Abstract

It is recognised that the application of simulation is a key enabler in enhancing the effectiveness and efficiency in the conduct of training, and supports the adaptation required to maximise performance on operations. The development of the mission specific training program has witnessed the use of live, virtual/hybrid and constructive simulations within a single training activity. The aim of this article is to define the mission specific training concept and discuss its evolution and methodology, which includes the application of deliberate practice. The article will then discuss the rationale behind its development, its associated benefits and the way ahead.

Introduction

The ‘Adaptive Army’ restructure constitutes the most significant change to the Australian Army since the implementation of the Hassett reforms in 1973. Adaptive Army aims to change the Army’s approach to and conduct of its core business, seeking to effect profound reform in training, personnel management, knowledge management, learning cycles and, eventually, the culture of the Army.

The key feature of the Adaptive Army restructure was the raising of the Land Combat Readiness Centre (LCRC) in December 2008. The LCRC’s aim is to realise the 1st Divisions force preparation vision of leading edge, mission ready land forces’. The LCRC is destined to become the Army’s centre of excellence in preparing forces for deployment while also assuming responsibility for supporting post-deployment reintegration into Forces Command.

The LCRC’s role is to provide practised, ready and certified forces for operations and contingencies. The centre also conducts warfighting training to support achievement of Army mission essential task requirements. In addition, the LCRC supports Commander 1 Division by coordinating higher level training and assessment in order to raise training standards across the Army. The centre aims to standardise procedures for the mounting, assessment, certification and demounting of force elements so as to maximise the Army’s success in current and future operations. This will inevitably lead to further efficiencies in the way the Army employs its resources.

The Combat Training Centre is an integral element of the LCRC. Throughout 2009 the Combat Training Centre was primarily responsible for the conduct of mission rehearsal exercises, while Army Simulation Wing provided the opportunity for units to undertake mission specific training (MST) as a precursor to mission rehearsal exercises. Towards the end of 2009, following a review of the Army Simulation Wing MST program by Commander Land Warfare Development Centre, responsibility for this training was transferred to the LCRC. The transfer was formalised in a Commander’s Directive issued in mid-December 2009, with transition scheduled to occur during 2010.1 The transfer of responsibility for simulation support for all pre-deployment training activities from LCRC to Army Simulation Wing will also be examined as part of the LCRC establishment review scheduled for the second half of 2010. Army Simulation Wing currently supports a number of pre-deployment training activities under the direction of the Combat Training Centre.

This article will describe the origins of the former Army Simulation Wing MST program, what the program delivered, and how this training capability will be integrated into the LCRC force preparation continuum, otherwise known as the ‘Road to War’.

What is MST?

On 17 February 2005 the Australian Government decided to deploy additional Australian troops to Iraq, raising the force known as the Al Muthanna Task Group (AMTG1). The AMTG1 was based on Headquarters 2 Cavalry Regiment, a cavalry squadron and a mechanised infantry company from 5/7 RAR, all located in Darwin. The Combat Training Centre was tasked with assisting 1 Brigade in the conduct of a mission rehearsal exercise for AMTG1, scheduled for the early part of April 2005 prior to its deployment to Iraq. The Hamel Battle Simulation Centre in Robertson Barracks was directed to provide suitable simulation to support the training that underpinned the mission rehearsal exercise.

In concert with the Combat Training Centre’s Battle Command Wing, Army Simulation Wing provided a commercial off-the-shelf simulation known as Steel Beasts Two (SB2) to meet this training requirement at the Battle Simulation Centre. The simulation was used to familiarise AMTG1 soldiers with the area of operations, provide troop-level tactical training, and assist Commander AMTG1 and his headquarters staff in their operational planning. An additional off-the-shelf simulation, Virtual Battle Space One (VBS1), was also deployed to add combined arms elements largely absent from SB2, which is vehicle-centric.

The Battle Simulation Centre supported this pre-deployment training, allowing soldiers, particularly tactical level commanders, to be exposed to the simulation systems. Anecdotal reports from soldiers suggest that they benefitted from exposure to simulation; likewise Commander AMTG1 also recognised the value of simulation in providing his soldiers an accelerated force preparation.

