Abstract

The purpose of this article is to increase the level of understanding of operational analysis (OA) within the Australian Army, and in particular the utility of Tactical OA teams deployed in support of the tactical commander. Operational analysis is a decision support capability and is offered at most military universities in the Western world as a discipline of academic study at the postgraduate level. The article coins the phrase Tac OA and provides the author’s views on what comprises Tac OA, how it would be employed, and its utility for deployed tactical commanders.

Operations Research Systems Analysis is not business analysis, it’s warfighting capability analysis - a critical part of the Joint, Combined Arms Team.1

- General Benjamin Griffin, US Army

Former Commander 4th Infantry Division

Introduction

The Australian Defence Force (ADF) deployed its first Tactical Operational Analysis (Tac OA) Team in recent decades on operations in 2005.2 There has since been an effort to maintain a deployed Tac OA capability in the Middle East Area of Operations (MEAO) and some ‘on occasion’ presence in support of other operations. Most ADF tactical commanders have little exposure to a tactical operational analysis capability. The Australian Army’s understanding of operational analysis has been primarily confined to an emphasis on historical analysis and the identification and application of lessons derived from that analysis. Scientists at DSTO use operational analysis as a tool to support the capability development process. However, US, British and NATO forces have been employing tactical operational analysis for some time as a force multiplier for combat operations.

Modern operational analysis originated in the lead up to and conduct of the Second World War as a US and British innovation. Subsequently, operational analysis specialists supported British commanders during insurgency in Malaya, US commanders in Vietnam, as well as both US and British commanders during operations to liberate Kuwait in 1991. With the advent of computer-based wargaming simulations, operational analysis specialists employed these tools to support tactical planning for operations. In 1994, Major General William M. Steele’s 82nd Airborne Division invasion planning for Haiti used computer-based wargaming to refine tactical insertion plans. This approach enabled significant branches and sequels to be developed and analysed. Military operational analysis research is an academic discipline that has many applications; however, this article is solely focused on the Australian Army’s use of operational analysis to support deployed tactical commanders.

What is Tac OA?

Tactical operational analysis is a decision support capability for the tactical commander and their staff. Employment of a Tac OA Team enables a higher degree of analytical rigour in command decision-making. In an environment of uncertainty, Tac OA offers commanders greater confidence that their decisions have been informed by scientific analysis. Tac OA often provides counterintuitive results that in hindsight appear to be no more than simple logic or common sense. In many situations, there is a time lag between cause and effect that is not always immediately obvious. One of the more notable examples of successful, high-impact operational analysis (many have yet to be declassified) is that of convoy escorts for the British Merchant Navy during the Second World War. Merchant shipping transported troops and supplies for the war effort. German U-boats were sinking merchant shipping despite adaptive tactics and formations being used by the Royal Navy to provide safe escort. The Royal Navy could not increase the number of combat ships for convoy escort to overcome the U-boat threat.

The British Admiralty directed an operational analysis team to enhance the ongoing development of convoy escort tactics. The team initially defined their problem as determining the number of escort ships required to maximise the tonnage of merchant shipping reaching its destination safely. They then collected data on escort success rates in an attempt to find correlations with the various convoy escort tactics. The OA team worked out the U-boats were essentially getting a ‘kill’ regardless of both escort tactics and number of escort vessels. Generally, however, the Germans only achieved one kill because they were chased off by escort vessels after un-masking themselves while ‘making the kill’. Thus the operational analysis team proposed a solution that required the number of merchant vessels per convoy to be increased and the number of escort vessels to be decreased. Though this solution appeared to be counterintuitive, the operational analysis produced statistical evidence and the Royal Navy implemented the recommendations. The result was that a greater tonnage of merchant shipping arrived per convoy despite the provision of less escort ships. The analysis outcome was counterintuitive (less escorts, not more), but the logic proved to be undeniably simple.

A Formal Definition

In formal terminology, operational analysis uses scientific methods as well as a quantitative and qualitative rationale to improve situational awareness, to facilitate decision-making and to improve the quality and effectiveness of operational planning and execution. NATO uses the description ‘...OA provides quantitative analysis with a clear audit trail to inform the decision. OA does not just answer the question posed but seeks to identify ‘hidden’ concerns, branches and sequels.’3 Importantly, qualitative operational analysis provides analysis and models to assist in highlighting the critical problems for detailed quantitative analysis as well as solutions developed in-theatre or through reach-back as time permits.4

Operational analysis will be applied in a method appropriate to the task and the time available. However, a generalised OA method is provided as:

1. Problem Definition

2. Collect/Assemble Known Data

3. Model Problem with appropriate Qualitative or Quantitative Technique

4. Conduct Analysis and Develop a Solution Set to Problem

5. Communicate Analysis to Decision Maker

In summary, operational analysis is a systems approach to decision-making using analytical methods ranging from mathematical and statistical techniques (including modelling), through to soft operational research methodologies such as Influence Diagrams and Field Anomaly Relaxation.

