Abstract

As the Australian Army continues to deploy troops to operations across the globe, questions are being asked both within and outside the Army as to why certain forces are being deployed. This article explores the role of the Royal Australian Infantry, and suggests changes that would increase options for its deployment.

Armies do not win wars by means of a few bodies of super-soldiers but by the average quality of their standard units... The level of initiative, individual training, and weapon skill required in, say, a commando, is admirable; what is not admirable is that it should be confined to a few small units. Any well trained infantry battalion should be able to do what a commando can do; in the Fourteenth Army they could and did.

- Field Marshall The Viscount Slim1

Introduction

The success of any military mission can only be measured by how well it has achieved its aims, and at what cost. By these measures, therefore, the involvement of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) in Iraq and Afghanistan can only be seen as a resounding success. The survivability and lethality shown recently by the Security Task Group attached to Reconstruction Task Force 3 (RTF 3) is testimony to this. We should take care, though, to ensure that this very success does not blind us to the nature of the threat which we have faced, nor should we derive false conclusions from the experience. If Australian forces had been tasked to counter the insurgencies in a district of downtown Baghdad, Basra, or Helmand province, they would have undoubtedly faced a far more torrid existence, casualties would have been almost inevitable, and military lessons learned would have most likely been different. Instead, the operations faced by Australian conventional forces over the last ten years have been defensive, or at the most protective, in nature and therefore should be examined in that context. It would be equally misleading, however, to assume that involvement in future conflicts will be of a similar nature and that conventional forces will not be required to undertake offensive operations and tasks similar in nature to those that our sister units in the US, British and Canadian armies are currently undertaking.

To that end, there is a growing sense of frustration within the ranks of the Infantry that regular infantry units are only receiving perceived second rate operational taskings, while the government and Army hierarchy seem to favour Special Forces for deliberate offensive operations and tasks. This is causing a double dilemma. While there is little doubt that Australian Special Forces have performed to a standard that has made Australia a valued partner in the ‘War on Terror’, they are increasingly finding themselves straying from undertaking operations of a strategic nature which are their raison d’être, into more conventional operations because as a military force they are a proven quantity. However, this has the consequence that while the Special Forces community is finding itself stretched by back to back tours, Australian company and battalion commanders of regular infantry units are missing an excellent opportunity to gain contemporary operational experience. It is this experience that the Infantry, and indeed the Army, needs their commanders to take with them as they progress into influential, higher command positions within the Army. At a lower level the diggers, NCOs and junior officers are starting to question the Infantry’s role and their part in it, which is having a tangible effect on morale. Whatever the reasons for this reluctance for Australia to deploy its regular infantry to conduct offensive operations, the Infantry can seek to address it by ensuring that it is a more attractive option for its military and political masters. Deployment of regular infantry would enable Special Forces to revert to their doctrinal role of shaping the environment at the strategic level while the Infantry conduct offensive, defensive and security operations.

This article seeks to highlight three ways in which the Royal Australian Infantry can seek to make itself a more attractive option for deployment:

a. the swift adoption, and enhancement, of structural changes based on Infantry 2012,

b. the development of the Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR) Battlefield Operating System (BOS) within the infantry battalion,

c. the insistence on a more logical training and deployment cycle.

Infantry 2012 Structural Changes

The Infantry fire team represents the basic building block for the modular Infantry unit. It provides for the adoption of the modular concept to meet the demands of future operations within the complex warfighting construct.

- LWD 3-3-7 Employment of Infantry2

The proposed adaptation of Infantry 2012 is probably the most seismic event in the evolution of the Australian Infantry since the end of the pentropic experiment in 1964. It is therefore a controversial move, and has caused a great deal of debate, not only within the Infantry itself but within the Army as a whole, and at all levels. The important point which must be understood before Infantry 2012 is implemented is that the present system is not broken. Indeed it has performed admirably for a generation of soldiers. So the question then inevitably raises itself, ‘if it isn’t broken then why fix it?’ The answer is that while the old system works adequately in most conditions, the new structure under Infantry 2012 is so much better. As the nature of both high-intensity and counterinsurgency warfare has evolved, so the Infantry’s need for a structure to suit all phases of war has become more apparent. In tandem, as technology has changed, so has our ability to create smaller groups of soldiers that are more lethal and usable, and yet more survivable, than ever before. The introduction of Personal Role Radio and the Global Positioning System, for example, has meant that sections no longer necessarily need to be all in constant sight of the section commander to receive instructions from field hand signals. The information networking of the Army is now present down to individual soldier level and is set to increase in its scope as technology improves. To that end, the modular approach incorporated in Infantry 2012 gives both greater flexibility, in that it gives the commander the ability to reorganise his force to meet the changing operational requirements he is faced with, and greater adaptability, which for the purposes of this article means the speed with which the commander is able physically to reorganise and reorientate to the changing threat. This theme is elaborated below.

