Abstract

The current landscape of military operational thinking is dominated by the complex warf- ighting paradigm that embodies a shift to war among the people. In such wars, the precise application of force to produce effects — targeting — is critical to achieving military objec- tives while supporting civil aims and avoiding undesired outcomes. Contemporary warfare challenges the practice of targeting and the philosophy of its purpose, promoting a shift from targeting for effect to targeting to learn. This examination of the find, fix, finish, exploit, assess (F3EA) construct provides insights into the evolution of the targeting problem and the current solution, revealing strengths, limitations, and opportunities for change.

Introduction

The current landscape of military operational thinking is dominated by counterinsurgency, as clearly demonstrated in Iraq and Afghanistan from 2001 through to the present day. This paradigm represents a shift from the late 20th century focus on industrial warfare (the legacy of state-based wars, particularly the Cold War and Gulf War I) to a less complete, more transient form of conflict that takes place among the people.1 Contemporary warfare poses several clear challenges to established doctrine and processes given the enormous changes in technology, in the nature and aims of the adversary, and in the operational environment.2 In particular, the practice of targeting — the application of force to produce an effect on selected battlespace elements — is adapting rapidly and dramatically to the new face of warfare.

This article will describe both the current and emerging approaches to targeting and highlight their advantages and disadvantages in terms of the current and future requirements of the ADF. The article’s purpose is to demonstrate a shift in the fundamental aims of targeting in contemporary conflict from targeting to effect to targeting to learn.

Targeting

The purpose of targeting in the contemporary context and as it is applied to current conflicts is defined by ADF doctrine as ‘to integrate and synchronise joint fires [and] the employment of lethal and non-lethal weapons into joint operations to achieve the joint commander’s mission, objective and desired effects.’3

Targeting thus relates to any action or process in which force (lethal, non-lethal or a combination of capabilities) is intentionally applied to change the state of a target. A target is defined as ‘an object of a particular action, for example a geographic area, a complex, an installation, a force, equipment, an individual, a group or a system planned for capture, exploitation, neutralisation or destruction by military forces.’4

Targets are divided into types: scheduled or on call, unplanned or unanticipated. The type of target is related not only to its inherent proper- ties, but also to the capabilities of the attacking force and the nature of the targeting environ- ment. Planned targets (scheduled or on call) normally emerge from a target system analysis (TSA) developed during military planning.

The TSA defines those adversary system elements that must be affected in order to achieve the commander’s objectives. The application of the targeting process to planned targets — the shaping of the battlespace — is a deliberate approach. Targets labelled ‘unplanned’ or ‘unanticipated’ can also be considered targets of opportunity; the generation of effects against these targets involves a dynamic targeting approach.5

Contemporary warfare is of a complex and often asymmetric nature which poses challenges to understanding adversary systems. Where limited understanding of the adversary and environment exists, dynamic targeting both shapes and manages the battlespace. The application of planned targeting is limited and almost exclusively non-kinetic (this is increasingly the case as conflicts extend to counterinsurgencies). In this case, targeting is considered not as a process, but as a conceptual framework for directed operations within the context of a larger campaign.

Targeting concepts

Discussion of targeting concepts can be broadly separated into examination of the general targeting approach and analysis of the approaches adapted to dynamic targeting. The general targeting approach, which gives rise to the targeting process that remains largely unchanged and occurs over extended time-frames, normally in conjunction with a deliberate planning process, is essentially the same across the US allies, and adheres generally to US doctrine.

The targeting process is a linear set of procedural steps that must occur regardless of the target system, situation, type of weaponry or type of conflict. The targeting construct suppresses intricate detail and drives focus towards important concepts. Essentially, it is an attempt to frame the targeting problem in a way that will assist decision-making.6 This has several immediate advantages:

- A targeting model allows a commander to understand the targeting process in his current context. It is not the steps at the procedural level that change, but the way they are executed.

- A model enables a commander to organise and manage his force according to the specific meta-task requirements relating to the current targeting problem represented by the targeting construct.

- Targeting is presented in an analytical framework represented by the model that is judged suitable for assessing performance, effectiveness, and capability to enable decisions on improvements to the targeting system.

- A targeting model introduces a concise philosophy under which targeting should be conducted which is easily conveyed to practitioners and non-practitioners alike.

