Abstract

As the Australian Defence Force (ADF) embarks on an ambitious re-equipment program involving the procurement of multi-billion dollar platforms, enhancement of the logistics required to support this technology will also require careful consideration. Autonomic Logistics is a system that offers the ADF the opportunity to link the current Military Integrated Logistics Information System (MILIS) to real-time platform information through the employment of the Sense and Respond Logistics system. This is a proven system that has demonstrated its effectiveness within the United States (US) forces and can work equally well within the ADF.

‘The line between disorder and order lies in logistics...’

– Sun Tzu

Introduction

The ADF is in the midst of an evolutionary change. Whether it is labelled Network Centric Warfare (NCW), Network Centric Operations or Network Enabled Operations, this change concerns the ability to share information seamlessly in order to conduct effective operations into the future. This ability to share information is referred to as the ‘network dimension’ and has the facility to:

• connect units, platforms and facilities through networking, appropriate doctrine, training and organisational processes and structure

• collect relevant information using networked assets and distribute it via the network

• use the information, and the intelligence derived from it, to achieve military objectives

• protect the network from external interference or technical failure.1

This article will focus on the two ‘Cs’—connect and collect—and the way the ADF can develop these abilities, documented extensively in the ‘NCW Roadmap’. The Roadmap envisages an ADF in which:

• key logistic function networks within the national support area are linked with those in theatre and provide connectivity and a collaborative ability with industry and coalition partners

• commanders have end-to-end visibility of the logistic system, allowing them to rapidly and effectively prioritise the resources required to generate and sustain deployed force elements

• automated ordering and replenishment occurs as supplies and ordnance are consumed by platforms and field units

• the deployed force has minimised its vulnerabilites and significantly enhanced its mobility through more effective reach back, optimum force presence and precision sustainment for the majority of logistics requirements.2

Yet, based on a review of the NCW Roadmap and the assumption that the supported projects will achieve their desired states, the ADF will still only partially achieve its goal in the critical area of logistics. This is because of the existence of a residual ‘air gap’ at the platform end of the logistics continuum preventing commanders from accessing aggregated, real-time logistics data from the ‘foxhole’.3 As a consequence, the decision-making ability of the operational commander will be less than optimal. Critical support costs will also be higher than necessary. MILIS alone is incapable of generating the data required by the commander in the field, while Autonomic Logistics was developed primarily to meet the needs of the supply pipeline rather than optimised for the support of operational commanders. Sense and Respond Logistics, on the other hand, combines all the required components to present the commander with complete visibility of the logistics chain.

This article will define the concepts of Autonomic Logistics and Sense and Respond Logistics, and provide an overview of their use through two civilian applications. The way Autonomic Logistics works will be explained with reference to a ‘foxhole to factory to foxhole’ continuum of combat service support and the concept of Autonomic Sustainment currently being developed by the United States Marine Corps (USMC) will also be examined.

What Are Autonomic Logistics And Sense And Respond Logistics?

The term ‘autonomic’ refers to the autonomic nervous system within the human body which controls involuntary actions such as breathing or heartbeats which occur without conscious prompting.4 Likewise, an Autonomic Logistics system is designed to function autonomatically without any form of prompting.5 The Autonomic Logistics system discussed here was first developed by Lockheed Martin to support the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter. The main elements of this system are the sensors embedded in the Joint Strike Fighter itself to facilitate prognostics and health management.

For ease of comprehension, the concept of prognostics and health management can be broken into two definitions. Prognostics is defined as ‘the actual material condition assessment which includes predicting and determining the useful life and performance life remaining of components by modeling fault progression’. The concept of health management involves ‘the capability to make intelligent, informed, appropriate decisions about maintenance and logistics actions based on diagnostics/ prognostics information, available resources and operational demand’.6

Prognostics and health management generate data which connects directly to the Autonomic Logistics Information System which, in turn, links the aircraft to the Lockheed Martin facility in the United States through the supply chain and intermediate supporting elements. In the case of the Joint Strike Fighter, the Autonomic Logistics Information System analyses the data obtained from key components on the platform and, where necessary, organises a maintenance event, including the required components, technicians, specialist equipment and tools, necessary consumables and hangar space. The system may even schedule the fighter’s availability as required.

