Abstract

Has contemporary strategic thought really not produced a significant idea, concept or thinker in the last half-century? The author argues that van Creveld’s proposition is distinctly unfair to the contributions of a number of other modern military writers. This article refutes van Creveld’s argument through a survey of post–Second World War strategic thought. It explores the continuing evolution of military theory through the contributions of five principal contemporary military strategists: John Boyd (1927–97), Michael Howard (1922–), Edward Luttwak (1942–), Colin S Gray (1943–) and, of course, van Creveld himself (1946–).

Introduction

The Israeli historian, teacher and military theorist, Martin van Creveld, contends provocatively that the quality of contemporary Western strategic thought has declined significantly since the Second World War. In his eyes, largely as a consequence of an unwillingness or inability to perceive and react to what he labels the ‘transformational’ nature of modern war, there has been in recent decades a conspicuous lack of innovative thinking about warfare and warfighting. Van Creveld concludes that:

ninety per cent of so-called strategic writing since 1945 ... was not about strategy at all. It was about how to incorporate or integrate various kinds of new weapons and weapon systems ... there was nothing in the 1991 [Gulf War] campaign that Patton could not have done in a very similar fashion back in 1944.1

In one sense he is correct in both this general observation and his explanation for it. It is indeed impossible to identify a modern day strategist of the fame, insight and influence of a Sun Tzu, a Jomini or a Clausewitz. Nor is it easy to select a current military theorist with levels of originality or conviction comparable to the pre–1939 efforts of JFC Fuller or Basil Liddell Hart. On another level, however, van Creveld’s suggestion that the evolution of Western strategic thought has somehow plateaued or stagnated since 1945 goes too far. In making this proposition, not only does he overstate the trend but he is being distinctly unfair to the contributions of a number of other modern military writers—including himself. Strategic theory may not have progressed since the Second World War in the giant leaps of ages past, but this does not necessarily signify its decay.

The purpose of this article is to refute van Creveld’s argument through a survey of post–Second World War strategic thought. It explores the continuing evolution of military theory through the contributions of five principal contemporary military strategists: John Boyd (1927–97), Michael Howard (1922–), Edward Luttwak (1942–), Colin S Gray (1943–) and, of course, van Creveld himself (1946–). These individuals, chosen for the importance and likely enduring nature of their ideas, represent a varied cross-section of thought.2 Each has extended the traditional modes of strategic thought beyond their well-established—often Clausewitzian—foundations. It is true that many of the basic tenets of conventional Western military strategy have been challenged since 1945. In many cases, old ideas have been found wanting—especially when uncritically applied to conflicts whose nature would have been alien to the strategists of ages past. At the very least, however, the five individuals explored in this article, through their novel approaches to old paradigms or their recognition of new ones, prove that the progression of strategic thought, while perhaps temporarily subdued, has not ceased. Nor is it likely to cease until the end of warfare or the end of us all—that is, whichever comes first.

Strategy

To properly assess the contributions of the strategic thinkers discussed in this article, a working definition of what is meant by ‘strategy’ is required. At its heart, and in any context, strategy describes a relationship between actions and objectives. The word expresses nothing more or less than the plan, means or method whereby singular events are linked and/or coordinated to achieve overall goals. Any activity involving some form of competition will inevitably contain an element of strategy. Strategy is the plan, for example, by which chess pieces are moved to checkmate an opponent. It is the linkage, in another sense, whereby the actions of individual players on a football team are coordinated to outscore an opposing team. When dealing with issues of armed conflict, when the competition in question is war, strategy becomes the plan by which military operations achieve national political goals. Colin Gray describes it as the theory and practice of the use of organised force for political outcomes and a ‘bridge that relates military power to political purpose.’3 Gray’s ‘bridge’ is an important analogy as it not only describes the link between ends and means but also the reciprocal influence, through strategy, that operations and objectives constantly exert on each other.

The conception of military strategy as the plan for linking and translating battlefield events into victory in war has a distinguished pedigree. A number of notable ‘strategists’, some of whom are discussed in detail in this article, have embraced this definition. The nineteenth-century Prussian theorist Carl von Clausewitz saw strategy as ‘the use of the engagement for the purpose of the war’ while the twentieth-century British military thinker, BH Liddell Hart, described it as the application of military means to fulfil the ends of policy.4 In the twenty-first century, the US Army War College defines military strategy as the ‘skilful formulation, coordination, and application of ends (objectives), ways (courses of action) and means (supporting resources) to promote and defend the national interest.’5 Clearly military strategy remains the link between operations and objectives—the means by which war actions achieve war aims.

At this stage it is important to note that a working conception of military strategy is often undermined by the colloquial misuse of the term. Military strategy does not, for example, describe tactics. If strategy is the art of linking battles to win the war, then tactics are the techniques and methods used to achieve success in those battles. Too often the issue is confused when terms like ‘operational strategy’ are substituted for ‘tactics’. Equally, military strategy is not ‘grand strategy’. The latter term is regularly and incorrectly used to describe the set of plans and policies designed to achieve the ‘national interest’ or national objectives—most of which will have nothing to do with the use of military force. Military strategy may be a subset of grand strategy, but the terms are not interchangeable.

