Abstract

This article examines the generational differences within the Australian Army. The author argues that Generation Y has experienced the Army’s highest operational tempo and that soon they will be able employ the lessons of that experience in command positions. He uses research and observations from generational studies to provide advice to the middle- and senior-level officers currently leading and mentoring this generation. The article concludes that as Australia’s demography shifts, Generation Y will have an increasingly important role to play in the Army’s future.

Introduction

Generational conflict has become the focal point for legions of social theorists and commentators in Australia today. The debate focuses on the emergence of a new younger generation of adults who are entering the workforce with a resounding impact. This new generation has been dubbed the ‘Y Generation’, or ‘Gen Y’ and even fashionably abbreviated to ‘Yers’. Bookstores around the country are now populated with books dedicated to the topic, such as Rebecca Huntley’s The World According to Y, Peter Sheahan’s Understanding the Y Generation, or the more aggressively titled, Please just f**k off it’s our turn now by Ryan Heath. These books have a common aim: to articulate the views of those who belong to Gen Y, and to justify their importance as they move into Australia’s workforce. Each of these writers argues the need for earlier generations to stand up and take notice of Gen Y and all that this younger generation stands for. They espouse a ‘you better watch out’ message for their elders, suggesting that organisations will suffer if the needs of Gen Y are not considered more closely in the future. The books and articles of Gen Y commentators, many of whom belong to that generation or who were born just prior to the generational boundary, go to great lengths to define what it is to be a ‘Yer’ including listing their prevailing strengths and weaknesses. But what they fail to adequately suggest is any strategy that earlier generations can adopt in order to better understand and communicate with Gen Y.1

In the context of the Australian Army, this inter-generational communication translates as providing an answer to the question of how majors and lieutenant colonels can lead the lieutenants and captains of today. The question applies equally to warrant officers who seek to relate to and command the younger sergeants, corporals and privates who are advancing into junior leadership roles. While much has been written on the perceived problems with the Australian Army and the Australian Defence Force’s recruiting and retention strategy, there is a noticeable lack of practical information to equip commanders to communicate more effectively with their Gen Y subordinates.2 This paper seeks to redress this deficiency through definition of the generations in the Army today, exploration of the main behavioural patterns of the emerging Gen Y, and some pointers on how to challenge this young generation so that its full potential can be exploited.

Defining the Generations in the Workplace and the Australian Army Today

In a study of large-scale, trend-based issues such as perceived generational conflict or evolution, it is necessary to make some rather generalised assumptions. This is unavoidable in seeking to make contained and defining descriptions of the generations at play in a society. It is generally agreed that there are three main generations in the workforce, and therefore also in the Australian Army today. I will examine the characteristics of these generations in the following sections.

Baby Boomers

‘Baby Boomers’ comprise the senior generation in the workforce at present. Approximately half the Boomer population is currently in retirement with the rest aged well into their forties. The Boomers are the children of the post-Second World War baby boom, with birthdates from the mid-1940s through to the early 1960s. In the Australian Army the Boomers currently hold senior leadership roles from the rank of general through to colonels and the older lieutenant colonels, as well as warrant officer classes one and two. Baby Boomers have been described as being ‘raised in the “idyllic” 50s, roaming free on their bikes, with little experience of divorce.’3 Later they championed social causes such as feminism, basic human rights and the sexual revolution. They entered a workforce in which jobs were ‘for life’.4 It is primarily their sons and daughters who are entering the workforce today and populating the new Gen Y. Social commentators such as Bernard Salt are quick to point out that, as a result, the Boomer generation is likely to hand the baton of power in organisational management, not to the next generation after them—Gen X—but to the new Gen Y, because they have grown up closer to their image, in the conditions which have been created by the Boomers themselves.