Tac OA will often be seen as ‘rough’ by academic purists because it may lack the comprehensive scientific rigour of a technical study over a period of time based on complete data. However, a tactical commander requires timeliness of decision support rather than precision. An early trend is far more valuable than a delayed absolute answer. Tactical commanders will not have confidence in Tac OA unless decision support is delivered on time and in context.

The United States and United Kingdom continue to deploy operational analysis teams with their forces deployed in Iraq. An example-observed during the author’s deployment to Iraq in 2004—was the United States employing operational analysis to optimise timings for convoy movements to minimise the effectiveness of insurgent interdiction of Coalition road convoys.

In recent decades the Australian Army has generally employed operational analysis in the form of historical analysis to provide an archival record and to collect lessons in preparation of potential future deployments and operations. Australian tactical commanders will need to develop an understanding of how to employ Tac OA in order to leverage this combat force-multiplier capability on operations.

Why Deploy a Tac OA Capability?

The current threat force in Iraq has demonstrated a capacity to learn and adapt quickly with deadly effect. Threat force tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) have been continually modified to deal with Coalition TTPs and countermeasures. During his tour of duty in Iraq in 2004, the author observed that US divisional commanders believed the Iraqi insurgent cycle for changing their TTPs was in some cases between twenty-one and twenty-four days. Also, informal UK estimates of the rate of insurgent improvised explosive device (IED) development in Iraq put the figure at twenty times faster than that experienced in Northern Ireland.

The Australian Defence Force needs to use all means available to increase the survivability of our troops, enhance their effectiveness, and reduce the risk of casualties. Tactical-level operational analysis capabilities can assist commanders and their force elements to adapt in a complex and changing threat environment faster than the threat.

There are a range of advantages in addition to decision support. These include:

- Expertise and staff capacity available to the commander for developing in-theatre user requirements for rapid acquisition and support to spiral development for emergent capability requirements;

- A link for the commander and staff to leverage in-theatre coalition Operational Analysis capability and products; and

- A conduit for a commander to reach back for timely deeper level analytical, simulation, experimentation and other scientific support in the National Support Area.

Employing Tac OA

In simple terms, commanders should employ Tac OA in whatever form that enables the Tac OA Team to support their decision-making. Commanders will have their own individual decision-making style. In most decision situations, a commander will not require Tac OA. However, Tac OA will have greatest utility in those situations where it is essential to learn and adapt quickly to new or changing circumstances. Typically, these circumstances will be unfamiliar to commanders and their force elements and be accompanied by higher levels of uncertainty.

Tac OA does not replace a commander’s professional military judgement. Commanders will always be accountable for their actions and responsible for final decisions. Tactical commanders are often faced with making decisions with low levels of certainty in situational information. Tac OA, when employed and executed appropriately, should enhance the level of confidence of commanders in the decisions they have made.

Prior to D-Day for the First Gulf War, Major General Rupert Smith, Commander 1st UK Armoured Division, tasked his Tac OA Team to work out how much of the opposing Iraqi combat force could be engaged before having to stop the Division and reconstitute combat power. This problem was defined as what was the Iraqi force ‘bite-size chunk’ capability of the UK Division. This historical Tac OA task has since become known as the ‘Bite-Size Chunk Problem’. Major General Smith did not accept the Tac OA results and he used a far more conservative estimate—a very defendable professional military judgement. Coalition forces moved quickly through the Iraqi defences on D-Day and Major General Smith increased his bite-size chunk up to that estimated by his Tac OA Team. Arguably, Major General Smith had an increased level of confidence to rapidly increase his bite-size chunk based on Tac OA.

Currently there exists no ADF doctrine to guide tactical commanders on how to employ Tactical OA. However, there are a number of guiding principles for a tactical commander to consider.

- Situational Awareness Reduces Response Time: Fast analysis to support shortnotice decision-making requires current situational awareness.

- Context is Critical: Decision context is critical to quick and effective problem definition.

- Agree Problem Definition: If time permits, define the problem for analysis and the decision to be made.

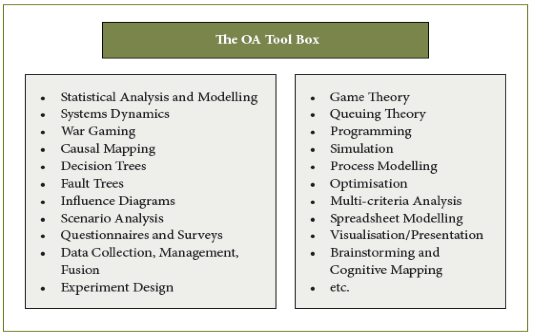

- The OA Tool Box: An operational analyst will have had training in an extensive array of OA techniques (see Figure 1). Commanders should look for opportunities to exploit these techniques in support of their decision-making.