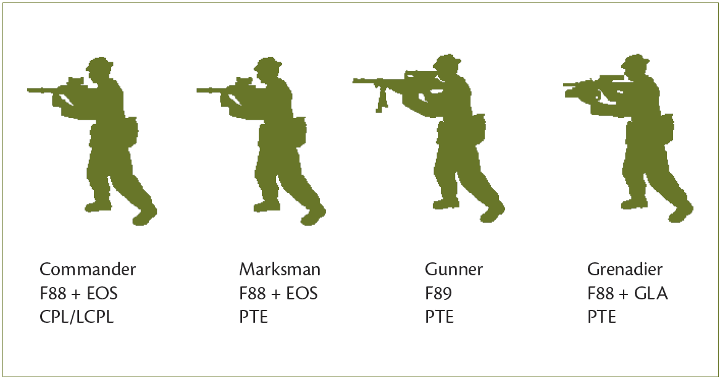

The structure of the infantry battalion is laid out within the Australian Army publication, LWD 3-3-7 Employment of Infantry. This publication clearly sets out the four-man fire team, as illustrated in Figure 1, as the basic block within the rifle company. It can be seen that a four man fire team comprises a commander, grenadier, gunner and marksman. A section is formed from two identical fire teams, one of which is commanded by a corporal, and the other a lance corporal. This is a departure from the traditional infantry section of nine, comprising of scout group, gun group and rifle group. There are many who will debate whether the tried and tested old system needs to change at all, but it should be remembered that the inherent strength in the new system is its flexibility, and thus its adaptability. Mathematically, four is an incredibly versatile number. A section of eight can easily be turned into a multiple of twelve with the addition of a third fire team. In addition, because of mirrored weapons systems, each fire team is able to assault or suppress depending on the situation. No more awkward rebalancing of groups by the section commander under contact because the rifle group happened to be in the ideal fire support position for his gun group. More importantly, in the evolving nature of combat team orientated operations, fire teams of four can more readily be combined with other assets, especially protected mobility assets, to increase combat capabilities. The Bushmaster when used as a transport vehicle is designed to carry a light infantry section of eight, for example.3