Generation X

Rebecca Huntley describes Gen X as representing an age cohort born between the 1960s and the mid to late 1970s.5 Gen X members are therefore anywhere from 30 years old through to their early forties. In the Australian Army, members of Gen X mostly sit within the ranks of major to lieutenant colonel as officers, and warrant officer class two to senior sergeant within the other ranks. Gen X has been labelled the ‘Me Generation’, by those who see them as too selfish and self-absorbed to commit to a marriage, children, economic planning, or even a permanent job.6 Gen X has also been characterised as ‘deeply pessimistic’, a generation that ‘grew up fearing nuclear annihilation, unemployment and AIDS, with little confidence in the future of the world or [their] own [future].’7 Some commentators have described Gen X as being the ‘thirteenth generation’, as a reflection of the ill-fortune that has dogged this generation, particularly as they began to enter the workplace in the late 1980s during a time of economic recession when they were promised the world, like the generation before them, but eventually forced to fend for themselves.8

As a member of Gen X, Huntley writes, ‘considering Generation Y from the point of view of a Gen-Xer, it is easy to be suspicious, judgmental and even a bit jealous’ because of the seemingly sheltered way that Gen Y has entered the workforce, as opposed to the challenges that Gen X faced.9

Generation Y

Social commentators variously describe members of Gen Y as falling into the age bracket of those who were born from the mid to late 1970s to the very early 1990s. This makes the oldest of the Gen Yers those who are about to turn 30.10 As these figures indicate, Gen Yers have been entering the workplace for almost a dozen years now. In the Australian Army, many are now middle to senior-level captains, or senior corporals to junior sergeants. Gen Yers grew up in an era of uncertainty and complexity, constantly changing technology and mobility. They have adapted to it quickly, capably, and are technologically savvy. According to Huntley, Gen Yers can be characterised as ‘optimistic, idealistic, empowered, ambitious, confident, committed and passionate. They are assured about their own futures and, in many cases, the future of the world.’11 Ryan Heath, (writer and member of Gen Y) describes Gen Yers as ‘global, responsible’ and living ‘24/7 lives’; the ‘most educated, skilled generation yet’; able to multi-task easily, both intensely individual but also keen to work in teams; and ‘not afraid to be contradictory’.12 Writer Don Tapscott describes the key features of Gen Y behaviour as including interactivity based on participation rather than observation; a tolerance of social diversity; a propensity for challenging conventions of authority; and acceptance of economic insecurity and career change as norms.13

Answering the Question of 'Y'

