Abstract

Australia is a middle power that must find ways to ‘deter without escalation’; however, we are not yet able to offer military options in pursuit of this objective. How does Army tie into the joint force and our regional geography, remaining grounded in formation tactics while becoming an integral part of a ‘joint federated targeting system’? More simply: how can we become as dangerous and survivable as possible? This article suggests a force design that offers a radically different set of relationships among and between current force elements and prospective strike capabilities. This proposal is a highly dispersed and dramatically flattened network of nodes, aggressively interwoven with deception measures and capable of unconventional sustainment. It is envisioned as scalable and, arguably, offers advantages as a way of employing strike capabilities nested alongside more familiar tasks. A dual capacity for both close combat and strike needs to reside within the same task groupings; close combat enables strike options and strike enables close combat at different points in space and time.

Introduction

Radically different force designs and employment concepts are required to underpin the success of joint and whole-of-government efforts to shape and deter1 in our region. It is unclear what the relationship between strike assets, like prospective land-based maritime strike missiles, and the joint forces conducting a broad range of potentially concurrent operations should be.

The 2020 Defence Strategic Update2 has been rightly read by commentators as a ‘sombre’ document.3 Graeme Dobell has summarised it thus: ‘Order suffers. Coercion rises. Geography is back’. War in the Indo-Pacific, ‘while still unlikely, is less remote than in the past’.4 Importantly for what war might look like, there is an emerging consensus that defensive fires are ascendant or even dominant once again, particularly in the maritime.5

While much has been read into the changes present in the Strategic Update, as Rory Medcalf has observed:

… we should be under no illusions that this is a fully independent Australian defence strategy, there is still also that continued great reliance on the US and a whole range of partners in the region’.6

Moreover, in Brendan Sargeant’s summary, we are still ‘banking a lot on technology and we’re banking a lot on the ability to create big effects with a relatively small, high-tech force’.7

In the last issue of this publication, Lieutenant Colonel Nick Brown highlighted the need for prospective long-range rocket artillery systems to be ‘“tied in” with other defence capabilities and to their geography’, with a particular emphasis on embedding such capabilities within our range of regional relationships and how deterrence effects need to be articulated accordingly.8 He also noted the need to manage the dilemmas of our technical relationship with the US.9

This article asks related questions: how does Army make itself nastiest and most survivable in our region? How do we hurt our adversaries at reach and then live to fight another day?10 What options do we offer with the rest of the joint force to ‘hold potential adversaries’ forces and infrastructure at risk from a greater distance, and therefore influence their calculus of costs involved in threatening Australian interests’?11 How do we remain grounded in formation tactics while expanding the tactical bubble from 30 kilometres to 1,000 kilometres and integrating into what has been termed a ‘joint federated targeting system’,12 inclusive of new missile systems?13 Moreover, we are a middle power that must off-ramp regional conflict and find ways to ‘deter without escalation’:14 we are not yet able to offer military options in pursuit of this objective.

In what follows I briefly sketch a design that proposes a radically different set of relationships among and between our extant force and prospective strike capabilities. This proposal is a highly dispersed and dramatically flattened network of nodes, aggressively interwoven with deception measures and capable of unconventional sustainment. It is envisioned as scalable and, arguably, offers advantages as a way of employing strike capabilities nested alongside more familiar tasks. My focus is on the parts of joint capability ‘owned’ by Army; however, there is clearly only a joint fight.

It bears noting that my initial draft of this paper was developed without reference to either internal Australian Army staff work on the future force, or the new US Marine Corps concept ‘Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations’ (EABO).15 That it bears similarities to the latter reflects the like adaption pressures facing other militaries, too. After revisions to this paper, EABO is now rightfully present in the discussion that follows.

One issue re-emerges very clearly in this paper on multiple occasions, and I return to it in the conclusion: any vision of operating strike capabilities north of the Australian continent faces huge political challenges vis-à-vis our neighbours and partners. Relatedly, capabilities aimed at deterrence play a role in prospective regional crisis dynamics. Unless government adopts a strategic posture in which land-based missiles are deliberately tethered to a continental, ‘Fortress Australia’ approach, then these challenges are clearly implied in the acquisition of missile systems.

