Abstract

This paper makes explicit a process for developing moral leadership and ethical decisionmaking. It provides insight into the theoretical frameworks and practical outcomes that have been inserted into the All Corps Soldier Training Continuum promotional courses and provides a series of recommendations for further effort.

Introduction

In a world of far-flung deployments, uncertain and fluid environments and persistent media coverage, the strategic soldier makes snap decisions every day that may have profound consequences. Each individual soldier’s character impacts significantly upon their ability to provide effective leadership across such a range of situations. The All Corps Soldier Training Continuum (ACSTC) focuses on common training and the leadership development of the Australian soldier. In modern warfare, and its associated ambiguities, an important element of leadership development is the formation of character, which has always been seen as important for the Australian soldier. It is for this reason that character development is embedded within the ACSTC.

In 2005 and 2006, Land Warfare Centre (LWC) Chaplains began a re-development of the ACSTC moral leadership components, culminating in the construction of a moral leadership package, to be inserted across the ACSTC corporal to regimental sergeant major (RSM) subject one promotional courses. This development involved an informal training needs analysis, engaging ranks from corporal to RSM in Sydney and Brisbane, and input from Promotions Wing at LWC, Canungra. Additionally, a review was conducted on current doctrine, training packages and policy guidelines dealing with leadership and the ideal character for the modern Army environment.1

Character Doctrine Within the ADF

In reviewing the current state of character training across the ACSTC, beginning from entry-level training through to the Officer Grade 2 course, it was found that much of the material failed to engage doctrine, and that doctrine itself failed to provide enough substantive frameworks from which the development of character training could emerge. There are inconsistencies and lack of correlation between the various training points along the ACSTC spectrum to support an overarching development of character. While some good material existed, it was found that much of character training existed adjunct to doctrine, and failed to provide an adequate continuum upon which leadership and character could be developed. In addition, much of it failed to engage a whole-of-training approach, seeing character as an additional training point, rather than part of both doctrine and current Army policy.

Land Warfare Doctrine 0-2-2 Character2 was released in 2005. Both LWD 0-2-2 Character and LWD 0-2 Leadership3 overlap on numerous points, indicating they should be read within the context of the other. Character tends to brush over various points regarding character without providing much substance. It relies on anecdotal material, promotes a somewhat mythological ideal of the Australian soldier, and fails to give adequate theoretical frameworks for some of its key concepts. In addition, its release should have prompted a total review of current character training to ensure that it supported doctrine. This has not occurred outside the development of the moral leadership package within LWC.

Observations on Character Doctrine

As a result of the review and the information gathered, several observations emerged. The first focused on Army ethos and values, which were generally viewed negatively by those engaged, even though they upheld a perspective that affirmed their importance. Significantly, many commented that rarely were the ethos and values displayed by those who imposed them, and that the social make-up of those entering the Army did not lean towards adopting such values as their own. The second observation engaged the position of RSM, who was seen as the most significant figure in which all elements of being a soldier should be found. Many, including RSMs, indicated that while they believed this to be so, reality indicated differently as the subjugation of Army bureaucracy overwhelmed the position with superfluous tasks. The third observation focused on ethical decisionmaking, which was perceived as a declining skill amongst many in the Army. Most felt that this affected all of Army, and all within the chain of command have a responsibility for both modelling and mentoring this skill. Fourthly, beliefs and world views emerged as a focal point in which it was found that most respondents could not adequately articulate a belief system, much less identify the world view that governed much of Army’s understanding of character.

The significant outcome was that a framework for developing a world view was needed. This framework needed to be articulated within the various transitional levels of promotion, and out of it both an understanding of what shapes character and how an individual’s character affects ethical decision making needed to be developed.

A Conceptual Framework for Moral Leadership

Character formation within the ACSTC promotional courses needs to address two distinct areas. First, the individual needs to have the skills to articulate a world view appropriate to her or his rank level, and understand the implications of that on life as a soldier and potential leader within the Army. Second, the individual needs to be able to function ethically as a leader, particularly in the ability to make morally sound decisions across the range of environments that may be encountered. An individual’s world view and the ability to think ethically need to be an integral part of the soldier’s self-identity. This self-identification enables the individual to act morally and ethically in an instinctive manner to any given scenario in any military context.

A Model for a World View

While numerous models of world views exist, many are either tainted by a particular cultural, religious, theological, or sociological perspective, or are too complex to sustain in a multicultural and multi-religious environment such as Army. The model developed by Frederick Streng4 provided the capability of translation into a military context, in which the diversity of views within this environment could find a common framework. All models have their flaws, and Streng’s is no exception, nevertheless his model is most useful in defining a structural approach to a world view.

