Abstract

This article outlines three separate critiques of the Australian Army’s new Adaptive Campaigning concept. The author argues that both the ‘Adaptive Action’ and ‘Adaption Cycle’ elements of the new concept are superfluous given that other sound concepts like JMAP and the OODA loop already exist. The author also takes exception with the Joint Land Combat vision, which he perceives as being ‘inwardly focused and process driven’, and which he maintains too readily cedes the initiative to the enemy.

The common soldier wears the dress of the country; with his gun he is a soldier; by hiding it and walking quietly down the road, sitting down by the nearest house, or going to work in the nearest field, he becomes an ‘amigo’, full of good will and false information for any of our men who may meet him.

- US Army Brigadier General James Wade

Philippines, August 19011

Introduction

Former US Marine Corps Commandant, General Charles C Krulak describes it as the ‘stepchild of Chechnya’. General Rupert Smith calls it ‘war amongst the people’. Current Australian doctrine has applied the label ‘complex warfighting’. All three terms describe the current battlefield as diffuse, lethal, timeless and complex. It is broadcast into millions of homes around the globe by CNN, BBC and YouTube and represents a change in the types of wars for which Western armies have traditionally trained and been equipped. However, this condition does not mean that complex warfighting is entirely new. There are countless examples of past conflicts that exhibited some or most of the characteristics described above. For this reason we must be wary of any impulses to introduce multiple new concepts in our development of capability, training and doctrine to fight the ‘new’ war. While new concepts may be necessary, sometimes all that is required is to look at proven concepts in a new light.

Adaptive Campaigning is the response to the Australian Army’s Future Land Operating Concept (FLOC), Complex Warfighting. While the document as a whole adds constructive detail to the discussion started in the FLOC, there are concepts presented that need to be replaced or modified. Using three of the four components of the command and control continuum of planning, decision-making, execution and assessment (PDE&A), this article will critically examine the concepts of ‘Adaptive Action’, the Adaption Cycle, and the Joint Land Combat response to ‘fighting for, and not necessarily with’ information.2 I will offer a perspective on these concepts based on US Marine Corps doctrine, personal research and personal opinion. I will also link the planning processes to implicit decision-making and high tempo execution through the Joint Military Appreciation Process (JMAP), the Boyd cycle and the Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory’s ‘Combat Hunter’ experiment. Underlying threads of shared situational awareness, mental models, orientation and initiative will be common throughout each section.

Planning and Adaptive Action

The concept of Adaptive Action is proposed as an alternate approach to land operations in the complex environment. It is an ‘iterative process that combines the process of discovery (the problem is ‘unknowable’ until we prod it) and learning’.3 In this context, the land force will act first to stimulate a response, sense to observe and interpret reactions, decide on when and how to adapt, and adapt based on changes in the adversary and the environment.

There are several flaws to the concept of Adaptive Action and its manifestation in the Adaption Cycle. Most glaringly is that act precedes all other steps, implying action without planning. This may not be intentional and is somewhat at odds with the actual description of Adaptive Action and will be covered in more detail in the next section. The argument for the need for the Adaptive Action process states:

Traditionally the Land Force has conducted deliberate planning with the aim of arriving at a solution prior to interacting with a problem. This approach is based on the belief that the more time spent planning prior to an operation the greater the likelihood of success. Unfortunately, this process fails to account for the complexities and adaptive nature of the environment.4

There are three inaccuracies in this argument: that the ‘solution’ is the aim of the planning process, that deliberate planning fails to account for the complex environment, and that deliberate planning does not provide interaction with a problem.

