus solely on JLC and expect this to be sufficient. This philosophy is already being implemented by the ADF, with one example being the Australian Reconstruction Task Force in the Uruzgan Province of Afghanistan. They have for several years been engaged in supporting local population groups by rebuilding facilities such as mosques and local gathering halls while also teaching locals trade skills through trade training schools.

This AC ID was the first step in revealing the potential applicability of this visualisation technique to support the understanding and implementation of this concept.

The first benefit of developing an ID of the concept is that the graphic nature of the diagram clearly supports the philosophy which underpins the concept to anybody who is exposed to it for the first time. The ID clearly identifies the interdependencies of the LOOs and therefore the need to conduct operations involving all five LOOs. The cross-LOO influences along with the pathways of influence (connections of several actions and events) and loops, support the assertion that the lines cannot be considered-independently in sequence but should be considered holistically with emphasis on particular LOOs changing as the environmental conditions of the campaign evolve. Adaptive campaigning has been further explored by mapping various operational tactics employed by US forces in Baghdad25 on top of the essential tasks and activities AC ID.26 It revealed that when actions were spread across the LOOs the outcome was better than when actions were focused on a particular LOO such as population protection. In this example, there was a strong correlation between the actions and outcomes in the real world and what would have been expected by interpreting this AC ID and developing a campaign plan. This supports that the AC ID can be used to assist in the development of future campaign plans to ensure actions are spread across the spectrum of LOOs.

... when actions were spread across the LOOs the outcome was better than when actions were focused on a particular LOO such as population protection.

Utilising essential tasks and activities AC ID during an operation can also be of great benefit. One of the main areas of application is in measuring the success of a campaign. With conventional warfare, measures can be based around kill ratios and ground taken, but in a complex environment these measures may not be so informative. However the sub-concepts and enablers present in such an AC ID may in fact be better nodes to probe and measure success and campaign progress. Gauging effectiveness in one area may also be used to prepare for actions in other areas due to the further-reaching and time-delayed influences.

Figure 2. Essential tasks and activities AC ID.27 Here and in all other diagrams a full arrow stands for physical movement of people, a dashed arrow describes information flow or influence exerted and the different colours correspond to the sub-concepts of adaptive campaigning.

Explicitly identifying the network of influence also means this ID could be used to support the adaptability of the land force. The identification of many pathways increases potential flexibility as there are several different action pathways which can be taken to achieve the desired outcomes. It increases responsiveness by allowing rapid changes to be made when effectiveness with one approach is on the decline. Utilising more than one pathway to achieve the same desired outcome means the approach has greater resilience and robustness as the influence will continue through one pathway if an attack and consequent loss of influence occurs in another pathway. Highlighting all the influences (even though at certain times not all regions will be covered by the land force and coalition partners) supports identifying potential areas where the enemy may try to operate. This at least allows sensors to be put in place to monitor activity in these areas.

... there are several different action pathways which can be taken to achieve the desired outcomes.

In addition to operations planning and analysis, IDs can also be used for predeployment training; either for a specific operation or for the general training of officers and soldiers. IDs can also be used during experimentation; experimental planning, computer wargaming, seminar wargaming and for adjudication purposes during these activities.

More recently, the AC ID in Figure 2 has been used to demonstrate how this visualisation technique could help in communicating and sharing understanding with coalition partners, other government agencies, and indigenous and international non-government agencies.28 Cross examination of IDs can support understanding of other coalition approaches for the same environment. It can also support the synchronising of approaches, or at least combining them into the same diagram to understand where the differences are.

In large operations with coalition partners, it may be more effective to divide and focus on particular roles rather than each partner trying to cover the entire spectrum of operational activities. A shared ID could support this distribution of tasks between the coalition and also civil-military cooperation partners. The influences between activities being undertaken by different groups can help coalition partners understand how their actions in one area can have an influence on others working on different activities. Identifying these interfaces between group activities can improve communication between partners.

One of the main benefits of using influence diagrams as a communications tool is that the technique is user-friendly and can be used at multiple levels depending on the intended audience.29

Application to Concept Development

The remainder of this paper will explore whether IDs can be used first to understand the written concept as a whole, and second to work towards more comprehensive concepts in the future.

To consider this first aspect, an ID needs to be developed which considers only the concepts mentioned in the Adaptive Campaigning documents and the influences detailed in those documents. An ID was developed by the authors for each of the sub-concepts (JLC, PP, IA, PS and ICB) independently and then fused to form one ID which represents adaptive campaigning as a whole.

