Abstract

Operation LAVARACK was an ambushing and reconnaissance-in-force operation conducted by the 6th Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment – New Zealand (Anzac) in Area of Operations (AO) Vincent in Phuoc Tuy Province from 30 May to 1 July 1969. During thirty- two days of continuous patrolling and ambushing, 6RAR-NZ defeated in battle two main force regiments and a district company, captured and destroyed hundreds of enemy bunkers, disrupted the Viet Cong administrative system in Phuoc Tuy Province by denying the enemy his vital lines of communication and supply, and irreparably damaged the military and political position of the Viet Cong in Phuoc Tuy Province.

Introduction

In June 2009, at a gathering of Vietnam veterans at the Australian War Memorial, a senior military historian described Operation LAVARACK as a ‘spectacularly effective, milestone operation’.1 Apart from this one public recognition, Operation LAVARACK’s achievements have been lost to history. During the past forty years Australian military operations in Vietnam have been characterised by Long Tan, Coral, Balmoral and Binh Ba. These were striking successes, deserving of distinction, but their dramatic nature has distracted historical attention from the significant military successes of Operation LAVARACK. The aim of this article is to correct this historical omission.

There are many convincing reasons why Operation LAVARACK should be recognised as a uniquely successful operation. During thirty-two days of continuous ambushing and patrolling, 6 Royal Australian Regiment – New Zealand (Anzac) Battalion (6RAR-NZ) attacked and defeated 33 North Vietnamese Army Regiment in a series of continuous company actions, attacked and ambushed 274 Viet Cong Regiment on three occasions, and drove C41 Chau Duc Viet Cong District Company from its ‘home base’ bunkers. On conclusion of Operation LAVARACK on 1 July, 6RAR-NZ soldiers had been involved in eighty-five contacts with the enemy: 102 North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong had been killed in action and at least twenty-two wounded, ten had been taken prisoner and one surrendered. Seventy-one weapons and 330 bunkers had been captured, and 202 destroyed.2 The 6RAR-NZ losses were three killed in action and twenty-nine wounded.

An additional unexpected outcome of Operation LAVARACK was that it brought about a severe disruption of the Viet Cong administrative system in Phuoc Tuy Province. Supply points were destroyed, vital lines of communication were denied, the logistics system was irreparably damaged, and rear services groups were unable to carry out their objective— support of main force Viet Cong units in Phuoc Tuy, Bien Hoa and Long Khanh Provinces.

These were remarkable results. They had a disastrous effect on Viet Cong military and political activities in Phuoc Tuy Province.

