Abstract

This article explores the role that Army health capabilities could play in an Adaptive Campaigning operational framework. The authors argue that, as the Army begins to recognise the importance of health support to the population, Army health personnel must take on responsibilities additional to their normal combat health role. These include the temporary provision of obstetrics, paedeatrics and midwifery to the indigenous population, the adoption of more flexible health unit organisations, and the provision of medical training to the local populace. The authors argue that without additional resources, a broader skill-set, more agility and more flexibility, Army’s health forces will not be positioned to adequately support future operations.

‘Today’s armed conflicts are essentially wars on public health.’

- Dr R Russbach, former ICRC Chief Medical Officer1

Introduction

Adaptive Campaigning – The Land Force Response to Complex Warfighting provides a philosophical framework to meet the complexities and demands of current and future military operations.

The role of combat health support has traditionally been seen as the conservation of combat power. To meet the challenges of Adaptive Campaigning, operational health support must move beyond the traditional combat health support boundaries and revisit the unique challenges and opportunities that ‘health effects’ can bring to help achieve operational success. Under an Adaptive Campaigning framework, military health support assets must not only provide combat health support to deployed troops but be postured to respond to the needs of a wider dependency (including civilian populations) as a primary role. To meet these challenges, deployable health elements will need to fundamentally adapt their current organisation, equipment and training.

This article highlights the implications for operational health support inherent in Adaptive Campaigning and details doctrinal, organisational, philosophical and equipment challenges that will be required to meet operational health demands in complex operations. The article will cover:

a. A summary of the conceptual basis of Adaptive Campaigning

b. Suggested health effects across the five lines of operations

c. Considerations for defining and achieving strategic success

d. The effects of Adaptive Campaigning on operational Land health capabilities.

Adaptive Campaigning

Earlier tactical doctrines distinguishing between low, medium and high-intensity conflict have lost relevance; recent deployments have shown that forces simultaneously face a combination of tasks, such as counterinsurgency, stabilisation, peace support, conventional warfighting and humanitarian responsibilities. In 2006 the then Chief of Army Lieutenant General P Leahy identified that tactical elements require access to an appropriate array of lethal and non-lethal weapons; they need to be protected, equipped and structured to operate and survive in a potentially lethal environment; and they need to retain the ability to perform diverse concurrent humanitarian, counterinsurgency and peace support tasks.2 This requirement to adapt doctrine from solely warfighting to include reconstruction, counterinsurgency, security, peace support operations, civil-military cooperation and humanitarian support gave rise to the concept of Adaptive Campaigning.3

In its publication, Adaptive Campaigning – The Land Force Response to Complex Warfighting, the Future Land Warfare Branch identified that contemporary operations will involve multiple diverse actors competing for the allegiances and behaviours of targeted populations. Consequently, the outcome of future conflict will increasingly be decided in the minds of these populations rather than on the battlefield. As a result, a comprehensive approach to future Land Force operations is required, thus Adaptive Campaigning.

