Abstract

A need for a cultural shift in the application of Australian air power is gaining wide acceptance. Reach and precision were seen as the key enablers for the application of future air power—an attempt to re-focus on more than the air-to-air approach that has guided air power theory for numerous decades. Without actually recognising it, these concepts are starting to parallel land manoeuvre theory. The drive for reach and precision at the strategic level will offer great benefit to the application of tactical air power. Only by combining this with synchronised land manoeuvre, and a greater tailoring of air power capabilities, will we actually achieve the effects desired by the new air power theorists.

Sometimes we feel we are so busy stamping ants, we let the elephants come thundering over us.1

- Officer in United States Air Force, Directorate of Doctrine, 1974

Introduction

We seem to be living in an age where military changes are occurring at an unprecedented rate. Whether this is a product of a greater level of access to the thoughts of others or the continuing rise of technology itself as a major societal driver is unclear. We have had jargon and fad terms—’waves’, ‘RMAs’, ‘nets’, and ‘effects’—thrown at us with startling frequency over the last decade. The enemy has also changed; they are now ‘asymmetric’ and continuously seeking ‘weapons of mass destruction’ to achieve their ends. This paper considers the promise of air power and discusses how it can be best utilised against an enemy that is, for all Western militaries, non-traditional in nature.

Determining what really has changed in the military realm will be the task of historians in 20 years time. Attacks similar to those that occurred in the United States on 11 September 2001 were written about in novels well before becoming a reality,2 as has US engagement in the Arab oil region. Yet now these fictional events have become realities that affect the conduct of the Western way of war. Further, in the United States at least, the inter-service doctrine arguments continue and are probably serving to cloud the fundamental changes that are needed in the application of both land and air power.3 The current war in Iraq may be forcing convergence or, at the very least, stalling divergence; however, that war will end and, as history has shown, peace is not a unifying force for fiscally constrained Services.

The astute observer, studying the Israel/ Palestine conflict or the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, would not be surprised at the events unfolding in Iraq. Richard Simpkin, noted military theorist, provided the simplest analogy, even if his focus is primarily with regard to conventional warfare. While espousing the eventual transition of NATO-based conventional forces to a way of war where ‘special type’ forces have a potentially decisive effect, Simpkin states that, in the future, ‘my defensive use of gallant special forces in the cause of freedom is “your” subversionary activism in violation of international law and “his” government sponsored terrorism’.4 This means that perspective and context are critical, non-material factors in warfighting. Simpkin’s analogy defines the adversary at the heart of the Army’s Complex Warfighting paradigm.5

This is not to infer that jihadists are at the level of skill or training of high-end special forces, but the minimum-mass tactics that they adopt do bear some correlation. This ‘new’ enemy aims to achieve strategic ripples from minor tactical action. Thus, we are now faced with a belligerent of lesser total combat power than a NATO/ US/UN opponent—willing to wage war in complex terrain with a high level of non-combatants. Even if the enemy fails to achieve success at the outset, they will still fight and continue to do so for a long time, regardless of the real or perceived progress made in defeating them. This contradicts one of air power theory’s more grandiose claims: ‘We are moving on into a time, where if we know where the target is and we have basic characteristics of the target, we will be able to destroy that target anywhere on the planet’.6

Air Power

Two of the cornerstones of air power in the Australian context are ‘reach’ and ‘precision’—enabled by high technology.7 As such technology develops, offering new hope of success on the battlefield, can we fully use and control it? Or is high-technology air power merely the increasingly precise and aware application of high explosive? How can the grand theories of ‘strategic strike’ apply to an enemy that is difficult for an infantryman to detect on the ground, an enemy that understands the importance of remaining below the ‘detection threshold’ of their conventional, nation-state opponent?

Already the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) has recognised that cultural change is needed. The current Chief of the Defence Force, quoted from when he served as Chief of the Air Force (CAF), said: ‘air superiority will not necessarily be won by air combat’.8 Reach and precision are the tools of the new air power proponents, and have given older platforms (such as the B-52) a new lease of life.9 Control of the air is the primary driver for the RAAF and other roles become ancillary, albeit important.10 Thus, the RAAF contributes ‘reach and precision’, whatever the warfighting context. Whilst that is promising, is it enough and where should it be deployed? More importantly, in the counterinsurgency fight, is this new-found utility increasing the role of air power, or has it pushed it to the edge of conflict?

