Abstract

This article discusses a number of training and tactical lessons from the British Army’s Infantry Battle School. Key amongst these is the use of ‘immersion’ training ideologies to improve the effectiveness of infantry platoon commanders on operations and in the urban environment.

The Platoon Commander's Battle Course

The Platoon Commander’s Battle Course is an intensely demanding fourteen-week course, ten weeks of which are devoted to tactical training. The British training regime is based on a progressive sequence which moves from the ‘explain’ and ‘demonstrate’ phases to ‘imitate’ and ‘act’. Theoretical instruction is consolidated using the TEWT (tactical exercise without troops) as a means to further develop tactical acumen and bridge the gap between theory and field training. Demonstrations and syndicate modelling form a fundamental part of the first three weeks of the course. Platoon commanders embark on their first exercise in week four when, rather than assuming the role of platoon commander, they are mentored by a captain acting as the platoon commander. This method ensures that students are both mentored and led. The fifth week of the course includes a test exercise when the students are assessed both on their ability as a platoon commander and on their basic fieldcraft.

The course tempo intensifies in week six as the students are required to complete an arduous twenty-one kilometre march over the Brecon Beacons; demonstrate their tactical prowess on an assessed TEWT; produce a written exercise for their platoon; give a formal theory lesson on an aspect of military history or a current British military operation; and finally demonstrate their competence in calling in fire and directing the fire of a support company weapon detachment. The course’s ten-week tactical training phase is broadly outlined in Figure 1 below which also illustrates the progression of this phase through its modules.

These six weeks of training in barracks and in the local training area are merely a prelude to the mission rehearsal exercise which will take the aspiring platoon commander out of his comfort zone and test him over a demanding three-week period.

| Theory, demonstrations and TEWT | Exercise | Test Exercise | Test Week | Mission Rehearsal Exercise | Refit to Fight |

| Week 1-3 | Week 4 | Week 5 | Week 6 | Week 7-9 | Week 10 |

Figure 1: Broad course outline

Mission Rehearsal Exercise ('Immersion')

The mission rehearsal exercise closely replicates the scenario an infantry platoon commander might face if deployed on a short notice intervention operation. The scenario builds from day one of the course and is based on the deteriorating political situation within a fictitious African nation. The country slides into chaos with a failing internal security situation, border disputes with its neighbours, and squabbles over natural resources. Tensions continue to escalate until a mock United Nations Security Council Resolution is passed allowing armed intervention. A barrage of media coverage, intelligence summaries and operations orders prepare course members for a possible deployment. Mission-essential equipment and medical checks closely mirror those typical in a high readiness unit.

The readiness notice for course members—acting as the members of a rifle company—draws down rapidly and, within a six-week period, they find themselves assembled at an air point of disembarkation in Malawi being issued specific-to-mission equipment and receiving intelligence and operational briefings. Crucial liaison with the armed forces of the host nation takes place and these soldiers provide security during the deployment north to an area from which in-theatre training and forward reconnaissance can be undertaken.

The mission rehearsal exercise is initiated with a cross-border incursion by the belligerent country. The rifle company conducts a broad cross-section of tactical tasks in order to bring about a ‘lasting and peaceful solution’. The culmination is a three-day intense live firing exercise in which the company pursues the opposing force towards a ‘blocking position’ established by the host nation’s armed forces. The opposing force adopts a defensive stance, establishing a hasty security zone and main defensive zone. The student company conducts an advance to contact and a series of hasty attacks against the security zone over a time period of five hours. Once the security zone is breached the company conducts a deliberate attack to destroy a trench system and finally assaults a village.

The course’s young officers, preoccupied with multiple tasking and competing priorities, are placed under further stress dealing with the local inhabitants of the training area in Malawi. While friendly, these locals are extremely inquisitive and must be kept out of harm’s way in a firm but courteous manner. Maintaining this friendship is crucial to the success of the operation. The locals are not controlled by the exercise staff but are free to act in a way consistent with non-combatants in any war-affected country. The intrusion of other non-combatants including non-government organisations add to the realism of the training activity. Liaison must be sustained and friendly relations maintained with the host nation at all times. Language and cultural differences must be acknowledged and overcome.

