The interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq have highlighted the difficulties in building a sustainable peace and a conceptual and institutional ‘gap’ in the UK’s peacebuilding capabilities. Consequently, both operations have witnessed the introduction of new approaches to managing stability operations. Whilst these are unlikely to resolve the broader strategic challenges, they represent a range of useful developments in the delivery of a ‘stabilisation’ effect.

The core ideas are the focus on ‘stabilisation’ as an activity that takes place within a different framework of priorities from either ‘development’ or ‘hearts and minds’ activities. The paper also argues for a sharpening and to some extent a returning to basics for military CIMIC whilst also recognising that ‘operational CIMIC’ requires the Ministry of Defence to ‘up its game’. It also highlights the need for new and predictable institutions that enhance the capacity for comprehensive and integrated (rather than sequential or co-ordinated) interdepartmental planning whilst also stressing the difficulties with stabilisation models that imply a generic sequencing of activities rather than approaches that represent a mixture of simultaneity and critical path analysis.

Perhaps the most significant of these has been the introduction of the ‘Provincial Reconstruction Team’ (PRT) concept. Whilst originally a US innovation, the UK has made significant adaptations and currently runs two, one each in Afghanistan (Lashkargar) and Iraq (Basra).1 PRTs do not come with a fixed structure; rather they comprise mixed military and civilian staff from a range of Government departments (principally the Foreign Office and Department for International Development) and are charged with organising and delivering ‘reconstruction’ and ‘development’. Whilst they offer a range of benefits, they have also been plagued by controversy and criticism. Nevertheless, this paper argues that whilst they appear to be an ‘inevitable’ feature of the operational environment there is a requirement to situate them within a more considered doctrinal and institutional framework.

Origins and Issues

The PRT concept was originally a US initiative, developed in Afghanistan in late 2002 and employed initially as part of Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF). They were intended as vehicles for kick-starting the stalled development process and building consent in areas where US combat forces operated. The original label, ‘Joint Regional Teams’ was changed at the behest of the Afghan President, Mohammed Karzai, who inserted ‘Provincial’ in order to emphasise their role in coordinating and contributing to donor and military support to the Afghan regions. However, and critically, their roles and organisational structures were never defined with any degree of precision.2

Subsequently several NATO states adopted PRTs as a part of their contribution to the UN authorised International Security and Assistance Force (ISAF) mission. Their utility was essentially political, providing a mechanism for reconciling visible support to NATO and, to a lesser extent, to the United States, with an absence of political will to deploy conventional troops in a combat role. In a more practical sense PRTs also offered a means for stimulating development work in contexts where insecurity was so profound that civilian development agencies were unable to function. Subsequently, the concept was extended to Iraq in a belated attempt to invigorate the stalling reconstruction programme, generate economic activity, build Iraqi provincial government capacity and extend the rule of law.

The PRT concept was controversial from the outset.3 At their unveiling, US military commanders appeared to imply a hegemonic military role in the co-ordination of humanitarian NGO work; implicitly threatening to usurp the UN’s coordination role whilst symbolising the unwillingness of NATO states to provide sufficient numbers of combat troops. Humanitarian organisations also raised a range of practical concerns; arguing that the military did development work poorly, that this represented a diversion from their primary security provision role and that their presence contributed to a blurring of the lines between military and humanitarian actors that potentially threatened the lives of aid workers. The supposed ineffectiveness of military led reconstruction was also cited as having the potential to create destabilising social tensions amongst beneficiary communities that raised the possibility of undermining ‘stabilisation’ through the very instrument created to achieve it.

The functional and organisational diversity that characterised the OEF and ISAF PRTs exacerbated many of these controversies.4 Whilst NATO states frequently justified the organisational variation and their refusal to be prescriptive as a reflection of the very different local conditions in which PRTs operated, many critics were suspicious that this was a ruse for justifying both national agendas and the absence of an effective strategic framework in which the PRTs could function. Furthermore, there was a sense that the variation in structure, funding, purpose and the tenuous linkages with Afghan development priorities appeared to reflect and amplify, rather than reduce the dysfunctional forms of coordination that plagued relationships between the Afghan government and donor states.5

The label ‘Provincial Reconstruction Team’ also created confusion within Governments. For some, and quite understandably, the phrase conjured visions of an organisation that provided a hub for project managing ‘physical’ reconstruction. Others welcomed the mechanism as a means for simplifying the ‘civilian’ aspects of the battlefield, creating a ‘one stop shop’ for the delivery of ‘civilian lines of operation.’ Even the use of words such as ‘Provincial’ and ‘Reconstruction’ muddied the waters, encouraging the sense of PRTs as tactical level instruments for consent building rather than vehicles for bringing together (often) national civilian and military instruments in order to build a sustainable local capacity to govern.

