Abstract

The recently endorsed and released Adaptive Campaigning had been cited as ‘fundamental to achieving the Adaptive Army’. The late Colonel John Boyd, USAF, famed for his work on the ‘OODA loop’ also conducted a considerable amount of research on adaptation in times of conflict and peace. This article reviews the lessons that Army could learn from his work. The article also argues that some elements of his work have been corrupted in Adaptive Campaigning, in particular the new ‘Adaption Cycle’ seen as central to the concept. Work by Boyd and other theorists on adaptation is then discussed in the context of Adaptive Campaigning. The article concludes by highlighting some real tensions in the theory of adaptation and the current state of the Army and the Australian Defence Organisation.

Just as the old German manuals had stamped on the examples provided ‘not a formula’ so Boyd’s ideas cannot be applied in cookie cutter fashion... As it is reduction of Boyd’s thinking to ‘Boyd’s simple version of the OODA loop’ is already unfortunately well advanced.

– Lexington Green1

Introduction

There is a call in military circles, owing to the increasing complexity of conflict, to be continuously adaptive. The shift to what Rupert Smith has classified as ‘war among the people’2 has driven Western armies to be more culturally aware and demanded increased flexibility and breadth in combat leaders. Kinetic effects (killing people and smashing things) alone are no longer the raison d’etre for the modern counterinsurgent army.

‘Adaptive’ as defined in the Oxford English Dictionary is ‘to make suitable for a new use’, or ‘become adjusted to new conditions’. Both definitions for any large organisation such as the Army pose challenges beyond simply recognising the new. In business, companies that fail to adapt to new market forces will see immediate effect on the balance sheet and in the long term will imperil their very existence. Defence forces seldom have a chance to benchmark prior to the call to task, and rarely will the red ink be seen prior to failure. This makes both the importance and difficulty of adapting high. Some have acknowledged that military organisations can be extremely adaptive.3 This has not been consistently the case and in some cases, the need to adapt is forced upon us in the cradle of conflict itself.4

In dealing with this new environment, the Australian Army has recently formalised its Future Land Operating Concept – Adaptive Campaigning.5It has had a long and extensive gestation. With over twenty-two versions raised over the last two years, it has seen many revisions. During these revisions, the core tenets have not changed. Mission command, five fixed lines of operation, the dominant narrative and the ‘Adaption Cycle’ have remained continuous themes throughout. Not one major concept appears to have received any significant modification over two years of development.

The Chief of Army has placed Adaptive Campaigning ‘as fundamental to achieving the Adaptive Army’.6 This is a weighty responsibility for a paper that only has fifty-four pages directly dealing with the concept. Over one third of these pages articulate the environment previously defined in the excellent Complex Warfighting concept.7 Adaptive Campaigning is an important document, yet little real debate has appeared on the concept.

The purpose of this article is to look at Adaptive Campaigning primarily through the lens of the one of the most innovative military thinkers of the late twentieth century, Colonel John Boyd. This article will bring other military and business theories to this discussion, many of which parallel Boyd’s primary theories. It will focus on a pivotal element of Adaptive Campaigning, the ‘Adaption Cycle’, and then broadly look at Boyd’s theories on adaptation beyond the confines of Adaptive Campaigning. I will contend that Adaptive Campaigning as a concept does not go far enough to achieve the Chief of Army’s intent.

Colonel John Boyd, USAF

The influence that John Boyd has had on Western military thought and capability is significant. Boyd by any standard was a zealot, working long hours and letting no one get in his way. While serving as a fighter pilot instructor, he initially focused on the development of air-to-air combat tactics and then shifted to the aircraft design criteria that affected this. An irascible character, he offended many and only survived militarily by overwhelmingly being right more often than wrong.

After a turbulent relationship with the USAF, they and Boyd parted ways in 1975.8 He started to expand his interest into conflict in general. The US Army and, even more so, the US Marine Corps drew on his work to develop fighting concepts that have served them well in the past decade and a half. Boyd’s research ranged from Sun Tzu to Richard Dawkins to the quantum work of Werner Heisenberg, often taking elements of such work and stitching them back together into a new form. This provided an innovative (even adaptive?) process from which to draw deductions. His thirty years of feverish, argued and considered study does not boil down to one simple loop diagram? To many, Boyd’s ideas remain incomplete; this is probably how he would have wanted it; some are contentious, something he no doubt would have relished.