John Boyd

Of the Cold War and post–Cold War theorists who have shaped the development of modern strategic thought, principal among them was the US fighter pilot, Colonel John Boyd. While he never actually published a book on strategy, Boyd derived a set of ideas that have been collated and disseminated widely as a series of several hundred ‘slides’ entitled: Discourse on Winning & Losing. The impact of Boyd’s concept of war and warfighting has been widespread—particularly in the US where he was credited, according to popular anecdote, with developing the essential elements of the Coalition military strategy in the Gulf War of 1991. Indeed, the Commandant of the US Marine Corps, General Charles Krulak, wrote a eulogy to Boyd in 1997 describing how ‘the Iraqi army collapsed morally and intellectually under the onslaught of American and Coalition forces. John Boyd was an architect of that victory as surely as if he’d commanded a fighter wing or a manoeuvre division in the desert.’6

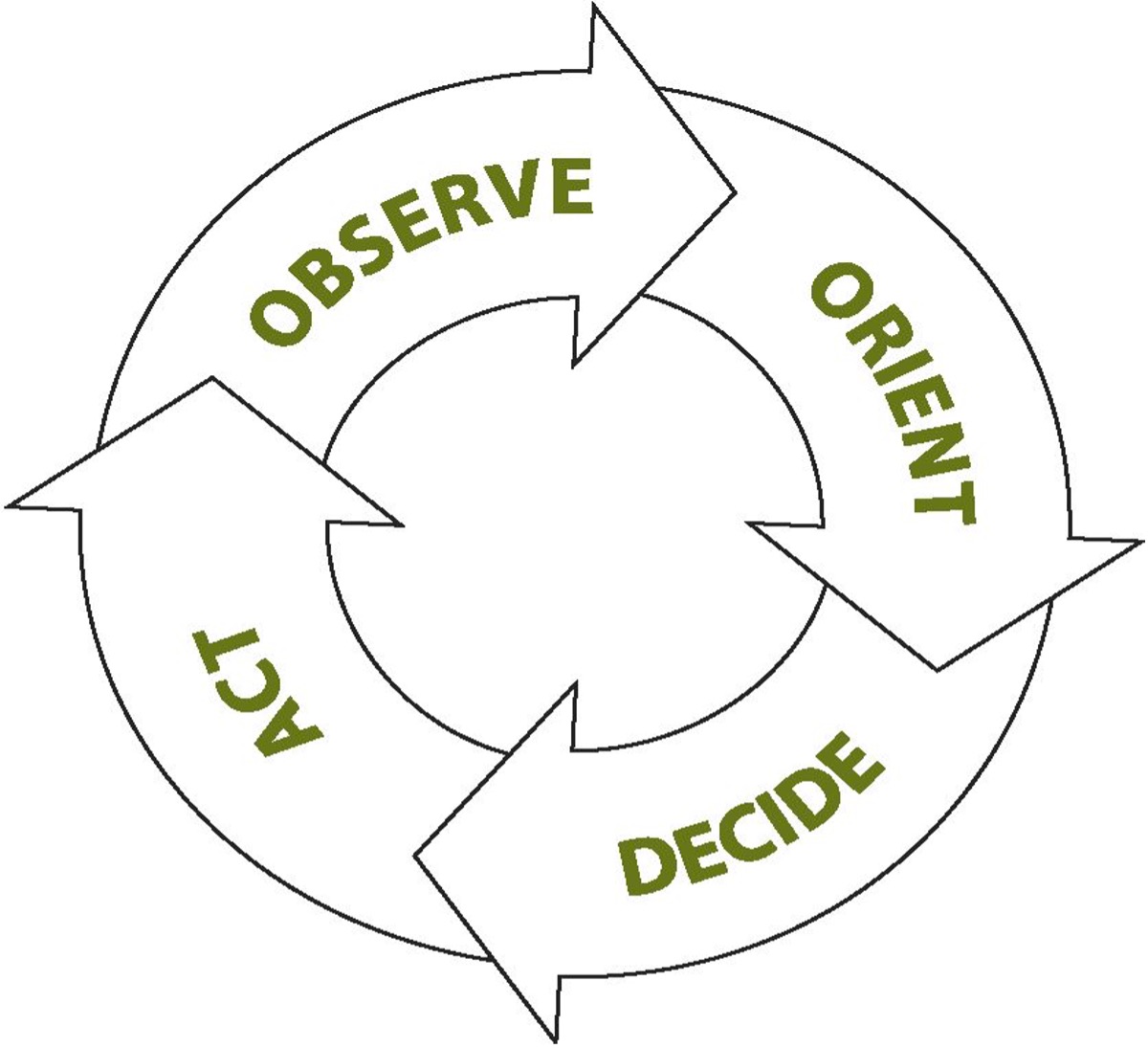

For Boyd, the strategic game is one of interaction and isolation.7 His key strategic idea, therefore, was the concept of the Observation, Orientation, Decision, Action (OODA) Loop. According to this theory, Observation is the collection of data concerning the environment or ‘battlespace’. Orientation is the synthesis or analysis of that data to form an accurate mental picture of that environment. Decision is the determination of a course of action based on that mental picture. Action is the physical execution of a decision. According to Boyd, the OODA Loop is the process by which any entity reacts to any given situation—be it an individual fighter pilot involved in aerial combat or an entire nation at war.