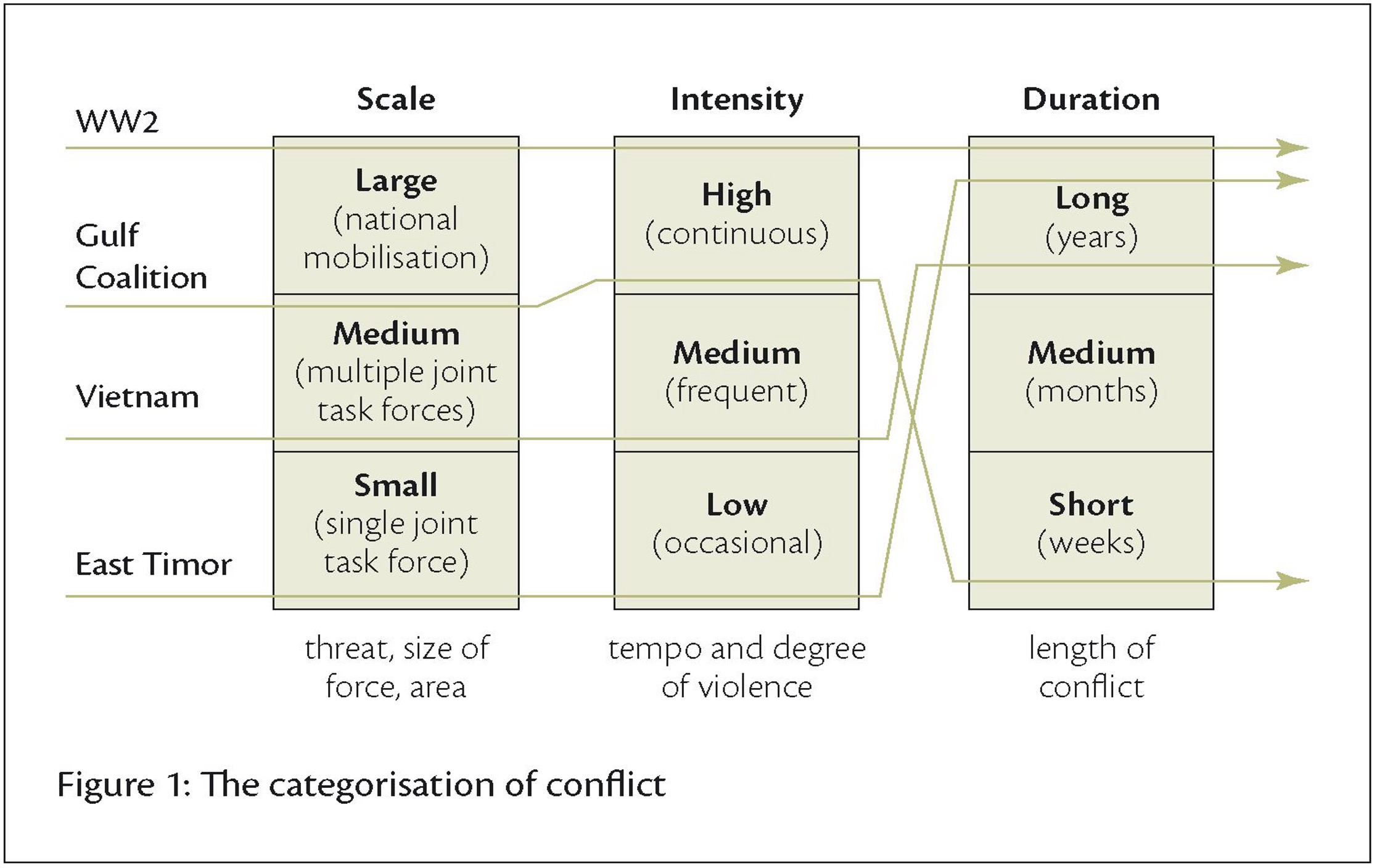

At first glance, it may not be easy to recognise why it is more important than ever before to understand the behavioural traits of this emerging generation known as Gen Y. However, any study of the evolving nature of warfare and its implications for the Australian Army quickly demonstrates why this is so. History has documented the evolution of warfare from large, set-piece battles conducted mostly in a conventional sense, to smaller, more asymmetrical conflicts involving interest groups almost as much as nation-states. The ‘categorisation of conflict’14—illustrated in Figure 1—clearly articulates this point.

Figure 1 maps the fact that today’s conflicts are occurring with less scale and intensity, although they are not always of less duration than their forebears. Another clear indicator of the evolution of warfare lies in the size of Australia’s military commitment to wars and conflicts over the past century or so. The First and Second World Wars saw the mobilisation of Australian forces on a national scale, with divisionalsized forces deployed. In Korea, this was reduced to a brigade commitment and then to a task force for Vietnam. Somalia saw the emergence of a battalion group deployment and, although the commitment to East Timor was larger during the time of the International Force in East Timor, the nucleus of the Australian commitment to the United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor (UNTAET) and later to the Regional Assistance Mission in Solomon Islands (RAMSI) was again battalion group size. More recent operations in the Middle East have seen task groups deployed at more of a company or squadron group level. Smaller, more integrated forces are the norm these days. Warfare today is characterised by what Bruce Berkowitz describes as the ‘four key dynamics’:

There are four key dynamics to the new warfare; asymmetric threats, in which even the strongest armies may suffer from at least one Achilles’ heel; information-technology competition, in which advantages in computers and communication are crucial; the race of decision cycles, in which the first opponent to process and react to information effectively is almost certain to win; and network organization, in which fluid arrays of combat forces can spontaneously organize in multiple ways to fight any given opponent at any time.15

It is Gen Y soldiers and officers who will be called on to lead the Australian Army’s transformation to a more hardened and networked force—the transformation to which they have been committed by the leaders of today. A recent Time Magazine article argued that, ‘guns, tanks and planes were once simple to operate. Now, high-tech communications and weapons systems mean the military needs engineers, electricians and computer technicians just to move.’16 Gen Y is the generation that will take the Australian Army there. This implies that the consequences of getting it wrong and not attracting the right calibre of Gen Y soldiers and officers are far more serious than previously believed. Today, every Australian soldier on operations could make a decision which could become tomorrow’s news in the living rooms throughout Australia or the world. For this very reason, it is critically important that Gen X commanders understand the behavioural traits of their Gen Y subordinates.