While the Autonomic Logistics Information System optimises the efficiency of resource supply the analogy with the human autonomic system should not be ignored. The system functions automatically but it does not think or reason. Deviations required for operational contingencies are not automatically factored into the process. This is where the human element, trained to appreciate and respond to a range of operational variables, becomes important.

Two examples of current practice illustrate the successful application of the Autonomic Logistics Information System in the less complex civilian environment. Autonomic Logistics is employed extensively in the Australian mining industry by heavy equipment vendors, such as Caterpillar, as an element of condition-based maintenance. Sensors embedded in major components of the equipment collect data, which is downloaded into an information system every time the vehicle comes within range of a receiving device. This works well within the confines of a mining site where equipment circulates in a limited area. A more challenging application of the Autonomic Logistics Information System occurred with QANTAS’s purchase of the Airbus A380. This required a more tailored application of the system, known as AIRTRAC: ‘QANTAS Airbus AIRTRAC system provides a link between the airframe and a dedicated support facility staffed with specialist engineers available 365 days a year.’7 Furthermore, ‘the A380’s onboard software monitors every system and instantly sends an email to AIRTRAC if any anomaly is spotted. The instant the email is received, the required part is ordered so it’s ready for the arrival of the A380.’8

QANTAS’s application of Autonomic Logistics through the AIRTRAC system focuses on bringing together the various elements required for maintenance. This approach represents a departure from scheduled maintenance programs, which are usually based on calculated intervals. Scheduled maintenance involves extensive safety margins intended to prevent failure of the component, but includes, of necessity, significant waste of resources through the replacement of items that are still within their safe, serviceable life. Conversely, condition-based maintenance provides ‘the ability to predict future health status of a system or component, as well as providing the ability to anticipate faults, problems, potential failures, and required maintenance actions’.9 The aim of condition-based maintenance is to compare the current condition of a component with that required under safety specifications and arrange for timely repair or replacement prior to failure.

In the military context, however, additional considerations intervene in the scheduling of a maintenance event. Sense and Respond Logistics, defined by the Office of Force Transformation as ‘... a transformational network-centric concept that enables Joint effects-based operations and provides agile support’, involves the same system elements as Autonomic Logistics, but also incorporates the ability to vary actions based on local operational decisions.10 Such variations could include the repair of equipment by its operators rather than a specialised repairer or, in an operational context which may preclude the removal of the machine for repairs, its use in a reduced capacity.

Equipment health monitoring systems have been in use for decades. One such system was developed by Pratt and Whitney for jet engines used in the F-15 and F-16. The engine monitoring system, which consists of both engine diagnostics and ground diagnostics units, records the operating conditions as well as any anomalies in the performance of the aircraft. Once the aircraft is on the ground, the ground diagnostics unit is plugged into the engine diagnostics unit and the data is downloaded for analysis. The commercial arm of the company applies its engine monitoring system not only to other commercial aircraft engines, but also to automobiles. When a car is taken to a workshop to be serviced, technicians hook it up to a diagnostic analyser—a machine developed from the engine monitoring system—to determine the scope of work required to maintain the vehicle adequately. There is usually no real-time connectivity between the vehicle and the diagnostic system and only data detailing what has already occurred can be downloaded and processed.

The Defence Science and Technology Organisation (DSTO) also uses prognostics and health management systems—usually referred to as ‘health and usage monitoring systems’. Until recently, these applications required data to be physically downloaded and transferred for analysis. Both the Autonomic Logistics and Sense and Respond Logistics systems take this process a step further, also including prognostics. The sensor suite located in the platform compares performance data to predetermined standards in order to predict the status and longevity of the component. USMC light armored vehicles (LAV) connect health and usage monitoring systems to a Sense and Respond Logistics system so as to detect component wear and mechanical faults within the vehicle. For example, the LAV may transmit data on the condition of the main wheel bearing on the right front shaft to the Sense and Respond Logistics system, which then calculates that it is likely to fail after twenty hours of further use. Data from the vehicle is continuously transmitted and downloaded for analysis of the vehicle’s performance (see Figure 1, page 64).

