Finding Gaps through Littoral Obstacles

Following the Second Marine Division’s seizure of Tarawa in 1943, Colonel Merritt Edson (the divisional chief of staff) wrote that ‘some solution has got to be found to eliminate underwater mines, which I think is the most dangerous thing we have to combat at the moment’.[1] Eighty years later, it remains equally (if not more) difficult to mitigate littoral obstacles.[2] This presents a significant challenge for the Australian Defence Force as it seeks to prepare forces capable of operating in areas defined by the intersection of land and sea. As obstacle technologies become progressively more networked and autonomous, existing obstacle breaching technologies are at risk of becoming at best inefficient and at worst ineffective. Emerging obstacle systems are employing complex sensors and the ability to engage targets at range from offset positions, making breaching a sufficiently wide safe lane ever more difficult. Advances in networked communications, power storage and artificial intelligence (AI) are making the materialisation of self-healing obstacles increasingly likely, further complicating obstacle breaching. To counter these developments, the employment of effective obstacle reconnaissance to find and exploit gaps is becoming ever more important.

While the US’s strategic reconnaissance capabilities were able to find gaps through Japanese obstacles weeks prior to its attack on Tarawa atoll in 1943, emerging obstacle technologies are now decreasing the time available between obstacle reconnaissance and subsequent manoeuvre.[3] Emerging obstacle technologies are increasing the speed, ease, range and accuracy of obstacle emplacement. As a result, although strategic intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance systems (ISR) will continue to help mitigate littoral obstacle threats, future military forces will likely require effective tactical obstacle reconnaissance systems to achieve adequate timeliness, assurance and dispersion. Following Operation Galvanic,[4] an observer suggested that ‘the employment of radio controlled demolition craft for the destruction of underwater obstacles and barbed wire might well prove valuable in preparing a beach for landing’.[5] Just as they did in 1943, modern uncrewed systems present an opportunity to overcome the challenge presented by littoral obstacles, particularly if employed as part of a tactical obstacle reconnaissance system that can find gaps immediately prior to manoeuvre.

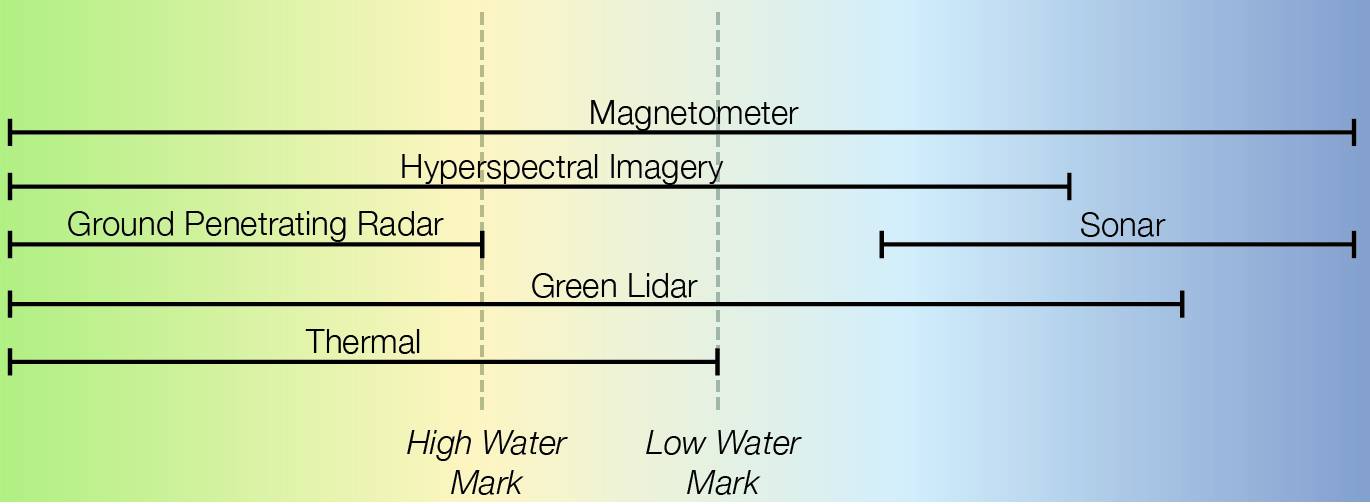

Uncrewed platforms employed as part of a tactical obstacle reconnaissance system are only as effective as the sensors that they carry. Fortunately, sensor technologies are increasing in capability at least as quickly as obstacle systems are increasing in complexity. Magnetometers remain a versatile detection capability on land and underwater, but only against obstacles containing metal. Hyperspectral imagery (HSI) has the potential to be even more effective at detecting littoral obstacles, but only when the significant data storage, processing and communication needs can be met. Ground penetrating radar (GPR) and sonar systems are very effective, especially when they employ synthetic apertures, but are limited to land or underwater use respectively. Light detection and ranging (LiDAR) and thermal sensors are also increasing in utility, particularly when used to supplement other sensors. By combining multiple unmanned platforms, each employing multiple sensors, into a tactical obstacle reconnaissance system, military forces can effectively find and exploit gaps that undermine complex future littoral obstacles.

[1] Merritt Edson to Thomas, ‘Letter to Colonel G.C. Thomas’, 13 December 1943, 8, MSS38133 Merritt Austin Edson Papers, Box 5, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

[2] For an overview of obstacle reconnaissance and breaching at Tarawa, see Matthew Scott, ‘Finding the Gaps: Littoral Obstacles During Operation Galvanic’, Marine Corps History 10, no. 1 (2024): 25–41.

[3] Fifth Amphibious Corps, ‘Report of Gilbert Islands Operation’, 11 January 1944, Enclosure C, COLL 3653 Gilbert Islands Collection, Box 3 ‘Gilberts: 5th Amphibious Corps, Report on Operations, 1944’, Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

[4] Operation Galvanic was the name of the US Fifth Amphibious Force’s operations to seize the Tarawa, Makin and Apamama atolls in 1943.

[5] Richmond Kelly Turner, ‘Extracts from Observer’s Comments on GALVANIC Operation’, 23 December 1943, 23, File Unit ‘COM 5th PHIB FOR’, Series ‘World War II War Diaries, Other Operational Records and Histories’, Record Group 38 ‘Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations’, NARA II.

Technological advances are increasing the threat posed by both explosive and non-explosive obstacles while concurrently increasing opportunities to enhance obstacle effects through observation and fires. The Russo-Ukrainian War offers insights into the current state of landmine technologies and an indication of the growing threats to come. In early 2022, Russian forces began employing ISDM Zemledeliye mine-laying systems to remotely emplace anti-tank (AT) and anti-personnel (AP) minefields.[6] By integrating programmable munitions, meteorological sensors, and fire control systems, the Zemledeliye rapidly emplaces mines while electronically recording and reporting the locations of minefields and lanes.[7] The accuracy and situational awareness delivered by modern systems such as the Zemledeliye allows forces to emplace mines with minimal restriction of their own manoeuvre, thereby reducing barriers to mine employment. Likewise, the increased certainty that minefields will deliver their planned effects allows emplacing forces to delay the establishment of obstacles until the last safe moment, potentially mitigating earlier obstacle reconnaissance. Modern emplacement systems make the establishment of minefields faster, easier, and more reliable—a trend that is likely to persist and that will increase the need for effective tactical-level obstacle reconnaissance.

