Looking back at the Malayan campaign of 1941–42 from the distance of more than sixty years, what is most striking is how quickly the Japanese invaders triumphed. In large measure it was a triumph of command. The Japanese commander of the XXVth Army, General Tomoyuki Yamashita, had assumed command only in November 1941, a few weeks before the invasion. He inherited someone else’s plan and put it into action with stunning effect. In seventy days Yamashita’s forces advanced the length of Malaya, destroying a number of British Empire brigades in the process, and captured Singapore on 15 February 1942.

Yamashita’s principal opponent for most of this time was the General Officer Commanding (GOC) Malaya Command, Lieutenant General A. E. Percival. The latter has gone down as probably the most unfortunate figure of the campaign. 1 It is important to note, however, that Percival was never in overall command and, over a period of two months, he witnessed a bewildering series of Commanders-in-Chief Far East come and go, including Brooke-Popham, Pownall and Wavell. Yet, ultimately, it was Percival who ‘carried the can’ for the cumulative mistakes of the British commanders. Indeed, of all the images to come out of the melancholy Malaya campaign, the photograph of Percival and his group of British surrenderers—with their white knobbly knees and Bombay bloomers, marching ignominiously towards the Ford Factory under a white flag to meet the victorious Yamashita—is the most abiding. Unlike Percival, Bennett escaped from Singapore, having told his troops not to escape but to stand fast. Returning to Australia, he was ‘kicked upstairs’ and promoted to the rank of lieutenant general. However, he was posted to Western Australia and was never again given an active command during the war. 2

In his book Singapore: The Chain of Disaster, Major General S. Woodburn Kirby, the British Official Historian of the war against Japan, argues that the blame for defeat in Malaya–Singapore must be placed squarely on the shoulders of successive British governments. It was British government decisions from as early as 1919 that built up a chain of errors leading inevitably to disaster. 3 Woodburn Kirby believes that the British made major errors in the military conduct of their campaign. He also contends that, by early 1942, nothing could have been done to save the Singapore garrison.