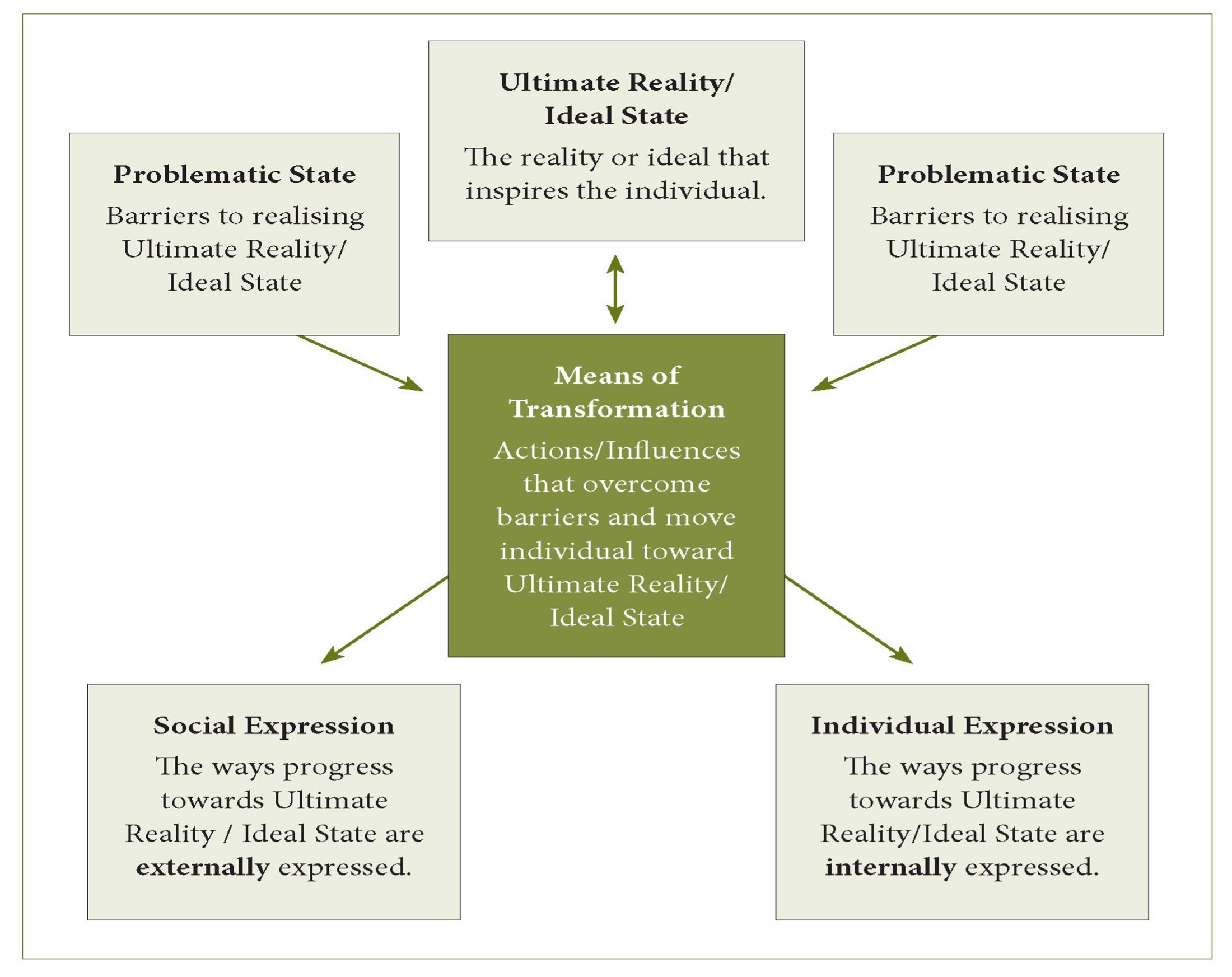

Streng’s model contains five elements. The first is the ultimate reality that is understood as the ideal to which an individual is intimately linked and by which all aspirations in life are shaped. The second is the problematic state, which contains the barriers that prevent the ultimate reality from being fully realised. The process of change is the third element, and is understood as the means of transformation. This transformation overcomes the problematic state and permits the individual to achieve intimacy with the ultimate reality. The outcomes of the transformation are realised by the last two elements. The first of these is individual expression, which comprises the internalised changes evident in the individual in terms of self-awareness. The second is social expression, the externalised actions that provide evidence of the individual’s shift toward the ultimate reality in terms of social interaction. This is seen by Diagram 1.