This paper has two sections. In the first, I outline a proposal for a highly dispersed task group which integrates latent strike capabilities. In the second, I discuss some potential advantages of this proposal as well as some of the clear challenges it would face.

Highly Dispersed Task Groups and Latent Strike

Analysts have frequently called for the Australian Army to become ‘more of a Marine Corps’ in response to contemporary challenges.16 Such a change is not good enough, though we should pay heed to some of the dramatic changes allies and adversaries are making. It should raise alarm bells for Army as an organisation that key peer organisations are, for instance, doing away with heavy armour while we are reinvesting therein.17 The US Marine Corps is doing so as part of a serious shift towards contributions to joint sea denial as the principal task at hand.18 We should take heed of this shift but merely aping it will not do. In this section, I present a highly schematic and partial concept of operations for the archipelagic setting.

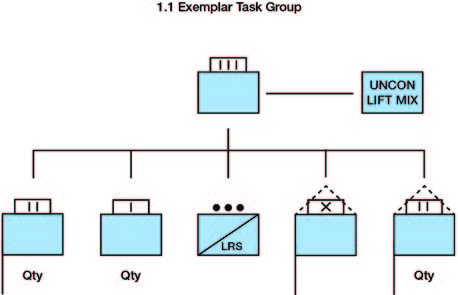

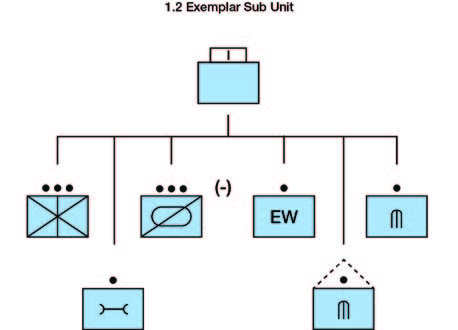

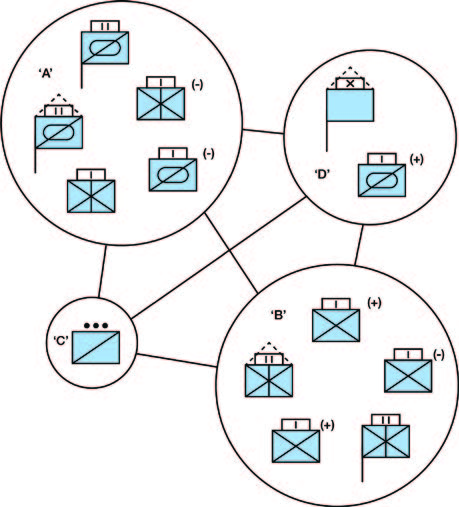

Figures 1 and 2, along with Table 1, summarise a force design which might underwrite the concept of operations, which follows in Figure 3. Readers should first familiarise themselves with these graphical summaries before reading on.

The concept might be summarised as follows. Robust but small combat team-approximate elements or nodes are dispersed in a maritime setting, paired with a mix of strike assets and deeply interwoven with decoy measures. To reiterate: I am not suggesting that within such constructs, long-range strike capabilities and infantry platoons will be working to the same immediate ends in the sense of traditional ‘teaming’. I am articulating a possible way in which strike assets might be placed on the ground amongst other forces and other missions in a particular geography.

Perhaps initial deployment has occurred in the form of a disaster relief operation, and a small footprint of Australian forces have been left in situ after that initial activity because of concerns about the intentions of a competitor. Perhaps part of this task grouping has been deployed as part of a regular training rotation with a regional partner nation, or perhaps a regional confrontation or crisis is already rapidly developing, and a task group is deployed in direct response to that deterioration.

