Abstract

This article examines the combined arms imperative driving Plan Beersheba. It begins by describing the major organisational changes occurring in the regular manoeuvre formations of Forces Command as background to discussion of the combined arms imperative behind these organisational changes. Evidence of this imperative is supported by historical analysis of combined arms warfare during the twentieth century and the Australian Army’s experience of employing tanks in Vietnam. The more recent experience of our allies in operations in the Middle East, our experience in mission-specific and foundation warfighting collective training exercises and lessons from the Restructuring the Army trials of 1998–99 will add a more modern edge to this analysis.

The organisation which assures unity of combatants should be better throughout and more rational … soldiers no matter how well drilled, who are assembled haphazardly into companies and battalions will never have, never have had, that entire unity which is borne of mutual acquaintanceship.

- Colonel Ardant du Picq

Introduction

Had Colonel Ardant du Picq been given the opportunity to observe the Australian Army’s traditional methods of temporarily task-organising into battlegroups for combined arms training activities he may well have criticised it as ‘haphazard’. For Exercise Talisman Sabre (Hamel) in late July 2013, an armoured cavalry regiment (ACR), a task-organised battlegroup formed around the 1st Armoured Regiment with attachments from other mechanised units of the Darwin-based 1st Brigade, was attached to the 3rd Brigade. Exercise Hamel has been conducted every year since 2010 and these exercises, along with the respective brigades’ annual Combined Arms Training Activity (CATA) which pre-dates Exercise Hamel, have provided the manoeuvre brigades of the Australian Army the opportunity to collectively train in combined arms. Prior to each Hamel and CATA, the armoured and mechanised units of the 1st Brigade are temporarily task-organised for these training activities, often detached from the 1st Brigade to the 3rd Brigade, and then embark on a lengthy and expensive transit to and from training areas in central Queensland. Here they perform some hasty re-familiarisation between tank, infantry and artillery and their supporting arms and services, conduct the training activity and, on its conclusion, make the lengthy trek to return to their garrison locations.

Having observed this training model, while acknowledging that its soldiers were individually well trained, du Picq would probably conclude that the Australian Army’s combined arms battlegroups and brigades (when formed) have never had and could never have that entire unity which he regarded as born of ‘mutual acquaintanceship’. This is because, until Plan Beersheba, the Australian Army’s organisation and the temporary nature of its approach to combining arms has precluded ‘mutual acquaintanceship’ and thus constrained its combined arms capability. Now, for the first time, instead of reorganising into its parent unit organisations, the 1st ACR will retain as far as possible its Exercise Hamel ACR organisation and prepare to transition to its new Plan Beersheba establishment in January 2014.1 This new structure will see tanks, infantry and artillery permanently organised in each Multirole Combat Brigade (MCB).

This article will examine the combined arms imperative underpinning and driving the most significant reorganisation of the Army in decades. It will begin by describing the major organisational changes occurring in the regular manoeuvre formations of Forces Command before outlining the combined arms imperative driving these organisational changes. The discussion will focus on the argument that the organisational changes envisaged under Plan Beersheba reflect not only the professional judgements of Army’s senior leadership and thinkers, but also draw on lessons from combined arms warfare during the twentieth century and the Australian Army’s experience of employing tanks in Vietnam. More recent experience will also be examined, specifically that of our allies in operations in the Middle East, our experience in mission-specific and foundation warfighting collective training exercises and lessons from the Restructuring the Army trial (RTA) conducted in 1998–99.

