Abstract

The purpose of this article is to explain some of the various types of incentives that can be awarded within sustainment contracts and that will benefit both the contractor and the client—in this case, the Australian Defence Force (ADF). This article describes a variety of financial and non-financial incentives including those currently employed by the ADF in its Performance Based Logistics (PBL) contracts.

Introduction

A number of Australian Defence Force (ADF) outsourced logistics contracts have shown signs of a paradigm shift in focus from functional to outcome-based performance. At the same time, aligned financial payments have shifted from a cost-based to an outcome-based requirement. Traditionally, logistics requirements have been outsourced and remunerated with contractual agreements involving payments on a timely basis for functions undertaken. Performance Based Logistics (PBL) is based on the notion of rewarding outcomes rather than the traditional functional inputs. Although this form of incentive-based contracting represents a fairly new concept, it has been endorsed by the ADF and is expected to gain prominence in logistic support contracts in the future. The current situation appears to involve a separation between the acquisition of a capability and the sustainment of that capability over its useful life. The associated contracts are referred to as ‘acquisition contracts’ and ‘support’ or ‘sustainment contracts’ and, while there are compelling arguments for the integration of sustainment contracts with acquisition contracts at the time of the development and research of the relevant capabilities, the separation of the two appears set to continue. This article reflects that trend, separating the two types of contract and concentrating on the financial and non-financial incentives associated with the sustainment component of defence contracts.

It has long been argued that, by working closely together, companies and their suppliers and logistics providers can create highly efficient and effective supply chains.1,2 Failing to collaborate may, in fact, result in the distortion of information as it moves through a supply chain. This distortion leads, in turn, to costly inefficiencies as demonstrated by the notorious ‘bullwhip effect’ which results in excess inventories, slow response, and lost profits, all through a lack of close relationships.3,4 Through more open, frequent and accurate exchanges of information and the ‘right’ performance incentives, many of these problems can be eliminated. The new ADF performance-based sustainment contracts are based on performance-based logistics metrics and are clearly aimed at finding the ‘right’ performance incentives to encourage continuous efficiencies from their outsourced providers. These contracts will be referred to as PBL contracts throughout this article.5

Brief Background

The US Defense Force was a driving force in implementing performance-based logistics contracts. This first section of the article will provide a brief background on the use of PBL contracts within the US Department of Defense (DoD). The 2001 Quadrennial Defense Review Report provided the impetus for the US Department of Defense’s logistics processes and procedures to move to adopt a needs-based concept.6 This capability-based logistics approach focused on improving visibility into supply chain logistics costs and performance and on building a foundation for continuous improvements in performance. PBL was regarded as a means of optimising the productive output of the overall military supply chains. A review of private sector best practices used in managing supply chain partnering relationships by the US DoD in 2003 found PBL to be a best business practice. Since this review, the Under Secretary of Defense (Acquisition, Technology and Logistics) has lent strong support to the use of PBL contracts. The subsequent DoD Directive 5000.1 entitled ‘The Defense Acquisition System (dated 12 May 2003), stipulated mandatory policies and procedures for managing all acquisition programs including the implementation of PBL strategies.7

Performance-based contracting has spread throughout the health and pharmaceutical, fuel and consumer industries, all of which focus on required outcomes.8 Typically, all performance-based logistics contracts are based on ‘incentivising’ the performance of the outsourced contractor. For the ADF logistical contractor, PBL is linked to RAM (reliability, availability and maintainability) of large platforms and, again typically, most risks are transferred from the ADF to the contractor for the support and sustainment of equipment. This concept of risk transfer to the contractor is common across all industries using performance-based contracting.

Definitions

PBL covers the purchasing of any sustainment process to ensure that the process is integrated, affordable and designed to optimise any Defence Systems Readiness. PBL contracts state that the provider is held accountable for the delivery of customer-oriented performance requirements such as reliability improvement, availability improvement and supply chain efficiencies. The performance is outcome-based and employs metrics such as readiness, availability, reliability and sustainability of readiness.