This dispersed posture offers options for concealing layered strike capabilities—in terms of both land-based missile systems and integration with other joint fires—within a joint grouping that may well be conducting a range of other taskings. Those strike capabilities might be openly demonstrated or remain veiled until being deliberately cued or triggered. The posture on the ground includes the organic use of long-range reconnaissance elements as part of a sensor mix, though they are deliberately not depicted as Special Operations capabilities. Their pedigree is not important, and appropriately equipped reconnaissance elements organic to combat brigades could accomplish some such taskings.

Likely adversary responses might be gamed and manipulated, for instance, in the deliberate unveiling of certain friendly strike assets to enable counter-counter-strike. A simple example of this might be the purposeful exposure of a targeting radar or dummy headquarters to attract an adversary strike, in order to allow us to jointly target the scarce adversary asset that carries out that strike.

In these groupings, the close combat and strike capabilities can be seen as a pair with shifting responsibility for a ‘protect’ function or ‘guard’ task. The close combat force provides intimate protection for missile systems, opens options for deception, and allows the grouping as a whole to fight for position so strike assets can ‘take the shot’ if needed. (The capability ‘taking the shot’ might be an integrated land-based missile, but it might also be an F-35 or a naval platform). Under other conditions, strike capabilities protect the grouping from adversary strike capabilities and—necessarily tied in with other joint platforms and sensors—mitigate the risk of isolation in the maritime.

Critical nodes in both command and force terms are minimised. I propose that a number of equivalent command nodes should co-exist, operating either cooperatively within an established operational design or rotating supremacy as ‘first among peer’ headquarters. This is proposed both to provide a level of redundancy to adversary strike functions which will presumably target such nodes, and to reinforce the deception effect intended to be pervasive through this concept. This will be regarded by some as a ‘magical’ black box of a proposal and clearly needs development and experimentation. Nonetheless, we need to do something about the risk of isolation and destruction of any grouping in the maritime that relies on tenuous command links to a higher headquarters that solely retains key authorities.

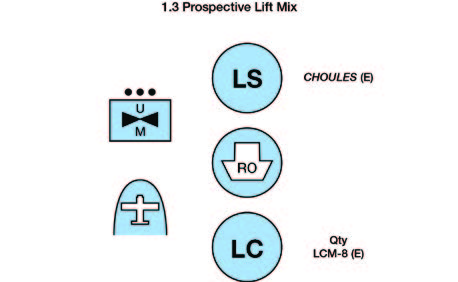

Inherent in this concept is a variable level of reliance on a civilian and military logistics mix, at least in terms of the large platforms used within the logistics architecture. What might the ‘prospective lift mix’ solution in this kind of concept actually look like? On the one hand, it may well look like the dedicated use of military and naval assets. If this kind of posture were a national main effort, it is not hard to envisage how it might be emplaced and sustained using landing helicopter docks (LHDs), landing craft, C-17s and C-130s. Table 1 gives some idea based on very rough rules of thumb of how it might be achieved in circumstances where this kind of operation is a supporting rather than a main effort, or where scarce military assets are being husbanded, or where unconventional sustainment options might offer a means of deceiving or dislocating an adversary.

Unmanned platforms are not depicted in the organisational diagrams as it is taken as an assumption that such systems will be integrated within teams at all levels. There is opportunity here to team cheap and autonomous logistics platforms, for instance, as a way to sustain dispersed elements in the maritime. I have also not depicted the organisational integration of regional partner forces, which to varying extents will surely be a feature of our operations.

Uniformed readers will no doubt immediately note the use of the ‘regimental’ designator for this grouping, as well as the replication of the organisation in conventional ‘tree’ form alongside a non-hierarchical depiction. The former is an acknowledgement that, at least in an administrative capacity or in the force generation setting, some coordinating function is required. I mean little by it other than it probably should not look like a familiar formation headquarters. The latter is simply intended to mirror the above proposal for flat, co-existing command nodes.