The first two inaccuracies are related. First, the aim of deliberate planning is not to generate a solution; the solution is the least important output of any planning process. Second, a planning process cannot fail to account for complexity; it is the planners that make this mistake. Marine Corps Doctrine Publication (MCDP) 5 Planning lists the four key functions of the planning process as directing and coordinating action, generating expectations of how actions will evolve, developing shared situational awareness, and supporting the exercise of initiative.5 There is no mention of a solution. The latter two listed functions may be of the most value in the complex battlespace. Colonel Clarke Lethin, Assistant Chief-of-Staff (Operations and Training) for the 1st Marine Division (MarDiv) during Operation IRAQI FREEDOM found that the Marine Corps Planning Process (MCPP) placed ‘everyone on the same playing field, providing a common point of departure and set of procedures’.6 For 1st MarDiv planners, the shared situational awareness brought about through deliberate planning provided for adaptation and initiative in execution. This experience shows the true value of shared situational awareness in generating desired emergent behaviours that are manifest in battlefield initiative. Emergence and emergent behaviours are key components of complex systems theory. The beneficial emergent behaviours of synergy, adaptability and opportunism will develop the self-synchronisation that is vital to the ‘swarming’ concept outlined in the Joint Land Combat section of Adaptive Campaigning.7

Deliberate planning is the process that develops shared situational awareness and enables desired emergent behaviour on the battlefield. These outputs are much more important than a solution.

The assertion that traditional planning does not provide interaction with the problem is false. Deliberate planning is interacting with the problem. From mission analysis to wargaming, manoeuvre warfare emphasises planning as a continuous learning and adapting process, not a means to write a script. The reality is that military operations have always had an adaptive nature and have always been learning environments that require interaction with the problem in a planning process. From Sun Tzu: ‘Thus, one able to gain the victory by modifying his tactics in accordance with the enemy situation may be said to be divine’.8 Scharnhorst believed that ‘in the field the officer must almost constantly discover, compare, and select the appropriate means’, and in his opinion the successful general ‘initiated his campaign with a pre-meditated plan that contained many contingencies, each corresponding to a hypothesis he had made about the enemy’s probable and possible intentions’.9 This was written into Marine Corps doctrine as recently as the mid-1990s: ‘War is an even more complex phenomenon—our complex system interacting with the enemy’s complex system in a fiercely competitive way’.10

Where does this leave the concept of Adaptive Action? As a new but unnecessary concept, it is confusing and should be removed from Adaptive Campaigning. The Joint Military Appreciation Process (JMAP) already provides what Adaptive Action promises: ‘a means to arriving at a start point with a mental model of the problem and how it is likely to adapt’.11 The JMAP does need to be updated with information from the Population Protection, Population Support, Public Information and Indigenous Capacity Building lines of operation presented in Adaptive Campaigning. This will provide planners a different prism through which to view the JMAP and will provide a better means of planning in an inter-agency environment. The Australian Army and the Australian Defence Force are not the only organisations facing this problem as there is also a recognised need to update the MCPP to reflect the application of non-military elements of national power. To accomplish this, Steven Hardesty proposes ‘focusing on those elements—tenets, Mission Analysis, and Course of Action development—where revising is most urgently needed and will have the greatest effect on the entire planning process’.12 The deliberate planning process does not need new concepts; it just needs to be looked at in a new light.

Decision-Making - Adaption Cycle vs Boyd Cycle

Before entering an in-depth discussion of the Adaption Cycle and the Boyd cycle, more commonly referred to as the Observe, Orient, Decide and Act (OODA) loop, it is important to understand what they represent. The OODA loop has been described in military circles as a decision cycle and a command and control process. At their foundations, both cycles represent a method for interacting with the surrounding environment. The Adaption Cycle could be thought of as a variation of the OODA loop, but it possesses seemingly minor differences that actually represent drastic changes to decision-making fundamentals. The Adaption Cycle also carries a potentially dangerous undercurrent into the Joint Land Combat concept in that it cedes the initiative to an enemy that is always below the discrimination threshold.