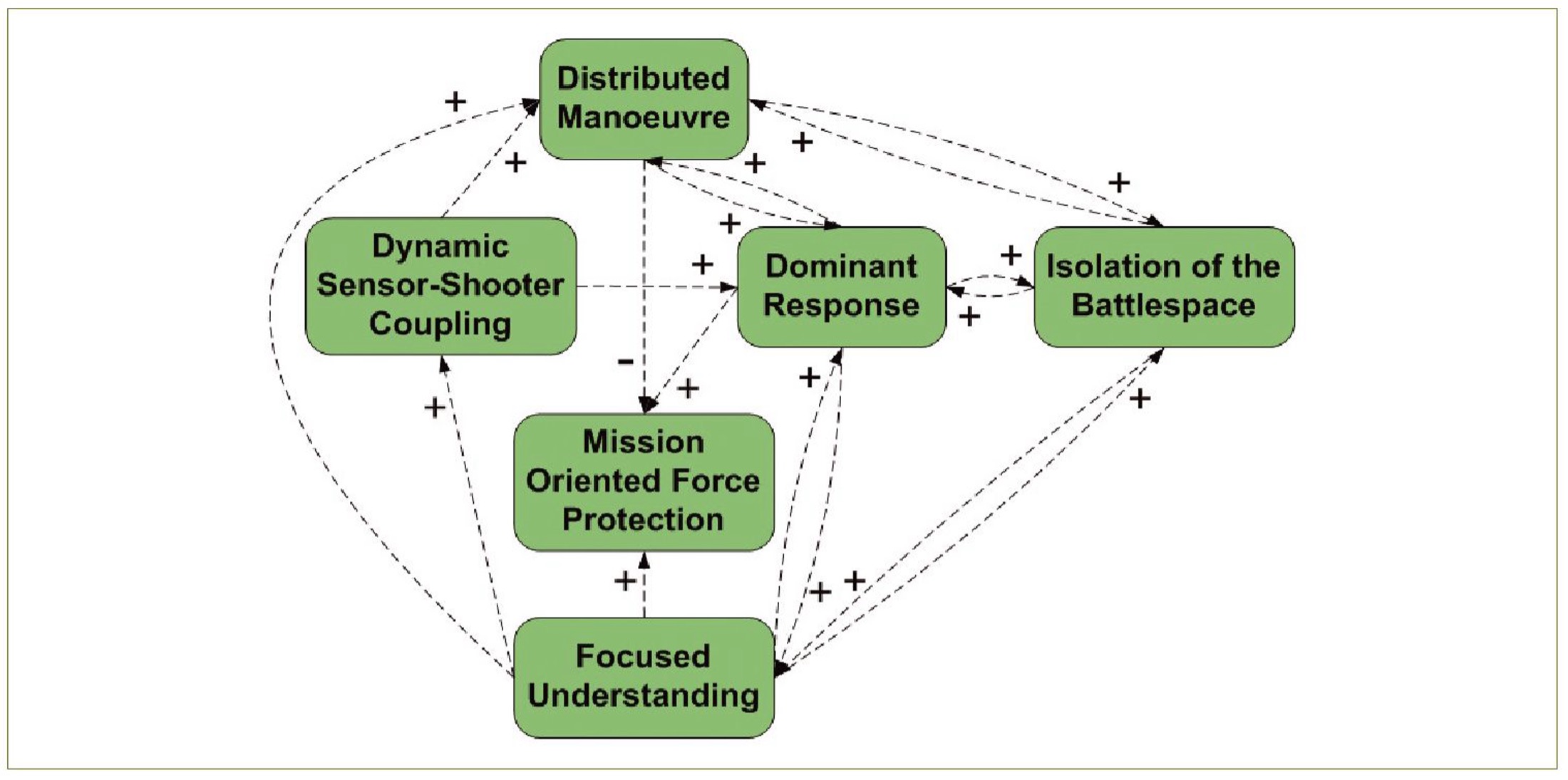

The JLC sub-concept paper30 describes the following concepts: dynamic sensorshooter coupling; distributed manoeuvre; dominant response; isolation of the battlespace; mission-oriented force protection, and focused understanding. The influences between these concepts as described in the document are represented in visual form in the ID for JLC in Figure 3. It is worth noting that distributed manoeuvre has a negative influence on mission-oriented force protection and this reflects the idea that as opposing force operates in a more and more distributed manner, force protection will become increasingly difficult. Obviously force protection can and will still be achieved, and this is recognised by the one-way influence as mission-oriented force protection does not negatively influence distributed manoeuvre.