The inclusion of a ‘virtual’ games-based simulation training package as part of the Combat Training Centre mission rehearsal exercise for AMTG1 was a another key step in the exploitation of simulation within the Army. The provision of training for AMTG1 provided the impetus for the opening of the Land Command Battle Laboratory in 2005, which subsequently evolved into the Combined Arms Tactical Trainer within the Combat Training Centre.

The Combined Arms Tactical Trainer often provided the first opportunity for units to be exposed to simulation-based training at the collective level in a mission specific environment. The ‘whole of exercise’ support model was employed using current operational experiences and designed by exercise planners familiar with the operational environment. This was an effective mechanism for training that provided sound preparation for units prior to their participation in mission rehearsal exercises. In 2007, the Combat Training Centre relinquished responsibility for the Combined Arms Tactical Trainer to Army Simulation Wing for the purposes of conducting pre-mission rehearsal exercise training. This led to the development of the MST program.

In 2008, Army Simulation Wing undertook a six-month ‘proof of concept’ pilot for its support to MST. The pilot was initiated to support Reconstruction Task Force 4 field training at Wide Bay Training Area over a period of five days. The Army Simulation Wing team provided three platoon-level simulation rotations using Virtual Battle Space Two (VBS2). Each rotation involved the receipt and issue of orders by the platoon commander and the conduct of battle procedure, followed by the execution of simulated platoon-level tactics, techniques and procedures in response to improvised explosive device, ambush, and other simulated activities over a 24 to 36-hour period. An after-action report followed the completion of each platoon rotation, covering the full spectrum of learning from orders preparation, delivery and conduct of tasks. Other support tasks saw the pilot program supporting force preparation for deployments to Afghanistan, the Middle East and the Solomon Islands.

Following the successful conduct of this pilot, additional operational funding was secured to initiate a rolling MST program available to units over a three-year period. In late 2008 and early 2009 a series of unit liaison visits and planning conferences established MST programs to support selected operational deployments occurring throughout 2009. During that year, support was provided to units deploying to Afghanistan, Iraq, East Timor and the Solomon Islands. Scenarios were designed based on the experiences of those recently returned from operational theatres, and from data collated by the Centre for Army Lessons. The scenarios were flexible and adjusted to meet the unit commanders’ training requirements and applicable directed mission essential task lists. By the end of the year Army Simulation Wing had supported over thirty discrete training activities, each lasting around a week.

While foundation warfighting training involves preparation for an unspecified conflict, MST as defined during the course of the program was unit-led training for a defined conflict. MST itself is defined as,

the training for directed tasks that delivers the particular knowledge, skills and attitudes to prepare the individual, team, or task force to deploy on operations in a specific theatre, role or environment. The content of MST is driven by the mission, environment and threat.2

Simulation support to MST was developed by Army Simulation Wing to provide a flexible capability to unit commanders as part of the force preparation cycle. The MST program is principally a technology-based, contractor-supported, unit-led preparation for attendance at a mission rehearsal exercise conducted by the Combat Training Centre. MST is a component of the initial concentration period for units deploying on operations, and focuses on the practice of techniques, procedures and drills prior to the mission rehearsal exercise. MST activity development and execution is often a collaborative arrangement between Army Simulation Wing and the unit, the level and type of training ultimately developed and delivered at the unit commander’s discretion and tailored to meet unit training requirements. Consequently the focus, level and type of MST varies between units. Its delivery also occurs primarily in the respective battle simulation centres of each brigade and uses other training facilities as dictated by the activity.