The process of cycling through the OODA Loop is continuous. The simple key to victory, therefore, is to move through this process faster and more accurately than the adversary. In order to win, a force must operate at a faster tempo or rhythm than an adversary and ‘OODA more inconspicuously, more quickly, and with more irregularity as a basis to keep or gain initiative.’8 In doing so, decisions are made more rapidly and the enemy is forced to become reactive rather than proactive. The heart of Boyd’s theory suggests that it is speed of decision-making that allows a friendly force to ‘get inside’ an adversary’s OODA Loop, rendering the opponent psychologically and intellectually dysfunctional. Without a brain, the body or physical form of an enemy’s military establishment is irrelevant and doomed to paralysis and defeat. The opponent is folded ‘back inside himself so that he can neither appreciate nor keep up with what’s going on ... thereby collapsing] his ability to carry on.’9 Under Boyd’s paradigm it is the singular function of all strategy to bring about situations where an enemy can be ‘out-OODAed’.

Boyd explained his theory by situating it in history. He described how, for example, by exploiting superior leadership, intelligence, communications, and mobility, as well as by playing upon an adversary’s fears and doubts via propaganda and terror, the Mongols operated inside adversary observation-orientation-decision-action loops.10 Similarly, the ‘amorphous, lethal and unpredictable activity’, which characterised the German strategy of Blitzkrieg in the Second World War, and guerrilla warfare throughout the ages, ‘make them appear awesome and unstoppable which altogether produce uncertainty, doubt, mistrust, confusion, disorder, fear, panic, ... and ultimately collapse’.11

Figure 1: The command and control process: The OODA loop.

Two central aspects of Boyd’s OODA Loop stand as important influences on modern strategic thought. The first is that all large military organisations contain these decision-action cycles at the tactical, operational and strategic levels of war. Second, in order to achieve an efficient OODA Loop process, capable of cycling at a faster rate than the enemy, modern militaries need to embrace a decentralised approach to command. Echoing the line of thought upon which the famously successful nineteenth-century Prussian General, Helmuth von Moltke (the Elder) (1800–91) modelled his General Staff, Boyd advocated a type of ‘directive control’ whereby subordinates are made aware of their superior’s intent and objective but remain free to decide how best to achieve it. This approach, in contrast to detailed, proscriptive and process-driven orders, allows subordinate commanders to exercise initiative and take tactical and strategic opportunities as they are presented, rather than wasting time by constantly seeking higher approval. Such a command organisation greatly increases organisational flexibility and adapts/ reacts to situations far quicker than traditional structures. For Boyd, for example,

the secret of the German command and control system ... lies in what is unstated or not communicated with one another – in order to exploit lower level initiative yet realise higher level intent, thereby diminishing friction and reduce time, hence gain both quickness and security ... the Germans were able to quickly get into their adversaries OODA loop.12

Importantly, Boyd noted that the necessary foundation of this command model was mutual trust. Superior headquarters are required to have faith in their subordinate’s abilities and judgment while junior commanders need to feel confident that their seniors are setting the right objectives to begin with.

As well as describing a model whereby an efficient OODA Loop could be created and sustained within a friendly force, Boyd also suggested a number of ways to disrupt the decision-making cycle of the enemy. To this end he divided war itself up into three distinct elements. First, ‘moral warfare’, which concentrates on breaking down the adversary’s will to win by promoting doubt and internal fragmentation. Victory comes from playing upon moral factors that drain resolve, produce panic, and bring about collapse.13 Boyd’s second element, ‘mental warfare’, is where the key to success is distorting the enemy’s perception of reality (the observation and orientation phases) through deceit or direct attack against communications/information capabilities. Particularly useful in the mental battle are surprise and shock, which can be represented as an overload beyond an adversary’s immediate ability to respond or adapt.14 The last of Boyd’s three elements of war, ‘physical warfare’, is where the destruction of the enemy’s physical presence and means of war-making undermines the OODA Loop (action phase). The idea behind the physical battle is to ‘diminish [the] adversary’s capacity for independent action ... or deny him the opportunity to survive on his own terms, or to make it impossible for him to survive at all.’15 It is perhaps fitting to allow Boyd himself to describe the cumulative effects of military action based on his theoretical model. Such strategies:

operate inside adversary’s OODA loops, or get inside his mind-time-space to create a tangle of threatening and/or non-threatening events/efforts ... [they] enmesh an adversary in an amorphous, menacing, and unpredictable world of uncertainty, doubt, mistrust, confusion... beyond his moral-mental-physical capacity to adapt or endure.16

Michael Howard

While Boyd focused on operational warfighting methodologies, other contemporary theorists, like the British military historian Sir Michael Howard, were concentrating on wider strategic issues. Howard’s primary contribution to the evolution of modern strategic thought is through an expansion of the study of military history beyond chronicles of battles to include the wider sociological implications of war. His early account of the Franco–Prussian War (1870–71), for example, demonstrated how the conflict was in many ways a reflection of late nineteenth-century French and German societies. Howard saw the study of this conflict as ‘transcending the specialist field of the military historian, or even the historian of nineteenth century Europe.’17 With Clausewitzian insight, Howard showed the fundamental importance of politico-military relationships during the war: it was entirely due to Bismarck’s statesmanship that Moltke’s victories were not to remain as ‘sterile as Napoleon’s, but were to lead, as military victories must if they are to be anything other than spectacular butcheries, to a more lasting peace.’18 As a warning to present-day strategists, Howard stressed the danger of civil-military friction under the conditions of industrial war by predicting that had the Franco–Prussian War ‘been prolonged for a few more weeks it is difficult to see how either Bismarck or Moltke could have remained in posts which each felt the other was making untenable.’19