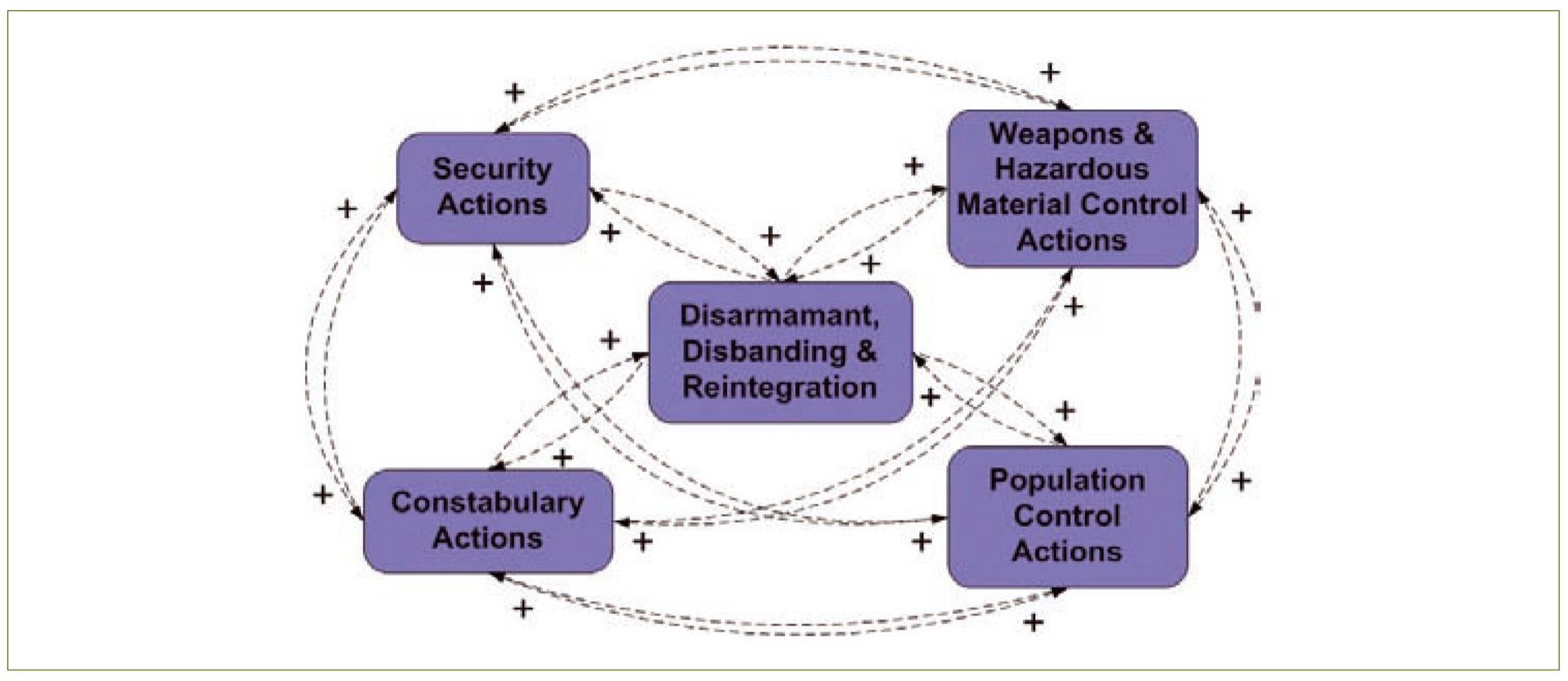

The PP sub-concept31 consists of security actions, population control actions, weapons and hazardous material control actions, and constabulary actions, with the central aim to achieve disarmament, disbanding and reintegration. The ID (Figure 4) reveals a set of several positively reinforcing feedback loops which features links between any two sub-concepts. That means any successful action undertaken will positively influence the other actions or sub-concepts which will eventually return with a positive influence on the original sub-concept.

... any successful action undertaken will positively influence the other actions or sub-concepts which will eventually return with a positive influence on the original sub-concept.

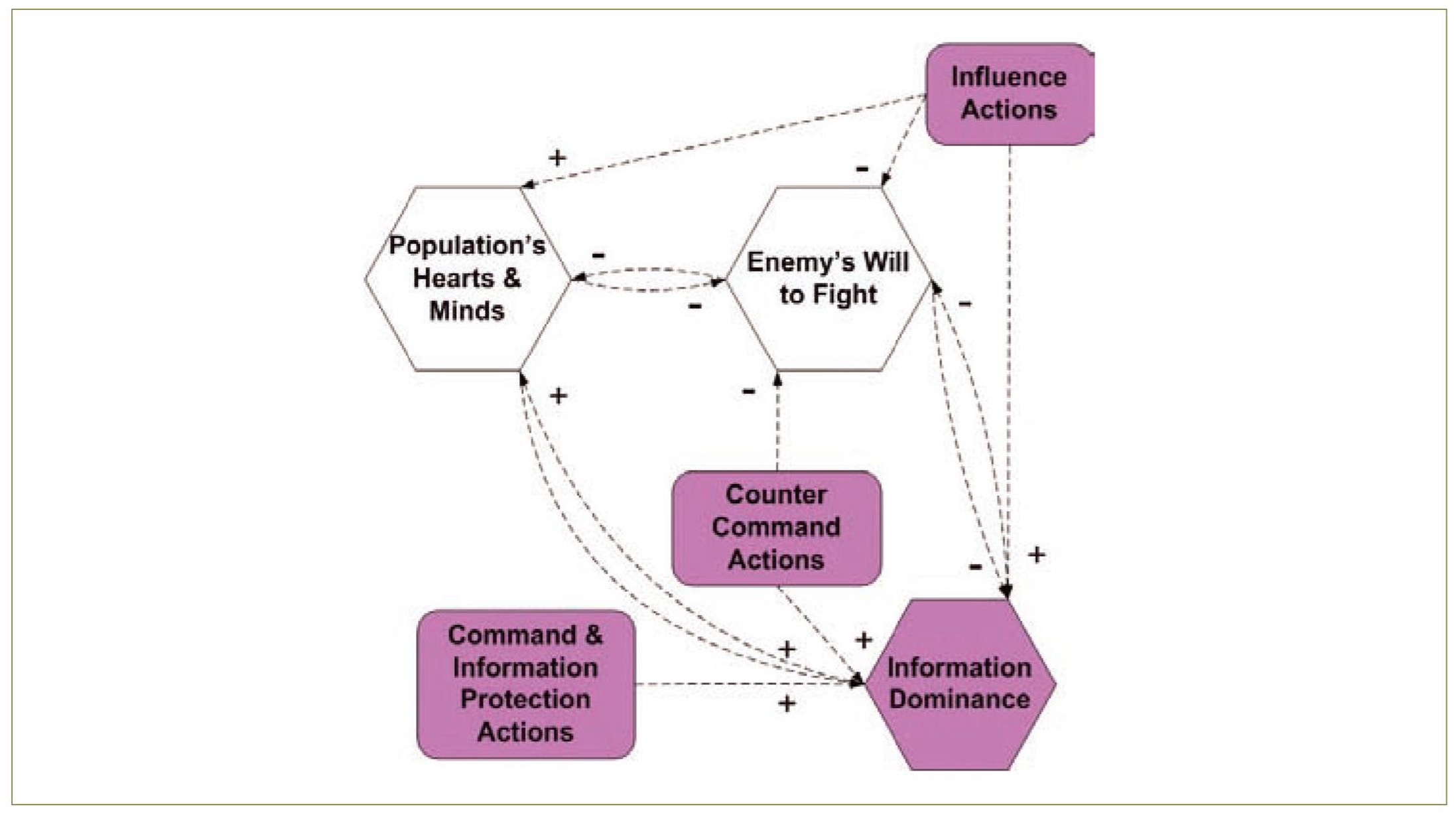

For the information actions (IA) LOO, in addition to the sub-concepts described in the documentation32, three additional sub-concepts have been included in the diagram as hexagons (Figure 5). These three sub-concepts are mentioned throughout Adaptive Campaigning but are not explicitly stated as sub-concepts for this LOO. Information dominance is seen as the key outcome that information actions is aimed towards maintaining/achieving through its actions. The other two, ‘enemy’s will to fight’ and ‘population’s hearts and minds’, although not explicitly discussed in the sub-concept have been included due to their key role. Their importance is further supported in Adaptive Campaigning, overseas doctrine and by other authors.33