In addition to demonstrating the growing complexity of mine emplacement systems, the Russo-Ukrainian War highlights the increasing capabilities of landmines themselves. Although many of the minefields emplaced in Ukraine have used traditional munitions (particularly TM-62 series mines), next-generation capabilities are also being employed.[8] Russian forces have emplaced POM-3 AP mines that use seismic sensors to match an approaching target’s signature, then initiate a bounding fragmentation munition with a 16 metre effective range.[9] Modern AT mines have also been employed, including PTKM-1R top-attack mines that can engage targets at up to 100 metres.[10] By engaging targets from offset positions, modern landmines significantly increase the width required to be breached to establish a safe lane. Given the sensor suites, decision-making algorithms, and offset targeting capabilities already employed by these modern mines, it is likely that future minefields will have the kinds of networked self-organising capabilities that the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) envisioned during its mid-2000s Self-Healing Minefield program.[11] Low metal content (LMC) mines will persist but are unlikely to gain significant ‘smart’ capabilities, as doing so would increase their metal content. The employment of modern AP and AT mines in Ukraine suggests that breaching obstacles in the future will be increasingly difficult and that effective obstacle reconnaissance to find bypass options will therefore be increasingly important.

Even though recent conflicts have not featured large-scale employment of sea mines, technological developments have continued to enhance these systems.[12] The increasing availability of unmanned autonomous vehicles will likely enable the emplacement of sea mines immediately before their effects are required, potentially after preliminary obstacle reconnaissance has occurred.[13] Uncrewed vehicle technologies also provide opportunities for low-cost self-deploying mines that could regularly reposition themselves to complicate mine countermeasures.[14] If self-deploying mines are networked, self-healing minefields could counter breaching efforts. In addition to closing gaps, networked autonomous minefields could combine the effects of multiple mines into swarms to destroy high-value targets or to mitigate mine countermeasure systems.[15] Emerging communication technologies, in particular blue-green laser-based optical mesh networks, have the potential to enable communication between mines to be maintained while submerged, limiting exposure to electronic warfare systems.[16] If emerging sea mine systems employ torpedoes or rockets rather than simple blast effects (building on systems such as the Russian PMK-2 and Chinese EM-55 mines), networked minefields will be capable of denying wide avenues of approach.[17] The threat these systems pose is particularly acute for Australia given the prevalence of narrow sea lines within Australia’s primary area of military interest. Like their land-based equivalents, the emerging threats posed by modern sea mines make breaching significantly more difficult, and timely obstacle reconnaissance to find unobstructed routes correspondingly more important.

Technological advances led by the mining and construction industries will likely increase the complexity of future non-explosive obstacles. Intelligent unmanned excavation and earth-moving systems, which could readily be adapted to support military operations, are developing rapidly.[18] At the beginning of 2022, ‘more than 300 intelligent coal mining working faces’ were already operating in China.[19] Although the construction industry is adopting autonomous systems more slowly, ‘many tasks associated with [that] industry fulfil the canonical “dirty, dangerous and dull” criteria of tasks ripe for automation, which leads economists and investors to expect an imminent robotics revolution’.[20] As this revolution occurs, autonomous plant equipment will become more widely available and lower in cost. Technologies that currently enable automated auger and plough systems to mine coal seams could be repurposed to autonomously establish anti-tank ditching. Automated plant equipment could likewise emplace rubble and other non-explosive barriers in urban environments. By executing pre-programmed obstacle emplacement plans and maintaining continuous work, autonomous plant systems would establish obstacles quickly without risking personnel. The potential for non-explosive obstacles to be established at short notice further increases the need for future obstacle reconnaissance to be conducted immediately before planned manoeuvre.

In addition to making modern obstacles increasingly difficult to breach, technological evolution is making the integration of observation and fire with obstacles more pervasive and effective. The proliferation of low-cost uncrewed aerial vehicles (UAVs) and loitering munitions, as well as the digitisation of fire control systems, permits effective observation and fire to cover obstacles far beyond visual or direct fire range.[21] The integration of fires with obstacles can occur at increasing speeds:

[W]here decades ago it may have taken some time for an enemy to detect someone conducting a breach of their obstacles and even longer to bring them under fire, this is now a process that takes a minute or two.[22]

The number of avenues of approach covered by modern land obstacle belts is no longer limited by the need to maintain ground forces in close proximity. Whereas sea mines have often been employed without persistent observation in the past, the ability of modern mines to also act as sensors permits long-range fires to reinforce their effectiveness. As persistent long-range ISR and fires increase the risk inherent in breaching modern obstacles, identifying opportunities to bypass will grow in importance.

[6] Mike Vranic, ‘Ukraine Conflict: Russian Mine-Laying System Makes Combat Debut’, Janes, 30 March 2022.

[7] ‘ISDM Zemledeliye Russian 8x8 Mine-Laying System’, ODIN (website), at: https://odin.tradoc.army.mil/WEG/Asset/ISDM_Zemledeliye_Russian_8x8_Mine-Laying_System (accessed 12 November 2023) ; ‘Rostec Has Fielded the Advanced Zemledeliye Mine-Laying System’, Rostec (website), at: https://rostec.ru/en/news/rostec-has-fielded-the-advanced-zemledeliye-mine-laying-system/ (accessed 12 November 2023).

[8] ‘Background Briefing on Landmine Use in Ukraine’, Human Rights Watch (website), at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/06/15/background-briefing-landmine-use-ukraine

[9] Mick F and NR Jenzen-Jones, ‘Russian POM-3 Anti-Personnel Landmines Documented in Ukraine’, Armament Research Services (website), at: https://armamentresearch.com/russian-pom-3-anti-personnel-landmines-doc… (accessed 12 November 2023); ‘Landmine Use in Ukraine’, Human Rights Watch (website), at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/06/13/landmine-use-ukraine (accessed 12 November 2023); ‘POM-3 (Medallion) Russian Anti-Personnel Mine’, ODIN (website), at: https://odin.tradoc.army.mil/WEG/Asset/POM-3_(Medallion)_Russian_Anti-Personnel_Mine (accessed 12 November 2023).

[10] Human Rights Watch, ‘Landmine Use in Ukraine’; ‘PTKM-1R Russian Anti-Vehicle Mine’, ODIN (website), at: https://odin.tradoc.army.mil/WEG/Asset/PTKM-1R_Russian_Anti-Vehicle_Mine (accessed 12 November 2023).

[11] David A Sparrow, Effectiveness of Small Warheads (Institute for Defense Analyses, 2004).

[12] Both Russia and Ukraine have employed sea mines during the Russo-Ukrainian War, but only at small scale.

[13] Scott Savitz, ‘Emerging Trends in Naval Mining Capabilities’, Maritime Defence Monitor, June 2022, p. 35.

[14] Ibid., p. 36.

[15] Christopher Hevey and Anthony Pollman, ‘Reimagine Offensive Mining: Cooperative, Mobile Mines Will Change the Nature of Mine Warfare’, Proceedings 147, no. 1 (2021): 49.

[16] Ibid.

[17] ‘PMR-2/PMT/PMK‐1/‐2’, Janes, at: https://customer.janes.com/display/JUWS0525-JNW (accessed 1 January 2024); ‘Chinese Sea Mines’, Janes, at: https://customer.janes.com/display/JUWSA321-JNW (accessed 31 December 2023).

[18] Kexue Zhang, Lei Kang, Xuexi Chen, Manchao He, Chun Zu and Dong Li, ‘A Review of Intelligent Unmanned Mining Current Situation and Development Trend’, Energies 15, no. 2 (2022): 1–3.

[19] Ibid., p. 3.

[20] Nathan Melenbrink, Justin Werfel and Achim Menges, ‘On-Site Autonomous Construction Robots: Towards Unsupervised Building’, Automation in Construction 119, no. 3 (2020).

[21] Mick Ryan, ‘Russia is Expanding Its Use of Landmines in Ukraine but Removing Them is Proving Difficult’, ABC, 15 August 2023.

[22] Ibid.