The targeting process

The US Joint Targeting Cycle provides the basis for the technique of targeting employed by both US and Australian militaries.7 The cycle is a process containing a series of procedural steps which, for reasons of utility, efficiency, command respon- sibility, and legality, must be followed. The targeting cycle — which includes all the elements of a generic targeting operation — has six components reflected in both US and ADF doctrinal publications, as outlined in Table 1.

The simplifications offered in ADF doctrine also provide a broadening of each component — primarily for assessment — which includes immediate combat assess- ment as well as broader capabilities assessment, campaign assessment, and lessons.

Representations

With the basic requirements and abstract procedure of targeting defined by the Targeting Cycle, different representations of the process are adopted for specific contexts. This article will focus on the most commonly used US and ADF approaches.

The US Army (and where appropriate the US Navy) makes use of the four-phase Decide, Detect, Deliver, Assess (D3A8) construct as the overarching approach to targeting, complemented by dynamic targeting constructs.9 In particular, these dynamic methods are useful to address gaps that exist in current doctrine and ensure the immediate relevance of the targeting process to current conflicts.10

While the Joint Targeting Cycle is applicable to targeting in all environments, US doctrine provides a specific land/maritime targeting approach. Table 2 describes the US Army doctrine definition of the elements of the D3A construct.

While basic and direct, the D3A concept meets tactical battlefield requirements by largely assuming a fixed and limited area of operations in which a commander has complete control of all assets. This construct has been used for targeting on all time scales until the advent of the F3EA model (with some incursions of air force doctrine into the dynamic targeting space).

The concept of dynamic targeting11 evolved in US and ADF doctrine throughout the 1990s and early 2000s to address specific concerns that emerged during targeting conducted within a compressed timeline.12 Dynamic targeting aims to focus targeting staff on those elements of targeting that are essential to actioning a target in minimal time while still meeting a commander’s responsibilities under the Rules of Engagement.13 F3EA has emerged as the current favoured dynamic targeting construct, following on from the find, fix, track, target, engage, assess (F2T2EA) model previously employed.

Table 1. Comparison of elements of the ADF and US Joint Targeting Cycles.

|

US |

ADF |

|

End Stateand Commander’s Objectives |

Commander’s Guidance |

|

Target Development and Prioritisation |

Target Development |

|

Capabilities Analysis |

Capabilities Analysis |

|

Commander’s Decision and Force Assignment |

Force Application |

|

Mission Planning andForce Execution |

Execution |

|

Assessment |

Assessment |

Table 2. Elements of the D3A targeting construct.

|

Decide |

Target categories identified for engagement |

|

Detect |

Targets areacquired and monitored |

|

Deliver |

Target is attacked in accordance with command guidance |

|

Assess |

Estimate of effect is compiled and reported |

Given its original development and primary use by the USAF, F2T2EA provides an air-centric approach to progress from command direction to validated target effect.14 Air targeting is inherently operational or strategic by nature (as opposed to largely tactical land-based targeting) and often requires the coordination of multiple assets with multiple ownership (or complicated command and control) across multiple areas of operation. F2T2EA assumes well-developed command guidance to initiate targeting and is designed to allow information to flow quickly between phases and functional areas within a targeting centre to meet the dynamic nature of the situation. The elements of F2T2EA are outlined in Table 3. During Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan in 2001, airpower was required to directly support Special Operations forces and undertake strike operations in response to swiftly shifting command priorities.15 The lack of flexibility in implementation of the targeting cycle and the lack of coordination between levels of command were key realisations — highlighted by the failure during Operation Anaconda to capitalise on terrorist targeting opportunities. Since 2001, combined air (ISR/strike) and ground force elements have been increasingly used to prosecute high value, low contrast, often mobile targets in complex environments. Operational observations relating to dynamic targeting have included a require- ment to synchronise ISR and all-source intelligence requirements and analysis, a need to access and process information at the lowest possible level, and a need to flexibly apply assigned assets. A key point is that different targeting concepts enable different operational capability. The execution of F2T2EA has been found lacking in two main areas: the speed at which the cycle can be executed, and the ability to accurately determine effects and outcomes to enable further dynamic targeting. Further, contemporary warfare poses new challenges in target selection in which targeting itself provides follow-on targeting opportunities. An extension beyond F2T2EA was deemed essential to address these concerns leading to the increasing adoption of the find, fix, finish, exploit, assess (F3EA) model.