Plan Beersheba

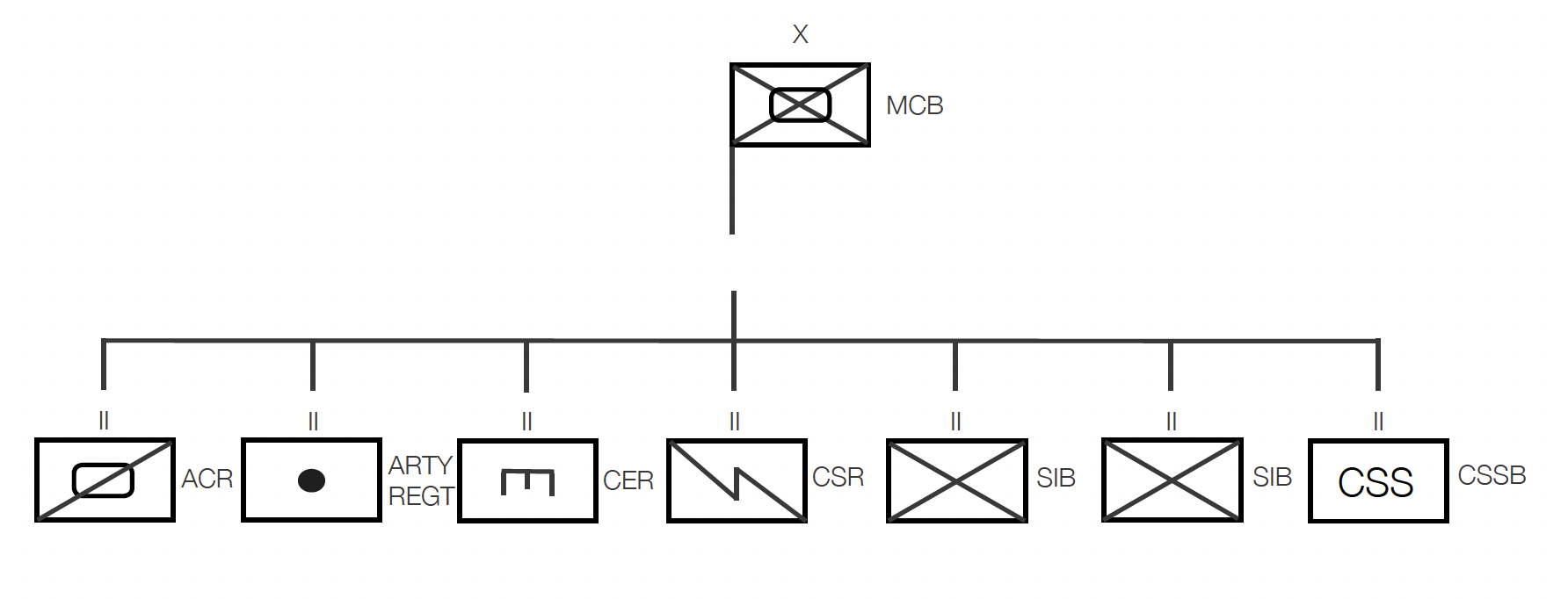

The 2013 Defence White Paper reaffirmed the government’s commitment to Army’s reorganisation under Plan Beersheba. Plan Beersheba will reorganise the Australian Army from the three specialised brigades into three ‘like’ MCBs based in Darwin, Townsville and Brisbane that will have fundamentally common structures containing all elements of the combined arms team.2 Each brigade will comprise two standard infantry battalions (SIBs) together with an ACR that includes a tank squadron, an artillery regiment, combat signals regiment (CSR), combat engineer regiment (CER), and combat service support battalion (CSSB).3 The structure of each like brigade is illustrated in Figure 1:

Figure 1: Organisation of the MCB

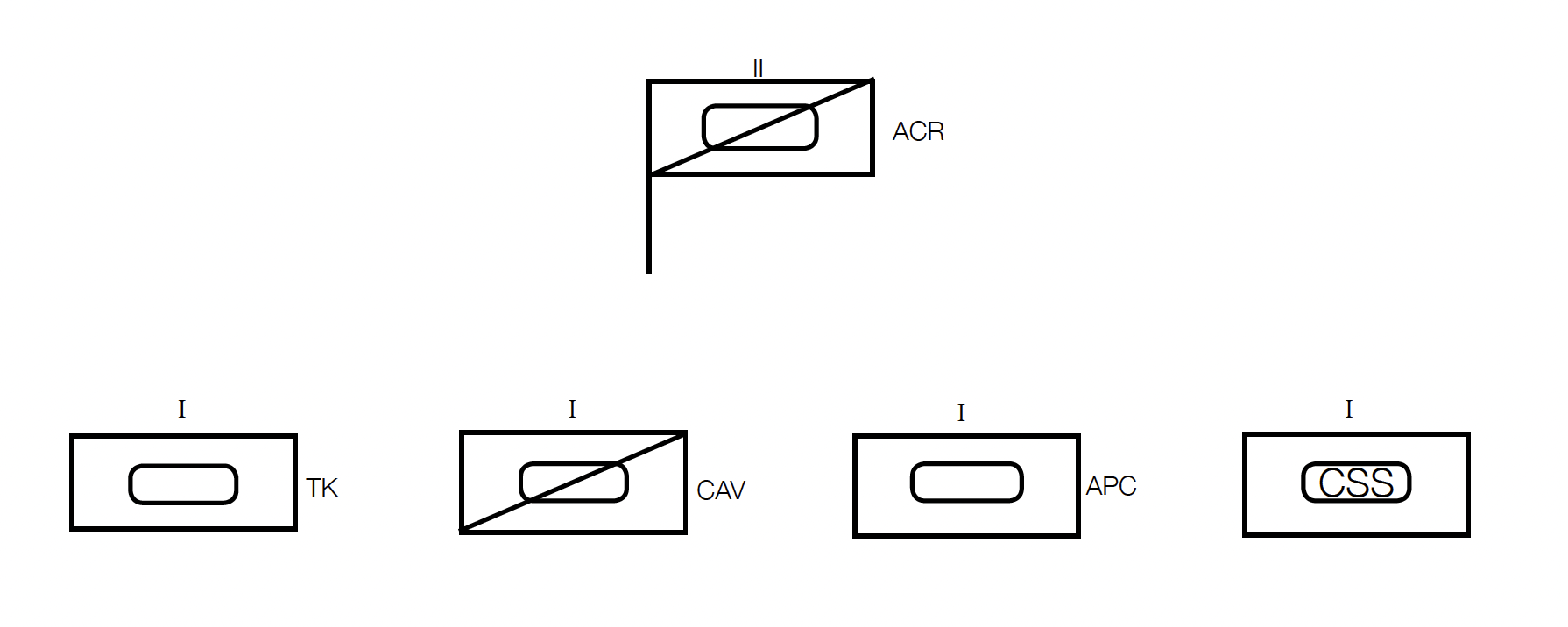

The most significant change will involve reorganising the tanks and APCs currently centralised in the armoured, cavalry and mechanised units of the Darwin and Adelaide-based 1st Brigade into ACRs based in each brigade’s location.

The structure of each ACR is illustrated in Figure 2:

Figure 2: Organisation of the ACR

In launching Plan Beersheba in December 2011, the Minister for Defence pointed to the need to integrate skills, a translation of ‘combined arms’ more easily understood by a public unfamiliar with the original meaning:

What we’ve learned from that experience is that Army is better placed if its skills are integrated. So we’re moving to three Brigades which will comprise and contain all of Army’s key skills – armour, infantry, communications, logistics and the like. This will enable flexibility – speedy response – but also make Army more efficient, and more effective.4

At the same conference the Chief of Army (CA), Lieutenant General Morrison, elaborated on the Minister’s explanation:

We need to have forces that are going to operate in barracks together, so that they can train together, as much as we can and clearly we will remain in Darwin and we’ll remain in Townsville, we’ll remain in Brisbane, we’ll remain in the various locations that Army occupies now in Australia. But we need to group assets together in a way that enables them to train as they would fight or operate at short notice. Without going into the specifics, what we will try and do is make our Brigades more like each other.5

These statements reveal the combined arms rationale behind Plan Beersheba.

So what does the term ‘combined arms’ actually mean? While a definition of combined arms has been lost from Australian doctrine,6 the pre-eminent historian of combined arms, Jonathan House, provides a concise explanation:

… the combined arms concept is the basic idea that different combat arms and weapons systems must be used in concert to maximise the survival and combat effectiveness of the others. The strengths of one system must be used to compensate for the weaknesses of others.7

Yet, in most explanations of the logic behind the Plan Beersheba reorganisation, the combined arms imperative driving the changes is in danger of losing its prominence. Most official statements and commentary refer to the benefits of generating forces for sustained operations that the reorganisation will bring. The Australian Army’s website notes that the Army’s manoeuvre brigades will ‘contain all elements of the combined arms team’ and refers to the need to ‘provide the widest range of sustained and effective land forces possible to meet future strategic circumstances’ and to ‘generate optimal capability to conform to strategic guidance and meet the challenge of contemporary warfare. It incorporates lessons learned over a decade of continuous operations, and maximises capability through the application of Army’s Force Generation Cycle.’8 In a 2012 speech the CA explained that:

… for too long we maintained single capabilities within brigades with deleterious effects on our force generation and career planning cycles. This was inefficient and probably harmed retention as well … The development of the standard multi-role brigade will enable Army to reach the objective set in the 2000 White Paper for us to be capable of providing a brigade for sustained operations within our primary operating environment. It also allows us to develop forces of a combat weight commensurate with the level of threat in the modern battlespace. The force generation implications of this are profound and will ensure that we meet our obligation to the Government, and the remainder of the ADF, to be able to undertake sustained joint operations both in the littoral approaches to Australia and throughout the immediate neighbourhood.9

However media reporting which followed the official announcement of Plan Beersheba in December 2011 failed to explicitly report the combined arms imperative that drove the changes. The Sydney Morning Herald, for example, reported that ‘the Australian Army will be radically re shaped to prepare it better for long campaigns such as the decade-long war in Afghanistan’.10

The combined arms imperative so critical to understanding the purpose and direction of Plan Beersheba and yet so neglected in media commentary forms the subject of the next section of this article.