Figure 1. Exemplar task organisation

Missile systems integrated into low-level groupings though not tasked with the same immediate tactical ends

Figure 2. A representative ‘flat’ task grouping that lacks conventional command hierarchy

Figure 319. Schematic concept of operations: dispersed, latent strike

Table 1. Generating a representative ~1000 pax lift with significant cargo capacity

| Lift asset | Indicative capacity |

| Choules (E) | ~350 troops or ~30 heavy A vehicles or ~150 light vehicles |

| Large commercial Roll-on/Roll-off vessel, e.g. Tasmanian Achiever II20 | 700 x 20-ft container equivalents, 70 civilian car equivalents and 70 civilian trailer equivalents |

| Medium-size commercial RO/RO vessel, e.g. MV Minjerribah | ~400 passengers and ~50 civilian car equivalents |

| 2 x 737-800 or equivalent | ~170 passengers each for ~340 pax |

| Single 737-300 freighter | Maximum of 17 340 kg of cargo |

Discussion

Clearly there are potential advantages and apparent challenges with this proposal. At least at this most abstract level, this concept attempts to offer a way of using forces that is relevant to the shaping and deterrence of potential regional adversaries. Further, a willingness to consider the use of unconventional logistics options offers opportunities to overcome a major constraint facing the joint force—our extremely constrained lift capacity across all the services—and the resulting limit on the options available to government.

Perhaps most importantly, this kind of concept arguably increases the strategic utility of many existing assets. This concept articulates how we might deliberately design and posture a force to achieve certain ‘shape’ and ‘deter’ effects, rather than simply uplifting conventionally generated minor joint task force and combat brigade-like formations and tasking them to do so. It is worth making clear here that I have an appreciation that both ‘shape’ and ‘deter’ are functions broader and more expansive than anything this concept can achieve; I am discussing a piece of the puzzle.

That aside, I tender that this proposal offers some degree of scalability and simultaneity in a campaign, and perhaps even the possibility of manipulating ‘liminal’ zones, to borrow David Kilcullen’s language.21

What does this mean? First, it relates to scalability and simultaneity. The variable size and composition of each dispersed force element means that these elements could conceivably be established and maintained through non-specialist logistics platforms, including platforms the size of ships and airframes in the Australian commercial fleets. This offers the potential to establish this part of an integrated campaign without investing it with assets like LHDs.22 This might offer a degree of sustainability for those key assets over a drawn-out period. It might also mean that those assets could be allocated to an expeditionary effort elsewhere, for instance, or (particularly with regard to Air Lift Group) could remain allocated to the support of intensive air operations.

Some further brief notes are needed about the ‘lift mix’ canvassed above. To be clear: I am not suggesting that 737s or civilian vessels should be envisioned as continually flying in and out of contested operating areas. I am suggesting that in certain scenarios it is possible to deploy and sustain armoured vehicles, HIMARS-type23 fires assets and personnel using a careful blend of dedicated lift platforms and non-specialist logistics capabilities. The 1999 Timor experience of sustainment using the catamaran Jervis Bay24 is a good indication of what sustainment might look like for a posture potentially commencing as the dispersed conduct of stabilisation or training activities, but we could go much further than this example. We might also give serious consideration to what we envision withdrawing in extremis. For example, PMV and Hawkei type vehicles can probably be deliberately abandoned if necessary. I also do not wish to downplay the significant complexities involved with, for instance, freight handling and port facilities for commercial Roll-on/Roll-off vessels or freight aircraft. It would be madness, however, not to consider how we might stretch the commercial capacities we do have on hand if we were required to do so.

The potential for ‘liminal’ manipulation is linked to these considerations but quite different still. The establishment of a posture like this, somewhere in the region, need not begin as the establishment of a layered net of striking nodes. Rather, forces could (with or without deceptive intent) be emplaced in a given setting conducting tasks elsewhere on the spectrum of operations. Combat teams might be conducting training or stabilisation activities, for instance, in a deteriorated geopolitical context. Given a certain baseline of command-and-control systems it might be feasible to escalate this posture very rapidly from a relatively benign inception.