While the technologies that are likely to underpin future obstacle systems continue to increase in capability, so too do technologies that offer an opportunity to mitigate future littoral obstacles. Military, commercial and private investment in unmanned vehicle technologies provides significant opportunities to exploit these platforms as the foundation of tactical obstacle reconnaissance systems. Currently available platforms include UAVs, uncrewed underwater vehicles (UUVs) and uncrewed ground vehicles (UGVs). Of the available options, UAVs offer the greatest level of flexibility as platforms within a tactical obstacle reconnaissance system. Advancements in AI, materials engineering, and battery technologies have allowed UAVs to become cheaper, smaller, more resilient and more autonomous, and to integrate larger numbers of sensors. UAVs provide opportunities to conduct rapid reconnaissance across large areas of interest. Nevertheless, these systems suffer from the greatest payload limitations, are vulnerable to both kinetic and non-kinetic active counter-UAV systems, and can be disrupted by collisions with vegetation or manmade obstacles. Despite these limitations, UAVs offer significant utility as part of a tactical obstacle reconnaissance system.

While UUVs lack the flexibility of aerial systems, their underwater persistence, low signature, and ability to carry large payloads offer distinct advantages during littoral obstacle reconnaissance. Existing UUV systems, including the General Dynamics Bluefin series and the SAAB Double Eagle, have demonstrated the utility of combining multiple sensors to detect underwater obstacles (although reliably detecting buried mines remains a challenge).[23] In comparison to airborne systems, underwater vehicles are less constrained by weight and are, therefore, capable of employing heavier sensor payloads and power systems. UUVs also offer reduced likelihood of detection by terrestrial or airborne sensors when reconnoitring underwater obstacles. The inability to effectively sense obstacles on land is a significant limitation for UUVs, although the impact of this limitation could be reduced by projecting other sensors from the UUV platform (for example, loitering airborne sensors). Although UUVs are less flexible than their airborne equivalents, their underwater persistence offers important opportunities for littoral obstacle reconnaissance.

Like UUVs, UGVs lack the flexibility of flying systems but make up for this shortfall through increased persistence when reconnoitring littoral obstacles on land. The extensive employment of UGVs (for example, the QinetiQ Dragon Runner and TALON systems) during counter-improvised explosive device operations demonstrates the broader potential for ground-based unmanned platforms to conduct obstacle reconnaissance.[24] While UGVs employed in Afghanistan and Iraq were largely tracked or wheeled, quadruped systems such as the Ghost Robotics Vision 60 are becoming increasingly prevalent.[25] In addition to having the potential for greater persistence than airborne platforms, ground-based systems are less susceptible to detection by electromagnetic sensors. The primary limitation of ground-based systems during littoral obstacle reconnaissance is their inability to reconnoitre underwater obstacles. Additionally, UGVs are more susceptible to terrain limitations than UAVs, particularly when attempting to traverse rough or inundated areas. Despite their limitations, the utility of UGVs when reconnoitring land obstacles merits their consideration as part of a wider reconnaissance system. Combining different unmanned vehicle types offers the opportunity to offset their relative strengths and weaknesses to comprehensively reconnoitre littoral environments. The relative strengths and weaknesses of UAVs, UUVs and UGVs are summarised in Table 1.

| Platform | UAV | UUV | UGV |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strengths |

1. Capable of rapid reconnaissance across large areas of interest. 2. Capable of operation above both land and maritime domains. 3. High degree of flexibility. 4. Able to transmit real-time data when not affected by electronic attack.

|

1. Persistence when reconnoitring underwater littoral obstacles. 2. Limited vulnerability to kinetic and non-kinetic attack while submerged. 3. Limited visual and electromagnetic signature while submerged. 4. Less constrained by weight due to buoyancy, and therefore capable of employing heavier sensor payloads and power systems. |

1. Persistence when reconnoitring littoral obstacles on land. 2. Less susceptible to detection by electromagnetic sensors than airborne systems. 3. Able to conduct extended periods of surveillance while remaining stationary to conserve power. 4. Able to transmit real-time data when not affected by electronic attack. |

| Weaknesses |

1. Persistence limited by the power required to stay airborne. 2. Systems prone to catastrophic failure following collisions with vegetation or manmade obstacles. 3. Systems vulnerable to kinetic and non-kinetic attacks, with non-kinetic attacks capable of causing catastrophic crashes. 4. Visual and electromagnetic signatures risk providing adversaries with early warning of planned avenues of approach. 5. Aerodynamic requirements result in a significant trade-off between sensor payloads, platform endurance, and platform size. |

1. Slow rate of movement while submerged compared to airborne systems. 2. Very limited ability to reconnoitre land domain obstacles. 3. Limited ability to transmit real-time data while submerged. |

1. Very limited ability to reconnoitre underwater obstacles. 2. Must be delivered to the beach by airborne or waterborne platforms. 3. Systems vulnerable to kinetic and non-kinetic attack. 4. Visual and electromagnetic signatures risk providing adversaries with early warning of planned avenues of approach. 5. Susceptible to terrain limitations, particularly when attempting to traverse rough or inundated areas. |

While unmanned systems offer suitable platforms to support a future obstacle reconnaissance system, such a system is only as effective as the sensors it employs. Magnetometers, a mainstay of obstacle reconnaissance systems since the Second World War, continue to increase in capability and are likely to remain key sensors regardless of whether UAV, UUV or UGV platforms are employed. By employing transmitting coils to generate eddy currents in metallic substances, these sensors can reliably detect obstacles that contain metal, particularly when paired with AI to interpret collected data.[26] Advancements in atomic magnetometer technology are enabling the development of systems that are smaller, are cheaper, and require less power.[27] Importantly, magnetometers ‘are not significantly affected by soil permittivity’ and can, therefore, detect targets ‘even in high-dielectric moist sand environments’.[28] The primary limitation of magnetometers is their inability to detect non-metallic obstacles.[29] Additionally, magnetometers are susceptible to magnetic interference from the environment, other sensors, and their associated platforms’ structure and power systems.[30] Magnetometers are a proven obstacle detection technology that will remain relevant for tactical obstacle reconnaissance, given that emerging obstacle technologies rely on metal components to enable their ‘smart’ functionality.

Compared to magnetometers, HSI sensors are a much more recent technology that offers opportunities to detect obstacles both on land and underwater when the significant data storage and processing requirements of this technology can be met. HSI systems compare a large number of visible and infrared light wavelength bands ‘with known, uniquely referenced spectral fingerprints’ to detect targets.[31] HSI can detect the spectral signature of LMC mines, as well as the disturbed soil and vegetation caused by burying mines or emplacing non-explosive obstacles.[32] HSI is well suited to UAV employment within the littoral employment given that ‘optical methods are the only means even theoretically capable of [mine] detection through the air-water interface at tactically-useful search rates’.[33] HSI systems can see ‘through the glint and foam clutter on the sea surface’; however, detecting underwater obstacles is only possible ‘where backscattered light from the seafloor has a higher intensity than backscatter from the water column’.[34] Water transparency declines towards the shore due to ‘increased sediment and greater phytoplankton biomass... especially in northern seas between Australia and Indonesia’.[35] The critical disadvantage of HSI systems, however, is the requirement to store and analyse very large amounts of data.[36] HSI can detect a wider range of littoral obstacles than any other type of sensor; however, it can do so only when the captured data can be stored, processed, and communicated.

GPR is another proven obstacle detection technology that offers increasing detection capabilities; however, it can do so only on land. GPR-based systems transmit and receive electromagnetic radiation to detect reflections from metals or from transitions between different dielectric materials.[37] Advancements in synthetic aperture radar (SAR) offer increased detection resolution, exploiting the Doppler frequency shift that results from movement of the sensor over a target to increase the effective size of the radar aperture.[38] SAR-based systems ‘can detect both metallic and dielectric targets’ and can ‘obtain high-resolution underground images’, including during poor weather.[39] GPR can detect buried mines, including ‘plastic landmines down to the smallest size’.[40] GPR is not, however, suitable for detecting obstacles underwater; the microwave band wavelengths employed by radar systems fail to effectively penetrate water. Further, the effectiveness of GPR is limited ‘in soils with high conductivity or high dielectric losses, such as clayey or wet soils, [where] the penetration depth of GPR signals can be significantly reduced’.[41] SAR-based GPR offers significant value as part of a littoral obstacle reconnaissance system; however, it must be paired with other sensors to mitigate threats below the high-water mark.