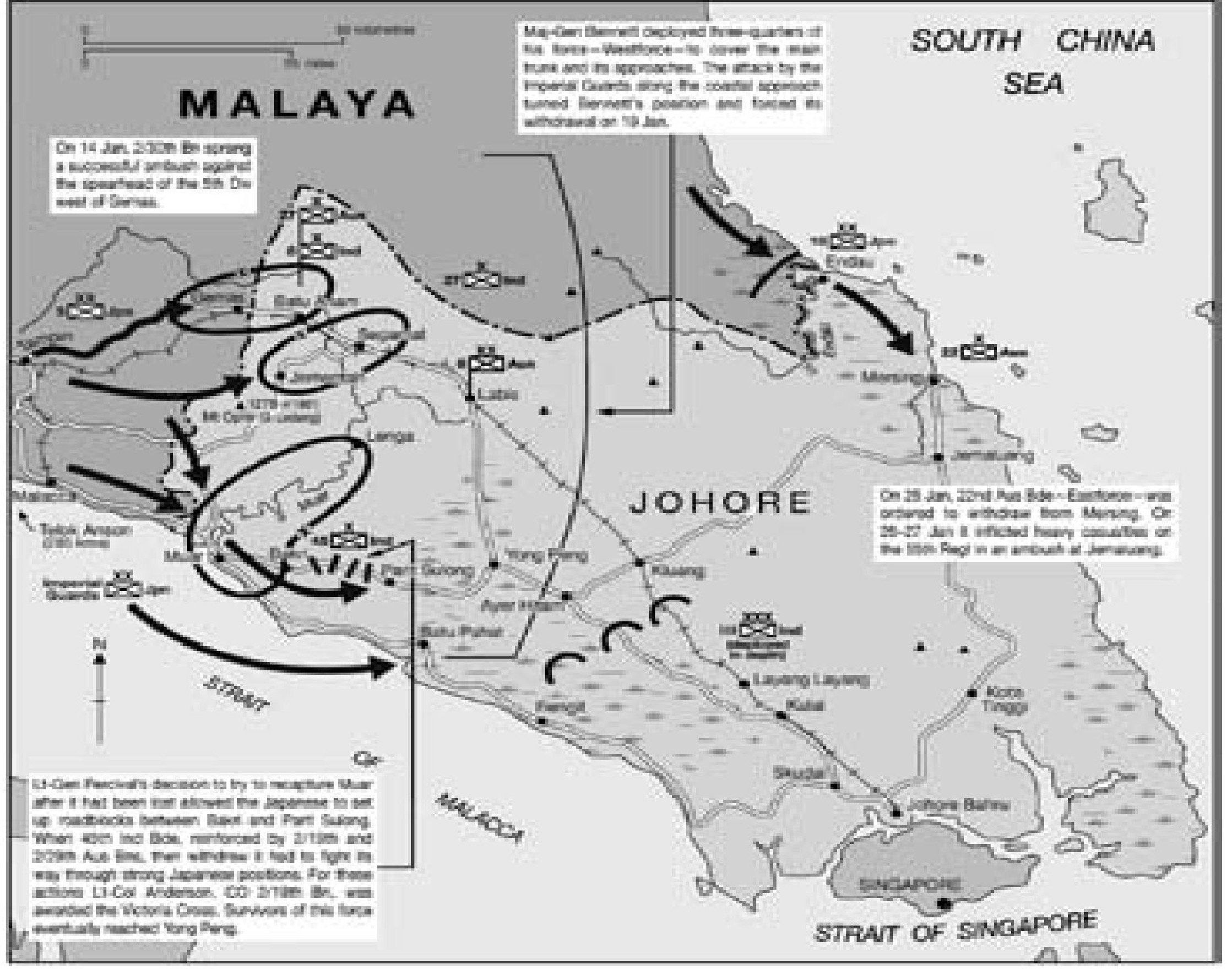

It is the conduct of the Malayan campaign with which this essay is mainly concerned. In particular, it seeks to examine the decisions taken at key points by two of the principal figures on the British side, Percival himself and Major-General H. G. Bennett, commanding the Australian Imperial Force, including the 8th Australian Division. The article analyses the attempt by Percival and Bennett to hold, in virtual isolation, a piece of coast and river from the mouth of the Muar River to a point 40 km inland with a single, inexperienced Indian brigade in riverine and swamp country. The Muar was a considerable obstacle whose tactical value was squandered during the fighting.

The Fall of Malaya: The Strategic Background

In terms of strategy, there is strong evidence to suggest that, after becoming Prime Minister in May 1940, Winston Churchill was extremely reluctant to look farther east than India in matters of Empire and Commonwealth defence. Field Marshal Dill, Chief of the Imperial General Staff, almost resigned over the issue of the relative priority of the Middle Eastern and Far Eastern theatres of operations.

Churchill was proven consistently wrong in his threat assessment of Japan. He had long believed that the Japanese were no match for Western nations. For example, in 1938, he had confidently asserted that the Japanese would never dare to confront the English-speaking nations militarily, because the latter could wage war ‘at a level at which it would be quite impossible for Japan to compete’. Churchill did not change his views once in power. In 1941, he declared that the Japanese would ‘fold up like the Italians’ and went on to describe them as ‘the wops of the Far East’. 4

What bothered even Churchill’s most loyal supporters was that even material support for the Soviet Union appeared to have greater priority in British strategic planning than the defence of Malaya, Burma and Australasia.5 At a time when Percival in Malaya was clamouring for further reinforcements of infantry, and particularly of armour, Churchill went so far as to contemplate the use of the 18th and 50th divisions serving on Russia’s southern front. In the event, several hundred tanks and ten squadrons of front-line aircraft were given as gifts to the Soviet Union. 6 Churchill’s approach to the defence of the Far East reinforced a belief that his policy was to appease, rather than confront, Imperial Japan. As a result, British forces deployed to Malaya, while being more than token, were not realistic.

