Abstract

Operational contracting is a common yet contentious component of military operations. The Australian Army recognises the role of contractors and has, to a degree, incorporated contractor services into its operational cycle. Although contractors are positioned to provide flexibility, responsiveness and cost-effectiveness to military operations, problems persist. The core conundrum is whether the use of contractors becomes either an expression of commercial capability or commercial dependency. Parallel to this problem, is how best to manage, integrate and sustain contractor support throughout the operational cycle. To explore this further, this article will examine the concept of Operational Contract Support (OCS), a United States (US) developed capability platform, leveraged to overcome past contractor challenges, which integrates, manages and supports contractor usage throughout all levels and phases of a military operation. Examining contractor roles in the Australian Army aligns with higher-order government intent, enunciated primarily in the 2016 White Paper on Defence. The White Paper called for a deeper military relationship with the US and recognised contractors as contributory elements for an organisationally robust and agile ADF. For Army, this means that a closer relationship with the US military necessitates a careful appreciation of how the US employs contractors, now and in the future. Crucially, by examining OCS, Army can use lessons learned from the US in its own future planning for how, where and when contractors are best operationally employed.

Without being commercially capable, Army risks a sub-optimal performance on operations –

- Brigadier David Saul, Australian Army Journal, 20072

Introduction

Commercial contracting for military operations is not a new practice for the ADF. The large mobilisations of the First World War witnessed Australia making use of civilian-crewed merchant ships to transport supplies and soldiers. More recently, the private sector provided operational support to ADF (and AFP) deployments in East Timor, the Solomon Islands, the Sudan, Iraq and Afghanistan. To this end, the ADF has mirrored the choice taken by many other militaries to outsource Defence functions in areas such as logistics (air and sea transport, rotary wing support), base maintenance, laundry services, fleet management and medical services.3 These instances of commercial support to operations have drawn comment and analysis,4 but they have not generated such polarised debate as US contracting practices have. Primarily, this is because Australia has approached the issue of privatising Defence functions very cautiously, and with good reason, given the past contractor challenges experienced by the US. Although Australia has awarded quite a few contracts for hardware procurement5 and outsourced many non-core Defence functions to the private sector, very little in the way of replacing soldiers with contractors on the battlefield has occurred. Core Defence functions are therefore only carried out by organic force capabilities.

While this balance between core and non-core is essential, the ADF is not just a blunt military instrument. Its core function remains the defence of Australia from armed attack, yet second and third order tasks span an increasingly growing spectrum. The growing spectrum of mission types – from Humanitarian Assistance to Disaster Relief6- engenders more complex logistic requirements which in turn exert pressure on organic capacities to sustain the larger logistic footprint. Coupled with the broader mission parameters is the planned growth of the ADF workforce to about 62,400 over the next decade.7 More people require more support be it before, during, or in the transition from military operations to civilian administration. Underpinning these organisational growth spurts is the external strategic environment facing Australia and its attendant impact on how the ADF is best structured, positioned, equipped and trained. It is at this juncture that current operational contracting in Defence has assisted the ADF in meeting its multiple hybrid tasks. Australia’s defence relationship with the private sector is thus balanced between the need for maintaining economically efficient (and reliable) partnerships in a time of strategic complexity and preserving the delicate legal and organisational equilibrium of how, when and where contractors should be employed.

So, where does Army fit into this organisational picture and what model can Army consider for future operational contract support? This question will be addressed as follows: firstly, the article will examine the joint Operational Contractor Support (OCS) model now employed by the US. It will describe the conceptual history of OCS and its current institutional and organisational status in the US Department of Defense (DoD). Secondly, and drawing on this analysis, the article will distil the challenges of OCS, and how the identification of these challenges may augment Army’s future considerations for employing contractors during operations. The discussion of OCS as it relates to Army will be driven by two crucial determinants. The first is whether OCS may create commercial dependency instead of commercial capability within Army. The second is concerned with what operational value Army could derive from OCS.

Conceptual Heritage of Operational Contract Support

From a global perspective, various OCS models are currently being utilised by numerous militaries during deployed operations. These include the US, Canada and the United Kingdom (UK). The European Union (EU)8 has also explored the concept of employing civilians to augment and sustain its deployed military forces. The employment of civilians external to the civilian military workforce to support military operations, which is the key conceptual demarcation of OCS,9 is neither a new phenomenon nor is it revolutionary in terms of how warfare has been prosecuted.

The US has, since 2008, led this trend to develop a stable and reliable platform which supports operational sustainment via a large contractible, commercially orientated civilian workforce. The need for a dependable and cohesive contracted civilian workforce has emerged out of battlespace, security and legal realities which have confronted the US military in recent times. The most prominent and widely discussed of these realities is the fraud, wastage and mismanagement of contracts during operations in Iraq and Afghanistan.10 Another key challenge emerged within the combat and operational sphere. For the uniformed forces, coalition partners and various governmental agencies making use of contractors in support of combat operations, the lack of integration and coordination with both broader strategic objectives and lower-level tactical milestones greatly affected unity of effort, morale, and challenged the security of deployed military and civilian/military units.11 It further undermined the legitimacy of missions and hampered the transition from military to civilian administration. These realities drove the need to explore how an integrated, coordinated strategy of OCS could be implemented across all arms of service.