Sonar systems have a long history of detecting underwater obstacles and will remain a key sensor technology for future obstacle reconnaissance. Sonar systems use underwater sound waves to determine the direction and distance to a target.[42] Advances in synthetic aperture sonar technology are increasing the available resolution of these systems while also enabling smaller arrays to achieve effective detection levels.[43] Sonar can reinforce the effectiveness of other sensors, providing an initial survey of a wide area that allows confirmatory identification by other sensors.[44] Currently, available sonar systems are too heavy to employ from UAVs; however, the development of lightweight dipping sonar systems building on existing sonobuoy technology is underway.[45] Sonar systems are unable to detect obstacles on land and are of limited utility in shallow water, where waves and other environmental noise can generate interference.[46] Further, sonar systems are unable to effectively penetrate through sand and soil, and are therefore unlikely to detect buried underwater mines.[47] As sonar systems gain resolution and reduce in size, their versatility continues to grow; nevertheless, these capabilities must be supplemented with other sensors to complete the landward component of any littoral reconnaissance.

LiDAR presents an opportunity to detect obstacles based on their elevation relative to their surroundings, both on land and underwater. Red LiDAR, also known as terrestrial LiDAR, delivers high measurement accuracy over land and can penetrate through vegetation but cannot effectively penetrate water.[48] Green LiDAR, or bathymetric LiDAR, offers a less common but nevertheless proven alternative that can penetrate water, with ‘recently developed sensors promis[ing] increased spatial resolution (point density) and water depth penetration’.[49] The key disadvantage of green LiDAR, in contrast to red laser systems, is the increased power and data processing demands, which translate into reduced detection resolution. Further, ‘green LiDAR is a more complex and costly technology’.[50] The penetration depth of green lasers is dependent on water clarity; under perfect conditions, penetration to depths beyond 20 metres is possible.[51] By mapping elevation data, LiDAR can detect AT ditches, dragons’ teeth, sea mines, and other obstacles. The key limitation of LiDAR is the risk of false positive detections resulting from relying on elevation data alone. As the resolution available to green LiDAR systems increases, the utility of LiDAR as part of littoral obstacle reconnaissance systems will grow.

Finally, thermal sensors offer a low-cost and small form factor technology that can detect obstacles on land. Thermal sensors achieve detection by analysing a target’s ‘distinct thermal anomaly relative to the surrounding host environment’.[52] Trials employing UAV-mounted thermal cameras have successfully demonstrated an ability to detect surface-laid PFM-1 plastic AP mines.[53] Detection of shallow buried objects is also possible based on ‘the difference of the thermal characteristics between the soil and the buried objects’; however, ‘it is extremely difficult to have a thermal model which is valid under different soil and weather conditions’.[54] Thermal sensors are, however, ineffective against deeply buried obstacles where thermal signatures are ‘masked by the overlaying soil, sediment or vegetation, making thermal differences insignificant’.[55] Nevertheless, thermal sensors remain useful given that most remotely emplaced minefields remain on or near the surface. The key disadvantages of thermal sensors are their very limited ability to detect underwater obstacles and their dependence on weather conditions that generate a sufficient contrast between targets and their surroundings. The relative strengths and weaknesses of available obstacle reconnaissance sensors, including thermal sensors, are summarised in Table 2. Even though thermal sensors can only identify a limited range of obstacles when employed independently, they offer a useful additional data point when used alongside other means of obstacle reconnaissance.

| Sensor | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|

| Magnetometer |

1. Capable of detecting obstacles with metal components both on land and underwater. 2. Not significantly affected by soil permittivity, including wet soil. 3. Capable of detecting buried mines. 4. Miniaturisation of atomic magnetometers allows for small form factor. |

1. Unable to detect obstacles with no metal components. 2. Must be paired with other sensors to continuously adjust for variations in the distance between the sensor and the target to maintain accuracy. 3. Susceptible to environmental interference from nearby ferrous materials and variations in the earth’s magnetic fields. 4. Susceptible to interference from other sensors. 5. Susceptible to interference from platform structures and power systems. 6. Limited detection range. 7. Limited ability to image detected objects. |

| HSI |

1. Capable of detecting the unique spectral signature of obstacles on land and in shallow water. 2. Capable of detecting obstacles with no metal components. 3. Capable of detecting buried mines by identifying disturbed earth and vegetation. 4. Capable of detecting underwater obstacles in shallow water. 5. Capable of detecting non-explosive obstacles such as AT ditches. 6. Can detect obstacles covered by limited flora and fauna. |

1. Requires access to existing spectral data library to effectively classify detected obstacles. 2. Requires significant data processing. 3. Requires significant data storage. 4. Effectiveness is reduced when targets are obscured by terrain or vegetation. 5. Susceptible to deception when relying on disturbed earth and vegetation to detect buried obstacles. 6. Limited ability to identify underwater obstacles in turbid water (for example, near river mouths). 7. Limited detection capability during poor weather. |

| GPR |

1. Capable of detecting obstacles with no metal components. 2. Capable of detecting buried mines. 3. Greater detection range than magnetometers. 4. SAR capable of generating high-resolution underground images. 5. SAR capable of detection during poor weather conditions. |

1. Unable to effectively penetrate water due to microwave band wavelengths. 2. Very limited penetration of wet soil. 3. Susceptible to interference from variations in soil composition and density. 4. Requires a higher level of navigation accuracy than can be provided by global navigation satellite systems (GNSS) alone to compile SAR images. |

| Sonar |

1. Capable of detecting underwater obstacles in deep water. 2. Able to detect non-metal obstacles. 3. Capable of detecting non-explosive obstacles such as underwater barriers. 4. Capable of efficiently searching underwater areas to cue other sensors. |

1. Unable to detect obstacles on land. 2. Limited ability to detect obstacles in shallow water. 3. Unable to detect buried obstacles. 4. Susceptible to interference from other nearby platforms and sonar systems. 5. Synthetic aperture sonar generates large volumes of data that cannot be transmitted while underwater. |

| LiDAR |

1. Capable of detecting the elevation of obstacles relative to their surroundings on land and in shallow water if using green lasers (within the constraints of resolution and penetration depth). 2. Improves the accuracy of other sensors by providing accurate distance to target data. 3. Red LiDAR is capable of penetrating vegetation. 4. Capable of detecting non-explosive obstacles such as AT ditches. |

1. Very limited ability to detect buried mines. 2. Risk of false positive detections resulting from relying on elevation data alone. 3. Requires significant data processing to generate 3D models. 4. Green LiDAR required to penetrate water, which increases power and processing demands. 5. Green LiDAR water penetration depth depends on water clarity at the time of collection. 6. Detection of smaller obstacles requires increased resolution, with corresponding increases in data processing requirements. |

| Thermal |

1. Able to rapidly detect surface laid mines. 2. Capable of detecting non-metallic obstacles. 3. Small form factor. |

1. Negligible ability to detect underwater obstacles. 2. Very limited ability to detect buried mines. 3. Dependent on weather conditions that generate a sufficient temperature differential between targets and their surroundings. 4. Risk of false positive detections resulting from relying on thermal data alone. |

[23] G Sulzberger, J Bono, RJ Manley, T Clem, L Vaizer and R Holtzapple ‘Hunting Sea Mines with UUV-Based Magnetic and Electro-optic Sensors’ OCEANS 2009, MTS/IEEE Biloxi, p. 1; ‘Bluefin-21 Unmanned Underwater Vehicle (UUV)’, General Dynamics Mission Systems (website), at: https://gdmissionsystems.com/products/underwater-vehicles/bluefin-21-autonomous-underwater-vehicle (accessed 20 September 2023); ‘Double Eagle MkII/MkIII PVDS Mine Reconnaissance Vehicle’, SAAB (website), at: https://www.saab.com/contentassets/33ba74f839b44ae3861195862e9d3f97/double-eagle-mkiiii-pvds.pdf (accessed 20 September 2023).