Figure 1. The Fire Team

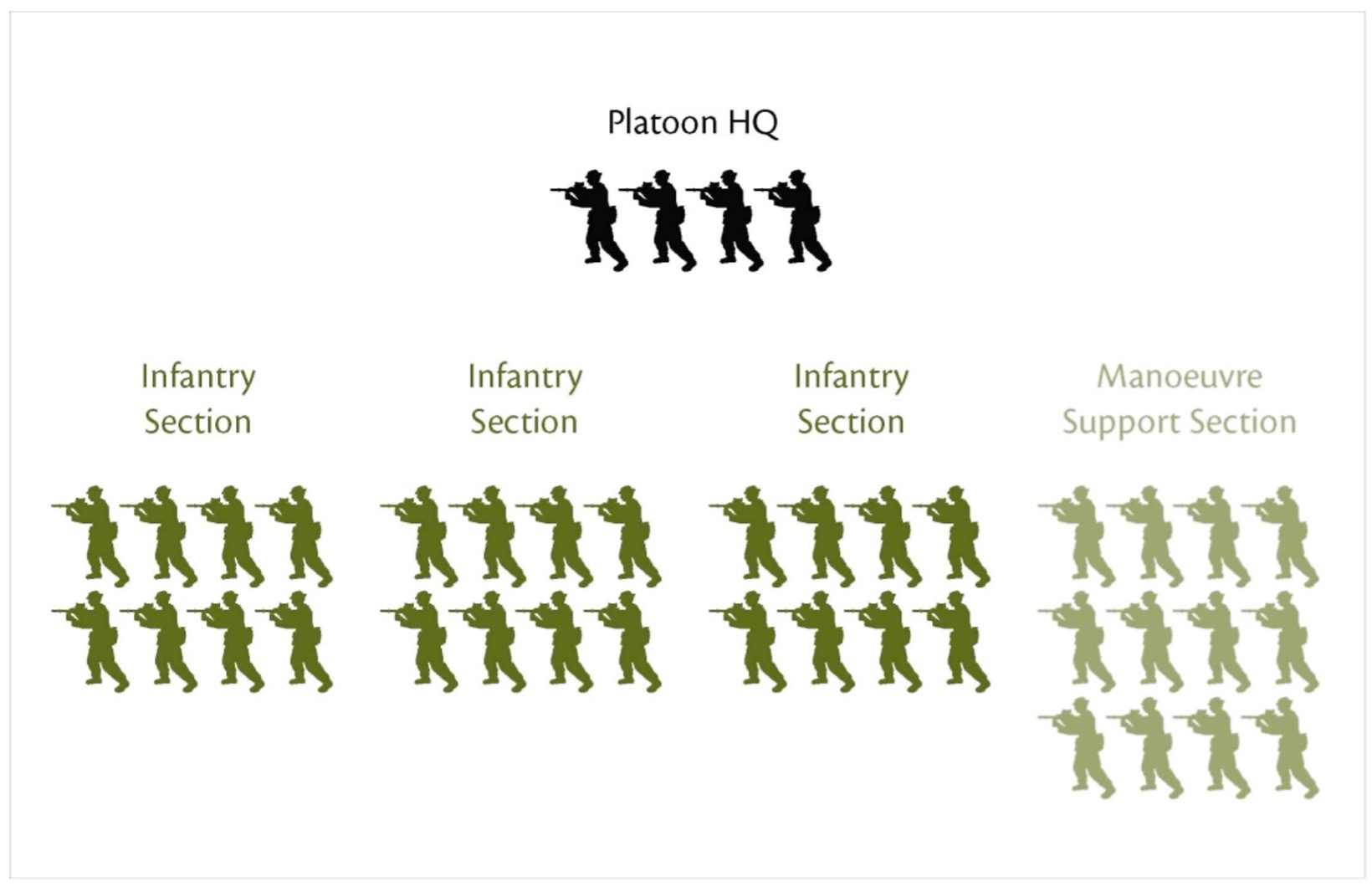

The big change at the platoon level comes with the creation of the manoeuvre support section (MSS). Within LWD 3-3-7 each light infantry platoon contains a manoeuvre support section, consisting of three teams of four men. Each team consists of a commander, marksman, grenadier and machine gunner, and the section’s purpose is to operate and tactically employ precision direct fire, area suppression, and multipurpose weapon systems to reduce or defeat enemy fortifications, bunkers and armoured vehicles.4 In essence, and at its most basic, this means that at the platoon level there are three light role MAG 58s and three specifically equipped marksmen. Together these will be able to give suppressive fire which will increase the platoons effective influence out to 1100 metres on the battlefield. There is also discussion as to whether there should be a mixture of machine guns and anti-armour weapons depending on the tactical situation, or even the addition to the MSS arsenal of a medium-range automatic grenade launcher. Again the strength in this system is its modularity. The company commander is able, depending on the tactical situation, to brigade these manoeuvre support sections together into a company manoeuvre support group, commanded by a company weapons sergeant who works in company headquarters, to allow him to fix the enemy while he manoeuvres his assaulting platoons. Not only does this allow both platoon and company commanders to have the required forces to truly achieve the principles of ‘find, fix, and finish’;, but the modular concept allows for alternate structures with varying equipment to be made dependent on the task, threat and environment. This then fulfils both the requirement for an increase in the survivability of a deployed land force by increasing combat weight and firepower, and makes the company more capable and adaptable over a wider range of likely tasks, as demanded by the principles behind the philosophy of the Hardened and Networked Army.