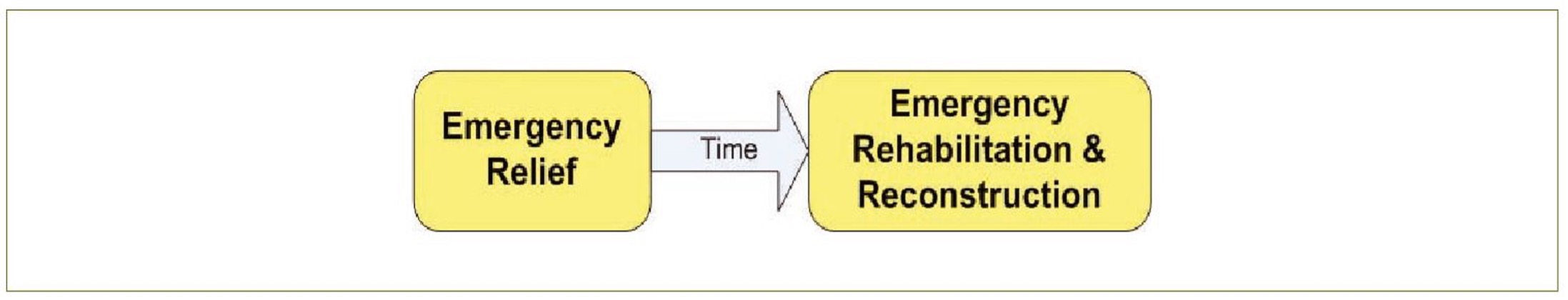

The diagram (Figure 6) for PS is technically not an ID. It is a chronological diagrammatic representation of where the initial action/sub-concept of emergency relief gives way to emergency rehabilitation and reconstruction over time as described in the sub-concept document for PS.34 This diagram is the only one that explicitly shows time delay.

Figure 3. Influence diagram of joint land combat sub-concepts.

Figure 4. Influence diagram of population protection sub-concepts.