In 2010, The US DoD produced a Concept of Operations (CONOPS) for OCS. This document defined OCS as, “The ability to orchestrate and synchronize the provision of integrated contract support and management of contractor personnel providing that support in a designated operational area”.12 The two pivotal aspects of OCS, Contract Support Integration (CSI) and Contractor Management (CM), were discussed in depth and seen as critical enabling components for seamless and synchronised OCS employment to uniformed forces. The CONOPS for contractor support was driven by important assumptions relating to the future of contractor usage by the DoD, other governmental departments, and US multinational partners. Important core assumptions included the following,13

- Contractors will continue to be a decisive component of the Total Force.14

- Commercial support to contingency operations will remain a feasible and cost- effective option.

- Effective and proficient management of OCS will continue to be a strategic priority.

- The employment of US military forces will continue as part of the ongoing commitment to coalition forces. There is recognition that these coalition partners will require significant joint force-provided contract support.

- The support and management processes provided to contractors will be deployable.

These core assumptions formed the bedrock for positioning integration and coordination as paramount features to the success of OCS as a reliable, sustainable and responsive platform for the US DoD. The primary purpose of the CONOPS paper was to present a clear vision and pathway of OCS in the US DoD until 2016. This vision would then cascade into the US DoD’s, capability development system which assess OCS against the following factors: doctrine, organisation, training, materiel, leader development and education, personnel and facilities (DOTMLPF). The CONOPS for OCS described contractor support as, “a powerful force multiplier that can provide services that are not viable for execution by military forces or are performed more effectively or efficiently by contract solutions”.15 OCS, as described in the CONOPS was structured to be applicable across all four of the command echelons within the US DoD. These command echelons were drawn from the identified levels of war (LOW); strategic, operational and tactical. In addition to placing OCS as a key component to US force sustainment in all LOW, the CONOPS positioned OCS as a response to various key federal sources of strategic guidance. This linked OCS with higher-order government intent relating to how the US DoD sustains and supports its deployed forces. Important sources guiding the development of CONOPS for OCS included,

- The 2006 Quadrennial Defence Review (QDR);

- The 2008 National Defence Strategy; and

- The 2009 Capstone Concept of Joint Operations (CCJO).

The level of integration and coordination described in the CONOPS for OCS is illustrative of key realties relating to how the US utilises contractors as part of its Total Force concept. These realities can be unpacked (not exhaustively) as the following,

- Contractor support (irrespective of scale, scope or service-type) is now an expected component of the force sustainment for the US across all arms of service and between various governmental departments and multinational partners.

- Uncoordinated and poorly planned integration of contractors is a strategic, operational and tactical liability. Sustainable Command and Control (C1), based on coordination and integration of OCS, is a force multiplier.

- Contractor support needs to be planned for throughout the various operational planning and execution phases. This ensures that unity of effort is not eroded, fraud and wastage are minimised and the appropriate legal mechanisms are addressed regarding the role and purpose of civilians in an operational area.

- OCS is considered to be a critical capability to the success of all US operations, be they unilateral or multilateral in nature. By virtue of its important role, OCS requires robust institutional integration within the US DoD in order for this capability to render its intended effective, responsive and efficient use in the future.

- The CONOPS for OCS is a blueprint depicting full contractor integration in US joint operations. As a blueprint, it sets out the organisational concept of OCS as an appropriately robust, integrated, comprehensive and resourced support platform for all future US joint operations.