[24] ‘Dragon Runner Small & Compact Robot’, QinetiQ (website), at: https://www.qinetiq.com/en-us/capabilities/ai-analytics-and-advanced-co… (accessed 21 September 2023); ‘TALON® Medium-Sized Tactical Robot’, QinetiQ (website), at: https://www.qinetiq.com/en/what-we-do/services-and-products/talon-mediu… (accessed 21 September 2023).

[25] ’VISION 60’, Ghost Robotics (website), at: https://www.ghostrobotics.io/vision-60 (accessed 21 September 2023).

[26] Y Ganesh, R Raju and R Hegde, ‘Surveillance Drone for Landmine Detection’, 2015 International Conference on Advanced Computing and Communications (ADCOM), Chennai, 18–20 September 2015, p. 34; Sulzberger et al., ‘Hunting Sea Mines with UUV-Based Magnetic and Electro-optic Sensors’, p. 1; Lee-Sun Yoo, Juang-Han Lee, Yong-Kuk Lee, Seom-Kyu Jung and Yosoon Choi, ‘Application of a Drone Magnetometer System to Military Mine Detection in the Demilitarized Zone’, Sensors 21, no. 9 (2021).

[27] Gregory Schultz, Vishal Shah and Jonathan Miller, Applications of Miniaturized Atomic Magnetic Sensors in Military Systems (Hanover: White River Technologies, 2012), p. 4.

[28] Junghan Lee, Haengseon Lee, Sunghyub Ko, Daehyeong Ji and Jongwu Hyeon, ‘Modeling and Implementation of a Joint Airborne Ground Penetrating Radar and Magnetometer System for Landmine Detection’, Remote Sensing 15, no. 15 (2023): 2.

[29] Magnetometers also suffer from a limited effective detection range because the strength of a magnetic field ‘decreases rapidly with the third power of the distance’. Lee et al., ‘Modeling and Implementation’, p. 2.

[30] Systems employing magnetometers must mitigate both the influence of signals from other sensors and the impacts of ‘batteries, drone motors and wires [which] can create strong magnetic interference’. Yoo et al., ‘Application of a Drone Magnetometer System’, pp. 3–6.

[31] HSI can ‘detect difficult targets at the subpixel level, analyze a scene without prior information of the materials to be encountered, distinguish hidden features and camouflage, identify chemical agents in plumes, tag disturbed earth over buried objects, and perform image classification with greatly improved accuracy’. Michal Shimoni, Rob Haelterman and Christiaan Perneel, ‘Hypersectral Imaging for Military and Security Applications: Combining Myriad Processing and Sensing Techniques’, IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Magazine 7, no. 2 (2019): 101–102.

[32] HSI can detect the secondary signs of buried mines, specifically ‘disturbed soil or stressed vegetation as a result of the occluding (i.e., burying) of the device … after the landmine is buried in bare soil, the placement or presence of the device changes the particle size, texture, or moisture of a small region around it’. Shimoni et al., ‘Hypersectral Imaging for Military and Security Applications’, p. 110.

[33] Although underwater obstacles may eventually become covered by flora and fauna, they remain detectable for a significant period of time because of ‘the spectrum of the unique growth naturally selected to adhere to its case (frequently in concentrations and spectral properties that are not typical of the background)’. Michael J DeWeerts, Detection of Underwater Military Munitions by a Synoptic Airborne Multi-Sensor System (Honolulu: BAE Systems Spectral Solutions, 2010), pp. 4–6.

[34] Ibid., pp. 2–7.

[35] Peter Thompson and Karlie McDonald, ‘Water Clarity around Australia—Satellite and In-Situ Observation’, in AJ Richardson, R Eriksen, T Moltmann, I Hodgson-Johnston and JR Wallis (eds), State and Trends of Australia’s Ocean Report (Hobart: CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere, 2020).

[36] Shimoni, et al., ‘Hypersectral Imaging for Military and Security Applications’, p. 102.

[37] GPR will effectively detect targets provided that ‘a backscattered signal is received by the receiving antenna and the amplitude of the bounced signal is above the receivers noise floor’. D Šipoš and D Gleich, ‘A Lightweight and Low-Power UAV-Borne Ground Penetrating Radar Design for Landmine Detection’, Sensors 20, no. 8 (2020): 2.

[38] Xiongsheng Yi and Cailun Huang, ‘Synthetic Aperture Radar Image Speckle Noise Suppression and Mine Target Detection’, Journal of Physics: Conference Series 1650, no. 2 (2020): 1–2.

[39] SAR does, however, require a higher level of navigational accuracy than can be provided by GNSS alone: ‘enabling SAR imaging techniques (i.e. coherent combination of measurements) requires the use of cm- or mm- level accuracy geo-referring and positioning techniques’. María García-Fernández, Yuri Alvarez, Ana Arboleya, Borja Gonzalez-Valdes, Yolanda Rodriguez Vaqueiro, Fernando Las-Heras and Antonio Garcia-Pino, ‘Synthetic Aperture Radar Imaging System for Landmine Detection Using a Ground Penetrating Radar on Board a Unmanned Aerial Vehicle’, IEEE Access 6 (2018): 45100–45102; Yi and Huang, ‘Synthetic Aperture Radar Image Speckle Noise Suppression and Mine Target Detection’, p. 1.

[40] When seeking to detect buried mines on land, GPR ‘currently shows [the] most potential among other technologies, where the main benefit is the ability to detect metal and plastic landmines down to the smallest size’. Šipoš and Gleich, ‘A Lightweight and Low-Power UAV-Borne Ground Penetrating Radar Design for Landmine Detection’, p. 2.

[41]Lee et al., ‘ Modeling and Implementation’, p. 2.

[42] Inyeong Bae and Jungpyo Hong, ‘Survey on the Developments of Unmanned Marine Vehicles: Intelligence and Cooperation’, Sensors 23, no. 10 (2023): 13.

[43] Ibid., p. 13.

[44] Following an initial sonar survey of an area, reconnaissance systems can conduct a ‘confirmatory final classification by reacquiring the target, at close range, with magnetic, acoustic, and electro-optic sensors, and evaluating properties such as geometric details and magnetic moment that can be fused to identify or definitively classify the object’. Sulzberger et al., ‘Hunting Sea Mines with UUV-Based Magnetic and Electro-optic Sensors’, p. 1.

[45] Kamil Sadowski, ‘Hunting Submarines with Drones’, Navy Lookout (website), at: https://www.navylookout.com/hunting-submarines-with-drones/ (accessed 30 December 2023); Alix Valenti, ‘Thales Working on Dipping Sonar Technology for UAVs’, Naval News, at: https://www.navalnews.com/event-news/euronaval-2022/2022/10/thales-working-on-dipping-sonar-technology-for-uavs/ (accessed 30 December 2023).

[46] DeWeerts, Detection of Underwater Military Munitions by a Synoptic Airborne Multi-Sensor System, p. 2.

[47] Ibid.

[48] Leif Kastdalen and Jan Heggenes, Evaluating In-Riverscapes: Remote Sensing Green LiDAR Efficiently Provides Accurate High-Resolution Bathymetric Maps, but Is Limited by Water Penetration (University of South-Eastern Norway, 2023), p. 1.