In terms of leaving a legacy for future apostles, Boyd was a poor messiah. He seldom published any papers, and those he did are difficult to read.9 Boyd developed sometimes hours-long slide presentations, which were continuously updated. He would not develop concise versions, even at the request of very senior US defence officials. If you wanted Boyd’s thoughts, you got them all. Boyd was also concerned that publication would freeze his views, something that was an anathema to him. While all this ensured continuous development, it discouraged the wider debate that the greater transmission of his ideas would have allowed. Fortunately, two recent biographies and Dr Frans Osinga’s recent publication of his PhD work on Boyd have rectified this.

The OODA Loop

Boyd derived the OODA loop from the study of air combat in Korea. Theoretically the Soviet designed fighter of the time, the MiG-15, was a superior aircraft, yet Allied pilots in the F-86 Sabre were able to achieve a greater level of kills. A US Air Force pilot was able to Observe (owing to a higher canopy, giving a better all around view), Orient (owing to hydraulic powered flight controls), Decide (better training) and Act (a combination of all factors) better and therefore faster than a MiG-15 pilot (the OODA loop or Decision Cycle).10

The benefits to a combatant in using this cycle faster, that is the focus on the tempo within this loop, than an adversary is referred to as getting inside his OODA loop. To be able to take action faster renders the adversary disoriented and ultimately dislocated from the situation, leading to defeat.

The OODA loop has received widespread discussion and assimilation into concept in both defence and business circles. It has also attracted critics, and a few moments’ reflection could lead anyone to think of counter arguments to the concept, such as:

• What if an enemy’s concept of operations is accepting of a slow decision tempo, regardless of what its adversary does (a protracted guerrilla campaign)?

• What if an enemy has such mass that the actions taken, while causing ‘localised’ damage, do not affect his overall plan? Providence can still lie with the big battalions.

• The simplified loop is vulnerable to deception operations; the drive for tempo may become a drive to haste.

• The operating environment itself may prevent your force operating at the tempo you desire.

However, the simplified OODA loop has great utility. It is an immensely important tool for the basic understanding and planning of operations, particularly at the lower tactical level. It provides an excellent tool for teaching and understanding tactics and is intrinsic to the Military Appreciation Process (both joint and single service).11 Yet, in no part of Army education does its importance seem emphasised!

The ‘Adaption Cycle’12

The current iteration of Adaptive Campaigning states that the Adaption Cycle does not replace Colonel John Boyd’s OODA loop... The Adaption Cycle emphasises understanding a problem through experience, knowledge and planning’.13 The ‘Adaption Cycle’ places Action as the first step in a continuous loop moving next to ‘Sense’, then ‘Decide’ and then Adapt’. Adaptive Campaigning argues that a complex adversary/situation cannot be known until it is probed/tested.

This contrite explanation did not appear in previous editions of Adaptive Campaigning. Nor in previous versions was there any acknowledgment given to John Boyd’s OODA loop. Unfortunately this correction does not fix the underlying flaws and raises further questions. On which particular form of Boyd’s OODA loop is Adaptive Campaigning commenting? How did such an esteemed strategist and air combat veteran miss the need for adaptation, mission command and flexibility of mind in the conduct of war—things the Adaption Cycle’ apparently considers? Additionally the Army has been formally teaching mission command since the late 1980s; do we have it so wrong that we need further reinforcement through the Adaption Cycle’?

I will demonstrate that Boyd missed none of this and that we have ‘dumbed down’ a lifetime of innovative and relevant work. This is not a promising start for a key foundation for the future Army.

The authors of Adaptive Campaigning did not see the OODA loop as capable of dealing with complexity nor applicable at higher levels of conflict; hence, the derivation of the supplemental ‘Adaption Cycle’. However, when you look at Boyd’s last version of the OODA loop, which was formed over the last decade of his life, it does deal with complexity. Indeed, dealing with complexity and the need to adapt permeates Boyd’s later work.