Australian forces have been defeated even with total air superiority—as in the Vietnam War. They have also conducted operations where the risk of direct military confrontation was low—as in East Timor. Let us assume that air combat assets are now able to turn their efforts to land-focused operations. Let us also assume that maritime surface and sub-surface issues are also relatively settled.11 How then do we effectively apply air power in a complex warfighting environment?

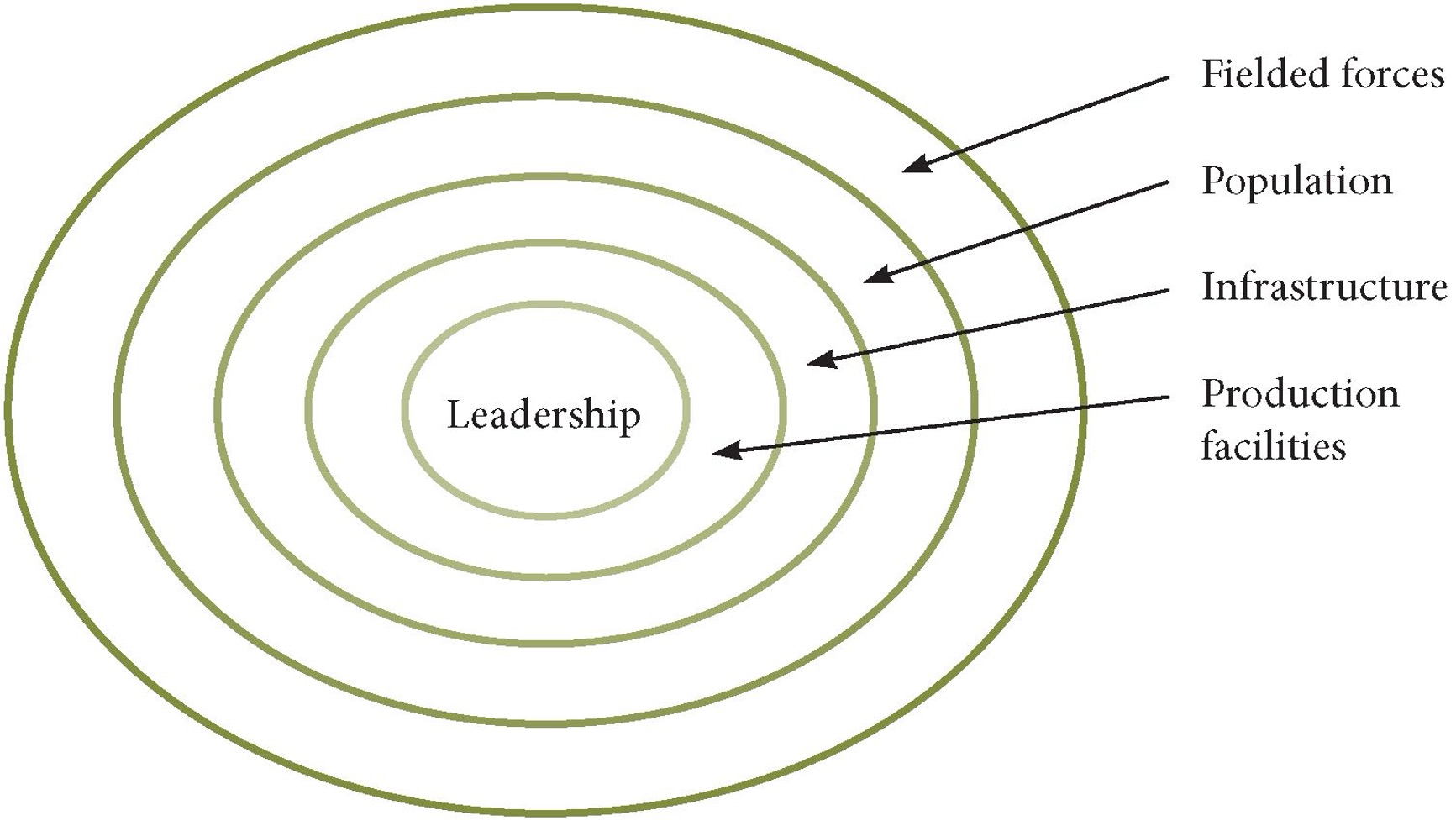

The default thinking for air-power planners would be to shift to a working of Warden’s rings—’a methodology for successfully attacking and paralyzing a conventional enemy system in depth’12—and a strategic strike targeting-cycle.13 Here, reach and precision could theoretically achieve the effect required at the strategic level.