The US Army makes frequent use of Sense and Respond Logistics systems to:

... maximise the readiness and logistics effectiveness of the force. S&RL [Sense and Respond Logistics] requires a network-centric enterprise and mandates collaboration within and across communities of interest. The second goal of S&RL is enabling the logisticians to accurately observe, orient, decide and act faster than the supported customer. Improving the logisticians decision cycle enables more accurate and timely support to the warfighter. With the integration of tracking, platform autonomics, information technologies and flexible business rules, logisticians will be able to proactively sustain the dynamic battlefield of the 21st Century.11

The old concept of ‘Factory to Foxhole’ is now ‘Foxhole to Factory to Foxhole’.12

Logistics Costs

When a new system is acquired, the estimate of its life cycle costs is based on the generally accepted premise that the system itself accounts for one third of the cost. Logistics and operational costs comprise the other two thirds. The Australian Joint Strike Fighter program provides a useful example:

The true cost of owning a modern jet fighter includes 25 or 30 years of maintenance support, and pilot and ground crew training, and this is often twice or more the original purchase price. The JSF program includes a global logistics sustainment system ... That doesn’t include the cost of fuel and weapons.13

The Australian Government opted to purchase one hundred Joint Strike Fighters. Applying a per aircraft cost of US$50 million, this amounts to a total purchase of US$5 billion. Support and operating costs equate to US$10 billion for a program cost of US$15 billion. Lockheed Martin, supplier of the Joint Strike Fighter, estimates a 20 per cent reduction in the logistics costs over the life cycle of the aircraft due to the application of Autonomic Logistics. This equates to a US$2 billion saving for the Australian Joint Strike Fighter program.14 Of course, these costs do not include the investment required to upgrade the platform and the purchase of requisite items and infrastructure that will provide a ‘whole of life’ use of this aircraft.

If the same concept is applied to the Australian Light Armoured Vehicle (ASLAV), the original cost would also include:

• acquisition cost (US$2 million/unit 257 units): US$514 million

• projected whole-of-life logistics cost: US$ 1.028 billion

• 20 per cent savings: US$205.6 million on operating costs over the life of the ASLAV.

Obviously this comparison does not take into account the fact that the original unit cost would have been greater with the addition of sensors, communications equipment and upgraded logistics resources. However, it does illustrate that a relatively modest increase in unit acquisition cost could lead to significant savings in logistics expenditure. The comparison also ignores the fact that the ADF has a history of retaining assets for extended periods (as it did the F-111 and M-113AS). This implies increased logistics to acquisition cost savings due to the comparatively long service life of many Australian platforms. Given the number of new equipment acquisitions scheduled in the Army capability development contiuum, the embedding of prognostics and health management devices makes sound financial sense.15

End-To-End Visibility

In their operational application, Autonomic Logistics and Sense and Respond Logistics systems are anchored at the platform level—the ‘foxhole’—while the destination at the other end differs according to who ‘owns’ the system (the ‘factory’). In the case of the Joint Strike Fighter, the ‘factory’ is Lockheed’s facility in Denver in the United States. Lockheed has visibility of the entire supply chain via the Autonomic Logistics Information System, which is an integrated component of the Joint Strike Fighter program.

The Sense and Respond Logistics concepts discussed here are based on the USMC application. The USMC’s Sense and Respond Logistics system supports both the logistics/supply chain and its operational application. Data gathered for current level usage is transmitted to the next level in the chain of command for aggregation and review:

With information technology, S&RL receives, recognizes and responds to consumption and requirement patterns through the use of equipment embedded Intelligent Agents. S&RL leverages the capabilities of network-enabled forces to share logistics information, share a common perspective of the battle space, and provide early awareness of consumption and needs, allow commitment tracking and allow for reconfiguration of the logistics system when needed. It will tell the Commander “how much fight is left” in his units.16