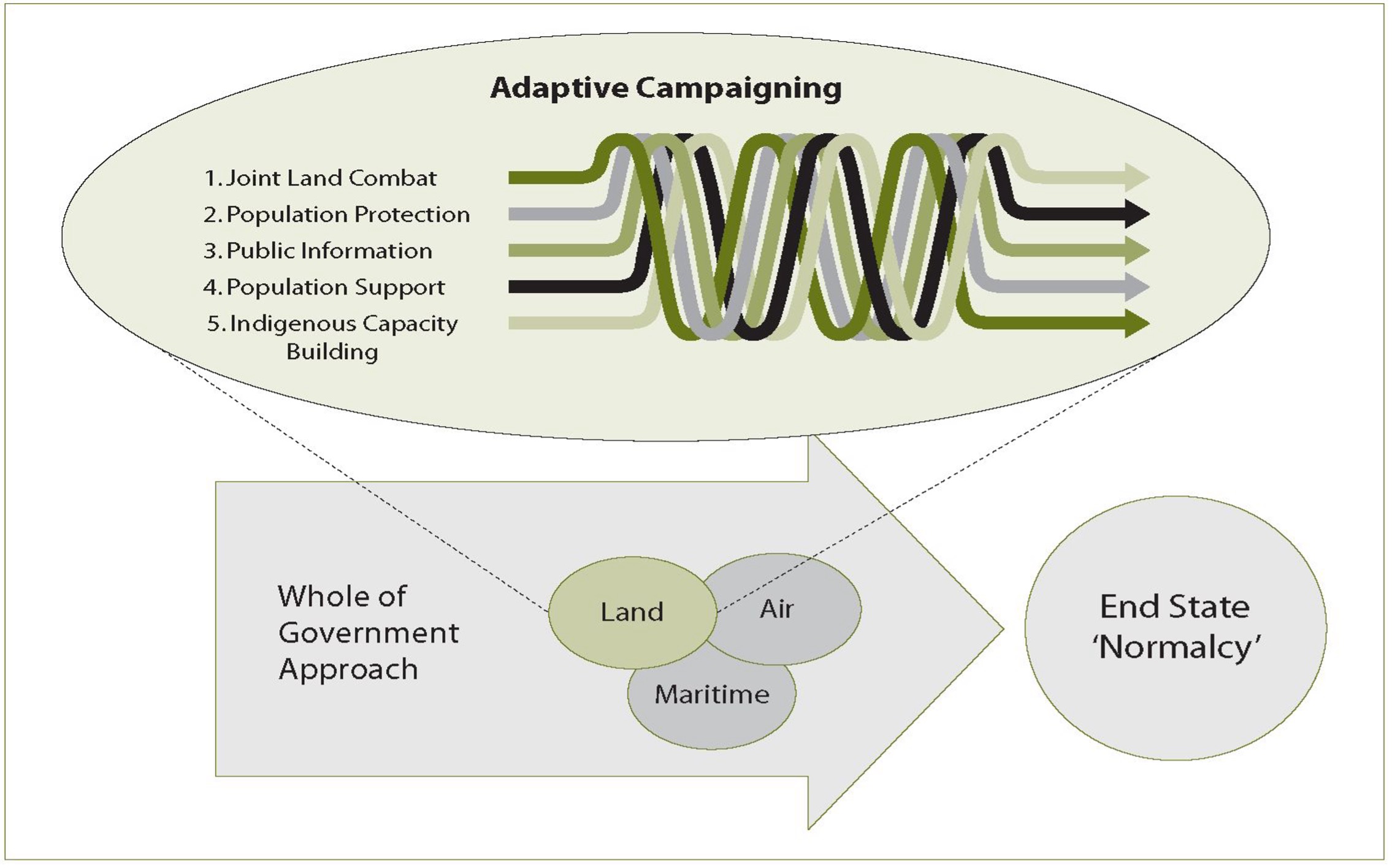

Adaptive Campaigning is defined as: ‘Actions taken by the Land Force as part of the military contribution to a Whole of Government approach to resolving conflicts’.4 Adaptive Campaigning comprises five interdependent and mutually reinforcing lines of operation, shown in Figure 1.5

- Joint Land Combat – actions to secure the environment, remove organised resistance and set conditions for the other lines of operation.

- Population Protection – actions to provide protection and security to threatened populations in order to set the conditions for the re-establishment of law and order.

- Public Information – actions that inform and shape the perceptions, attitudes, behaviour, and understanding of target population groups.

- Population Support – actions to establish/restore or temporarily replace the necessary essential services in effected communities.

- Indigenous Capacity Building – actions to nurture the establishment of civilian governance, which may include local and central government, security, police, legal, financial and administrative systems.6

Figure 1. The Adaptive Campaigning lines of operation

Health Effects Across the Five Lines of Operation

Fundamental to Adaptive Campaigning is the ability to influence populations and their perceptions, which is becoming the central and decisive activity of war.7 The provision of health services to indigenous populations offers a potent tool for shaping perceptions, and improving quality of life and personal safety. Enhancing the ability of the existing government to provide sustainable infrastructure and basic health care delivery systems builds trust and creates a tangible link between a central government and the people. Health care is a pillar of civil stability.

It is important to distinguish between humanitarian assistance and ‘medical engagement’ in an Adaptive Campaigning context. Humanitarian assistance provides limited service delivery assistance and meets a political purpose, but is not provided by the host nation and is therefore seen as external assistance. Medical engagement involves using health care to shape a particular health effect. This may be a short-term crisis intervention, a ‘hearts and minds’ campaign or a longer term focus on capacity building and reconstruction within the host nation. Health effects need to be viewed as an extension of ‘non-kinetic’ or ‘soft power’ in achieving whole-of-government objectives.

Adaptive Campaigning recognises that tactical actions taken along one line of operation will likely have an impact on one or more of the other lines of operation.8 Operational experience has shown that the ability to orchestrate effects across all five lines of operation is a key ingredient to generating success for the Land Force, and each of these lines of operation hold specific implications for health support.

Joint Land Combat

Joint Land Combat recognises that to achieve a persistent, pervasive and proportionate presence in urban terrain, it will be necessary to utilise relatively large numbers of small combined arms teams that have the capacity to ‘swarm’ in support of specific surge operations.9 In terms of health effects, the key factors that will predicate Land health success in Joint Land Combat operations are discussed below.

a. Protected health assets: Adaptive Campaigning will see large numbers of small combined teams (supported by joint assets) operating in complex terrain, resulting in increasing pressure on the Land health unit’s ability to effect casualty evacuation. Small numbers of casualties dispersed amongst complex terrain make protected surface evacuation assets essential. Further, operational experience in modern theatres has demonstrated that displaying the Red Cross symbol offers little protection against insurgent attack, and as such health capabilities—particularly those involved with casualty collection and transportation—require greater levels of protection than in previous conflicts.

b. Combat health: Combat health must be able to support many small teams, while retaining the ability to quickly surge in support of swarming operations. Air evacuation from the point of injury directly to Level 2+ facilities is now a routine process, implying that Level 1 and 2 health capabilities must be located closer to the point of injury to remain relevant, or risk being over flown.

c. Manning limitations: Increased lethality, improved communication capabilities and enhanced mobility of Australian Forces has resulted in reduced force densities in recent years. Health is not immune to manning restrictions and financial constraints, and each position deployed must be weighed up against a perceived loss of combat power or reduction in the total number of combat arms. ‘Our people are not just a fundamental input to capability—they are our capability.’10

d. Evolution of trauma care: The nature of casualties sustained during current expeditionary operations differs from previous campaigns. Although the casualty load is low by comparison with previous conflicts, the injuries are complex, society’s expectations of outcomes has changed, and injury management is vastly more resource intensive.11 The predominant injuries amongst coalition troops in Iraq are burns and blast effects related to improvised explosive devices.12