Gen Y Caught up in the Now

Gen Yers have grown up with technology. The Internet and mobile phones are second nature to them. In a world in which email and text messaging have overtaken postal mail as the preferred method of communication, Gen Yers are accustomed to having immediate responses. This has resulted in a world which is faster and more connected, and in which Gen Y is leading the way. Yet this is a journey that will be littered with obstacles. In the Army, for example, the art of meticulous staff duties has fallen victim to technology which has imposed instantaneous means of communication such as emails and text messages as the preferred form of documentation. In a fast-paced world, it is inevitable that a greater work output will be required of this younger generation. In creating more work for itself, Gen Y is now provided with a plethora of choice which, while increasing this generation’s situational awareness, has also contradictorily resulted in a lack of strategic foresight amongst many members of Gen Y. Gen X writer Douglas Coupland terms this ‘option paralysis’ amongst Gen Y members who have ‘the tendency, when given unlimited choices to make none.’17

Gen Y Wants to Know Why

Gen Y is a ‘nurtured’ generation. Yers have grown up familiar with parental warnings of ‘stranger danger’ and the importance of maintaining their self-esteem. Their Baby Boomer parents have gone to great lengths to ensure that, in this day of economic uncertainty, their Gen Y children finish school and then go to university. As a result, they are the most highly educated generation to date. A by-product of this feature is that Gen Yers are inquisitive and questioning. Gen Yers do not naturally accept orders unconditionally in the traditional military way. In particular, Yers expect their superiors to listen to their views, particularly when they do not agree with a specific course of action. The reality is that Gen Yers do not function well in hierarchical structures. They are much better suited to organisational structures which are flatter in nature. This is a contradiction that implies a looming clash. The implication is that, in the future, Gen Y soldiers and officers will expect to be given the opportunity to speak to their senior leadership group and voice their concerns on a regular basis. Additionally, they will expect their superiors to listen to and then address their concerns.

The Moral Disposition of Gen Y

Gen Yers have a different set of moral codes from their predecessors. Their world is not black or white but, rather, is full of uncertainties. Gen Yers have been taught that, in life, there are no longer absolute moral truths. One person’s right can quickly be another person’s wrong, and vice versa. As a result, Gen Yers have become more focused on current issues, as these are aspects of life that they can understand and manage. Instead of feeling guilty if they do not develop a plan for the rest of their lives at an early age, Gen Yers tend to be happy to ‘feel’ their way through life, moving between jobs and places far more often than previous generations. In the Australian Army, this does not mean that Gen X leaders should lower their expectations of their Gen Y subordinates. Yers can respond positively and effectively to discipline and, in fact, they thrive on the direction given by their seniors and mentors. In previous generations, the process of making mistakes was considered inexcusable—a view the Australian Army has traditionally reinforced. However, having grown up in a positive and forgiving environment, Gen Yers consider making mistakes a valuable part of the learning process. This behaviour fosters openness and encourages new ideas amongst the members of the generation. A Gen Y subordinate who makes a mistake will expect a Gen X commander to address it immediately through direct feedback which is positive and constructive in nature, as this is the pattern with which most Gen Yers are familiar. Use of the reporting process and the conduct of regular counselling sessions provide the best opportunities for the provision of constructive feedback to Gen Yers.

Gen Y - The Operational Generation

Gen Yers have been described as the ‘operational generation’ as many Yers have joined the Army in the last five or ten years and quickly deployed on operations, unlike many of their X and Boomer leaders who have either missed out entirely, or been on operations in more senior command or staff appointments. That the Australian Army is rich with a generation of ‘twenty-somethings’ who have led sections and platoons in the field in East Timor and other theatres is well documented. They have been in the highly privileged and fortunate position to put into practice what they have been taught in training. Through operational experience they have identified which doctrine works, and modified that which does not. The reality is that this is an opportunity that is rarely afforded junior commanders in a training environment given the constraints of time and money. Gen Y leaders have discovered that they can make an enormous impact on the international stage at a relatively early age. For a generation used to achieving operational outcomes, returning to a highly governed environment and working under older generation leaders who are not used to giving their subordinates such a freedom of movement can be a highly frustrating experience. For some, the answer is to move on to a world that appreciates their skill set—and often expresses this in dollar terms.