Even against the nation-state, this has been contentious (the claims of air power advocates about Kosovo notwithstanding).14 Numerous exceptions exist, with the Vietnam War being the most notable—and often cited failure—of air power’s war-winning ability. Whether, in the case of Vietnam, this was due to misapplication is irrelevant; the outcome is what matters.

Figure 1: Warden’s Rings

Coercion and Deterrence

It is arguable that all forms of warfare—and air power in particular—work by coercive force. Future war, with a pervasive and subtly controlled media, will only promote coercive force into greater prominence; constituencies on all sides can be influenced quickly. Despite the argument regarding the decline of the importance of the nation–state in the conduct of conflict, coercion is still likely to remain the ultimate effect of the application of air power. We should not ignore the other side of the coercion coin—deterrence. However, in the Australian military context, we can only deter those threats that are considered slight in terms of national or regional threat. Coercion theory is the stuff of conflict; deterrence the stuff of avoidance.

Richard Pape contends that military coercion attempts to achieve political goals ‘on the cheap’.15 He wrote this in the context of the application of air power to coercion theory. His contention of fighting ‘on the cheap’ accords with land-based manoeuvre theory such as that espoused by Robert Leonhard, Richard Simpkin and others. New theorists aside, no rational military planner would seek to achieve victory other than by the most inexpensive means possible in terms of life and resources. In an analysis of the will of various high commands during modern war, Pape states that the ‘will’ of the commander is not fundamentally affected (it shifts yet remains unchallenged) until either the capability of his land forces to defend the homeland or the sovereign territory itself is under severe threat: ‘When coercion does work, it is by denying the opponent the ability to achieve his goals on the battlefield’.16

So, in the context of past battles, coercion could not be fully leveraged until a direct and persistent threat was placed against the core of a nation (i.e. invasion or destruction). ‘Manoeuvre Theory’ would ascribe this to a case of directly threatening the centre of gravity. We must take the same approach with a low-signature enemy. Coercion attempts to change an adversary’s behaviour by manipulating cost and benefits.17 The most oft-cited example of the application of air power is the war in Kosovo. Regardless of the effectiveness that will finally be ascribed by history to air power, Slobodan Milosevic was placed in a position (probably when Russia withdrew its support) where the cost of maintaining military power in Kosovo was outweighed by the loss of his political power base in Serbia.18 In simple terms, coercion is more likely to succeed ‘when the coercer can increase the level of costs it imposes, while denying the adversary opportunity to neutralise those costs or counter escalate’.19

Air power, with its reach and precision, has been deemed a natural choice for coercive efforts. However, the predominating view in planning such operations is to treat the enemy as a system (i.e. Warden’s rings) and this tends to underestimate an enemy’s ability to adapt—to change the system.20 If the enemy can adapt, then a coercion strategy must be used to place them on the horns of a dilemma. We must lock-in their decision cycle, not just think faster than them. This will not be achieved by simply dropping an ever-increasing amount of high explosive on the enemy, regardless of reach and precision. Such a move will, at best, only force an adversary to change posture. One uniformly conceded point with respect to Kosovo is that the campaign did not stop the Serbian Army from committing its ‘ethnic cleansing’ of the Albanian Kosovars. This only ceased following the withdrawal of the Serbian Army; air power prevented the Serbian Army from practising conventional, but not unconventional, operations.

Strike

Yet, who and where are the targets within a dispersed state or non-state adversary in a strategic air campaign? A sustained strike campaign in its traditional form is already somewhat contentious. Reach and precision are of little use if you only have two targets. Yes, the training camp was taken out, but what then? Thus, in the case of the new enemy, we should assume, not in a dismissive manner, that if a strike is possible, it will be carried out. However, it is not a sustained effect.21 The ‘shock and awe’ will, at best, stun rather than break the jihadists and their ilk. They can be shocked, but they will recover because they have time and a homeland (their ideology) that can neither be threatened by high explosive nor physical occupation.

The four broad targets of strike—will, national wealth, human loss, and military power22—become less tangible against the non-state actor. Pape has also identified that those coercion campaigns which use air strike focused on ‘denial’ as opposed to ‘punishment’ appeared to be the most successful. Both Gulf Wars proved that, in the right terrain, conventional forces are vulnerable to strategicor operational-level ‘deny/disrupt’ operations.23 Guerrilla campaigns, unfortunately, are far less susceptible. The guerrilla (in core concept) is not heavily reliant on air power in any form and is able to lower his detection threshold by ‘disappearing’ amongst the people. Indeed, do reach and precision even matter? The concept of a traditional air-denial operation is lost against the non-state actor.