Trauma care has undergone a revolution in the last two decades and this is particularly evident on the battlefield. The move to ‘damage control’ philosophies, combined with better personnel protection such as enhanced combat body armour, has seen significant improvements in overall survival of often seriously injured casualties. Damage control, however, comes at a cost, including the ability to provide well trained ‘first responders’ armed with novel haemorrhage control measures (such as combat applied tourniquets and haemostatic agents), capable of instigating action not in the ‘golden hour’ but rather the ‘platinum ten minutes’ following initial trauma. Effective damage control is predicated on the provision of far-forward intensive care and resuscitation capabilities, proximate trauma surgery, and intensive care-level strategic evacuation to an appropriate facility, usually well outside of the theatre of operations.13 Definitive and highly sophisticated surgical intervention should be achieved within 48–72 hours of initial wounding. This is also reliant on the ability to source and provide often massive amounts of blood and blood products as a part of the resuscitation phase, which carries a significant logistical burden. Such highly sophisticated trauma facilities meet the needs of the coalition casualties but are rarely postured to deal with the vast civilian dependency.

Population Protection

Population protection operations require large-scale collective action. This line of operation will require a robust, sustainable and flexible Land health structure that facilitates, amongst other things, the following tasks:

a. Provision of combat health support.

b. Provision of primary health care to local law enforcement elements, security agencies, non-government organisations (NGOs), other government agencies (OGAs), host nation personnel and contractors. This dependant population can be considerable and is often underestimated during planning processes.

c. Within an Adaptive Campaigning construct, Army retains its moral and ethical obligation to provide health support to sick and injured civilians who access military treatment facilities, regardless of their combatant status and is still governed by International Humanitarian Law and the provisions of the Geneva Conventions.14 This includes responsibility for civilian casualties resulting from Australian/coalition kinetic actions.

d. While providing security to civilian health assets is not the responsibility of military forces, the freedom of movement (or otherwise) afforded to civilian health organisations will considerably influence the level of support required by Land health units. Land health units can enhance the capacity of indigenous health assets through the provision of equipment, training, administration, logistics, supervision, and the coordination of task management and personnel.

e. Protection of health personnel poses challenges in interacting with local communities. One of the keys to effective counterinsurgency operations is presence. Moving freely amongst a community to achieve presence requires careful consideration of the security implications for health care providers. Cultural expectations can have an impact on health care delivery and may require variance from traditional gender roles or an increased participation of the female health workforce in order to gain access to and influence certain sectors of the community (women and children).

f. During population protection operations Land health elements will be required to provide medical treatment for prisoners of war, a function that is covered within existing doctrine. However, medical care is also likely to be required for civilian prisoners, political prisoners, issue-motivated groups, insurgents, indigenous VIPs, contractors and nationals. The Australian Defence Force’s (ADF) current doctrine and training models do not well support these tasks.

Public Information

Personal contact and proximity are fundamental components of human interaction, and while technology offers mechanisms for influencing public perception through the distribution of mass information, the subtleties that exist in intimate association with others often proves the most effective tool in a public perception campaign. People are influenced by people. Health elements have a unique opportunity to demonstrate the humanitarian aspect of a deployment and individual acts of health support can positively influence the attitudes of a population. There is a ‘need for our deployed Land Forces to work among the people, and to establish a broad relationship with the supported population’.15

Health service personnel interact with indigenous populations in intimate forums, offering strong opportunities to influence and support perceptions of success across all lines of operations. Health planners should remain cognisant of the ability for tailored health effects to influence the information battle positively, as perception management is an important pillar of Adaptive Campaigning.

The credibility and legitimacy of the security forces, as viewed by the indigenous populations, will be greatly enhanced if appropriate health effects are employed to shape perceptions, attitudes and understanding of the targeted groups. While the use of health capabilities as part of an integrated public information campaign might raise ethical and legal questions in terms of the Geneva Conventions and the International Committee of the Red Cross, the ability for the health services to support the public information campaign is certainly significant. For example, the deployment of relatively inexpensive primary health care capabilities (including dental) can generate significant public support, while maintaining a light operational footprint.

While health care can meet strategic military objectives in a subtle manner, the effect of overt campaigns may have unforeseen consequences. Suggestions that medical assets are being used to support factional allegiances or as sources of intelligence can gravely undermine the validity and neutrality of both medical personnel and the overall force.16 This is well demonstrated by the Yugoslav Government’s allegations of spying against a CARE Australia worker in Kosovo having a detrimental effect not only on CARE but on all NGOs in the region. Although General Sir Michael Rose has stated that ‘there is no such thing as impartial humanitarian assistance’17 this is in conflict with the ethical requirement to provide health care based solely on medical need regardless of political, military, cultural or other biases.

One of the key elements to avoid allegations of bias is consistent provision of health standards, which demonstrates that Land health components will not provide one level of care to one element of the community, while treating other groups with less vigour. Accepting responsibility for even a relatively small element of an indigenous population’s health requirements necessitates careful planning, reinforcing the need for strategic health outcomes to be integrated with the strategic goals across all five lines of operation.

Population Support

Population support includes actions to provide essential services to affected communities to relieve immediate suffering and positively influence the population and their perceptions. By necessity, actions taken along this line of operation are closely aligned to public information. The aim of population support is to conduct integrated civil operations that:

a. Reduce the likelihood of humanitarian crises

b. Mitigate the effects of the damage to key infrastructure as a result of combat

c. Reduce the internal displacement of populations

d. Encourage a return to normalcy within communities, and

e. Build confidence in the viability and effectiveness of the governance arrangements that are in place.