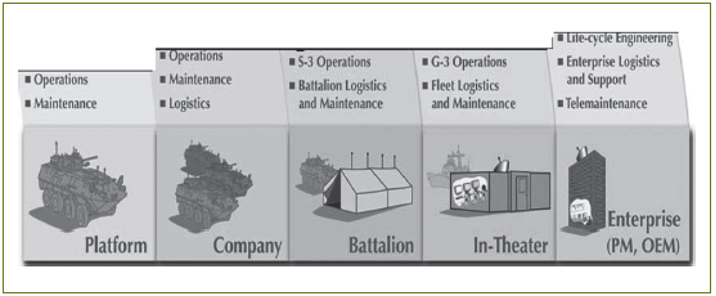

Figure 1 illustrates how accummulated and aggregated data provides input to the decision-making process at various levels:

Figure 1. Overview of Sense and Respond Logistics.17

The logistics projects listed in the NCW Roadmap do not appear to achieve the optimal goals of the NCW vision because MILIS does not ‘reach forward’ sufficiently to obtain platform-specific data. The ADF NCW implementation plans for logistics are based on MILIS (Project JP 2077). While MILIS is an automated supply and replenishment system, and is significantly advanced within current practices, it does not have real-time access to information on the consumption of resources and ordnance as there is an ‘air gap’ between the system and the individual platforms. Although this gap is projected to narrow with the forecast extension of MILIS to sub-unit level, it will not close at the critical platform level.

With the connection of Sense and Respond Logistics to MILIS, a commander could access advice based not only on current and previous performance, but also the projected health of the assets under his/her control. Since all resources would be identified by part number and location, they could be redirected immediately to meet higher priority requirements. This means that supportability and sustainability decisions could be based on accurate data rather than a ‘best guess’ derived from historical patterns.

Towards Autonomic Sustainment

The USMC and the US Army have both embarked on programs intended to lift the ‘fog of war’. The USMC vision for Sense and Respond Logistics is:

Marine Corps S&RL is an approach that yields adaptive, responsive, demand driven support for force capability sustainment. The prime metrics for S&RL are speed and effectiveness, relative to commander’s intent, which predicts, anticipates, and coordinates actions that provide an operational advantage spanning the full range of military operations across the strategic, operational, and tactical levels of war. S&RL gives the Operational Commander an increased range of support options that are synchronized with the operational effects. The concept is built upon characterizing and anticipating support problems, early identification of potential constraints, and rapid response to changes in operational tasks and reprioritization.18

