Abstract

Accelerated Warfare1 describes how Australia’s region is increasingly defined by a changing geopolitical order and operating spectrum of cooperation, competition and conflict. While Accelerated Warfare is the title of Army’s futures statement, that operating spectrum nonetheless reflects Army’s first 40 years. This paper examines how Army confronted those challenges as Australia’s relationship with Imperial Japan transitioned from one of security cooperation, through competition and confrontation to conflict.

Cooperation

On 30 January 1902, the British and Japanese government representatives signed the Anglo-Japanese Alliance, ending Great Britain’s era of ‘splendid isolation’. Coming just over a year after Australian Federation, the alliance:

was, on the whole, received in Australian political and commercial circles ‘with marked expressions of approval.’ The Alliance was seen as a check against a Russian fleet from Vladivostok or a German fleet from the Chinese Sea, and as a guarantee to the trading interests of Australia in the Far East.2

The fledgling Australian Government’s relief proved short-lived. The 1904–05 Russo-Japanese War coincided with the withdrawal of Britain’s five China Station battleships to the North Sea to redress the balance against Germany, presenting Australia with a greatly changed security environment. Three weeks after the decisive Japanese naval victory over Imperial Russia at the Battle of Tsushima, Australia’s Prime Minister, Alfred Deakin, ‘chief architect of her defence and foreign policy’, identified Japan as a ‘defence threat’ for the first time.3

Those concerns did not prevent London from renewing and expanding the alliance’s scope in mid-1905 and 1911. But as war with Germany loomed, the Australian Government did not embrace the prospect of Anglo-Japanese naval cooperation with enthusiasm:

When in an important speech on 17 March 1914 [then First Lord of the Admiralty] Winston Churchill asked for Australian and New Zealand Dreadnoughts to strengthen the decisive theatre in Europe, he based himself on the premise that Australia was adequately protected by the Anglo-Japanese alliance. Australian leaders, however, were flabbergasted by Churchill’s implication that the Pacific was to be made safe by the treaty with a nation whose people they did not admit to their shores.4

When the Great War broke out, ‘Australian apprehension that Japan would seize the opportunity to extend her empire further southward’ made London initially reluctant to call upon Japanese assistance.5 But the Royal Navy’s commitments to defeating the German High Seas Fleet in the North Sea, securing the Mediterranean and countering the U-Boat war in the northern Atlantic left little capacity for operations in the Pacific. Necessity won out, and the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) was asked to reduce the German fleet base at Tsingtao, in north-eastern China, and to hunt down the cruisers based there.

This period saw unprecedented levels of Japanese-Australian naval cooperation, an often cited example of which was the cruiser HIJMS Ibuki’s role escorting the first ANZAC troop convoy through the Indian Ocean in November 1914. Around the same time, the pre-dreadnought Hizen and the cruisers Asama and Izumo joined the battlecruiser HMAS Australia and the light cruiser HMS Newcastle off Mexico’s Pacific coast and headed south to search the Galapagos archipelago for the German Pacific Squadron cruisers.6 Beyond those examples, the IJN committed 12 cruiser sorties to southern patrols in Australian throughout the war’s duration,7 for which the Australian Government has been described as ‘less than enthusiastically grateful’.8

Competition

The limits of that cooperation quickly emerged, however, when it came to the occupation of Germany’s Pacific Ocean territories. By 24 September 1914, the hastily assembled Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force (AN&MEF) had secured most of German New Guinea, while a New Zealand force occupied German Samoa at the end of August. On 6 November, a half-company-sized force from the AN&MEF had occupied Nauru.9 At relatively low cost, these antipodean forces had secured the German territories south of the equator. But the AN&MEF expedition had been at the limits of Australia’s military and naval capabilities. Shortcomings in logistics, training and preparedness were masked by the light opposition put up by the small local paramilitary Polizeitruppe.