PBL provides an alternative logistics support solution. It transfers the logistics support to an outsourced supplier for a guaranteed level of performance at the same cost—or less—than providing the support itself. The performance changes from input-based performance (shortened turnaround times in terminals, for example) to outcome-based performance. The incentives in a PBL contract are associated or tied to the performance levels of the outcomes required. This concept follows the concept of diagnostic maintenance in which an engine is only repaired or scheduled for maintenance when the unit demonstrates that it requires repair or maintenance. Thus repairs or maintenance are not performed on a regular basis in a preventative schedule, but rather in accordance with a demand-based schedule. Maintenance only occurs when it is required. Although this form of contract is still linked to an input-based concept in that the part is only repaired when it is broken or needs maintenance to maintain its level of reliability, the contract will stipulate a required level of reliability not a required level of repair or maintenance. The complete outcome-based performance metric will be associated with the level of reliability of the equipment for use, rather than the regularity or quality of the maintenance performed as demanded diagnostically.

Some of the common areas in which PBL contracting is used include transportation and inventory management. In its most integrated form, PBL should fully automate a resupply system. Usage rates and inventory levels at the customer outlets would be used to maintain a stock level, removing the requirement for procurement orders. The repairable item management system, obsolescence, and configuration management systems would all feed into the overall resupply system to provide real time visibility of the resupply flows.

The key differences between the traditional and PBL inventory management system are illustrated below:

Table 1. PBL versus traditional inventory management (British Aerospace PBL)

| Philosophy | Critical Element | Role of Provider | Results | |

| Traditional | Inventory-based | Lowest prices | Manage supplies |

Focus on supply availability Problem solving by stocking more inventory |

| PBL | Performance-based | Best Value | Manage suppliers |

Focus on customer service and readiness Problem solving by buying response time, quality and reliability |

Financial Incentives

There are many forms of financial remuneration suitable for use as incentives or rewards for performance. Ideally, financial incentives should be tied into a contract that links them to performance. The long-term nature of the partnership requires a mutual recognition of needs. PBL contracts may evolve as the capability support system matures. The most beneficial result from the contractors perspective is the consistent revenue stream. This permits the contractor to maintain business viability while attempting to win the proffered performance incentives. As a consequence, most PBL contracts will be written on a cost plus basis of some sort. This means that the contractor will always recoup the costs involved in producing the service regardless of the performance targets. While there are many types of cost plus contracts, the common ones include:

- CPFF (cost plus fixed fee)

- used when cost and pricing risk is maximum

- basically reimburses contractor for level of effort work.

- CPIF (cost plus incentive fee)

- used early in program when metric baseline is immature

- primarily oriented towards cost (allowable and targets)

- can include some performance incentives other than cost

- CPAF (cost plus award fee)

- used when subjective assessment of contractor performance is required (i.e. customer satisfaction)

- usually used in combination with CPIF.

CPFF provides a non-negotiable fixed price. Although the base price is not adjustable and thus easy to administer, the overall price does include some proportion of profit margin.

CPIF provides a fixed cost component and a performance-oriented incentive component. Like CPFF contracts, the aim is to cover the cost base (thus maintaining the consistent revenue stream for the contractors) as well as ‘incentivising’ for performance. The performance metrics used are tied to outcome requirements.

CPAF includes the cost component plus a base fee for performance, but this performance fee is fixed. The award fee is a ‘yes/no’ element based on judgment of some level of subjective performance such as customer satisfaction. These are often used when the cost and resource baseline is fully mature and pricing risk is minimal. These contracts place the highest risk on the contractor and the lowest risk on the client.