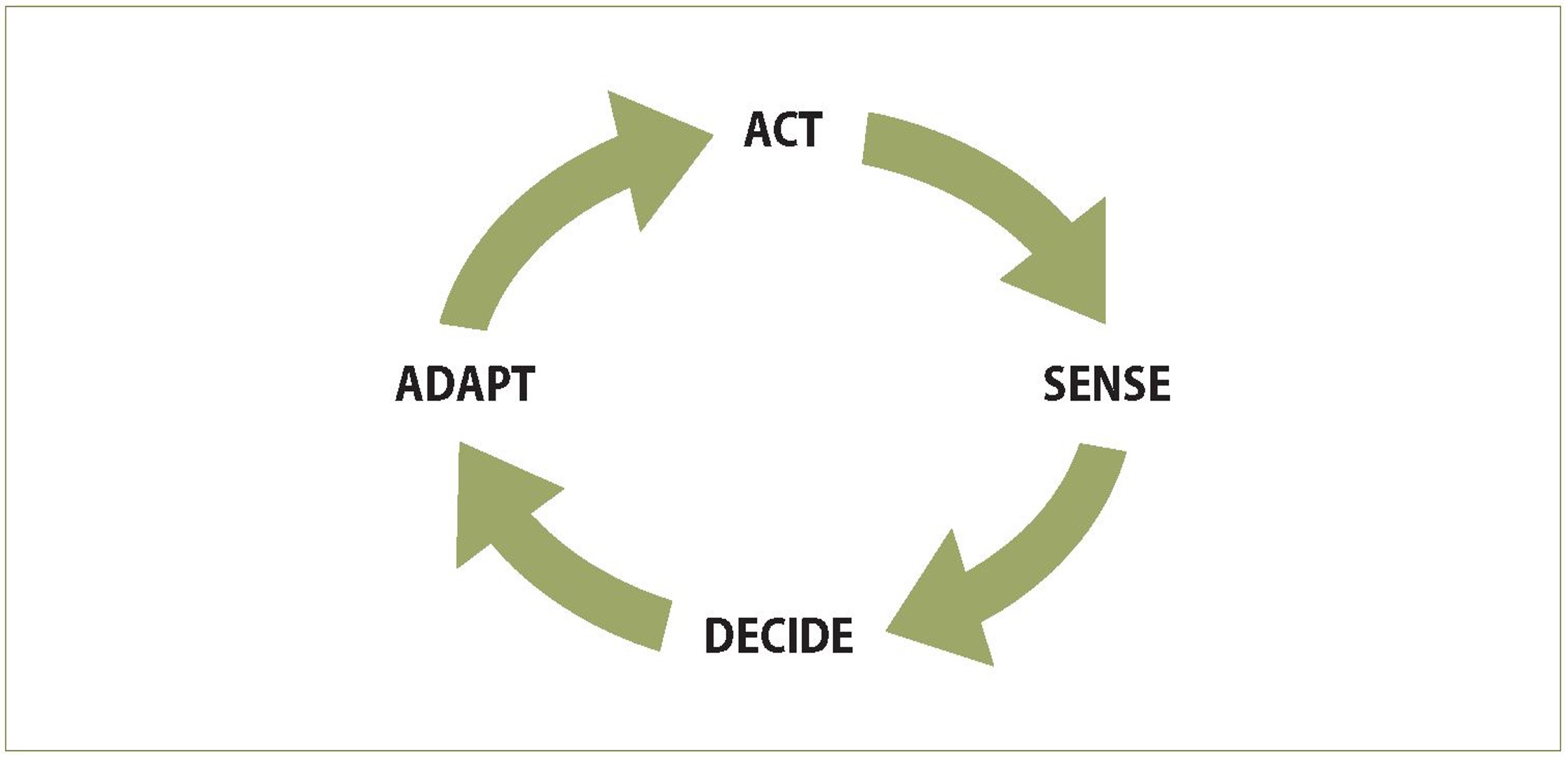

The Adaption Cycle (Figure 1) is presented in Adaptive Campaigning as a response to the ‘complex adaptive system’ that exists on the modern battlefield. It is a decision-making process that stems from the Adaptive Action planning process:

The complexities of this system are such that it cannot be understood by remote analysis alone; rather, detailed situational understanding will only flow from physical interaction with the problem and success will only be achieved by learning from this interaction.13

The assumption is that detailed situational understanding will only come after multiple iterations of the cycle where the Land Force continuously and rapidly adapts to a changing situation. Adaptive Campaigning thus characterises complex war as a ‘continuous meeting engagement’ in a competitive learning environment.