When the British Admiralty enquired whether Australian forces could occupy the more distant German North Pacific territories, the Army raised a third AN&MEF battalion-sized force, dubbed the ‘Tropical Force’, in November.10 The commitment of the available naval escorts, troopships and coal to the first ANZAC convoy from Australia delayed the Tropical Force’s availability.11

While the Australians tarried, the Japanese did not. Prompted by a request from the British Admiralty,12 but acting virtually independently of the Japanese Government, IJN landing parties seized the Mariana Islands (Saipan), Caroline Islands (Truk, Yap, Kusaie [now Kosrae], Ponape, Palau, Angaur) and Marshall Islands (Jaluit) in October 1914.13 Although the IJN proposed ‘permanent retention of all occupied islands’, the Japanese Government was not initially committed to their long-term possession.14 When Tokyo offered to hand Yap over, the Australian authorities were unable to find the necessary escorts for such a convoy, and cheekily enquired whether the IJN could provide that support.15 Tokyo’s position soon changed when domestic Japanese sentiment was aroused, and:

Riots emerged in Tokyo when it was learned that the government was prepared to hand over the Micronesian islands to their allies. The commotion caused the Japanese Government to retract its offer, and on 23 November, Britain asked Australia not to proceed to any islands north of the Equator.16

Anglo-Japanese cooperation was now transforming to become Japanese- Australian competition in the Pacific:

In these embarrassing circumstances the Commonwealth Government perceived a divided duty. On the one hand it did not wish to adopt a policy which would cause difficulties to the Imperial Government; on the other hand it considered that Australia had geographical and strategic claims to the occupancy of these islands, possession of which by any Power other than Great Britain would profoundly affect the trend of Australia’s naval defence policy in the future.17

A 3 December telegram from the British Government was even more conclusive:

… as Pelew, Mariana, Caroline Islands, and Marshall Islands are at present in military occupation by Japanese who are at our request engaged in policing waters Northern Pacific, we consider it most convenient for strategic reasons to allow them to remain in occupation for the present, leaving whole question of future to be settled at the end of war. We should be glad therefore if the Australian expedition would confine itself to occupation of German islands south of the equator.18

Thus the AN&MEF Tropical Force expedition, ‘which had been so completely fitted out that it even carried with it postage-stamps overprinted “N.W. Pacific,” came to an end before it sailed’.19

Confrontation

The end of the First World War and the peace initiatives that followed inadvertently increased Australian-Japanese cooperation. In 1919, Australia stridently opposed Japan’s Racial Equality Proposal at the Paris Peace Conference. Then in 1922 Japan was forced to return Tsingtao to the Republic of China, while the conclusion of the Washington Naval Treaty saw Britain annul the Anglo-Japanese treaty and decline to support Japan’s demand for closer naval parity with the Royal Navy and the US Navy.

The League of Nations—the forerunner to the modern United Nations— awarded Australia and Japan mandates over the former German Pacific territories. But that mandate required that these territories were not militarised, forbidding their fortification or the establishment of armed forces there. So in 1922 the Australian Army decommissioned the 6-inch coastal defence battery it had installed at Rabaul four years earlier, and avoided raising local militia forces when the garrison was withdrawn.20

From the early 1930s Japan was increasingly seen as an aggressor state. The League of Nations determined that Imperial Japanese Army officers had staged the 1931 Mukden Incident as a pretext for the invasion of north- eastern China, known as Manchuria. After the League of Nations General Assembly prepared to condemn Japan as an aggressor in February 1933, Tokyo gave formal notice of its withdrawal from the League. Similar incidents in Shanghai (1932) and later the 1937 Marco Polo Bridge Incident led to the Second Sino-Japanese War. Japan occupied Hainan in 1939 and then French Indochina in September 1940. In 1936, Japan also withdrew from the negotiations for a successor to the Washington Naval Treaty.