Confusion, some understandable, some pedantic, also arose from the range of apparently similar structures that could be described as PRTs. How, for example, did one differentiate a PRT from any of the other headquarters structures that combined support from Defence and Civilian Ministries? Did the provision of military staff officers through the Coalition Provisional Authorities’ Governorate Support Teams in 2004 create de facto PRTs? Would, the arrival of DFID and FCO officials in any military headquarters make this into a PRT?

Such definitional challenges translated into difficulties in locating PRTs within the intervening states own ‘organisational’ and ‘institutional’ hierarchies (felt in terms of difficulties in defining organisational jurisdictions, levels of autonomy, capacity to shape policy and operational responses, etc) and in defining their role with respect to host nation Government’s regional development priorities. This generated a range of practical questions related to issues of ‘transition’. How and by what process, for example, should capacity within the PRT transfer to a suitable host nation provincial structure? Should PRTs begin as largely military structures, becoming increasingly dominated by civilian officials from the intervening state before transitioning to staff appointed by the host nation itself—in effect PRTs remaining in existence but as host nation structures? Alternatively, should PRTs progressively transfer their own capacity directly to host nation regional development and governance structures (such as Provincial Reconstruction and Development Committees); effectively withering away as local or provincial capacities grew? Similarly, and related more to Iraq than to Afghanistan, what should be the relationship between the transfer of security responsibilities to host nation control and the evolution of the PRT structures? Should PRTs, for example, remain in existence as a form of ‘operational’ or ‘strategic’ over-watch when Iraqi provinces are granted ‘Provincial Iraqi Control’—perhaps even remaining in circumstances where the Iraqis themselves have the capacity to replicate PRT development capacity? Such questions continue to invite policy makers to more clearly define the purpose, organisation and function of PRTs.

Conceptual Gaps?

The use of PRTs reflected the limits of existing tools, both military and civilian, for managing the problems of ‘stabilisation.’ Increasingly, neither military led ‘Civil-Military Cooperation’ (or CIMIC) nor traditional civilian ‘development’ instruments had proven to be adequate instruments.

Historically, ‘CIMIC’ had focused on maximising the Commander’s freedom of manoeuvre through ‘liaison’ and a range of consent building or ‘hearts and minds’ activities. It served as an ‘observation post’ on the civil community; warning commanders of limitations or threats that derived from the civilian population and, wherever possible, mitigating them. As such CIMIC was a limited instrument that focused on the tactical level mission. But, CIMIC staff, steeped in the military ‘will do’ culture and pressured into dealing with all aspects of the civilian environment by the need ‘to do’ something were frequently unsure of the boundaries of their own role and slowly drifted into either humanitarian work or the management of more complex issues such as local government or economic reform.

However, as the demands placed upon, and the requirements for greater expertise on the part of, CIMIC troops increased, the wider Army clung to the mistaken belief, derived from a misreading of its own experiences in Malaya and Aden and reinforced by its Peace Support doctrine, that CIMIC did not require any particular knowledge. Rather there was a widespread sense that everyone could ‘do’ CIMIC. They were not wholly mistaken in this—but only if you defined CIMIC in a particular way, basing it around a very limited form of ‘friendly interaction’ with the civil population designed to build a sense of legitimacy for the military presence. Experiences in theatres as diverse as Malaya, Aden and Northern Ireland appeared to teach that such interaction was crucial and did not require any particular expertise. However, increasingly CIMIC troops were not being tasked to manage this simple interaction and ‘bottom up’, military led ‘hearts and minds’ activities did not equate either to a ‘stabilisation’ or ‘state building’ strategy and failed to systematically develop the legitimacy and capacities of local administrative structures linked to national political and development priorities. Furthermore, when the military did engage in more sophisticated ‘hearts and minds’ programmes linked to ‘capacity building’ objectives they were frequently criticised for failing to sustainably link these with longer term development objectives. Consequently, the tactical level, piecemeal, ad hoc and traditional form of CIMIC have increasingly proven insufficient for dealing with the challenges that Iraq and Afghanistan have generated.