In complex operations, health facilities are often the first to be destroyed and the last to be rebuilt.18 Local health care providers may still be operating in some areas but their services may be inadequate due to lack of personnel, facilities or resources.19 Insurgent action may target health providers, relief convoys and health facilities in an attempt to undermine confidence in the intervention force and create fear and uncertainty.

Civilian populations also have significant underlying dependencies with health issues which are non-conflict related, reflecting the consequences of a breakdown in the standards of living and chronically inadequate health care systems.20 Layered into this are the realities of human rights violations, competition for limited health assets, the rise in malnutrition and infectious disease, and an increase in infant and maternal mortality rates that are associated with refugees or internally displaced populations.21 Military forces have historically taken on roles in providing commitment to public health interventions such as engineering support, provision of clean water, and road repairs to allow access to rural areas, but are rarely configured to meet the complex need of a civilian population dominated by the elderly, women and children.

Within an Adaptive Campaigning construct, Army retains its moral and ethical obligation to provide health support to sick and injured civilians who access military treatment facilities, regardless of their combatant status as governed by International Humanitarian Law and the provisions of the Geneva Conventions.22 This includes responsibility for civilian casualties resulting from Australian/ coalition actions.

Army’s operational health units, however, have no obligation to provide health care to civilians presenting with chronic or non-acute conditions, or to provide care when satisfactory host nation or NGO health capabilities are available. This requires a stringent casualty regulation system, clear agreement and task allocations between different health care providers and strict adherence to medical rules of engagement (ROE). Tensions often exist and philosophical differences regarding the use of military health care as a tool of government must be acknowledged.

Population support operations require integrated action across military forces, NGOs and OGAs. In the early phases of an operation it is likely that the Land Force will be the lead agency in health care provision, simply because the combat resilience of this component makes it better suited to the rigours of an operational setting, compared to NGOs and OGAs.23 A disciplined, military response during the initial period can do much to set the preconditions for success for subsequent NGO/ OGA providers. Understandably, integration between Land Forces and NGOs and OGAs (along with restoration of host nation facilities) is a key factor for longer term solutions and disengagement.24 The importance of effective interoperability between Land health components and relevant NGOs and OGAs cannot be understated.

Military health involvement in population support operations requires careful planning. The level of care provided should be affordable, achievable and sustainable, and must not interfere with the provision of health care to the military force. Access, egress and resource usage by civilians entering military medical chains must be controlled to prevent the system becoming rapidly overloaded. This can only occur in the setting of mutual assistance between humanitarian, host nation and military medical staff.25

Strict adherence to accepted local and NGO treatment protocols when treating civilian patients facilitates standardisation of treatment, minimises perceptions of differential standards of care, and facilitates transfer of patients from military to civilian health facilities. Military casualties will generally be rapidly evacuated beyond the immediate operational area to sophisticated ‘home nation’ medical facilities; however, this option is not available for ‘non-designated’ civilian personnel. A robust civilian evacuation chain is essential, as this will help to prevent Land health assets from becoming committed to managing longer-term civilian patients.

Treatment eligibility matrixes and medical ROE need to be carefully articulated to avoid perceptions of bias. In providing health care to civilians, which extends beyond our international obligation, ethical conflicts may exist if restrictions are applied to determine who may or may not access the full capabilities offered by Land health facilities. Discriminators are likely to include national origin, VIP status (i.e. local leaders and politicians) and Security Sector Reform status.

Provision of military health services must be balanced against the need to minimise the operational health footprint. This is best achieved by utilising low footprint interventions whenever possible. In long-term engagements within a fragile security situation it may be necessary for the defence force to contribute to rebuilding civilian health infrastructure to facilitate Land health disengagement. An example of a much underutilised capability is dental, which is attractive in terms of its ability to define and limit tasks, it offers minimal ethical dilemmas, and it is characteristically easy to define in terms of treatment matrices and exit strategies.

Indigenous Capacity Building

Indigenous capacity building from a health effects viewpoint includes provision of transferable skills, restoration of confidence in local health providers, equipment repair and maintenance, facility management and strategic health planning.26 Indigenous capacity building is relatively low cost and high benefit compared to ongoing ‘service provision’; it offers a greater long-term benefit and facilitates military disengagement.

While it is usually preferable for civilian or national government agencies to lead and for the army to assume a role in facilitation, health reporting and administrative support in the early phase of a mission, there may be a vacuum of resolve in which the army must assume primacy. Strategic health planning and health administration is an under-recognised role in reconstructing fractured health capability. Army’s health planning ability could be utilised in multi-agency planning to enable the host nation to enact and govern a developing and integrated health structure. This avoids inherent inefficiencies and duplication of effort, and enables mutually agreed plans and solutions that work in a specific cultural context to be implemented.27 It is crucial that the sustainability and appropriateness of health standards within that population are recognised, respected and used as the basis of planning.

Transferable medical skills can be provided at all levels of the health continuum, from basic community first aid and education campaigns, nurses aide training, re-skilling or credentialing of specialist health officers and strategic health planning and administration. Health education and training provides good value for money and represents an ongoing future investment.