The Plan

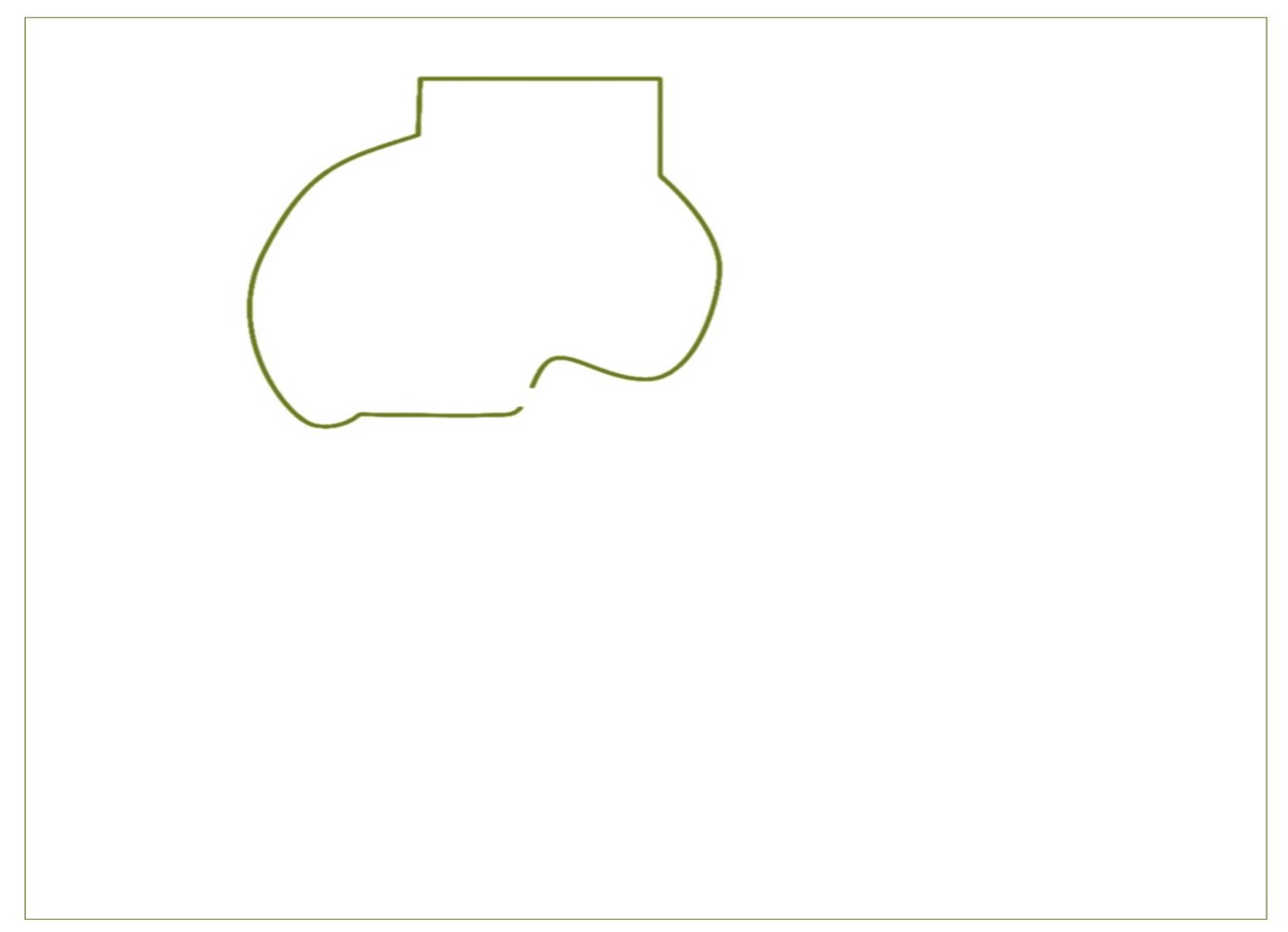

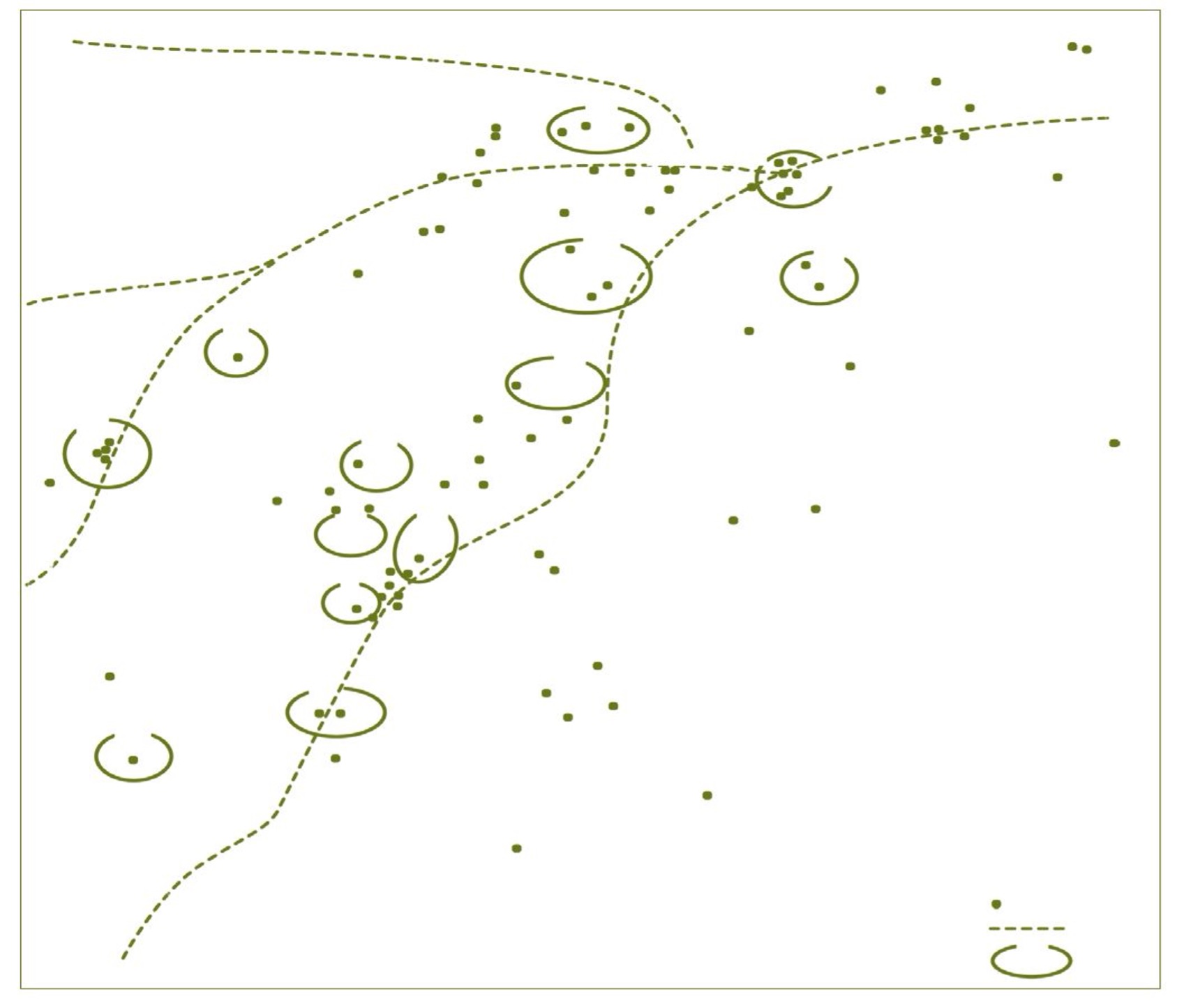

Operation LAVARACK was an ambushing and reconnaissance-in-force operation conducted by 6RAR-NZ3 in Area of Operations (AO) Vincent in Phuoc Tuy Province from 30 May to 1 July 1969 (Map 1).4 The mission was ‘to ambush major Viet Cong routes’ and the plan was based on a captured map which showed their general directions. The commanding officer of 6RAR-NZ, Lieutenant Colonel Butler, placed all five rifle companies on these routes, and positioned Fire Support Patrol Base (FSPB) Virginia in the centre of AO Vincent where it could provide artillery fire support over the whole of the area of operations (Map 2).5 AO Vincent was unusually large when compared with previous task force operations, resulting in the five rifle companies being widely dispersed throughout western and northern Phuoc Tuy Province. This broad spread of companies was of concern to Brigadier Pearson, the commander of 1 Australian Task Force (1ATF), who thought separation would minimise mutual support. Nevertheless, it was precisely appropriate to the mission—to cover all enemy routes at the same time. It was an unexpected tactic and achieved surprise.

Map 1. Area of Operations (AO) Vincent.

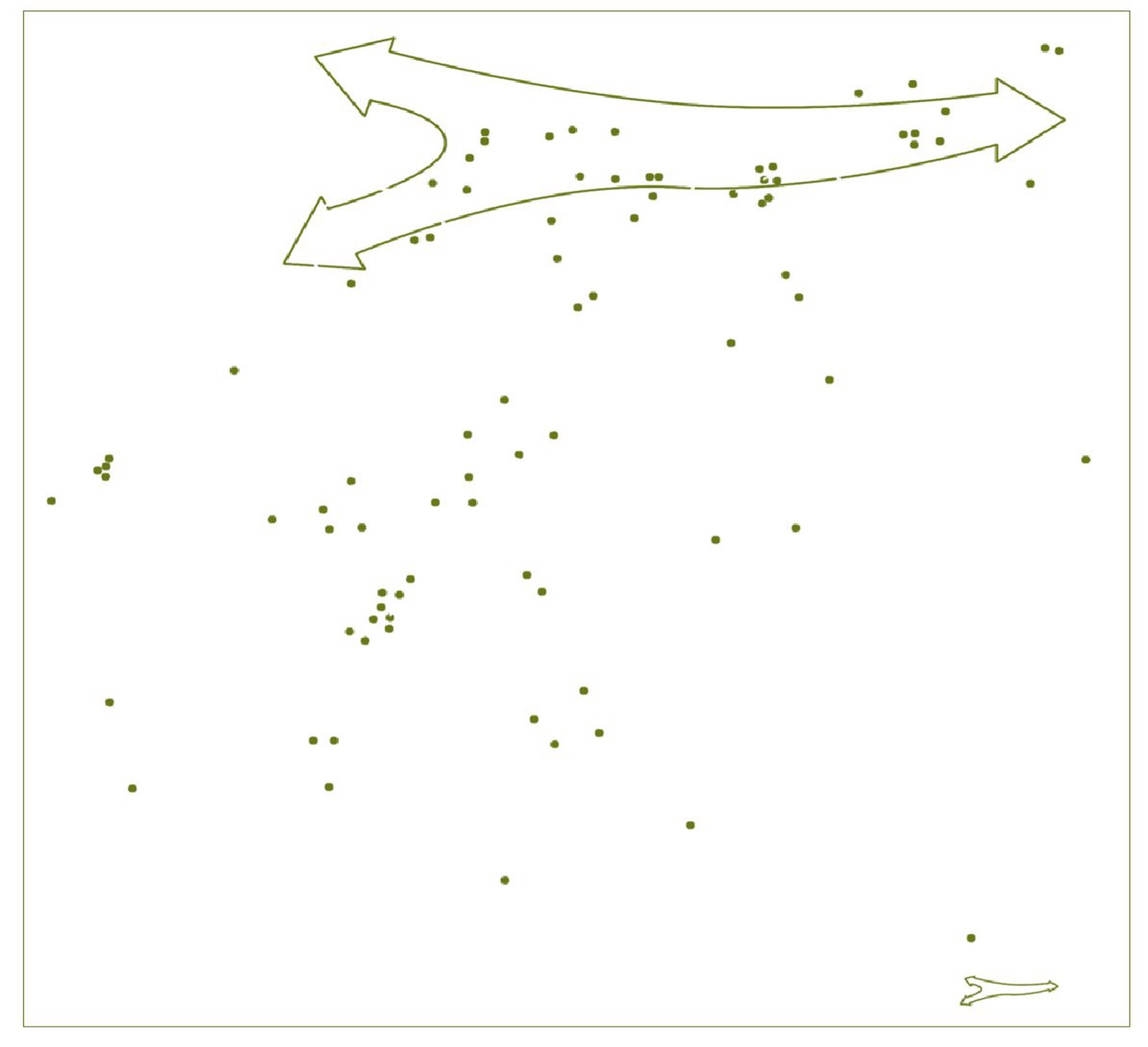

Map 2. 6RAR-NZ(Anzac) Battalion Deployment.