PBL contracts can fall into any of these types, although generally the objective is to work towards a fixed price contact. Fixed price contracts are self-motivating in that the more efficient the contractor becomes, the lower the costs incurred, implying a higher profit margin. Thus, in the long term, PBL contracts aim to purchase defined outcomes at a defined price (see Table 2). Typically, this depends on the degree of pricing risk inherent in the support costs. Contracts in a complex capability support system may progress through a series of phases.

Table 2. Types of performance contracts

| Firm Fixed Price | Cost Plus Incentive Fee | Cost Plus Award Fee |

| Price not adjustable | Price has allowable costs plus incentive fee | Price has allowable costs, base fee and award fee |

| Specifies target price, i.e. price ceiling plus profit | Incentive fee based on metric target achievements | Base fee does not vary with performance |

| Maximum risk on contractor | May include cost gain sharing (comparing actual to target cost and sharing the savings) | Award fee is based on subjective evaluation of performance |

| Minimum administrative burden on all parties | Established relationships made between fees and metrics | Award fee payments are unilateral |

| Requirements are well defined | Subjective requirements, e.g. customer satisfaction | |

| Establish fair and reasonable pricing |

Performance-based sustainment contracts can develop towards the final fixed price plus awards structure through a number of interim contractor support stages. For example, during the initial pre-operational state of the capability and early production periods where products and testing and initial spares and maintenance training occurs, a cost plus fixed fee contract will be set in place. As the costs stabilise, a transition contract will evolve towards a cost plus an incentive or an award fee basis. This interim contract will remain in place while the costs and resource baselines are tracked and refined. Finally, in the third or final phase, the contract will change/evolve into a fully fixed price plus award fee contract. Before a CPAF contract can evolve, all the costs and resource baselines need to be well documented, risks lowered and both parties should define incentives and performance outcomes with a high degree of confidence.

How the Financial Incentives Work

Financial incentives are typically based on a sliding scale of achievable performance targets. The performance metrics in PBL contracts are outcome based. These incentives relate to the ‘on time in full’ (OTIF) metric of all logistics suppliers. They receive the full payment if the total order is fulfilled and delivered in the right location at the required time without damage. In the fast moving goods retail industry, delivery windows are often set so that the full order must be delivered within set time windows. Heavy penalties are applied if the delivery occurs outside these timeframes. In PBL contracts utilised by the ADF, the emphasis is placed on rewarding good performance rather than imposing penalties for poor performance. While poor performance is not rewarded, penalties are not applied unless a series of poor performances warrants termination of the contract.

In a typical example, a PBL metric may be a non-mission capable supply (NMCS) which measures the percentage of time that a system is not mission capable due to the lack of a critical part. Assume that the typical percentage target is 5 per cent (on a per annum basis). Thus the defence capability is mission ready for 95 per cent per year. Correspondingly decreasing incentives at 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 per cent would occur and the contractor would earn no incentive if the non-mission capable supply levels reached 11 per cent.

Table 3. PBL metric for non-mission capable supply

| NMCS% | 5% | 6% | 7% | 8% | 9% | 10% | 11%> |

| Award Fee Points | 100 | 80 | 60 | 40 | 20 | 10 | 0 |

In this case the contractor would receive the full performance award fee if the system was available 95 per cent of the time during the year. Note the consistent relationship between the 1 per cent changes responding to a 20 per cent change in award fee points. The calculation of the adjusted performance result and the corresponding award points or incentive payments need not be consistent. For example, payment of a reward may only occur if the contractor provides a greater than 100 per cent score. On the other hand, a penalty maybe incurred if a greater than 100 per cent service is provided, for example, the provision of additional aircraft which may, in fact, be a superfluous service as there are no pilots available to fly them. Over-servicing in such instances is inefficient and wasteful. Similarly, the rewards may drop dramatically after a set acceptable level of performance. For example, after an NMCS percentage of 6 per cent, award fee points may drop to twenty, while at 7 per cent, no incentive will be earned. The ‘bands’ of incentives may be consistent or may drop rapidly depending on the importance to the customer of the performance outcome.