However, the problems with CIMIC have been paralleled in ‘development’ circles. During the summer of 2006, DFID’s activities in Afghanistan were criticised for failing to demonstrate that the UK military’s arrival in Helmand was linked to immediate and tangible development benefits. In part this arose from a perception that DFID’s longer term development approach did not provide the type of ‘quick win’ that military commanders and politicians demanded. The causes of this problem were difficult to identify. Some within the UK military argued that they believed DFID’s priorities were too strongly shaped by a culture of long term development, free of the immediate demand for political effect and overly constrained by security concerns. However, whilst problems undoubtedly existed, the scale was often exaggerated and DFID staff were increasingly aware both of the need to rapidly implement projects and to link these to local ‘political’ effects within the context of a ‘stabilisation plan.’ Quick Impact Project (QIP) money flowed in the autumn, managed by a PCRU project manager, and facilitated by DFID’s own financial gymnastics, placing money within the framework of the Global Conflict Prevention Pool in order to bypass the spending restrictions derived from the International Development Act.

An Emerging Gap?

These controversies highlighted the powerful pressures to achieve demonstrable ‘stabilisation’ effects through QIP projects as well as the unreality of expectations as to what could be achieved and in what time frame. They also hinted at an underlying conceptual ‘gap’ between traditional development strategies and the military led ‘hearts and minds’ or ‘consent’ winning work. Arguably, what is required to fill this is a new ‘stabilisation’ strategy that differs in its priorities and principles from both traditional ‘development’ and ‘hearts and minds’ approaches; being more ambitious and timely than the former and more ‘political’ than the latter. Such an approach would require a mix—quick impact projects, political engagement with and the empowerment of moderate actors, outreach to isolated communities, programmes to resuscitate and extend key institutions and essential services—in effect the employment of instruments that focus on creating a space which is conducive to the emergence of moderate voices given the capacities to manufacture a stable and sustainable peace. Whilst many of these instruments are not new, there is a pressing need to improve the way in which government departments collectively wield them.

Possible Structures?