The Enemy

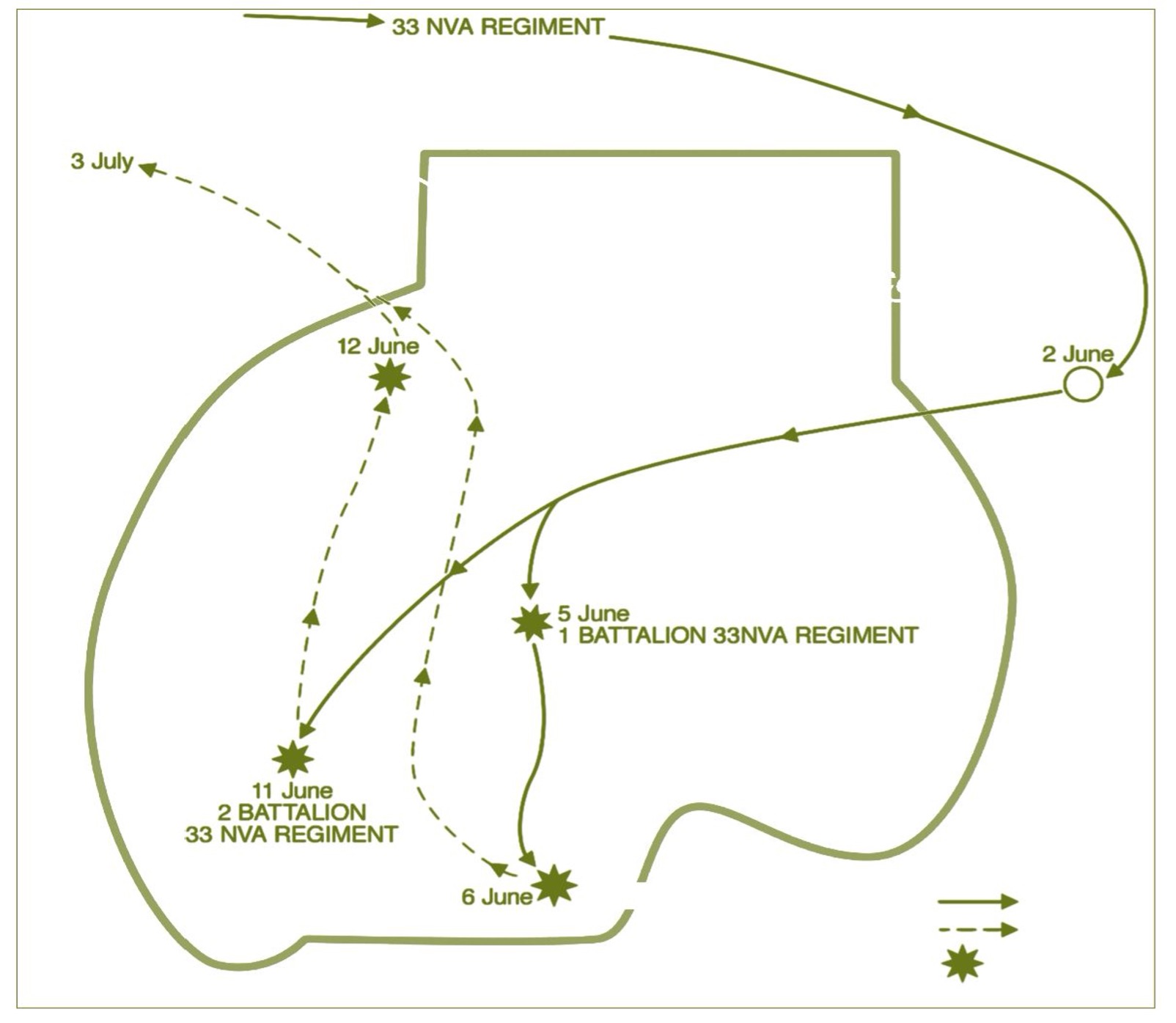

During Operation LAVARACK there were four Viet Cong military groups that could be expected to operate against 6RAR-NZ. The first was 33 NVA Regiment, a main force unit of 1130 North Vietnamese regulars organised into three battalions and eight support companies: 82mm mortar, 12.7mm heavy machine gun, 75mm recoilless rifle, communications, transport, medical, rear services and engineer companies. 33 NVA Regiment had been in Phuoc Tuy Province only once prior to Operation LAVARACK; on 12 May 1969 it had briefly crossed the northern boundary without any military success. In late May 1969, aerial sensors had detected its regimental headquarters and two battalions west of the American base Blackhorse in Long Khanh Province (Map 3), and a third battalion near the Viet Cong logistics centre in Nui May Tao (Map 1).

Map 3. Area of Operations (AO) Vincent, 33 NVA Regiment - 274 VC Regiment.

The second main force unit was 274 VC Regiment, about 900 strong. In May 1969 its headquarters was in the Hat Dich area in Bien Hoa Province, one of its battalions was identified near the Binh Son Rubber Plantation in Long Khanh Province, and the remainder was in a ‘home base’ about ten kilometres west of Blackhorse. The third enemy unit was D440 Local Force Battalion of 200 guerrillas dispersed in bunkers, tunnels and hides along Route 2 in Phuoc Tuy Province; and the fourth was C41 Chau Duc District Company, about sixty strong and known to be in a ‘home base’ north of the Nui Thi Vai and Nui Dinh Hills (Map 1).

Main force units operating in Military Region T76 were supported by the Ba Long Province Rear Services Group, an administrative organisation based in Nui May Tao.7 In late May it was reinforced by 84 Rear Services Group. These groups were responsible for the procurement, storage, maintenance, control and delivery of all war stores and communal services such as medical, surgical and hospital treatment.

The east-west route across the north of Phuoc Tuy Province (Map 2) connected the great rear services storehouses in Nui May Tao to North Vietnamese and Viet Cong main force units in Phuoc Tuy, Bien Hoa and Long Khanh Provinces.8 It passed through the gap between the 199 Light Infantry Brigade (US) area of responsibility in Long Khanh Province and the 1ATF area of responsibility in Phuoc Tuy Province, and was the Viet Cong’s critical ground for the efficient delivery of services essential for their military and administrative survival.

On 28 May HQ 1ATF indicated to 6RAR-NZ that the locations of most enemy forces usually found in Phuoc Tuy Province had been identified, that it was unlikely any main force units would enter Phuoc Tuy Province or concentrate for a major operation during June, and that local forces would not be a threat to 6RAR-NZ during Operation LAVARACK.9 Consequently, the HQ IATF assessment was that AO Vincent would be a suitable ‘work-up’ area for an ‘introductory’ operation by 6RAR-NZ. It would allow the battalion time to quietly ‘settle in’, become accustomed to unfamiliar conditions and test its operational drills and tactical procedures in a relatively ‘safe’ area. As a result, Brigadier Pearson casually told Lieutenant Colonel Butler to ‘nip in there and bang about a bit’.10

The Arrival of 33 NVA Regiment in AO Vincent

However, after 6RAR-NZ had deployed into Operation LAVARACK and contrary to all previous intelligence assessments, the enemy threat changed dramatically on 2 June when 33 NVA Regiment unexpectedly entered Phuoc Tuy Province. Its headquarters and two battalions halted briefly in a concentration area on the Song Rai River where they made final preparations for a bold but high-risk advance into AO Vincent. A signals intelligence operator said:

I will never forget the tension on 2 June 1969 when we briefed the G2 Intelligence and his staff that 33 NVA Regiment had crossed the Song Rai River and was located near Binh Gia Hamlet only a few kilometres from Binh Ba.11

On 3 June the leading battalion crossed Route 2. By last light on 4 June the headquarters, two battalions and at least three heavy weapons companies had occupied prepared bunker systems inside AO Vincent: one near W Company (NZ) about 4000 metres north of FSPB Virginia, the other in B Company’s area of operations 5000 metres west of the village of Xa Binh Ba (Maps 2 and 3).

The reason for 33 NVA Regiment’s entry was primarily political. It was responding to a Central Office for South Vietnam (COSVN) directive that main force units be involved in a series of ‘cyclical high points’ during the communist summer offensive from May to July by demonstrating that ‘the Viet Cong were able to enter villages at will despite the presence of 1ATF and increased pacification effort’.12 The Viet Cong plan was for 1 Battalion 33 NVA Regiment to occupy and proselytise13 Xa Binh Ba in coordination with C41 Chau Duc District Company’s simultaneous occupation of the village of Xa Hoa Long, and for 2 Battalion 33 NVA Regiment to secure a base for their safe withdrawal afterwards.

The subsequent defeat of 33 NVA Regiment was a significant feature of Operation LAVARACK. It was not achieved in one single dramatic action but during a series of four battles which lasted from 3 June when 33 NVA Regiment arrived in AO Vincent until 12 June when it was driven out of Phuoc Tuy Province.

5 June: Slope 30 - The First Battle with 33 NVA Regiment

The first battle began at 1030 hrs on 5 June, when patrols from W Company (NZ) found and attacked 1 Battalion 33 NVA Regiment, two heavy weapons companies and A57 Rear Services Support Company14 in a defended bunker system in thick bamboo about 4000 metres north of FSPB Virginia (Map 3). When W Company penetrated the bunker system, the North Vietnamese reacted with an intense volume of fire from small arms, grenades, 12.7mm heavy machine guns and rocket-propelled grenades from both front and flanks. During the attack, Major Williams, the NZ company commander, engaged the enemy with artillery and two helicopter light fire teams.15 One Bushranger helicopter from the Royal Australian Air Force light fire team was shot down by 12.7mm machine gun fire; the crew were rescued by the 6RAR-NZ anti-tank platoon and the helicopter recovered.

By mid-afternoon, when still involved in a heavy firefight, Major Williams called for an airstrike but due to heavy monsoonal rain, low cloud cover, difficulties of target identification in thick bamboo, and the enemy’s use of different coloured smoke to confuse air support, the Jade air controller cancelled the airstrike at 1737 hrs. At last light, badly battered by W Company’s attack and by accurate and heavy artillery, mortar and light fire team support, the North Vietnamese broke contact, abandoned their bunkers and withdrew, moving southwards in darkness towards their political target, the village of Xa Binh Ba.16

6 June: XA Binh Ba - The Second Battle with 33 NVA Regiment

The second of the continuum of battles was the clearance of the village of Xa Binh Ba. At first light on 6 June, delayed and disorganised by W Company’s attack the night before, 1 Battalion 33 NVA Regiment entered Xa Binh Ba (Maps 3 and 4). At 0720 hrs a NVA group, on top of a house on the left of Provincial Route 2, fired a rocket-propelled grenade, disabling a Centurion tank passing Xa Binh Ba on its way along Route 2 to FSPB Virginia. The rocket penetrated the tank’s turret and wounded the loader-operator who collapsed across the breech of the main armament, preventing the tank’s turret from traversing. The tank commander instinctively returned fire with bursts from his Browning machine gun, as did the craftsman on the armoured recovery vehicle about 100 metres behind. The recovery vehicle reversed out of the contact area and returned to Nui Dat. The Centurion’s commander ordered his driver to accelerate north along Route 2 to the Duc Thanh Regional Force Post where the wounded operator was evacuated by helicopter. The battle for Xa Binh Ba had begun.