Fixed Price Contracts

The overall objective of most contractors is the achievement of a fixed price contact. Under fixed price contracts, the contractor is motivated to continuously improve efficiency, lowering costs and thus earning a higher profit. PBL contracts aim to purchase defined outcomes at a defined price. Outsourced suppliers are motivated to procure super reliable parts and perform high quality repair and maintenance as they will benefit from cost reductions resulting from fewer repairs over the longer term.

Benefits of fixed price contracts generally include:

- contracts are inherently cost controlled

- no payments are made unless the goods/services are provided

- forecasting and trend planning is easier to manage

- financial expectations are less uncertain.

Non-Financial Incentives

Typical non-financial recognition schemes involve certification of awards and achievement levels, letters of commendation, certificates of achievement and ‘best supplier of the year’ awards.9

Contract extensions can be written into PBL contracts in recognition of satisfactory performance. Contract extensions can merge with upgrade priority systems giving priority considerations to existing high performance contractors. While this is a discriminating factor, it acts as a strong incentive to perform well in one contract when there is a possibility of gaining all the upgrade contracts associated with the capability in the future.

Gaining and building reputations is an elusive performance indicator. A sound reputation is one of the strongest competitive advantages that a firm can secure. Understanding the performance gap between a contractor’s level of service and the best in class practice can lead to the building of an enviable reputation. Consequently, one of the strongest incentives that a firm can be given is the possibility of becoming the best in class within its industry. The publication of logistics operational service levels and KPI achievements, especially by a prestigious defence department, will enhance the reputation of any service provider.

Benchmarking of supplier and maintenance logistics providers against contractually defined performance levels is an elusive but extremely powerful incentive.10 Best-practice status in an industry is difficult to confirm.11 As distinctions between ownership and control become blurred, supply chains become increasingly twisted although, surprisingly, some global manufacturing operations achieve a remarkable degree of transparency. For example, Cisco Systems, which recorded sales of $28 billion in 2006, does not own the vast majority of factories making its products; yet the performance of these outsourced factories and distribution providers is recognised as one of the most agile, adaptable and speedy in the world. Similarly, Boeing began its development of the 787 aircraft by seeking its suppliers’ advice.12

TQM is Alive but still Developing

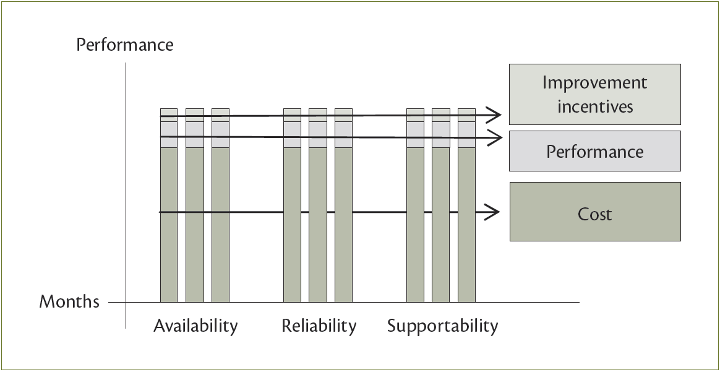

It is possible for contractors to gain an incentive payment if all performance awards have been achieved over a set period of time. For example, if the top performance of 5 per cent non-mission readiness is achieved for all systems, or if the top performance is achieved for every performance metric, then an additional or bonus payment is awarded for achievement effort. This is where the total quality management (TQM) concept of continuous improvement is currently being applied in PBL contracts with the ADF. The TQM philosophy states that each firm should continually strive to improve its efficiencies. This will benefit society through reductions in waste, higher productivity and greater effectiveness and quality of service. Consequently, there is an option for contractors to achieve over and above their cost plus performance awards if excellent performance is achieved in all outcome metrics over a given period of time such as three months. If these incentives are offered, the contractors will be encouraged to continually improve their performance via the fixed cost component, the monthly award achievements and an aggregated bonus for consistency of performance. It is debatable whether these improvement incentives should be applied on a sliding scale or applied differently for different metrics or even applied equally as illustrated in the diagram below.13

This diagram illustrates that, over the three month period, the contractor reached the full performance requirement consistently for each of the three metrics of availability, reliability and supportability. In achieving these targets, the contractor received performance award payments and also received the extra reward labelled ‘improvement incentives’ because of the consistency of the performance levels.

