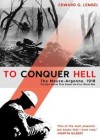

To Conquer Hell: The Meuse-Argonne, 1918

Written by: Edward G Lengel,

Henry Holt and Company, New York, 2008, 512 pp.

Reviewed by: Dr Douglas V Johnson II

Ed Lengel has gathered together a large collection of first person accounts of this campaign and has woven them together with just enough context to produce a ‘nice’ piece of fabric. I say ‘nice’ because this fabric is basically gray in background, but splotched from top to bottom with battlefield detitrus, and the offal of human remains. If the intent is to convey the horror of combat, well done! If the intent is to convey a larger lesson it is somewhat obscured by the miasma of combat in the Meuse-Argonne.

I developed mixed feelings as I began reading this book. At first I was taken by the observations that this battle is largely unknown to the American public—as is the First World War—but then I reflected that it was very far from true for the interested reading public thanks in large measure to Robert H Ferrell. Ferrell wrote America’s Deadliest Battle: Meuse-Argonne, 1918 in 2007; Collapse at Meuse-Argonne: The Failure of the Missouri-Kansas Division in 2004; as editor, he treated us to William S Triplet’s spectacular memoir, A Youth in the Meuse-Argonne: A Memoir, 1917–1918 in 2000; and to Major General William M Wright’s diary, Meuse-Argonne Diary: A Division Commander in World War I in 2004. Then there is Alan Gaff’s Blood in the Argonne: The ‘Lost Battalion’ of World War I in 2005. And of course the late Paul F Braim’s The Test of Battle: The American Expeditionary Forces in the Meuse-Argonne Campaign from 1989. All that said, the general public is as ignorant of the existence of the First World War as they are of many things in history. In my own experience, editors insist that writers on the subject must first introduce readers to that war and how we came to be involved in it. In the process of fulfilling this mandatory requirement one must skim lightly over a great deal of material to get on with the primary task, then fulfill the intermediate task of explaining what this American army looked like and how it came to be. Lengel has done both in nicely readable style. At page 85 we arrive at Part III, 26 September 1918.

As a field artilleryman I choked on what I considered the glib description of the opening barrage; then I had the opportunity to once again curse the publisher who placed a V Corps map in the middle of a description of III Corps action and did so without a meaningful label or dates. None of the maps have dates.

Next I stumbled over phrases like this: ‘Colonel John H Parker ... had never seen a stronger line nor one more stubbornly held’, followed immediately by ‘His ... men swept forward with hardly a delay ... driving the Prussian Guards in front of them like a flock of sheep ...’. I am confused. How tough was it? Again, poor editing.

By the time we arrive at the 35th Division things begin to jell and the picture painted of that division is nicely done as Lengel portrays the progressive collapse of the chain of command. The National Guard officers of that division had been damned in several Inspector General Reports before the division ever left the United States, but the substitution of Regulars for the ineffective National Guard officers on the eve of entering combat seems to have done a lot more harm than good. Triplet has some interesting observations on that subject. Lengel’s portrayal of the process of the division’s collapse is compelling.

Thereafter one is remorselessly subjected to one wretched portrayal after another of the miserable life of an infantry soldier—the particular battle or even war matters little.

Almost every unit action description falls into the same pattern: the soldiers are exhausted by the preceding day’s events; in response to ill-conceived demands of their ignorant superiors, they move forward through the morning fog until either the fog lifts or the Germans detect them; they are then set upon from front and both flanks by masses of machine guns artillery in direct fire as well as barrage fire—every advance seems to be into a fire-trap, and always snipers. It seems that every German soldier must be a sniper because that is all one reads about. There is seldom any supporting artillery fire and that part of the story is essentially correct. So too is the debunking of Billy Mitchell’s boasting of his support to the troops—American aircraft do not appear over this battlefield anymore than they did over Soissons save for the first few hours of the first day.

At this point I had to pause to reflect on Dave Glantz’s rejoinder to criticism of several recent works on Stalingrad for becoming too mired in detail after detail. Glantz’s position is that ‘accurate detail is the only basis for sound judgment in all other matters ... Lack of this detail renders all such judgments unfounded and of dubious validity’.1 I understand that, but have to wonder how much detail is required to make a point? What keeps me moving on is Lengel’s delightful interjection of vignettes, of moments of heroics, moments of inspiration. In fact, toward the latter third of the book he begins to demonstrate a key theme in Mark Grotelueschen’s fine analysis of The AEF Way of War: The American Army and Combat in World War I. Grotelueschen posits innovation and imagination growing out of the frightful stupidities and inexperience of the early days of combat. Lengel illustrates this development with cases in which lower unit leaders simply chose novel ways to interpret the command. ‘Continue the attack!’

I would like to have seen some of the German soldier’s-eye view. The German Army level command speaks, but not the German soldier.

To Lengel’s credit, he has placed a thin veneer of larger context atop this tale of blood, gore and destruction. Periodically, like the tired infantrymen whose story he is telling, he pauses to pull the disparate threads together, enough to let the reader see a bit more of the picture. But here I must pause again to curse the editors for failing miserably to support a very complex story with adequate maps. Ground combat is about maps. The stories make little or no sense without them. They are plentiful and they are free.

The definitive book on this campaign is yet to be written, but this one will help whoever undertakes that task.

Endnote

1 David M Glantz, ‘Stalingrad Revisited’, The Journal of Military History, Vol. 72, No. 3, July 2008, pp. 907–10.