In a community model, obstetric support and midwifery, paediatrics and care of the aged are more important than a traditional military combat health support trauma model. Generally the best effects can be achieved if curative care receives the lowest emphasis, with effort instead placed on supporting and enabling existing health capability rather than replacing it with a military (or NGO) model. Provision of sophisticated and unsustainable military health assets risks undermining confidence in the local health providers and does not support an emergent government’s role in service provision.

The ADF is well positioned to engage in transferable health skills, having a robust training structure with experience in internationally recognised and credentialed health programs. Courses that move from individual training to ‘train the trainer’ should be embraced. Health courses that exceed one month in duration may prove impractical (due to indigenous attendance and the normal deployment rotation of ADF forces); however, shorter courses should prove manageable. While the UK’s Battlefield Advanced Trauma Life Support, Battlefield Advanced Resuscitation Techniques and Skills, and Advanced Trauma Life Support courses offer good models, these may not be appropriate for the environment. A good model for this type of approach is the ADF obstetric course. During times of conflict, health practitioners have often suffered skill degradation, and the confidence gained by attending such skills courses combined with the opportunities to mentor and influence should not be underestimated—joint professionalism and expertise in delivering health care has the ability to override ideological differences and support joint reconstruction objectives. However, any teaching roles must be undertaken with a clear understanding of what level of care is sustainable and appropriate within the local community. Additionally, ongoing support in the form of access to journals or mentoring programs (such as those provided by the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons’ Interplast program) concentrate on both transferring experience and individual mentoring, and should form part of any capacity building initiatives.

Transferring skills that enable indigenous populations to repair principal medical items, such as an anaesthetic machine, ventilator or key laboratory analyser, is preferable to donations of equipment that are unsustainable; however, equipment repair and maintenance is generally poorly resourced across Army’s Land health units. Medical equipment is particularly expensive and carries a significant maintenance liability requiring specialist technical inspections, tooling and repair. As Land health has increasingly moved to contracted solutions for medical equipment maintenance, this skill set has degraded, particularly in combat health support settings. Indigenous capacity building initiatives should remain cognisant of Army’s limited ability to support medical and dental equipment, and appropriate measures should be taken to facilitate this service. In addition this needs to be linked with other equipment aid programs such as Department for International Development and AusAID.

Indigenous capacity building sets the conditions for transition to indigenous health frameworks, and as such is fundamental to shaping the Land Force’s exit strategy.

Defining and Achieving Strategic Success

The success or otherwise of a force in combat has traditionally been the benchmark against which success is defined. Recent operational experience, however, suggests that how the fight is fought is as important, if not more so, than the numbers of enemy units destroyed. While gains can be made from short-term tactical victories, strategic implications can be catastrophically affected as a consequence of quite isolated incidents, particularly in terms of how the Land Force’s actions are perceived by the local population. Success is therefore not simply a measure of tactical advantage, but instead requires consideration across all five lines of operation.

Understanding how indigenous populations assess success in terms of health effects is an important pillar for Adaptive Campaigning. The ability to adapt to a changing environment requires robust measures of effectiveness. Defined measures of health effectiveness facilitate the political dimension both at home and abroad and provide transparency. Traditionally health reporting and analysis is often limited and military health projects are poorly linked with other projects.28

Perceptions of improvements in health care need to be interpreted within the cultural framework of the society under review, and expectations must be shaped against realistic and sustainable benchmarks. For example, improvements in basic infection rates are more relevant performance metrics than cancer treatment or trauma outcomes.

From a Land health perspective, success needs to be measured across all five lines of operations, as the international community rightly has significant expectations of our health capability. While this paper does not seek to develop formal key performance measures for measuring how successfully health effects have been applied within an Adaptive Campaigning environment, indicative factors for each line of operation are offered as follows:

a. Joint Combat Operations. A range of data is available to determine the success of the combat health support in supporting joint combat operations, particularly in terms of casualty evacuations achieved within 30 minutes, wound surgery conducted with 60 minutes (from the time of injury), survival rates of combat casualties, and post-surgical infection rates.

b. Population Protection. The health support requirements for the Land Forces do not differ significantly between joint combat operations and population protection operations, accepting that casualty rates will probably differ. However, implicit in population support operations is the need to meet lower-order needs, suggesting that provision of basic health services is an important factor in influencing the indigenous population’s perceived levels of safety.

c. Public Information. This means that all health service personnel within the area of operations must be trained in basic cultural, linguistic and media skills, and must have a reasonable understanding of local issues as they apply to implementing ADF health effects. Health commanders must foster a regular and open flow of information, and all staff must be aware of how their actions in dealing with indigenous populations, NGOs, OGAs and contractors can directly affect the perceptions of success. The many fleeting chances afforded to health staff where they can advance informational objectives should not be discredited. Human Intelligence staff have a variety of methods available for assessing the effectiveness of the public information campaign—such as questionnaires, discussions and feedback tools—and the success of the health effects components can equally be assessed via these methods.

