Abstract

Lessons learned by the United States in the global war on terror and in overseas contingency operations underscore the value of intelligence information gleaned from the exploitation of captured enemy personnel, equipment, and materiel. A key element of successful exploitation is accurately categorising information by intelligence discipline in order to apply the correct resources towards the exploitation effort and maximize exploitation potential. In light of these revelations, it is time to review the existing intelligence disciplines to determine whether a new intelligence discipline– exploitation intelligence or ‘EXINT’– should be added to the disciplines currently in existence.

Framing the Problem

At the 2009 Document and Media Exploitation (DOMEX) Conference hosted by the National Ground Intelligence Center, Colonel Joseph Cox argued for the establishment of DOMEX as a separate intelligence discipline, which he named ‘document and media intelligence’ (DOMINT). At that conference and in a subsequent article published in the Military Intelligence Professional Bulletin1, Colonel Cox laid out his reasoning for placing DOMEX on par with the seven existing intelligence disciplines.2 As I considered Colonel Cox’s ideas and related them to my own observations in Iraq and Afghanistan and my experiences as a career Army intelligence officer, I was convinced of the utility of DOMINT. As I thought more about it, however, I began to wonder if DOMINT could in fact stand alone as an intelligence discipline, or if DOMINT would better serve the intelligence community as a component or sub-discipline of an entirely separate intelligence discipline, one centred on the exploitation of captured enemy personnel and materiel. I named this potential new discipline ‘exploitation intelligence’ or EXINT.

The process of exploiting captured enemy personnel and materiel for intelligence purposes dates back thousands of years. One of the earliest examples comes from the Egyptians, who exploited the captured iron weapons of their Hittite opponents in order to improve their own weapons, made of inferior bronze.3 More recently, the fledgling US Army made use of captured enemy personnel, equipment, and documents during the American Revolution, and the practice expanded and continues to the present day. In the modern era, information derived from the interrogation of captured enemy personnel and the exploitation of their possessions contributed to the capture of Saddam Hussein4, the death of Abu Musab al Zarqawi5, and the killing of Osama bin Laden6. These examples underscore the utility and value of the exploitation process and intelligence derived from exploitation methods.

Finding Common Ground

It is important to accurately define, describe, and categorise intelligence information in order to apply the correct resources against it and to utilise it to its fullest extent. This is because inconsistent, imprecise, or inaccurate terms, procedures, and policies within the intelligence community cause redundancies of effort and inefficiencies in supporting the intelligence mission. In researching this subject it became apparent that the intelligence community is not always in agreement on descriptions, doctrine or definitions related to intelligence. For example, the US Army states that there are nine intelligence disciplines, while its joint military publication on intelligence states there are seven7 and the Federal Bureau of Intelligence promulgates five ‘intelligence collection disciplines’.8 Furthermore, the Department of Homeland Security is pushing for the creation of ‘Homeland Security Intelligence (HSINT) and also makes mention of ‘security intelligence’, ‘domestic intelligence’, and ‘domestic national security intelligence’.9

... inconsistent, imprecise, or inaccurate terms, procedures, and policies within the intelligence community cause redundancies of effort ...

Given the incfonsistency of common terms within the intelligence community, I had to decide on a common reference in order to deconflict terms for this article. Because elements of the US Department of Defense comprise more than half the seventeen organisations of the intelligence community (sixteen members plus the Office of the Director of National Intelligence)10, I felt it was logical to use Department of Defense references in situations where I encountered conflicting information. As a result, this article relies on joint military publications, specifically Joint Publication 2-0 (JP 2-0), Joint Intelligence, published in June 2007, as the most authoritative source of doctrinal intelligence-related information. In cases where a useful contrast to JP 2-0 is provided by other sources, or where existing doctrine falls short, this article provides those sources as well as alternative definitions and descriptions based on compilations of sources.

The Purpose of Intelligence

To adequately assess the potential value of EXINT as a separate intelligence discipline, an important starting point involves an understanding of the purpose of intelligence. Unfortunately, there does not appear to be a consistent description of the purpose of intelligence across the intelligence community. Some definitions of the purpose of intelligence are very detailed and complex, while others can explain the purpose of intelligence in a handful of words. Most military definitions of the purpose of intelligence revolve around derivatives of ‘informing the commander’ or ‘driving operations’. This line of thinking is typified by the US Army’s description of the purpose of intelligence:

The purpose of intelligence is to provide commanders and staffs with timely, relevant, accurate, predictive, and tailored intelligence about the enemy and other aspects of the AO [area of operations]. Intelligence supports the planning, preparing, execution, and assessment of operations. The most important role of intelligence is to drive operations by supporting the commander’s decision-making.