This first rocket was not the result of panic by a lone and nervous Viet Cong but a deliberate act by a well-trained NVA veteran who had selected with care his high firing point on the tiled roof of a house, calculated the distance to the target area with precision, adjusted his sights exactly, and knew where to hit the tank with his first shot.17

Soon after 0800 hrs, Major Ngo, the District Chief, requested assistance from 1ATF, and within minutes Brigadier Pearson instructed Lieutenant Colonel Butler to use 6RAR-NZ to clear the village.18 This was a practical decision because Xa Binh Ba was inside AO Vincent, and 33 NVA Regiment’s presence was an extension of 6RAR-NZ’s ongoing activities for Operation LAVARACK. However, at the time, all 6RAR-NZ companies were involved in close contacts with Viet Cong so at 0820 hrs Brigadier Pearson agreed to the request that the ready reaction force be placed under command of 6RAR-NZ to deal with Xa Binh Ba.19

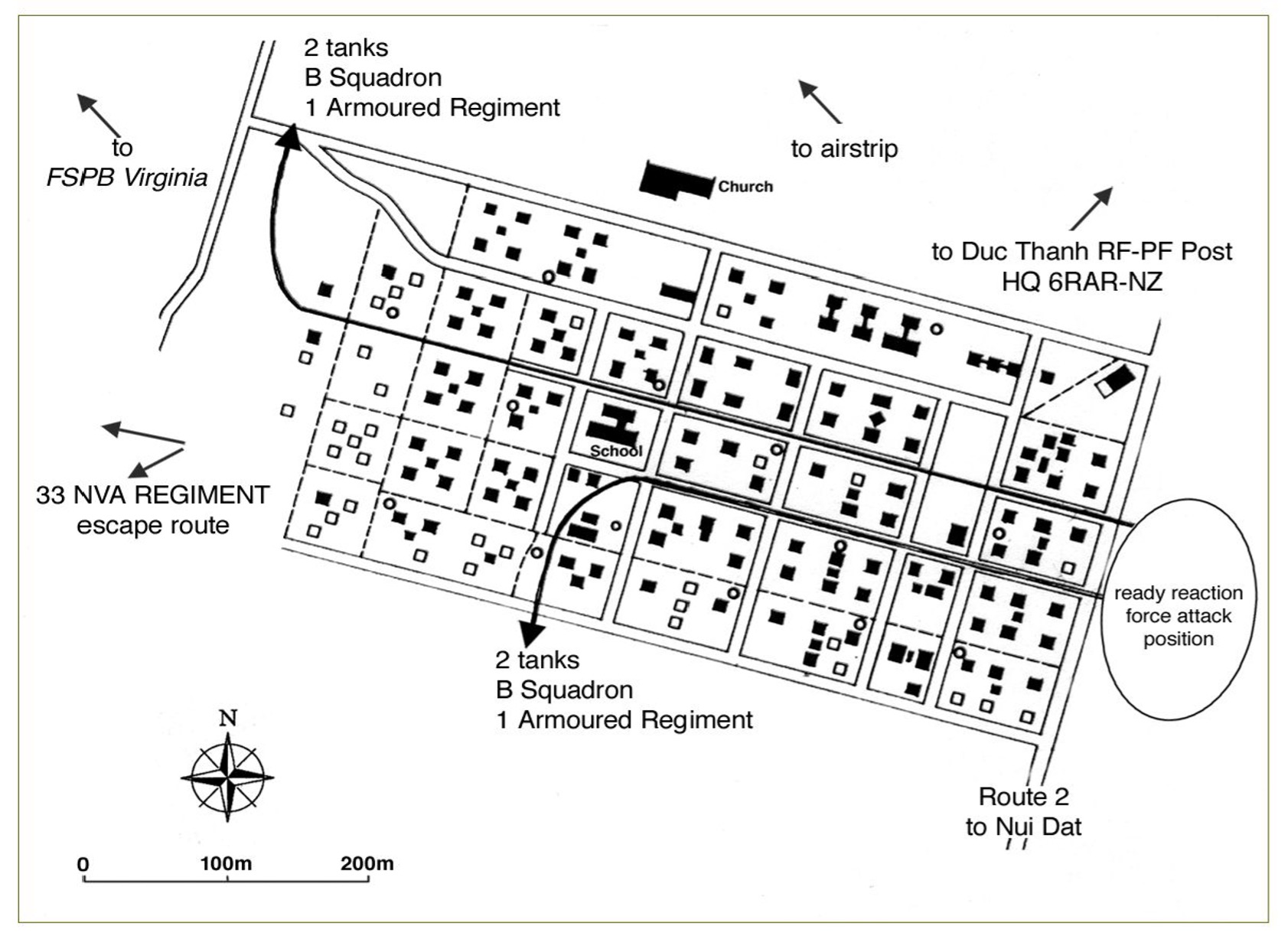

After the ready reaction force had arrived and the district chief was satisfied that as many villagers as possible had been evacuated, Lieutenant Colonel Butler gave the order to attack. At 1130 hrs the ready reaction force crossed Provincial Route 2 and swept into the village from east to west in two mobile columns, each with a half troop of two tanks leading, followed by infantry mounted in armoured personnel carriers (Map 4). The North Vietnamese were not expecting a sudden and vigorous reaction to their occupation and many tried to ‘break out to the south-west’, ‘were trickling out into the rubber to the south-west’ and ‘seeking shelter in the Catholic church to north’. Those who could not escape the tank assault were forced to seek protection in tunnels and bunkers beneath the village.20 By 1230 hrs the battle for Xa Binh Ba had been decided. The tanks had been decisive; they had cleared two routes through the village and drastically reduced 33 NVA Regiment’s ability to respond in any organised military way.21

Map 4. Attack Routes at Binh Ba

At 1300 hrs the involvement of the ready reaction force under command of 6RAR-NZ in Operation LAVARACK ended, the civilian access area around Xa Binh Ba was excised from AO Vincent and named AO Anvil, and the operation was renamed Hammer.22 During the afternoon of 6 June and on 7 June 5RAR, B Squadron 3 Cavalry Regiment and B Squadron 1 Armoured Regiment conducted sweeps and searches to clear surviving North Vietnamese out of spider holes, bunkers and tunnels around and under houses until resistance ended.23

Two external factors affected the action at Xa Binh Ba. First, following its defeat the previous night at Slope 30, 1 Battalion 33 NVA Regiment needed time to reorganise, restructure, resupply and reconsider its plan, a delay which resulted in a late arrival at Xa Binh Ba and consequent haste in defensive preparation.

Second, the occupation of Xa Binh Ba had been coordinated with C41 Chau Duc District Company’s entry into Xa Hoa Long, a tactic which the Viet Cong hoped would split the size and aim of a 1ATF reaction force. However, this stratagem failed. Late in the afternoon of 4 June, A Company 6RAR-NZ found C41 Chau Duc District Company’s home base in a bunker system 5000 metres west of Xa Binh Ba. To gain surprise, the company commander, Major Belt, decided on a silent attack using two platoons: one to assault, the other to give fire support from a flank. The assault platoon was detected by the Viet Cong as it crossed the start line so the platoon commander immediately launched his attack, penetrating well into the bunker system. The Viet Cong replied with automatic weapons, hand grenades, rocket-propelled grenades and small arms fire from the front and flanks and from snipers in trees. Soon both the assault and support platoons were in close contact inside the bunker system and involved in fierce firefights.

The company commander now realised that the bunker system extended over a wider and deeper area than expected and was occupied by a large enemy force. Failing light and monsoonal rain made identification of enemy targets difficult so Major Belt called for close artillery fire support to destroy the bunkers, and withdrew the assault platoon by fire and movement while under attack from three Viet Cong groups firing automatic weapons. Battered by the company attack and artillery fire, the C41 Chau Duc District Company withdrew under the cover of darkness, carrying their casualties and abandoning their bunkers, leaving behind a large amount of ammunition, weapons, documents, maps, clothing and general stores.24 This attack disorganised C41 Chau Duc District Company and delayed its entry into Xa Hoa Long, resulting in the whole of 1ATF ready reaction force being available to be deployed against 1 Battalion 33 NVA Regiment in Xa Binh Ba.25

The military purpose of the Viet Cong occupations of Xa Binh Ba and Xa Hoa Long was not to ‘relieve 6RAR-NZ pressure on its headquarters’; nor were the occupations ‘feints to draw 6RAR-NZ away from 1 Battalion 33 NVA Regiment to allow the remainder ... to cross Route 2’.26 The aim was to demonstrate the inability of both the South Vietnamese Government and 1ATF to prevent Viet Cong from occupying villages and imposing temporary communist political control over the villagers. This was confirmed by the interrogation of prisoners taken at Xa Hoa Long who stated:

The intention was to overrun the Regional Force Post and hold it for two to three days to demonstrate the ineffectiveness of the Government of Vietnam and 1ATF in preventing Viet Cong incursions into populated areas.27

The result was a political failure and military disaster for both 33 NVA Regiment and C41 Chau Duc District Company.

11 June: A Defended Bunker System - The Third Battle with 33 NVA Regiment

The third battle began at 1445 hrs on 11 June when B company 6RAR-NZ found and attacked 2 Battalion 33 NVA Regiment in a strongly defended bunker system 5000 metres west of FSPB Virginia (Map 3). When patrolling along the axis of a Viet Cong communications route in the western half of AO Vincent, a forward scout from the leading platoon saw a small group of North Vietnamese in bunkers at a distance of forty-five metres, and at ten metres a sentry sheltering from the monsoonal rain under plastic sheeting. The company commander, Major Holland, decided to make a silent platoon attack from a flank, but surprise was lost when the sentry looked up and saw the forward scout. B Company immediately attacked with one platoon and, on penetrating the system, came under heavy fire from more bunkers. The objective was larger than first realised, so at 1700 hrs the company commander reinforced the attack with a second platoon. The enemy reaction was fierce and relentless: B Company was met by an intense volume of small arms fire and rocket-propelled grenades from the front, flanks and snipers in trees.