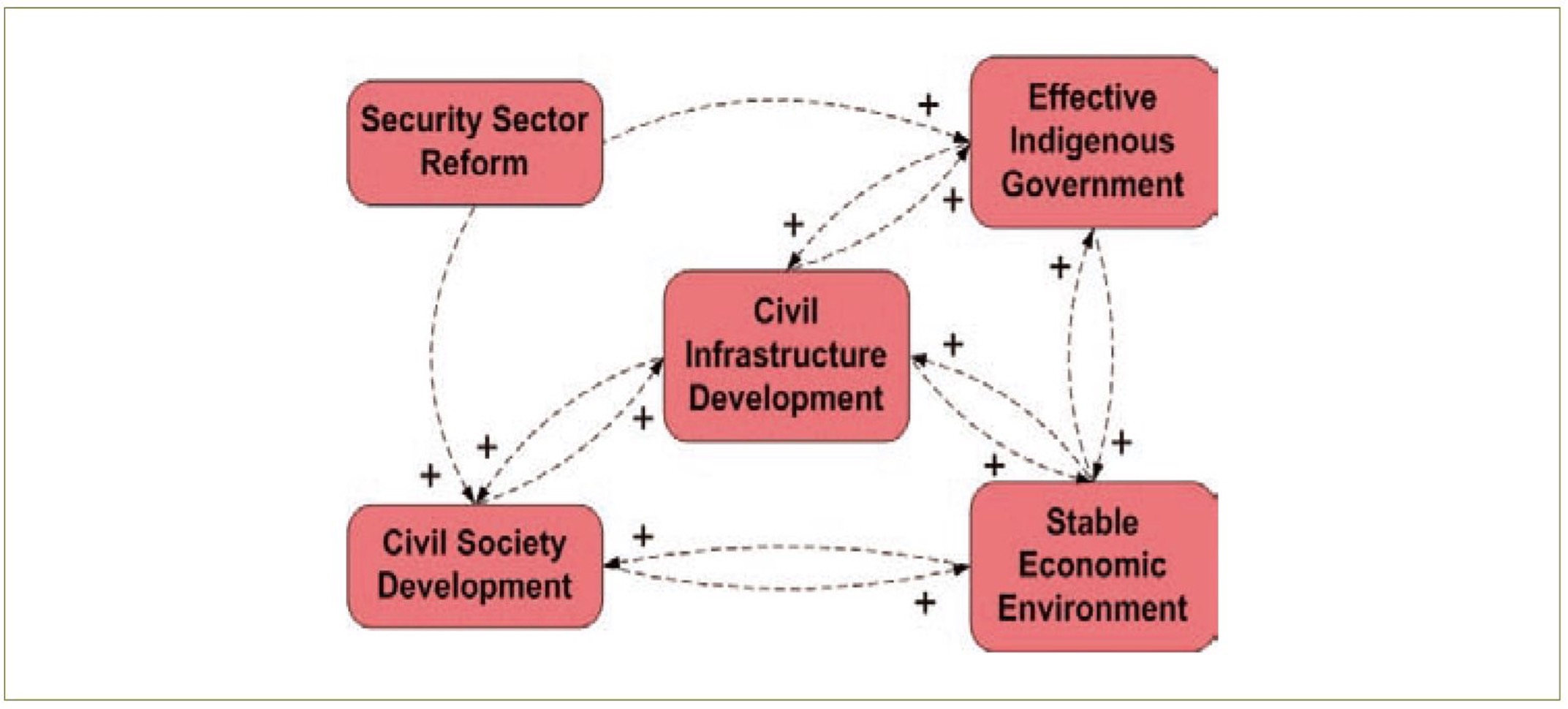

The influences documented within the ICB LOO35 are shown in Figure 7. The term ‘stable’ in stable economic environment refers to a level of economic activity which is satisfactory to the Australian Government and the context of the host nation and region. It is worth noting that in this diagram there are no actions which influence security sector reform according to the sub-concept document. However, security sector reform sets the conditions for effective indigenous government and civil society development.

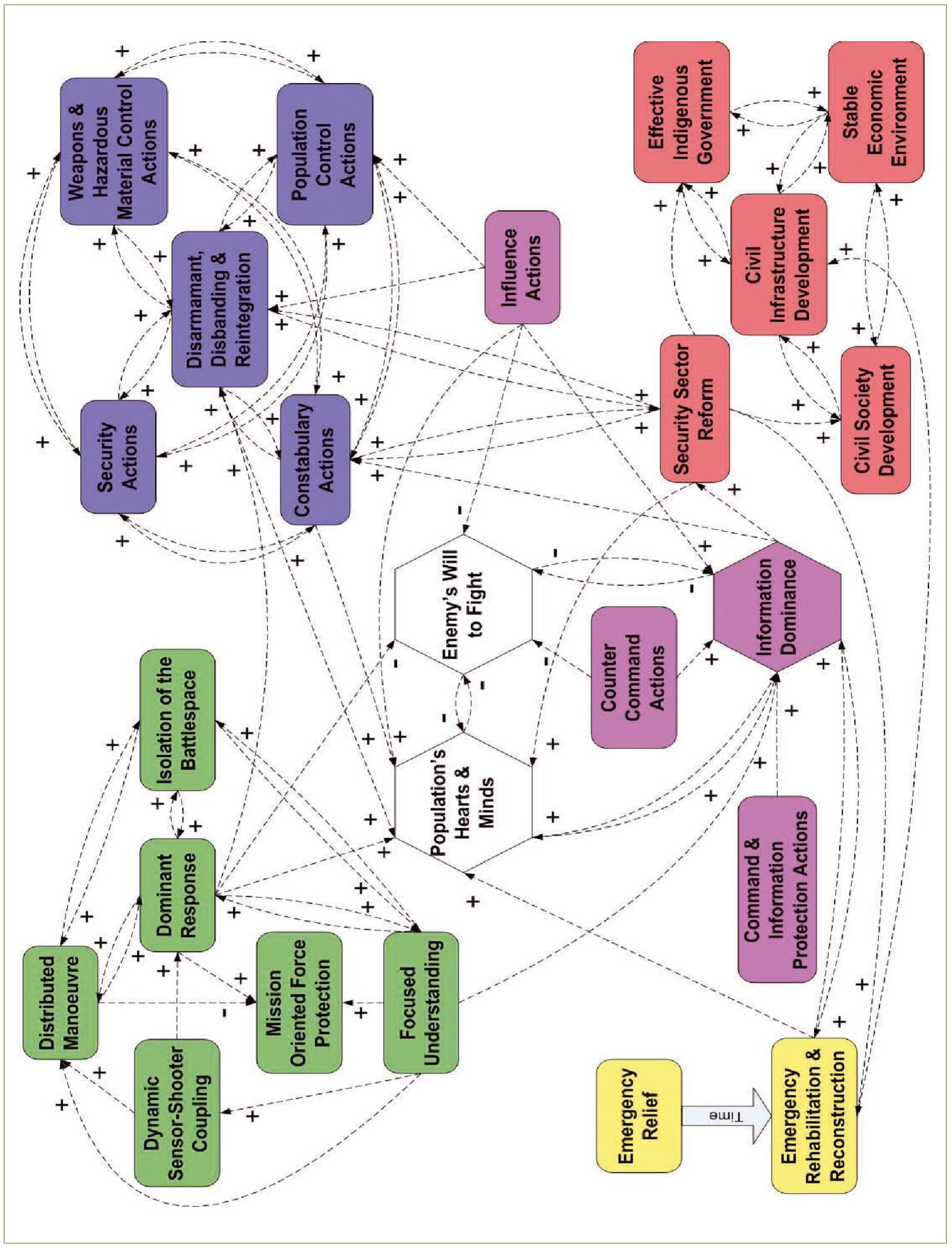

Adaptive Campaigning strongly advocates the essential need to conduct operations over all five LOOs as each line has the potential to influence the ability to conduct actions over other LOOs. Therefore, it is of interest to combine the IDs of the individual LOOs into one diagram to clearly identify the cross-LOOs influences. This was conducted by placing the five LOO IDs onto a single page and then linking components together where either direct influences were mentioned in the concept documents or were sufficiently well described enabling a possible influence to be identified. Only such explicitly considered cross-LOO influences are shown in the overall ID in Figure 8.

Figure 5. Influence diagram of information actions sub-concepts.

Figure 6. Influence diagram of population support sub-concepts.