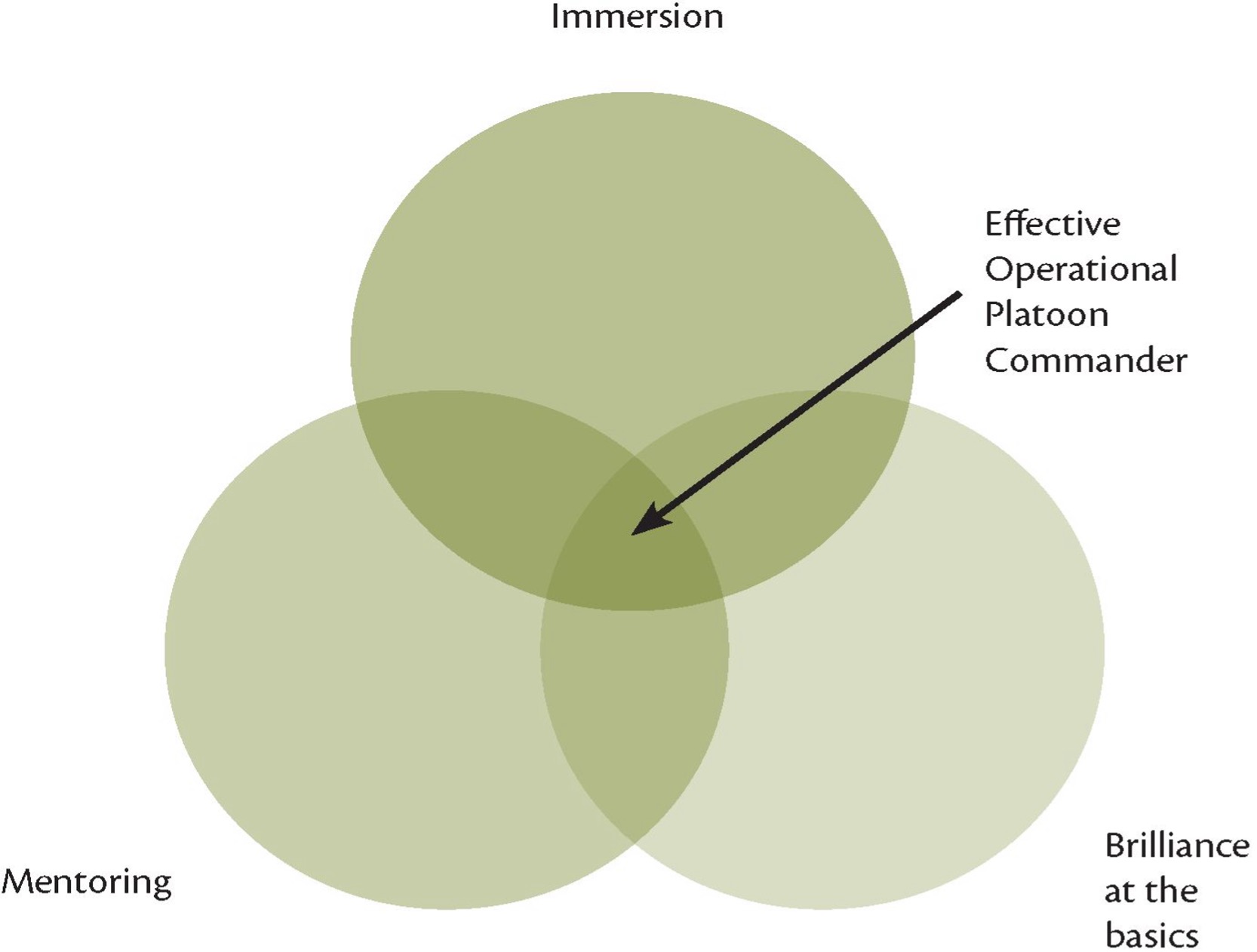

The mission rehearsal exercise uses three key pillars to develop the student: mentoring, immersion and ‘brilliance at the basics’.1 The relationship between these three pillars and the course endstate is fundamental and defining and is illustrated diagrammatically in Figure 2.2 While mentoring is a well-accepted training technique in Australia, immersion training is at the cutting edge of training theory. To transport a company of young officers to Africa, immerse them in a tactical situation with the competing interests of a deteriorating political situation, armed conflict, non-government organisations, host nation’s armed forces and local non-combatants’ interests and security, as well as inflicting on them the severe climatic differences between Britain and Africa, is compelling to say the least. This form of training is pitched at a level of intensity not found in most field exercises. Further, the young officer cannot ‘hide’ from his responsibilities; a colour sergeant is there to continually mentor, cajole and harass him to achieve a level of ‘brilliance’ in his basic infantry skills. Thus, the three pillars of the exercise form a symbiotic circle, as illustrated in Figure 2.

The benefits of the mission rehearsal exercise as a training medium are intuitively obvious. The real difference between this approach and others lies in the immediate and tangible benefits realised on operations. Anecdotal evidence ranging from two star level down to the platoon commanders themselves testifies to the success of this training on operations. Platoon commanders who have undergone this type of training are far more competent and confident in their own ability. They make better, more reasoned decisions under situational and time constraints. For young infantry officers who have completed this exercise, the ‘three block war’3 seems to hold far fewer cognitive challenges. In addition, like the ‘strategic corporal’, the infantry platoon commander who completes this exercise is fully aware that ‘his judgement, decision-making and action can all have strategic and political consequences that can affect the outcome of a given mission and the reputation of his country’.4

Urban Operations Tactics and Training

Urban operations training is the other stand-out feature of training at the British Infantry Battle School. This training is based on current doctrine, conducted in excellent facilities and features the rapid integration of operational lessons into training. Urban operations training emphasises individual and small team skills as the cornerstone of success in the urban environment. Whether in attack or defence, the individual and small team must be adept at basic urban tactics. Fire team, section, platoon and company entry drills; two-man room clearances; an ability to defend or harden positions against the enemy and to act within the section, platoon and company design for battle—these are integral components of urban operations training. Three days in week four and four days in week five of the platoon commander’s course are dedicated to this training. Many hours are spent in theory lessons, in ‘rock’ drills, and in cutaway buildings watching demonstrations and practical exercises. The end result is an infantry platoon commander who is fully conversant with his role both as an individual and as a leader.