During a two-hour firefight in failing light and monsoonal rain, Major Holland, though wounded, coordinated a heavy concentration of artillery fire: 7.62 mini-gun fire from US Army Spooky aircraft, flares from a US Army Firefly aircraft, and rocket and machine gun fire from a gunship escort for Dustoff helicopters evacuating the wounded.28

The continued artillery fire and pressure by B Company on the enemy’s bunkers was so aggressive and relentless that soon after dark the North Vietnamese abandoned their defensive position and withdrew northwards, leaving their dead behind and carrying their wounded on litters. When B Company advanced into the bunker system, Major Harris, the new company commander, found it had been occupied by more than 200 North Vietnamese.29

This was a decisive battle. It drove 2 Battalion 33 NVA Regiment out of a secure, well defended, tactical position, forced it into a hasty retreat, and prevented it from providing a secure base for survivors from 1 Battalion 33 NVA Regiment and C41 Chau Duc Company after their failed occupations of Xa Binh Ba and Xa Hoa Long.

12 June: Ambush in the Open - The Fourth Battle with 33 NVA Regiment

The fourth battle was a continuation of the previous night’s attack by B Company on 2 Battalion 33 NVA Regiment’s bunker system (Map 3). It began at 0930 hrs on 12 June when V Company (NZ), deployed in a series of platoon ambush positions, observed a column of more than 200 North Vietnamese moving along a well-used Viet Cong communications route near LZ Soot in the north-west of AO Vincent. They were carrying about twenty-five casualties on litters and holding pieces of green bush over their heads for camouflage. When the column entered the first of the ambushes, Major Lynch, the NZ company commander, called the 6RAR-NZ command post, demanding ‘all available air urgently’, explaining that light fire teams would be better weapons than artillery to use against a long, straggling line of North Vietnamese in the open. The command post immediately ordered three light fire teams for close air support and an airborne observer, Jade, to direct an airstrike.

When a passing Sioux helicopter flew overhead, the enemy column split into two: the rear half fled back along the track and went to ground in thick scrub; the leading half ran forward and found cover in dead ground in a dry creek bed. Surprise was lost. Though the North Vietnamese were more than 300 metres away, V Company engaged them with small arms, machine guns and M79 grenades. During the hour-long firefight, the North Vietnamese regrouped for a counterattack but were forced to retreat under pressure from V Company and from rocket and heavy machine gun fire from helicopters. At 1130 hrs two platoons of V Company attacked the enemy, killing small groups and forcing the survivors to abandon their positions, leaving behind a large amount of equipment scattered over the site. Bodies and documents identified 2 Battalion 33 NVA Regiment supported by at least two heavy weapons companies.30

This was the final contact with 33 NVA Regiment during Operation LAVARACK. Soon afterwards, 547 Signals Troop in Nui Dat intercepted a message from the regimental headquarters rebuking the commander of 2 Battalion for his poor performance on 12 June, saying that he had demonstrated a ‘lack of battlefield discipline in breaking and running in daylight’.31 The survivors from 33 NVA Regiment crossed the northern border of Phuoc Tuy Province and retreated to their home base in Long Khanh Province where, in late June, they were identified by US Army electronic intelligence. 32

5-20 June: 274 VC Regiment in the Bottleneck and Courtenay

The frequency of contacts with elements of 274 VC Regiment demonstrated that it was fully integrated into the communist operational and administrative structure in Phuoc Tuy Province. It operated freely as a matter of routine, using communication routes, staging areas, bunker systems, resupply points, rest areas and medical installations, and made use of ‘home bases’ in Phuoc Tuy Province when there was a need for re-arming and reorganising before and after conducting offensive operations. During Operation LAVARACK, 6RAR-NZ had thirteen contacts with elements of 274 VC Regiment, some with its rifle companies and others with subordinate units such as 2089 Infiltration Unit, C21 Sapper Recce Company, C22 Transport Company, C24 Convalescent Company and C25 Assault Youth Company. On occasions its presence was identified from prisoners, documents, bodies or abandoned equipment. Three of the contacts were decisive battles.

5 June: The Courtenay - First Ambush of 274 VC Regiment

The first major contact occurred on the east-west communications route in the Courtenay at 1930 hrs on 5 June when the headquarters and a platoon of D Company 6RAR-NZ ambushed more than 100 Viet Cong. Because the incoming direction of the enemy was not known, the company commander, Major Stewart, used a triangular shaped ambush which covered all approaches, and sited a series of claymores which would be fired to initiate contact. During stand-to, an enemy column was seen moving in darkness in single file on one side of the ambush position. The sentries allowed the first thirty Viet Cong through and when the main group was in the killing ground a flare was set off and claymores fired. Surviving Viet Cong withdrew to dead ground about twenty metres in front of the ambush position and were engaged by small arms, M79 grenades and artillery. A sweep at first light found six bodies and captured two wounded.

One of the prisoners, Nguyen Van Sung, identified the Viet Cong as a composite group from 274 VC Regiment: C22 Transport Company and 2 Company 2 Battalion; and staff officers from HQ 274 VC Regiment: Ut Thang, a unit commander, and Ba Thanh, a staff officer. The column was moving to Nui May Tao to be resupplied with weapons and ammunition in preparation for an unspecified attack, possibly against FSPB Grey in Long Khan province.33

17 June: The Bottleneck - Attack on 1 Battalion 274 VC Regiment

The second major contact with 274 VC Regiment occurred on 17 June following an ‘aerial radio direction finding’ by 547 Signals Troop in Nui Dat when tracking the movement of HQ 274 VC Regiment from its ‘home base’ in Long Khanh Province towards the Royal Thai Army base at FSPB Grey.34 274 VC Regiment was expected to enter Phuoc Tuy Province on its way to attack FSPB Grey. To disrupt its entry, 6RAR-NZ inserted V Company (NZ) about 3000 metres west of the Bottleneck to conduct a block, search and ambush operation.35

On 17 June V Company contacted elements of 1 Battalion 274 VC Regiment in three separate areas north-west of the Bottleneck. The first battle occurred late in the afternoon when a group of Viet Cong were killed as they entered a platoon ambush site. Four hours later a second and larger group entered the same ambush position and was engaged by a platoon of V Company in darkness at a distance of ten metres. The Viet Cong returned fire, probed the ambush from the flanks and continued attacking in darkness despite close artillery support and 7.62 machine gun fire from Spooky. The platoon held its position until 0200 hrs when all Viet Cong attacks failed and they withdrew.

The second battle occurred nearby at 1630 hrs on a high ridge beside a river when V Company’s lead platoon contacted a lone Viet Cong beside a stream and killed him. When the platoon conducted a sweep of the contact site it came under accurate rocket-propelled grenade and small arms fire from a large group of Viet Cong in bunkers on the other side of a stream. Despite the heavy volume of fire, two platoons of V Company attacked the enemy position. The firefight was intense and continued until last light when the enemy abandoned their bunkers and withdrew.36 Documents and bodies identified 1 Battalion 274 VC Regiment, which was probably using the area as a convenient operational staging point in support of the regimental attack on FSPB Grey.

20 June: The Courtenay - Second Ambush of 274 VC Regiment

The final contact with 274 VC Regiment occurred on 20 June. It was also a consequence of the Viet Cong attack on FSPB Grey on 17 June. The intelligence expectation was that Viet Cong survivors would pass along the secure east-west route through the Bottleneck, Triangle and Courtenay to deliver casualties and be resupplied from the logistics support bases in Nui May Tao. Major Stewart, the company commander of D Company 6RAR-NZ, positioned his platoons in a series of ambushes along this route but was concerned that his platoon-sized ambushes would be opposed by larger sized enemy forces. To neutralise enemy superiority in numbers, he used series of banked claymores as an integral part of D Company’s ambushing tactic.37

Just after first light on 20 June, a platoon of D Company ambushed a large group of Viet Cong from 1 Battalion 274 VC Regiment: C32 Company, C24 Convalescent Company, C12 Assault Youth Company and K21 Sapper Recce Company. The ambush, which had been in position for three days, was sited on the edge of thick bamboo overlooking the well-used Viet Cong pathway in the Courtenay Rubber Plantation. It was about sixty metres long with banks of claymores angled in series along the track. Towards last light more than 100 Viet Cong were seen moving from the Triangle towards Nui May Tao. The leading elements were allowed through the ambush position and when the main body was inside the killing ground the claymores were fired and the area swept with machine gun and small arms fire. Viet Cong survivors scattered to the south and west, some returning fire as they fled. A sweep recovered twenty-two bodies including two officers, a non-commissioned officer, an intelligence clerk and large quantities of weapons, ammunition, litters, medical stores, food and documents. One document was a letter from 1 Battalion 274 VC Regiment, referring its casualties to K76A hospital.

Nearby, a second large group of Viet Cong was seen moving through the same area. Due to an overflight by helicopters from a light fire team, the group scattered and as a result was unidentified, though abandoned litters and equipment indicated they were porters carrying wounded to K76A hospital, and were protected by elements of 274 VC Regiment.38 There were a number of blood trails.