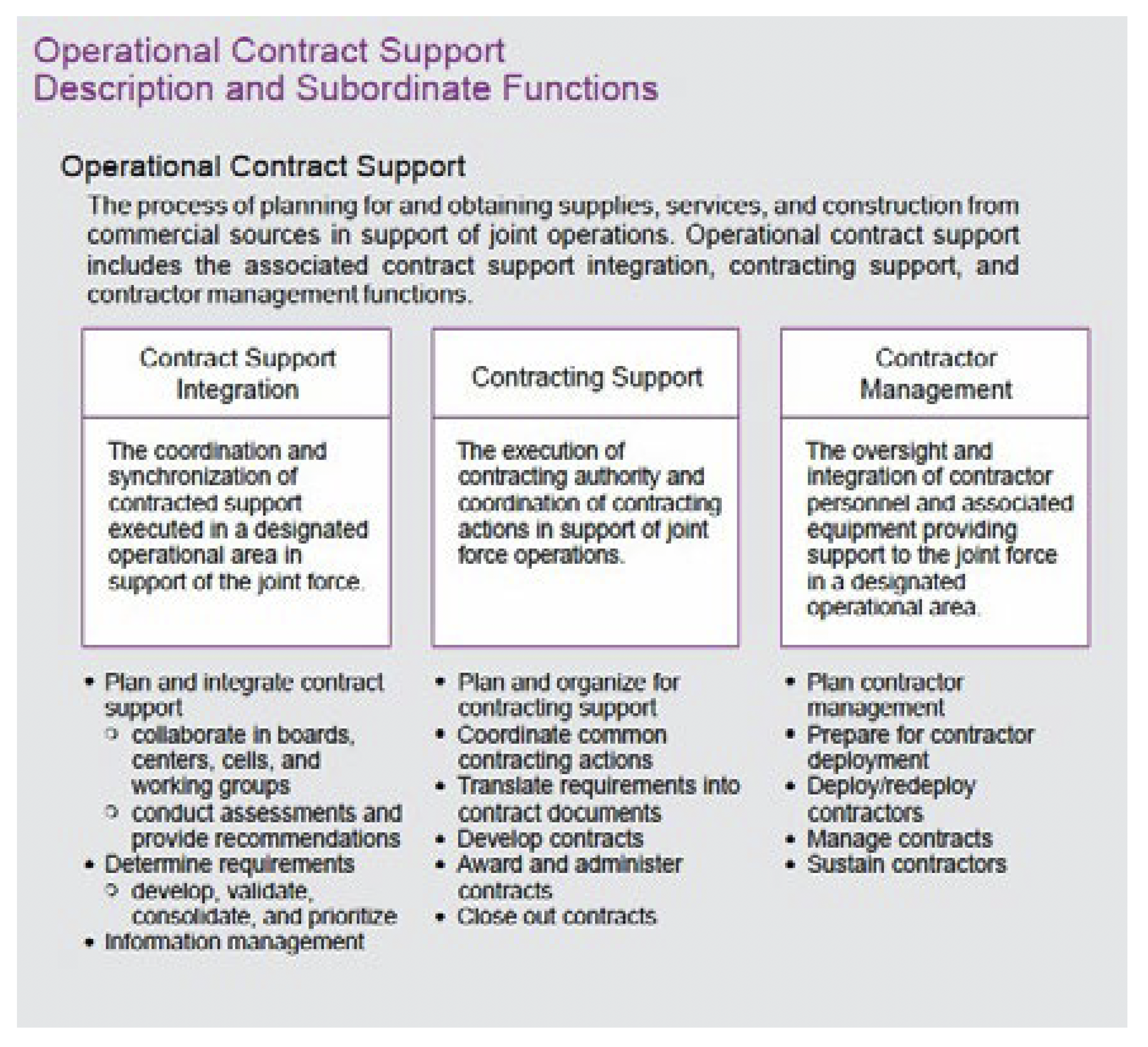

In 2013, the US DoD released Operational Contract Support Joint Concept16 which enlarged on the strategic need for a joint approach to OCS throughout all arms of service. In 2014, Joint Publication 4-10, Operational Contractor Support was released and can be regarded as the culmination of current OCS thinking in the US DoD. This document describes doctrine for the planning, execution and management of OCS in all phases related to US joint operations. In essence JP 4-10 is a document solely concerned with joint-arms operational sustainment. This focus feeds into the unofficial motto of, “You cannot spell sustainment without OCS”.17 JP 4-10 characterises its approach to OCS as functional and programmatic. The functional aspect denotes linking services with particular capability requirements of the mission, and the programmatic approach is a reference to the need for Joint Force Commanders (JFC) to, “fully consider cost, performance, schedule and contract oversight requirements as well as many other contract-support related matters (e.g., risk of contractor failure to perform, civil- military impact, operations security)”.18 As a doctrinal document, JP 4-10 incorporates the entirety of the CONOPS for OCS and expands on various themes presented and discussed in the CONOPS. JP 4-10 therefore describes OCS as, “the process of planning for and obtaining supplies, services and construction from commercial sources in support of joint operations”.19 This definition has its heritage in the Operational Contract Support Joint Concept which aligned OCS with the overriding joint nature of US military operations. Additionally, JP 4-10 distributes OCS into three (not two as the CONOPS had originally) functional areas: contract integration support, contracting support and contractor management.

Critically, JP 4-10 divides the force protection (FP) of contractors between, “the contractor and the United States Government”.20 It goes on to state that FP responsibility for contractors in permissive environments may only receive partial support from the Geographical Combat Commander (GCC) and the Joint Force Commander (JFC). In this low-level threat environment, contractors are largely responsible for planning, managing and executing their own FP. In hostile environments, JP 4-10 acknowledges the operational and tactical difficulties experienced by the JFC in supplying adequate FP to contractors.