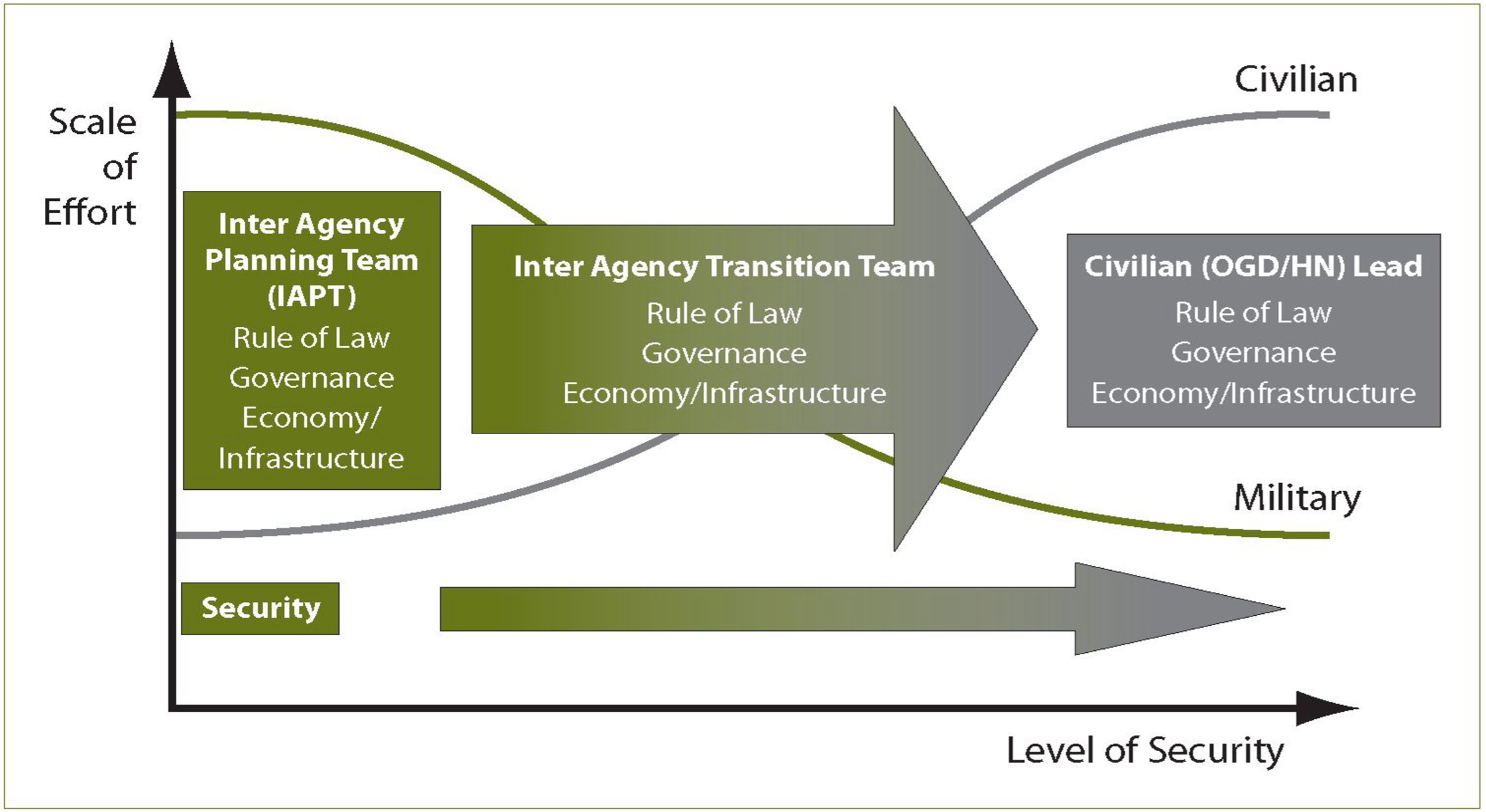

A new ‘stabilisation’ strategy obviously requires considerable interaction between government departments prior to and during the deployment of troops. However, whilst a ‘comprehensive’ plan can be prepared before the deployment of military forces, the security situation may prevent civilian officials from delivering their part (at least initially) in theatre. Hence there will almost certainly be an increased reliance on the military, particularly in the short term. In such cases there is a danger that the original plan will not be delivered by its authors and will be granted a much lower priority than the military commanders’ immediate military objectives. In order to avoid the distortions that this inevitably introduces there is a need for some type of interdepartmental and operational level co-ordination structure that can take ownership of, implement and develop the initial plan. Finally, as a part of the exit strategy, there needs to be a two part handover from the (probably) largely military led structures to other civilian government departments and then to sustainable host nation institutions. Posing the problem in this way allows one to identify the necessity for three stages of stability planning (pre operational, operational and disengagement) and two generic structures for its management.

Arguably the first of these is an operational level, (largely) national planning structure that can bring together the FCO, MOD, DFID and Post Conflict Reconstruction Unit (PCRU) in the pre-deployment phase in order to develop an interdepartmental or ‘comprehensive’ plan that will shape subsequent departmental planning. A similar structure, an ‘Inter Agency Planning Team’ or IAPT, was employed in autumn 2005 prior to the extension of the British presence into Helmand province. Such a planning capability would need to be owned directly by the Cabinet Office and able to impose its authority, challenge departments that develop plans that undermine the ‘comprehensive plan’ or fail to balance adequately the ‘stabilisation’ and their individual ‘departmental’ objectives.