Howard’s later writings provide some important insights into the nature of modern military strategy. His basic thesis is that contemporary Western strategic thinking is flawed in its bias towards the operational aspects of war. While such a focus may well have been appropriate in the Napoleonic era, Howard contends that the experience of the past century demonstrates this approach to be inadequate and even dangerous.20 In its place he advocates a type of ‘inclusive strategy’, paying due consideration, in addition to the operational art, to the importance in war of logistic, social and technological influences. Howard contends that modern war is conducted in four dimensions: the operational, the logistical, the social and the technological. No successful strategy can be formulated that does not take account of them all.21

Blaming Clausewitz for the artificial division of strategy into logistic and operational elements—and the subordination of the former to the latter (perhaps understandably in the context of his Napoleonic Wars)—Howard concludes that no campaign can be understood or interpreted unless its logistical problems are studied as thoroughly as the course of operations.22 Indeed, the omission of logistical considerations by most historians and strategists has ‘warped their judgements and made their conclusions in many cases misleading.’23 In support of this position he suggests, for example, that

Moltke’s successes were not due to any brilliant generalship... the German victories, as was universally recognised, had been won by superior organisation, superior military education, and, in the initial stages of the war at least, superior manpower; and it was these qualities which would bring victory in future wars ... The military revolution which ensued in Europe had repercussions in spheres far transcending the military.24

Similarly, despite the fact that many of the Southern Generals during the US Civil War ‘handled their forces with a flexibility and imaginativeness worthy of a Napoleon or a Frederick; nevertheless they lost’—they lost to the inevitable consequence of the North’s capacity to mobilise superior industrial strength and manpower into armies, the size of which rendered the operational skills of their adversaries almost irrelevant.25 To Howard, this conflict was a clear case where the logistical dimension of strategy proved more significant than the operational.26 So too, according to Howard, the logistical and technological capacity of the Allies in the Second World War ‘rendered the operational skills, in which the Germans excelled until the very end, as ineffective as those of Jackson and Lee.’27

Apart from advocating an increased emphasis on logistical considerations in the formulation of modern strategy, Howard also points to Western neglect of the social aspects of war. This means that, among other issues, the management of, or compliance with, public opinion has become an essential element.28 For him, in modern war it is society that provides the commitment and determination that enables the application of logistic advantage. Pointing again to history, Howard suggests that ‘the Franco–Prussian War in particular was won, like the American Civil War, by a superior logistical capability based on firm popular commitment.’29 This requirement for social dedication, as a pillar of modern strategy, applies equally to the effectiveness and credibility of strategies of deterrence and coercion—without it, their real and implied threats are not only empty but, more importantly, can be perceived as being empty. Howard also applies his ideas on the forgotten social aspect of strategy to the problem of insurgency warfare faced by many Western militaries in the post-1945 period. He believes that it was the inadequacy of the socio-political analyses of the societies with which these militaries were dealing that lay at the root of many notable failures, despite overwhelming operational and logistical advantage.30 Accustomed to operationally-focused strategies, Western theorists have mistakenly sought operational solutions to what were essentially conflicts on the social plane.31 Of all Howard’s contributions, it is perhaps this last insight which will resonate most loudly in the twenty-first century. The social sources, ramifications, and implications of the ‘Global War on Terror’, and ongoing operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, for example, are ringing endorsements of Howard’s criticism of operationally-oriented military solutions to socially and politically-oriented strategic problems.

Edward Luttwak

Along with Howard, the Romanian-born economist, historian and scholar of international relations, Edward Nicolae Luttwak, is one of the most outstanding present-day strategists. He has a reputation for the unorthodox, earned initially through his controversial interpretations of the role of foreign power intervention in regional conflict in Coup d’etat: A Practical Handbook (1968), and of ancient Roman frontier strategies in The Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire from the First Century AD (1976). Luttwak’s most important contributions to modern strategic theory, however, are contained in Strategy: The Logic of War and Peace (1987), in which his stated purpose was to ‘define the inner meaning of strategy’ and ‘to uncover the universal logic that conditions all forms of war as well as the adversarial dealings of nations even in peace.’32

Luttwak’s central thesis concerns the inherent paradox of warfare and strategy. He does not reflect the counter-Enlightenment tradition represented by nineteenth-century Prussian officer, Heinrich von Berehorst (1733–1814)—and others before and since—who posit that the inherent unpredictability of strategy renders it impervious to productive analysis. Rather, Luttwak contends that strategy must be understood as a unique field of human endeavour in which paradoxical logic is not only required but rewarded. He writes: ‘it is only in the realm of strategy, which encompasses the conduct and consequences of human relations in the context of actual or possible armed conflict, that we have learned to accept paradoxical propositions as valid.’33 The basic idea of deterrence, or maintaining peace by preparing for war, is an example of this general principle. Luttwak goes further than this, however. He suggests that strategy does not merely entail this or that paradoxical proposition; instead he believes that the entire realm of strategy is pervaded by a paradoxical logic, which induces ‘the coming together and reversal of opposites ... to reward paradoxical conduct while defeating straightforward logical action.’34 To illustrate the point fully, he asks readers to:

[c]onsider an ordinary tactical choice, the sort frequently made in war. To move towards its objective, an advancing force can choose between two roads, one good and one bad, the first broad, direct and well-paved, the second narrow, circuitous and unpaved. Only in the paradoxical realm of strategy would the choice arise at all, because it is only in war that a bad road can be good precisely because it is bad and may therefore be less strongly defended or even left unguarded by the enemy... instead of A moving towards its opposite B, A actually becomes B and B becomes A.35

Along with investigating the intrinsic paradoxical nature of war, Luttwak provides some valuable insights into more specific aspects of modern strategy. With a focus on conventional operations, he describes two general approaches: attrition and ‘relational manoeuvre’. He notes the former is war waged by industrial methods, where the enemy is treated as nothing more than an array of targets and the aim is to win by their cumulative destruction achieved with superior firepower and material strength.36 Under the attritional paradigm, ‘process replaces the art of war’.37 Luttwak warns against such strategies because there can be no victory in this style of war without an overall material superiority, and there can be no cheap victory as might be achieved with clever moves with few casualties and few resources expended.38 Having said this, under strategies of attrition, provided for whatever reasons the enemy is forced to fight symmetrically (as opposed to adopting guerrilla, terrorist or other asymmetric methods), victory is assured by material superiority.

Luttwak’s alternatives to attrition-based approaches are those involving relational manoeuvre. He regards such strategies as an encapsulation and exploitation of war’s paradoxical nature as they rely, inherently, on the surprise achieved by paradoxical decision-making. Luttwak contends that ‘to obtain the advantage of an enemy who cannot react because he is surprised and unready... all sorts of paradoxical choices may be justified.’39 Under such strategies,

instead of seeking out the enemy’s concentrations of strength to better find targets in bulk, the starting point of relational manoeuvre is the avoidance of the enemy’s strengths, followed by the application of some particular superiority against presumed enemy weakness, be they physical, psychological, technical or organisational.40

The aim is not to destroy the enemy’s physical substance as an end in itself, but rather to incapacitate by some form of systematic disruption.41 Such characteristics mark Luttwak’s relational manoeuvre, therefore, as a direct extension of Liddell Hart’s indirect approach and a close cousin to contemporary airpower theories of strategic paralysis.

One of Luttwak’s key strengths is that, unlike Liddell Hart, he did more than present relational manoeuvre as a universal strategy of choice—he also acknowledged its weaknesses. First and foremost, Luttwak accepted that all paradox-based decision making, all efforts at surprise and deception aimed at avoiding enemy strengths, will inevitably ‘have their costs, regardless of the medium and nature of combat.’42 Such a price will in most cases involve a decrease in physical strength. Following the ‘line of least expectation’ must entail forgoing the most attractive (and most obvious) military option. Whether traversing a longer path or more difficult terrain, sacrificing force elements to a deceptive effort, or any number of other paradoxical choices seeking to surprise the enemy, some measure of combat power must be sacrificed that otherwise would have been available. Taking this point further, Luttwak warns that the ‘paradoxical path of “least resistance” must stop short of self-defeating extreme.’43

The second enduring characteristic of war that Luttwak suggests will always work against strategies of relational manoeuvre, or any military method designed to match strength against weakness, is Clausewitzian ‘friction’. This is problematic because while the entire purpose of striving to achieve surprise is to diminish the risk of exposure to the enemy’s strength, this very act increases the danger of failure in implementing whatever is intended because friction grows exponentially ‘with any deviation from the simplicities of the direct approach and the frontal attack.’44

Luttwak is almost unique among strategists in that he brings balance to the argument between direct and indirect strategies: ‘the direct approach and frontal attack are therefore easily condemned by advocates of paradoxical circumvention who focus on the single engagement, seeing very clearly the resulting lessening of combat risk, while being only dimly aware of the resulting increase in organisational risk’—he understands the true nature of friction in war and reminds modern war fighters of its continuing relevance.45

Colin S. Gray

A fourth author and theorist whose work clearly signifies the progression of strategic thought in the contemporary era is Colin S Gray, Professor of International Politics and Strategic Studies at the University of Reading, England. Gray served for five years in the Reagan Administration on the President’s General Advisory Committee on Arms Control and Disarmament, and has advised both the US and the British Governments on defence and security-related issues. His ‘official’ work includes studies of nuclear strategy, arms-control policy, maritime strategy, space strategy, and the use of special forces. Gray is the author of a host of books and articles on ‘the theory and practice of the use, and threat of use, of organised force for political purposes in the twentieth century’—that is, on military strategy.46 Some of his most recent contributions include Modern Strategy (1999), Strategy for Chaos: Revolutions in Military Affairs and the Evidence of History (2002), The Sheriff: America’s Defense of the New World Order (2004), and Another Bloody Century: Future Warfare (2005).