In this case, the gains may lead to a review of the performance targets or a movement from one type of contract to a more fixed price form of contract. Regular reviews of performance achievements are necessary to continuously improve the relationship and the performance of both parties. Gain- or loss-sharing contractual models require periodic reviews to establish the extent of the sharing of the risks

Diagram 1. Cost plus award with improvement incentive payments

and rewards of cost changes during any period. Profit or gains in the one period are affected by cost performance in the previous period and, as such, any cost overruns can result in reduced profits in the next period. Consequently, all gain- or loss-sharing incentives will have a lagged effect.

Benefits to the Custom

Both parties benefit from PBL contracts in that both experience a goal convergence. The overall goal of the customer involves a drive for best results from the provision of logistical support and sustainment in a cost-efficient and most effective manner. The goals of the contractor via the self-motivating drive for profits include cost efficiency in all aspects of the logistical provision at the operational level, thus driving down costs and increasing the contractors profits. The goal of achieving ‘best practice’ will earn the contractor a sound reputation that will stimulate the growth of the firm. In this way, the goal convergence of both parties is achieved.

The ADFs preferred core outcomes include:

- systems readiness

- light footprint

- mission success

- assurances of supply.14

From the customer perspective, the logistical benefits include:

- high level of support for its capabilities

- best value sourcing for inventory, infrastructures, maintenance and service functions

- reduced cycle times, inventory, total ownership costs and improved reliability and obsolescence management problems

- payment for results only, not activity

- transfer of risks.

Benefits to the Contractor

The primary goals of the ADF are generally outcome-based and expressed in terms of mission success measured by readiness, light footprint and assurance of supply. The main goals of any commercial contractor, however, lie in profit maximisation, good returns on investment and overall growth. While these two diverse sets of aims reflect the limited likelihood of goal convergence, the processes of achieving these goals are, in fact, quite similar.

The contractors means of performance evaluation includes comparisons with previous records so as to improve productivity and reduce cost baselines, and comparison with or benchmarking of competitors so as to remain competitive and achieve the status of order-qualifiers and order-winners in the future. In the current environment, successful firms must be innovative, attain a sound knowledge base and recruit high-quality personnel, be medium risk-takers and offer superior quality products or services.15 Logistic providers must have an intimate knowledge of the supply chain in which they operate.16 Capacity of any given supply chain is measured by the flow of physical, information and financial movements over a given period of time. The main flow restrictions concern capacity and utilisation of physical flows through nodal points along the chain. Throughput flow is typically less than designed capacity; utilisation is the proportion of this designed capacity that is actually used. In PBL contracts, the former is more commonly measured although the latter is more useful for surge considerations.

The contractor has to assess the risks of utilisation of the total supply chain. This assessment implies the maintenance of a high level of detailed knowledge on the part of the contractor to equip them to continue to achieve the desired goals of competitive advantage, profit maximisation, successful operations and growth.

The financial goals of the contractor are expressed in terms of the return on investments (ROI), the direct product profit ratios (DPPs), the customer profitability matrix (CPM), the market value added (MVA) of any contract and the economic value added (EVA). Analysis of these inputs allows the profit after tax minus the true cost of capital employed to be calculated.17,18

The contractor’s assessment of productivity will include total productivity, which is measured by the total throughput divided by the total resources used or partial- or single-factor productivity measures, which might include labour, equipment, capital or energy productivity. Contractors generally aim for overall total productivity improvements that cover the service/cost trade-offs. In this respect, PBL contracts tend to obstruct the contractors’ objectives, as PBL contracts reward only the service levels regardless of costs to the contractor.