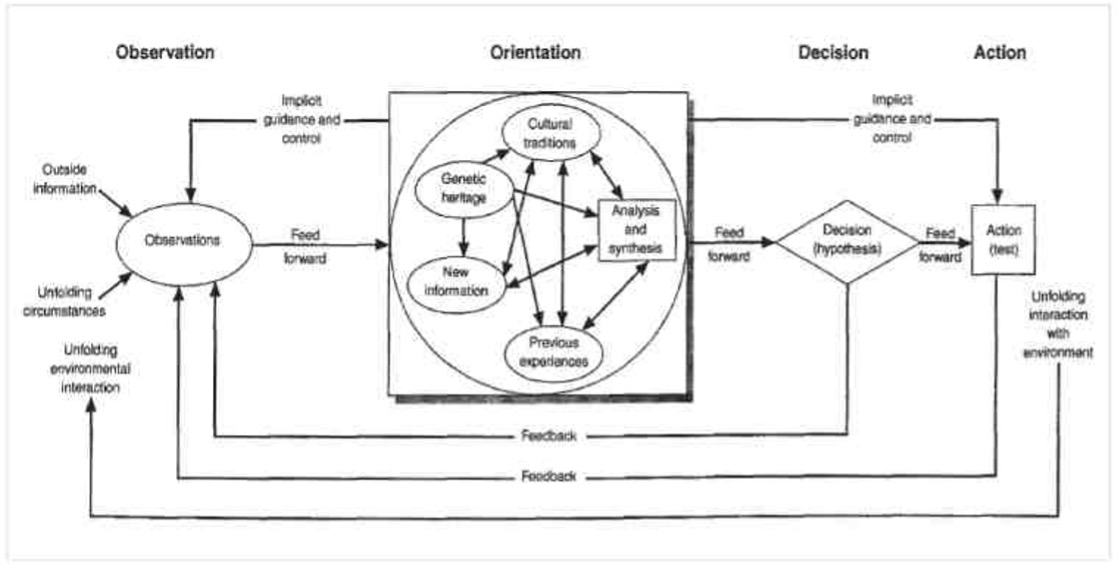

Figure 1. The ‘real’ OODA loop14

Osinga calls this the ‘real’ OODA loop. However, it would be better to state that it was Boyd’s last version. I find it hard to believe that if he were still alive now, we would not be considering another amended diagram. As we can see it is not a closed system, and even a cursory examination shows that it demands mission command (top line implicit guidance and control). Studies of other slides generated by Boyd indicate that he understood the complexity of insurgent/terrorist operations and indeed the strategic level of conflict.15

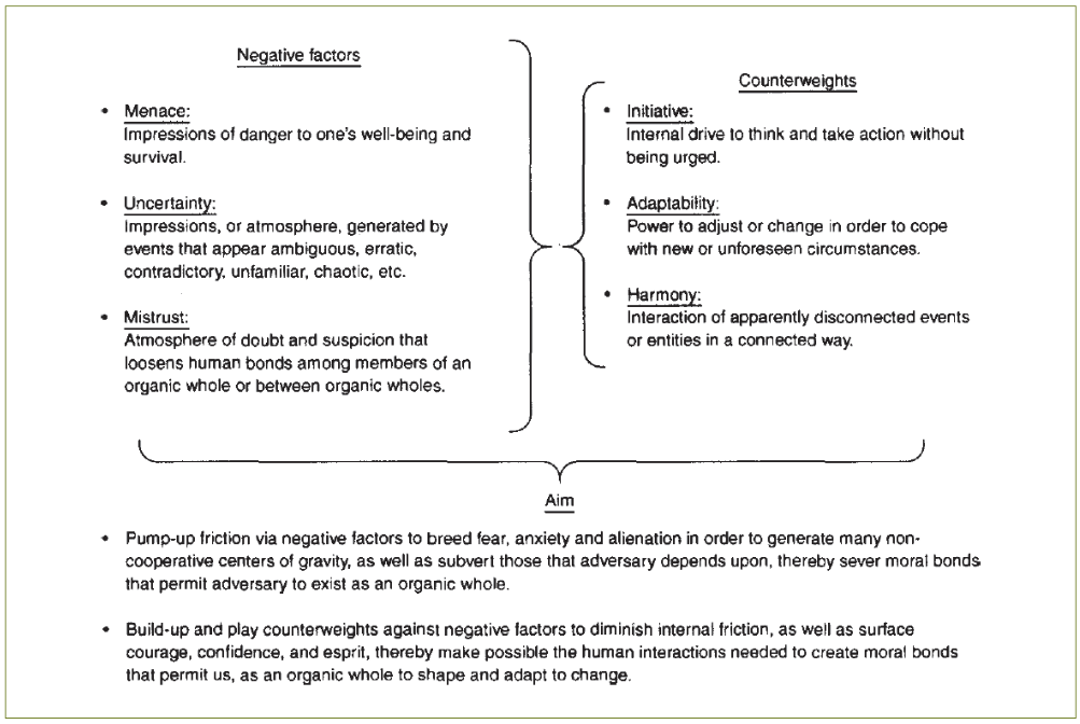

Figure 2. The essence of moral conflict16

Boyd And Adaptation

We can see without going into the origins of his analysis that Boyd was placing initiative and adaptability central to victory in conflict. He also recognised something not formally acknowledged by the Australian Army: the need for harmony (trust in all directions), a factor that has been recognised by other armies in the past apparently fighting simpler wars!17