[49] Ibid.

[50] Raffa Ahmed Osman Ahmed, Knut Alfredsen and Tor Haakon Bakken, Assessment of the Suitability of Green LiDAR in Mapping Lake Bathymetry (Norwegian University of Science and Technology, 2023), p. 4.

[51] The effective depth of green LiDAR has been estimated as between one and three times the ‘Secchi depth’, which is the depth at which a submerged 30 cm white disc is no longer optically visible. Ahmed, Alfredsen and Bakken, Assessment of the Suitability of Green LiDAR, pp. 6–55.

[52] Alex Nikulin, Timothy S De Smet, Jasper Baur, William D Frazer and Jacob C Abramowitz, ‘Detection and Identification of Remnant PFM-1 “Butterfly Mines” with a UAV-Based Thermal-Imaging Protocol’, Remote Sensing 10, no. 11 (2018): 4.

[53] Jasper Baur, Gabriel Steinberg, Alex Nikulin, Kenneth Chiu and Timothy S De Smet, ‘Applying Deep Learning to Automate UAV-Based Detection of Scatterable Landmines’, Remote Sensing 12, no. 5 (2020): 2.

[54] Nguyen Trung Thanh, Hichem Sahli and Dinh Nho Hao, ‘Detection and Characterization of Buried landmines Using Infrared Thermography’, Inverse Problems in Science and Engineering 19, no. 3 (2011): 281–282.

[55] Nikulin, et al., ‘Detection and Identification of Remnant PFM-1 “Butterfly Mines” with a UAV-Based Thermal-Imaging Protocol’, p. 10.

Mitigating the threat of future littoral obstacles requires unmanned platforms and sensors to be combined into a system that can effectively detect all potential obstacles both on land and underwater in a timely manner. Obstacle reconnaissance systems will only be timely and effective if they are employed at a sufficient scale to support subsequent manoeuvre, can move throughout littoral environments, and are capable of processing and communicating the data that their sensors collect. A wide range of platform and sensor combinations could form the basis of an effective system; however, examining a discrete hypothetical scenario allows the broad characteristics of a tactical obstacle reconnaissance system that could overcome future obstacles to be identified. Given the importance of obstacle reconnaissance during the attack on Tarawa in 1943, using that historical case as the basis for a demonstration scenario set in 2043 allows future requirements to be analysed. This demonstration scenario is described in Annex A. The key change to the defences at ‘Future Tarawa’ is that the obstacle systems being employed are networked, can act autonomously, and will be emplaced at the last safe moment. The key capabilities considered during the analysis of the ‘Future Tarawa’ scenario are described in Table 3. Despite the complexity of the threats considered in the 2043 scenario, employing a tactical obstacle reconnaissance system would allow the ability to manoeuvre to be retained.

| LMC landmines | HMC landmines | Sea mines | AT ditches | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tarawa 1943 capabilities |

|

|

|

|

| Baseline current capabilities |

|

|

|

|

| Projected 2043 capabilities |

|

|

|

|

Modelling the potential effectiveness of different platform and sensor combinations against the obstacles employed on ‘Future Tarawa’ suggests that a series of paired UUV and UAV teams would offer a tactical obstacle reconnaissance system that could find the necessary gaps. For the purpose of the ‘Future Tarawa’ scenario, the probability of any platform and sensor combination finding a suitable lane can be estimated by multiplying the probability that a randomly selected lane is clear of obstacles by the probability that the selected platform and sensor combination does not return a false positive or negative report and the probability that the platform will survive the kinetic and non-kinetic threats during the task.

Applying this model through a Monte Carlo simulation as part of a United States Marine Corps School of Advanced Warfighting Future War Project resulted in the outcomes summarised in Table 4. These results suggest that UUV and UAV pairs offer the most efficient obstacle reconnaissance system. Based on the initial modelling, a minimum of 37 pairs of UUV and UAV platforms would be required to find nine lanes for the assault force, equating to 12 pairs per battalion landing team (BLT). Applying a further +/- 25 per cent assumption sensitivity analysis to the UUV and UAV model suggests that between 28 and 60 pairs would be required to find nine suitable lanes, or between nine and 20 pairs per BLT. Despite a wide range of variables determining the real-world placement of different obstacles and the effectiveness of different platforms and sensors, the model’s outcomes reinforce the intuitive value of UUV and UAV combinations for littoral reconnaissance.

| UAV | UAV with dipping sonar | UUV | UUV and UAV | UUV and UGV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Available sensors |

|

|

|

UUV:

UAV:

|

UUV:

UGV:

|

| Probability of finding a suitable lane | 1.3% | 12.4% | 0.06% | 24.6% | 7.4% |

| Platforms required for nine lanes | 703 | 72 | 15,329 \ unworkable | 37 | 122 |

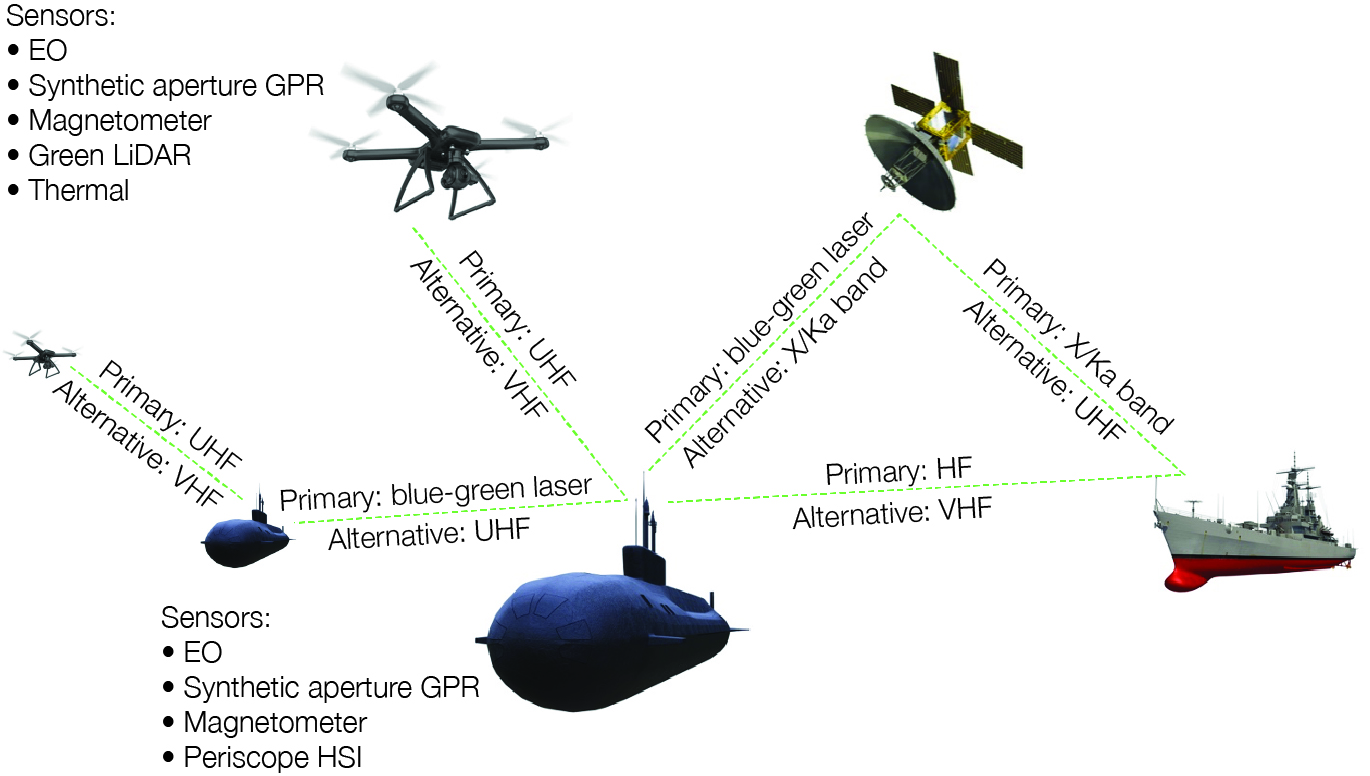

Despite the model employed for the ‘Future Tarawa’ scenario simplifying a wide range of variables that would impact the effectiveness of tactical obstacle reconnaissance systems, the outcomes of the simulation align with qualitative analysis. UUVs are both the most effective platform for reconnoitring underwater obstacles and the platform most efficiently able to carry large data storage and processing payloads. UAVs provide the greatest level of flexibility and can close the gap between the limits of a UUV’s sensors and the land component of the littoral environment. Between the two platforms, magnetometers, sonar, HSI, GPR, green LiDAR, and thermal sensors combine to offer a high probability of detecting obstacles both on land and underwater. Importantly, the overlapping sensor