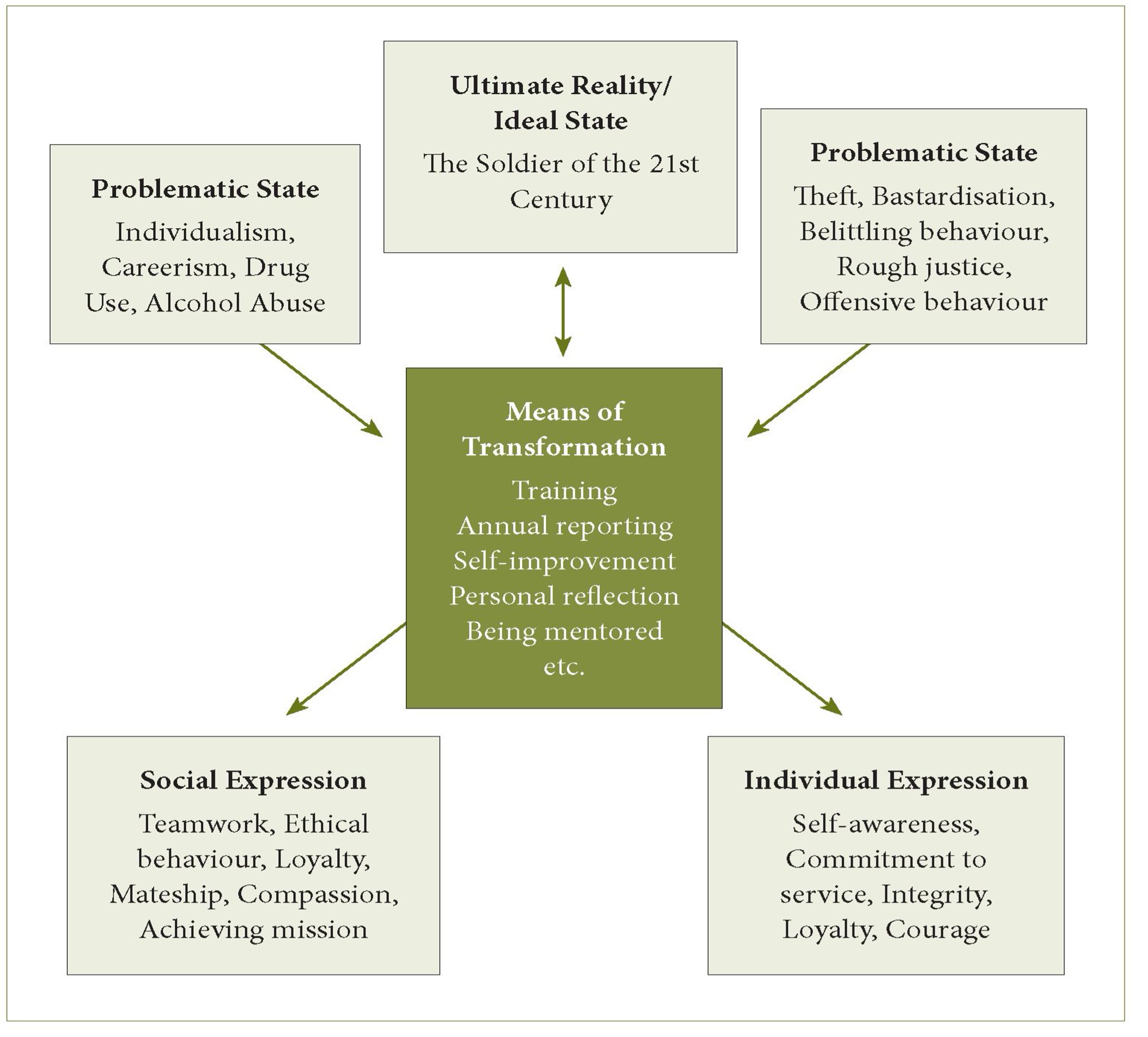

This model can be translated into an Army framework using the concept of the ‘Soldier of the 21st Century’.5 This concept contains nine traits integral to being an Australian soldier:

• Every soldier is an expert in close combat.

• Every soldier is a leader.

• Every soldier is physically tough.

• Every soldier is mentally prepared.

• Every soldier is committed to continuous learning.

• Every soldier is courageous.

• Every soldier takes the initiative.

• Every soldier works for the team.