British Underestimation of the Japanese

Like Churchill, the British command in Malaya did not have a realistic understanding of the abilities of the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy. The ‘Japanophiles’, who sought an objective analysis of Japan’s strengths, were outnumbered by the ‘old China hands’, whose views on Japan were unalterably ethnocentric. The ‘Japanophiles’ took care to assess Japanese military proficiency objectively and against a template of Western criteria. 7 Contrary observations that stressed Japanese military inferiority came generally from the school of ‘old China hands’, and the latter’s prejudices remained more prevalent among the local British military staffs in places such as Singapore, Burma and Hong Kong.

Colonel G. T. Wards, the ‘Japanophile’ British Military Attaché in Tokyo, gave the then GOC, Major General J. E. Bond, and the Singapore garrison an illustration of the menace that the Japanese armed forces represented. On a visit to Singapore, Wards told his audience that he had participated in Japanese ground-force manoeuvres and exercises both in Japan and in China. He warned his colleagues that the Japanese Army was ‘a first-class fighting machine’ and emphasised the extreme physical fitness of the Japanese troops, their fanatical patriotism, marching prowess and the efficiency of both unit and sub-unit commanders. The Military Attache also noted the professionalism of the Japanese General Staff, including its ability to handle large formations of troops over immense distances.

Wards punctured a number of British myths about the Japanese. These myths included a belief in Singapore military circles that the Japanese forces never operated by night and that they were poor mechanics, drivers and pilots. Wards pointed out the Japanese military’s immense talent for secrecy, surprise and deception. Japanese commanders knew infinitely more about the British Empire forces in Malaya than senior British officers knew about Japan’s armed forces.

However, Wards’s valuable advice did not receive proper attention in Singapore’s military circles. 8 This situation occurred despite the fact that Wards’s observations were supported by two 1940 War Office military pamphlets on the Japanese armed forces. 9 The atmosphere of self-deception among senior officers in Malaya remained palpable right up until the outbreak of hostilities in 1941. One of Brooke-Popham’s officers in Singapore told an arriving Australian officer that ‘the Japanese Army is a bubble waiting to be pricked’.

Indeed, summing up Wards’s 1941 talk, Major General Bond told his assembled officers that the Military Attache’s statements were unnecessarily alarmist and were far from the truth, and that superior intelligence kept the British apprised of every Japanese move. The last claim was untrue. The four-digit, mainline Japanese Army code was not penetrated on a systematic basis until troops of the 9th Australian Division captured the Japanese 20th Division’s entire cipher library at Sio in New Guinea in January 1944. 10

Although neither Percival nor Bennett was in Malaya at the time of Wards’s visit in 1940, it is uncanny that neither officer chose to challenge Bond’s views. Even as his forces were bundled back onto Singapore Island, Percival elected throughout the campaign to adhere to English public-school ‘good form’ by refusing to alarm the local population. For his part, Bennett, in his first instruction to his command in Malaya, suggested that the Japanese lacked the ‘jungle mindedness’ that he intended to instil in his own troops. As Bennett put it:

Our enemy will not be so trained [in jungle warfare and] is unaccustomed to any surprise attack and reacts badly to it. Generally speaking he is weak in small unit training, and the initiative of his small units is of a low standard. 11

Similarly, a Malaya Command Training Instruction of the same period stated that the Japanese soldier was ‘peculiarly helpless against unforeseen action by his enemy’.12 The belief that Bennett was a rigorous trainer of troops in the Malayan jungle persisted long after the end of the war. In 1962, as a young officer, the author studied Colonel E. G. Keogh’s potted history of the Malayan campaign. Keogh concluded by stating that:

General Bennett has become a controversial figure. But on one point there is no room for controversy—he trained his troops thoroughly. If Percival had caused his other subordinates to train their troops as hard and as well as Bennett trained his, the story of Malaya might well be very different. 13

In fact, nothing could have been farther from the truth. 14 Bennett did not supervise the training of troops, almost never went into the jungle himself and, as his own diary makes clear, was overwhelmingly concerned with what he perceived as his personal destiny to move to the upper echelons of the Australian Army. 15 Bennett’s almost total preoccupation with self-interest is revealed in a letter to Frank Forde, the Minister for the Army, on 27 January 1942. With the Japanese closing rapidly on the Straits of Johore, Bennett wrote:

When the war commenced, I was senior to both Blamey and Lavarack and was superseded, not on account of inefficiency, but merely because of jealousy. Also, certain people wanted to see a permanent soldier and not a citizen soldier at the head. If you bring anyone else here to command the Australian Corps when it arrives [sic], I will ask to be relieved. I will take it as a note of lack of confidence in me. I was a Major General when Lavarack was a Lieutenant Colonel.

Both troops and staff had to look elsewhere for inspiration to men such as Colonel J. H. Thyer, Bennett’s General Staff Officer Grade 1 (Operations) and to Taylor, the commander of the 22nd Brigade, in order to try to discern their real military task in Malaya.

In turn, an overconfident cynicism, which was natural to Bennett, probably accounted for his own low assessment of the potential Japanese enemy. 16 A considerable inertia pervaded Malaya Command’s estimates of Japanese military capability. Even an effective GOC, Malaya—such as Major General Dobbie, himself an eyewitness of Imperial Japanese Army manoeuvres in 1936—retained a qualified view of the effectiveness of the Japanese Army. It would be surprising if the then Colonel A. E. Percival, Dobbie’s Chief of Staff in Singapore, differed from that assessment.

Yet, as the Allies subsequently found to their cost, the Japanese Army in 1941 was vastly different from what it had been half a decade earlier. Percival was only one among many senior officers whose judgments had not moved with the times. Indeed, when General Wavell—the newly appointed Supreme Commander ABDA (American, British, Dutch, Australian) Command— visited Singapore on 7–8 January 1942, he was appalled to find that no effort had then been made to defend Singapore Island, except for the establishment of the prewar naval guns. Percival admitted that he had not undertaken defensive measures because he believed that ‘building defences was bad for morale’.

The Defence of Northern Johore

The defence of the Muar River should have been the main line of resistance in Northern Johore. An altercation that occurred between Bennett and Thyer helps to put into perspective Bennett’s low estimate of the likelihood that the Japanese would use the west coast route as a major thrust line. On 1–2 January, a Japanese force was moved down the west coast by boat to points west and south-west of Telok Anson, and deployed behind the British defence line. The combined strength of the Japanese was over four battalions, and there was little doubt that they would use the stratagem again if circumstances permitted.

As his diary reveals, Bennett was aware of Japanese movements. Yet, when Thyer suggested to Bennett that the Japanese might employ similar tactics in the east, the former’s advice was met with an illogical rebuke:

There are still signs of [a] lack of [a] sense of proportion in Thyer who has passed it on to his staff. He worries interminably about remotely possible hair brain schemes the enemy might adopt but ignores completely the big problem. He has on his brain a likelihood that the enemy will come up [the] Pahang or Rompin rivers by large boat—then by light craft then by foot over 50 miles of jungle. Why should he? 17

Since the Japanese Imperial Guards Division was about to use a similar scheme of manoeuvre against the 45th Brigade’s position on the Muar, Bennett might have profited from listening to Thyer. Instead Bennett remained obdurate and, in any case, matters had become more complex because Wavell insisted on a complete change in the plan for the defence of Johore.

In his original plan, Percival had allotted the defence of the key north-western area of Johore to Lieutenant General Lewis Heath’s 3rd Indian Corps, with Bennett commanding in the east of the state. On 8 January 1941, Wavell realised that the loss of Johore would almost certainly mean the loss of Singapore. As a result, the ABDA Commander insisted that the plan be changed and decided that Bennett showed greater fighting spirit than either Percival or Heath. Consequently, Wavell resolved to entrust the main defence of Johore to Bennett. However, in doing so, the ABDA Commander failed to detect the flaws in Bennett’s character and did not recognise the deep dissent in the latter’s division. Heath was ordered into a reserve position behind Bennett’s force and, to add to the complicated nature of the British defence dispositions, took Bennett’s 22nd Brigade under his command.