As shown in Figure 1, the Adaption Cycle is a four-step process of act-sense-decide-adapt. Adaptive Campaigning states that this is because ‘land forces will have to fight for and not necessarily with’ information.14 As a result, this hypothesis places act as the first step in the process. Action in the context of the Adaption Cycle is undertaken to stimulate a response and to test the Land Force understanding of the battlespace. The Land Force must then sense and interpret enemy reactions before it can decide when and how to adapt. This third step in the process, along with understanding what the response means and what should be done, appears to be the most critical as described in Adaptive Campaigning: ‘Once we have understood, we can decide what is happening and decide what should be done’.15 Finally, the Land Force will adapt. To do this, the Land Force must learn how to learn, know when to change, and challenge understanding and perceptions.

Figure 1. The Adaption Cycle

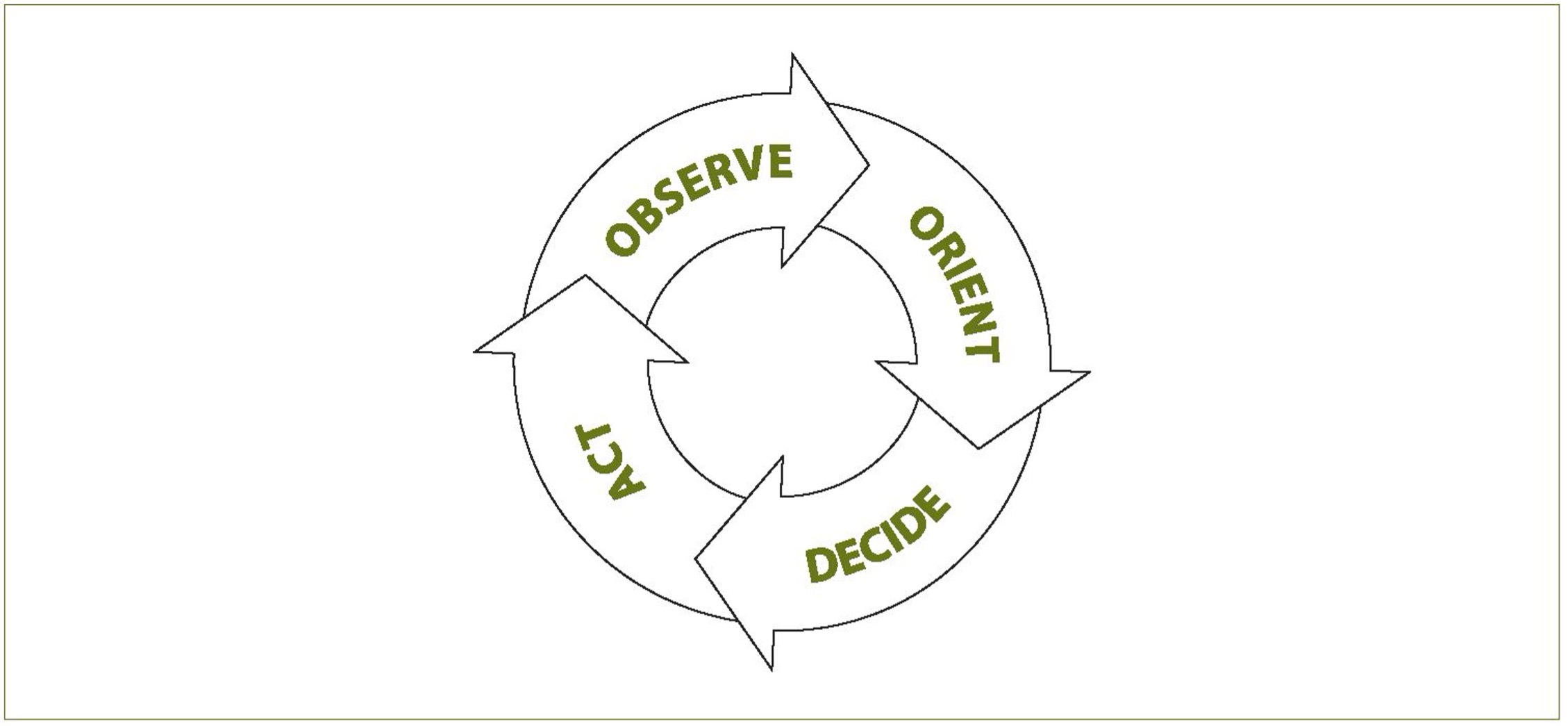

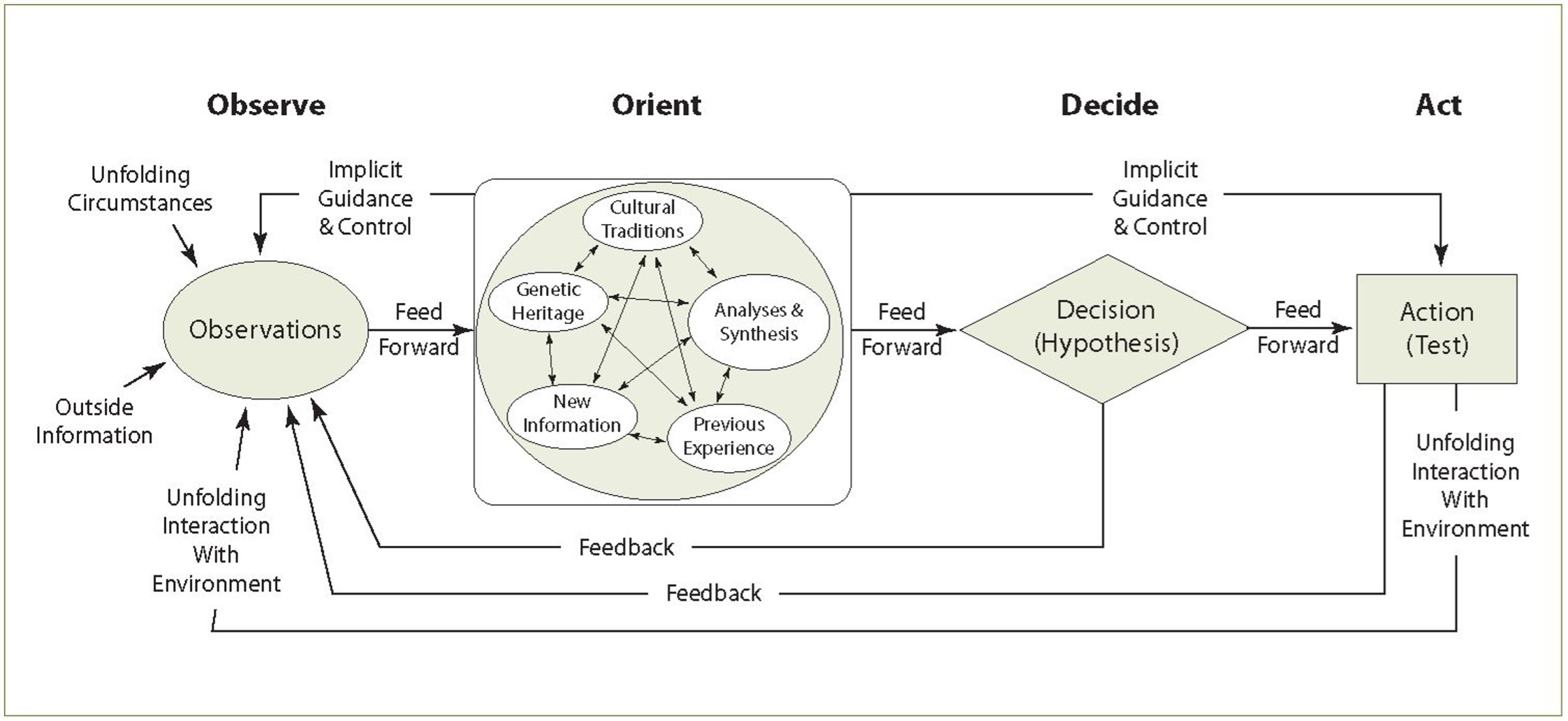

What about the OODA loop? It is a product of the late Colonel John Boyd, a US Air Force fighter pilot who made significant contributions to developing US Marine Corps manoeuvre warfare philosophy in the 1980s. He theorised that a participant in any conflict will engage in four activities: he must observe the environment, orient himself to what it means, reach a decision, and act on that decision.16 Marine Corps doctrine depicts the OODA loop as shown in Figure 2.17 Unfortunately, even this is not totally correct as, like the Adaption Cycle, it is oversimplified. Boyd’s final OODA loop is represented in Figure 3.

Why is the Boyd cycle better than the Adaption Cycle? First, a cursory glance at the depiction and the description of the Adaption Cycle shows act as the first step. As stated above, this is necessitated by the concept of fighting for, not with, information. The implication is that action will take place before sensing or even planning and represents a process that no military commander would undertake. Accepting that this may be a limitation of the conceptual explanation given in Adaptive Campaigning, is it not true that military commanders over the past two millennia have had to fight for information? This is not a new characteristic of the battlespace and certainly does not warrant the development of a new decisionmaking construct.