Disruption of the VC Administrative System

An unacknowledged achievement of Operation LAVARACK was that it severely disrupted the Viet Cong administrative system in Phuoc Tuy Province. Before 1969 the 1ATF operational focus was on the Long Hai Hills, Route 44 and operations with United States forces outside Phuoc Tuy Province. The west and north of Phuoc Tuy Province were neglected and became relatively safe for the Viet Cong, who took the opportunity to extend their administrative systems into these areas.

By mid-1969 they had built a series of bunkers for use as staging depots, rest and recovery camps, medical facilities, courier posts, supply points and caches for food, medical supplies, weapons, ammunition and general military equipment. These installations were positioned along Viet Cong routes connected to major storehouses in Nui May Tao, and serviced main force units when they entered Phuoc Tuy Province.39 Three important elements of this administrative system were the east-west communication route across the north of Phuoc Tuy Province, logistics installations inside Phuoc Tuy Province, and the casualty evacuation system.

The East-West Communications Route

The east-west communications route was an active, secure logistics pathway through the Triangle, the Bottleneck and the Courtenay (Map 2).40 Information from casualties, prisoners, documents and equipment identified many support units and installations such as: Post B6, a Viet Cong supply depot at the western entrance to the Bottleneck; C5 Forward Supply Unit from Ba Long Province Rear Services Group; the Baria Provincial Party Chapter, Ba Long Province Forward Supply Council; and the B1 and B2 Cao Xu Postal Units, which operated a mail delivery system from Nui May Tao to forward supply units in Phuoc Tuy, Bien Hoa and Long Khanh Provinces.41

The abandoned village of Xa Cam My was used by the Ba Long Province Forward Supply Council as a central control point for their administrative system. One of its storage bunkers held a large supply of food—rice, peas, salt, gelatine, flour, maize, dried fruit, soya bean oil and tinned fish—and recently had issued forty-four short tons of rice, sufficient for 1800 Viet Cong for one month.42

C195 Company was a Viet Cong ‘Special Delivery Unit’ from Military Region T7. Its ‘supply’ task was the delivery of military equipment, weapons, ammunition, general stores, food and clothing; its ‘operational’ tasks were reconnaissance, porterage, battlefield recovery and casualty evacuation. During Operation LAVARACK, 6RAR-NZ identified the frequent involvement of C195 Company in contacts: in a bunker system on the east-west communications route north of LZ Ash;43 from the body of ‘squad leader of C195 Company’ at the western entrance to the Bottleneck;44 in K76B hospital bunkers 2000 metres south of LZ Ash; at Xa Binh Ba with 33 NVA Regiment on 6 June, when twelve were killed and eleven wounded; and in late June with 67 Engineer Battalion conducting a reconnaissance of Regional Force Post Phu My 5 in preparation for an attack by 274 VC Regiment.45

Successful contacts by 6RAR-NZ during Operation LAVARACK inflicted many casualties on C195 Company, reducing its effectiveness in both its administrative and operational roles, and severely damaging its ability to service main force units.

Bunker Systems

Bunker systems in Phuoc Tuy Province were an important part of the Viet Cong administrative system (Map 5). Some were for accommodation, others for storage. Accommodation bunkers were built above ground and designed for protection from artillery fire and bombing.46 They usually covered large areas such as the C41 Chau Duc District Company’s ‘home base’ of nineteen large bunkers spread over an area 120 by 150 metres and occupied by over forty Viet Cong,47 and a system captured by B Company which was occupied by more than 200 North Vietnamese from

Map 5. Attack Routes at Binh Ba

2 Battalion 33 NVA Regiment.48 Storage bunkers usually had shelving and contained caches of ammunition, weapons, documents, maps, clothing, food and general stores. A storage bunker captured in the Bottleneck contained plastic explosive, Bangalore torpedoes, grenades, anti-tank mines and mortar bombs; and another in the Courtenay was an ammunition point holding a large quantity of grenades, anti-tank mines, plastic explosive, mortar bombs and 75mm recoilless rifle rockets. Bunkers were the basis of the Viet Cong distribution system and their destruction during Operation LAVARACK was a severe setback for Viet Cong administration.

Hospitals

The main hospital for Military Region T7 was K76A in Nui May Tao. It accepted casualties from main force units in Phuoc Tuy, Long Khanh, Bien Hoa and Binh Tuy Provinces. During Operation LAVARACK, 6RAR-NZ uncovered a second major hospital in the west of Phuoc Tuy Province. On 22 June, W Company (NZ) entered a bunker system on a Viet Cong route about 2000 metres south of LZ Soot and came under heavy fire from small arms, machine guns and rocket-propelled grenades. After a fierce firefight, Major Williams, the company commander, called for artillery support, a light fire team and an airstrike. By 1310 hrs the Viet Cong had been driven out of the bunkers. On entering the system, W Company found thirty-one bunkers, an operating theatre, two wards and a number of fighting pits sited for all-round defence; and recovered large quantities of food, clothing, military equipment, grenades, bottles of plasma, medicines, drugs, hospital instruments and medical appliances. Captured documents identified K76B hospital, a medical installation for casualties from 33 NVA Regiment, 274 and 275 VC Regiments and D440 LF Battalion.49 An associated medical facility, K10 dispensary, was found by B Company in a large bunker system 2000 metres south of K76B hospital.50 These attacks on bunker systems during Operation LAVARACK destroyed the ability of K76B hospital and K10 dispensary to function, and forced both medical facilities to withdraw to K76A hospital in Nui May Tao.51

Viet Cong Casuality Evacuation System

In June 1969, radio direction-finding operators in 547 Signals Troop in Nui Dat tracked the movement of 274 VC Regiment from its base in Long Khanh Province towards Bien Hoa City, and decoded a message from the regiment’s commander to 84 Rear Services Group: ‘...after contact you are to take wounded to Nui May Tao as discussed at the meeting’.52 This signals intelligence information was passed to FSPB Grey, where a strong defence inflicted a large number of casualties on 274 VC Regiment. The Viet Cong plan was to evacuate the wounded by porter parties to casualty-collecting stations in the Bottleneck and then to K76A hospital.

At 0710 hrs on 20 June, a D Company platoon ambushed over 100 Viet Cong porters and armed escorts, capturing a porter, Khuat Duy Don.

Khuat Duy Don, age 21, was an infiltrator from North Vietnam. During interrogation he confirmed that stretcher-bearers conducted a casualty evacuation system through the Courtenay Rubber Plantation to hospitals in Nui May Tao. With seven others he was led to Phuoc Tuy Province by guides. His unit was 2089 Mobile Company. He arrived in a base camp on 13 June 1969 with his platoon of twelve, and on the afternoon of 19 June, a group of ninety Viet Cong joined them. They carried light machine guns and AK47s. On the evening of 19 June he was issued with eight litres of rice. At 0450 hrs on 20 June, his group moved through a rubber plantation across two roads and at first light arrived at an RV where they collected wounded Viet Cong. With five of his party to each wounded on a litter they moved east, but at 0700 hrs they were ambushed. He dropped his litter and with eleven others fled north.53

During the sweep, a second large group of Viet Cong was identified moving through the same area; abandoned litters and equipment indicated that they were also porters carrying wounded to K76A hospital.54

Effect on Viet Cong Morale

Successful ambushing along the east-west route during Operation LAVARACK denied the Viet Cong safe use of a previously secure casualty evacuation route, and added to the general disruption of Viet Cong administration. The subsequent decline in support for operational units in Phuoc Tuy Province affected morale and efficiency. Le Van Khanh, a platoon commander in 33 NVA Regiment,55 told interrogators:

Life was very difficult with the Viet Cong, morale was very low and most of the battalion wanted to surrender but did not know how. Food was scarce and supply of rice was difficult because of Australian activity, so carriers were sent on a three day march [to Xa Thai Thien on National Route 15] each way for food. Rations were very short and mainly consisted of dry cod and noodles; ammunition for 33 NVA Regiment’s mortars was very short with only about twenty rounds for each mortar; and small arms ammunition was available but had to be picked up from the Cambodian border.56

Documents recovered from K76B hospital recorded that the wards were in poor condition, staff morale was low and patients complained of scarcity of medical drugs, poor quality of medicines, unsatisfactory treatment and military operations that were ‘causing difficulties in obtaining food.57 One Viet Cong diarist wrote that he was eating ‘plant shoots and fern roots’. Khuat Duy Don a stretcher-bearer in 2089 Mobile Company said, ‘his unit was short of food and he often had to eat just rice and vegetables’, and he was ‘not happy as a soldier’.58

Constant pressure by 6RAR-NZ on the Viet Cong administrative system during Operation LAVARACK had been effective. There were eighty-five contacts between 6RAR-NZ and Viet Cong groups, and of these more than thirty-four occurred along the east-west route. They brought normal Viet Cong administrative traffic to a halt and severely weakened the ability of rear service groups to supply Viet Cong units. The resultant ineffective administration contributed to a strategic redeployment of Viet Cong main force units: the survivors of 33 NVA Regiment retreated to a ‘home base’ in the Ong Que Rubber Plantation in Long Khanh Province;59 the second main force unit, 274 VC Regiment, was dispersed into safe ‘home bases’ in Long Khanh and Bien Hoa Provinces;60 84 Rear Services Group, due to operational inefficiencies and a shortage of food, was moved out of Military Region T7 and sent north to War Zone D;61 and in early July, HQ 5 VC Division (which commanded 33 NVA Regiment and 274 and 275 VC Regiments) withdrew from Military Region T7 ‘because of lack of food and supply difficulties’ and moved north into War Zone D.62

Conclusion

A major contribution to these military successes was the ‘spectacularly effective’63 tactical positioning of the five rifle companies on all enemy routes throughout western and northern Phuoc Tuy Province. Though this broad spread of rifle companies minimised mutual support, it resulted in an unusually large number of contacts with Viet Cong, and demonstrated that the advantages of a numerically superior enemy over isolated rifle companies could be neutralised by effective, timely fire support.