The Combined Arms Imperative

For many years professional discourse within the Australian Army has identified the need for a combined arms capability. Few military professionals with an understanding of the ingredients of success in modern warfare would dispute the logic of a combined arms capability as the centrepiece of the Australian Army’s foundation warfighting tasks, although bizarrely, this view is not prominent in Army’s current doctrine.11 In his historical analysis of developments in combined arms warfare over three centuries, Michael Evans concludes that:

from Brietenfeld in 1631 to Baghdad in 2003, the ability to combine fire, protection and movement by different arms has been the key to success in close combat and represents an important measure of an army’s professional effectiveness. In close combat, no single arm or weapons system can succeed alone: infantry must be teamed with tanks and both must be linked to artillery.12

A case study of Australian combined arms assault operations in Vietnam between 1966 and 1971 demonstrates that a combination of infantry and armour remains vital to tactical success.13 Having examined more recent historical examples of combined arms cooperation in the assault, including Iraq, Alan Ryan concluded that ‘for the foreseeable future, the Australian Army will be required to maintain and continue to develop a balanced and lethal combined arms capability if it is to be able to fulfil its mission of fighting and winning the land battle.’14 Lieutenant Colonel David Kilcullen’s review of the discussion during the 2003 Infantry Corps Conference and of contemporary Israeli and British experiences in combat in the Middle East led him to the conclusion that ‘Australian Army force elements must operate as combined arms teams’. Kilcullen recommended that the Army ‘train and rehearse as we intend to fight in small, semi-autonomous combined arms teams’, adding that ‘the principles of battle grouping and task organisation to create combined arms teams need to be applied at a much lower tactical level in the future … possibly at intra-platoon or even intra-section level.’15

Australian officers with combined arms experience have also identified the organisational impediments to a true combined arms capability inherent in the Australian Army. One practitioner argues compellingly that the ‘organisation of our Brigades16 has resulted in our tanks and mechanised infantry having a habitual relationship, often at the expense of the remainder of our army, which has limited opportunity to train with, or experience the practical employment of tanks’.17 Kilcullen’s deduction that the principles of battle grouping and task organisation to create combined arms teams need to be applied at a much lower tactical level in the future led him to the view that ‘such an organisational shift may demand the creation of more modular structures that can be “sliced and diced” in different ways in order to enable rapid and flexible regrouping of forces for any given mission’.18

A balance needs to be struck however:

As the Israelis found in Jenin, the need for unit cohesion is the Achilles heel of the small fire team. When troops have not trained together, or are unused to rapid reorganisation, battle grouping at too low tactical level may simply damage unit cohesion and general morale. For these reasons there needs to be a focus on habitual training relationships.

Kilcullen concluded that the Australian Army needs to ‘focus intellectual and professional military effort on mastering combined arms operations in urbanised and complex terrain’.19 Plan Beersheba incorporates such objectives but through reorganisation in order to facilitate mastery of combined arms tactics to a degree that our current organisation has inhibited.

Lessons from combined arms warfare in the twentieth century

The history of combined arms in the twentieth century is replete with evidence that points to the importance of effectively organising combined arms. Jonathan House concluded that ‘to be effective the different arms and services must train together at all times, changing task organisation frequently.’ The pre-Plan Beersheba Army suffered from another of House’s observations from history: ‘confusion and delay may occur until the additions adjust to their new command relationships and the gaining headquarters learns the capabilities, limitations and personalities of these attachments.’ House argues that task organisation is more effective when it commences with a large combined arms formation, such as a brigade, and elements from it are selected to form a specific task force, rather than starting with a smaller unit and attaching elements to it. ‘This ensures that all elements of the task force are accustomed to working together and have a common sense of identity that can overcome many misunderstandings.’20 Plan Beersheba’s organisational changes implicitly acknowledge this lesson, its reorganisation allowing the ‘ready’ brigade commander to select tank, infantry, engineer and artillery elements from his or her brigade and task-organise them. At this point, the experience of shared combined arms training during the ‘readying’ phase will have provided the opportunity for these task force elements to have trained together and developed the common sense of identity so essential to effective combined arms.21 This will ensure that periods of confusion and delay caused by the attachment of armoured and mechanised elements from the mechanised 1st Brigade to the 3rd or 7th Brigades will be minimised in the Plan Beersheba Army.

An analysis of the Australian experience of the raising, training and disbanding of the 1st Armoured Division during the Second World War also supports the need for effective organisation of combined arms. The Australian 1st Armoured Division was formed for service in the Middle East and the defence of Australia during the Second World War. Uniquely in the Australian experience of armour, the division envisaged using tanks not in an infantry support role, but in operations independent of infantry. It was eventually disbanded without seeing combat, although several of its regiments fought in the South West Pacific Area. An important lesson from the 1st Armoured Division experience is that ‘when units are equipped differently and trained separately, they cannot operate effectively together, even in controlled exercise situations’. As such, ‘frequent intimate collective training between the Land 400 LVCS [Land Vehicle Combat System] and infantry battalions or embedding of these vehicles will be essential to the effective use of the system. This will result in higher required manning and maintenance liability due to the diffused force structure, but is essential to force effectiveness on operations.’22

Lessons from Vietnam

The experience of the 1 RAR Battle Group’s preparation for and operational service in Vietnam in 1965 warns against relying solely on pre-deployment training and ad hoc task-organised collective training for combined arms. The 1 RAR Battle Group that deployed to Vietnam in 1965 as part of the United States (US) 173rd Airborne Brigade had to be completely reorganised from its pentropic organisation.23 Combined arms training was not prominent in its pre-deployment preparation and training. As a result, shortly after its arrival in theatre, the 1 RAR Battle Group faced a rapid learning curve on large-scale command, control and communications, artillery and close air support, armoured, armoured personnel carriers (APC) and infantry operations, rapid ‘on the march’ orders and helicopter resupply.24