Without going into a deep analysis of the relative merits of strategic strike, we have a troubled doctrine against an enemy with a low strategic detection threshold. Yet air power hurts an enemy when detected in a way that no land system can. How do we develop a synergy to maximise air power’s potential? Royal Australian Air Force doctrine accepts that we fight in a joint domain, thus there exist two other forms of offensive support to the land battle: interdiction and close air support. The requirements driving the improvement in the performance of conventional strategic strike platforms and weapons will offer benefits at the tactical and operational level, both in effect and effectiveness. It is here that precision and reach may come to the fore—with some important qualifications.

Introduction

As far as air interdiction is concerned, there are a number of factors that contribute to success. Mutually supported ground and air operations are recurring enablers of that success.24 Generally, the force with the initiative is able to lever interdiction, but exceptions do exist (as in the early stages of the Korean War, where UN forces were able to conduct interdiction operations whilst on the defensive).25

For the future enemy in complex terrain, simultaneous air/ground operations will be essential for successful interdiction. The contentious model of using proxy forces—such as the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) in Kosovo26—is neither a validated nor an ADF doctrinally accepted concept. However, any interdiction operation against a low-signature enemy requires synchronisation. Moreover, the strategic driver of reach and precision, synchronisation, becomes essential for successful interdiction. Intelligence capability will also be a primary enabler and again it is likely in future war that human or signals intelligence (HUMINT/SIGINT), as opposed to image or electronic intelligence (IMINT/ELINT)-type capabilities, will be a key factor. It is also likely that, in the future, interdiction will require a far greater level of responsiveness. Reach and precision will not be enough. We are seeing this trend emerging already with the so-called ‘Time Sensitive Targeting’ process.

In order to coerce, we must somehow place air power in a position where it can achieve maximum effect. Air power is, despite increasing technological improvements, still essentially a blunt instrument. It destroys mainly large and static targets.27 But blunt instruments can force an enemy into a dilemma. Leonhard refers to one classic land warfare dilemma:

The introduction of the chariot led to revolutionary tactical changes...[W]arfare previously had been conducted by men on foot.[This] for the most part demanded that the troops be packed into dense comparatively unwieldy blocks ...[and] the introduction of the arrow-shooting chariot put such formations on the horns of a dilemma, compelling them to carry out two contradictory movements at once. If infantry stayed together they would come under long distance fire to which they had no counter, and for which, moreover, they represented an ideal target. If, on the other hand, they took the opposite course and dispersed, they would be easily overrun.28

Classic interdiction, despite the advances in technology, may actually become more difficult.29 Synchronisation of effect will therefore need to be coupled with reach and precision. To deny the adversary the ability to adapt, we must present multiple dilemmas—and not just in the military realm. Coercion theory also demands that we offer up dilemmas. Yet, do air power planners just modify Warden’s rings or take another approach to achieve maximum effect, and how do we accomplish this in the complex warfighting realm?

Close Air Support

The answer lies in an often-neglected application of air power—close air support. It is apparent from reviews of literature, in particular those concerning the Korean War, that close air support has been a role which has suffered in peace but has been brought to a high level of skill by Western air forces in times of war.

For the modern ground commander, close air support is not a case of ‘if’ but rather ‘when’, and it is not in the classic model of 30 minutes prior to H-hour. Responsiveness is required both throughout the depth of an Area of Operations (AO)—easier with reach and precision—and temporally, which is not as easy, as persistence of air assets remains a problem unless you own large or numerous combat aircraft.30 Pervasive intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR), not necessarily airborne, appears also to be an as yet unfactored close air support requirement.31 Here the greatest gaps lie, but so too do the best opportunities present themselves.32 Indeed, pervasive and cued ISR facilitates all aspects of air power.

The First Gulf War provided the classic conventional dilemma. If Iraqi forces moved, air power would detect and destroy them; if they remained static, they risked being literally out-manoeuvred by conventional and special land forces33—the unsolvable dilemma.34 This example blurs the lines between what is classic close air support and battlefield air interdiction; however, we need to present this dilemma to the adversary in the complex warfighting domain. The vital need for close co-ordination of close air support with land manoeuvre forces is the tactical clue we need to apply at the operational and strategic level.35

Integrated close air support has the potential to provide immediate tactical effect that helps mitigate the strategic ‘ripple’. Minimum-mass tactics have one inherent weakness: they are extremely vulnerable when compromised or disrupted. A sustained air presence offers a greater possibility for protecting ground forces, both in offensive and defensive manoeuvre. Ground forces work at a level far more likely to achieve detection. Any attempt by the guerrilla to raise their level of effect by massing to counter our own minimum-mass tactics further increases their detection threshold and allows the easier application of air power. Any attempt by the guerrilla to lower their threshold reduces their ability to apply effect at a meaningful level or, at the very least, slows their tempo. This allows time in a long conflict to cue the necessary and vital non-military solutions needed to win.