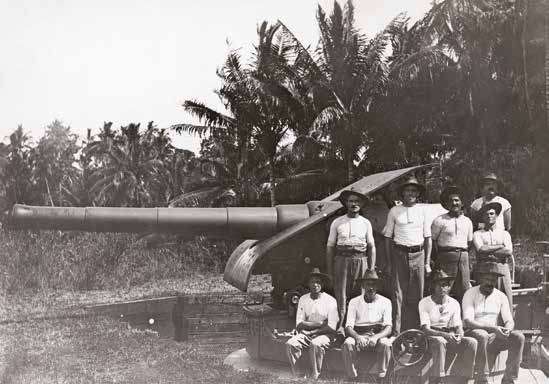

Rabaul, c. 1914. A krupp gun with a step swagged barrel. An Australian gun crew pose beside it (Image courtesy AWM H01986)

While successive Australian governments recognised the increasing Japanese threat, they did not invest in the capabilities needed for the Army to defend Australia’s northern approaches. That growing threat coincided with the Royal Navy’s further withdrawal from East Asia, starting with the closure of its forward naval base from Weihaiwei (near Tsingtao) in 1930. Under the emerging Singapore strategy, the Singapore ‘fortress’ would be defended until a Royal Navy fleet arrived to sally north to relieve or recapture Hong Kong and then blockade Japan to force Tokyo to accept terms.

Despite that strategy, the Australian Army focused its force planning on the establishment of a Second Australian Imperial Force (AIF) which, like the AIF of the First World War, would comprise infantry and light horse formations equipped to fight in Europe or the Middle East. At the same time, the Army confronted the block obsolescence of its artillery and small arms, a by- product of having relied for two decades on the surplus remaining from the First World War.

Scant regard was given to the emerging demands of modern warfare, let alone any requirement to fight in the South-East Asian or South-West Pacific littoral. Nowhere was this more evident than in the shortfalls of the weapons systems needed to defend against enemy air and naval forces. Nor did the Australian Army seek to exercise in the region to determine how and where best to deploy forces and sustain them in the unfamiliar South-East Asian and South-West Pacific regions. There was no meaningful engagement, let alone training, with regional US, French, Dutch or Portuguese forces. Nor did the Army realise the potential of indigenous forces such as those later raised in Papua and New Guinea.

Anti-aircraft guns were in especially short supply. By the end of 1940, only 40 3.7-inch anti-aircraft guns had been produced; by November 1941, that figure had reached 165 guns, ‘but without predictors’, which were not manufactured in Australia, ‘they were of limited value’.21 Modern 40 mm Bofors guns were requested from Great Britain, but production there could not meet British demands, let alone those of the rest of the Empire.

From 1934, Australia’s coastal defences were reinforced,22 including by the acquisition of 9.2-inch guns, which could outrange and outgun Japanese heavy cruisers that might raid key Australian ports. Those heavier weapons could not be spared for the northern approaches, however, and it was not until July 1939 that a 6-inch battery was installed at Port Moresby.23 Similarly, it was not until an infantry company from the 15th Battalion arrived in July 1940 that Papua New Guinea could claim to have even the most rudimentary garrison.24 A key factor that delayed the dispatch of these forces was the absence of the infrastructure needed to accommodate even a modest force.

To remediate these shortages, in October 1941 the Australian Government requested that the US Government provide, under the Lend-Lease program, weapons and equipment to thicken Australia’s coastal defences in the South-West Pacific. For example, the Australian Government planned to turn Base F—as Washington referred to Rabaul—into a forward base for a counter-offensive against the Japanese base at Truk. In October 1941, the US Government was requested to provide six 7-inch guns, eight 3-inch anti-aircraft guns, an anti-submarine harbour boom defence net and radio direction-finding equipment (i.e. radar).25 But, as events proved, these would not be ready in time for the Japanese attack. Even if they had been, more time would have been needed to train crews in their use.

Wartime conscription and a manpower shortage meant the potential of indigenous troops also received belated attention. Infantry battalions were gradually raised in Papua (from June 1940), the Torres Strait Islands (from May 1941), the Northern Territory (February 1942) and New Guinea (from March 1944). While these units proved effective, much time was needed for their establishment and training. It was not until mid-1942 that the Papuan Infantry Battalion participated in significant combat operations (whereas the Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion, the 2/1st North Australia Observer Unit and the Northern Territory Special Reconnaissance Unit did not see significant combat). Had these units been raised earlier, their contribution to the war might have been even greater.

Conflict

War with Germany highlighted the inadequacy of the Australian Army’s inter- war preparations. As in the First World War, Royal Australian Navy (RAN) ships, Army’s Second AIF divisions, and Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) combat squadrons were spread across the globe in defence of the Atlantic and the UK, the Mediterranean, the Middle East and the Indian Ocean.