Two of Gray’s latter books, Modern Strategy and Another Bloody Century, have made particularly important contributions to the evolution of contemporary military thought. He appreciates the complexities of historical processes and avoids an undue emphasis on ‘theory’ in his analyses. The key to his success is an interpretive, analytical and multi-disciplinary approach to the study of strategy. Gray argues that the past provides valuable insight for the strategic theorist, while reminding historians that the perspectives of other branches of scholarship are instructive. He uses such techniques in Modern Strategy and Another Bloody Century to offer suggestions on applying military force in an increasingly complex world. Aligning himself with Luttwak, for example, Gray refutes the idea that technology itself is any sort of ‘revolution’ or that it alone can or should dominate strategic thinking. Such technological infatuation, he believes, is expensive, susceptible to asymmetric attack and subversive of other elements of strategy that should be managed in harmony. He consistently questions what he considers to be a dangerous trend towards technological determinism in the West. In his latest work, Gray assesses the likely nature of future warfare, considering the role of weapons of mass destruction, space mounted-weaponry and cyber-warfare—all of which are seen as different forms of existing systems, not paradigm-busters.47

One of Gray’s most important contributions to the study of strategy comes from his understanding of the nuances of social-strategic culture and institutional practice. He contends that no person or institution operates ‘beyond culture’—not even the theorists and practitioners of war.48 In Modern Strategy, he goes to great lengths to explain the importance of strategic culture, defined as ‘a context out there that surrounds, and gives meaning to, strategic behaviour ...’, and describes US defence decision-makers, for example, as being pre-disposed to isolationism and abstract technical solutions to strategic problems.49 Importantly, in a warning for Western militaries and increasingly relevant in a range of contemporary conflicts, he concludes that a sound strategic culture with inferior weapons can defeat a weak strategic culture with an abundance of technology and economic power.

Another of Gray’s key contributions, and a theme that runs through a number of his works, is the idea that the foundations of strategy are essentially unchanging. In this he shows himself as essentially Clausewitzian, yet he extends and interprets the Prussian theorist for the twenty-first century. The ‘grammar’ of war may change, with advances in technology, mobility, weapons and so forth, but its ‘logic’ does not. Gray believes that many of the fundamental considerations and problems of strategy—the military/political balance, time, space, and human dimensions, etc—are enduring. Whilst he does not argue that war is unchanging, he demonstrates that little of real importance changes.50 He believes that ‘there is an essential unity to all strategic experience in all periods of history because nothing vital to the nature and function of war and strategy changes.’51 Such advice is a poignant reminder to those prone to overstating the revolutionary nature of the twenty-first century battlefield. Very few strategic problems, and very few of their solutions, are in fact ‘new’. Like Boyd, Gray pays particular attention to one of the truly ageless dimensions of strategy, unique for being immovable and unimprovable: time. Military theorists must acknowledge it and practitioners must utilise it. Time is a strategic dimension too little understood and consequently too little valued by many contemporary combatants.

In a further extension of Clausewitzian strategic thought, Gray agrees that warfare is best understood in a political context; he adds that this outlook, especially in the modern era, needs to be tempered by the light of cultural and social pressures. He urges modern military planners to consider strategy as not exclusively about force of arms, but rather about achieving the national political objective by winning a clash of wills. In this clash, and depending on the nature of the struggle, politicians and populations are often as important as military strength—and may even be more so. Militaries that continue to skew their force structure toward ‘conventional’ capabilities at the expense of all others are, therefore, on shaky ground. Military strategy must be situated in a balanced manner within the full range of national capabilities: diplomatic, economic, cultural, psychological and information-based. Gray also considers the issue of whether wars can be controlled at all; in some cases, he believes, they should not be, so that issues can be settled through conflict alone. In any case, war and warfare do not always change in an evolutionary, linear fashion, and attempts to regulate war are therefore inevitably problematic.

In his most recent work, Gray discusses the nature of future war by first warning about the perils of prediction, particularly those claiming that the nature of war has ‘changed’ in the twenty-first century. For Gray, there is no guarantee that state-based industrial warfare has disappeared from the strategic landscape. War is an inescapable human condition, albeit one capable of taking on a highly variable range of forms. According to Gray, although irregular warfare may dominate for some years, developments yet unforseen—such as a renewed and robust Sino-Russian partnership—may emerge to oppose the United States in a conventional military manner. He reflects that:

... the Cold War is barely fifteen years gone, yet it is already orthodox among both liberals and many conservatives to claim that major war between states is obsolescent or obsolete. If history is any guide, this popular view is almost certainly fallacious.52

At the same time, he concedes that most conflict in the immediate future will continue to be at the sub-state level and seeks to demonstrate, particularly in Modern Strategy, that the strategic principles of conventional war are valid and applicable to small- and sub-state conflicts. In doing so, he makes three important albeit contentious points: such conflicts are generally not resolved decisively at the irregular level—conventional forces are required at some point; special forces have a role to play but lack a strategic context —that is, current political and military leaders have no appreciation of their strategic value; and that small wars, non-traditional and asymmetric threats must be taken seriously and co-equally with symmetrical regular conflicts.53 Gray therefore recommends that states should not completely forgo military and strategic preparations for the consequences of Great Power confrontation.

Martin Van Creveld

To return finally to Martin van Creveld, whose critique of contemporary strategic thinking inspired this article and who has authored a number of books about war and strategy, the most notable of which include Supplying War (1977), Command in War (1985), the influential The Transformation of War (1991) and The Sword and the Olive (1998). Although often accused of bias in his commentary on contemporary political issues, his influence on modern strategic theory is without question. Ironically, like Clausewitz, whose present-day relevance he goes to some lengths to discredit, van Creveld leans towards the philosophical: he analyses the nature of war as much as what is required to successfully prosecute it.