A key aspect of MST activity design is the application, where practicable, of ‘deliberate practice’. The concept of deliberate practice has emerged from the work of cognitive psychologists who determined that the best performers achieved their success through a combination of both deliberate and reflective practice.3 Practice is generally accepted as a necessary part of the acquisition of expertise. Exceptional or expert performance typically results from extended periods of intense preparation and training or ‘deliberate practice’:

Deliberate practice occurs when individuals, who are highly motivated to develop a skill, engage in a carefully sequenced set of structured practice activities aimed at developing a target skill. Optimal learning takes place when a student performs a well-defined task, at an appropriate level of difficultly. The student then receives informative feedback, and is given opportunities for repetition to correct errors and polish the skill before moving to the next task.4

Deliberate practice therefore promotes adaptive thinking based on the premise that practising some skills may ‘free cognitive resources for higher level decisionmaking’.5 Some key characteristics of deliberate practice as applied to MST are described in Table 1.

What the Program Delivered

The MST program developed throughout 2009 featured activity design based on deliberate practice with repetition in either a lane-based approach or a command post exercise. The basic MST activity was usually lane-based with a linkage between virtual and live lane activities. Training supported by simulation is applied in vignette-style lane-based scenarios or supporting command post exercises. All training is conducted by the unit against the achievement of training objectives through the deliberate practice of techniques, procedures and drills.

Table 1. Deliberate practice characteristics applied to MST

| Character | Description |

| Repetition |

Task performance occurs repetitively rather than at its naturally occurring frequency. MST provides the opportunity to practise procedures, techniques and drills. |

| Focused feedback |

Task performance is facilitated by the coach and learner during performance. MST includes focused feedback sessions during the activity and formal after-action reviews at its conclusion. |

| Immediacy of performance |

After corrective feedback on task performance there is immediate repetition so that the task can be performed in accordance with expected norms. MST activity conduct allows repetition as required. Virtual training activities also allow training scenarios to be quickly reset and hence allow the trainees more exposure. |

| Emphasis on difficult aspects |

Deliberate practice will focus on more difficult aspects. MST is dictated by the training objectives determined by the unit commander. Simulation allows us to replicate the difficult aspects (e.g. air support) that cannot be achieved in traditional ‘live only’ training. |

| Focus on areas of weakness |

Deliberate practice can be tailored to the individual and focused on areas of weakness. In MST this is dictated by the training objectives determined by the unit commander. Live and virtual ‘lanes’ can target specific areas of weakness. |

| Active coaching |

Typically, a coach must be very active during deliberate practice, monitoring performance, assessing adequacy, and controlling the structure of training. Observer trainers or mentors are employed during MST. |

Training lanes are provided up to platoon/troop level and can include the employment of attachments configured for operations such as a section of armoured vehicles. The complexity of lanes depends on the training objectives and level of training. The lanes can be conducted both in a virtual environment using gaming simulations such as the Virtual Battlespace Simulation, and the live environment using the Tactical Engagement Simulation System and aids for simulated battlefield effects.

Virtual lane training is an activity designed to train individual soldiers and small teams in various techniques, drills and procedures used on operations. Training is conducted in the battle simulation centre with computer-aided simulation such as Virtual Battlespace Simulation or Steel Beasts Professional. These simulations can introduce soldiers to scenarios and the use of equipment not normally available in a field setting including armoured vehicles and helicopters.

While virtual training has its benefits, it is usually only employed in scenarios that cannot be replicated in a live environment. By using virtual simulations as a precursor to live training, leaders can train for more complex events often neglected due to resource limitations. A virtual training environment that allows units to exercise and refine standard operating procedures, rehearse reporting procedures and ground tactical movement can save unit commanders valuable resources that are typically expended during the first thirty-six hours in the field when sections and platoons are preparing to conduct training.

Under the MST delivery model, up to two virtual lane training activities are conducted at platoon/troop level or below. Each training activity lasts five days and can be conducted as a precursor to live lane training. Live lane training, usually conducted in the field utilising the Tactical Engagement Simulation System, is designed to train individual soldiers and small teams in various techniques, drills and procedures to be used on operations. Subject to the availability of equipment, the activity can involve the use of armoured vehicles including the ASLAV and Bushmaster, and may also include battlefield effects to simulate mines and indirect fire.

The MST program involves the conduct of up to two live lane training activities at platoon/troop level or below over a five-day period. This training can be conducted in conjunction with virtual lane training.