Figure 2. The Light Role Infantry Platoon

Infantry 2012 is a significant structural change for the Infantry, but its advantages over the status quo lie in its flexibility, modular structure, increase in lethality through organic firepower, and the ability to rapidly reorganise to face a changing threat. It is true that Infantry 2012 has not been welcomed with open arms by all, even if it does formalise what in effect has been adopted by troops on the ground on operations for the last few years. Suffice to say, however, that if the Infantry as a Corps is delaying implementation because it is arguing internally about whether a section should comprise eight soldiers or nine, or debating what weapon system a marksman should be equipped with, then it is missing the point and doing its soldiers a disservice. The strength of the changes laid out in Infantry 2012 is in its modular approach, enabling commanders the flexibility to regroup at short notice for mission specific tasks. Indeed, both the infantry section and the infantry platoon as laid out in Infantry 2012 possess more organic firepower than any Australian regular infantry section or platoon before it. Study of the Order of Battle (ORBAT) of a Commando company from 4 RAR, although itself subtly different from Infantry 2012, and their experiences on operations, shows that the adoption of a modular, highly potent approach which utilises organic combined effects and synergies works, and that this inherent flexibility gives greater capability across a range of operational taskings. Moreover, by delaying implementation of Infantry 2012 the Infantry are sending a signal to the rest of the Army, and its military and political masters, that it is not yet ready to face the challenges of the modern battle space. While this image remains, many fear that the Infantry will continue to find itself escorting federal policemen to polling booths rather than engaging and defeating the enemy in close combat.

Increase in ISR BOS Capability

Our greatest weakness now is the lack of early and accurate information of the enemy’s strength, dispositions and intentions. For lack of information an enormous amount of military effort is being necessarily absorbed on prophylactic and will o’ the wisp patrolling.

- General Sir John Harding, Malaya, 19505

Now, more than at any time since 1945, the ADF is faced with the dilemma of having to be always prepared for the possibility of interstate war, combined with the probability of being involved in intrastate conflict. As the nature of operations has evolved since the end of the Cold War, so have the military-academic attempts to pigeonhole contemporary conflict into a catchy phrase. However, regardless of whether it is described as ‘3-Block War’, Fourth Generation Warfare (4GW), asymmetric warfare, complex warfighting, or ‘war amongst the people’, what modern conflicts all have in common is the dispersion of enemy combatants into the civilian population. They have learned the hard way how to avoid being targeted by modern military technological capabilities. This is not just during counterinsurgency campaigns. Even in the latter stages of the invasion of Iraq in 2003, conventional Iraqi Army troops were dispersing amongst towns and villages to increase their survivability against a technologically superior, largely conventional enemy which enjoyed air supremacy. So the Army, and the Infantry in particular, needs to increase its effectiveness in operating in a dispersed battlespace while still maintaining the ability to conduct high-intensity, interstate warfighting.

This emptying of the battlespace and dispersion of the enemy will ensure that the ISR BOS, which performs the ‘know’ combat function, will continue to become increasingly important. The ability to find the enemy and then fix them in time and space (i.e. to track them) is paramount to success on the modern battlefield. Indeed, with politicians and their electorates being fed a constant live-feed from our operational theatres by a 24-hour media, the accuracy and timeliness of the ISR BOS is likely to become the mission critical aspect of any commander’s plan.

For the Infantry to become a more attractive option for combat deployments, it needs to focus on what infantry battalions contribute to the ISR BOS. At present this is based on the reconnaissance and surveillance platoon and the intelligence cell, (not withstanding that all manoeuvre elements contribute to the ‘know’ function in their own right). Both these elements are at present located in a support company. The recommendation is that we increase the ISR capability by re-raising D Company as a dedicated ISR company and renaming Support Company as manoeuvre support (MSpt) company. The MSpt company will consist of mortar platoon, direct fire support weapons platoon and command and signals platoon, all of which will assist the commander by supporting his ability to manoeuvre. These organisations would look much as they do now. The force structure of the ISR company, however, is expanded on below. It should be noted that under Infantry 2012 there is an increased manning liability within infantry battalions, and the raising of the ISR company would further increase this liability by a company headquarters staff and some extra snipers and intelligence analysts. It is suggested that this resulting manning bill is more than offset by the increased capability. The local population liaison cells (LPLCs), which are described below, are expected to come from outside the manning of an infantry battalion but would be attached to them as and when required.