The strength of van Creveld’s contribution is his bold and innovative approach to modern strategic issues. He contends that, at a basic level, much of Western contemporary strategic thought is fundamentally flawed, being ‘rooted in a Clausewitzian world picture that is either obsolete or wrong’.54 The underlying reason for this monumental miscalculation is unwillingness or inability on the part of modern and particularly Western strategists to accept that the very nature of war has been transformed from the industrial paradigm of the nineteenth- and early twentieth-centuries. For van Creveld, the large-scale conventional war—warfare as understood by today’s principle military powers—may indeed be in ‘its last gasp.’55 This does not mean that warfare itself is in the decline but rather that it has evolved from what it once was. Accordingly, ‘we are entering an era ... of warfare between ethnic and religious groups [where] even as familiar forms of warfare are sinking into the dustpan of the past, radically new ones are raising their heads ready to take their place.’56 Van Creveld concludes that, as a direct consequence of the transformation of war, modern military force is largely a myth and this is why our ideas about war have stagnated.57

Van Creveld goes to considerable lengths to outline the nature of the threat posed to Western societies from their adversaries in this emerging transformational paradigm of war. He believes that, in an era of nuclear deterrence and globalisation, if people cannot prosecute war between states then they will search, and find, other organisations to fight for.58 Such organisations are likely to be non-state, ideologically motivated and asymmetrically oriented in terms of how they approach the idea of conflict. The problem here is not so much the innate danger of the new threat but the refusal of Western strategists to re-orient themselves to meet it. Van Creveld underlines this claim by suggesting, for example, that ‘brought face to face with terrorism, the largest and mightiest empires the world has ever known have suddenly begun falling into each other’s arms.’59 Further still, the rise of low-intensity conflict may, unless it can be quickly contained, end up destroying the concept of the nation-state entirely.60 The refusal to accept the modern reality of conflict means that the most powerful modern armed forces are largely irrelevant to modern war—indeed, the relevance declines in ‘inverse proportion to their modernity.’61 Unless twenty-first century militaries are willing to adjust both thought and action to the rapidly changing new realities, they are likely to reach the point where they will no longer be capable of effectively employing armed force at all.62

If the weakness of modern Western strategic thought is an inability to accept the transformation of war, then, according to van Creveld, one of the primary causes of this problem is a continuing over-infatuation with Clausewitz’s legacy. Van Creveld’s baseline purpose in writing The Transformation of War was to provide a new, non-Clausewitzian framework for thinking about warfare and strategy.63 Van Creveld’s notion is that while Clausewitz’s model may have described war in the Napoleonic era, it does not represent an accurate picture of modern-day conflict. Clausewitz’s ‘original sin’—and one that plagues strategic thinkers still—is the assumption that ‘war consists of the members of one group killing those of another “in order to” [achieve] this objective or that.’64 He rejects this framework completely by commenting that:

... war does not begin where some people take the lives of others but at the point where they themselves are prepared to risk their own... in other words, a voluntary coping with danger – it is [therefore] the continuation not of politics but of sport.65

Van Creveld criticises Clausewitzian frames of reference for their lack of due regard of the reasons people fight and the power of ideas such as ‘legitimacy’ in modern conflict. For him, unless it considers the things that people fight for, including their motives, no strategic doctrine is or will be effective.66 Van Creveld is especially critical because Clausewitz’s ‘justice’ had nothing to do with strategy and, as a consequence, recommends that ‘in any attempt to rethink strategy, we must start by asking ourselves not how to get the other side to submit to our will but what constitutes a good policy and a just war.’67 It is appropriate for van Creveld himself to describe the long-term consequences for modern strategists and military professionals who continue to retain what he would call an inappropriate Clausewitzian strategic outlook:

[i]t is becoming clearer everyday that this line of reasoning will no longer do. If only we are prepared to look we can see a revolution taking place under our very noses. Just as no Roman citizen was left unaffected by the barbarian invasions, so in vast parts of the world no man, woman or child alive today will be spared the consequences of the newly emerging forms of war... such communities as refuse to look facts in the face and fight for their existence will, in all probability, cease to exist. 68

Conclusion

For however long that there is competition in human affairs, there will be strategy. It is the link between actions and objectives—the plan, means or method by which the former achieves the latter. Strategy and strategy-making are therefore perpetually self-renewing. While the competition in question is war, then there will always be those who devote time and intellectual energy into devising theories that explain its nature and offer insight into what is required for its successful prosecution.

While certainly not the central theme of this article, it is worth spending a moment reflecting on what all of the above means to present-day Australian strategic circumstances. There is no doubt that, if presented with Australian strategic dilemmas, each of the strategists discussed would have valuable individual insights and critiques. The more important point, however, is what their contributions, taken in total, represent. As this article has demonstrated, strategy-making is not dead. Innovation and original thinking mark true advancement in contemporary strategic affairs. Why then is the strategic debate in this country so shallow? Arguments over various items of kit, bouncing back and forth between well-established defence policymakers and analysts—most of whom have past or current ties with the Department of Defence—does not constitute a healthy strategic debate. Postulating various remedies for recruiting shortfalls or retention haemorrhages are not solutions of strategy. Quarrels concerning the utility of an Abrams tank, a Joint Strike Fighter, or a new class of destroyer are not the building blocks of strategy.