capabilities of UUV and UAV pairs increases the probability of finding obstacles in the challenging space between the high and low water marks. A potential battle network illustrating a system employing both UUV and UAV capabilities is shown in Figure 2. Combining the strengths of UUV- and UAV-based systems offers the most efficient and effective approach to littoral obstacle reconnaissance.

In addition to the sensors and platforms described in the ‘Future Tarawa’ model, other current and emerging technologies should be integrated as part of a littoral obstacle reconnaissance system. First, AI should be employed to make the reconnaissance system autonomous, thereby mitigating the risk of communication links being disrupted. Second, machine-learning methods such as neural networks should be employed to analyse fused sensor data.[56] Third, navigation data from gyroscopes, Doppler velocity logs, and inertial navigation systems should be shared across networked platforms to increase positioning accuracy, enable the use of synthetic aperture sensors, and mitigate the risks of GNSS disruption.[57] Finally, emerging data transfer technologies such as blue-green laser networks should be employed to ensure that collected data can be shared in an assured and timely manner. When these technologies are employed, the full potential of unmanned platforms and modern sensors can be exploited to undermine the threat of emerging obstacles.

[56] Baur, et al., ‘Applying Deep Learning to Automate UAV-Based Detection of Scatterable Landmines’, p. 3.

[57] Bae and Hong, ‘Survey on the Developments of Unmanned Marine Vehicles’, p. 15.

While effective tactical obstacle systems will be essential to overcome future littoral obstacles, they are only part of the solution. Strategic ISR capabilities (including space, cyber, and electronic warfare systems) are likely to continue to contribute. Advances in machine learning will likely increase the speed and accuracy with which space-based SAR, LiDAR and HSI can be employed to identify obstacles and emplacement systems. Decreasing satellite costs enabled by the global space economy will also likely increase the coverage provided by space-based ISR. Nevertheless, it is unlikely that sufficient satellite persistence will be achieved to prevent an adversary from emplacing obstacles in areas that satellites have previously observed to be clear, particularly when strategic assets are supporting multiple dispersed tactical actions. Instead of finding lanes, remote sensing may cue the employment of tactical reconnaissance systems and enable the suppression of obstacle emplacement systems. While space-based strategic ISR is unlikely to be able to independently mitigate modern obstacle threats, it can increase the efficiency and effectiveness of UUV- and UAV-based systems.

Much like space-based strategic ISR, cyber and electronic warfare capabilities will continue to contribute to future obstacle reconnaissance without being able to offer a standalone solution. Offensive cyber operations and signals intelligence (SIGINT) may identify plans to employ obstacles or may intercept reports of obstacle employment; however, access to this information cannot be assured and therefore cannot provide an independent basis for enabling manoeuvre.[58] Electronic warfare systems may detect communication between components of networked obstacle systems; however, again, the detection of such transmissions cannot be assured. Even if the electronic signatures of future obstacle systems are detected, it remains unlikely that the detailed disposition of obstacle belts would be revealed. Identifying obstacle components in one area does not confirm the absence of obstacles in another; therefore additional obstacle reconnaissance would still be required to find gaps that can be exploited. Like space-based systems, cyber operations and electronic warfare capabilities offer an opportunity to inform the subsequent employment of tactical obstacle reconnaissance capabilities.

Despite the significant detection capabilities that are made possible by combining multiple platforms and sensors, reconnaissance systems cannot find gaps that do not exist. The ability to breach obstacles therefore remains essential. Likewise, the ability to breach obstacles reduces deliberately offer gaps that shape a force into preferred engagement areas. Given the complexity presented by future obstacle systems, breaching operations will require significant and likely disproportionate resource expenditure. Large numbers of remotely delivered munitions are likely to be necessary to achieve sufficiently wide lanes. The procurement and sustainment challenges presented by this munition requirement can be reduced by repurposing general-purpose ordnance, an approach reflected in the US decision to shift from bespoke dart-based munitions to existing MK-80 series bombs as part of the Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM) Assault Breaching System (JABS).[59] Unmanned systems, including loitering munitions, offer further alternatives; however, the size of required breaching munitions will remain inversely related to the accuracy with which they can be delivered. When breaching becomes the only option, tactical obstacle reconnaissance systems still have a role to play, providing targeting data to support breaching fires. Tactical reconnaissance systems also have a role on post-breaching surveillance—monitoring avenues of approach to ensure that further obstacles are not emplaced. Nevertheless, breaching should remain an option of last resort.

[58] Prior to the seizure of Tarawa in 1943, ULTRA SIGINT intercepts provided information about Japanese troop movements and logistical requests which enabled intelligence staff to assess the likely strength of the defences. Although these intercepts could give an indication of the scale of the likely obstacles, it could not confirm how those obstacles were arrayed. Joseph H Alexander, Utmost Savagery: The Three Days of Tarawa (Annapolis MD: Naval Institute Press, 1995), p. 59.

[59] ‘CMS—Countermine System’, United States Navy (website), at: https://www.navy.mil/Resources/Fact-Files/Display-FactFiles/Article/2166814/cms-countermine-system/ (accessed 7 January 2024); Department of Defense, PE 0604126N: (U)Littoral Airborne MCM (Washington DC, 2019).

When the Second Marine Division landed at Tarawa in 1943, strategic reconnaissance was sufficient to find gaps through the Japanese obstacles. Submarines, long-range aircraft, signals intelligence, and former residents of the target islands were able to provide sufficient information about obstacle dispositions before the Fifth Amphibious Force closed with its objectives. Minesweepers and dismounted combat engineers were able to reduce the residual risks. While effective at the time, the approach taken by the US in World War II would be unlikely to succeed today and is even less likely to be effective in the future. Instead, commanders must execute tactical obstacle reconnaissance immediately prior to manoeuvre. As littoral obstacles become increasingly networked, autonomous and able to engage targets at extended ranges, breaching lanes will become progressively more difficult. Finding lanes to bypass obstacles is, therefore, critical to tactical success.

Teams of UUVs and UAVs will likely offer the most effective and efficient means of conducting tactical obstacle reconnaissance during the next two decades. Using these platforms to employ a combination of magnetometers, HSI, GPR, sonar, LiDAR, and thermal sensors would enable obstacles to be found with a high degree of assurance. Other emerging sensor technologies—for example, those employing nuclear quadrupole resonance—may further increase accuracy in the long term but are not necessary to begin developing and fielding workable systems.[60] Likewise, improved data storage and processing technologies will eventually enable HSI to be processed on board small UAVs; however, effective obstacle reconnaissance is achievable without waiting for those capabilities to become available. While reconnaissance technologies are likely to continue improving, so are the technologies employed by obstacle systems. Ongoing investment in obstacle reconnaissance is therefore necessary not only to meet the future challenge but to stay ahead of it. Breaching should remain an option of last resort; however, tactical obstacle reconnaissance systems offer opportunities to enhance breaching efficiency when required. Employing teams of multi-sensor unmanned platforms to find and exploit gaps remains the best way to mitigate future littoral obstacles.