JP 4-10 primarily stresses the jointness of OCS as a key enabler for effective contractor usage. The principle of jointness is reinforced by a Joint Lessons Learned Information System (JLLIS) platform for all arms of service. The role of JLLIS is to aggregate and store a system of record from all arms of service utilising OCS. The Joint Lessons Learned Program, (JLLP) which facilitates the JLLIS, is further responsible for coordinating input from the various arms of service on issues of OCS and possible solutions that have been suggested to mitigate these challenges.21 The envisaged goal of JLLP therefore is to distil lessons learned of OCS from a joint capability perspective and channel these lessons into future doctrine and Tactics, Training and Procedures (TTPs) across all arms of service.

Figure 1: Diagrammatic representation of OCS as per JP 4-1022

In sum, JP 4-10 sets out in comprehensive detail current OCS practice in the US DoD. The overarching focus on jointness is structured to be the turnkey solution for efficient and effective management of contractors. As per figure 1, JP 4-10 attempts to aggregate approximately 11 years of lessons learned from OCS into a cohesive, systematic organisational construct which is responsive to the fluid operational demands experienced by US Forces. Its twin characteristics of being programmatic and functional seek to ameliorate challenges brought about by contractors in or near the battlefield. These characteristics also aim to link capacities of OCS with constantly evolving requirements expressed by the various arms of service. Yet, as with many evolving platforms, issues abound.

The following section will therefore pinpoint key challenges of OCS identified as being the most applicable for Army’s consideration of future contractor management and utilisation as per its operational requirements. These challenges will be divided into two categories. The first is conceptual, which will describe issues related to the OCS system which organises, integrates and manages contractors. The second category is best expressed as a structural challenge. Each category and its associated challenges will be channelled into a ’so what?’ question for Army. In this format, OCS can be examined against the Army’s future operational needs as determined by its known external environment.

OCS Challenges

JP 4-10 notes that, “There are few areas more uncertain than planning for use of commercially provided services in support of joint operations”.23 When one considers the size of the US armed forces, the complexity of its tasks which span a broad spectrum of missions, and the long tail of support functions needed to sustain a technologically networked organisation, this observation cannot easily be dismissed. The past challenges of contractor usage in operations are testimony to the enormous organisational and policy difficulties inherent in employing civilians on or near battlefields. Despite this, the CONOPS for OCS and JP 4-10 represent an important step forward in the attempt to seamlessly link contractor support with changing operational needs. This is because these documents illustrate a clear codification, which has previously not been attempted, of how, when, where and to what extent operational contracting is integrated, planned for and managed, especially in the realm of joint operations. The codification also allows for a systematic identification of challenges related to OCS in general. In effect, the codification of OCS into a cohesive policy document such as JP 4-10 creates a nodal point for future thinking of how contractor employment for joint military operations is best implemented.

Conceptual Challenges

Challenge 1: OCS is not a one-size fits all concept. As JP 4-10 observes, different planning cycles will apply in respect of systems support contracts (such as new weapon systems/platforms), theatre support contracts (logistics, security, medical, administrative) and external contract support (interpreters).24 Conceivably, these three categories of contract support may all be active within an area of operation, albeit at different times and depending on the overall footprint of the mission and its objectives.

Planning, managing and integrating the outcomes of these various contract types places a burden on the operational cycle and may further dislodge, due to a lack of adequate resources, unity of effort.

Outcome for Army

Under this challenge, Army’s Adaptive Campaigning- Future Land Operating Concept (AC- FLOC) could steer the course of how joint OCS may provide added operational flexibility and responsiveness to deployed Army elements. The AC-FLOC observes that, “The Land Force will be optimised for joint operations, operating in a joint environment, and relying on joint enabling capabilities for full effect. The Land Force is also required to be trained, equipped and resourced for effective interaction with Coalition partners and commercial contractors where applicable”.25 As a capstone document, AC-FLOC illustrates clear performance-based requirements for Army in a joint environment and outlines a common framework for how these requirements should be met. This cohesive framework forms a stable conceptual starting point for a deeper examination of contractor roles, particularly in supporting AC-FLOC five lines of operations. Given the overriding characteristic of ‘Jointry’ in the AC-FLOC, JP 4-10 can provide meaningful conceptual input for Army relating to the complexity of harnessing OCS to support joint operations. For example, joint forces may require various types of contractor support which may be utilised at different phases of the operation. JP 4-10 recommends that, “Key to success in the contractor management challenge is…to establish clear, enforceable, and well understood theatre entrance, accountability, FP and general contractor personnel management policies and procedures early in the planning stages for a [joint] military operation”.26

Other key inputs available for Army can be found in the US Army’s Training, Tactics and Procedures publication for OCS.27 ATTP 4-10 characterises OCS as “commercial augmentation” to existing organic capabilities. Crucially, ATTP 4-10 applies OCS in its intended joint model and provides recommendation to its commanders and their subordinates on how best to plan for, manage and sustain contracts during operations. A key capability enunciated by the US Army for OCS was the maintenance of effective deployable management cells to oversee and assist commander with contract support during the full operational cycle. For Army, this capability has already been recommended by the ASPI report on contractors in 2005, and later by Brigadier David Saul in his 2008 article for the Army Journal entitled, “Hardened, Networked…and commercially capable: Army and contractor support on operations”. Deployable contract management remains, as noted by Brigadier Saul, a critical enabler for effective contract management.