Interpretation of the Sub-Concepts ID

From Figure 8 it can be seen that all of the influences identified are positive except for those relating to the enemy’s will to fight and between distributed manoeuvre and mission-oriented force protection. What this suggests is that during a campaign, if things are ‘going well’ they will continue to improve. For example (from the ID in Figure 8), if there is an improvement in security sector reform, this will lead to better results in shaping the population’s hearts and minds, which has a positive influence and therefore leads to greater information dominance and this in turn will improve security sector reform. Once this reinforcing loop is established, it will continue to cycle leading to ever increasing levels of security sector reform, information dominance and winning the population’s hearts and minds. However, what happens if the situation is not improving but declining? If information dominance is declining, according to this ID, this will lead to a reduction in security sector reform which has a negative impact on population’s hearts and minds (for a positive influence, more leads to more and less leads to less). This in turn reduces the information dominance and this damaging reinforcing cycle continues. The ramifications of having insufficient negative influences are that if things are not going so well, the situation will continue to spiral downward (negative influences are not ‘bad’, they are influences where more leads to less, and less leads to more. A theoretical example of a negative influence is where increasing security along a route reduces the likelihood of an improvised explosive device being emplaced on that route).

Figure 7. Influence diagram of indigenous capacity building sub-concepts.

Figure 8. Sub-concepts AC ID.

To break this downward spiral, a major change needs to be made. One option is to increase other actions (such as command and information protection actions) which have a positive influence on components of the reinforcing loop. If this positive influence on information dominance is significant and outweighs the reduction in information dominance from sliding, this may allow the loop to return to an improving reinforcement. An alternate solution is to activate entirely new reinforcing loops which also have an influence on the population’s hearts and minds. Having multiple actions influencing this component of the system may be sufficient to sway the situation back in favour of the land force and coalition partners. A third approach which could be taken is to initiate one or several balancing loops in order to break the downward feedback loop and bring the situation back to favour.

Balancing loops (which have an odd number of negative influences) tend to a particular level of equilibrium for a given environment. Over time, continuing actions (or even increasing actions) in a balancing loop will not improve (nor degrade) the situation. There may be some fluctuations but the nature of the balancing loop is to maintain a relatively constant cycle. Where balancing loops are of greatest importance is when a reinforcing loop is spiralling out of control. Activating a balancing loop which overlaps with the reinforcing loop can bring the level up to a neutral point of equilibrium. Once this level is reached, continuing actions in the balancing loop will have limited improvement, but it is at this stage that the balancing loop can be de-activated (re-enabling the reinforcing loop) to allow the upward reinforcement of the cycle. Such considerations may support the idea for a surge in operations and when it is required.

Where balancing loops are of greatest importance is when a reinforcing loop is spiralling out of control.

However, for this to be possible, the concept (and therefore the ID) should have sufficient negative influences to allow the decision maker a choice of potential tasks which could either be initiated or enhanced to activate the balancing loops. The ID in Figure 8 of the current concept clearly reveals that there are an insufficient number of negative influences to enable this. However, this may not necessarily be the case; these negative influences may in fact be implicitly present in the concept but because the ID was developed by joining sub-concepts where influences were explicitly mentioned in the documents, they were left out. As Adaptive Campaigning is the foundation document for the future operating environment, all these implicit influences should be brought to the surface and made explicit. It is essential to have all these influences explicit to enable future development and planning. Examination of the ID in Figure 2 which includes additional essential tasks and activities to those described in Adaptive Campaigning may be of some assistance in this process. If these influences were to be made explicit in the development of the next iterations of the concept, this would allow a more concise ID to be developed which could then be used to better support the implementation of the concept.

One of the core messages of Adaptive Campaigning is the need for the land force to orchestrate their efforts across the five LOOs36. Rather than consider each LOO in sequence during an operation, they should be considered as a group since Adaptive Campaigning also emphasises the interdependence of the LOOs and that they mutually reinforce each other. Conducting actions on one LOO will influence the ability to conduct actions on the other LOOs. Therefore, it is to be expected that there are many cross-LOO influences which describe how particular actions within one LOO influence various actions within the other LOOs. Examination of the ID in Figure 8 does not provide enough evidence of this as there is a rather low number of cross-LOO influences which were drawn out from the concept documents.

Is this a result of considering each LOO independently in close detail in the five sub-concept documents of Adaptive Campaigning and spending insufficient time linking the LOOs together? Possibly, but once again it may be that these cross-LOO influences are present implicitly within the concept documents but are simply not explicit. It may also be an artefact of the relatively new nature of this type of thinking resulting in some actual influences not yet being fully understood and articulated.

Whether the cross-LOO influences are implicitly present in the concept, or not articulated at all, the ID in Figure 8 may help in allowing the concept developers to explicitly state in future versions of the concept where (what and why) these cross-LOO influences are. Having the cross-LOO influences explicitly stated will support improved planning and implementation of the concept to current and future operations.

In this document we have utilised IDs to visualise diagrammatically the current version of Adaptive Campaigning and identify potential aspects which should be considered for future versions. However, the use of IDs is not limited to a post-analysis tool; it could also be used to support concept development in real time. This would involve the concept developers drawing the influences onto the ID as they develop the concept. Conducting these activities in parallel will improve the developers’ mental models of the system they are describing and should result in greater coverage and a more thorough concept. The IDs may also be included in the concept document itself to allow readers instant access to the visual mode of the concept and help achieve a common understanding. This will assist readers to develop their own consistent mental models of the concept and develop further IDs specific for the application they require.

... the use of IDs is not limited to a post-analysis tool; it could also be used to support concept development in real time.

Conclusions

Adaptive campaigning is a means for fighting human-centric warfare in the 21st century. Its foundation is the need for an adaptable Army to consider all five interdependent LOOs in order to achieve the desired end state. To identify potential gaps in the influences between LOOs, the sub-concepts of adaptive campaigning have been displayed individually in the form of IDs and aggregated to a common ID. These diagrams can then be used:

- as a tool to assist in better understanding the concept;

- to support the implementation of the concept; and

- to help develop or improve the next iteration of Adaptive Campaigning.