This left few resources for the Pacific where, aside from the looming Japanese threat, German commerce raiders were active. In December 1940, the German armed merchant ships Komet and Orion sank five merchant ships around the Australian-administered island of Nauru and damaged the island’s phosphate-loading facilities. The most resistance shown was when Nauru’s Administrator, Frederick Chalmers, who had commanded the 27th Battalion in the First World War, ‘stormed along the sea-front shouting at the enemy’.26 Those raids demonstrated the vulnerability of Nauru and the nearby British-controlled, and similarly phosphate-rich, Ocean Island, both of which were important to the British Empire’s war economy.

Even had the British Empire’s navies and air forces not been heavily committed to operations across all theatres, land-based coastal defences represented an economical and effective way of defending these outer islands. But the decades of under-investment left the Army without adequate resources to protect Australian interests in the region. The Army planned to install a pair of 6-inch coastal defence guns on Nauru and a second pair on Ocean Island to deter further raids.27 All that could be spared, however, were two detachments (known as Wren Force and Heron Force) equipped with a pair of obsolete 18-pounder field guns each.28

As its strategic circumstances worsened, the Australia Government attempted its own last-minute diplomacy and reconsidered cooperation with—or at least appeasement of—Japan. Following what has been described as the ‘tiptoe policy’, the Menzies Government urged London to temporarily close the Burma Road in the summer of 1940 to appease Tokyo, while continuing exports of iron ore and other ‘war material’ to Japan.29 Australia’s first ambassador to Tokyo, Sir John Latham, even suggested that Australia offer to buy Japanese military aircraft, and ‘for a few months promising negotiations with Mitsubishi proceeded’.30

The die was cast in December 1941 when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and US bases in the Philippines. At the same time Japanese forces raided Singapore, invaded Malaya and sank the Royal Navy battleship Prince of Wales and battlecruiser Repulse, which had been deployed to Malaya to underpin the Singapore strategy. Those strikes were made possible by Japan’s possession of the former German Pacific territories. IJN bases in the Marshall Islands supported the attacks on Pearl Harbor, Wake Island, and later Nauru and Ocean Island; Palau supported the invasion of the Philippines; Saipan in the Marianas supported the invasion of Guam; and Truk—the IJN 4th Fleet’s home port since 1939—was the base for IJN amphibious landings at Rabaul and Kavieng in New Guinea.

Rabaul, New Britain. 13 September 1914. German civilian residents watching Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force (AN&MEF) troops marching through Rabaul as they take control of German New Guinea. (Image courtesy AWM, H12836)

The Australian Army too had deployed forces across the northern approaches. The AIF 8th Division—only one of four AIF divisions—and other AIF and militia units spanned a 7,500 km arc from Malaya, Singapore, Timor (Sparrow Force), Ambon (Gull Force), Port Moresby (30th Brigade), New Britain and New Ireland (Lark Force), Nauru (Wren Force) and Ocean Island (Heron Force).31 These latter forces constituted what was soon called an ‘advanced observation line’—a picket line that would maintain forward air bases for aerial reconnaissance.32

Sparrow, Gull and Lark forces were each based around an AIF infantry battalion, but they were not combined arms teams. Lark Force was the best equipped, with a coastal defence battery of two 6-inch guns and a pair of obsolete 3-inch anti-aircraft guns and an independent company— the Army’s first deployment of commandos. But even this force had been designed:

… to deal with the situation as prevailing in 1940–41, viz. fleeting bombardment raid by, at most, one or two armed merchantmen. The problem of air attack or sea bombardment on a Pacific War scale was not budgeted for since sufficient coast guns and anti-aircraft guns were not available for the more important main-land ports let alone Rabaul.’33

Thus, Lark Force—indeed all the ‘Bird Forces’—lacked field artillery and, even though there was a battery minus of anti-tank guns, the battalion’s Bren Gun Carriers constituted Lark Force’s only armoured vehicles.