Table 3. Elements of the F2T2EA construct.

|

Find |

The detection of an emerging target following clearcommand guidance to collect on named areas / targets of interest. |

|

Fix |

The positive identification of the targetas valid andthe generation of data with sufficient fidelity to permit engagement. |

|

Track |

Target position andtrack (if appropriate) maintained and desired target effects confirmed. |

|

Target |

The generation of engagement options for recommendation to a designated commander; the simultaneous resolution of restrictions and deconfliction issues. |

|

Engage |

Action against target to achievethe desired effect. |

|

Assess |

The measurement of engagement outcomes and effects on the target;may lead to re-attack recommendations. |

Elements of F3EA

F3EA emerged from the Afghanistan and Iraq wars as the de facto standard targeting approach for Special Operations units tasked with targeting insurgent networks. F3EA uses multiple feedback loops to simultaneously detect, stimulate, and discover the structure and nature of an adversary system. This feedback occurs through a combination of fast and slow loops following exploitation (fast) and analysis (slow). These loops enable one or more targeting cycles to immediately follow the ‘finish’ phase of a given target. In this way, F3EA is designed to enable organisational learning about the adversary and the environment. This approach is similar to the concept of adaptive action defined by the Australian Army in which an iterative process of discovery and learning facilitates adaptation.16 Similarities and differences in the two concepts are discussed later in this section.