Ideally the resulting plan would be handed on to a second structure: an operational level, national interdepartmental planning and stabilisation ‘delivery’ structure that operates through the ‘deployment’ and ‘operational’ phases. This could be labelled an ‘Inter Agency Transition Team’ (or IATT) but in effect it would do what the PRTs do. In situations of chronic insecurity this could initially be established within the senior military formation deployed, as a part of the J5 branch, but also drawing on the capabilities frequently found in the C/J/G9 and staffed by an interdepartmental civil-military team. This structure would be located at the level of the most senior national military headquarters deployed to the theatre, but would separate and ‘civilianise’ as soon as the situation permitted. Again the intention would be to create a structure that was able to ‘manage’ and husband an interdepartmental ‘stabilisation’ plan rather than implement the implied civilian tasks that support an essentially ‘military’ plan. Hence, the IATT structure, embedded initially within the military planning branch, would need to report back to a structure in Whitehall that could provide it with sufficient ‘bureaucratic space’ and authority to ensure its capacity to maintain the ‘interdepartmental’ nature of the stabilisation plan whilst remaining sufficiently ‘connected’ to the military to ensure that it remains relevant to the operational situation. The IATT should therefore remain as a planning and co-ordination tool rather than a vehicle for implementing reconstruction tasks delegated by a military commander.

Thirdly there is a need to create sustainable host nation structures prior to and after the withdrawal of international troops, and their creation is largely beyond the British Government’s remit to dictate.

Justifying the IATT Concept?

Superficially the IATT concept may appear to be a simple re-branding of the PRT but it does have the potential to deliver a fundamental change in the way in which states’ manage ‘stabilisation operations.’ Within Ministries of Defence traditional approaches to crises have tended to characterise civilian government departments as initially supporting a defence ministry and only gradually shifting into the lead as the security situation improves. In this role they also leverage international organisations and NGOs. The ‘sequential’ nature of the model implies that the creation of a ‘secure environment’ will precede all other stabilisation and state building activities both in timing and its significance within the strategic plan. This model has a number of flaws: firstly ‘security’ is not the most important planning factor in the development of the strategic plan; secondly intervention strategies cannot be planned according to an essentially linear model, and thirdly, planning processes and organisations need to stress the identification of ‘critical paths’ and iterative approaches to planning.

In terms of the former, whilst security is a priority, it is one of several and is often compromised by the pursuit of political objectives that are externally imposed. The mass sacking of the Iraqi Army, the prioritisation of the reform of the Afghan National Army over that of the Police, the low numbers of international troops deployed in both Afghanistan and Iraq are good examples of external political settlements that are largely unrelated to the prioritisation of the security strand within a stabilisation plan.

Secondly, military campaign planning tends to envision parallel and broadly sequential ‘lines of activity.’ This approach does not always recognise sufficiently that all lines of operation are not immediately possible, that many are contingent on a range of other, often unrelated, occurrences, and that some actions will have devastating and unintended consequences for others. Clearly ‘multifunctional’ interventions encompass activities that cause changes within a wide range of political, tribal, social, economic and security systems—changes affecting one of these frequently cannot be understood in isolation from changes in the others. Such an analysis implies a need for an operational level strategy co-ordination mechanism that is able to move beyond the delivery of reconstruction ‘services’ and identify, reflect upon and manage the complex (often political) interaction between the differing lines of national and international ‘stabilisation’ activity as well as the consequences of externally imposed political constraints and processes—that is, it is able to manage critical paths.

However, the argument for an ‘Inter Agency Transition Team’ does not equate either to a justification of the PRT concept, nor does it imply the ‘militarisation’ of stabilisation planning and delivery. Rather it is related to ensuring that government departments have a predictable institutional mechanism for engaging in the day to day and operational setting of priorities within a framework that is genuinely interdepartmental yet potentially flexible enough to incorporate coalition and other partners.