Previous papers applying AC IDs to a real world military operation provide a strong correlation between conducting operations over multiple LOOs and the end-state conditions. This suggests that the philosophy underpinning adaptive campaigning is well suited to the current operational environment.

The IDs show that the current iteration of adaptive campaigning contains a relatively low number of cross-LOO influences and also a low number of negative influences, both within and across LOOs. Many of these influences may not have been included in the documentation due to their implicit nature. The utilisation of IDs in the process of further concept development could assist in exploring more thoroughly the intra- and inter-LOO influences. An extension of this would be to develop related IDs for Royal Australian Navy, Royal Australian Air Force and Joint/coalition.

Endnotes

1 Australian Army, Adaptive Campaigning: The Land Force Response to Complex Warfighting, Future Land Warfare Branch, Army Headquarters, Canberra, ACT, 2007, accessed 29 June 2007, <http://intranet.defence.gov.au/armyweb/sites/DGFLW/docs/AC_print_versio…;.

2 Australian Army, Adaptive Campaigning 09: Army’s Future Land Operating Concept,

Head Modernisation and Strategic Planning—Army, Army Headquarters, Canberra, ACT, 2009, accessed 5 February 2010, <http://intranet.defence.gov.au/armyweb/sites/DFLWS/docs/Adaptive_Campai…;.

3 Ibid.

4 Anne-Marie Grisogono and Alex Ryan, ‘Operationalising Adaptive Campaigning’, Presentation to the 12th International Command and Control Research and Technology Symposium (ICCRTS): Adapting C2 to the 21st Century, Newport, RI, USA, June 2007; accessed 7 Jan 2009, <http://www.dodccrp.org/events/12th_ICCRTS/CD/html/papers/198.pdf>; and K J Gillespie, ‘The Adaptive Army Initiative’, Australian Army Journal, Vol. VI, No. 3, 2009, pp. 7–19.

5 Australian Army, Adaptive Campaigning 09, p. 28.

6 Ibid., p. 29.

7 Ibid., p. 30.

8 Ibid., p. 30.

9 Charles Dockery, ‘Adaptive Campaigning: One Marine’s Perspective’, Australian Army Journal, Vol. V, No. 3, 2008, pp. 107–118; Justin Kelly and Mike Brennan, ‘OODA Versus ASDA: Metaphors at War’, Australian Army Journal, Vol. VI, No. 3, 2009, pp. 39–51; Jason Thomas, ‘Adaptive Campaigning: Is it Adaptive Enough?’, Australian Army Journal, Vol. VII, No. 1, 2010, pp. 93–108; and Chris Field, ‘Adaptive Campaigning: Letter from Colonel Chris Field in Response to Lieutenant Colonel Jason Thomas’, Australian Army Journal, Vol. VII, No. 3, 2010, pp. 183–6.

10 David Ashley, ‘Adaptive Campaigning and the Need to Empower Our Junior Leaders to Deliver the “I’m An Australian Solder” Initiative: A Continuing Challenge for the Commander and the RSM’, Australian Army Journal, Vol. VI, No. 3, 2009, pp. 33–38.

11 Chris Smith, ‘Solving Twenty-First Century Problems with Cold War Metaphors: Reconciling the Army’s Future Land Operating Concept with Doctrine’, Australian Army Journal, Vol. VI, No. 3, 2009, pp. 91–105.

12 Chris Field, ‘Welfare Warfighters and Adaptive Campaigning’, Australian Army Journal, Vol. V, No. 3, 2008, pp. 153–63.

13 SJ Neuhaus, NI Klinge, RM Mallet and DHM Saul, ‘Adaptive Campaigning: Implications for Operational Health Support’, Australian Army Journal, Vol. V, No. 3, 2008, pp. 119–40.

14 RG Coyle, ‘Practical Strategy: Structured Tools and Techniques’, Pearson Education, Financial Times Prentice Hall Special Edition, Harlow, Essex, UK, 2004; and RG Coyle, A Systems Description of counter Insurgency Warfare, Policy Sciences 18, 1985, pp. 55–78 (revised version of 1983 University of Bradford publication).

15 S Keller-McNulty et al., ‘Rare Events’, JASON, The MITRE Corporation, McLean, VA, USA, 2009.

16 RG Coyle, ‘Practical Strategy: Structured Tools and Techniques’, Pearson Education, 2004, pp. 29–30.

17 RG Coyle, ‘A Systems Description of Counter Insurgency Warfare’, Policy Sciences 18, 1985, pp. 55–78 (revised version of 1983 University of Bradford publication).

18 Duncan Tailby, Geoff Coyle and Andrew Gill, ‘The Application of Influence Diagrams for the Development of Military Experiments’, Proceedings of the 21st International Conference of the System Dynamics Society, New York, July 20–24 2003.

19 Fabio A Diaz, ‘Rethinking the Conflict Trap: System Dynamics as a Tool to Understanding Civil Wars – the Case of Colombia’, Proceedings of the 26th International Conference of the System Dynamics Society, Athens, Greece, July 20–24 2008.

20 Brett Pierson, ‘A System Dynamics model of the FM 3-24 COIN Manual’, Military Operations Research Society Workshop on Improving Cooperation Among Nations in Irregular Warfare Analysis, 2007, Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, CA, USA, accessed 2 November 2010 <http://www.ndu.edu/CTNSP/docUploadedZ//HSCB%20COIN%20-%20CDR%20Brett%20…;; accessed 2 November 2010 <http://msnbcmedia.msn.com/i/MSNBC/Components/Photo/_new/Afghanistan_Dyn…;.