Challenge 2: In terms of joint force operations, OCS does not display a deep doctrinal history in relation to organically derived forms of joint force support. Essentially, the relationship between OCS and the concept of joint operations is very new. As with any new organisational relationship in the military, growing pains relating to the establishment of synchronicity between what is required and how those requirements are met can be challenging. JP 4-10 recognises this key challenge by noting that joint planning underpinned by comprehensive OCS is a significant departure from historical experience. For hierarchical clarity, and as it relates to the Australian Army, the identified challenges of OCS support to joint operations as per JP 4-10 are listed as follows,

- First Order challenge: A lack of adequate preparatory and continuation training modules for OCS as it relates to joint force support.

- Second Order challenge: A dissonance between the rapid evolution of techniques for OCS and capturing these developments in doctrine.

- Third Order challenge: Partial integration of planned OCS footprint into intelligence preparation prior to a joint deployment.

- Fourth Order challenge: Underdeveloped/immature systems of information collection relating to OCS activities in the area of operations.

Outcome for Army

The joint approach is a pivotal concept for Army, as AC-FLOC illustrates, and underscores what OCS is now structured for. Joint operations are by their very nature complex and attaching OCS to deployed units, even elements which form part of modular forces, can be challenging in terms of management and integration. A key challenge identified by JP 4-10 was the general lack of adequate training for uniformed personnel in how best to navigate contract planning, management and integration in joint environments. For Army, and taking note of these challenges listed by JP 4-10, it is imperative that OCS training models be understood within the broader concept of joint force support. The availability (and applicability) of modules for educating personnel on the joint nature of OCS is reliant on continuous training and assessment for educators tasked with teaching contractor management. Not only must educational modules be available to prospective personnel tasked with managing and integrating OCS, they must also be housed in systems that are appropriately responsive to changing techniques for OCS. The responsiveness of learning systems is dependent on, inter alia, the ability for change/development to be translated in a consistent, clear and efficient manner as it pertains to doctrinal or TTP updates. A dissonance between evolving OCS practices and updates to doctrine and TTPs may pose significant challenges to the management of OCS. Crucially it could erode the synchronicity needed between OCS and military force structures. This dislocation will impact the ability of OCS to function as an important force multiplier for Army.

Integrating OCS into pre-deployment intelligence planning makes practical sense, particularly if the operational environment is deemed hostile. Integrating OCS at the initial planning stage of joint operations may better manage risk to the contracted workforce by selecting and linking resources needed to protect it as part of overall FP. This is dependent nonetheless on the commander’s objectives, the resources available to fulfil the objectives and the nature of threats in or near the area of operations. Naturally though, enlarging the intelligence planning process to incorporate selected elements of OCS carries with it operational security risks.

Challenge 3: Using contractors in relatively benign or hostile operational environments carries attendant operational risks that must be planned for and managed by the relevant command structures and contracting organisations. At the core of this challenge is the impact contracting exerts on the military principle of command. Therefore, a common question posed when assessing the nature of contracted support is, “What operational value will the commander gain from contractors providing services in support of mission objectives?”. In terms of JP 4-10, it makes the following observation; “In all operations, contracted support is a joint force multiplier to some degree. When properly planned [and resourced] OCS can provide… enhanced operational flexibility and rapid increases in support force capabilities”.28 Crucially this result must be predicated on a mature and robust contractor support system which interacts well with its designated, and appropriately conditioned, military counter-parts. It is within this sphere of interaction that the twin issues of command and operational value should be determined for Army.

Structural Challenges

The structural challenge is no less crucial than the conceptual problems mentioned when determining the viability of larger contractor footprints in operations. A larger, more integrated contractor capability will necessitate a degree of structural change in a defence organisation. Structural change in large organisations such as Defence does not happen quickly and the transition period can generate substantial obstacles in respect of getting the job done in a manner consistent with its organisational values, beliefs and responsibilities. Of key concern is the issue of commercial dependability superseding organic capability. Importantly, this concern is determined by the scope of a military’s defence tasks assigned by government, the existing organic capabilities available for forces to execute these tasks, and the resources (defence budget) needed to sustain organic capabilities. In short, ends, ways and means will ultimately inform how the concern of commercial dependency with respect to commercial capability is addressed at a national strategic level.