The speed of Japan’s advance into South-East Asia and across the Pacific forced reconsideration of Army’s forward deployments. The Australian Government agreed to further reinforce the strategically vital Singapore ‘fortress’, but conceded that Wren and Heron forces were too weak to deter the IJN. They were withdrawn to Australia in February 1942, ceding Nauru and Ocean Island to uncontested Japanese occupation in August and allowing the IJN to extend its reach into the South Pacific and towards the vital US–Australia sea lanes.

In considering the fate of the remaining three Bird Forces, the Australian Government and Army hedged their bets. They agreed that US aid would not arrive in time but felt that, even if the Government was unable to reinforce these forces, they could not be abandoned. To have done so would have been to cede to the Japanese the harbours and airfields that lay across Australia’s northern approaches. These were needed both to protect Singapore’s eastern flank and for a future Allied counter-offensive into the North Pacific. Moreover, the Government was concerned lest the Bird Forces’ withdrawal discourage the Dutch from defending the Netherlands East Indies.34

This left the third option: for the garrisons to remain with only such reinforcements as could be spared in the time available. Not only were combat-ready troops unavailable but also the RAN’s commitments to other theatres meant that neither warships nor transports were available. In their stead, the Australian authorities despatched the meagre RAAF assets that could be found and deployed quickly. Unable to reinforce, and both unable and unwilling to withdraw, the three Bird Forces remained where they were. As the Chief of Naval Staff noted in a dispatch to the Australian Ambassador in Washington about Lark Force, ‘It is considered better to maintain Rabaul as an advanced air operational base, its present small garrison being regarded as hostages to fortune.’35

Isolated and incapable of supporting each other with the weapons available to them, the three garrisons suffered the same fate. Lark Force ceased to be a fighting force within hours of the Japanese landing at Rabaul on 23 January 1942. Gull Force surrendered on 3 February, and then Sparrow Force on 23 February.

Only the commandos were able to continue fighting. On East Timor, the 2/2nd Independent Company withdrew towards East Timor’s south coast and pursued a guerrilla campaign until the end of the year. Lark Force’s 1st Independent Company also performed its stay-behind role admirably, even after the loss of its headquarters at Kavieng, New Ireland, on 23 January. That company’s remaining detachments—fewer than three

platoons—maintained their surveillance outposts at key points along a nearly 3,000 km arc extending from Seeadler Harbour on Manus Island through Namatanai in central New Ireland, Buka Passage in Bougainville, Tulagi in the Central Solomons, and Port Vila in Vanuatu. From those outposts, the commandos undertook presence and reconnaissance patrols, established observation posts, and supported the RAN Coastwatchers network, laying the foundations for their M Special Unit successors. Last to withdraw were the commandos at Tulagi, who supported the RAAF seaplane and wireless base there until the eve of the IJN’s 3 May 1942 invasion which triggered the Guadalcanal campaign.

More than 2,000 Lark, Sparrow and Gull Force soldiers were killed or died in Japanese captivity. In the counter-offensives that followed, US forces

bypassed Timor, Ambon and Rabaul as they took the shortest road to Tokyo, but other locations such as Tulagi, Saipan, Palau and Kwajalein had to be retaken from the Japanese at great cost. Moreover, had the German Pacific territories not been ceded to Japan in 1914, the IJN’s opening offensives of the Pacific War would have necessarily been changed in scope and reach.

Conclusion

In the first two decades that followed Federation, Australia’s security relationship with Japan transitioned from awkward cooperation to an emerging competition. Upon the First World War’s outbreak, Australia found itself reliant on maritime security from the country it identified as the most direct threat to national security. That reliance both underscored and masked the limits of protection the Royal Navy could provide Australia in the event of a major conflict. In 1914, it was the limits of that indigenous naval force that forced the Australian Government to cede control of the central Pacific to Japan. Australia had the troops, but not the naval transports and escorts needed to occupy Imperial Germany’s North Pacific territories north of the equator.