Pape also contends that, in any combat operation, hitting the combatant hurts more than most air power theorists centred on Giulio Douhet will concede.36 Defence forces do just that—defend a nation or even just the idea of a nation. Even a rag-tag militia will protect its popular base or face being disenfranchised by its people. Military power is part of any national power model and, in wartime, combatants remain legitimate targets until disabled. While they remain effective, you can hit them and hit them hard. Without spilling into the morally bankrupt analogy of ‘bleeding an army white’, the degradation of any military power (regular or irregular) will profoundly affect the enemy, albeit for a short period of time.

Whilst more mobile and harder to detect than other targets for air power, military targets can be shaped by direct military action (land- or air-based) into a change of posture and this can raise the detection threshold for a further response. Synchronisation of land/air action offers the promise of throwing the enemy into a decision cycle that they can neither contain nor control. Tactical defeat leads to operational effect, which will enable strategic ends.

What is probably holding air power back in the close air support domain is neither technology nor over time training, but rather a mindset:

The lower the intensity of a conflict, the more the outcome depends on ground forces. Winning ‘the hearts and mind of the people’ is best achieved face to face. Therefore, in counter-insurgency/guerrilla wars or against an enemy who lacks a fully mechanised conventional force, air will normally support ground manoeuvre.37

Despite the quality of the remainder of Jack B. Eggington’s work, in this instance he could not have made a more dangerous statement. This is the conventional view of war. To coerce the jihadist, we must offer up the same dilemma that we impose on the conventional enemy, regardless of the level of war.

Conclusion

Reach and precision will matter, but enduring, rapid and pervasive effect will be just as important, not only with respect to applying conventional air power but also employing ISR assets. Synchronised ground and air reconnaissance will lower the detection threshold and rapid response must occur when required; on-time and on-target is not enough, it must be on-occurrence. Mass will not be as critical as causality. To provide a dilemma to the jihadist, we must not allow them sanctuary or respite. Such operations require endurance and continued presence. Coercion through rapid response and enduring containment will push systems to the limit.

There seems to be a lack of understanding in the extant RAAF doctrine that, now and into the future, tactical effect will echo into the halls of strategy. What should be said is:

In all forms of conflict, at all levels of war, the outcome depends on a synchronised joint force. Coercing your adversary and ‘shaping hearts and minds’ is best achieved face to face with the promise and presentation of potent threat. Therefore, in future wars, at all times air and land power must be mutually supporting.38

It is unlikely to remove the requirement for the airman and the soldier to take great risks when operating in or above complex terrain and this will not stop the new enemy from initially taking up arms. However, it is likely to ensure that the military component of a solution to any conflict is executed with maximum effect and with minimal loss of life on both sides. So reach and precision are not enough. Endurance, speed of response and the operational art are the new challenges for air power. These challenges are only partially solved by the promise of high technology. Most have to be met in the minds of those that plan and execute air warfare. Are you ready for the challenges that await?

Endnotes

1 RJ Hamilton, Green and Blue in the Wild Blue: An Examination of the Evolution of Army and Air Force Airpower Thinking and Doctrine since the Vietnam War, School of Advanced Airpower Studies, Air University, AL, June 1993, p. xxv.

2 Stephen King, The Running Man, Penguin, NY, 1996, first published under the pseudonym of Richard Bachman, Signet, NY, 1982.

3 EM Grossman, ‘The Halt Phase hits a Bump’, Journal of the Air Force Association, April 2001, Vol. 84, No. 4, pp. 34–36.

4 RE Simpkin, Race to the Swift, Brasseys, London, 1985, p. 289.

5 Australian Army, Future Land Operating Concept: Complex Warfighting, May 2004, <http://www.defence.gov.au/army/lwsc/Publications/complex_warfighting.pd…;

6 G.W. Goodman Jr, Lethal Lineup ISR Journal, September 2004, p. 24.

7 Sanu Kainikara, Future Employment of Small Air Forces, Air Power Development Centre Paper Number 19, August 2005, <http://www.defence.gov.au/RAAF/airpower/html/publications/papers/apdc/a…;

8 AVM Angus Houston cited in Thomas, T.J., Air chief focuses RAAF on the ground’, Australian Defence Business Review, 31 August 2004, pp. 15.