Operation LAVARACK was a unique military success. During thirty-two days of continuous patrolling and ambushing, results were remarkable: the defeat in battle of two main force regiments and a district company with crippling losses; the capture and destruction of hundreds of enemy bunkers; the disruption of the Viet Cong administrative system in Phuoc Tuy Province; the denial to the enemy of vital lines of communication and supply; and the irreparable reduction of the military and political position of the Viet Cong in Phuoc Tuy Province. The outcomes of Operation LAVARACK were so strikingly exceptional that they are deserving of serious historical recognition.

Endnotes

1 Ashley Ekins, Head, Military History Section, at ‘A symposium to commemorate the 40th anniversary of the Battle of Binh Ba, South Vietnam, 6–8 June 1969’

2 This summary does not include enemy casualties at Xa Binh Ba on 6 June.

3 6RAR-NZ (Anzac) Battalion was a combined Australian and New Zealand battalion; there were three Australian rifle companies (A, B and D) and two New Zealand (V and W), and additional New Zealand headquarters and support company personnel. 6RAR-NZ was supported by B Squadron 3 Cavalry Regiment, B Squadron 1 Armoured Regiment, 101 Field Battery RAA, 1 Field Squadron RAE and 161 Reconnaissance Flight.

4 War Diary HQ 1ATF, 1-4-151, op instr 49/69 (op Lavarack), 29 May 1969, pp. 175–81; and War Diary 6RAR, 7-6-17, opo 1 (op Lavarack), 29 May 1969, pp. 89–114.

5 During June the two other battalions in 1ATF, 5RAR and 9RAR conducted operations in AO Illawarra, in the Nui Thi Vai Hills to the south of AO Vincent, and AO Aldgate and AO Block in the Long Hai Hills, Route 44 and Dat Do to the south-east.

6 For efficiency of command and control, COSVN—the Central Office for South Vietnam (Viet Cong)—divided South Vietnam into military regions. Phuoc Tuy Province was in Military Region T7. See L Johnson (ed.), The History of 6RAR-NZ (ANZAC) Battalion, Volume Two, 1967 to 1970, 6 RAR/NZ Bn, Enoggera, 1972, pp. 39–42, and the pocket enclosed map, ‘Enemy Districts, Base Areas and Units’.

7 COSVN divided South Vietnam into Viet Cong provinces. Ba Long Province included all Phuoc Tuy and parts of Bien Hoa, Long Khanh and Binh Tuy Provinces. See Johnson, The History of 6RAR-NZ (ANZAC) Battalion, pp. 40–42, and the pocket enclosed map, ‘Enemy Districts, Base Areas and Units’.

8 For detailed descriptions of the storehouses and K76A hospital in Nui May Tao, see Johnson, The History of 6RAR-NZ (Anzac) Battalion, pp. 95–109.

9 War Diary HQ 1ATF, 1-4-156, Vietnam digest 19/69, 24–31 May 1969, pp. 165–168; War Diary HQ 1ATF, 1-4-151, op instr 49/69 (op Lavarack), 29 May 1969, p. 181; War Diary 6RAR, 7-6-17, opo 1 (op Lavarack), 29 May 1969, p. 106; Johnson, The History of 6RAR-NZ (ANZAC) Battalion, pp. 39–42, 47–48, 51–53.

10 D M Butler, Interview with author, 1 December 1969.

11 A Bishop, Interview with author, 20 June 2009.

12 War Diary HQ 1ATF, 1-4-156, Vietnam digest 19/69, 24–31 May 1969, paras 11–12, p. 2, assessment of enemy intentions, p. 167; Vietnam Digest 20/69, 17–24 May, para 8–9, p. 3, assessment of enemy intentions, p. 172; Vietnam digest 23/69, 7–14 June 1969, paras 8–11, p. 3, assessment of enemy intentions, p. 186; War Diary HQ 1ATF, 1-4-156, enemy situation, 1–8 June 1969, paras 2e and 2g, p. 157.

13 Proselytisers from the Ba Long Province Proselytising Unit accompanied 1 Battalion 33 NVA Regiment into Binh Ba and began instructing villagers on arrival. War Diary HQ 1ATF, 1-4-156, intsum 160/69, 9 June 1969, p. 106.

14 A57 Rear Services Company was attached to 1 Battalion 33 NVA Regiment. It was probably on a resupply mission because captured documents included an indent for rice from C5 Company 84 Rear Services Group in Nui May Tao.

15 A light fire team consisted of two helicopter gunships and a heavy fire team three. 9 Squadron RAAF named their gunships Bushrangers.

16 War Diary 6RAR, 7-6-18, ops log, 5 June 1969, sheets 3–15, pp. 48–61; 6RAR War Diary, 7-6-22, contact after action report (W Company NZ), 5 June 1969, pp. 145–47; Johnson, The History of 6RAR-NZ (ANZAC) Battalion, p. 48; Brian Avery, We Too Were Anzacs, Slouch Hat Publications, Rosebud, 2004, pp. 97–98.

17 A H Smith, Interview with author, 27 November 2008.

18 War Diary HQ 1ATF, 1-4-156, ground commanders daily situation report, 6 June 1969, paras 1a(6–7), p. 15; D M Butler, Interview with author, 28 October 2009. The decision to deploy the ready reaction force was made during two radio discussions between the commanders of 1ATF and 6RAR-NZ at 0815 and 0820 hrs on 6 June 1969.

19 The ready reaction force consisted of D Company 5RAR, a composite troop from B Squadron 1 Armoured Regiment and 3 Troop B Squadron 3 Cavalry Regiment, supported by 105 Field Battery RAA. The 6RAR-NZ command post in FSPB Virginia expected the ready reaction force to join the 6RAR-NZ command net as another sub-unit under command for orders, coordination of fire support from artillery, mortars and offensive air, and for casualty evacuation and reporting.

20 A H Smith, Interview with author, 27 November 2008; War Diary, B Squadron 1 Armoured Regiment, 2-2-5, ops log, 1–30 June 1969; War Diary 1ATF, 1-4-153, ops log, 5–6 June 1969, sheets 37–43, pp. 49–55; War Diary 6RAR, 7-6-18, ops log, 6 June 1969, serials 7–62, pp. 62–67; A Perriman, ‘The Battle of Binh Ba’, Australian Infantry, September 1969, pp. 5–7.

21 At this stage the enemy casualties caused by the tank troop were: ‘27 KIA and 2 PW’; A H Smith, Interview with author, 27 November 2008; War Diary, B Squadron 1 Armoured Regiment, 2-2-5, ops log, 6 June 1969; ‘Heritage, The Battle at Binh Ba, Operation Hammer, South Vietnam 6–8 June 1969’, Ironsides, The Magazine of the Royal Australian Armoured Corps, Combat Arms No. 2, 1983, pp. 3–10.

22 War Diary HQ 1ATF, 1-4-153, ops log, 6 June 1969, sheets 38–42, pp. 52–56; and War Diary 6RAR, 7-6-18, ops log, 6 June 1969, pp. 62–68.

23 War Diary 5RAR, 7-5-27, combat after action report 6/69 (op Hammer), 11 June 1969, pp. 84–92.

24 War Diary 6RAR, 7-6-22, contact after action report (A Company), 4 June 1969, pp. 7–9.

25 War Diary HQ 1ATF, 1-4-156, enemy situation in Phuoc Tuy Province, 1–8 June 1969, pp. 157–58; C H Ducker, Officer Commanding C Company 5RAR during Operation TONG in June 1969, Interview with author, 25 November 2008; War Diary 5RAR, 7-5-27, contact after action report 8/69, Operation TONG, 7 June 1969.

26 War Diary 5RAR, 7-5-27, combat after action report 6/69 (op Hammer), Annex A, para 6b, 11 June 1969, p. 89; War Diary 6RAR, 7-6-22, after action report, para 4a(1)(b), 1–30 June 1969, p. 165; War Diary HQ 1ATF, 1-4-156, Vietnam digest 19/69, 24–31 May 1969, paras 11–12, p. 2, assessment of enemy intentions, p. 167; Vietnam Digest 20/69, 17–24 May, para 8–9, p. 3, assessment of enemy intentions, p. 172; Vietnam digest 23/69, 7–14 June 1969, paras 8–11, p. 3, assessment of enemy intentions, p. 186; War Diary HQ 1ATF, 1-4-156, enemy situation, 1–8 June 1969, paras 2e and 2g, p. 157.