How to Lead Gen Y

Given the emerging behavioural traits of Gen Y, it should quickly become apparent that this younger generation could react negatively to poor leadership from Gen X and Boomer commanders who may not fully understand the young soldiers and officers they are leading. Interestingly, the most important solutions to these problems already exist within Australian Army doctrine. For example, the development of a consultative style of leadership within the Army’s mid-level commanders is one of the best ways to overcome discontent amongst subordinate Gen Y leaders. This style of leadership is one that will truly engage Gen Y subordinates in the decision-making process. Dan Fortune reinforces this concept in an article which suggests that individuals of this younger generation prefer a leadership and command style that is based on a ‘decisive transformational methodology’—also referred to as ‘mentoring’.18 He explains: ‘an important feature of mentorship is the role played by a situational style of leadership in which a leader concentrates on harnessing the abilities of his or her followers rather than simply issuing orders’—a truly consultative style of leadership.19 Australian Army doctrine terms this ‘mission command’ and defines it as ‘a system for conducting operations in which subordinates are given a clear indication by a superior of his intentions ... however subordinates are allowed the freedom to decide how to achieve the required result.’20 This approach engenders in Gen Y subordinates an increased trust in the leadership of the Gen X commander. This improved working relationship leads to better performance outcomes for both the individuals and the organisations they lead.

Empowering the Operational Knowledge of Gen Y in a Training Environment

Gen Yers also respond well to instructional roles in a training environment. Employing operationally experienced junior leaders from Gen Y to pass on their valuable knowledge and experience can also be of tremendous benefit to the Army. Better than anyone, Gen Yers know the lessons they were not taught themselves and how this affected them operationally. These are the most valuable lessons for Gen Yers to pass to the Army’s newest soldiers and officers. Gen Y members also have a valuable contribution to make to the development of realistic and relevant doctrine. Posting these young and bright soldiers and officers to training institutions, perhaps with offers of pay incentives and more rapid career advancement, may yet prove the means to retain many of their number. More practically, within the Gen X/Gen Y command relationship, the enduring message from Gen Yers is that subordinates, for all of their strengths and weaknesses, bring to the table a wealth of newly acquired operational experience. For Gen X to overlook, ignore or feel threatened by this would be a mistake. Majors and lieutenant colonels commanding captains and lieutenants with operational experience must provide opportunities for them to be challenged and given a chance to continue to make a difference.21 One option to make best use of the experience of Gen Yers is to entrust them with the responsibility to become package master or subject matter experts within their company or squadron, or even the battalion and regiment to which they have been posted. In an infantry battalion, for example, this would mean giving a particular lieutenant with experience of working with the Security Detachment Iraq the responsibility for creating the Battalion Standing Operating Procedures for the conduct of urban operations at company level. This is a very effective means by which the Gen X commander, sitting above as the company or squadron commander, can assess the quality of a Gen Y subordinate’s work, adopt any valid suggestions and professionally dispute any questionable ones. A key point to remember is that Gen Yers, although keen for responsibility, acknowledge that they do not have all of the answers. More so than their Gen X older cousins, they respect and even crave feedback on their performance and on the direction in which they are heading.

Challenging Generation Y

Understanding Gen Y and more effectively leading them does not mean pandering to their every whim or need, nor does it mean lowering standards. What is essential is to set challenges for the members of this young generation, and then allow them the opportunity to meet those challenges. The best way to lead Gen Yers is to employ the leadership tools which currently exist within the doctrinal concept of ‘mission command’. I have constructed an example based on a typical battalion scenario to illustrate this point.

Officer Commanding Zulu Company - Major White

Major White is a 32-year-old Gen Xer who does not understand generation Y. He has just been posted as the Company Commander, Zulu Company and leads a young company of Gen Y soldiers and junior non-commissioned officers, most of whom have previously served on overseas operational deployments. His closest subordinates are his young lieutenants, all aged in their mid-twenties. As the company prepares for an upcoming training exercise, the platoon commanders develop training packages for their soldiers that include interactive learning, selfpaced modules for slower learners as well as opportunities for section commanders to first develop teamwork amongst their organisations before coming together for platoon and then company-level training. Instead of asking for their input, Major White decides to issue a new company-level training program to replace the platoon-level programs already in place. The program is generic, lacking in detail and imagination. When a concerned lieutenant suggests an improvement based on his own previous operational experience, Major White ignores the substance of the suggestion and chooses to focus instead on the perceived insubordinate nature of his Gen Y lieutenant.