Babiang, New Guinea, 1944. The speed of Japan’s advance into south-east asia and across the Pacific forced reconsideration of Army’s forward deployments. (Image courtesy AWM, 083056)

The First World War’s ashes had barely settled before Australia’s cooperative security relationship with Japan further transitioned through competition into confrontation. But Australia did not use the inter-war period to prepare for littoral warfare in South-East Asia and the Pacific. Saddled with war debt and in the face of the Great Depression, successive governments under- invested in defence, including the land-based air and sea defences that could have added substance to the advanced observation line established across South-East Asia and the South-West Pacific. Nor did the Army engage with prospective regional partners to offset its weaknesses, instead trusting that its traditional place in the British Empire provided the security guarantees needed. And, adhering to the conditions of the League of Nations mandate until the mid-1940s, nor did Australia raise local militia forces in the former German New Guinea, let alone indigenous ones.

As Washington had recognised, the advanced observation line included naval and air bases needed for a future counter-offensive against Japan. Properly defended, bases like Rabaul threated the IJN’s forward bases in the former German Pacific territories, but in their largely indefensible state the Australian bases were vulnerable to attacks from those Japanese bases. Land-based forces were needed to provide the persistent defence of these bases to allow naval and air forces to concentrate where they were most needed. Those land forces needed to be composed of combined arms, equipped with anti-aircraft and coastal defence artillery to contest the airspace and waters around them. When the Government belatedly recognised those needs, the required weapons were in short supply and not available in the time frames needed. Without them, the fates of the Army units deployed to cover Australia’s northern approaches were left to fortune.

The Australian Army faces many of these challenges today. Advances in transportation, weapons and communications technologies have eroded the security buffer once provided by the Pacific Ocean’s vastness. Regional powers vie for and fortify contested reefs and islands as naval powers compete for control of the Western Pacific.

Accelerated Warfare describes these challenges and the need for partnering, cooperation and jointness to mitigate these security challenges. Increasingly the Australian Defence Force has the joint capabilities needed to transport, protect and sustain land-based task groups at such remote locations, and to contest control of the air and sea around them. Moreover Army, as part of that joint force, has strengthened engagement with regional and non- traditional partners. In addition to building partner force capacity across the region, Army has invested in indigenous and special forces for the domestic and overseas regional surveillance and reconnaissance roles.

At the same time, Army is replacing or upgrading the armoured component of its combined-arms capability, and has announced surface-to-air missile upgrades that now extend engagement ranges beyond those attained in the pre-missile era. Army is also examining long-range fire options that could replace the coastal defence capability disbanded in 1962. Such changes provide Australia with the capability not only to contest its northern approaches before cooperation, competition and confrontation transition into conflict but also to deter such an escalation in the first place.

Endnotes

- Chief of Army, 2018, Futures Statement: Accelerated Warfare, 2018 (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia).

- HP Frei, 1991, Japan’s Southward Advance and Australia, (Carlton, VIC: Melbourne University Press), 83.

- Frei, 1991, 84.

- Frei, 1991, 89.

- Royal Navy Naval Staff, 1922, Naval Staff Monographs (Historical), Volume V: The Eastern Squadrons, 1914 (London), 46.

- Royal Navy Naval Staff, 1922, 121, 166.

- In addition to Ibuki, the light cruisers Chikuma and Yahagi cruised off Northern Queensland between December 1914 and January 1915. In April 1915 the cruiser Nisshin visited Rabaul and Madang, while between May and July the training ships Aso and Soya visited Australian ports between Fremantle and Rabaul. In May–July 1916 the Azuma and Iwate did the same between Fremantle and Brisbane. In March 1917 three IJN cruisers and eight destroyers escorted troopships (none Australian) through the Indian Ocean. Between May and June 1917 the cruisers Izumo, Nisshin, and Kasuga escorted cargo vessels between Fremantle and Colombo. For most of 1917 the light cruiser Hirado and her sister-ship Chikuma were in or near Australian waters until November and December respectively. The cruisers Nisshin, Kasuga and Yahagi also patrolled the Western Australian coast at intervals during 1917. The light cruiser Yahagi visited Fremantle in March 1917, and in May– October assisted Australian ships in patrolling the north-eastern coasts of the continent and the islands northwards. Also from mid-August to the beginning of October the cruiser Nisshin patrolled off Fremantle. AW Jose, 1941, The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918, Volume IX—The Royal Australian Navy: 1914–1918 (Sydney: Angus and Robertson), 340–341.