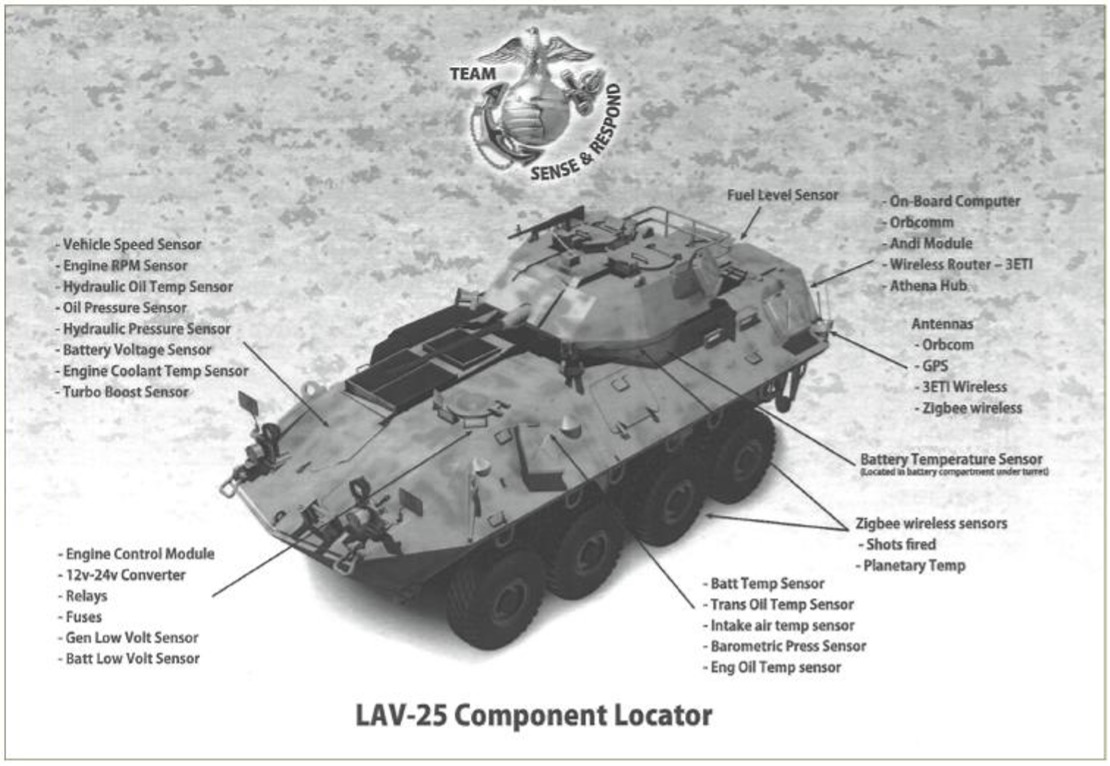

The USMC Sense and Respond Logistics program commenced in July 2008 with the fitting of a sensor suite to LAV-25 platforms (see Figure 2).19 The retrofit of the entire LAV fleet was projected to be completed by March 2009 (although the timeline has slipped slightly), with plans in place to extend the program to several other platforms in service with the USMC.20

Figure 2. LAV embedded platform sensors.21

Figure 2 illustrates the value of the information generated to the platform’s operator. This was also starkly apparent during the USMC deployment in Iraq when the planetary hub reduction gear case in some of the LAVs began to overheat, requiring a crew member to dismount and touch the unit to check whether it was running hot.22 The addition of real-time, aggregated logistics data, plus enhanced operational situational awareness are natural consequences of the improved connectivity created by Sense and Respond Logistics. Sense and Respond Logistics provide decision-makers in the chain of command a more accurate and timely gauge of platform condition and the status of critical classes of supply including fuel and ammunition, allowing more effective use of the assets at their disposal and the more efficient function of the logistics system overall.

In future it may be possible to utilise improved situational awareness, provided by a system similar to ‘Blue Force Tracking’ currently employed on operations by US forces, to focus logistics support on the elements best placed to receive or most in need of resupply. For example, combat teams that have been in contact and require replenishment could be differentiated from those that have experienced a relatively low tempo of operations. Some progress has been achieved in automatically providing convoy commanders alternative routes to avoid enemy action or other disruptions to supply routes, thereby delivering supplies at a reduced risk.23

Commencing with the LAV25 project, the USMC is developing and extending Sense and Respond Logistics into a concept of autonomic sustainment.24 This offers the potential to provide end-to-end visability of the health of platforms, maintenance events, and the status of the supply chain. The US Department of Defense believes that the incorporation of Sense and Respond Logistics into the current logistics systems is possible, and indeed, desirable:

Contrary to popular belief, S&RL can be implemented without replacing most of todays major critical systems. That is, S&RL can be an enhancement to current DoD systems since, by design, it adds only a thin layer of functionality over the existing systems.25

Many of the required component information systems required to provide visibility of the supply chain are already included within the scope of Project JP2077. Through an extension of MILIS to interface with Sense and Respond Logistics, the ADF has the opportunity to achieve a broader span of the logistics continuum from ‘foxhole to factory to foxhole’ and fulfill the logistics goals identified in the NCW plan.

Conclusion

Logistics considerations will become increasingly important as the Army capability development continuum progresses. The ambitious acquisition plans projected for the ADF, combined with the related necessity to deliver significant cost savings in the defence budget through improved efficiency highlight the need for a logistics system that also provides effective, adaptable and flexible combat service support. In its projected form, MILIS will not integrate real-time platform level or aggregated information derived from a Sense and Respond Logistics system. USMC experience with the LAV25 has illustrated clearly the benefits of an Autonomic Logistics system in providing accurate and reliable logistics information to commanders at the tactical and operational levels.