Figure 2. The OODA Loop as presented in MCDP 6.

Second, the Adaption Cycle provides no pathway to produce increased operational tempo via mission command. The OODA loop does. Adaptive Campaigning states that mission command ‘promotes a faster and more effective learning cycle and therefore lends itself to greater levels of adaptation’.18 This statement is incorrect as mission command has little or nothing to do with learning and everything to do with orientation and decision-making. Orientation allows for unpredictable events, which promotes a faster decision cycle through mission command. The inputs into orientation are varied: cultural and genetic heritage, previous experience and many others. It provides the filter through which we move directly from observe to act. In Figure 3 it is shown as ‘implicit guidance and control’. In military circles it is known as mission command. The Adaption Cycle does not include this mechanism.

So where does learning fit into the OODA loop? Learning is reorientation. Agility, defined as the ability to change one’s orientation rapidly in response to external influences, is the main output of Boyd’s theory of manoeuvre warfare. This is what will enable the Land Force to conduct operations at a higher tempo than the enemy. In the OODA loop, decisions are only necessary when action does not flow directly from observation via mission command. A decision therefore is a hypothesis and becomes part of the learning process. As a consequence, the necessity of having to make decisions slows down the process. It then becomes vital to feed the results of the decision back into orientation to re-enable implicit guidance, and control and further develop shared situational awareness. The organisation that can do this faster will hold a great advantage.

Figure 3. Boyd’s Final OODA Loop