Wavell’s tactical interference undercut Percival’s already-diminishing authority and was damaging. For instance, the division of the defence of Johore, latitudinally instead of vertically, was counterproductive. Such a disposition meant that when he came to withdraw his own force, Bennett would be butting his way through Heath’s communications. 18 If Yamashita had planned the British Empire’s defence of Johore himself, he could not have acted more firmly in his own interests.

By now, it had become evident that the Japanese were speeding up their timetable of attack through their ability to turn the flanks of any linear defensive line across the narrow peninsula using amphibious hooks from the sea. In defensive terms, the Japanese approach meant that Bennett was confronted by Heath’s force positioned directly behind, instead of having an unimpeded run back along his own lines of communication with delaying positions in depth. Inevitably the two British forces would confound each other’s attempts to achieve a clean break before the advancing Japanese. To add to these problems, Bennett compounded matters by the manner in which he laid out the ‘Westforce’ defence.

For some time Thyer had been warning Bennett that the two main Japanese approaches—a down the main trunk road from Kuala Lumpur and from the coastal approach—deserved equal tactical consideration. It is clear from evidence that Bennett did not view the coastal approach with the gravity it deserved. In consequence, the general concentrated three of the four brigades of his command, ‘Westforce’, on the main trunk approach. Moreover, he deployed his weakest brigade, the 45th Indian, into 40 km of tangled, swampy river front, backed by only a single battery of Australian artillery.

These tactical dispositions meant that, from the outset, Bennett was committing himself to defeat in detail. He should have recognised that, if the Japanese broke through along the coast, his own flank would be turned. Bennett should also have appreciated that, even if he were not as severely threatened along the main trunk approach, he would have to conform to the withdrawal of the 45th Brigade or risk being cut off. Thyer was pressing him to give equal attention to the coastal approach by using two brigades there, and also two brigades in tandem along the main trunk approach. The general failed to heed the advice, and the outcome was exactly as Thyer had foreseen.

It should have been apparent to Percival and Bennett that it was operational speed or, in modern parlance, tempo that mattered to the Japanese. The Japanese forces lacked interest in using the jungle and were intent only on maintaining a high rate of speedy advance by moving down the main routes in Malaya with tanks, infantry and engineers. Their only use of the jungle was in order to cloak the movement of their two enveloping hooks. In short, Yamashita’s campaign was a Blitzkrieg rather than a jungle operation.

By refusing to believe that the coastal route was a main approach, Bennett neglected the defence of the area. His disposition of the 45th Indian Brigade at the Muar River gave the brigade no chance of countering a strong series of Japanese attacks by two regiments of a Japanese division. Battalions were split to create forward companies. The 7/6th Rajputana Rifles was responsible for 12 km of front in close country; the 4/9th Jats for the next 24 km inland; while the third battalion, the 5/18th Garhwal Rifles, was in reserve more than 16 km away at Bakri. These dispositions were not forced on Bennett. They were entirely his decision.

The three battalions of the 45th Indian infantry brigade on the left flank at Muar were inexperienced. Noting the infantry’s difficulty in having to defend simultaneously a river line, the brigade’s left flank and its rear against potential seaborne landings, Percival later wrote:

To make matters worse, the brigade commander had been told [by Bennett] to establish an outpost position across the river and two companies each of the [two] forward battalions were allotted to it. In my opinion this was a tactical error. The river obstacle should have been used as the basis of the defence and there should have been no more than a few patrols in front of it. I have the impression that Gordon Bennett’s attention was concentrated unduly on what he considered to be his main front and that he looked upon the Muar sector rather as a flank from which no real danger was likely to develop. 19

In addition, the 45th Brigade had originally been designated for desert service and many of its British company commanders were second lieutenants. Alan Warren gives a graphic account of soldiers of the 45th Brigade in action against the Japanese Imperial Guards:20