In 1973, at the end of almost eight years of unit and task force level experience in Vietnam, the Australian Army published Training Information Bulletin (TIB) Number 21 – The RAAC Regiment amending The Division in Battle Pamphlet #4 – Armour. The Royal Australian Armoured Corps (RAAC) was reorganised in doctrine from separate armoured, cavalry, APC and anti-tank regiments into RAAC regiments. Within a divisional structure, the role of the RAAC was to provide support for the infantry, to operate in the mobile role whether supported by, or in support of, other arms, and to provide long-range anti-tank defence. The publication acknowledged that the tank’s principal task in the South-East Asian environment was to provide intimate close support for infantry. The Army’s experience demonstrated that five types of sub-unit were required within a RAAC regiment: cavalry, tank, armoured personnel carrier (APC), anti-tank (for limited war only) and forward delivery (or combat service support in contemporary terminology).

A comparison between this structure and the ACR depicted in Figure 2 shows the similarities, with only an anti-tank sub-unit absent from the Plan Beersheba ACR structure. TIB 21 stated that, during counter-insurgency operations when the armoured squadrons are collocated with the task force, it would be normal to task- organise the three squadrons as an RAAC Regiment. It identified the advantages of this organisation as: the availability of one senior experienced armour advisor to the task force commander instead of three squadron commanders; better allocation of armoured resources; centralised and simplified administration and management of logistic resources; and the flexibility to deploy independent squadrons as necessary. This was essentially the organisation that Army acknowledged as optimal for operations involving armour in South-East Asia. Due to the comparative costs of having tanks in separate geographic localities, the support requirements of the Centurion and a focus away from counterinsurgency to conventional operations, the structure was only partially adopted. While the 2nd Cavalry Regiment from the Holsworthy-based 1st Task Force and the 4th Cavalry Regiment of the 6th Task Force in Enoggera were reorganised with A Squadron Reconnaissance and B Squadron APC, the Centurion tanks remained centralised with the 1st Armoured Regiment in Puckapunyal and C Squadron’s tanks were never attached to the cavalry regiments. The RAAC regiment concept was overtaken by TIB 28, The Infantry Division, in 1975, and the Army returned to focusing on conventional operations and grouping separate tanks, APC and reconnaissance regiments.25

Lessons from allies

A combined arms imperative was the impetus for the US Army’s reorganisation into permanent combined arms battalions and brigades. In the late 1980s the US Army experimented by organising three combined arms manoeuvre battalions (CAMB). This organisational structure had as its objective ‘organising battalions to train as they will fight’. The intended benefits of this reorganisation were to improve leaders’ proficiency in integrating tanks and mechanised infantry, facilitate task organisation and sustainment and capitalise on the effects of constant association. The reorganisation was also expected to reap long-term professional development benefits by exposing leaders to combined arms.26 The logic driving the US Army’s CAMB reorganisation saw greater benefit from permanently organising as combined arms than continuing to live as ‘pure’ mechanised infantry and tank units that only cross-attach and task-organise occasionally.27 One of its goals was to strengthen armoured-infantry teamwork by enabling units to live and work together. The US experience also addressed the counter-argument to permanent reorganisation. US proponents of the CAMB highlighted the inefficiencies created by such provisional task-organisation including the creation of additional and unfamiliar administrative, technical and governance requirements. Institutionalising combined arms through the CAMB reorganisation removed this problem.28 Following this experiment the CAMB model was implemented during the 2004 transformation of the US Army.29 Combined arms battalions and brigade combat teams are now the main organisational structures of the US Army and point to the advantages of permanently organising combined arms at brigade level. While the Plan Beersheba reorganisation is different to that of the US Army at battalion and brigade level, it is driven by the same valid combined arms imperative.

Lessons from collective training activities

Lessons from mission-specific pre-deployment training also support the argument for permanently task-organising for combined arms. A junior non-commissioned officer who served with Security Detachment (SECDET) III in Iraq in 2004–05 noted in an interview that an increased level of interoperability between all force elements must be achieved prior to deployment: ‘Having opportunities to work with the military police, cavalry personnel and their vehicles, and other elements are essential to minimise interoperability issues.’ He suggested that the Army ‘shouldn’t wait until [units are] deployed to discover that there aren’t common TTP or SOP.’30 An ASLAV crewman from the Afghanistan-bound Reconstruction Task Force (RTF) 2 in 2007 recalled that the first time he experienced combined arms training was during the Mission Rehearsal Exercise (MRE). While he considered that his unit was proficient by the end of training, he commented that, ideally, the unit should have had more regular exposure to this training beforehand.31 While SECDET and RTF were unique, highly task-organised teams created for very narrowly defined missions, and the Army’s future combined arms must be kept more broad and generic than these examples, they nevertheless demonstrate the existing combined arms deficiencies within the Australian Army.