If we are going to consider adaptation as the keystone for the Australian Army of the future, we have more to learn from the master’s voice. Some experts dealing with complex systems tend to reject distillation of a problem into simple components— reductionism. Unfortunately for the military combat leader, other factors force the opposite effect. Fear, fatigue and stress all deteriorate higher cognitive functions.

Drills and standard procedures mitigate this (set patterns). Reductionism is an essential component of success in combat. Adaptive Campaigning states that its concept includes the lessons of recent operations and DSTO analysis. It is difficult to conceive this lesson not being present.

Some may say this is not that necessary at the operational or strategic level of conflict, but these levels have their own time sensitivities and pressures that impair decision-making. Boyd placed great emphasis on intuitive thinking—the term he used is ‘pattern matching’.18

Before taking discussion of either the ‘Adaption Cycle’ or the ‘real’ OODA loop further, there are other legacies from John Boyd we need to discover. Osinga summarises them as:19

Tempo: Boyd places emphasis on the speed of decision-making. He also stressed the importance of changing speed in order to be unpredictable. Additionally, it must be translated into meaningful action; by itself, ‘information superiority’ is useless.20 Tempo is only one area that needs to be exploited. Adversary main efforts and deep objectives must also be considered. Enemy cohesion cannot be shattered by irregular tempo alone.

Orientation: To Boyd, great decision and magnificent actions counted for nothing if the commander was not oriented. Orientation was the essential component of the OODA loop. As already stated, Boyd favoured an experiential learning base that enabled a leader to adapt to a situation by having a ‘repertoire of orientation patterns and the ability to select the correct one’.21 The ability to re-orient (adapt?) is vital, but in conflict, the mechanism had to simple and intuitive.

Organisational Adaptation

Adaptation and the ‘mechanisms’ of adaptation are perhaps key themes Boyd emphasised in his later work.22 He highlighted the need for this flexibility across an organisation. Additionally, depending on the level of conflict (Osinga defined these levels: tactical, operational, strategic and grand strategic), the nature of how the organisation must adapt changes:23

• Tactical/Operation Level – movement, attacks, feints, etc, disrupt and confuse the enemy. The ability to adapt is defined in terms of the maintenance of your own cohesion and the reduction of the enemy’s.

• Strategic Level – the adaptation centres on adjustment of doctrine and force structures that disorient an enemy’s own orientation and understanding.

• Grand Strategic Level – a complex array of measures across all potential areas of conflict. Tempo is not as important, but the interplay of multiple lines of conflict is. Conflict revolves around the shaping of politics and society. Grand Strategy is adapted to the environment of the particular conflict.

Mental And Organisational Agility

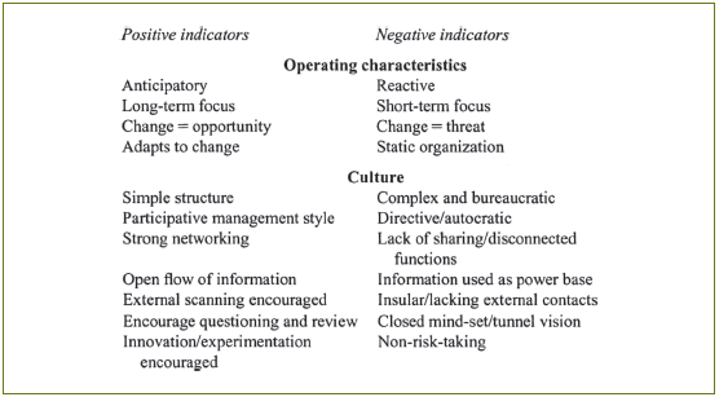

Boyd placed great emphasis on self-organisation at time of conflict. However, like the tenants of directive control, Boyd considered mechanisms (orders, restrictions and constraints) and feedback (reporting both formal and informal) essential. Boyd believed in higher commanders that could ‘trust and coach’ and were prepared to ‘accept bad news, be open for suggestions, lower level initiatives and critique’.24 To institutionalise these qualities in times of increasing strategic military and political oversight should be the challenge—a challenge that is not considered in Adaptive Campaigning. Nevertheless, such qualities, if trained for and resourced, will lead to a truly innovative military. Osinga defines the characteristic of such an organisation (based on Boyd’s own work) as:

Figure 3. Positive and negative indicators of learning organisations25

Recent work by the Harvard Business School has defined an even simpler list of characteristics to describe an ‘adaptive organisation’.26 These five characteristics are:

• Elephants in the room are named (no issue is too sensitive to be raised at an official meeting and no questions are off-limits)

• Responsibility for the organisation’s future is shared

• Independent judgment is expected, (personnel are able to comment on issues based on abilities, not just responsibility or authority)

• Leadership capacity is developed

• Reflection and continuous learning is institutionalised

The parallels with Figure 3 are obvious and a tribute to Boyd’s thought processes. Boyd always focused on military organisations. He also commenced pioneering work on the moral aspect of conflict, in particular dealing with guerrilla warfare (Figure 2); this work focused on the physical dislocation and destruction of the enemy, but the growing need for a moral framework and legitimacy in conflict is also apparent. Close associates extended this work into the debate about ‘fourth generation warfare’ after Boyd’s death.27

Discussion

Osinga credits Boyd with being the first ‘post modernist’ strategist. That I leave for others to judge and debate. A valid criticism is that Boyd unlike some (for example, Richard Simpkin28) did not work holistically, considering organisational, technical and well as cultural changes in his analysis. This he left to others. This aside, the breadth of Boyd’s work merits greater study and teaching.

Robert Polk in his 2000 critique of Boyd considers his work worthy of greater study and cites the need to use the relevant pieces of Boyd’s work in shaping future US Army doctrine.29 Lieutenant Colonel David Fadok, USAF, in his 1997 work criticises Boyd for placing too much importance on tempo in conflict. However, he still concludes that Boyd’s work is well worth further study by air power theorists and strategic planners.30 The USMC provided the honour guard at John Boyd’s funeral in 1997, and as a sign of respect the eagle, globe and anchor were buried with him.31 The Commandant of the USMC stated the he and the corps would miss their counsellor terribly. That Boyd’s work could have such widespread influence and earned respect from his colleagues confirms the merit of a more rigorous consideration of his work by the Australian Army. If we are going to use Boyd’s work though, we must use it in the right context and have a sound initial understanding.

Unlike the authors of Adaptive Campaigning, Boyd built on previous work and did not place an unproven concept at the core of any of his work. This does not mean that the Adaption Cycle’ is invalid. However, to place it centrally in our key future planning document at the expense of either version of the OODA loop does perhaps show hubris, regardless of the amount of DSTO analysis.

The importance of Adaptive Campaigning depends on its utility. It must be a document grounded in the fundamental and timeless aspects of military theory as well as preparation for the future. It needs to sell itself to the next generation of leaders. It must be easy to teach, understand and apply. In its current form, Adaptive Campaigning is not. A recent US example of an easily understandable concept is the Capstone Concept for Joint Operations. While in intent some aspects of this document do not suit Australia’s situation in terms of structure and style, it is worthy of analysis as a document that can be easily taught, understood and applied.32

Adaptive Campaigning seems to claim that the Army of the past and present does not understand the basic tenants of mission command,33 and it re-educates us with further definition. I must have been lucky with my commanders, as I served and watched other personnel thrive in the conditions Boyd highlighted. Additionally, the Adaptive Campaigning definition of mission command remains hierarchical (true mission command places emphasis on lateral synchronisation with higher commanders facilitating this) and actually places too much freedom of action with the subordinate.

The 'Adaption Cycle' And The Probing Action

It is too late to learn the technique of warfare when military operations are already in progress, especially when the enemy is an expert at it.

– General Alekse A Brusilov

The first stage of the ‘Adaption Cycle is to ‘Act’, and this is where unfortunately the entire concept becomes unhinged. The articulation of a need to test or confirm the ‘understanding of the battlespace’ immediately surrenders the initiative to an adversary. The use of probing action to enable the force to learn surrenders initiative. It exposes the force conducting the action to the risk of defeat in detail by an enemy that commits early to decisive engagement. Additionally, learning actions could have a coincidental damaging effect on future ‘decisive action’. A probing action in the wrong place at the wrong time could set a section or an entire community against a deployed force.