The Garhwali’s adjutant, Captain Rodgers, was now in command at Simpang Jeram, and he decided to form a close perimeter in a rubber estate. The estate was overlooked from higher ground but it was the best position available. The Japanese attacked the perimeter from the shelter of the village. The young riflemen were bewildered and they fired wildly. As the situation worsened Rodgers and Lieutenant Robson... each manned a bren gun at the forward corners of the perimeter, an indication of the low state of the sepoys’ training. Robson was shot in the chest crawling out to retrieve ammunition... Rodgers ordered a retreat shortly before he was killed. In the meantime a counter-attack towards Simpang Jeram by another Garhwali company had ground to a halt. By evening the battalion had been bundled back to Bakri. 21

In response to receiving a series of alarming reports from Brigadier H. C. Duncan, the 45th Brigade’s commander, Bennett belatedly sought to reinforce the brigade. He moved his divisional reserve, the 2/29th Battalion, into action, followed by the 2/19th Battalion from the 22nd Brigade on the East Coast.

Percival’s own mistakes then compounded Bennett’s errors. Despite the fact that the Japanese had already overcome the 45th Brigade’s defence, Percival decided on 17 January to make every effort to hold on to the Muar area. He sought to avoid a hurried withdrawal of the rest of ‘Westforce’ from the Gemas–Segamat positions to Yong Peng and Ayer-Hitam, where the main trunk road swung westward, making it dangerously within reach of a Japanese seaborne hook. Percival’s strategic thinking was dictated by a belief that the longer he could delay the Japanese, the greater his ability would be to mount a counteroffensive. Unfortunately, the problem Percival faced was that Japanese envelopment tactics meant that parts of his force were consistently being cut off and defeated in detail.

An example of Japanese tactics was the landing of a battalion from the sea at Batu Pahat. The actions of this battalion as a ‘cutoff force’, together with the speed of movement of the Imperial Guards, meant that Bennett’s entire left flank was compromised. Without the brilliant leadership of Lieutenant Colonel C. G. W. Anderson, who took command of the remnants of the 45th Brigade following Brigadier Duncan’s death in action, the entire force would have been cut to pieces by the Japanese.22 The brigade’s casualties were severe, and only a few soldiers eventually broke through the Japanese forces to reach their own lines at Yong Peng. Japanese troops bayoneted to death the wounded from Anderson’s group that had been left in and around a hut at Parit Sulong.

There were some outstanding tactical actions by Australian forces, including an excellent ambush by a company of the Australian 2/30th Battalion at the Gemencheh River near Gemas. The two-pounder guns of the Australian 2/4th Anti-Tank Regiment at Bakri also accounted for eight Japanese tanks. Yet what was needed was not isolated tactical victories but operational and strategic success.

Right from the beginning, Bennett’s thought processes tended to play into the hands of the Japanese. A close reading of Bennett’s diary, then of the Thyer papers in the Australian War Memorial, reveals a man deeply flawed by his egotism. For instance, worthwhile suggestions by his staff were usually treated as a form of treachery unless they accorded exactly with the commander’s own views. 23 Although Bennett had had a highly successful career as a front-line soldier in World War I, he had long since exceeded his military ceiling. The problem was that, while Bennett had continued to serve in the militia between the world wars, he had failed to keep abreast of new developments in warfare in any intellectual sense.

Percival's Command

General Yamashita’s explanation of the reasons for his own success in Malaya throw light on General Percival’s performance in Malaya in 1941–42. In a report written five months after the fall of Singapore, Yamashita was noticeably censorious of British command failure. The British commanders were, he wrote, ‘out-generalled, outwitted, and outfought’ by their Japanese counterparts. 24 Yamashita concluded, in particular, that Percival was personally responsible for a large share of the defeat. Percival, noted the Japanese commander, was a ‘nice good man’ who was neither a dynamic leader nor an inspiring general, and who ‘was good on paper but timid and hesitant in making command decisions’25

During the fighting on the mainland, and later on Singapore Island, Percival held innumerable conferences with his staff, seeking consensus, rather than giving clear, unambiguous orders. Woodburn Kirby described the scene:

At these conferences in the forward area, Percival arrived looking tired and worn and usually failed to take control. Bennett would then take the floor putting forward impracticable proposals until Heath would break in with a sensible suggestion based on sound military considerations, which Percival would accept and act upon. 26

At a press conference in Singapore not long before Percival’s force capitulated to the Japanese, Ian Morrison, the Australian correspondent of The Times newspaper, noted of Percival that ‘much of what the general said was sensible. But never have I heard a message put across with less conviction, with less force... It was embarrassing as well as uninspiring’.27

General Bennett's Mistakes

It is clear that Bennett made three major errors in his defence of northern Johore. First, his design for battle was limited, as seen in his belief that relatively small local actions such as the Gemas ambush and aggressive patrols might succeed in halting the Japanese and cause them to rethink their planning. Second, by failing to hold the Muar River in greater strength, Bennett opened his own ‘back door’ in a manner that the Japanese were bound to exploit—even though they also planned to use the main trunk route as an equally important thrust line. 28 Third, and probably most serious of all, Bennett told his ‘Westforce’ orders group on 10 January 1942 that there would be no further withdrawal from the forward positions assigned to them. As a commander, and given shortages of equipment, he should have known that his officers were incapable of carrying out such an order.

It is useful to contrast Percival’s defences in Malaya in 1942 with those of General William Slim in Burma at Imphal and Kohima in 1944. Slim turned his positions into self-sufficient and pre-stocked ‘strong points’ that were resupplied by air. Casualties were also either evacuated by air, or medical resources were bolstered in order that those who were badly wounded could remain in place for extended periods of time. As a result, Slim’s troops outlasted the pressure of Japanese attack. However, in Malaya neither Percival nor Bennett had prepared such a detailed plan. Moreover, they lacked both the air assets to perform essential logistic tasks and the equipment to stop the Japanese, who were replenished from the sea and were thus capable of outflanking British defences. Thus, despite having told his commanders that there would be no withdrawals, Bennett was incapable of carrying out his own strategy. In consequence, when the Imperial Guards broke through at Muar, his main force was compelled to withdraw or risk being cut off.

Conclusion

Both Percival and Bennett presided over a military disaster. Percival demonstrated an inability to ‘grip’ his command, or to inspire it to greater effort. Never once, in the fighting from the Thai border to Johore, did he ever look like wresting the initiative from the Japanese. In Johore, he attempted to hold the Muar position for far too long, thus allowing the Japanese to trap many forward British and Commonwealth troops who then had to fight their way out, taking many casualties and almost all their equipment in the process. For all his haughty declarations that he would stop the Japanese, Bennett made decisions that ensured his becoming, in Lodge’s words, ‘but one of a team of defeated generals’. 29 At the Johore Straits, Bennett could only ruefully survey his own defeat. ‘This retreat,’ he remarked, ‘seems fantastic. Fancy 550 miles in 55 days—chased by a Jap [ sic ] army on stolen bikes without artillery’. 30 Worse was to follow, and Bennett’s subsequent defeat on Singapore Island was to complete the collapse of Malaya.

Endnotes

1 On Percival’s command in Malaya see Clifford Kinvig, Scapegoat: General Percival of Singapore, Brassey’s, London, 1996; and ‘General Percival and the Fall of Singapore’, in Brian Farrell and Sandy Hunter (eds), Sixty Years On: The Fall of Singapore Revisited, Eastern Universities Press, Singapore, 2002, pp. 240–70.

2 On Bennett see A. B. Lodge, The Fall of General Gordon Bennett, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1986.

3 Major General S. Woodburn Kirby, Singapore: The Chain of Disaster, Cassell, London, 1971.

4 Quoted in John Ramsden, Man of the Century: Winston Churchill and His Legend since 1945, Harper Collins, London, 2002, p. 206.

5 Kinvig, ‘General Percival and the Fall of Singapore’, p. 246.

6 Alex Danchev and Daniel Todman (eds), Field Marshal Lord Alanbrooke, War Diaries 1939–1945, University of California Press, Berkeley, CA, 2001, pp. 206–7.