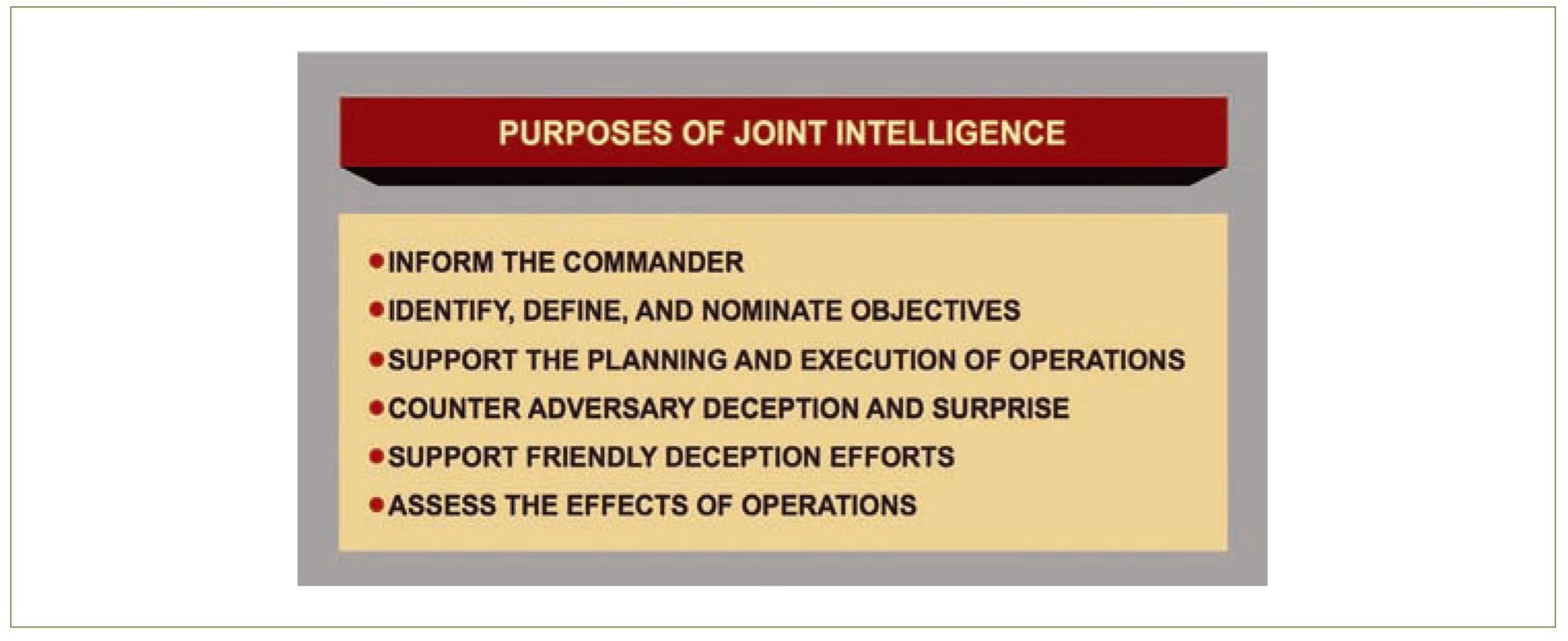

Additionally, the purpose of intelligence as specified by JP 2-0 is to:

...inform the commander; identify, define, and nominate objectives; support the planning and execution of operations; counter adversary deception and surprise; support friendly deception efforts; and assess the effects of operations on the adversary.11

JP 2-0 lacks a holistic definition of the purpose of intelligence because it is military-centric and can not be easily applied across the civilian components of the intelligence community. The JP 2-0 definition also rather conspicuously omits the mission of counterintelligence. Moreover, while the above definitions are sufficient in military applications, they do not accurately represent the expectation most

Figure 1. Purposes of joint intelligence.12

US citizens have of the intelligence enterprise, which in most cases might simply be to prevent surprise. A concept of intelligence that is better suited for the entire intelligence community can be found in Mark Lowenthal’s often-cited textbook, Intelligence: From Secrets to Policy:

Intelligence is the process by which specific types of information important to national security are requested, collected, analyzed, and provided to policy makers; the products of that process; the safeguarding of these processes and this information by counterintelligence activities; and the carrying out of operations as requested by lawful authorities.13