Collective and staff training is undertaken primarily through the conduct of command post exercises. A command post exercise is an activity primarily designed to train headquarters staff. Ideally, this training should closely replicate the operational environment, be it an office, tent or command vehicle. Command post exercises can be supported by either ‘constructive’ simulations such as the Australian Brigade and Battle Simulation (known as AB2S) or scripted events through a master event list. The conduct of a command post exercise includes the establishment of an exercise control to ensure training is executed as planned and that training objectives are achieved. Where practical, command posts are constructed within the battle simulation centres or other training locations to replicate both the layout and the command and control systems used in theatre. The training is structured to allow the repetition of events so that standard operating procedures can be practised until perfected. A military appreciation process exercise can also be conducted as a staff training activity and would normally precede the conduct of a command post exercise. Both activities are supported through the use of observer trainers and mentors for commanders and their staff.

Under the MST delivery model, up to two command post exercise activities are conducted at battle group and/or combat team level. Each command post exercise is conducted over a five-day period. A military appreciation exercise for key battle group staff may be included in lieu of one command post exercise.

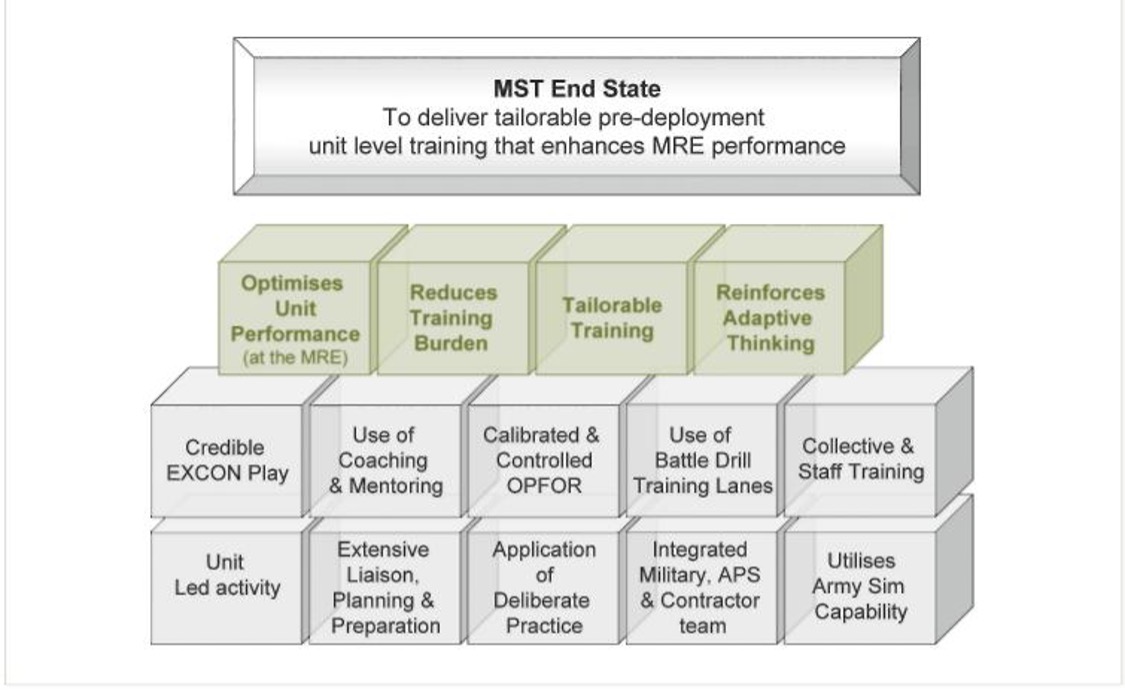

The MST objective is to ensure that units are better prepared for mission rehearsal exercises. The various ‘building blocks’ that underpin MST also produce a number of key benefits which result from and contribute to the desired end-state. These are illustrated in Figure 1.