• Every soldier demonstrates compassion.6

This concept identifies a standard to which all are expected to self-develop. The reality is that no-one can embody them perfectly and, therefore, the model identifies both the ideal and the problematic. The soldier strives to self-realise the ideal, but also needs to overcome barriers that prevent such self-realisation. The process of undertaking this effort requires transformation in the individual. Such transformation aids in shaping self-identification as a soldier, and presents an external image that others identify with the concept of being an Australian soldier. This is seen in Diagram 2.

Diagram 1. Streng’s Model of a World View.7

Streng’s model enables individuals to grasp a comprehensible world view in a structured format into which Army doctrine and intent can be inserted. It is robust enough for individual adaptation without compromise of fundamental belief systems, yet permits the merging of Army’s ideal soldier into the overarching world view of the individual. A training model can be developed in which individuals can be empowered to facilitate their own personal transformation processes.

One of the pragmatic issues that arises is ‘how does this transformation manifest itself?’ Another issue is: against what visible standard should the ideal be measured? Based on the research undertaken, it was concluded that the position of RSM embodies the totality of the ideal soldier, and as such the nine elements of the

Diagram 2. Streng’s model applied to Australian Army.

‘Soldier of the 21st Century’ should be embodied by the RSM. The diversity of personalities, style, trade, corps, beliefs, etc., all enable Army to have a variety of expressions of the ideal. It is for this reason that the individual best qualified, by status, experience, knowledge, development and learning, to impart the concept of the ‘Soldier of the 21st Century’ to soldiers is the RSM. It is not the role of the Chaplain to impart these concepts to soldiers; the Army Chaplain has an integral role of conceptualising these values for individuals based on the lived example of the RSM. As such, the RSM and Chaplain must work as a team in placing before soldiers the ideal, the problematic required to be overcome, the means of transformation and the forms of expression such a relationship with the ideal delivers to both the individual and all within the Army organisation. The RSM needs to both state and embody the ideal to subordinates, while the Chaplain needs to assist individuals to comprehend why the ideal is so important to character formation. This has a training implication in the delivery of character formation.

A Model for Ethical and Moral Thinking

The process for ethical decision-making grows out of a world view. The ‘individual’ and ‘social expression’ is the nexus where ethical and moral thinking manifest into action. However, the model for making ethical and moral decisions also needs to fit into the model of decision-making within the Army. LWD 0-2 Leadership identifies a rational process of decision-making:

Step 1 - Define the problem.

Step 2 - Identify the object of the decision.

Step 3 - Analyse the situation.

Step 4 - Identify and assess the alternatives.

Step 5 - Decide the best course of action.

Step 6 - Implement the plan and evaluate the results.8

An ethical decision-making model was adapted from the work of the Markkula Centre for Applied Ethics9 that met the generic criteria needed for use within the Army context. This framework is:

- Recognise an ethical issue

- Get the facts

- Evaluate alternative actions from various ethical perspectives as follows:

- Utilitarian Approach—the greatest benefits over harms

- Rights Approach—most dutifully respects the rights of all

- Fairness or Justice Approach—people are treated equally, proportionally, and fairly

- Common Good Approach—contributes most to the achievement of a quality common life together, and

- Virtue Approach—embodies the habits and values of humans at their best.

- Make a decision and test it:

- Which option is the right or best thing to do?

- If you told someone you respect what would that person say?

- Act then, reflect on the decision later. (How did it turn out? Would you do anything differently if the same situation occurred again?)

In adapting the above for use within Army, some modifications are required. For example, the Virtue Approach, and talking over the decision with a trusted individual, is translated into the concept of Transparency and is an easier concept for soldiers to grasp while still reflecting the essence of those approaches. Testing a decision is dropped from the model, and replaced with ‘determine the best action, take the action, and reflect upon outcomes’, which accurately reflects the rational military decision-making model found in LWD 0-2. Additionally, two further dimensions need to be added. These are the lawfulness of action10 and consistency with the commander’s intent.11 These are included because they embrace the environment in which Army functions. Warfighting, in the Australian context, includes clearly defined parameters set within a legal boundary. All ethical decisions must take into account lawfulness of action and commander’s intent if they are deemed valid, and as such the tests used should affirm or confirm the validity of the proposed action. The endpoint for moral leadership and the ethical thinking model is that the soldier is able to do the right thing at all times. The model for use within Army then looks like the following.

- Identify the facts

- Identify possible actions

- Test against:

- Greatest balance of benefit versus harm

- Respect full rights and dignity of all

- Fair and just outcomes

- Contribution to the common good

- Action consistent with individual world view

- Transparency

- Lawfulness of action (i.e. compliance with legal regulations, laws of armed conflict, rules of engagement, etc.)