Lowenthal’s definition is much better than JP 2-0, but is still somewhat lacking. Combining all the available definitions of the purpose of intelligence, I compiled the following:

The purpose of intelligence is to enable ‘decision advantage’14 by disseminating timely, accurate, predictive and contextualized assessments of the operational environment in order to provide early warning and prevent surprise, and to prevent the compromise of intelligence products and the sources and methods of collection.15

The above definition encompasses all the existing intelligence disciplines, including counterintelligence which, as previously noted, seems to have been omitted in the military definitions of the purpose of intelligence. It also makes the definition more encompassing by removing the stipulation that intelligence is for ‘commanders’ or ‘policy makers’, thereby recognising the fact that anyone can be a legitimate consumer of intelligence, including other intelligence professionals.

Some terms in the above definition of the purpose of intelligence warrant further explanation. The best definition I found for ‘decision advantage’ was the ‘...ability of the United States to bring instruments of national power to bear in ways that resolve challenges, defuse crises, or deflect emerging threats’.16 This is significant because intelligence exists not for its own sake, but in order to provide decision-makers with the best information possible so that they may make the best decision possible. Additionally, in the definition above, ‘early warning’ provides intelligence related to specific anticipated events, such as fixing the enemy in time and space in order to make this enemy targetable, while ‘preventing surprise’ refers to the efforts to determine and mitigate enemy plans and intentions. In short, ‘early warning’ is focused on the enemy, while ‘preventing surprise’ is friendly forces-centric.