Such learning actions are also vulnerable to deception. If we are relying for our design of battle primarily on the initial contacts, then we again enable a cunning adversary to shape us. However, a supporter of the ‘Adaption Cycle’ would say the ‘sense’ phase would filter this out. This is again problematic without a frame of reference or prior orientation.

Against a peer competitor,34 a land force using the ‘Adaption Cycle’ as its core operating concept will surrender the initiative, risk early decisive engagement when not prepared for it, and be vulnerable to deception. The ‘Adaption Cycle’ paradoxically means that a deployed land force will behave in a rigid manner—it is a reactive concept. As both Boyd and General Brusilov alluded, we must be professionally skilled and culturally/politically aware prior to contact. While we cannot be fully oriented prior to deployment, we can achieve much beforehand.

A Way Ahead

The literature on adaptive organisations in both military and business spheres is growing. Authors range from behavioural psychologists to military personnel.35 Like Boyd, we face a myriad of viewpoints. What is apparent in the majority of literature is that, while military organisations can be extremely adaptive, they are not structured to be routinely so. Additionally, at what level do we wish to instil this trait—throughout the organisation or just into the leadership base?36 Even this can be complicated; Johnson et al states that ‘adaptive risk-taking’ in individuals may actually be a double-edged sword and engender military incompetence in battle.37 To develop a truly adaptive culture, the breadth of the military organisation needs to be considered.38 The insertion of the nine core behaviours (developed independently of Adaptive Campaigning) into the document does not remediate this conceptual gap.

Recent initiatives in the training of junior leaders in the US Army have focused on a training regime that currently serving Australian personnel would find familiar.39 The leadership base that the United States draws from is far more variable in experience and time in training. Therefore, this initiative for us is only a point of reference, not a way ahead. Additionally one of main architects of the program in previous work has cited a far broader range of initiatives;40 it is unclear if the US Army has attempted to take on these larger organisational issues.

There is acknowledgment in combat operations that the military have shown incredible flexibility. However, there is significant concern that the hierarchical structures and self-replicating personnel management practices of the military stifle adaptation. In some cases even the traditional crawl, walk, run approach to training can constrain adaptability in tactical decision-making and execution.41 One author even cites that adaptive leaders are not enough—you need adaptive teams.42 This harks back to Boyd’s preference for self-synchronisation.

The Chief of Army’s design rules within Adaptive Campaigning highlight some important adaptive tenets. However, many are self-evident necessities of any competent land force. There is no consideration of how we are to comply with these rules, or define where we are currently. No benchmark is discussed. You cannot simply have an ‘adaptive’ deployed land force in isolation. It comes from an army that itself nurtures and behaves in this way. The ten rules may even be an anathema to the principle itself.43 ‘Be adaptive, but you are to have these structures and characteristics’ An example of this tension is the drive to sustain five fixed lines of operation (rule 4); this is a big ask for an army of one division, regardless of the conflict. We may place ourselves in a paradox before we start. Organisational adaptation at all levels is required, not just small unit and individual tactics.

Organisational reform must occur that resources and supports land forces in focusing on tactical flexibility. Adaptability, like mission command, not only needs to be fostered but resourced and managed. No Army or Joint documentation defines how rapid changes are to be funded or controlled.44 Innovation and adaptation is expensive, because mistakes must be made by definition and wastage will occur; the tension with the Strategic Reform Process is obvious. We must resource the changes we see as necessary rapidly, in terms of both physical and personnel resources but also that most precious resource—time. Not in accordance with the current development rules of Army or Australian Defence Organisation, but as each new situation dictates.

The rules themselves may be a response to the certainty the government is demanding of the Department of Defence. So, creating an Adaptive Army will require the ‘whole-of-government’ support that Adaptive Campaigning lauds, but in the other direction. The search for greater and greater certainty in Defence programs lies in direct tension to what the Army is seeking. It is a concern that these higher organisational aspects of adaptation are not being considered or even acknowledged. They must be.

An example of incongruity in the drive to adaptation has already occurred within the personnel reporting process. I cite the recently implemented supplemental personnel report for 0-5 officers and above. Its assessment of that leadership group’s support of the Adaptive Army and Strategic Reform Program will not engender the behaviour traits we require.45 Institutionalising Boyd’s or Hiefetz’s adaptive organisational characteristics will.