These issues are related and important but not the essence of strategy-making. Strategy is about how to use force to achieve policy ends—and we do not discuss this topic nearly enough. If the five theorists discussed were presented with the range of Australian strategic problems they would without doubt each come up with a range of unique perspectives and solutions. The problem is that, in the main, they would have to thrash it out among themselves—there would be few people in this country prepared, qualified or inclined to engage them.

Contrary to van Creveld’s original—and deliberately provocative—contention, the importance and influence of his own ideas, and those of the other strategists discussed, shows that Western strategic thought is not in hiatus or decline. Rather, it progresses and adapts, albeit perhaps at a more measured pace than in some eras past, in response to the often unfamiliar and uncomfortable challenges of modern-day conflict. Most importantly, the strategists discussed have incrementally added to the foundations of strategic thought laid down by the great names of the past, and in some cases are still doing so. In their own way each has questioned the status quo of prevailing thought. Through questioning comes innovation and through innovation comes improvement. While none of the authors discussed may turn out to be Clausewitz’s heir, each is a worthy successor.

Endnotes

1 Martin van Creveld, ‘The End of Strategy?’, Hugh Smith (ed.), The Strategists, Australian Defence Studies Centre, Canberra, 2001, pp. 122–3.

2 In an article of greater length, many other worthy theorists might have been included. The US airpower advocate and architect of strategic paralysis theory, John Warden III, is one such example.

3 Colin S. Gray, Modern Strategy, Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 1 & 17.

4 Carl von Clausewitz, On War, edited and translated by Michael Howard and Peter Paret, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 1976, p. 177; & B.H. Liddell Hart, Strategy: The Indirect Approach, Faber & Faber, London, 1968, p. 334.

5 J. Boone Bartholomees, Jr. (ed.), ‘Chapter 7 – A Survey of Strategic Thought’, US Army War College Guide to National Security Policy and Strategy, U.S. Army War College, Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, 2004, p. 81.

6 Charles C. Krulak, ‘Letter to the Editor’, Inside the Pentagon, 11 March 1997.

7 John Boyd, ‘Strategic Game’, A Discourse on Winning and Losing, Unpublished, August 1987, p. 24, <http://www.d-n-i.net/boyd/pdf/strategy.pdf>.

8 John Boyd, ‘Patterns of Conflict’, A Discourse on Winning and Losing, Unpublished, August 1987, pp. 44 & 128, <http://www.d-n-i.net/boyd/pdf/poc.pdf>.

9 Boyd, ‘Strategic Game’, p. 44.

10 Boyd, ‘Patterns of Conflict’, p. 28.

11 Ibid, p. 101.

12 Ibid, p. 79.

13 Ibid, p. 28.

14 Ibid, p. 116.

15 Ibid, p. 10.

16 Ibid, p. 131.

17 Howard, The Franco-Prussian War: the German Invasion of France, 1870–1871, Rupert Hart-Davis, London, 1968, p. 456.

18 Ibid, p. 454.

19 Ibid, p. 432.

20 Michael Howard, ‘The Forgotten Dimensions of Strategy’, Foreign Affairs, Vol. 57, No. 5, Summer, 1979, p. 975.

21 Ibid, p. 978.

22 Ibid, p. 976.

23 Ibid.

24 Howard, The Franco-Prussian War, p. 455.

25 Howard, ‘The Forgotten Dimensions of Strategy’, pp. 976-77.

26 Ibid, p. 977.

27 Ibid, p. 980.

28 Ibid, p. 977.

29 Ibid, p. 978.

30 Ibid, p. 981.

31 Ibid.

32 Edward Luttwak, Strategy: The Logic of War and Peace, Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, London, 2001, p. xi.

33 Ibid, p. 2.

34 Ibid.

35 Ibid p. 3.

36 Ibid, p. 113.

37 Ibid, p. 114.

38 Ibid.

39 Ibid, p. 4.

40 Ibid, p. 115.

41 Ibid.

42 Ibid, p. 5.

43 Ibid, p. 7.

44 Ibid, p. 8

45 Ibid, pp. 12–13.

46 Colin S. Gray, Modern Strategy, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1999, p. 1.

47 Colin S. Gray, Another Bloody Century: Future Warfare, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 2005, chapter 4, pp. 131–67.

48 Gray, Modern Strategy, p. 129

49 Ibid, p. 130.

50 Gray, Another Bloody Century, p. 13.

51 Gray, Modern Strategy, p. 1.

52 Gray, Another Bloody Century, p. 13.

53 Gray, Modern Strategy, pp. 274–94.

54 Martin van Creveld, The Transformation of War, The Free Press, New York, 1991, p. ix.

55 Such themes have been since picked up by and expanded upon by a number of authors including, most recently, the retired British General Sir Rupert Smith in his book: The Utility of Force: The Art of War in the Modern World, Allen Lane, London, 2005.

56 van Creveld, The Transformation of War, p. ix.

57 Ibid, pp. ix-x.

58 van Creveld, ‘The End of Strategy?’, p. 125.

59 van Creveld, The Transformation of War, p. 192.

60 Ibid.

61 Ibid, p. 32.

62 Ibid, p. ix.

63 Ibid.

64 Ibid, p. 191.

65 Ibid.

66 Ibid, p. 123.

67 van Creveld, ‘The End of Strategy?’, p. 127.

68 van Creveld, The Transformation of War, p. 223.