As a result, the morale of the company plunges and their performance suffers. When the company receives a poor report from the training exercise, Major White criticises the commitment of his Gen Y leaders and further limits their responsibilities by choosing to issue his orders directly to his section commanders so that his intent is ‘better understood’ by all. Six months later, one lieutenant has resigned, another has been censured for insubordination, and the third is on the next Special Forces selection course in order to ‘get out of the place’ as quickly as he can. The company has the lowest morale of the battalion and is not selected for any operational deployments. Major White cannot understand why his company is performing so badly. He believes that he is acting in accordance with the leadership models commonly used when he was a lieutenant and which he believed worked well.

Officer Commanding Whisky Company - Major Black

Major Black is the new Company Commander, Whisky Company. He is also 32 years old, but has a better understanding of Gen Y. He also leads a company that includes a number of Gen Y subordinates. When he assumes his appointment, he issues his intent and allows his platoon commanders to develop their programs based around this. He reinforces the use of the Military Appreciation Process and finds that two of his lieutenants carry out their responsibilities effectively, while one fares poorly. When the latter lieutenant makes a bad decision as a result of poor judgement, Major Black corrects the behaviour immediately and issues increased guidance to that individual. When the subordinate continues to make mistakes, Major Black disciplines him further until the behaviour is corrected. At all times Major Black explains why the lieutenant is being disciplined so that he can learn from his mistakes. Meanwhile, the other two subordinates have demonstrated their capability by achieving good results. Major Black now trusts these two subordinates and gives them increased autonomy.

At one planning conference, Major Black issues his guidance, resulting in one of his subordinates, the ill-disciplined one, offering Major Black a suggested improvement to his plan. Major Black decides to modify his plan, producing a more successful outcome for his company. Later, when Major Black’s company is warned out at short notice for a deployment to a regional country in order to help restore law and order, Major Black issues immediate guidance to his subordinates by choosing to brief his entire company on the deployment due to time constraints. Far from feeling left out of the planning process, the lieutenants trust their commander, realising that he has sound reasons for his decision not to consult them this time. They do not complain about this development; they understand it, and carry on preparing their platoons for the deployment. The Battalion Commander has chosen Major Black’s company for the deployment because it was the best performing company in the battalion. When the company returns from deployment, there are two lieutenants due for posting. One of them remains in the battalion and is promoted to the rank of captain where he is able to begin offering his own mentorship to newly arrived lieutenants in his role as the second-in-command of a company. The other is sent to a training institution where he teaches new recruits, while receiving an additional instructor pay allowance.

Examining the Differences in Leadership between Major White and Major Black

This is a practical example—hypothetical in nature and unsubtle in its depiction—which clearly highlights the difference between the leadership styles of the two commanders. That said, the prevailing tenets of these two fictitious leaders do exist within the body of leadership in the Australian Army today. The hope is that the majority of leaders follow in the footsteps of Major Black, who models his leadership style on the principles of ‘mission command’ and, in gaining the trust of his subordinates, does not lose this trust when he is forced to forego consultation due to time constraints. At the same time, as this example demonstrates, when the opportunity arises, Major Black listens to his subordinates and modifies his own plan with a better option that was suggested. Unfortunately however, there are still too many examples of Gen X commanders who follow the example set by Major White, who is unnecessarily autocratic in his leadership and fails to listen to his subordinates or offer them any chance to contribute in a meaningful way. When they try, he interprets this as their questioning his authority and reprimands the subordinates in question. Subsequent poor performance is blamed on the subordinates, which is exacerbated by an even more rigid adherence to an autocratic leadership style, a style that clearly does not produce the best performance from Gen Y.