In the application of adaptation, the Army must pick the low hanging fruit. Shifts in education and training are some of those low cost and potentially high yield first steps. Human resource management practices also have the potential to yield more adaptable units and sub-units,46 and a more balanced and better-trained staff. While the Army as a ‘learning organisation’ is highlighted in Adaptive Campaigning, the organisational reforms (and the higher command and control changes of the Adaptive Army are not reforms) required are not articulated.

Conclusion

No future warfighting concept will be perfect, nor should it be. Adaptive Campaigning not only contains significant flaws, it remains, despite numerous rewrites, difficult to read. It is also incomplete in defining what is required to make the Army truly adaptive. The solid work of the late John Boyd has been corrupted into an unproven, intuitively risky and inflexible Adaption Cycle’.

This is unfortunate because the intent behind Adaptive Campaigning is perhaps one of the boldest and strongest the Army has taken in decades. The intent has the potential to reform and reshape the Army. However, the lead document as it currently stands will not be enough. Weak concepts do not change or endanger armies when fighting conflicts of choice, but they slowly die a natural death. If faced with a conflict of necessity though, time and opportunity to develop cohesive adaptation from strong concepts may be lost, something that we can ill afford.

While some may say that current operations are forging this adaptability already, this can be a two-edged sword. Operational experience can also develop a singular focus. The Army has to make a decision as to at what level it wants to engender adaptation and how it will achieve this. Additionally, it must recognise that bureaucratic and government processes must change if Army wants to foster this throughout its structure. It is unlikely that this change can be implemented under current operational demands. Training and management systems must always provide a ‘brilliant at basics’ framework, but the student must be allowed to experiment; this will take more time and resources than the current training continuum allows. We may have to simply invest in the next generation of leaders and ask them to carry the flame.

An adaptive organisation, reading between the lines, is one that harnesses both the physical and mental abilities of all the personnel within it. The Defence catch cry of ‘people first’ is not just about support and education, it is about harnessing human capital. War is a human interaction, and Boyd was primarily about understanding how to harness this interaction and create human capital, how it operates in the stress of conflict and how to prepare it for success in that environment. Other management theorists have stated that there is no such thing as a dysfunctional organisation; any organisation produces outcomes they tolerate or with which they are comfortable. A study of Boyd forces us not to tolerate this status quo.

The ‘Adaption Cycle’ needs to be reassessed against the complete work of John Boyd. Adaptive Campaigning itself would benefit from feeling the heat of Boyd’s torch and other experts on organisational and military adaptation. A solid military concept will stand on its own merit. Those that are easy to comprehend, teach and are intellectually and intuitively sound will be enthusiastically adopted. Once this has occurred, the staff of Army Headquarters will have far less work pondering the future both near and far—the rank and file of the Army will be doing that for them. That to me is only the start of the truly Adaptive Army.

There is no absolute knowledge, and those who claim it, whether they are scientists or dogmatists, open the door to tragedy.

– J Bronowski as quoted by John Boyd47

Endnotes

1 Lexington Green, Why didn’t Boyd write a book? The John Boyd Roundtable, Nimble Books, Michigan, 2008, p. 21.

2 R Smith, The Utility of Force: The Art of War in the Modern World, Vintage Books, New York, 2008, p. xii.

3 Johnson et al, ‘Is military incompetence adaptive? An empirical test with risk-taking behavior in modern warfare’, Evolution and Human Behavior, Issue 23, 2002.

4 P G Tsouras, Changing Orders: The Evolution of the World’s Armies, 1945 to Present, Facts on File, New York, 1994, p. 152 for one example; S Peter Rosen, Innovation and the Modern Military, Winning the Next War, Cornell University Press, New York, 1994, p. 130.

5 Australian Army, Adaptive Campaigning – Army’s Future Land Operating Concept, Department of Defence, September 2009.

6 Ibid., p ii.

7 Australian Army, Complex Warfighting, Department of Defence, 2004.

8 G T Hammond, The Mind of War – John Boyd and American Security, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC, 2001, p. 118.

9 See J R Boyd, ‘Destruction and Creation’, 3 September 1976 <http://www.goalsys.com/books/documents/DESTRUCTION_AND_CREATION.pdf>; RB Polk, ‘A Critique of the Boyd Theory – Is it Relevant to the Army’, Defense Analysis, Vol. 16, No. 3, 2000, p. 272.