MST provides commanders and key staff the opportunity to practise and learn in the early stages of the force preparation cycle. MST can also be used to provide sustainment training, particularly for units with high personnel turnover, in order to capture subject matter expertise and experience. Changes to key leadership positions in a unit following a deployment tend to erode the experience base of the unit. With the current high operational tempo, standard operating procedures, reporting procedures, tactics and techniques need to be taught quickly to new personnel and rehearsed collectively so that the unit retains its operational effectiveness. This ensures that any weaknesses are identified early and can be addressed prior to the unit’s mission rehearsal exercise.

Preparation time immediately prior to a deployment is limited, particularly if the unit is being rounded out through attachments from other units. Deploying units often do not have sufficient people, time and resources to properly train in both individual and collective skills. Resources may also be retained by higher headquarters because of tight deployment schedules, land restrictions and logistics constraints. Most unit commanders welcome any support that assists force preparation programs and provides relief for unit headquarters staff and subordinate commanders.

Figure 1. MST building blocks and key benefits.

As MST is an activity based on collaboration between the unit and Army Simulation Wing, there is a high degree of flexibility in the type of training environments that can be used. MST is designed to achieve training objectives in the time available as part of the unit’s pre-deployment training. During the conduct of MST activities there is some scope to adjust the training tempo and repeat activities to practise key procedures under varying conditions.

Adaptive thinking is an active process—it is a form of behaviour. Repetitive performance allows thinking processes to become automatic so that they can be performed quickly and accurately with less mental effort. As more elements become automatic, complex models can be developed without a proportionate increase in mental effort. This allows experts to use their knowledge flexibly and creatively in complex situations. An increase in automatic action and cognitive flexibility is characteristic of expert performance. By providing an opportunity for units to conduct repetitive training, MST subjects units to greater pressure during the mission rehearsal exercise, allowing a more rigorous application of their techniques and procedures.