d. Population Support. Disease epidemics, infectious diseases, dysentery and malnutrition are predominant in refugee and internally displaced personnel (IDP) camps and require commitment of environmental health assets such as vector control, childhood immunisation and engineering assets (e.g. clean water and sewerage) to minimise the increased risks of transmissible disease. Standardised reporting and outcomes measures exist and should be utilised.29

e. Indigenous Capacity Building. Understanding the health needs of the indigenous community is essential. Appreciating what is an ‘acceptable’ level of health support is a key factor in determining what indigenous capacities are required and Land health units need to accept that their goal is not necessarily a mirror image of Australia’s civilian health capabilities. It is also necessary to critically appraise the value of medical assistance given and to disseminate this information and ‘lessons learned’ into the international humanitarian community. Measures of health effectiveness should consider the relevance and effects of any health interventions. Post-deployment reports tend to focus on the number of patients treated in a facility, but this is inadequate without measures of how the intervention changed the health status of the patients or populations.30 For example, if equipment donations were made, relevant effectiveness indicators include whether the equipment was needed, used, and if problems were experienced with maintenance and education. Surrogate markers of effectiveness, such as peri-natal mortality and adverse outcomes, can also be useful indicators of effectiveness.31 Regardless of the indicators used, ultimately the desired health effects must have relevant measures of success to ensure that false dependencies, hollow successes and/or unrealistic expectations are not created.

Adaptive Campaigning - Effects on Land Health Capabiltiies

Health Planning

To deliver on the challenges of adaptive campaigning, Land health must demonstrate an increased focus on health needs assessment, health intelligence and inclusion of health planners at strategic levels to foster increased cooperation with NGO, OGA and civilian agencies. Operational health capability as a shaping effect also requires an increased focus on preventive medicine, vaccination programs, specialist capabilities that target civilian health-need groups (such as paediatrics and midwifery), and a robust ethical debate on treatment eligibility matrixes.

Health planning for a complex operation should include relevant government and humanitarian agencies prior to any deployment, which ideally would form part of an integrated training regime within Australia. Integrated health planning and training offers the opportunity to foster trust and interoperability between ADF capabilities, NGOs and OGAs, improving understanding of mandates, increasing the flow of health intelligence, and jointly contributing structures and health assets to a meet a common vision. This level of coordination requires a functioning medical coordination cell to act as the executing body for health support for all Australian Joint operations. A single medical planner embedded into the Joint Task Force Headquarters is unable to meet the breadth of coordination responsibilities or to identify and exploit health opportunities. The existing NATO model of Med Ops/ Plans and Patient Evacuation Coordination Cell provides a workable solution as a modular structure to be employed within an Australian CJTF.32

Health Intelligence

One of the tenets of Adaptive Campaigning is the ability to detect and respond to changes in the environment and use them to best advantage. In a health setting this requires effective health intelligence gathering and the ability to rapidly redirect health assets.

The ability to demonstrate incremental improvements in the standard of health care delivered by indigenous health facilities supports and validates the government and builds confidence in the community. This requires significant health intelligence pre-intervention and an acceptance that benchmarks may not be available, or may be subject to cultural variations. Agreement on uniform, achievable standards of care and performance metrics needs to involve all providers in the health care ‘space’. For longer duration interventions activity and intelligence data gathered during the operation becomes critical to demonstrating the effectiveness (or otherwise) of the mission.

Medical staff are, by virtue of their unique role under the Geneva Conventions, precluded from engaging in any information gathering activity. However, information can be gained from health capabilities regarding wounding patterns. For example, analysis of data obtained from the Joint Theatre Trauma Registry, combined with the observation that in 2005 in Iraq there was a dramatic increase in burns-related mortality, led to additional protection (Nomex) for deployed troops. Similarly, observation that insurgent snipers were targeting unprotected body areas led to enhancements (collars, side and groin protection) to combat body armour.33

Force Structure, Survivability and Agility

Rationalisation of operational health assets has occurred during extended periods of peace and recent low-level operations, and now threatens the ADF’s ability to meet the agility required by Adaptive Campaigning. Reliance on reservists to provide key health personnel for the ADF while providing a capability that cannot be generated within the permanent force also offers its greatest vulnerability.34 A further consideration is the effect of sub-specialisation in medicine which has resulted in an increased age and limited skill sets amongst key specialist personnel. Military planners must decide if the capability gap that now exists is to be met by recruitment or training of military personnel or contracted civilian professionals.

Current operations have seen an emergent focus on employing smaller operational teams to achieve particular effects within the battlespace.35 To meet the demands and agility required by Adaptive Campaigning, health should also move toward a task organised structure with the flexibility to provide combat support and non-combat health support modules and the ability to switch effort between capabilities. This requires a broadening from a traditional trauma model to include obstetrics, paediatrics, physicians and care of the elderly as core elements of operational health support. Provision of combat health care and trauma capabilities will retain primacy for ‘own forces’, but other aspects of health care need to be integrated into whole-of-government effects.

One of the key enablers to effective Land health operations is survivability. Current operations demonstrate the need to push resuscitation elements forward as far as possible (for example the medical early response teams utilised by the British in the Middle East Area of Operations (MEAO)). While this practice has no doubt saved lives and resulted in increased number of ‘not expected survivors’ it is a strategy that inherently increases the risk to health staff and carries a significant liability in terms of self protection training, improvised explosive device and counter ambush drills, increased weapon confidence, and the acceptance of health casualties.

Traditionally, the Land health capacity has been designed to sustain the force and assigned elements. This capacity, although it can be stretched to meet surge requirements, needs to be enhanced to adequately cope with the additional demands of population support operations. To meet these demands, Army’s operational health capability must undergo a subtle structural and philosophical change. Combat health support elements need to readjust to provide a damage control based capability. Current operations have demonstrated the need for this capability to be agile, well protected and well supported by strategic intensive care level aero medical evacuation.