Challenge 4: Could the use of contractors become an expression of commercial dependency? At the heart of this question is the scale and scope of contractor support that is required and the way it is planned for and delivered. This is determined by several considerations. First and foremost, and drawing from government higher-order intent, to what extent are contractors allied with defence tasks? Secondly, what functions are they expected to perform and are these mission-critical functions? Thirdly, are contractors the most suitable agents for the tasks given to them? Finally, most militaries of developed states are either fully networked or rely heavily on technology to gain combat supremacy over their adversaries. Large portions of this technology are developed by defence industry. Often there is a large contractor footprint (not necessarily in an area of operations) needed to assist uniformed forces apply, maintain and adjust the technology to the needs of the particular arm of service. JP 4-10 does not explicitly deal with this issue; however, JP 4-10 is illustrative of the deep structural and now dependent relationship between contractors and US forces. In this vein, JP 4-10 has a clear genealogy that reaches back to the following statement made in 2003 by Lieutenant General David Mckieman, Commander of the Third Army. He said, “A lot of what we have done in terms of reducing the size of active and reserve component force structure means there is a greater reliance on contractors. And there’s a lot of technology that requires contractor support”.29

Army recognises that a greater reliance on technology, and the constantly evolving need for assessing the appropriateness of existing technological platforms requires a larger contract support base. Maintaining or developing appropriate organic levels of technological expertise that can keep pace with Defence industry development is not a cost-effective approach. As the 2016 White Paper counselled, establishing a closer relationship with the Defence industry, and inviting industry to earlier planning stages for capability requirements, enhances the collaborative approach for sharing responsibilities in managing strategic risk.30

Outcome for Army

For Army, the concern of whether a larger contractor footprint may lead towards greater commercial dependency depends on the intended nature of contract support and its scope and scale in relation to mission parameters. As to the nature of contract support, higher-order direction is clear on the issue that contractors are components of an agile, responsive and resilient Army. Moreover, contractors are allied to Army tasks as force multipliers when the need arises. Key direction comes from,

- The 2016 Defence White Paper which listed contractors as a component for a more agile Defence Force.31 Additionally, the White Paper enunciated a higher-order intent from government for the ADF to deepen its existing close security relationship with the US and continue its current trajectory of pursuing interoperability and military integration with US forces. Conceivably, these aspects of the 2016 White Paper indicate that the size of contractor footprints in operations may grow across all arms of service. Army, with an expected growth of 8.6% may therefore see more contractors supporting Army in a variety of sustainment roles.

- The April 2014 Army Modernisation Update refers to contractors being part of Australia’s ‘Total Force’ concept.32 Closely aligned with Australia’s concept of ‘Total Force’ is the US concept of ‘Total Force’ which has incorporated contractors within its definition since as early as 2006. The concept similarity indicates structural similarities with the US in positioning contractors as important sustainment elements of landward forces.

- Adaptive Campaigning: Army’s Future Land Operating Concept (AC-AFLOC) refers to Australia’s land force requiring the training and equipment for, “effective interaction with Coalition partners and commercial contractors where applicable”.33

- Land Warfare Doctrine 1: The Fundamentals of Land Power (2014) noted that the Army is “not employed in isolation…Warfighting demands optimal force integration or ‘joint interdependence’… This is further enhanced by cooperation between the joint team and other government agencies such as police, diplomatic staff, legal representatives, private sector and non-government organisations”.34

The scale and scope of contractor support to Army will be determined, among others, by the mission requirements and operational realities; Intrinsic to this, is the requirement for Army to determine if ‘On occurrence support’ (OOC) or ‘Prearranged support’(PAS) best suits the realities and complexities of joint force sustainment. From the US perspective, OCS is planned for and visible throughout the joint operational cycle. The US recognises that its coalition partners may need significant contractor derived support. Determining this once the joint operation has commenced places unnecessary stress on managing force requirements for contractor services. For Army, PAS represents a comprehensive format for planning, integrating and managing contractors and has been recommended to the ADF as the optimal form of OCS.35 Capabilities and policy direction to support this model are present in Joint Land Command (JLC). As a prearranged package, OCS could bolster the structural need for agility and responsiveness in Army by integrating contractor support during planning phases of the operation. This would mitigate possible coordination problems between uniformed and contractor personnel once the operation commences. A strong argument can be made that in the complex and fluid environment of joint operations unity of effort is paramount, and coordination problems are ideally addressed prior to deployment and not during the operation.

It is fair to argue, however, that Army’s size (including its planned growth of 8.6%) and, its doctrinal recognition of deploying with OCS supported coalition partners such as the US may delay the organisational need for developing comprehensive, and fully integrated PAS policies for contractors in joint operations. Instead, Army could examine the possible niche roles contractors could perform in dispersed operations. With the ever-growing size of operational environments and the attendant decrease in military footprints deployed to these areas, logistics becomes a complex undertaking. For the time being, national strategic guidence directs that contractors be part of the Total Force and that they play important roles in allowing the provision of contract support for defence functions. For Army, this translates into operational contract support being comprehensive enough to align with the commander’s intent, and at the same time, display flexibility in relation to fluid battlespace requirements. This is not, by any means, a commercially dependent relationship.