Conclusion

This article provides Gen X leaders in the Australian Army with broad observations on their Gen Y subordinates so as to assist them to more effectively command their Gen Y juniors. It is clear that this emerging generation is different and does require special attention from its Gen X leaders. Gen Yers have a need for immediate and constant feedback. The ‘nurtured’ status of Gen Y, coupled with the fact that its members have grown up in the age of technology, means that Gen Yers are used to finding their own way by searching for the answers on their own terms. Many have joined the Australian Army during a period of operational intensity and gained invaluable experience which they expect to use and reinvest in the system that trained them by mentoring the generation that follows them. A number of the suggested solutions in this paper are not new. The example of Major White and Major Black demonstrates this point clearly. The need for mentorship and an engagement in the principles of mission command, which includes both consultative leadership as well as the entrustment of Gen Y with a higher degree of responsibility, is now more pressing than ever. The benefit of making the effort far outweighs the impost. Those Gen X leaders who recognise and respond to this need will produce strong and cohesive companies and battalions, squadrons and regiments to further strengthen the Army of tomorrow.

Endnotes

1 Peter Sheahan’s book Generation Y (Hardie Grant Books, Victoria, 2005) does the best job with almost half his book dedicated to sections on managing and retaining Generation Y workers. There is practical advice in his book which earlier generations can use in attempting to become better leaders of Generation Y workers, although such advice still doesn’t neatly fit into a more rigid military environment.

2 An exception is Lieutenant Colonel Dan Fortune’s article, ‘Commanding the Net Generation’, in the Australian Army Journal, December 2003, Vol. 1, No. 2, Land Warfare Studies Centre, Canberra, 2003, pp. 103–10. This article is interesting and thought provoking in the way it offers an alternate approach to leading this young generation. It focuses on introducing management theories of an intuitive nature including discussions of leadership approaches such as mentoring, coaching and 360-degree reporting. The article’s only shortfall is that it focuses on the conceptual but lacks a detailed discussion of more practical aspects which can be given to midlevel commanders in an attempt to better lead their Generation Y subordinates. In all probability, the real value of this article would only be fully realised if a wholesale review of Army’s personnel management system was to occur. For discussion of the issue of retention as it relates to this debate, see Major Colin Lea, ‘Nurturing, Harnessing and Exploiting the Army Officer of the 21st Century’, in the Australian Army Journal, Summer 2005/06, Vol. 3, No. 2, Land Warfare Studies Centre, Canberra, 2005. Major Lea makes the central point that the current structure of career progression for Army officers, in particular its seemingly rigid adherence to ‘minimum time in rank’ requirements for junior to middle-ranking officers, does not favour the retention and advancement of the brightest of the next generation of Army officers.

3 Birrell et.al, NATSEM- Survey of Income and Housing Costs, AMP, HCM Global Pty Ltd, Kanga Batman TAFE, ABS, Australia, 2001.

4 Ibid.

5 Rebecca Huntley, The World According to Y, Allen & Unwin. Sydney, 2006, p. 5.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid., p. 8.

8 Ibid., p. 9.

9 Ibid.

10 Huntley believes that the real power base of Generation Y today is vested in those who are aged in their early to mid-twenties.

11 Ibid., p. 14.

12 Ryan Heath, Please Just F**k off it’s our turn now, Pluto Press, Melbourne, 2006, p. xvii.

13 Don Tapscott, Growing up Digital: The Rise of the Net Generation, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1998, p. 78, quoted in Fortune, ‘Commanding the Net Generation’.

14 Diagram ‘The Categorisation of Conflict’, The Fundamental of Land Warfare, LWDC, Puckapunyal, 2002.

15 Bruce Berkowitz, The New Face of War, The Free Press, New York, 2003.

16 Elizabeth Keenan, ‘The Battle for Bodies’, in Time Pacific Magazine, Time Publications, Sydney, Feb 27 2006.

17 Douglas Coupland, Generation X: Tales for an accelerated culture, St Martin Press, New York, 1997, quoted by Huntley, The World According to Y.

18 Fortune, p. 105.

19 Ibid.

20 The Fundamentals of Land Warfare, p. 16.

21 A larger issue concerns increasing retention of Gen Yers by providing better and more rapid opportunities for advancement within the Army for this young and operational generation. As this issue lies outside the scope of this paper, it will not be given the more detailed consideration it deserves.