D (ISR) Company

The role of the ISR company would be to conduct and coordinate ISR, analyse information gathered, interpret it and disseminate the results. The officer commanding would be in effect the battalion ISR officer working in battalion headquarters. This should not be mistaken as the old patrols master role. Rather they are responsible for coordinating a multi-layered approach to gaining information, and processing it in concert with the intelligence officer into intelligence that gives the manoeuvre commander, in this case the commanding officer, situational awareness on which to base decisions. The ISR company would be comprised of the following elements:

The Recon and Surveillance (R&S) Platoon. The R&S platoon would include, as it does now, both recon patrols and surveillance patrols. However, if the Army is serious about the concept of ‘recon pull’, and wants to maintain true operational tempo, then these assets need to be given mobility, and consequently increased reach and survivability. It is recommended that in light role battalions the R&S platoon is equipped with recon Landrovers equipped in the same manner as those which the RFSUs use now. The training and logistical bill for these simple vehicles would be small, and would be far outweighed by the tactical advantage offered by their employment. It is recommended that mechanised infantry battalions cease using the M113 for recon tasks and are equipped with ASLAVs. Before the Royal Australian Armoured Corps gets too excited we should remember that the ASLAV is not a cavalry vehicle, it is a capability platform. If it is good enough to be used by the Australian Army’s two reconnaissance regiments then it should be good enough to be used by the R&S platoons of the two mechanised infantry battalions. These would be crewed and commanded by recon-qualified Infantry soldiers.

Sniper Platoon. Snipers should be organised into a separate platoon both for training purposes, and also as they are an increasingly important force multiplier in their own right. Their utility has been proven in Iraq, Afghanistan and Timor Leste. It is suggested that they are commanded by a warrant officer class two.

Intelligence Platoon. Headed up by the battalions IO, the Intelligence platoon is critical to the ISR BOS, both for the direction of intelligence collation, and in interpreting the results. While the IO would still work in battalion HQ, the inclusion of the platoon in the ISR company would encourage better liaison between the elements responsible for the ‘know’ function. On deployment many of its specialists would be deployed to advise manoeuvre elements, such as rifle companies, on information gathering and perform initial analysis.

Local Population Liaison Cells (LPLC). In the future the Australian Army is increasingly likely to find itself conducting operations in countries with markedly different customs, cultures and language to our own. The ability to operate effectively in these foreign environments without alienating the local population could arguably mean the difference between operational success and mission failure. The role of the LPLCs therefore are twofold; firstly to plug into the local communities in which the manoeuvre elements are operating, and secondly to provide a trained CIMIC capability. These are two distinct functions and will be discussed in turn.

By introducing capability bricks into the Infantry battalion that have the language and cultural awareness to allow them to penetrate the local community, there is the ability to fix the enemy in time and space (i.e. to track them). Soldiers in the LPLCs should be both linguists and intelligence trained specialists, and accompany manoeuvre elements on patrols so as to maximise the amount of information elicited from the local population. This will be a significant capability increase for the Infantry battalion, but as a capability brick can be attached or detached as required for theatre-wide flexibility. The use of Field Human Intelligence Teams (FHTs), which is a similar but more specialised concept, by both British and US forces has led to notable successes in Iraq and Afghanistan. The introduction of LPLCs at the battalion level would be a recognition and response to this success right down to grassroots level.

Secondly, CIMIC projects are an important part of both separating the insurgent from his support and long-term planning for a post-insurgency future. As in any other area of soldiering, properly trained soldiers will deliver far better results than those who are given the task as ‘another hat to wear’. Soldiers working in CIMIC positions will deliver more focused, targeted projects, which in turn will have a greater consent-winning effect, if they are fully instructed in the culture and development needs of the country in question. In turn, the incorporation of LPLC s as an integrated part of the battalion will allow a much greater understanding of CIMIC issues by commanders and soldiers alike.

Logical Training and Deployment Cycles

Their training was so demanding, in fact, that the German Infantry were ultimately glad for the relief provided by war.

- Colonel A Goutard, 19406

The rapid fall of Poland and then France at the beginning of the Second World War was in no small part due to the inter-war training regime adopted by the German Army in the form of the Reichswehr and, after 1935, the Wehrmacht. Free of the modern shackles of occupational health and safety and corporate governance their officers devoted their time to training their soldiers in warfighting, especially offensive operations. The intensity of their training paid dividends when war broke out. It is worth remembering that the great mass of that army, which so crushed the Anglo-French forces in France in 1940, was the German infantry. Indeed the number of tanks at the Allies’ disposal outnumbered the fabled panzers, and it was the superiority of the German infantry, their understanding of the all-arms battle, and their sustained maintenance of a superior tempo which were the key factors in the German victory, rather than purely having a greater armoured capability.7 All this was incorporated in their knowledge, and practice of combined arms theory, much of which still guides our doctrine today. Fast forward to the twenty-first century, and, like the other allied armies, the Australian Army trains its soldiers to conduct high-intensity warfighting operations. This adheres to the philosophy that soldiers trained to such a level can operate across the whole spectrum of operations, while those only trained in, for example, peacekeeping will not be able to step up to conduct sustained high-intensity warfighting. This is a sound principle which has stood the test of time and worked well for the Germans.