If national decision-makers did seek to more explicitly manipulate ‘liminal’ zones, this might be possible, too. The capability settings of a certain node might be deliberately ratcheted above the needs of a stated task, while the possession of high-end capabilities by others within a (latent) network might remain masked. Our adversaries have different political decision-making considerations, so this would not simply be a replication of what Kilcullen has suggested adversary approaches are doing to ‘the West’ and the vulnerabilities of our own political systems.25 Nonetheless, this approach is a specific way of ‘shaping’ a threat, and would be aimed at creating uncertainty about the threat and risk level of prospective adversary courses of action, in the minds of both military commanders and political decision-makers. We need to offer a credible vision of how we could employ joint forces to shape a threat in a maritime setting, rather than merely targeting them after they have acted first.26

This concept also, of course, presents a number of clear and marked disadvantages and challenges. First and foremost, the adversary gets a vote and their own influence. This is perhaps the most pressing concern raised by Ben Wan Beng Ho in his criticism of the US Marine Corps’ EABO.27 In short, EABO seeks to:

… further distribute lethality by providing land-based options for increasing the number of sensors and shooters [available] … They may also control, or at least outpost, key maritime terrain to improve the security of sea lines of communications … and chokepoints or deny their use to the enemy, and exploit and enhance the natural barriers formed by island chains.28

A passive view of regional partners and their willingness to allow the basing of strike assets on their soil, implicit in EABO, is problematic,29 and is also a real concern in relation to what I have sketched here. Two responses to this concern are apparent. First, this risk returns us to what Lieutenant Colonel Brown describes as the regional ‘tie in’.30 The thoroughgoing effort required to achieve and maintain potential host nation consent for an assertive Australian posture is clearly inescapable.

Second, there must be an emphasis on how strike capabilities are integrated within the full range of missions we might be conducting in the region. Part of the solution here might lie in the ability, latent or realised, overt or discrete, to nest strike within the range of other tasks we are likely to undertake in the region. That is precisely why we need some conceptual grounding (like that proposed here) for how strike capabilities are deployed which is not divorced from the functions traditionally provided by the land force.

The ‘operational concerns’ identified by Ben Wan Beng Ho regarding EABO are also live concerns in relation to what I have sketched here: this is ‘the conundrum of balancing lethality and signature management’.31 For example, ‘the 110-plus-mile striking reach of the [Naval Strike Missile] will be for naught if the weapon system can receive data only from a ground-based radar with coverage of 18–25 miles’, and any movement of missile platforms or additional connectivity with joint sensors rapidly increases their likelihood of detection.32

Again there seems to be a twofold response to this concern. First, part of the challenge may be technically soluble, with the development of more discrete and secure communications links, for example, along with practised procedures which allow platforms to remain ‘off’ for as long as possible until their exposure if necessary. Second, we must double down on the unconventional aspects of the concept I have sketched. We can better eschew the blatant signatures of logistics platforms, for example, if we have a wider range of much more numerous, non-military sustainment options.

Perhaps the most significant challenge is the real vulnerability of individual nodes. We have our own ample historic experience of the isolation and loss of forces in the near region: the disasters of ‘Sparrow Force’ in Timor33 and ‘Lark Force’ at Rabaul34 in 1942 are sobering examples of the real risk of isolation and destruction facing disaggregated elements in the archipelago. There can be no disputing that fundamentally the constituent elements, and the aggregated land combat weight of the groupings, are weak. While in certain circumstances—for example, where we might choose to disperse multiple nodes on a single island— we might envision some useful concentration of forces physically for the purposes of land combat in the traditional sense. Even in this limited circumstance, however, the weight of a force-concentrated element is unlikely to muster more than a reinforced battlegroup. In this light, clear preconditions need to be established for the deployment of vulnerable forces. For instance, in facing an adversary with significant marine and airborne capabilities, perhaps persistent monitoring of known adversary high-mobility formations is required.