- Consistency with commander’s intent or mission imperatives

- Determine the best action

- Take action best suited for situation, and

- Reflect upon the outcomes of the action.

The variety of ethical models employed in the model provides choice. Not all apply to all situations. The use of such diversity provides individuals with a variety of tools within the one framework from which to function effectively in an everchanging complex environment. Furthermore, it relies heavily upon the concept of the ‘Soldier of the 21st Century’ being the basic world view that is embedded within the solider. This model provides a holistic approach, using the developing ‘virtues’ within the soldier as the point from which all decision-making is based.

Conclusion

The research undertaken was a challenging and adaptive re-evaluation of how Army currently delivers character training and what shape that should take within the ACSTC. From this several recommendations were made. They included:

- The adoption of Streng’s model of a world view, using the concept of the ‘Soldier of the 21st Century’, to enhance and clarify the intent of doctrine and the delivery of those elements seen as crucial within doctrine for the leadership development of the Australian soldier.

- The adoption of the Markkula Centre for Applied Ethics model for ethical thinking, as adapted by this paper, within the leadership decision-making process of the promotional courses of the ACSTC as a tool that enhances Army’s current decision-making processes and enables soldiers at all levels to not just act morally but to make decisions that are morally and ethically sound.

- That a review of all courses within the ACSTC take place in light of the new LWD 0-2-2 Character and changes be made that embrace Streng’s model of a world view and the adaptation of the Markkula Centre for Applied Ethics model for ethical thinking to ensure a more robust and sustainable outcome is achieved.

- That a review of character training across Army be undertaken to ensure that units are resourced with the skills and methods needed to ensure that character development remains an ongoing concern for all elements within Army. In particular, this review should explore ways by which the ‘Soldier of the 21st century’, as expressed using Streng’s world view model, can be applied at local unit level, and soldiers can be practiced in ethical decision-making using the adaptation of the Markkula Centre for Applied Ethics process.

The research and development of moral leadership within the Army sought to clarify what was required for the moral leadership elements of the ACSTC. This simple project identified a deficiency, across all ranks, which demonstrated soldiers were unable to articulate a clear understanding of who they were as members of the Australian Army and their place as soldiers in the world in which they live. Similarly, the research highlighted an inability to fully embrace and retain such an understanding even if it had been or was presented to them. It was further identified that this group generally lacked the tools required for articulating a process for ethical and moral thinking. To ensure consistency across Army in the delivery of character training, specifically moral leadership within the ACSTC, this paper has argued that the same framework for understanding Army values and ethos within a world view and a means to think ethically needs to be taught in the ACSTC promotional courses. Finally, it has raised the issue of the development of character across Army and has offered a possible framework in which it may be developed in the future.

Endnotes

1 The results of this research are found in Major David Grulke The Development of Moral Leadership for the All Corps Soldier Training Continuum, Land Warfare Studies Centre Working Paper 133, Land Warfare Studies Centre, Canberra, forthcoming 2008.

2 Commonwealth of Australia (Australian Army), Land Warfare Doctrine LWD 0-2-2 Character, Land Warfare Development Centre, Puckapunyal, 2005.

3 Commonwealth of Australia (Australian Army), Land Warfare Doctrine LWD 0-2 Leadership, Land Warfare Development Centre, Puckapunyal, 2002.

4 Frederick J. Streng, Understanding Religious Life, 3rd edn, The Religious Life of Man Series, Wadsworth Publishing Company, Belmont, 1985.

5 This has since been re-released as I am an Australian Soldier cf. Australian Army CA Directive 16/06, 19 Oct 2006. Commonwealth of Australia, ‘I’m an Australian Soldier (developing the soldier for the HNA)’, Department of Defence, 2006.

6 Ibid, 1-6 - 1-7.

7 Streng, Understanding Religious Life, pp. 4, 23-24

8 Commonwealth of Australia, LWD0-2 Leadership, 12-5.

9 Velasquez, Manuel et al, ‘A Framework for Thinking Ethically’, The Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University. accessed on 7 September 2007, <http://www.scu.edu/ethics/practicing/decision/framework.html>.

10 Lawfulness of action incorporates the rules of engagement, the laws of armed conflict, etc. These are assumed within the model to be ethically sound and are therefore unquestionable criteria against which all ethical action must be measured.

11 Commander’s intent also assumes that the commanders intent is consistent with the laws of armed conflict, the rules of engagement, and as such is ethically sound.