Figure 2: The three training pillars

The use of the combined arms teams with armour in an urban environment is a well-established practice. Like the US Marine Corps in Iraq,5 the British experiences in Iraq and on exercises at training facilities such as Copehill Down and Imber Village emphasise that ‘there is no opposition that could not be overcome by well-trained and well-equipped combined arms teams’.6 While most military professionals are quite comfortable with this concept, many become unsure when confronted with the next tactical decision—at what level of command the grouping occurs. During exercises on the platoon commander’s course, grouping involved the allocation of an individual tank to an armoured or mechanised infantry section. While this notion of splitting tank troops and squadrons is quite alien to many, the reality is that the very nature of urban terrain makes it difficult to concentrate a tank force. Grouping at such a low level allows the attacker to overcome the imbalance in the relationship between suppression and manoeuvre often experienced by the infantry sub-unit.7 A structural or materiel solution to redress this imbalance may not be necessary; the solution could well lie in the use of the strengths of the combined arms team, including its integral firepower and protection, to re-balance the force. While this is not the panacea for every eventuality in the urban environment, it is an option well worth considering.

The Warrior armoured vehicle has proven its worth both in training and operations. It has performed extremely well on operations in Iraq and is very effective in urban terrain. The author’s discussions with members of the 1st Battalion, The Princess of Wales’ Royal Regiment, have engendered the very strong impression that few other vehicles in the world could have performed as well during the uprisings in Iraq in August 2004.8 The proliferation of hand-held anti-armour weapons and the simple yet effective tactic of targeting one vehicle with multi-weapon systems from several firing points simultaneously made this a complex scenario. The situation was exacerbated by the complexity of the terrain and the level of ‘clutter’ found in the towns and villages of the province. Through all of this the Warrior armoured vehicle performed superbly. The general opinion within this particular infantry battalion was that only a vehicle with the Warrior’s level of protection, firepower and mobility could be effective against this type of attack in urban terrain. This lesson is being incorporated directly into training as students are presented with the advantages and limitations of the employment of ‘Saxon’ (mechanised infantry), ‘Snatch’ land rovers or land rovers (light infantry) in this terrain against an organised asymmetric threat.

Conclusion

The training conducted by the British Army’s Infantry Battle School is highly effective. The Platoon Commander’s Battle Course is a demanding and intense learning journey for its participants. They are truly fortunate to receive benchmark training through mission rehearsal exercises and urban operations instruction. The mission rehearsal exercise, in particular, is extremely impressive and forms a logical extension of the course material and current British strategic thought. British infantry officers must be able to deploy at short notice, acclimatise and adapt quickly to a new environment, and then aggressively and competently apply military judgement to combat a given threat. The course slowly builds towards this crescendo and places the students under a significant amount of perceived and real stress. The urban operations training is well developed and effective, recognising that current doctrine informed by lessons identified on operations is the way forward. Young officers are also made acutely aware that it is through adherence to the basics that they will achieve success in this most complex environment. They are exposed to armour within the combined arms team and given the opportunity to experiment with ideas and concepts for its effective employment. Training at the Infantry Battle School is unquestionably world class and is providing the British Army with young officers ready to deploy on operations now. This is a model the Australian Army would do well to examine and, with some consideration for local conditions and operational requirements, indeed choose to emulate.

Endnotes

1 This phrase captures the Australian—and now British—ethos of competency in the low-level skills as the key to mission success.

2 This is the author’s own model based on the key ideas of the mission rehearsal exercise.

3 The three block war is a well-accepted US Marine Corps concept. The British believe that they are very much involved in a three block war in Iraq.

4 Major Linda Liddy, ‘The Strategic Corporal’, Australian Army Journal, Vol. II, No. 2, Autumn 2005, p. 139.

5 Lieutenant Colonel John Simeoni, ‘Some Observations of US Marine Urban Combined Arms Operations in Iraq’, Australian Army Journal, Vol. II, No. 2, Autumn 2005, p. 94.

6 Ibid.

7 Lieutenant Colonel David Kilcullen and Captain Ian Langford have written some excellent articles on the basis of infantry close combat. Both have discussed materiel and structural changes to the way infantry platoons and companies fight the close battle. This author is suggesting that increased firepower for light infantry platoons will always be welcomed but it comes at a cost, i.e. additional weight for the soldier. Infantry grouped in combined arms teams utilising the effects discussed by Captain Langford comprises a simple solution for any capability gap for the infantry in close combat.

8 In August 2004, the Madhi Army or Militia, as it sometimes called, instigated uprisings in the Maysan Province of Iraq. The British Army hierarchy considers this to be some of the most intense fighting seen by British forces since the Falklands War. It was far more intense than the fighting which took place in the Battle for Basra in June 2003.