Activities and Ownership

After having established a case for thinking about interventions differently, the issue then becomes one of defining what the IAPTs and IATTs do. Ideally the IAPT would create an interdepartmental framework plan in which the separate ministries would frame their own responses. The IATT would deploy alongside the military intervention force, inheriting the plan developed by the IAPT as well as several of the key staff that had initially formulated the plan. As a staff, perhaps headed by or reporting directly to some form of special government representative (ideally the senior British official in theatre, such as the UK Ambassador) it would become the first custodian of the ‘stability’ plan. The IATT could also become the principal vehicle for delivering (that is identifying need, determining funding, linking implementation and donor agencies) projects that go beyond military ‘hearts and minds’ and ‘population control’ type activities but fall well short of traditional development activity. This approach would result in a range of benefits not least of which would be to bring coherence between tactical, military delivered ‘consent winning’ activities, much longer term ‘development’ strategies and the more significant operational level ‘stability’ type activities. It would also enable the IATT to better resist pressure to deliver short term consent building projects (paint that school!) rather than stabilisation activities (initial governance, ‘first stage’ Security Sector Reform, etc). Similarly it has the potential to provide a framework that would enable ‘hearts and minds’ and development activities to contribute more coherently to stabilisation priorities, without undermining either, and taking place within an overarching information campaign that can leverage the political benefits.

In practical terms the IATT should be owned by the PCRU but would be staffed by a mixed military and civilian (FCO, DFID, Home Office, PCRU and MOD civilian) staff, the military predominating in the early stages of the crisis but the composition moving to favour the civilian component as the security situation improved. Initially it would almost certainly have to be physically located within the senior military HQ for ‘life support’ reasons6 but also reflecting the simple reality that it needs to be a part of a mechanism that can influence the operational level military decision making. It would be separated as soon as possible from this military headquarters in order to create a sense of progress and of the civilianisation of the campaign as well as maintaining its role as the principal mechanism for coordinating and delivering stabilisation effects on behalf of a range of Government departments. At no point would it be subordinate to any military headquarters, but its relative importance would change over time as the campaign evolved and became less focused on ‘hard’ security and more focused on stabilisation and development.

More Capacity Building, Less Reconstruction

The IATT arrangement would differ from the PRT approach in the sense that it is envisaged as being a more ‘strategic’ tool for the co-ordination of (largely) national stabilisation and development capabilities—and far more resistant to pressures that transform PRTs into reconstruction management vehicles. In a sense it is not without recent precedents. In Iraq the Southern Iraq Steering Group and, in Afghanistan, the Helmand Executive Group drew together the key planners and decision makers whilst having access to PRTs that served as a secretariat as well as coordinating the delivery of stabilisation effects (rather than short-term reconstruction). The IATT also echoes the historical experiences of the Malayan counter insurgency campaign, paralleling the Briggs’ plan’s reorganisation of the colonial Malay states’ capacity to combat the communist insurgency. This established largely police and civilian-led mechanisms for directing and coordinating the entire war effort through linked civil-military executive committees at federal, state and district levels. These structures resulted in a far more cohesive effort, drawing together the hard security and intelligence plans (plans for patrols, ambushes, intelligence gathering) with punitive elements (population and food control) and development, largely under the direction of a series of regional and ultimately national war executive committees.7

Additional Adaptations

The MOD should also rethink its approach to delivering its CIMIC capability. However, the key questions are also almost certainly the most basic—what is CIMIC, who does it and how is it managed? In terms of the former, many of the basic definitions work already, in particular the NATO and UK definitions8 conceive of CIMIC as essentially a support function for the military commander. The key change is to separate the broader operational planning and stabilisation CIMIC function from the tactical CIMIC function, but without losing either or separating them so completely that they lose synergy. In effect CIMIC requires doctrine and capabilities for its two emerging branches—traditional or ‘tactical CIMIC’ and ‘stabilisation CIMIC.’

Who does this is more challenging. Tactical CIMIC, defined in this way is every soldier’s responsibility, but experience shows that within the commander’s staff it is managed most effectively by individuals with specialist training and who are located within the ‘Operations Support’ (C/J/G3) staff branch for ‘delivery’ and within the planning branch (C/J/G5) to ensure inclusion in longer terms ‘plans’. The delivery of projects (when appropriate for the military to do so) is best performed by whomsoever has a clearly defined comparative advantage, but the management of the projects and the co-ordination of the military implementation of the overall plan needs to be dealt with in the operations branch (C/J/G3). The purpose underlying this arrangement is to firmly situate tactical CIMIC as a part of the Commander’s ‘non-kinetic’ armoury alongside information operations, psychological operations and within an information campaign that seeks to deliver consent and minimise civil interference within a broader stabilisation plan formulated and husbanded at higher levels by the IATT.