In post-deployment debriefings a small group of artillery officers who had re-roled as infantry and deployed on Operation ANODE in 2007 also argued the importance of conducting combined arms training as a regular activity. They believed that it was important for all force elements to develop teamwork and awareness of one another’s capabilities in order to ensure that they worked together effectively while on operations. All stated that they had undertaken very little combined arms training outside mission-specific training (MST) and Combat Training Centre MREs. They suggested that battle grouping should become a regular feature of Army’s business — they clearly saw some value in assembling regular battlegroups in barracks as well as on operations. The officers interviewed had been in their unit for at least two years and could not remember ever having undertaken any form of combined arms training.32 These contemporary observations on the need for ‘mutual acquaintanceship’ closely mirror those of Colonel Ardant du Picq whose comments were reflective of nineteenth-century reality.

One clear advantage of the Plan Beersheba reorganisation is the increased flexibility enjoyed by the brigade commander and an obvious boost in resourcing. Previously, when the 3rd or 7th Brigade wanted to conduct combined arms training with the tanks or APCs of the 1st Brigade, it would require HQ FORCOMD involvement to facilitate the arrangement. Under Plan Beersheba, when the ‘readying’ or ‘ready’ MCB wants to conduct combined arms training, the tank (under one model being considered), APC or cavalry sub-unit is readily available in the brigade’s collocated and integral ACR. Should this model eventually be adopted there would be a significant reduction in the enormous costs associated with the transportation of tanks to eastern Queensland.33

Lessons from previous trials

Lessons from the Restructuring the Army for the 21st Century (RTA/A21) trial include a number that are relevant to Plan Beersheba. In a brief to the Minister in May 2000, the trials director, then Colonel Justin Kelly, explained one of the main findings of the trial:

Army 21 sought to achieve combined arms effects by creating units which contained small numbers of the principal arms – tanks, artillery, infantry and engineers. What we found was that these permanent groupings offered no advantages over temporary groupings created for a specific task and were in fact less flexible. The embedded units were also difficult to train and administer and undermined the culture of excellence that has traditionally given us the edge at the tactical level. On the whole, the A21 approach to combined arms proved to be a more expensive way to achieve a lesser outcome. The trial reinforced that the brigade level was the most efficient and effective means of generating combined arms effects because of its command and logistics capabilities. We decided that embedding should occur at that level rather than at the unit or sub-unit level [author’s emphasis].’34

The RTA trial confirmed what many RAAC officers had deduced from professional experience and had warned against as the trial approached: that embedding a troop of tanks at sub unit level in a reconnaissance squadron was too low a level of combined arms integration.35 Disadvantages included the loss of flexibility and ability to mass combat power, the inability to concentrate fire, the constraints imposed by dissimilar tracked and wheeled vehicle capabilities, and the difficulty in supporting and sustaining the embedded tanks in geographically dispersed locations. One experienced tank commander concluded that ‘a Tank Squadron offers greater flexibility and impact than the single discrete troop embedded within the reconnaissance squadron.’36 Another argued that ‘the issue is not whether we should embed or group but rather at what level we should embed.’37 The trial ‘confirmed that artillery, tanks and infantry continue to be at the core of the combined arms battle … without artillery, company attacks against adversary platoons invariably failed’ and ‘the presence of a single troop of three tanks in an infantry company attack typically reduced casualties by two-thirds.’38

Plan Beersheba and the RTA trial both aimed to achieve an improved combined arms effect. The RTA trial method was an organisational restructure of units to embed armour and artillery at unit level. The Plan Beersheba method is, among other things, an organisational restructure to ensure that all arms, including tanks, are permanently represented within each brigade. This method is consistent with the conclusion from the RTA trial that embedding combined arms effects should occur at brigade level. RAAC officers should be encouraged that, on this occasion, Army’s method reflects the lessons learned from previous trials that embedded tanks and from the advice offered by professional practitioners. Interestingly, the Army had not acted on that key finding until Plan Beersheba, possibly reflecting the demands of sustained operations from late 1999 to the present.