In order to provide a full spectrum of ‘foxhole to factory to foxhole’ logistics for the Army and the ADF, MILIS must extend its reach beyond logistics centres to connect at the platform level in real time. Modern logistics systems such as Sense and Respond Logistics and Autonomic Logistics are now proven concepts in the civilian and military environments. The Army has an opportunity to trial, and possibly implement, Autonomic Logistics by applying Sense and Respond Logistics technology to platforms shared with the USMC, such as the ASLAV, and link this to MILIS to create an integrated Autonomic Logistics information system that will realise the logistics goals identified in the NCW Roadmap.

Endnotes

1 Based on the definition cited by the Defence Science and Technology Organisation (DSTO) in its discussion of the Australian NCW concept and the specific aspects of the network dimension. The original definition was developed by the Directorate of Future Warfare. See T McKenna, T Moon, R Davis and L Warne, ‘Science and Technology for Australian Network-Centric Warfare: Function, Form and Fit’, Australian Defence Force Journal, No. 170, March/April 2006, p. 5.

2 Ibid., p. 10.

3 Ibid.

4 R Hingst and G Gunter, ‘Autonomic Logistics: An Infrastructure View’, The Australian JSF Advanced Technology and Innovation Conference, Melbourne, 2008.

5 ‘F-35’, Lockheed Martin F35 program, autonomic logistics, <http://www.jsf.mil/program/prog_org_autolog.htm>.

6 Defense Acquisition University, ‘Prognostics & Health Management (PHM) and Enhanced Diagnostics’, Acquisition Community Connection, <https://acc.dau.mil/CommunityBrowser.aspx?id=128766>.

7 G Thomas, ‘Magic carpet ride’, QANTAS the Australian Way, December 2007, p. 38.

8 Ibid.

9 Defense Acquisition University, ‘Prognostics & Health Management’.

10 Office of Force Transformation, Operational Sense and Respond Logistics: Coevolution of an Adaptive Enterprise Capability, Department of Defense, Washington DC, 2004, p. 5.

11 B Chin, ‘Sense-and-Respond Logistics Evolving to Predict-and-Preempt Logistics’, Army Magazine, May 2005, <http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa3723/is_200505/ai_n13636351>.

12 Hingst and Gunter, ‘Autonomic Logistics’.

13 G Ferguson, ‘Customers join to deal a price’, The Australian, 7–8 June 2008, p. 3.

14 Lockheed Martin, ‘Lockheed Martin Combines OEM Expertise with Low Cost Services For Total Life Cycle Support of Aircraft’, Earth Times, 19 June 2007, <http://earthtimes.org/articles/show/news_press_release,125073.shtml>.

15 ‘The Army’s Continuous Modernisation Process’, Vanguard, Issue 2, June 2009, <http://www.defence.gov.au/army/lwsc/docs/vanguard_002.pdf>.

16 US Marine Corps, ‘Concepts and Programs’, Program Assessment and Evaluation Division, HQMC, (P&R< P&AE), Pentagon, Washington DC, 2009, p. 147, <http://www.hqmc.usmc.mil>.

17 Source: USMC Team Sense & Respond, (n.d.) <http://www.usmc-srl.com>.

18 Ken Lasure, ‘Sense and Respond Logistics: Game Changer or “Beltway Buzzword?”‘, The TCG Pulse, Fall 2009, pp.2, 10–11, <http://www.columbiagroup.com/newsletters/TCG%20Pulse%20Fall%202009.pdf>.

19 E L Morin, ‘Autonomic Logistics (AL) CBM+’, Marine Corps Systems Command, 28 November 2007, <http://www.acq.osd.mil/log/mrmp/cbm+/Briefings/USMC_AL_brief_28Nov07.ppt#588,2,ALStatus>.

20 USMC Team Sense and Respond.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid.

23 A Caglayan, ‘Risk Based Route Planning for Sense and Respond Logistics’, Military Logistics Summit 2009, Institute of Defense and Government Advancement, Washington DC, 8 June 2009.

24 USMC Team Sense and Respond.

25 Office of the Deputy Under Secretary of Defense For Logistics and Material Readiness, Sense & Respond Logistics Technology Roadmap, Executive summary, Washington DC, March 2009, <http://www.cougaarsoftware.com/srl/OSD_report/SRL_Technology_Roadmap_Exec_Summary_Mar_2009.pdf>.