This challenge also reflects a dilemma that arguably makes force design even harder for Army than for its counterpart services: the tension between capabilities with the ability to have long-range strike and other ‘strategic’ impacts directly, and those that are likely to survive and win in a close fight. Brigadier Ian Langford’s recent framing of the problem in terms of the need to reconcile ‘close combat’ and ‘formation tactics’ with the acquisition of serious strike capability is another way of saying this. This problem fundamentally influences professional debates about force design in often unspoken ways. It still remains the case, to once again borrow Brigadier Langford’s words, that in many circumstances the ‘entry price is a metre of steel’.35

A dual capacity for both close combat and strike needs to reside within the same task groupings; close combat enables strike options and strike enables close combat forces at different points in space and time. The size of each element and the density of a posture like this would need serious adjustment depending on threat and geography, but it may well not be possible to calibrate acceptably at all.

The command-and-control innovations proposed to make this network posture more robust can also be seen to represent a significant risk. Hierarchical command-and-control arrangements exist for a reason and, when balanced, underwrite unity of effort and other consensus principles of military operations. Given that the object of this concept is not principally close combat, it does not seem completely outrageous to suggest that the ‘Rule of Threes’ and concerns about span of command are perhaps less pressing here than is conventionally the case.36 Nonetheless the suggestion that unified action could be credibly threatened by a force lacking a single, clear commanding element is open to challenge.

My final and bleakest observation is that this may simply be a tactical response to a problem that is strategic in the highest sense. Our marginal benefit or comparative advantage in a regional setting (as White rightly points out, too37) is never going to be a numerically heavy deployment of close combat forces alongside large Asian partners or against large Asian adversaries. This will always be the dilemma of ‘walking amongst the giants’, to use Ross Babbage’s language.38 But in a context in which prominent American analysts are concerned about their own ability to generate sufficient strike capabilities,39 it bears noting that we may simply not be capable of credibly holding adversaries at sufficient risk.40

Conclusion

We can provide utility to government by offering force options that hedge the risks inherent in our choice to invest in scarce, high-end capabilities, and by finding credible ways of operating in the maritime with prospective strike capabilities. In a markedly deteriorated near-future regional setting, such options probably look much different from our reflexive use of special operations and our nominal joint task groups and their combined arms formations.

This paper is intended as provocative and partial. If nothing else, it should draw attention to the political and systems costs that must be paid if we are to actually ‘get after’ long-range strike. The challenges present in what I propose here have broader implications that relate to missiles and our ambitions to shape and deter in the region generally. The challenge first and foremost is, rightly, one of regional sovereignty. Under what conditions are regional partners likely to allow us to deploy such potentially provocative capabilities on their soil? This draws us back to Lieutenant Colonel Brown’s recent contribution in the first instance. Further, the way we envision employing capabilities is critical to evaluating our possible contribution to security dilemmas and our potential alliance commitments. For instance, are we willing to contribute to potentially disastrous crisis instability in the region through the deployment of such capabilities, which are (of course) not innately defensive?41 Even if we are, can we generate enough risk to an adversary that this is even worth doing? If we do not have good answers to these questions then it is not clear we have our ends, ways and means coherently aligned.

Regarding the details of this concept on its own terms, serious thinking would be required on, among other things, the limits of strike range bands and robust communications systems on dispersion; the linking of very low-level force elements and headquarters nodes with potentially sensitive, or at least scarce and protected, joint sensors; how that same integration can and cannot occur with regional partners who lack a requisite level of capability and security; how and where we might exercise these kinds of operations; and whether our force generation structure would be capable of underpinning such a concept of operations.

About the Author

Captain Will Leben is an Australian Army officer and General Sir John Monash Foundation Scholar currently at Oxford.

Endnotes

1 As of the 2020 Defence Strategic Update, ‘shape’ is now a central word in the articulation of Australian defence policy. I mirror that here and use it (imprecisely) to refer to the use of various levers of power to influence the strategic environment, short of the actual use of force. See Department of Defence, 2020, 2020 Defence Strategic Update (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia).