Challenges

The main challenges include:

- developing a collaborative environment among all stakeholders

- overcoming organisational transformation issues

- effectively implementing PBCs in highly regulated environments

- if the trends in globalisation and services continue, developing effective policies and practices that will allow the ADF to benefit most from the future globally based industrial base

- identification of the changing risks.

Challenges that are emerging from the US DoD:

- switching paradigms at the congressional and senior leadership level with respect to money

- overcoming organic resistance to implementation of PBL on a broader scale (stovepipe)

- long-term contract strategy options

- reduced competition

- effective metrics to ensure value gained

- fear of loss of organic capability (Title 10)

- corporate survivability

- accurate reflection of ‘as is’ vice ‘should be’.19

Some of these challenges (with the exception of the Title 10 requirements) will also be evident in the Australian supply environment.

More detailed analysis of challenges reveals a number of issues. One key challenge lies in maintaining a continuously improving performance level. PBL contracts do not offer the traditional penalties for non-delivery; rather there is simply no reward. The 3PL or contractor does not pay a penalty for faulty performance, nor does the customer pay a performance incentive. The challenge is to level the fixed cost component to include only partial covering of the opportunity costs, thus indicating to the contractor that performance will have to improve for the contractor to viably remain in the contract.

The timing of the change of contractual phases is often difficult to gauge. Is the contractor taking too long to sort out the repairs schedules or bed down the maintenance schedules? With three or four different phases in a PBL contract associated with a large capability, it is difficult to achieve maximum improvements in the shortest possible time so as to attain the goal of a fixed price PBL contract.20

Non-financial awards that are fair and equitable in a market place so as to not incur high barriers of entry but, rather, stimulate best in class including innovation and entrepreneurship, are difficult to achieve across total supply chains. The long-term nature of lifetime partnerships for the lifecycle of the logistics system are certainly enviable contracts to achieve, but must not encourage inertia.

Innovation take-ups and continuous improvement once the firm has achieved the fixed price phase may also be difficult to motivate. The self-motivation associated with fixed price contracts is often not rewarded sufficiently and the contract develops into a ‘cash cow’ for the contractor while other more competitive and rewarding contracts are pursued. To prevent inertia pervading the fixed contract involving a long-term partnership, other rewards must be offered so as to motivate the firm to continue to strive to be the best within the industry in the absence of competitive force. Metrics such as industry standards do not stimulate companies to strive for greater competitive advantage in an industry. Competitive standards ensure that the contractor matches the average performer in the industry not the most competitive performer in the industry—simply the order-qualifier, rather than the order-winner.

Legal concerns may be aroused over the economic impacts and competitive barriers that can be erected with sole sourcing and sole support contracts. Unfair competitive advantage may attract the scrutiny of the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) over time, particularly as upgrades to capabilities may provide an unfair advantage in any tendering of logistical support to the existing contractor. As the industrial base expands globally, however, the ACCC may lose its power to control and protect Australian industries. In the aerospace industry, for example, the global giants of Lockheed Martin and Boeing compete fiercely for long-life contracts for their equipment and planes. While this is currently a strong oligopolistic market, the legalities look set to become complex with the increasing incidence of mergers and takeovers within the dynamic supply chain industry. Contractual terms and conditions need to increasingly clarify such complexities as the contracts extend their web of terms and conditions.

The identification and establishment of metrics should be clear and measurable. The metrics for reliability, availability and maintainability must be equitable over a number of capabilities. The outcome-based metrics focus on customer satisfaction rates which need to be clearly defined beyond the intangible of perception versus actual satisfaction.