However, just as important as training for warfighting is the manner in which that training is conducted. Training should be structured so that it is progressive, operationally focused and both physically and mentally demanding. It should begin with individual training, progress through small unit collective training up to company and battalion level, and then ultimately theatre specific pre-deployment training prior to units deploying. After pre-deployment leave the cycle starts again with individual training and so it progresses. This training cycle becomes more complex when both individual posting cycles and unit deployments need to be deconflicted, but it must be maintained in order for soldiers and units to be properly trained prior to deploying on operations.

At the time of writing the regular Infantry has approximately six subunits and two battalion headquarters deployed on operations in Iraq, Afghanistan and Timor Leste.8That is a total of less than two battalions. Yet the deployment cycle has become so complicated that in 2006, 3 RAR as Battlegroup Faithful in Timor Leste had under command a rifle company from each of 1 RAR, 2 RAR and 3 RAR. This is not battle grouping; it is organisational confusion. The fundamental principle which underpins training is that soldiers train together to prepare them for deployment on operations. This cannot happen if the Infantry are seen merely as a finite number of subunits to be thrown together at the next problem that raises itself. There is also the real danger that in the future the Australian Army could create an organisational fracture line if it continues to see its battalions and brigades as fulfilling merely the raise, train, sustain function, and who are ultimately simply required to fill slots in an operational manning document (OMD). The flip side of this coin is that the OMD is raised by staff in HQ Joint Operational Command, who in turn themselves have to be careful not to become divorced from the real-time training requirements needed by Land Command to develop and provide soldiers to be ready for deployment on operations.

It is no coincidence that the makeup of the present Infantry battalion includes its own integral combat service support (CSS) assets. These are designed to support the battalion on operations, so that when the battalion becomes the core nucleus of a battlegroup it remains at the heart an organisation which has lived and trained together. Developing a more capable Infantry battalion should not be seen as turning away from the concept of battlegrouping. Indeed it is quite the opposite. A more capable Infantry battalion ensures that on one hand the core base around which other parts are added is much stronger than before, and on the other has more inherent capability to offer other battlegroups based on armoured, cavalry or aviation regiments. Success, therefore, should be measured by how quickly it as an organisation can incorporate attached arms; how quickly they can combine their strengths to win in battle. By comparison, the current system of deploying forces, perceived by many at battalion level to be little more than an ad hoc solution, undermines unit cohesion, capability and efficiency. To that end, with programmed implementation of Infantry 2012 just over four years away, now would seem to be the ideal time to start planning, and where possible implementing, a logical training and deployment cycle.

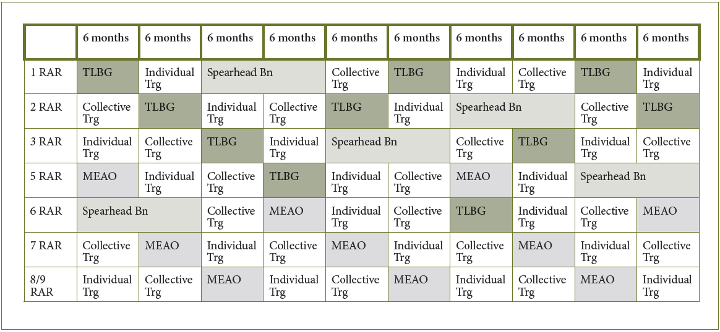

With the units available under the Enhanced Land Force, and with the operational commitments that the Infantry is presently undertaking, it should be possible to create a solid Formation Readiness Cycle (FRC) that allows structured progressive training, operational deployments, and an Infantry battalion to remain on high readiness as a spearhead battalion to deploy overseas on short notice. The spearhead battalion, as part of its continuation training during the year, could send three company groups on three month rotations to Rifle Company Butterworth (RCB) in Malaysia. This would see RCB being utilised as a versatile training opportunity, not as a deployment in its own right, and the airfield at RCB would allow short notice onward deployment of an acclimatised company group to any potential trouble spots within Australia’s area of strategic interest. It is suggested that the fourth rotation each year is taken by the Infantry Regimental Officers Basic course, which will train young Infantry officers in preparing for, and deploying on, operations. This would, however, require a significant change in thinking by the ADF on what RCB can or should provide the Army. It is suggested that now is as good a time as any for this challenge to institutional thinking to be laid down.