2 Ibid.

3 Graeme Dobell, ‘Australia’s strategic update by the numbers’, The Strategist, 13 July 2020, at: https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/australias-strategic-update-by-the-nu…

4 Ibid.

5 Jonathan D Caverley and Peter Dombrowski, 2020, ‘Cruising for a Bruising: Maritime Competition in an Anti-Access Age’, Security Studies 29, no. 4: 671–700. See also Albert Palazzo ‘Deterrence and Firepower: Land 8113 and the Australian Army’s Future (Part 1, Strategic Effect)’, Land Power Forum, 16 July 2020, at: https://researchcentre. army.gov.au/library/land-power-forum/deterrence-and-firepower-land-8113-and-australian-armys-future-part-1-strategic-effect

6 Rory Medcalf, ‘Australia’s Defence Strategy Update’, National Security Podcast, 8 July 2020, at: https://nsc.crawford.anu.edu.au/news-events/news/17089/podcast-australi…

7 Brendan Sargeant in ibid.

8 Nick Brown, 2020, ‘Riding Shotgun: Army’s Move to the Strategic Front Seat’, Australian Army Journal XVI, no. 2: 5–24.

9 Ibid., 19.

10 My thanks again to one of my reviewers for allowing me to borrow these phrases.

11 Defence Strategic Update, 27.

12 Both of these questions are posed in Ian Langford, 2020, ‘Army Force Structure Implementation Plan’ (seminar recording), 6 August 2020, at: https://researchcentre. army.gov.au/library/seminar-series/army-force-structure-implementation-plan

13 Acquisition announcements continue apace on this front. In addition to Army’s prospective missile acquisitions, see further strike acquisitions for Navy: Department of Defence, ‘Morrison Government Boosts Maritime Security’ (press release), 25 January 2021, at: https://www.minister.defence.gov.au/minister/lreynolds/media-releases/ morrison-government-boosts-maritime-security

14 Langford, 2020.

15 US Marine Corps, ‘EABO’, at: https://www.candp.marines.mil/Concepts/Subordinate- Operating-Concepts/Expeditionary-Advanced-Base-Operations/ *Source is located on a restricted network and can only be accessed by individuals with access to the network.

16 Graham does so but instead with a welcoming view of the significant changes occurring in the USMC. See Euan Graham, 2019, ‘Lessons for Australia in US Marines’ New Guidance’, The Strategist, 12 August 2019, at: https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/ lessons-for-australia-in-us-marines-new-guidance/

17 Shawn Snow, 2020, ‘The Corps is Axing All of Its Tank Battalions and Cutting Grunt Units’, Marine Corps Times, 23 March 2020, at: https://www.marinecorpstimes.com/ news/your-marine-corps/2020/03/23/the-corps-is-axing-all-of-its-tank-battalions-and-cutting-grunt-units/. British plans are less clear at this stage but see also Jonathan Beale, 2020, ‘British Army Could Axe Ageing Tanks as Part of Modernisation Plans’, BBC News (online), 25 August 2020, at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-53909087

18 USMC, 2020, ‘Littoral Operations in a Contested Environment’, at: https://www.candp. marines.mil/Concepts/Subordinate-Operating-Concepts/Littoral-Operations-in-a- Contested-Environment/ *Source is located on a restricted network and can only be accessed by individuals with access to the network.

19 Geographically minded readers will recognise the terrain used here as the Aegean Sea. This was chosen as a politically neutral maritime setting, at least for an Australian author.

20 The Australian-flagged shipping fleet can be explored by downloading the Australian Maritime Safety Authority Register and filtering for vessel types and sizes. See ‘List of Registered Ships’, accessed 24 September 2020, at: https://www.amsa.gov.au/ vessels-operators/ship-registration/list-registered-ships Discussions have occurred on Australia’s (lack of) commercial capacity—see Sam Bateman, 2019, ‘Does Australia Need a Merchant Shipping Fleet?’, The Strategist, 4 March 2019, at: https://www. aspistrategist.org.au/does-australia-need-a-merchant-shipping-fleet/. The Australian commercial aviation fleet can also be explored relatively easily by searching the Civil Aviation Safety Authority Register for relevant operators and types. See ‘Aircraft Register Search’, accessed 24 September 2020, at: https://www.casa.gov.au/aircraft-register?f%5B0%5D=field_ar_reg_op_name…

21 David Kilcullen, 2020, The Dragons and the Snakes: How the Rest learned to Fight the West, (London: Hurst and Company).