The OODA loop is just as relevant on the complex battlefield as it was on the conventional battlefield. Orientation is the schwerpunkt, the most important step in the process. Boyd described orientation as a ‘many sided, implicit cross-referencing process’ that has its foundations in genetic heritage, surrounding culture and previous learning. This is where success in the complex battlespace will be achieved. Army values, previous experiences and outputs from the planning process such as shared situational awareness will combine to create mental models that every soldier will take to the fight. These mental models of the environment are necessary for the cross-referencing process to take place. In this process, the ‘observer’ is looking for mismatches between what was predicted and what is actually happening so that orientation can be changed and follow-on action can be derived. These mental models are one of the outputs of the deliberate planning process and are critical to generating operational tempo and enabling tactical execution and mission command. They will also play a critical role in execution and creating baselines, as explained in the next section.

In the end, the Adaption Cycle is unnecessary at best, misleading at worst. The development of this concept indicates that the OODA loop is inadequate in the complex environment. In fact, the premise can be supported that it is more relevant now than ever before as Western militaries push decision-making down to the lowest level. It is also important to note that multinational corporations such as Toyota have proven that the OODA loop is a credible tool in the business world, an environment that is arguably more complex and diverse than the modern battlefield. The Adaption Cycle should be removed from Adaptive Campaigning and should be replaced by a fresh look at existing methodologies, such as Boyd’s final OODA loop and its applicability in the complex environment.19

Execution - Joint Land Combat and the Combat Hunter

The final point of weakness in Adaptive Campaigning is in the approach to Joint Land Combat. This line of operation describes an inwardly focused process, driven by the concept of the Adaption Cycle. It is based on utilising the Adaption Cycle at the tactical level and is described as a ‘continuous meeting engagement’.