Meanwhile, ‘stabilisation CIMIC’ would orientate itself to initially supporting the work of the IAPT and its subsequent transition to an IATT. In this role it provides a transition mechanism that seeks to promote and protect the IAPT plan during the period in which governmental civilian staff may be absent from the operational theatre and military planning structures and more insular forms of military logic may be hegemonic. In effect, ‘stabilisation CIMIC’ staffs function as interlocutors between the MOD and other government departments, not in the sense of providing an external strategic ‘liaison’ mechanism but through acting as custodians of and advocates for the broader components of the IAPT plan within a military headquarters. Their purpose is to champion the ‘implications’ of the IAPT plan during the military planning process whilst also seeking to create the conditions necessary to effect a transition to civilian and more importantly to host nation control of the stabilisation plan. Whilst transition may be one of the principles guiding their activities they should also pursue more tangible objectives. In particular, within the framework of the IAPT plan operational CIMIC should seek to change the conflict dynamic through creating an environment in which moderate voices can flourish and populate legitimate institutions that deliver effective and appropriate public services. Stabilisation CIMIC is unashamedly a political conflict resolution strategy.

The second part of ‘who does it’ is the issue of augmentees. The overwhelming majority of commissioned and non-commissioned officers involved in CIMIC in the past 4 years have been augmentees with little or no training. Even where individuals from the UK’s Joint CIMIC Group are present, the marked differences in the way in which formations organise CIMIC make it difficult to apply best practice. In addition to formalising CIMIC as an Operations Support staff function there is a requirement for a more clearly defined stabilisation CIMIC sub-specialisation and a deepening of the training provided. Defence needs to recognise that CIMIC, however defined, has generally not been performed well and requires more effective investment.

Endnotes

1 The latter as part of the initial US State Department plan to create PRTs in each of the Iraqi provinces.

2 For a useful discussion of the development of the PRT concept see B Stapleton, ‘The Provincial Reconstruction Team Plan in Afghanistan: A New Direction?’ Bonn, May 2003 (authors’ copy); see also Peter Viggo Jakobsen, ‘PRTs in Afghanistan: Successful but not sufficient’ Danish Institute for International Studies Copenhagen 2005:6 at http://diis.dk/sw11230.asp

3 See PV Jakobsen, Op.Cit.

4 See S Gordon, ‘The Changing Role of the Military in Assistance Strategies’ in A Harmer and V Wheeler (Eds), Resetting the Rules of Engagement, HPG Report 21, Overseas Development Institute, March 2006. See also See Peter Viggo Jakobsen, Op.Cit.

5 Ashraf Ghani and Claire Lockhart, ‘State Building as an Answer to Global Insecurities: Europe’s Ro’’ unpublished mimeo.

6 It would almost certainly be dependent on the military headquarters for intelligence, information support, accommodation and force protection.

7 For coverage of the administrative arrangements see Anthony Short, ‘Communist Insurrection in Malaya (London: Muller, 1975 pp. 378–85); John Coates, ‘Suppressing Insurgency: An Analysis of the Malayan Emergency, 1948–1954 (Boulder, Colo: Westview Press, 1992) pp. 116–119; Richard Stubbs, ‘Hearts and Minds in Guerilla Warfare: The Malayan Emergency, 1948–1960 (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1989) pp. 98–101.

8 The NATO definition is ‘The coordination and co-operation, in support of the mission, between the [NATO] Commander and civil populations, including national and local authorities, as well as international, national and non-governmental organisations and agencies.’ Ratified in MC 411/1 ‘NATO Military Policy on CIMIC.’ See also AAP-6 ‘NATO Glossary of Terms and Definitions’ and UK Joint Warfare Publication 0-01.1 ‘UK Glossary of Joint and Multinational Terms and Definitions’. The UK MOD defines CIMIC as ‘a function of operations conducted to allow the Commander to interact effectively with the civil environment in the Joint Operations Area (JOA). It provides for co-operation, co-ordination, mutual support, joint planning and information exchange between military forces and in-theatre civil actors. It thereby assists the Joint Task Force Commander (JTFC) with the achievement of the military mission and maximises the effectiveness of the military contribution to the overall mission.’ UK Joint Doctrine Publication 3-90, para 108.