- Tac OA Does Not Replace a Commander’s Professional Judgement: The Commander should treat Tac OA results the same as advice from any other technical/specialist adviser. Commanders may choose to accept or not accept technical/specialist advice in their decision-making based on professional judgement.

- Practice Tac OA Team working with Commander and Staff: Mission rehearsal exercises (MREs), command post exercises (CPXs), tactical exercises without troops (TEWTs), joint military appreciation process exercises (JMAP EX) and other training opportunities should be used wherever possible for members of Tac OA Teams. This constant practice develops relationships with commanders and their staff to better understand their unique decision-making processes. Such activities enable Tac OA Teams to develop operational analysis decision support methods that best compliment the commander’s decision-making process and supporting staff procedures.

Examples of Tac OA recently provided to US commanders in Afghanistan and Iraq include:

Recommend changes in the emplacement of counterfire radars to maximise effectiveness in identifying mortars and rockets aimed at base camps.

- Examine the locations of IEDs to determine possible enemy cache locations.

- Assess counter-IED procedures to reduce attacks on convoy supply routes.

- Develop metrics and assess plans and operations to adjust future operations.

- Analyse critical nodes and desired effects in the Joint Effects Working Group to modify operational plans.

- Analyse poll results about counterinsurgency operations to gauge the success of efforts to win the hearts and minds of the local population.

- Examine militia re-integration as a way to begin disarming private armies.

- Assess the effectiveness of combat and security operations on enemy activity.

Figure 1.

The Way Ahead

Tac OA teams need to include scientists and uniformed operational analysis practitioners who clearly understand the warfighting aspects of the commander’s planning and decision-making. The ADF needs to develop this capability with increased numbers of OA-trained uniformed personnel, preferably PSC (Passed Staff College)-level officers, and by writing the supporting doctrine.5

The US Army has specific staff streams known as Functional Areas and operational analysis is designated Functional Area 49 (FA49). US Army Operations Research Systems Analysts (ORSA) personnel can expect postings into their Functional Area when not employed in their primary Branch (corps). FA49 personnel receive operational analysis training that varies from a three-month short OA course through to a two-year postgraduate Masters degree. Prior to deployment in a FA49 position, they attend an eight-day predeployment OA course. FA49 personnel are employed within US warfighting headquarters in two- and three-person OA teams that are part of the deployed headquarters structure. NATO teams are larger and more self-sufficient.

The US Army model for managing their operational analysis capability outlined in the previous paragraph highlights the value that the US Army places on a deployed operational analysis capability. The Australian Army may not have the resources to mirror the US model, yet work is required to ensure the Australian Army has a method of developing and maintaining an appropriate operational analysis capability for use on exercises and operational deployments.

As the ADF’s concept of network-centric warfare matures there will be a move from a desire to achieve information dominance to achieving knowledge dominance, before finally focusing on the key NCW outcome of decision dominance. While a networked force is a key capability enabler for decision dominance, Tac OA is the capability a tactical commander can employ to leverage the benefits of NCW to achieve decisive decision dominance.

Conclusion

Tac OA as described in this article is a capability previously untested on operations in recent time by the ADF prior to 2005. With the current deployment of a Tac OA Team in support of current operations, the capability is expected to develop in both applicability and effectiveness. Commanders and staff will mature their understanding of how to employ Tac OA in order to learn and adapt quickly in a complex environment, thus enhancing deployed tactical decision-making.

Enhancing learning and decision cycles on operations are critical if Australian Army force elements are to adapt their techniques, tactics and procedures faster than opposing threat forces. Tac OA in general—and employment of embedded Tac OA Teams in particular—is enhancing US and UK operations in complex terrain against a learning enemy. The Australian Army will need to apply resources in order to catch up with our allies.

Endnotes

1 Quoted in Lieutenant General David F. Melcher (US Army) and Lieutenant Colonel John G. Ferrari (US Army), ‘A View from the FA49 Foxhole: Operational Research and Systems Analysis’, Military Review, Vol. LXXXIV, No. 6, November-December 2004, p. 2.

2 Scientific Support Teams have been previously deployed on ADF operations; however, 2005 saw the first deployment of an OA Team with both a scientist and a Masters-qualified operational analysis military officer.

3 NATO, Research and Technology Organisation, NATO Code of Best Practice on Decision Support for CJTF and Component Commanders, AC/323 (SAS-044)TP/46.

4 Reach-back is a concept whereby capabilities based in the National Support Area are accessed by the deployed force using an appropriate means of communication.

5 Army has trained one OA officer every two years since 1990. Only one of these officers is currently still serving.