27 Interrogation of prisoners at Xa Hoa Long on 7 June; War Diary HQ 1ATF, 1-4-156, enemy situation, 1–8 June 1969, para 2g, p. 157.

28 Spooky, or Puff the Magic Dragon, was a C47 Douglas DC3 with flares and three Gatling mini-guns each of eighteen barrels. Firefly was a C130 with lights and cluster flares. Dustoffs were Iroquois helicopters with an onboard medical crew for casualty evacuation.

29 War Diary 6RAR, 7-6-22, contact after action report (B Company), 11 June 1969, pp. 28–30; War Diary HQ 1ATF, 1-4-154, ops log, sheets 87–90, June 69, pp. 19–22; Johnson, The History of 6RAR-NZ (ANZAC) Battalion, p. 49; Avery, We Too Were Anzacs, pp. 98–99.

30 War Diary 6RAR, 7-6-18, ops logs, 12 June 1969, pp. 104–07; War Diary 6RAR, 7-6-22, contact after action report (V Company NZ), 12 June 1969, pp. 74–77; War Diary HQ 1ATF, 1-4-154, ops log, 12 June 1969, sheets 90–93, pp. 22–25; Johnson, The History of 6RAR-NZ (ANZAC) Battalion, pp. 49–51; Avery, We Too Were Anzacs, pp. 106–07.

31 D M Butler, Interview with author, August 2009.

32 War Diary HQ 1ATF, 1-4-160, Vietnam digest, issue 25/69, 21–28 June 1969, para 7, p. 178.

33 War Diary HQ 1ATF, 1-4-156, intsum 158/69, 7 June 1969, para 7, p. 102; War Diary 6RAR, 7-6-22, after action report 1-30 June 1969, pp. 94–95; War Diary 6RAR, 7-6-18, ops log, 5–6 June 1969, pp. 60–63; War Diary HQ 1ATF, 1-4-153, ops log, 5–6 June 1969, sheets 37–39, pp. 49–53; Johnson, The History of 6RAR-NZ (ANZAC) Battalion, p. 51; Avery, We Too Were Anzacs, pp. 98–99.

34 FSPB Grey was about twenty kilometres west of Xuan Loc city in Long Khanh Province. In June 1969 FSPB Grey was occupied and defended by the Royal Thai Army.

35 A Bishop, Interview with author, 20 June 2009; War Diary 6RAR, 7-6-20, operation order, 16 June 1969, p. 67.

36 War Diary 6RAR, 7-6-18, ops log, 17 June 1969, pp. 106–08; War Diary 6RAR, 7-6-22, contact after action report (V Company NZ), 17 June 1969, pp. 78–85; War Diary 6RAR, 7-6-22, after action report 1–30 June 1969, pp. 165–67; Avery, We Too Were Anzacs, p. 109.

37 I Stewart, AWM, oral history recording, 2 May 1996.

38 War Diary 6RAR, 7-6-19, ops log, 20 June 1969, serials 1–32, sheets 1–6, pp. 44–49; War Diary 6RAR, 7-6-22, after action report 1–30 June 1969, pp. 94–95; War Diary HQ 1ATF, 1-4-154, ops log, 20 June 1969, pp. 78–82; War Diary 6RAR, 7-6-22, contact after action report (D Company), 20 June 1969, pp. 103–05; War Diary HQ 1ATF, 1-4-156, intsum 171/69, 20 June 1969, para 3a, p. 130; A Bishop, Interview with author, 20 June 2009.

39 War Diary 6RAR, 7-6-22, after action report, intelligence summary, 1–30 June 1969, pp. 165–67.

40 War Diary 6RAR, 7-6-17, enemy situation, opo 1 (op Lavarack), 29 May 1969, pp. 106–07; War Diary 6RAR, 7-6-22, after action report, 1–30 June 1969, pp. 165–80; Johnson, The History of 6RAR-NZ (ANZAC) Battalion, p. 50, and the pocket enclosed map, ‘Operation Lavarack enemy situation’.

41 War Diary 6RAR, 7-6-22, after action report, para 4b(1)(d), 1–30 June 1969, p. 165; War Diary HQ 1ATF, 1-4-156, intsum 155/69, para 7, 1–30 June 1969, p. 93.

42 The rice had been provided by suppliers in Dat Do and Provincial Route 44 villages. War Diary HQ 1ATF, 1-4-156, intsum 162/69, para 7, 11 June 1969, p. 111. Xa Cam My was on Provincial Route 2 north of the large village of Xa Binh Gia. B Squadron 1 Armoured Regiment on operations near Xa Binh Gia and Xa Cam My found a plantation of maize being tended by a Viet Cong man with a rifle. When challenged he fired one shot and fled. On harvesting the crop, the Duc Thanh Regional Force Company recovered eight 5-ton truck loads of maize cobs. A H Smith, Interview with author, 28 June 2009.

43 War Diary HQ 1ATF, 1-4-156, intsum 157/69 para 7, 6 June 1969, p. 98. In this contact C195 Company was (mistakenly) identified in the intelligence summary as a ‘Postal Unit subordinate to HQ MRT7’.

44 War Diary HQ 1ATF, 1-4-156, intsum 158/69 para 7, 7 June 1969, p. 102.

45 War Diary HQ 1ATF, 1-4-160, intsum 195/69 para 12e(2), 14 July 1969, p.120.

46 M J Harris, Interview with author, 16 October 2009. Usually Viet Cong did not sleep in bunkers but in hammocks outside. Weapon pits or ‘special bunkers’ were tactically sited on likely approaches.

47 War Diary 6RAR, 7-6-22, contact after action report (A Company), pp. 7–9, 4 June 1969, p. 166.

48 War Diary 6RAR, 7-6-18, ops logs, 5 June 1969, pp. 98–102; War Diary 6RAR, 7-6-22, contact after action report (B Company), 11 June 1969, pp. 28–30; Johnson, The History of 6RAR-NZ (ANZAC) Battalion, p. 49; Avery, We Too Were Anzacs, pp. 98–99.

49 War Diary 6RAR, 7-6-22, after action report, para 4b(1)(c) and 4b(2), 1–30 June 1969, p. 167; War Diary HQ 1ATF, 1-4-154, ops log, sheet 171, p. 103.

50 Documents recovered from the body of Cao Van Tich, the ‘political officer of K10’, confirmed its identification; War Diary HQ 1ATF, 1-4-156, intsum 176/69, para 7, 25 June 1969, pp. 143–44.

51 War Diary HQ 1ATF, 1-4-156, intsum 158/69, para 7, 7 June 1969, p. 102, and intsum 160/69, June 1969, p. 106; War Diary 6RAR, 7-6-22, after action report, para 4b(1)(c) and 4b(2), 1–30 June 1969, p. 167.

52 A Bishop, Interview with author, 20 June 2009.

53 War Diary HQ 1ATF, 1-4-156, intsum 174/69, para 4, 23 June 1969, pp. 138–39, interrogation Khuat Duy Don.

54 War Diary 6RAR, 7-6-19, ops log, 20 June 1969, serials 1–32, sheets 1–6, pp. 44–49; War Diary 6RAR, 7-6-22, contact after action report (D Company), 20 June 1969, pp. 103–05; War Diary HQ 1ATF, 1-4-154, ops logs, sheets 146-150, 20 June 1969, pp. 78–82.

55 Le Van Khanh was the platoon commander of 8 platoon 8 heavy weapons company, D440 LF Battalion and was attached to C2 heavy weapons company 33 NVA Regiment for the occupation of Xa Binh Ba.

56 War Diary HQ 1ATF, 1-4-160, intsum 198/69, 17 July 1969, pp. 212–13, interrogation Le Van Khanh.

57 War Diary HQ 1ATF, 1-4-156, intsum 176/69, 25 June 1969, pp. 143–44, documents captured at K76B hospital.

58 War Diary HQ 1ATF, 1-4-156, intsum 174/69, 23 June 1969, pp. 138–39, interrogation Khuat Duy Don.

59 War Diary HQ 1ATF, 1-4-160, Vietnam digest, 25/29, 21–28 June 1969, pp. 177–79.

60 In July 1969, HQ 274 VC Regiment returned to Phuoc Tuy Province to a ‘freshly renovated base camp’ north of the Nui Thi Vai Hills; War Diary HQ 1ATF, 1-4-160, Vietnam digest 26/29, para 7, 28 June to 5 July 1969, p. 184.

61 The Xuan Loc Worksite, C125 Transport Company, K76A and K1500 Hospitals, and Z300 Workshop remained in place in Nui May Tao.

62 War Diary HQ 1ATF, 1-4-160, Vietnam digest 26/29, paras 6 and 13, 28 June to 5 July 1969, pp. 184, 186.

63 Ashley Ekins, Head, Military History Section, at ‘A symposium to commemorate the 40th anniversary of the Battle of Binh Ba, South Vietnam, 6–8 June 1969’.