7 John Ferris, ‘ “Worthy of Some Better Enemy?”: The British Estimate of the Imperial Japanese Army 1919–41, and the Fall of Singapore’, Canadian Journal of History, August 1993, vol. XXVIII, p. 249; and ‘Student and Master: The United Kingdom, Japan, Airpower, and the Fall of Singapore 1920–1941’, in Brian Farrell and Sandy Hunter, Sixty Years On: The Fall of Singapore Revisited, pp. 94–122.

8 Woodburn Kirby, Singapore: The Chain of Disaster, pp. 74–5.

9 ‘Tactical Notes for Malaya’, quoted in Lionel Wigmore, The Japanese Thrust, Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1957, p. 67; and Australian War Memorial, Japanese Army: Notes on Characteristics, Organisation, Training etc., 940 540952 J469, issued by the General Staff, Army HQ, Melbourne, September 1940.

10 John Coates, Bravery Above Blunder: The 9th Australian Division at Finschhafen, Sattelberg and Sio, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1999, pp. 246–7. There is evidence that the Far East Combined Bureau (FECB) and the Joint Intelligence Committee in London were, by early 1941, making reasonably accurate estimates of what the Japanese might do. However, their effectiveness was nullified because Brooke-Popham, the Commander-in-Chief, was ‘temperamentally disposed to believe that the Japanese simply would not dare attack Malaya’. See Richard J. Aldrich, Intelligence and the War against Japan, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2000, p. 51.

11 Wigmore, The Japanese Thrust, p. 67.

12 Ibid.

13 E. G. Keogh, Malaya 1941–42, Directorate of Military Training, Melbourne, 1962, p. 179.

14 See Alan Warren, Singapore: Britain’s Greatest Defeat, Talisman, Singapore, 2002, p. 37. Brigadier D. S. Maxwell, the commander 27th Brigade, and a friend of Bennett, later told Gavin Long that ‘what I was to emphasise is: the training of infantry in Malaya was due to [Brigadier] Taylor. I only carried on his methods’, AWM 67, Item Notebook 2/109, Interview with Brigadier D. S. Maxwell.

15 Quoted in Lodge, The Fall of General Gordon Bennett, p. 119.

16 Wigmore, The Japanese Thrust, p. 82.

17 Bennett Diary, 2 January 1942.

18 The revised plan also proposed to concede the Tampin Gap without a fight. Here, the trunk road, railway and coastal route come much closer together than further south and the gap could have been held more economically. It is a criticism made by Woodburn Kirby, Singapore: Chain of Disaster, p. 186.

19 Lieutenant General A. E. Percival, The War in Malaya, Eyre & Spottiswoode, London, 1949, p. 222.

20 Warren, Singapore 1942: Britain’s Greatest Defeat, esp. pp. 160–70.

21 Ibid., p. 161.

22 Anderson, normally the Commanding Officer of the 2/19th Battalion, was later awarded the Victoria Cross for his outstanding leadership.

23 For instance, when the idea of the Gemas ambush was first raised, Bennett intended that it should aim to destroy a Japanese brigade-sized force. Thyer and Maxwell were able to head him off by experimenting with the concept at Jemaluang on the east coast [later the scene of a successful ambush by Taylor’s 22nd Brigade]. The experiment demonstrated that attempting to ambush an entire brigade far exceeded the capacity of Australian communications to control such a large killing area. Bennett then dropped the idea. AWM93 Records of the War of 1939–45: Colonel J. H. Thyer.

24 Akashi Yoji, ‘General Yamashita Tomoyuki: Commander of the Twenty-Fifth Army’, in Farrell and Hunter, Sixty Years On: The Fall of Singapore Revisited, p. 197.

25 Ibid.

26 Woodburn Kirby, Singapore: The Chain of Disaster, p. 205.

27 Ian Morrison, Malayan Postscript, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1943, pp. 156–7.

28 Lodge, The Fall of General Gordon Bennett, ch. 5.

29 Ibid., p. 114.

30 Bennett Diary, 31 January 1942.