22 The Force Structure Plan does envision investment in our lift capabilities—the replacement of Choules with two vessels, new watercraft and new landing craft. We still face huge limitations, with a doctrinal ‘Amphibious Ready Group’ still representing a ‘single shot’ of our major lift capabilities, for instance. The return of capabilities that allow Army to independently project ‘up the Sepik’ is nonetheless noteworthy, as noted in Langford, 2020. For new capabilities see Department of Defence, 2020, 2020 Force Structure Plan (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia), 41, 45.

23 I am not concerned in this article with the exact missile systems Army is likely to acquire. I take HIMARS as representative enough for my purposes, though also note that some analysts have expressed concern about the details of a HIMARS mounted ASuW missiles. For example see ‘US Marines Select an Anti-Ship Missile’, The Diplomat (online), 9 May 2019, at: https://thediplomat.com/2019/05/us-marines-select-an-anti-ship-missile/. See also Beng Ho, cited below.

24 Royal Australian Navy, 2020, ‘HMAS Jervis Bay (II)’, at: https://www.navy.gov.au/hmas-jervis-bay-ii

25 Kilcullen, 2020.

26 While tangential to this paper, this is the biggest shortcoming of Hugh White’s prominent attack on Australia’s defence posture. While White offers a compelling analysis of region and our place within it, it is unclear what a campaign in the region looks like for White beyond the purchase of submarines and jets and their employment in an elegant targeting process from the Australian continent. See Hugh White, 2019, How to Defend Australia, (Carlton: La Trobe University Press).

27 Ben Wan Beng Ho, 2020, ‘Shortfalls in the Marine Corps’ EABO Concept’, Proceedings 146, no. 7, at: https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2020/july/ shortfalls-marine-corps-eabo-concept

28 USMC, ‘EABO’.

29 Beng Ho, 2020.

30 Brown, 2020.

31 Beng Ho, ‘Shortfalls’.

32. Ibid.

33 Daniel Minchin, 2017, ‘Dutch Timor and Sparrow Force—1942’, Virtual War Memorial Australia, at: https://vwma.org.au/research/home-page-archives/dutch-timor-and-sparrow…

34 Hank Nelson, 1992, ‘The Troops, the Town and the Battle: Rabaul 1942’, Journal of Pacific History 27, no. 2: 198–216. Of course, thankfully the Japanese in turn had their own experience of bypass and isolation. See also Jim Lacey, ‘The “Dumbest Concept Ever” Just Might Win Wars’, War on the Rocks, 29 July 2019, at: https:// warontherocks.com/2019/07/the-dumbest-concept-ever-just-might-win-wars/

35 Langford, 2020.

36 See ‘Chapter 6: Tactics and Organisations’ in Jim Storr, 2009, The Human Face of War (London: Continuum).

37 White, 2019, 196–197.

38 Ross Babbage, 2008, ‘Learning to Walk Amongst Giants: The New Defence White Paper’, Security Challenges 4, no. 1: 13–20.

39 TX Hammes, 2021, ‘The Navy needs More Firepower’, Proceedings 147, no. 1, at: https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2021/january/navy-needs-more…

40 Al Palazzo is among those who have commented on the required size of missile capabilities ‘if regional powers are to take the capability seriously’—see Albert Palazzo, 2020, ‘Deterrence and Firepower: Land 8113 and the Australian Army’s Future (Part 2, Cultural Effect)’, Land Power Forum, 21 August 2020, at: https://researchcentre.army. gov.au/library/land-power-forum/deterrence-and-firepower-land-8113-and-australian-armys-future-part-2-cultural-effect

41 For a worrying analysis of what we might be contributing to, see Caverley and Dombrowski, 2020.