The Next Steps

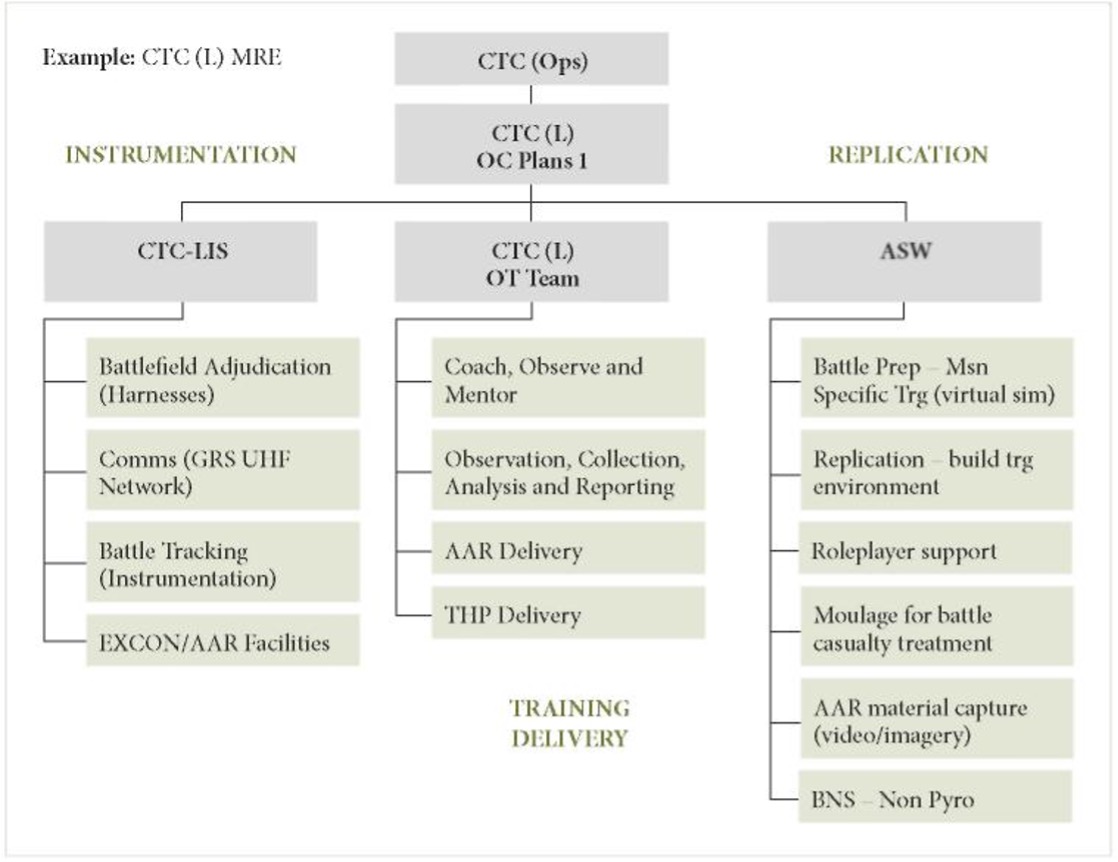

Early 2010 has seen the integration of the Combat Training Centre and Army Simulation Wing capabilities and led to the adoption of a partnered planning approach between the two organisations. This has led to greater recognition of the way each organisation can best support unit force preparation. The approach that will see the current simulation capabilities within Army combined to deliver the optimum effect in terms of replication, instrumentation and training delivery is still evolving. Initial discussions between the Combat Training Centre and Army Simulation Wing have led to the proposal of a possible model for training within the live simulation domain, illustrated in Figure 2.

The integration of virtual and constructive simulations was also tested in MST activities in late 2009. Command teams experienced virtual immersion in computer-aided training scenarios that were linked as part of the command post exercise. Those involved in these virtual vignettes regarded this as highly effective training. Ideally, the Combat Training Centres ‘Road to War’ construct will be characterised by further progress in the optimum application of simulation technology.

Figure 2. Combat Training Centre/Army Simulation Wing live training integration.

Conclusion

The last five years have seen significant development in the application of simulation training within the Army. The former Army Simulation Wing MST program has been one of these developments. The program provided commanders with the ability to train within their unit location and tailor their training to hone their unit’s core skills through the application of deliberate practice.

While the MST program has enjoyed some success, Army Simulation Wing still faces a number of challenges before its role in MST and, to a larger extent, in simulation itself, are fully embraced by the Army. These challenges primarily concern the synchronisation of Army Simulation Wing support to individual and collective training activities within the force preparation continuum. Thus far, progress towards the integration of Army Simulation Wing into the LCRC ‘Road to War’ has been encouraging.

As the Deputy Director of Simulation Development, Robert Carpenter, stated in 2005, ‘the challenge is to institutionalise [the] use [of simulation] and continue to demonstrate its value’.6 Likewise, the initiatives of the former MST program, particularly its use of simulation, must also be ‘institutionalised’ to ensure that its benefits for the Army are maintained and sustained over the foreseeable future.

Endnotes

1 Australian Army, COMD LWDC Directive 04/09 – Transition of the Army Simulation Wing Mission Specific Training Program to the Land Combat Readiness Centre, Department of Defence, 14 December 2009.

2 Australian Army, Adaptive Army – An Update on the Implementation of the Adaptive Army Initiative. This differs from a mission rehearsal exercise which is defined as ‘a realistic, relevant and demanding training environment that will deliver into theatre a cohesive and sustainable force element thoroughly prepared, practiced in and capable of executing all expected operational tasks’. See p. 12.

3 KA Ericsson, RT Krampe and C Tesch-Roemer, ‘The Role of Deliberate Practice in the Acquisition of Expert Performance’, Psychological Review, Vol. 100, 1993, pp. 363–406.

4 A Ericsson, The Road to Excellence: The Acquisition of Expert Performance in the Arts and Sciences, Sports and Games, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1996, pp. 1–20.

5 M Cohen, J Freeman and B Thompson, ‘Critical Thinking Skills in Tactical Decision-Making: A Model and a Training Method’ in J Canon-Bowers and E Salas, Decision-Making Under Stress: Implications for Training & Simulation, American Psychological Association Publications, Washington, 1998, p. 155.

6 Robert Carpenter, ‘Australian Update 2005’, presentation to IITSEC, Department of Defence, Puckapunyal, 2005, p. 16.