Therefore, manoeuvre elements must be prepared to cope with an enemy who will often fire the first shot. As a result the Land Force must be prepared to absorb that shot, survive, and then develop the battle in contact.20

These statements are factually correct and the theme of ‘surviving first contact’ has taken hold in Army development circles. It is hard to argue with any of the above rationale, especially in the context of an enemy that can lie below the discrimination threshold until he chooses to expose himself. The weakness of Adaptive Campaigning in this approach is a sin of omission rather than a sin of commission. There is no mention of how manoeuvre forces will lower the discrimination threshold, maintain the initiative and engage the enemy first. We are left with only the tactical Adaption Cycle where action is taken to stimulate the enemy (get him to fire the first shot and raise himself above the discrimination threshold), first contact is survived, and the battle is developed. Joint Land Combat seems to be describing a process to be executed rather than a problem to be entered. One can almost picture a young infantry platoon commander giving orders before a patrol: ‘Okay boys, we’re going to go out there and survive the first shots and then we’ll execute our game plan’. This is not a morale boosting concept for the young soldier on point. More importantly, the Army has ceded the initiative to the enemy before the first soldier has arrived in theatre by focusing inwardly on the effect on the Land Force of the enemy remaining below the detection threshold.

The Marine Corps is taking a different approach to this problem. Going back to first principles, MCDP 1 Warfighting states:

Orienting on the enemy is fundamental to maneuver warfare.... We should seek to identify and attack critical vulnerabilities and those centers of gravity without which the enemy cannot function effectively. This means focusing outward on the particular characteristics of the enemy rather than inward on the mechanical execution of predetermined procedures.21

The Marine Corps is looking at ways to maintain the initiative through an outward focus on the enemy and the ability to stay below the discrimination threshold. Rather than ceding this advantage as Adaptive Campaigning does, the Corps is striving to lower the threshold.

The Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory (MCWL) has recently concluded the Combat Hunter Project, a field user evaluation focused on enabling a Marine to gain and maintain enhanced situational awareness in order to develop an offensive ‘hunter’ mindset. The goal of Combat Hunter is to ‘improve combat efficiency while reducing combat casualties through the application of skills used by hunters as they pursue their quarry’.22 The project specifically seeks to enhance the Marine’s ability to observe, move and act. Of note, a specific goal for the individual Marine is to act always as the hunter and never in reaction to the enemy. Every Marine will be trained and equipped to confidently seek the enemy and will engage them before they are themself engaged.23

While the fine details of Combat Hunter are beyond the scope of this article, the concept of baselines is relevant to the discussion of mental models, shared situational awareness and lowering the discrimination threshold. Combat Hunter defines a baseline as a reference point or series of points against which a Marine can evaluate his surroundings.24 Quite simply, it is a mental model carried forward from the orientation process of the OODA loop. Any individual must first have an understanding of what is normal for the operational environment before a baseline can be established. Every culture, town, neighbourhood and street has a baseline. Here we see how planning and decision-making are inextricably linked to execution. A good planning process will facilitate the development of shared situational awareness and common baselines. An established baseline will clearly be injected into the orient box in Figure 3. From this point, the combat hunter looks for disturbances to the baseline, or things that ‘just don’t seem right’. Combat Hunter breaks these disturbances down into two categories: additions and subtractions to the baseline. An addition is something that is ‘there’ that should not be there. A subtraction is something that is not ‘there’ that should be. It is up to the individual Marine and their small unit leaders to determine whether the detected disturbances are indicative of a threat. Functionally, a Marine must be able to identify disturbances in the baseline, assess whether that disturbance constitutes a threat, communicate and move to negate the threat and act to eliminate it.25 Again, we find ourselves back with the Boyd Cycle.