10 FC Spinney, ‘Genghis Boyd’, Proceedings, July 1997, Vol. 123/6/1,133.

11 For an excellent example, see A A Bazin, ‘Boyd’s OODA Loop and the Infantry Company Commander’, Infantry, January–February 2005, pp. 17–19.

12 Adaptive Campaigning, p. 31.

13 Ibid., p. 31.

14 F P B Osinga, Science, Strategy and War: The Strategic Theory of John Boyd, Routledge, Oxford, 2007, p. 231.

15 Hammond, The Mind of War – John Boyd and American Security, p. 150.

16 Osinga, Science, Strategy and War: The Strategic Theory of John Boyd, p. 172.

17 B Condell, On the German Art of War, Truppenfuhrung, 1933, Lynee Reiner, Boulder, 2001, p. 19.

18 Polk, ‘A Critique of the Boyd Theory – Is it Relevant to the Army?’, p. 271.

19 Osinga, Science, Strategy and War: The Strategic Theory of John Boyd, pp. 235–38.

20 Ibid., p. 236.

21 Ibid.

22 Boyd, ‘Destruction and Creation’, p. 1.

23 Osinga, Science, Strategy and War: The Strategic Theory of John Boyd, p. 238.

24 Ibid., p. 239.

25 Ibid., p. 82.

26 Hiefetz et al, The Practice of Adaptive Leadership: Tools and Tactics for Changing your Organization and the World, Harvard Business Press, Boston, 2009, Chapter 7.

27 Osinga, Science, Strategy and War: The Strategic Theory of John Boyd, p. 255.

28 R E Simpkin, Race to the Swift, Brasseys, London, 2000.

29 Polk, ‘A Critique of the Boyd Theory – Is it Relevant to the Army’, p. 272.

30 D S Fadok, ‘John Boyd and John Warden: Airpower’s Quest for Strategic Paralysis’ in PS Meilinger (ed), The Paths of Heaven: The Evolution of Airpower Theory, Air University Press, Maxwell, 1997, p. 389.

31 R Coram, Boyd, The Fighter Pilot who Changed the Art of War, Back Bay Books, New York, 2004.

32 US Department of Defense, Capstone Concept for Joint Operations, V3.0,15 January 2009.

33 Adaptive Campaigning, p. 36.

34 By this, I do not mean a conventional force, but an adversary, trained and equipped to an equivalent standard and equally motivated, regular or irregular.

35 K G Ross, ‘Training Adaptive Leaders: Are We Ready?’, Field Artillery, September/October 2000, p. 19; J F Schmitt and G A Klein, ‘Fighting in the Fog: Dealing with Battlefield Uncertainty’, Marine Corps Gazette, August 1996, p. 62.

36 D Jankowicz, ‘From “Learning Organisation” to “Adaptive Organisation” ‘ Management Learning, Vol.31, No. 4, December 2000, p. 471; Schmitt and Klein, ‘Fighting in the Fog: Dealing with Battlefield Uncertainty’, p. 68.

37 Johnson et al, ‘Is military incompetence adaptive? An empirical test with risk-taking behavior in modern warfare’, Evolution and Human Behavior, Issue 23, 2002, p. 261.

38 B A Brant, ‘Developing an Adaptive Leader’, Field Artillery, September/October 2000, p. 24.

39 M Padilla and D E Vandergriff, ‘Adaptive Leaders Methodology (Applied)’, TRADOC presentation, 11 December 2007.

40 D E Vandergriff, Raising the Bar, Center for Defense Information, Washington DC, November 2006.

41 G Klein and L Pierce, ‘Adaptive Teams’, 6th International Command and Control Research and Technology Symposium, Annapolis, June 2001.

42 Ibid., p. 2.

43 Adaptive Campaigning, p. 64.

44 Including the Adaptive Army initiative.

45 S Kerr, On the folly of rewarding A, while hoping for B, The Academy of Management Executive, February 1995, p. 8.

46 E D Pulakos et al, ‘Adaptability in the Workplace: Selecting an Adaptive Workforce’ in C Shawn Burke, Linda G Pierce, Eduardo Salas (eds), Understanding Adaptability: A Prerequisite for Effective Performance within Complex Environments – Vol. 6 of the book series: Advances in Human Performance and Cognitive Engineering Research 2006, p. 64.

47 J Bronowski as quoted by John Boyd in Osinga, Science, Strategy and War, p. 274.