Acknowledging the challenges and risks

As the RTA trial director concluded in 2000, ‘achieving the right balance between breadth, depth and resources is the core challenge of Army development’.39 This observation remains true for Plan Beersheba. There are many risks and obstacles associated with the disaggregation of armoured units into mixed RAAC groupings and these risks and obstacles apparently prevented the realisation of the reorganised 1973 RAAC Regiments that the Army envisaged following its Vietnam experience. One significant concern remains with the model that sees the disaggregation of tanks into three geographic locations. This concern is that, having a tank squadron in each geographic location risks never actually seeing a full squadron fielded due to maintenance and serviceability constraints. It is a regimental effort for the 1st Armoured Regiment to put a tank squadron in the field. Similarly, there is a risk of degradation of core skills such as gunnery as a consequence of adopting the model that sees the disaggregation of tanks. In order to ensure that Plan Beersheba does not suffer the same fate as the post-Vietnam RAAC regiment, these risks and obstacles need to be adequately addressed through simulation systems, heavy tank transporters, recovery variants and through life support contract arrangements. Maintaining main battle tanks in one location and ASLAVs in two currently presents a significant challenge and, under one Plan Beersheba model that will be considered, Army will need to support and sustain these platforms across three or four locations.40 Army’s senior leadership is well aware of these risks and obstacles and Army’s planners are working hard to address them as implementation plans and models are drafted. Nothing has yet been identified however, that trumps the combined arms imperative that is driving the need for change.

Conclusion

In 1993, having analysed the historical imperative for the combined arms team and examined the structure of the US Armoured Cavalry Regiment, a young Australian RAAC officer wrote that the Australian Army was good at ‘espousing the benefits of all arms training at RMC and JSC and on formation level exercises, but not in the day-to-day conduct of training.’41 Perhaps constrained by his rank and experience he did not then advocate the formation of armoured cavalry regiments in the Australian Army but saw the 1st Brigade as providing the basis for a number of all-arms teams with the capability and flexibility of an armoured cavalry unit. Plan Beersheba takes the well-founded and prescient observations of this young officer beyond the 1st Brigade in which he served and into all the regular manoeuvre brigades of the Australian Army. While no doubt there are efficiencies and advantages in sustaining operations, the combined arms imperative is the pre-eminent rationale for Plan Beersheba. This pre eminence reflects the professional judgement of Army’s senior leadership and thinkers, and draws on lessons identified in an historical analysis of combined arms warfare during the twentieth century. Such lessons include those from the Australian Army’s experience of employing tanks in Vietnam, the experience of our allies in recent operations in the Middle East, our experience in collective training exercises and lessons from RTA/A21 conducted in 1998–99. While conceptualising Plan Beersheba has brought its own challenges, these will be overshadowed by the challenges inherent in implementing the reorganisation over the next ten years. After that, perhaps the next challenge and the focus of contemporary experimentation may lie in generating ‘mutual acquaintanceship’ between the MCBs and the supporting arms and services that currently reside in the 6th, 16th and 17th Brigades.

Endnotes

1 This may not be the final unit name of the Darwin (or Adelaide)-based ACR, as that decision will be made by CA on the advice of the RAAC Head of Corps.

2 Defence White Paper 2013, p. 86 and at:http://www.army.gov.au/Our-future/Plan-BEERSHEBA

3 J. Kerr, ‘Beersheba Plans for when the Troops come home’, The Weekend Australian, 27 October 2012.

4 Minister for Defence, Transcript of Press Conference of 12 December 2011 announcing Plan Beersheba at: http://www.minister.defence.gov.au/2011/12/13/minister-for-defence-press- conference/

5 Ibid.

6 In LWD 3-0 Operations and LWD 3-0-3 Land Tactics combined arms teams are defined as ‘a case-by-case mix of combat, combat support, CSS and command support FEs, selected on the basis of a specific combination of task, terrain and threat.’ The concept of combined arms itself is not explained.

7 J. House, Combined Arms warfare in the Twentieth Century, University Press of Kansas, 2001, p. 4.

8 Ibid., p. 282.

9 Chief of Army, Lieutenant General David Morrison, AO, address to the Royal Australian Navy Maritime Conference, Sydney, 31 January 2012.

10 D. Oakes, ‘Army Shapes up for the Long Haul’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 13 December 2011.

11 For one perspective see Lieutenant Colonel M. Krause, ‘Lest we Forget – Combined Arms Assault in Complex Terrain’, Australian Army Journal, Vol. I, No. 1, pp. 41–46.

12 M. Evans, ‘General Monash’s Orchestra – Reaffirming Combined Arms Warfare’ in Michael Evans and Alan Ryan (eds), From Brietenfeld to Baghdad – Perspectives on Combined Arms Warfare, Land Warfare Studies Centre, Working Paper No. 122, July 2003.

13 R. Hall and A. Ross, ‘Lessons from Vietnam – Combined Arms Assault against Prepared Defences’, in Evans and Ryan (eds), From Brietenfeld to Baghdad – Perspectives on Combined Arms Warfare.

14 A. Ryan, ‘Combined Arms Cooperation in the Assault – Historical and Contemporary Perspectives’ in Evans and Ryan (eds), From Brietenfeld to Baghdad – Perspectives on Combined Arms Warfare, p. 58.

15 Lieutenant Colonel David Kilcullen, ‘The Essential debate – Combined Arms and the Close Battle in Complex Terrain’, Australian Army Journal, Vol. I, No. 2, pp. 77–78.