It is this lack of even a mention of retaining the initiative that makes the current description of Joint Land Combat inadequate. By focusing inward instead of on the enemy, the Australian Army is at risk of taking a concept into doctrine, training and capability development that neglects the fundamental aspects of initiative and the hunter mindset, and will allow the enemy to make the first move every time. While it will always be necessary to survive the first contact, the preferred method should always be to seek the enemy and kill them first. The Army would be well served by closely examining the conduct and results of Combat Hunter for possible inclusion in future training and doctrine.

Conclusion

While Adaptive Campaigning lays out some good frameworks for joint and interagency operations in the current environment, the concepts of Adaptive Action and the Adaption Cycle should be removed from the document. Both concepts are unnecessary and flawed. Adaptive Action is based on misunderstandings of the purpose and outputs of the planning process. The Adaption Cycle is thought to be necessary because of an incomplete understanding of the OODA loop, a tried and proven concept that has been used, knowingly or unknowingly, for centuries. Both of these concepts have led the Army down a dangerous path in Joint Land Combat which has resulted in an inward focused, process driven warfighting construct that does not meet strategic end states. As written, Joint Land Combat removes the emphasis from attacking enemy critical capabilities at the operational level and channels efforts away from finding ways to maintain the initiative at the tactical level. It is not too late to change our current thinking on these subjects and make sure the most effective concepts are integrated into capability development, doctrine and training.

Disclaimer: This article contains the author’s views and is not representative of official views of the United States Marine Corps or the United States Department of Defense.

Endnotes

1 Max Boot, The Savage Wars of Peace, Basic Books, New York, 2002, p. 113.

2 Directorate of Future Land Warfare, Adaptive Campaigning, Department of Defence, Canberra, 2007, p. 13.

3 Ibid., p. 9.

4 Ibid., p. 8.

5 United States Marine Corps, MCDP 5 Planning, Department of the Navy, Washington DC, 1997, pp. 15–16.

6 Clarke R Lethin, ‘1st Marine Division and Operation Iraqi Freedom’ in Thoughts on the Operational Art, Marine Corps Combat Development Command, Quantico, 2006, p. 20.

7 Richard Maltz, ‘Shared Situational Understanding: A Summary of Fundamental Principles and Iconoclastic Observations’, 2 August 2007, <http://www.d-n-i.net/fcs/pdf/maltz_shared_understanding.pdf>

8 Sun Tzu, The Art of War, translated by Samuel B Griffith, Oxford University Press, London, 1963, p. 101.

9 Charles E White, The Enlightened Soldier: Scharnhorst and the Militärische Gesellschaft in Berlin, 1801–1805, Praeger Publishers, Westport, 1989, pp. 10, 95.

10 United States Marine Corps, MCDP 6 Command and Control, Department of the Navy, Washington DC, 1996, p. 44.

11 Directorate of Future Land Warfare, Adaptive Campaigning, p. 9.

12 Steven A Hardesty, ‘Rethinking the Marine Corps Planning Process: Campaign Design for the Long War’ in Thoughts on the Operational Art, Marine Corps Combat Development Command, Quantico, 2006, p. 57.

13 Directorate of Future Land Warfare, Adaptive Campaigning, p. 7.

14 Ibid., p. 31.

15 Ibid., p. 10.

16 Chet Richards, Certain to Win, Xlibris, United States, 2004, p. 62.

17 United States Marine Corps, MCDP 6 Command and Control, p. 64.

18 Directorate of Future Land Warfare, Adaptive Campaigning, p. 10.

19 See Chet Richards and Don Vandergriff, ‘Is Warfighting Enough’, Marine Corps Gazette, February 2008, p. 56.

20 Directorate of Future Land Warfare, Adaptive Campaigning, p. 13.

21 United States Marine Corps, MCDP 1 Warfighting, Department of the Navy, Washington DC, 1997, pp. 76–77.

22 United States Marine Corps, Combat Hunter: Observe, Move and Act Tactics, Techniques and Procedures, Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory, 2007, p. 1.

23 Ibid., p. 2.

24 Ibid., p. 10.

25 Ibid.