Recommendations for further research

As joint operations are now a key characteristic of ADF doctrine, further research for joint, integrated OCS models will enable the ADF to examine in depth, and within the confines of its own warfighting doctrine requirements, what best practices are available for OCS employment. With this in mind, the following research avenues are proposed:

- Identify the organisational requirements for PAS and whether significant structural evolution/ and or change in the ADF would be required to house it as a new joint, integrated capability platform.

- As operational environments can never be fully predicted, what future options can be developed to provide force protection to contractors during joint operations without reducing the weight of the commander’s front-line combat force?

Conclusion

For the ADF, and Army in particular, understanding the deep structural relationship between the US DoD and its attendant OCS platform is an important conceptual requirement. This requirement was best expressed under the rubric of joint operations and what impact OCS has on coordinating the known complexity of joint all-arms operations. With all land operations

for Australia being inherently joint in nature, and the fluidity of operational requirements exerting added strain on supporting functions, a more detailed understanding of OCS is valuable to future guidance on how best to utilise contractor support. At a national security level, this requirement is reinforced through the high-order direction given by the 2016 White Paper on Defence. The planned deeper levels of interoperability and military engagement with the US DoD necessitate a thorough appreciation of how the US plans to sustain its forces during coalition operations via a large, commercially contracted work force. To illustrate this, the paper examined the comprehensive OCS concept, codified in JP 4-10, and distilled its essential characteristics. Of key importance to this process was identifying the challenges JP 4-10 creates in joint operations (despite its detailed organisational construct) and what input Army can use for its future OCS development.

Endnotes

- The research for this article was funded in part by the Australian Army Research Scheme

- Brigadier David Saul, 2007, ‘Hardened, Networked …and Commercially capable: Army and contractor support on operations’, Australian Army Journal, Vol 4, No 3, pp 105-114, accessed 12 Sep 2016 at

- Tim McCormack and Rain Liivoja, 2012, Australia: Regulating Private Military and Security Companies, Selected Works of Rain Liivoja, University of Melbourne, at

- These works include, Mark Thomson, 2005, War and Profit: Doing Business on the Battlefield, Australian Strategic Policy Institute Strategy Paper, March 2005, Brigadier David Saul, 2007 ‘Hardened , Networked… and Commercially capable: Army and contractor support on operations’. Australian Army Journal, Vol 4 No 3, pp 105-114, accessed 12 Sep 2016 at http://www.army.gov.au/~/media/Army/Our%20future/Publications/ AAJ/2000s/2007/AAJ_2007_3.pdf; Alex Gerrick, 2008, The Proliferation of Private Armies and their Impact on Regional Security and the Australian Defence Force, Centre for Defence and Strategic Studies; Tim McCormack and Rain Liivoja, 2012, Australia: Regulating Private Military and Security Companies, Selected Works of Rain Liivoja, University of Melbourne, available at http://works.bepress.com/rain_liivoja/20/ ; Susan Neuhaus and Glenn Keys, 2010, ‘Private Military Companies in the Operational Health Care Environment: pragmatism or peril?’ Australian Defence Force Journal, Issue No 182, pp 16-25

- A key contract is for the replacement of the Collins Class Submarines with 12 future submarines announced in the 2016 Defence White Paper at a cost of approximately $50 billion

- Operation PACIFIC ASSIST 2015 is emblematic of various second and third order tasks performed by the ADF

- Defence White Paper 2016, p 23

- This concept is discussed in depth in, ‘EU Concept for Contractor Support to EU-led Military Operations’, 7 April 2014, available at http://register.consilium.europa.eu/doc/srv?l=EN&f=ST%208628%202014%20I…

- This conceptual demarcation also underlines the commercial nature of OCS. The US Army has termed this as ‘commercial augmentation. See, ‘Operational Contract Support Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures’ ATTP 4-10, Jun 2011, Department of the Army, accessed 2 Aug 2016, at http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/policy/army/attp/attp4-1…

- In 2011, the Commission on Wartime Contracting estimated that between $31-$60 billion were lost, wasted or unaccounted for during recent combat operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. See, ‘Transforming Wartime Contracting – Controlling Cost, Reducing Risk’, Commission on Wartime Contracting, accessed Aug 4, 2016 at https:// cybercemetery.unt.edu/archive/cwc/20110929213820/http://www. wartimecontracting.gov/docs/CWC_Fi nalReport-lowres.pdf

- Civilian/military units have been extensively used by the US government in its operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. Provincial Reconstruction Teams (PRT) were the most commonly employed hybrid unit in Iraq and experienced widespread deployment by the Coalition Provisional Authority. PRTs were primarily lead by the Department of State but were comprised of a mix of civilian and military specialists. PRTs represented the US DoD’s prioritisation of stabilisation and reconstruction operations as core strategic missions in the Iraqi theatre