To address population support and public information operations, health structures should include capability bricks for medical functions that have not historically been catered for in our planning. Capacity should be grown in areas such as paediatrics, public health obstetrics and gynaecology. While some of these skills exist within our Reserve specialist body, the ADF does not actively foster these capabilities as part of the force structure.

In supporting indigenous capacity building, an increased focus on health effects that support health reconstruction carries implications for equipment and training, which need to reflect a focus on delivery of transferable health skills, health education, equipment maintenance and repair, and mentoring local health providers in host nation facilities.

A consideration for operational planners is that while the health services look to generate capabilities that can better support all five lines of operation, these capabilities will create their own range of challenges in terms of recruiting, training and gender balance. Once deployed, health effects in support of population support operations will be limited if health assets cannot securely move around the area of operations to the various indigenous communities. In particular it must be appreciated that combat health capability and population support require specific and distinct capabilities and individual skill sets, and it is not possible to simply shift effort between the two.

The key to the Land health force’s success will be its ability to orchestrate effectively health effects across the five lines of operation within the battlespace. As a result, the Land health component must develop and maintain an inherent ability to shift its main effort rapidly within or across a line of operation, often responding in an environment of uncertainty where little information is available to the operational health planners. This ability to adapt is predicated on an agile force structure that generates flexibility across all five lines of operations, as well as the ability to sense and adapt the Land health’s responses to ensure that the right services are being provided, at the right place, at the right time. The ability to focus appropriate effort is founded on the following key capabilities:

a. Operational flexibility is the ability to maintain effectiveness across a range of tasks, situations and conditions. For example, the structure and capability of the health component can be reconfigured in different ways to do different tasks, under different sets of conditions. This implies a broader range of skill sets than currently exists at the combat health support level. Despite deploying a balanced operational health capability, it is reasonable to anticipate that the adaptive environment will require significant flexibility from a force structure perspective. This necessitates the ability to recognise that if the appreciation was wrong, more health assets may need to be completed to ensure that both combat health support and population support tasks are catered for. This may require involvement of contractors in base support tasks enabling uniformed health providers to move forward.

b. Operational agility is the ability to manage the balance and weight of effort dynamically across all lines of operation in space and time. This relies heavily on an effective (and ongoing) health intelligence campaign, on flexible force structures and on integrated health planning functions. Operational agility will also be enhanced by fostering the continued development of coordination mechanisms between the Land Force, indigenous groups, NGOs and OGAs.

c. Operational resilience is the capacity to sustain loss, damage and setbacks and still maintain essential levels of capability across core functions. This implies a depth of skills that does not presently exist in all areas of operational health, suggesting that specialised health bricks (such as obstetrics, paediatrics or midwifery) should be replicated across selected combat health support units, most suitably in the Health Service Battalions.

d. Operational responsiveness is the ability to rapidly identify then appropriately respond to new threats and opportunities within a line of operation. Like operational agility, this capability is largely predicated upon comprehensive health intelligence, coupled with integrated and robust health planning methodologies.

Recommendations

- Rationalise Australian combat health capability to ceiling of Role 2 enhanced (requires acceptance that individual sub-specialist capability is available to be integrated into coalition operations rather than inherent in Australian capability).

- Designate specific assets for mission tasking (in targeted humanitarian assistance, shaping effects) separate from those employed for force preservation.

- Develop capability bricks that specifically address the range of tasks required across the five lines of operations. Likely bricks include:

- Humanitarian assistance

- Obstetrics

- Paediatrics

- Public health

- Indigenous capacity building (i.e. health contract managers, health logistics, health administration and health planners).

- In developing health capability bricks that address likely tasks within Adaptive Campaigning operations, consideration also needs to be given to enabling NGOs and OGAs to fill specialised roles and functions within capabilities.

- Closer coordination, consultation and support between commanders, operations staff and medical planners.

- Integrate humanitarian assistance within formation operations, perception management and psychological operations plans.

- Focus health support on prevention and education, integrated with local health infrastructure.

- Land health personnel should receive formal training in NGO and OGA liaison.

- Indigenous capacity building requires health specialists (including Royal Australian Army Medical Corps General Service Officers) with contract management experience. The Reserve force offers an excellent opportunity for this role.

- Protection of health capability needs to be addressed.

- The impact of strategic aero medical evacuation across all lines of operation requires further consideration.

- Contractors have an evolving role in the provision of health support, and the implications of employing contractors within an area of operations requires careful consideration.

Conclusion

As the vast majority of conflicts around the world are unconventional it is important to recognise and adjust the strategies required. Delivery of medical capacity is an important adjunct to achieving whole-of-government outcomes in Adaptive Campaigning operations. Effective use of health assets as a form of ‘soft power’ may allow the operational commander to build confidence and trust within local communities and assist in achieving strategic and operational objectives.

Currently, Army’s combat health support does not have a doctrinal framework to support Adaptive Campaigning. Conventional combat health support may meet the needs of the military force but does not have the depth, agility or capability required to maximise health effects within an Adaptive campaign. New doctrine must be developed to describe how Land health components can be employed within an Adaptive Campaigning framework, with particular regard to the complexities surrounding treatment of civilian populations and to providing flexible and focused solutions to effects-based operations.