To further increase training efficiency, and with current troop deployments, Infantry could simplify its deployments by having a Middle East Area of Operations battalion commitment, a Timor Leste battalion commitment, and readiness battlegroup commitment. As current taskings stand, the MEAO battalion would be responsible for providing a battlegroup headquarters and two companies to Iraq (includes the SECDET task) and a company to Afghanistan. If Overwatch Battlegroup (West) winds up in the near future, as expected, then this will further relieve pressure and allow individuals to rotate from theatre to attend promotion courses and further trade training back in Australia.

The FRC can be linked to the postings cycle so that, for example, an officer commanding (OC) arrives at the beginning of the training phase, trains the company, and then deploys with them all within an eighteen month period. In a three-year posting to an Infantry battalion a major would therefore be in a position to complete two postings; once in a rifle company then as OC ISR, operations officer or executive officer. This system would also allow company commanders to spend more time commanding their companies, rather than the ten months or so that they get now, for as a Canadian officer who fought in Korea points out:

The success of Kapyong was due to mainly high morale, and to good company, platoon and section commanders ... that is something that we should never overlook in our military training. Too much officer training is aimed at high levels of command and not enough at the company and platoon level ... It is surprising how easy it is to command a battalion when you have had success in commanding a company.9

An example of a five-year FRC is shown below. Note that mechanised and motorised battalions are able to fulfil their core skill set and deploy as Light Role Infantry as and when required.

Figure 3. Five Year FRC

Conclusion

The Infantry needs to have the capability and confidence to undertake a more offensive role on operations. Although during recent deployments we have not been tasked to undertake the same offensive operational tasks as our sister units in the US, British and Canadian armies, when the question has been asked of the Australian Infantry, as it was during Reconstruction Task Force 3, we have not been found wanting. Hopefully this recent experience will allow the regular infantry to be considered for more aggressive roles in the future. To promote this concept this article has sought to highlight three ways in which the Infantry as a Corps can make the infantry battalion a more capable organisation for deployment on operations. The Infantry as a forward thinking, dynamic organisation needs to take up the mantle and ensure that it is as operationally flexible as possible to meet the challenges of the future. It can go a long way towards achieving this by embracing, and even enhancing, the changes due under Infantry 2012. The ISR company would greatly increase the Australian Infantry battalions ability to perform the ‘know’ combat function, which in turn shapes all other activities in both high-intensity and counterinsurgency warfare. This increase of capability would in itself make the regular Infantry battalion a far more attractive option to deploy on combat operations. Finally, if the Infantry can insist on a logical FRC that allows for individual and collective training prior to operational deployments, then its soldiers will be better prepared to meet and defeat the enemy in close combat. All this will combine to make the Infantry a more attractive option for the political and military hierarchy to commit to offensive operations.

Endnotes

1 John A English, On Infantry, Praeger Publishers, New York, 1985, p. 163.

2 Commonwealth of Australia (Australian Army), LWD 3-3-7 Employment of Infantry, Land Warfare Development Centre, Puckapunyal, 2005, p. 3A-1.

3 Centre for Army Lessons, The Infantry Mobility Vehicle [IMV] Aide-Memoire, Motorised Combat Wing, Centre for Army Lessons, Puckapunyal, 2006.

4 LWD 3-3-7 Employment of Infantry, 2005, p. 3A-1.

5 John A Nagl, Learning to Eat Soup With a Knife: Counterinsurgency Lessons from Malaya and Vietnam, Praeger Publishers, Westport, 2002, p. 73.

6 John A English, On Infantry, p. 80.

7 Ibid, p. 67.

8 Iraq: 1 x BG HQ and 1 x Coy OWBG, 1 x Coy (-) SECDET, Afghanistan: 1 x Coy, Timor Leste: 1 x BG HQ and 3 x Coys.

9 John A English, On Infantry, p. 218.