- ‘Operational Contract Support Concept of Operations’, US Department of Defense March 31, 2010, p 9, accessed Jul 29, 2016, at http://www. acq.osd.mil/log/ps/.ocs.fcib/OCS_Concept_of_Operations_2010.pdf

- ‘Operational Contract Support Concept of Operations’, US Department of Defense March 31, 2010, pp 2-3, accessed Jul 29, 2016, at http://www.acq.osd.mil/log/ps/.ocs.fcib/OCS_Concept_of_Operations_2010…

- The concept of Total Force in the US DoD lexicon is understood as a tripartite alliance between Military, Civilian and Contractor components. As early as 2006, the US QDR defined the Total Force as, ‘The Departments Total Force – its active and reserve military components, its civil servants, and its contractors – constitutes its warfighting capability and capacity…’ Quadrennial Defence Review Report, February 6, 2006, accessed 9 Jul 2016, at http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/policy/dod/qdr-2006-repo…

- ‘Operational Contract Support Concept of Operations’, US Department of Defense March 31, 2010, p 17, accessed Jul 29, 2016, at http://www.acq.osd.mil/log/ps/.ocs.fcib/OCS_Concept_of_Operations_2010…

- Available at http://www.dtic.mil/doctrine/concepts/joint_concepts/jic_opcontsupport…

- Major General Darrell K Williams and Lieutenant Colonel (Ret) William C Latham Jr, 2 May, 2016, ‘Sustainers should understand operational contract support’, accessed 14 Aug, 2016 at https://www.army.mil/

- ‘Joint Publication 4-10, Operational Contract Support, 16 July, p IX, 2014, accessed 10 Aug 2016, at http://www.dtic.mil/doctrine/new_pubs/jp4_10.pdf

- ‘Joint Publication 4-10, Operational Contract Support, 16 July, 2014, accessed 10 Aug 2016, at http://www.dtic.mil/doctrine/new_pubs/jp4_10.pdf

- Joint Publication 4-10, Operational Contract Support, 16 July 2014, p 17, accessed 10 Aug 2016, at http://www.dtic.mil/doctrine/new_pubs/jp4_10.pdf

- The full description of the JLLP is “to enhance joint capabilities by contributing to improvements in doctrine, organisation, training, material, leadership and education, personnel and facilities as well as policy”. See: Government Accountability Office, March 2015, Operational Contract Support: Actions Needed to Enhance the Collection, Integration and Sharing of Lessons Learned, accessed 20 Aug 2016., at

- Joint Publication 4-10, Operational Contract Support, 16 July 2014, p 22, accessed 10 Aug 2016, at http://www.dtic.mil/doctrine/new_pubs/ jp4_10.pdf

- Joint Publication 4-10, Operational Contract Support, 16 July 2014, p III-7, accessed 10 Aug 2016, at http://www.dtic.mil/doctrine/new_

- Joint Publication 4-10, Operational Contract Support, 16 July 2014, p III-10, accessed 10 Aug 2016, at http://www.dtic.mil/doctrine/new_

- AC-AFLOC, Adaptive Campaigning – Army’s Future Land Operating Concept, p 5, Chpt 1, Sept 2009, accessed 23 Sep, 2016 at http:// www.army.gov.au/~/media/Army/Our%20future/Publications/Key/

- Joint Publication 4-10, Operational Contract Support, 16 July 2014, p V-10, accessed 10 Aug 2016, at http://www.dtic.mil/doctrine/new_

- US Army Operational Contractor Support Tactics, Training and Procedures, ATTP 4-10, Jun 2011, accessed 14 Aug 2016, at http://

- Joint Publication 4-10, Operational Contract Support 16 July 2014, p III-11, accessed 10 Aug 2016, at http://www.dtic.mil/doctrine/new_

- Taken from Joint Publication 4-10, Operational Contract Support, 16 July 2014, p II-1, accessed 10 Aug 2016, at http://www.dtic.mil/

- Defence White Paper 2016, p 35

- Defence White Paper 2016, Chpt 1 para 1.27

- Australian Army: Our Future. Army modernisation update, April 2014, accessed 24 Oct 2016, at http://www.army.gov.au/~/media/Army/ Our%20future/Publications/Key/Modernisation%20update/Army%20m odernisation%20update%202014.pdf

- AC-AFLOC, Adaptive Campaigning – Army’s Future Land Operating Concept, p 5, Chpt 1, Sep 2009, accessed 23 Sep, 2016, at http:// www.army.gov.au/~/media/Army/Our%20future/Publications/Key/

- Land Warfare Doctrine 1: The Fundamentals of Land Power, p 8, Chpt 1, 2014, accessed 20 Sep, 2016, at http://www.army.gov.au/~/media/

- See Mark Thomson, 2005, War and Profit: Doing Business on the Battlefield, Australian Strategic Policy Institute Strategy Paper, March 2005