The primary role of Army’s combat health support elements remains the provision of health support to our own forces. Health effects, humanitarian assistance and other-than-direct combat health support can very quickly overwhelm military capacity. Medical planners have a responsibility to ensure that assets are not overextended or compromised, and that the treatment and legitimacy of military personnel is not jeopardised. At the same time, flexibility must exist to allow Land health elements to adapt as the ground situation changes. Executing health effects across all five lines of operations requires unconventional solutions not reflected in our current ‘conventional’ force structure.

To effectively utilise health assets in support of Adaptive Campaigning, the implications for doctrine, training, materiel, personnel, organisation and systems need to be assessed. This paper recommends that Army adopts a task organised and health effects based structure which will provide it with the flexibility and agility required to meet the operational health demands of the twenty-first century.

Endnotes

1 Future Land Operational Concept, Complex Warfighting, Department of Defence, Canberra, 2006.

2 P Leahy, ‘Hardening and Networking the Army – Towards the Hardened and Networked Army, Australian Defence Force Journal, Vol. II, No. 1, Winter 2004, pp. 27–36.

3 Department of Defence, Future Land Operational Concept, Complex Warfighting, p. 2.

4 Future Land Warfare Branch, Adaptive Campaigning – The Land Force Response to Complex Warfighting, Department of Defence, Canberra, 2006, p. 3.

5 Ibid., p. 4.

6 Ibid., p. 3.

7 Ibid., p. 3.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid., p. 14.

10 K Gillespie, Chief of Army Speech to the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 27 August 2008, <http://www.defence.gov.au/army/AdaptiveArmy/docs/Chief%20Of%20Army%20Sp…;.

11 S J Neuhaus, ‘Post Vietnam – Three Decades of Australian Military Surgery’, ADF Health Journal, Vol. 5, 2004, pp. 16–21.

12 Personal correspondence, Lieutenant Colonel S J Neuhaus, Colonel D Jenkins, USAF, Director, Joint Theatre Trauma Registry Systems Program, May 2008.

13 S J Neuhaus and J R Bessell, ‘Damage Control Laparotomy in the Australian Military’, ANZ J Surg., Vol. 74, January–February 2004, pp. 18–22.

14 S J Neuhaus and F Bridgewater, ‘Medical Aspects of Complex Emergencies: The Challenges of Military Health Support to Civilian Populations’, Australian Defence Force Journal, Issue 172, 2001, pp. 56–72.

15 Gillespie, Chief of Army Speech to the Australian Strategic Policy Institute.

16 Neuhaus and Bridgewater, ‘Medical Aspects of Complex Emergencies’, pp. 56–72.

17 S J Neuhaus, ‘Medical aspects of civil-military operations’ in Christopher Ankersen (ed), Civil-Military Cooperation in Post-Conflict Operations, Taylor & Francis Ltd, London, p. 207.

18 F Burkle, ‘Lessons learnt and future expectations of complex emergencies’, British Medical Journal, No. 319, 1999, pp. 422–26; R M Coupland, ‘Epidemiological approach to surgical management of the casualties of war’, British Medical Journal, No. 308, 1994, pp. 1693–97.

19 R Rushbach, ‘The International Committee of the Red Cross and Health’, International Review of the Red Cross, No. 260, 1987, pp. 513–22.

20 A K Lepaniemi, ‘Medical Challenges of Internal Conflicts’, World Journal of Surgery, No. 22, 1998, pp. 1197–201.

21 Division of Emergency and Humanitarian Action, World Health Organisation, Applied Health Research in Emergency Settings, Macfarlane Burnet Centre for Medical Research, Melbourne, 1999.

22 Geneva Conventions 1949, and two Additional Protocols 1977.

23 Future Land Warfare Branch, Adaptive Campaigning – The Land Force response to Complex Warfighting, p. 6.

24 Ibid.

25 G Kenward, T N Jain and K Nicholson, ‘Mission creep: an analysis of accident and emergency room activity in a military facility in Bosnia-Herzegovina’, Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps, Vol. 150, No. 1, 2004, pp. 20–23.

26 R Gilbert, USMC, ‘The Role of Medicine in Counterinsurgency’, delivered at the Asia Pacific Military Medical Conference XVII, Manila, Philippines, 15–20 April 2007.

27 P Abigail, et al, ‘Engaging our Neighbours: Toward a new relationship between Australia and the Pacific Islands’, Australian Strategic Policy Institute Independent Task Force Special Report, Issue 13, 2008.

28 C L Drifmeyer, ‘Overview of Overseas Humanitarian, Disaster and Civic Aid Programmes’, Military Medicine, Vol. 168, No. 12, 2003, pp. 975–80.

29 Guidelines for Humanitarian Operations, Sphere Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Disaster Response, 4th edition, October 2003, <www.sphereproject.org> accessed 27 August 2006.

30 Drifmeyer, ‘Overview of Overseas Humanitarian, Disaster and Civic Aid Programmes’, pp. 975–80.

31 Neuhaus and Bridgewater, ‘Medical Aspects of Complex Emergencies’, pp. 56–72.

32 North Atlantic Treaty Organisation, AJP-4.10 (A) – Allied Joint Medical Support Doctrine, 2006.

33 Personal correspondence, Lieutenant Colonel S J Neuhaus, Colonel D Jenkins, USAF, Director, Joint Theatre Trauma Registry Systems Program, May 2008.

34 Neuhaus and Bridgewater, ‘Medical Aspects of Complex Emergencies’, pp. 56–72.

35 D Saul, ‘3rd Line CSS & Adaptive Campaigning’, unpublished essay, 2008