The Intelligence Disciplines

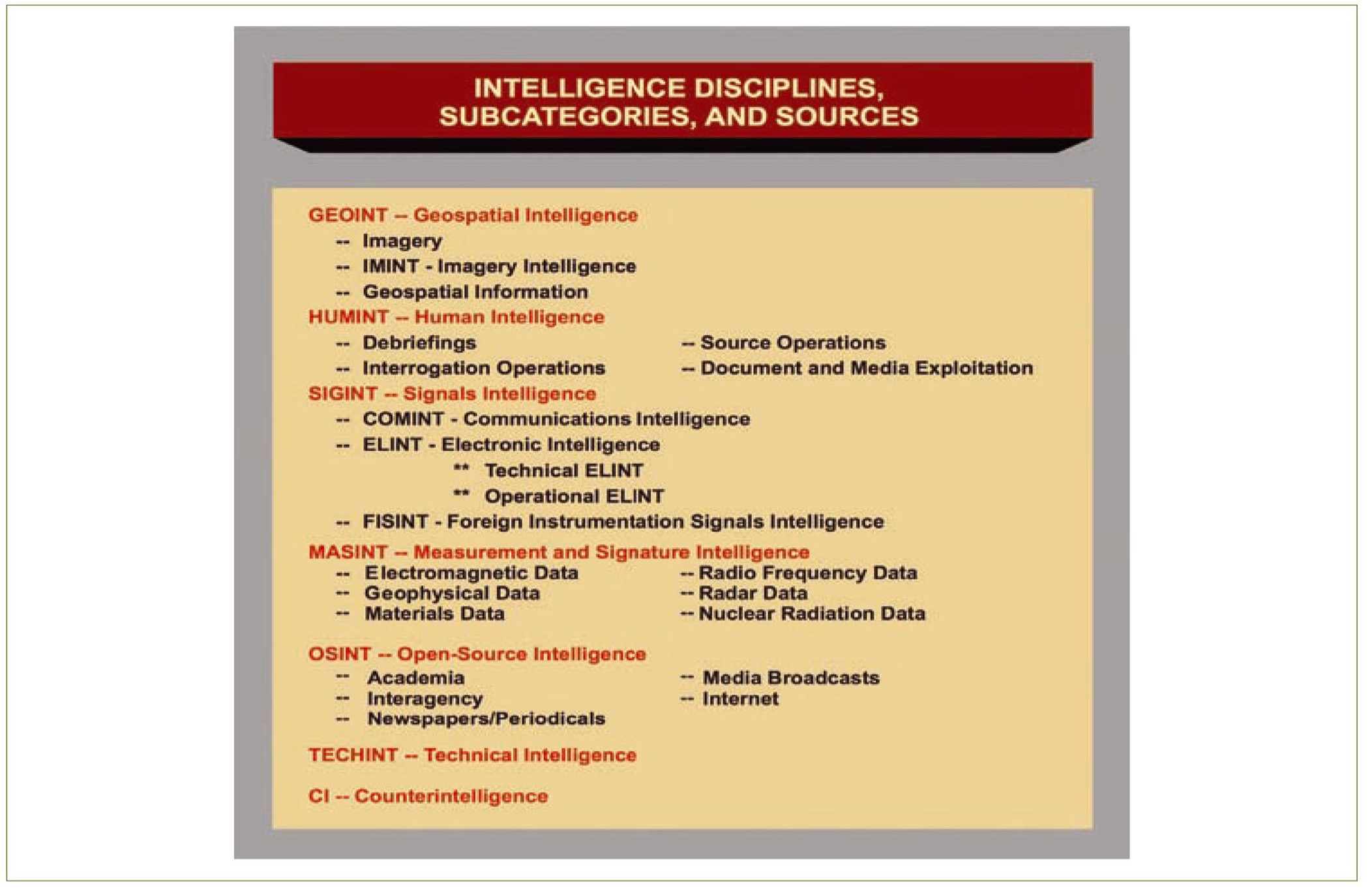

With the purpose of intelligence established, we can move on to a description of what makes an intelligence discipline, and explore the seven joint intelligence disciplines currently in existence. An intelligence discipline is a ‘well defined area of intelligence planning, collection, processing, exploitation, analysis, and reporting using a specific category of technical or human resources’.17 According to JP 2-0, the extant joint intelligence disciplines are counterintelligence (CI), human intelligence (HUMINT), geospatial intelligence (GEOINT), open-source intelligence (OSINT), signals intelligence (SIGINT), measurement and signature intelligence (MASINT), and technical intelligence (TECHINT).18 There are several sub-disciplines within these, as shown in Figure 2.

The way the intelligence community distinguishes intelligence disciplines from one another is based on how the information is collected, instead of what is collected. By doing this, it is easy to see how a strong case can be made that the same collection effort might fall into different intelligence disciplines, or ‘-INTs’. A useful example may be to consider a telephone conversation between two people. If one of those individuals uses the phone to pass along information to a witting recipient on the other end of the line, this is easily recognised as HUMINT. But if that same conversation took place between two unwitting participants and was intercepted by a third party, the information garnered would be SIGINT. Using a similar example, if a photograph of a military installation is taken by a classified overhead collection platform, it would be imagery intelligence (IMINT). But if a photo of the exact same installation were downloaded from the Internet, it would be considered OSINT and if it was delivered by a paid source, it would be HUMINT. A radar return showing an enemy armored convoy is considered IMINT, but a case can be made that, since radar measures the return of radio waves, the information is collected as a result of MASINT.

The way the intelligence community distinguishes intelligence disciplines from one another is based on how the information is collected

Figure 2. Intelligence disciplines and sub-disciplines.19

The above examples are far from semantic; accurate descriptions of intelligence disciplines are tied to proper collection and classification of information, as well as training, equipping, and fielding the right kinds of intelligence platforms and personnel. Moreover, for an intelligence discipline to reach its maximum level of effectiveness, it must be defined precisely and supported, resourced, and utilised properly. It is with that in mind that I will now turn my attention towards explaining EXINT.

Description of Exploitation Intelligence

Joint Publication 1-02, ‘Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Related Terms’, explains ‘exploitation’ in part as ‘taking full advantage of success in military operations, following up initial gains, and making permanent the temporary effects already achieved’ and ‘taking full advantage of any information that has come to hand for tactical, operational, or strategic purposes’.20 This is a very useful definition to use when exploring the potential utility of EXINT. By exploiting captured enemy personnel and materiel, EXINT would make permanent the temporary gains achieved in the seizure of those personnel and equipment by extracting the maximum value from those items. This in turn would allow US forces to take ‘full advantage’ of what has ‘come to hand’ by providing more thorough intelligence information to support decision-makers at all levels. Combining the definition of exploitation with the definition of the purpose of intelligence provided earlier in this article and putting it into the context of ‘exploitation intelligence’, the definition of EXINT is as follows:

Exploitation Intelligence (EXINT): the process by which captured enemy personnel and materiel are exploited for intelligence purposes as part of the all-source effort to provide ‘decision advantage’ to decision-makers at all levels. EXINT consists of four parts: biometrics (BIOINT), detainee interrogations (DETINT), document and media exploitation (DOMINT), and technical intelligence (TECHINT).