- P Dennis, J Grey, E Morris and R Prior, 1995, The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History (Melbourne: Oxford University Press), 322.

- SS Mackenzie, 1941, Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918, Volume X—The Australians at Rabaul: The Capture and Administration of the German Possessions in the Southern Pacific (Canberra: Australian War Memorial), 143–144. In August, New Zealand’s Samoa Expeditionary Force—escorted by the RAN squadron —had captured German Samoa unopposed.

- Mackenzie, 1941, 153.

- Mackenzie, 1941, 153; Jose, 1941, 133–134.

- J Corbett, 1920, Official History of the War, Naval Operations, Volume 1: The Battle of the Falklands, December 1914, (London: Longmans, Green and Co), 305.

- Kaigun Hōjutsushi Kankōkai, 1975, Kaigun Hōjutsushi (Navy Gunnery Branch History), (Tokyo: Kaigun Hōjutsushi Kankōkai), 495.

- IH Nish, 1972, Alliance in Decline: A Study in Anglo-Japanese Relations, 1908–23, (London: University of London, Athlone Press), 144.

- Frei, 1991, 96.

- Frei, 1991, 97.

- Mackenzie, 1941, 159.

- Mackenzie, 1941, 160.

- Jose, 1941, 136–137.

- National Archives of Australia, MP1049/1, 1919/0137, Maintenance of Rabaul as a Defended Port, folio 26, Cablegram from Secretary, Department of Defence, to Administrator Rabaul, dated 28 September 1918. Article XIX of the Washington Naval Treaty also prohibited Britain (and therefore Australia), Japan, and the United States from constructing fortifications or naval bases in the Pacific Ocean.

- DM Horner, 1995, The Gunners: A History of Australian Artillery (Sydney: Allen & Unwin), 224, 237.

- Horner, 1995, 203.

- Horner, 1995, 207.

- F Cranston, 1983, Always Faithful: The History of the 49th Battalion (Brisbane: Boolarong Publications), 100. By October, this force of one Vickers machine gun platoon and three rifle platoons had been re-designated as the, in anticipation of being joined by soldiers from that battalion.

- National Archives of Australia, A1196, Chief of Air Staff 15/501/207 File, Rabaul—Local defences, Record of Discussion in Naval Boardroom on Tuesday 28 October 1941 between the Chief of Naval Staff, Chief of the General Staff, Deputy Chief of Naval Staff, Director Plans, Lieutenant Colonel Nurse, and the Assistant Director Plans.

- Kerry F Keneally, 1979, ‘Chalmers, Frederick Royden (1881–1943)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography (National Centre of Biography, Australian National University), at: http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/chalmers-frederick-royden-5546/text9453

- Horner, 1995, 232.

- Initially known as Wren Force and Heron Force, these detachments from the 2/13th Army Field Artillery Regiment were later renamed (in August 1941) as Nauru Force and Ocean Island Force respectively. Australian War Memorial, AWM52, 1/5/60, Wren Force Nauru; AWM52, 1/5/47, H Force and Ocean Island Force.

- P Hasluck, 1952, Australia in the War of 1939–1945, Series 4—Civil, Volume I: The Government and the People 1939–1941 (Canberra: Australian War Memorial), 228.

- G Blainey, 1971, The Causes of War (New York: Simon & Schuster), 247.

- Blackforce—built around the Australian 2/3rd Machine Gun Battalion and the 2/2nd Pioneer Battalion—was sent to Java in February 1942.

- L Wigmore, 1968, Australia in the War of 1939–1945, Series 1—Army, Volume IV: The Japanese Thrust (Canberra: Australian War Memorial), 396.

- FN Nurse, 1965, ‘Praed Point Battery, Rabaul’, Australian Army Journal no. 195: 38–45, 41. Colonel Nurse was responsible for the siting of the ‘Rabaul Fortress’ guns.

- Wigmore, 1968, 396.

- National Archives of Australia, A1196, Chief of Air Staff 15/501/207, Cablegram No. 152 from Chief of Naval Staff to to Australian Minister (Ambassador) Washington, dated 12 December 1941.