An earlier version of this paper was submitted as part of the Marine Corps University Master of Operational Studies program. The author would like to thank Dr Michael Morris for his mentorship during the writing of the original paper.

[60] García-Fernández, et al.,‘Synthetic Aperture Radar Imaging System for Landmine Detection’, p. 45101; Schultz, Shah and Miller, Applications of Miniaturized Atomic Magnetic Sensors in Military Systems, p. 2.

The ‘Battle for Future Tarawa’ is a hypothetical scenario that unfolds in 2043 amid a global conflict between the United States and Olvana,[62] a culmination of escalating tensions over several decades. The roots of this conflict trace back to the early 21st century, marked by competitive advancements in technology, economic rivalry, and geopolitical posturing. The South China Sea disputes, trade wars and cyber espionage had laid the groundwork for this confrontation. As Olvana expanded its influence across the Asia-Pacific region, the US sought to counterbalance this through strategic partnerships and military presence, leading to an inevitable clash of interests. The conflict was further fuelled by a race for technological supremacy, particularly in AI and autonomous systems, setting the stage for a new era of warfare. As the global order frayed under the strain of these tensions, smaller nations were drawn into the vortex, with key strategic locations becoming flashpoints, one of which was the island of Tarawa.

In the context of the global war, Tarawa emerged as a critical strategic point. For Olvana, it serves as a forward outpost in the Pacific, enabling projection of power and control over crucial sea lanes. Its transformation into a technologically fortified stronghold was a clear demonstration of Olvana’s military capabilities and resolve. From the US perspective, Tarawa represents a significant obstacle to maintaining freedom of navigation and influence in the Pacific. Its recapture is vital for the US to assert its presence and to counter Olvana’s expansion. For both nations, Tarawa is not just a piece of land; it is a symbol of power and control in a region that has become the centre of global strategic competition. The US aims to dismantle the Olvanan stronghold, while Olvana aims to showcase its technological and military prowess, making Tarawa a pivotal battleground in the wider conflict.

Olvana’s defence strategy for Tarawa is shaped by several key trends. Technologically, advancements in AI, machine learning and autonomous systems are at the forefront. Politically, Olvana’s assertiveness in the Pacific is part of its broader strategy to challenge US dominance and establish itself as a global power. The use of autonomous defence systems at Tarawa is a testament to Olvana’s commitment to leveraging cutting-edge technology in warfare. The Olvanan military doctrine has evolved to integrate these technologies, focusing on creating impenetrable defences using AI-driven assets. This approach is also influenced by a desire to minimise personnel on the frontline, thereby reducing human casualties while maximising defensive capabilities. Economically, Olvana’s investment in these technologies is seen as a means to showcase its industrial and technological advancement on the global stage, furthering its strategic interests.

Olvana’s defensive fortifications on Tarawa centre around an advanced network of smart mines and autonomous equipment. The smart mines, both on land and in the surrounding sea, are equipped with AI and machine-learning capabilities, enabling them to communicate and coordinate responses to perceived threats. This network can adapt its strategy in real time, repositioning mines and altering tactics based on the evolving battlefield situation. The mines are designed to be highly effective against both personnel and vehicles, posing a significant challenge to any invading force. On the island itself, Olvana deployed autonomous excavation equipment, which can continuously fortify defences, repair damage and create new strategic positions. This machinery operates under the guidance of the central AI network, ensuring a relentless and adaptive defensive posture, making Tarawa a formidable fortress against any assault.

The US forces face multifaceted challenges in their attempt to overcome the Olvanan defences at Tarawa. First, the technological prowess of the AI-driven mine network presents a unique and unprecedented obstacle. The mines’ ability to communicate and adapt makes a conventional assault highly risky. Second, electronic and cyber warfare capabilities are critical to disrupting the Olvanan AI network, requiring advanced technological tools and expertise. The efficacy of these operations is uncertain against a sophisticated and potentially self-healing AI system. Third, the political implications of a direct assault are complex, with the risk of escalation and wider regional consequences. This requires careful strategic planning and consideration of international diplomatic repercussions. Last, the US must balance the need for a decisive victory with the ethical considerations of engaging in a battlefield dominated by autonomous systems, navigating the moral complexities of modern warfare.

Recognising that the risks posed by Olvana’s occupation of Tarawa could no longer be tolerated, not least the risk of long-range fires striking critical platforms in Guam and Hawaii, the US decides to again seize Tarawa. Given that the Olvanan fortifications at Tarawa would likely mitigate the effects of long-range fires, the US accepts that ground forces will need to secure the island following a joint forcible entry operation. Strategic ISR assets reveal valuable details about the Olvanan obstacle plan that support detailed planning for the assault. Offensive cyber operations reveal Olvanan logistical preparations for the defence of Tarawa, indicating that 3,000 mines have been delivered to the atoll. This includes networked sea and landmines that are capable of ‘self-healing’, as well as difficult-to-detect low metal content mines. Space-based IMINT identifies the locations of a number of sea mines; however these randomly reposition between satellite passes. Landmine locations are not detected, suggesting that these munitions are not yet emplaced. Finally, submarine-based SIGINT identifies that unmanned plant equipment is communicating with a control station on the island. While strategic ISR had proven invaluable, it has been unable to confirm or deny the location of safe lanes on Tarawa.

As the landing force approaches Tarawa, fires from air, surface and subsurface platforms begin kinetically and electronically suppressing the Olvanan defences. Importantly, this suppression includes efforts to suppress obstacle emplacement systems and to disrupt communication between already emplaced obstacles. Concurrently, offensive cyber operations degrade the ability of Olvanan satellites to communicate with submerged mines. Nevertheless, many of the landmines are successfully emplaced while most of the sea mines remain active. Plant equipment establishing anti-tank ditches is destroyed, but not before a number of planned ditches are completed. While suppression continues, the assault force deploys pairs of UUVs and UAVs, which together commence tactical obstacle reconnaissance. Together, the paired UUV and UAV systems carry sufficient sensors to effectively detect obstacles throughout the littoral environment. Although Olvanan electronic attack periodically disrupts UAV communication, sufficient data is transmitted from UAV to UUV platforms to enable the reconnaissance tasks to be completed. In turn, the UUVs compile and process the available data, transmitting the locations of both obstacles and identified safe lanes back to the assault force.

While the assault force aspired to find nine safe lanes on Tarawa, the combined effects of obstacle density and reconnaissance platform attrition resulted in only six lanes being found. Nevertheless, the data transmitted by the tactical reconnaissance enables the assault force to breach the remaining lanes. Breaching munitions fired from airborne and seaborne platforms target mines on land and in shallow water while collapsing ditches and other non-explosive obstacles. Sea mines in deeper water are breached by dedicated unmanned underwater vessels. While the breaching munitions were fused to minimise cratering, broken ground was inevitable. Nevertheless, the tracked amphibious vehicles employed by the assault force maintained the necessary mobility. As the assault force passes through its assigned lanes, mechanical breaching and active protection systems shield the vehicles from residual protective obstacles. As the assault force moves underground through the Olvanan fortifications, dismounted manual and explosive assault breaching techniques are employed to reduce the final defences and secure Tarawa. While strategic ISR and obstacle breaching capabilities contributed to the success of the operation, tactical obstacle reconnaissance proved essential to overcoming the Olvanan defence.

[61] Elements of this scenario were generated by OpenAI’s ChatGPT-4 model.

[62] ‘Olvana Country Overview’, Decisive Action Training Environment (website), at: https://date.army.gov.au/operating-environments/indo-pacific/olvana (accessed 29 February 2024).