If EXINT were to become a separate -INT, what would comprise the new discipline? To begin with, TECHINT, already established as a separate intelligence discipline, would become a sub-discipline and be subsumed under EXINT. EXINT would also encompass interrogations, which would become a separate sub-discipline: detainee exploitation, or DETINT. Document and media exploitation intelligence, or DOMINT, would move from HUMINT, as would biometrics intelligence or BIOINT. TECHINT, DETINT, DOMINT, and BIOINT would comprise the four elements of EXINT.

EXINT is differentiated from other -INTs by the way in which it is gained from personnel or enemy equipment that is in friendly hands; information collected ‘in the wild’ belongs to another discipline. For example, when the exploitation of a captured enemy communication device yields a specific contact number, then that is EXINT. When collection is applied against that number, the resulting information is SIGINT. Information from an enemy detainee is EXINT, while information elicited from an enemy politician or soldier by a collector is still HUMINT. Intelligence information gained from the technical evaluation of a missile fired by the enemy would be MASINT, whereas the technical information derived from that same missile would be EXINT if it were to occur while the missile was in friendly hands.

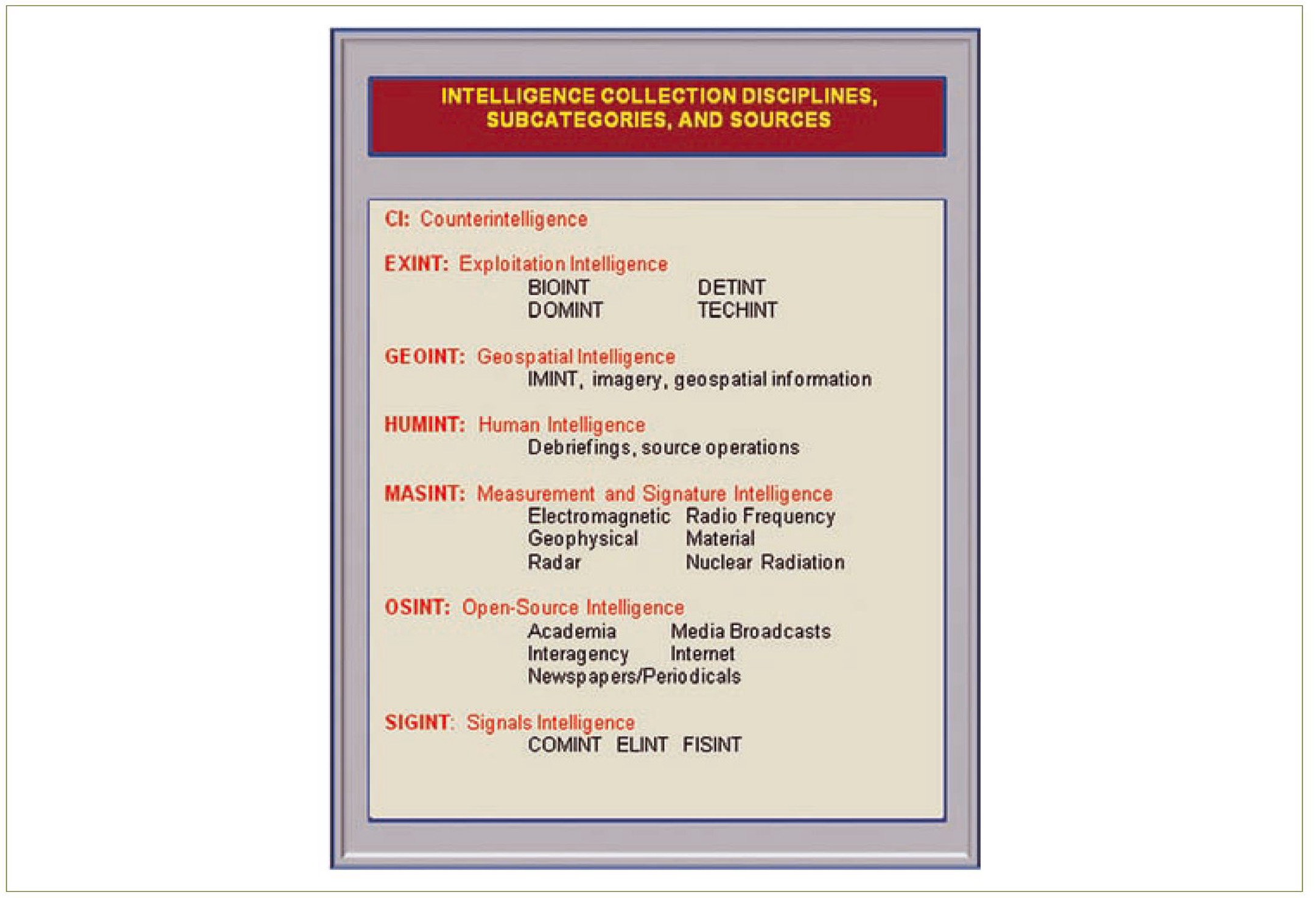

If EXINT were to become its own discipline, little in doctrine would have to change. CI, GEOINT, OSINT, and MASINT would likely be completely unaffected by EXINT. HUMINT would lose three components: biometrics, interrogations, and DOMEX. Doctrine would need to further change to reflect the establishment of BIOINT, DOMINT, and DETINT as official sub-disciplines under EXINT. The-INT most affected by EXINT would be TECHINT, because it would lose its status as an independent discipline and would fall under EXINT. HUMINT would also be affected because interrogations are currently a HUMINT function. Change would be required in order to implement EXINT, but most if not all of these changes should be transparent to the majority of the intelligence community and the intelligence consumers that it supports. If JP 2-0 were revised to take the above changes into account, it might look something like Figure 3.

If EXINT were to become its own discipline, little in doctrine would have to change.

Conclusion

If the purpose of intelligence is to enable ‘decision advantage’ at all levels, and if an intelligence discipline is defined as collection in a ‘specific category of technical or human resources’, then EXINT (comprised of BIOINT, DETINT, DOMINT, and TECHINT) would appear to be able to stand on its own as a new intelligence discipline.