For PBL contracts to work successfully over time, a team approach is required; one of the greatest challenges in this approach is the ‘people factor’. The formation of the team and stakeholder identification and interest is difficult to achieve over the changing life of a large capability. Clarity of roles and responsibilities will recede as the contract shifts through the lifecycle phases and as performance-based agreement evolves in line with upgrades and maintenance requirements. Continuous and open communications must be effected at a personal level as well as at an automatic level. The prevention of inertia is difficult to achieve over long periods of time and, although the continuous improvement incentives will assist in preventing inertia to some extent, this should be offset by the continuous flow of revenue.

Conclusion

PBL contracts are typically long-term, focusing on financial rewards as incentives to improve performance that can develop over phases. PBL contracts are, in fact, continuing to evolve. They are becoming more complex with the inclusion of options for gain- and loss-sharing and more detailed ‘health’ indicators.

PBL contracts in the ADF continue to evolve given the need to include performance metrics, such as rewarding light footprints and accurate breakdowns so as to ensure ‘mission success.’ Often, mission success relies on using capabilities differently in different missions. Incentives to cover these forms of variegates have yet to be fully developed.

Financial and non-financial incentives are, however, being successfully employed. There is evidence that PBL contracts are providing better quality service and this is expected to continue in the future.

Having clarified a number of the financial and non-financial incentives currently used, additional research should focus on analysis of motivation within fixed cost contracts. Further research is needed to explore the rewards for innovation or the rapid and efficient utilisation of innovation within the increasingly dynamic supply chain industry.

Endnotes

1 C J Corbett, J D Blackburn and L N Van Wassenhove, ‘Partnerships to Improve Supply Chains’, Sloan Management Review, Iss.40, Summer 1999, pp. 71–82.

2 L H Harrington, ‘Logistics assets: Should you own or manage?’, Transportation & Distribution, Vol.37, Iss.3, 1996, pp. 51–4.

3 J L Lee, V Padmanabhan and S Whang, “The Bullwhip Effect in Supply Chains’, Sloan Management Review, Iss. 38, Spring 1997, pp.93–102.

4 S K Paik and P K Bagchi, ‘Understanding the causes of the bullwhip effect in a supply chain’, International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, Vol.35, Iss. 4, 2007, pp. 308–24.

5 Performance-based contracting (PBC) is the term applied by the Defence Materiel Organisation within the ADR The US DoD uses the term PBL to describe the concept of sustainment contracts, which tend to be separate contracts from those acquisition contracts presently utilised in ADF contractual arrangements. The essential element is that performance-based logistical outcome measures are used as the basis for financial payments under lifelong support or sustainment contracts for a military capability.

6 In 2001 the US DoD mandated that PBL be considered for the support for all new weapons systems.

7 H J Devries, ‘Performance Based Logistics—Barriers and Enablers to Effective Implementation’, Defense Acquisition Review Journal, December 2004-March 2005, Defense Acquisition University, California, p. 244.

8 P Danese, P Romano and A Vinelli, ‘Sequences of improvement in supply networks: case studies from the pharmaceutical industry’, International Journal of Operation & Production Management, Vol. 26, Iss. 11, 2006, pp. 1199–222.

9 S Geary and S Zonnenberg, ‘What it means to be best in class’, Supply Chain Management Review, Vol. 4, Iss. 3, 2000, pp. 43–8.

10 K L Choy, K H Chow and W B Lee, ‘Development of performance measurement system in managing supplier relationship for maintenance logistics providers’, Benchmarking: An International Journal, Vol. 14, Iss. 3, 2007, pp. 352–68.

11 L Laiede, ‘True measures of supply chain performance’, Supply Chain Management Review, Vol.4, 2000, pp.25–8.

12 -- ‘A Survey of Logistics’, The Economist, 17 June 2006, accessed at <http://www.economist.com/surveys/displaystorycfm?storyid_id=7032165

20 Varma et al., ‘Implementing supply chain management in a firm: issues and remedies’, pp. 223–43.