16 Since 1980 the Australian Army had been organised on distinctive specialised brigades cantered around mobile/mechanised capabilities, light, air-portable capabilities, and standard infantry/motorised capabilities. Lieutenant General Dunstan, then Chief of the General Staff , proposed the following specialisations for the task forces of the 1st Division: 1st Task Force was to focus on mobile operations and prepare for tasks in conjunction with the 1st Armoured Regiment; 3rd Task Force was to be reorganised onto light scales, and it was to concentrate its training on air-portable and air-mobile operations as well as warfare in tropical areas; 6th Task Force was to remain a standard infantry task force, focusing its training on conventional operations in open country. Dunstan’s logic was that, in an organisation as small as the ARA, it was a liability to have three task forces with identical organisations and roles, as this limited the Army’s ability to develop the full range of skills it might require for expansion. See Dr Albert Palazzo, The Australian Army – A History of its Organisation 1901 2001, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 2001, p. 328.

17 Captain M. Shea, ‘Infantry/tank cooperation in complex terrain’, Australian Infantry Magazine: Magazine of the Royal Australian Infantry Corps, October 2002, pp. 48–51.

18 Kilcullen, ‘The Essential debate’, p. 79.

19 Ibid. p. 80.

20 House, Combined Arms warfare in the Twentieth Century, p. 282.

21 Forces Command generates foundation warfighting capabilities using a force generation cycle in which a given brigade will be in the ‘ready’ phase from which forces are drawn for current operations and contingencies, another brigade will be in the ‘readying’ phase or conducting collective training in foundation warfighting to prepare for current or contingency operations, and a further brigade will be in the ‘reset’ phase in which the focus will be on individual training and modernisation.

22 Lieutenant Zach Lambert, ‘The Birth, Life and Death of the 1st Australian Armoured Division’,

Australian Army Journal, Vol. IX, No. 95, p. 100.

23 The pentropic battalion organisation had five rifle companies and an Administrative and Support Company. Five infantry battalions with supporting arms and services made up the Pentropic Divisions. See Palazzo, The Australian Army, pp. 249–50.

24 B. Breen, First to Fight, Allen & Unwin, North Sydney, 1998, p. 34 cited in Lieutenant Jason Novella, ‘The Effectiveness of the 1st Battalion’s Combined Arms operations During its First Tour of Vietnam’, Australian Infantry Magazine, October 2005, pp. 28–30.

25 E-mail correspondence between Mr Bill Houston, Army History Unit, and Brigadier Chris Field, Chief of Staff, HQ FORCOMD of 11 July 13 made available to the author.

26 Lieutenant Colonel R.G. Bernier, ‘The Combined Arms Manoeuvre Battalion – Armour and Infantry Build a New Relationship in Fort Hood Experiment’, Armor, January–February 1998, p. 14.

27 Ibid., p. 15.

28 Ibid., p. 16.

29 E-mail from HQ FORCOMD Director General Training Brigadier Prictor of 7 August 2013. Brigadier Prictor has had exchange and professional military education postings with the US Army.

30 OBS000001591, ALO Knowledge Warehouse. All footnotes with a number prefixed by ‘OBS’ are observations drawn from the Australian Army Centre for Army Lessons, Army learning Organisation (ALO) Knowledge Warehouse.

31 OBS00000621.

32 OBS000005854.

33 This was also an identified benefit of the US Army’s CAMB organisational experiment. See Bernier, ‘The Combined Arms Manoeuvre Battalion – Armour and Infantry Build a New Relationship in Fort Hood Experiment’, Armor, p. 18.

34 Colonel Justin Kelly, Presentation delivered to the Minister of Defence on RTA Trials Report, 24 May 2000 accessed at ALO Knowledge Warehouse on 25 July 2013.

35 See 1 Armoured Regiment professional journal The Paratus Papers from 1997 and 1998 for the arguments of tank officers for and against embedding tanks.

36 Major D.M. Cantwell, ‘Tanks in the Reconnaissance Battalion – Grouping, Tasks and Tactics’,

Paratus Papers, 1997.

37 Major N. Pollock, ‘Tanks – Embedded or Grouped?’, Paratus Papers, 1997.

38 Kelly, presentation on RTA Trials Report, 24 May 2000.

39 Ibid.

40 I am grateful for the comments of Lieutenant Colonel S. Winter, CO 1 Armoured Regiment and CO of the ACR during Ex Hamel 2013 on the need to highlight these identified risks and obstacles. I am grateful also to Major C. Morrison, HQ FORCOMD, for his comments relating to the need for a regiment-sized armoured organisation to deploy a squadron.

41 Captain Jason Thomas, ‘The Armoured Cavalry Regiment as a Model for the All Arms Team’,

Combined Arms Journal, Issue 2/93, p. 31.