Figure 3. Revised JP 2-0 intelligence disciplines

Although the potential value of EXINT is clear through myriad historical examples, more research is required in order to determine if the cost/benefit analysis of establishing a new intelligence discipline weighs in favour of EXINT, or whether the tasks that this article ascribes to EXINT are better accomplished by the intelligence disciplines already in existence. At this point however, when considered against the doctrinal definition of what comprises an intelligence discipline, the validated contribution of intelligence gained from exploitation methods, and the intuitive utility of grouping ‘like functions’ together, it appears likely that EXINT is warranted.

Endnotes

1 Joseph Cox, ‘DOMEX: The Birth of a New Intelligence Discipline’, Military Intelligence Professional Bulletin, April–June 2010, p.22.

2 Joint publication 2-0, ‘Joint Intelligence’, June 2007, <http://www.dtic.mil/doctrine/new_pubs/jp2_0.pdf>, accessed 4 October 2010.

3 Robert Clark, The Technical Collection of Intelligence, CQ Press, Washington, DC, 2011, p. 247.

4 BBC news, ‘How Saddam Hussein Was Captured’, 15 December 2003, <http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/3317881.stm>, accessed 20 April 2011.

5 Mark Bowden ‘The Ploy’, The Atlantic, May 2007, <http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2007/05/the-ploy/5773/>, accessed 20 April 2011.

6 Adam Goldman and Matt Apuzzo, ‘How Was Osama bin Laden Caught? One Small Mistake’, The Associated Press, 2 May 2011, <http://www.uticaod.com/news/x449043929/How-was-Osama-bin-Laden-caught-O…;, accessed 4 May 2011.

7 JP 2-0, ‘Joint Intelligence’, Department of Defense, June 2007, p. 1–5.

8 FBI, Director of Intelligence, ‘Intelligence Collection Disciplines (INTs)’, <http://www.fbi.gov/about-us/intelligence/disciplines>, accessed 20 April 2011.

9 Mark A Randol, ‘Homeland Security Intelligence: Perceptions, Statutory Definitions, and Approaches’, Congressional Research Service, 14 January 2009, p. 6.

10 Intelligence.gov, ‘About the Intelligence Community’, <http://www.intelligence.gov/about-the-intelligence-community/>, accessed 28 April 2011.

11 JP 2-0, p. 1–3.

12 Ibid, p. 1–3.

13 Mark Lowenthal, Intelligence: From Secrets to Policy, Fourth Edition, CQ Press, Washington, DC 2009, p. 8.

14 JM McConnell, ‘Vision 2015’, (undated) <http://www.dni.gov/Vision_2015.pdf>, accessed 13 April 2011.

15 Refined definition of the purpose of intelligence, compiled by the author from a variety of sources.

16 ‘Vision 2015’, p. 8.

17 Joint Publication 1-02, ‘Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Related Terms’, Department of Defense, 17 October 2008, p. 181.

18 JP 2-0.

19 JP 2-0, p. 1–6.

20 JP 1-02, p. 132