21 Jim Baker, ‘Systems Thinking and Counterinsurgencies’, Parameters, 2006, pp. 26–43; A Grynkewich and C Reifel, ‘Modeling Jihad: A System Dynamics Model of the Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat Financial Subsystem’, Strategic Insights, Vol. V, 2006; J Bradley Morrison, Daniel Goldsmith and Michael Siegel, ‘Dynamic Complexity in Military Planning: A Role for System Dynamics’, Proceedings of the 26th International Conference of the System Dynamics Society, Athens, Greece, July 20–24 2008; WE Crane, A System Dynamics Framework for Assessing Nation-Building in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, US Army War College, Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, 2009; and David Schoenwald, Curtis Johnson, Len Malczynski and George Backus, ‘A System Dynamics Perspective on Insurgency as a Business Enterprise’, Proceedings of the 27th International Conference of the System Dynamics Society, Albuquerque, New Mexico, July 26–30 2009.

22 Daniel Bilusich, Fred DJ Bowden and Svetoslav Gaidow, ‘Influence Diagram Supporting the Implementation of Adaptive Campaigning’, Proceedings of the 28th International Conference of The System Dynamics Society, Seoul, Korea, July 25–29 2010, accessed 7 Jan 2011 <http://www.systemdynamics.org/conferences/2010/sessions_thread.html.

23 Australian Army, 2009, Adaptive Campaigning 09

24 Australian Army, ‘Army Operating Concept Joint Land Combat, Draft version 1.1’, Force Development Group, Land Warfare Development Centre, Puckapunyal, Victoria, 24 July 2008; accessed 9 January 2009, <http://intranet.defence.gov.au/DRMS/uA8551/I456189.doc>; Australian Army, ‘Army Operating Concept Population Protection, Draft version 1.1’, Force Development Group, Land Warfare Development Centre, Puckapunyal, Victoria, 24 July 2008; accessed 9 January 2009, <http://intranet.defence.gov.au/DRMS/uA8551/I456178.doc>; Australian Army, ‘Army Operating Concept Public Information, Draft version 1.1’, Force Development Group, Land Warfare Development Centre, Puckapunyal, Victoria, 24 July 2008; accessed 9 January 2009, <http://intranet.defence.gov.au/DRMS/uA24434/I456500.doc>; Australian Army, ‘Army Operating Concept Population Support, Draft version 1.1’, Force Development Group, Land Warfare Development Centre, Puckapunyal, Victoria, 24 July 2008; accessed 13 January 2009, <http://intranet.defence.gov.au/DRMS/uA19730/I456190.doc>; and Australian Army, ‘Army Operating Concept Indigenous Capacity Building, Draft version 1.1’, Force Development Group, Land Warfare Development Centre, Puckapunyal, Victoria, 24 July 2008; accessed 9 January 2009, <http://intranet.defence.gov.au/DRMS/uA8551/I456521.doc>.

25 Daniel Bilusich et al., ‘Influence Diagram Supporting the Implementation of Adaptive Campaigning’.

26 Thomas J Sills, 2009, ‘Counterinsurgency Operations in Baghdad: The Actions of 1-4 Cavalry in the East Rashid Security District’, Military Review, May-June 2009, pp. 97–105, accessed 21 July 2009 <http://usacac.army.mil/CAC2/MilitaryReview/Archives/English/MilitaryRev…;.

27 Daniel Bilusich et al., ‘Influence Diagram Supporting the Implementation of Adaptive Campaigning’; and Daniel Bilusich, Fred DJ Bowden and Svetoslav Gaidow, ‘The Role of Influence Diagrams in Implementing Adaptive Campaigning’, Full Spectrum Threats: Adaptive Responses, Proceedings of the Land Warfare Conference, Brisbane, Australia, 16–19 November 2010, pp. 522–32.

28 Daniel Bilusich, Fred DJ Bowden and Svetoslav Gaidow, ‘Applying Influence Diagrams to Support Collective C2 in Multinational Civil-Military Operations’, Proceedings of the 16th ICCRTS, Québec City, Canada, 21–23 June 2011, <http://www.dodccrp.org/events/16th_iccrts_2011/html_post_conference/ind…;.

29 Daniel Bilusich, Fred DJ Bowden and Svetoslav Gaidow, ‘The Role of Influence Diagrams in Implementing Adaptive Campaigning”, pp. 522–32.

30 Australian Army, ‘Army Operating Concept Joint Land Combat, Draft version 1.1’

31 Australian Army, Army Operating Concept Population Protection, Draft version 1.1

32 Australian Army, ‘Army Operating Concept Public Information’.

33 Cheryl L Hetherington, Modeling Transnational Terrorists’ Center of Gravity: An Elements of Influence Approach, Master’s thesis in the school of Engineering and Management, Air Force Institute of Technology, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, OH, USA, 2005; Jim Baker, ‘Systems Thinking and Counterinsurgencies’, Parameters, 2006, pp. 26–43; and Ferdinand Maldonado, The Hybrid Counterinsurgency Strategy: System Dynamics Employed to Develop a Behavioral Model of Joint Strategy, Master’s thesis in the school of Engineering and Management, Air Force Institute of Technology, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio, 2009.

34 Australian Army, ‘Army Operating Concept Population Support, Draft version 1.1’

35 Australian Army, ‘Army Operating Concept Indigenous Capacity Building, Draft version 1.1’, Force Development Group, Land Warfare Development Centre, Puckapunyal, Victoria, 24 July 2008.

36 Australian Army, 2009, Adaptive Campaigning 09: Army’s Future Land Operating Concept, pp. 29–30.