9 Goodman, p. 22.

10 Royal Australian Air Force, AAP1000 Fundamentals of Australian Aerospace Power, Canberra, 2002, p. 164.

11 I do not assume away these issues in terms of their real difficulty, but they are worthy of a separate paper.

12 Major Lee K Grubbs, US Army, and Major Michael J Forsyth, US Army, ‘Is There a Deep Fight in a Counterinsurgency?’ Military Review, July-August 2005, pp. 28–31, <http://usacac.leavenworth.army.mil/CAC/milreview/download/English/JulAu…;

13 J Warden, Planning to Win, Air Power Studies Centre, Paper No. 66, Canberra, ACT, July 1998, p. 16.

14 R Grant, ‘Nine Myths about Kosovo’, Air Force Magazine Online, June 2000, Vol. 83, No. 6, available at <http://www.afa.org/magazine/June2000/0600kosovo.asp>, accessed 20 October 2006.

15 Robert Pape, Bombing to Win: Air Power and Coercion in War, Cornell University Press, 1996, p. 3.

16 Ibid, p. 314.

17 Ibid, p. 4.

18 ST Hosmer, The Conflict over Kosovo: Why Milosevic decided to settle when he did, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA, 2001, p. xxi.

19 D Byman, M Waxman and EV Larson, Air Power as a Coercive Instrument, RAND Report, MR-1061, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA, 1999, p. xiii.

20 Ibid, p 130.

21 J.E. Peters, ‘A potential vulnerability of precision strike warfare’, Orbis, Vol. 48, No. 3, Summer 2004, p. 483.

22 Pape, Bombing to Win: Air Power and Coercion in War, pp. 4–5.

23 Ibid, p. 330.

24 E Dews and F Kozaczka, Air Interdiction, Lessons from Past Campaigns, N-1243-PA&E, Rand Report, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA, September 1981, p. viii.

25 J Mordike, The Korean War 1950–1953, Land-Air Aspects, Air Power Studies Centre, Paper No. 69, October 1998, p. 23.

26 PC Forage, ‘The Battle for Mount Pastrik: A Preliminary Study’, The Journal of Slavic Military Studies, Vol. 14, No. 4, December 2001, p. 72.

27 My intention is not to demean the importance of air transport, the rise of the utility helicopter and so forth, but these elements, although essential, remain at best supporting ones in the application of power, land, sea or air.

28 RL Leonhard. The Art of Maneuver: Maneuver-Warfare Theory and AirLand Battle, Presidio Press, Novato, CA, 1994, p. 96.

29 IO Lesser, Interdiction and Conventional Strategy: Prevailing Perceptions, RAND Report N-3097-AF, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA, 1990, pp. 43–44.

30 BW Don, TJ Herbert and JM Sollinger, Future Ground Commanders Close Support Needs and Desirable System Characteristics, RAND Report MR-833-OSD, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA, 2002, p. 113.

31 NK Molloy, Impact to Defence of Lessons Learnt using Modern Precision Strike Weapons, DSTO-GD-0360, DSTO Systems Science Laboratory, 2003, Executive Summary.

32 Don, Herbert and Sollinger, Future Ground Commanders Close Support Needs and Desirable System Characteristics, p. 122.

33 JB Eggington, Extract from ‘Ground Maneuver and Air Interdiction: A matter of mutual support at the Operational Level of War’, School of Advanced Air Power Studies, Air University, AL, May 1993, p. 29.

34 Ibid, p. 8.

35 For a very good account of the see-saw battle between CAS/BAI/Strike doctrine, see: Hamilton, Green and Blue in the Wild Blue: An Examination of the Evolution of Army and Air Force Airpower Thinking and Doctrine since the Vietnam War.

36 Giulio Douhet, The Command of the Air, Ayer Co Publishers, 1984, p 174. Douhet wrote in the context of doing away with the horrors of trench warfare, but this polarity has remained in much air power conceptual work.

37 Eggington, p. 22.

38 Author’s modification of existing doctrine; such words would greatly strengthen both AAP 1000 – The Fundamentals of Australian Aerospace Power and LWD 1 – The Fundamentals of Land Warfare.