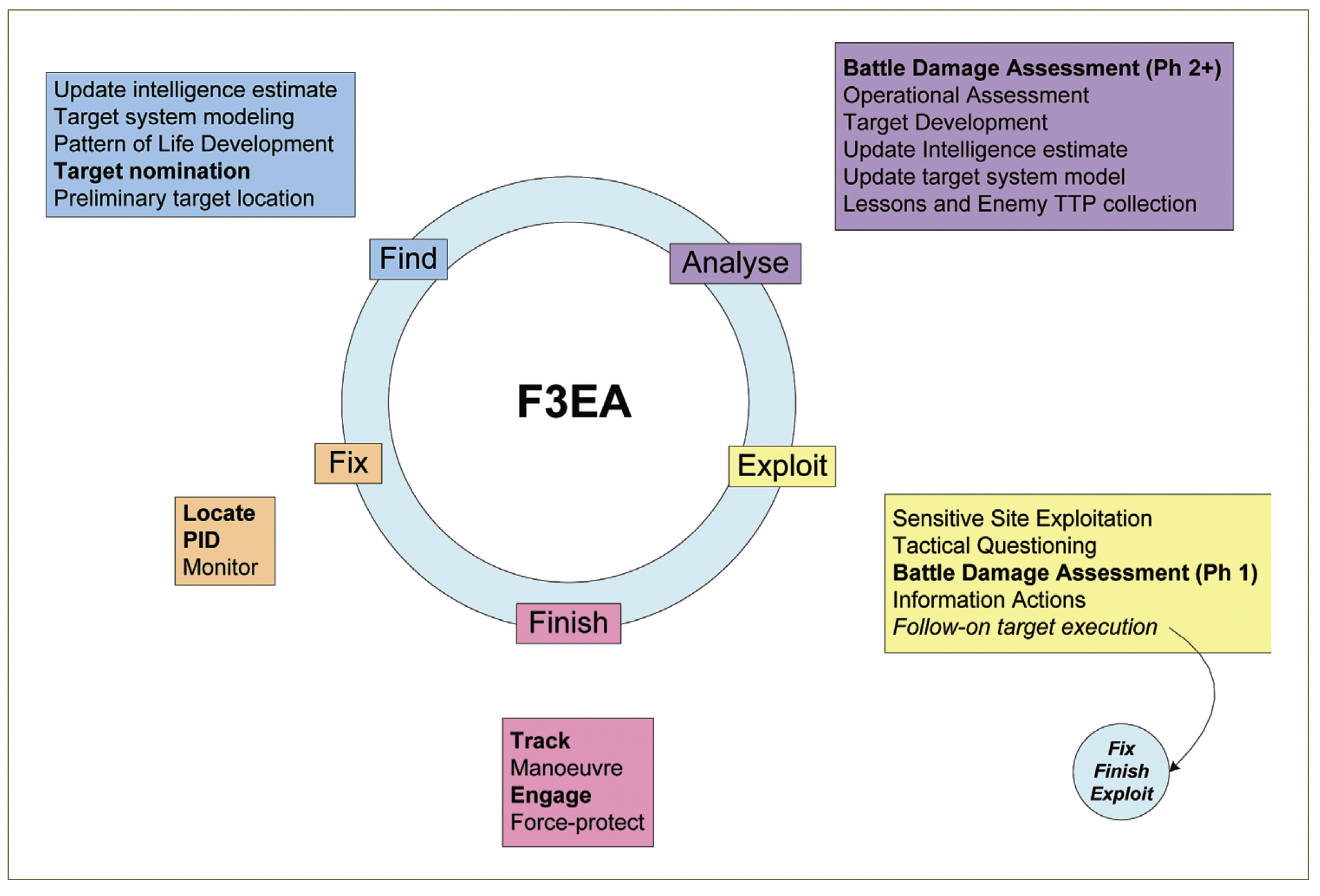

Figure 1 illustrates the way in which the elements of F3EA relate to specific tasks within a targeting cycle as practised in current operations. The elements of

F3EA are represented graphically with tasks and outputs expanded in detail in the following text.

The tasks and outputs associated with each of the F3EA phases are: find, fix, finish, exploit and analyse. They are explained in more detail in the following paragraphs.

Find describes the process through which targets and their elements are detected, modelled, and prepared. This phase includes the development of an intelligence estimate (to create a holistic picture for command staff — common forms include PMESII17 and ASCOPE18 analyses), target system modelling (identifying detectable and targetable system elements), pattern of life development, target nomination (detailed request to target execution authority — based on a ‘target pack’ including intelligence and analysis) and preliminary target location (used to trigger collection assets to locate and identify target elements).

Fix is the process which allows prepared targets to be identified, located, and monitored in preparation for actioning. This phase includes the generation of a precise location of target element/s in the battlespace, the positive identification of the target, and the maintenance of a track on the target. This phase also includes the continual update of situational awareness of the local area and detection of indicators and warnings of changes to the situation.

Figure 1. The F3EA concept represented as a cycle, with tasks and outputs of each stage defined. Bolded items are elements of the doctrinal targeting process. The exploit phase allows for an implicit branch to a second targeting operation, normally truncated to reflect opportunism.

Finish is the term describing the process by which targets are actioned to achieve the commander’s desired effect. During this phase a track is maintained on the target while execution assets are manoeuvred to engage the target. Engagement involves the execution of actions to create the desired target effect through kinetic or non-kinetic means.

Exploit describes the process by which opportunities presented by the target effect are identified and branch actions planned, often including the development of a follow-on targeting cycle. This phase includes Sensitive Site Exploitation (the collection of biometrics and physical samples of intelligence value from the target area and the investigation and documentation of the site), Tactical Questioning (gathering human information from persons in or around the target area), Battle Damage Assessment (the initial assessment and reporting of the quality of target effect and recommendations for re-attack), and Information Actions (to exploit the outcome of the finish phase and mitigate against operational risks that may arise due to collateral effects or adversary information actions). Information actions may take the form of messaging, leadership engagement, humanitarian, or other Psychological Operations or information operations capabilities.19

Analyse is that process within which detailed research and development is undertaken to restart the F3EA cycle, improve situational understanding, and improve own-system capability. This phase includes combat assessment (a detailed assessment of effects on the target system), operational assessment (an assessment of the outcomes of the operation in terms of the greater operational plan, producing recommendations for future target sets and apportioning of assets to meet changing operational requirements), and updating of the intelligence estimate and target system model. This phase also includes the development of new targets and may trigger a new targeting cycle. Finally, the analysis of own-force performance (lessons) and changes in adversary capability and effectiveness (enemy TTP) is completed to adapt own-force planning and counter possible future enemy actions.

Taken together, the find, fix, finish, exploit, analyse construct provides a method for dealing with high tempo operations against low-signature targets while focusing not only on the execution of the current target, but the generation of new targets. This recurrent action — based on the idea that, in modern warfare, complex systems often require some form of action in order to force target elements above the intelligence threshold — forms the point of difference between F3EA and earlier targeting paradigms.20

Characteristics of F3EA

The F3EA approach recognises that successful targeting in complex environments is heavily reliant on the exploitation of target and site information in order to facili- tate follow-on targeting. It also recognises that the detailed analysis of such informa- tion will provide a greater understanding of the adversary and the environment.21 The F3EA approach thus closely follows the complex warfighting paradigm and espouses two key principles. The first of these maintains that exploitation and analysis, if not the main effort of the targeting process, are the components that keep the process cyclic.22 The second principle is that modern warfighters must constantly interact with the changing environment in order to learn at the rate demanded by successful targeting operations.23

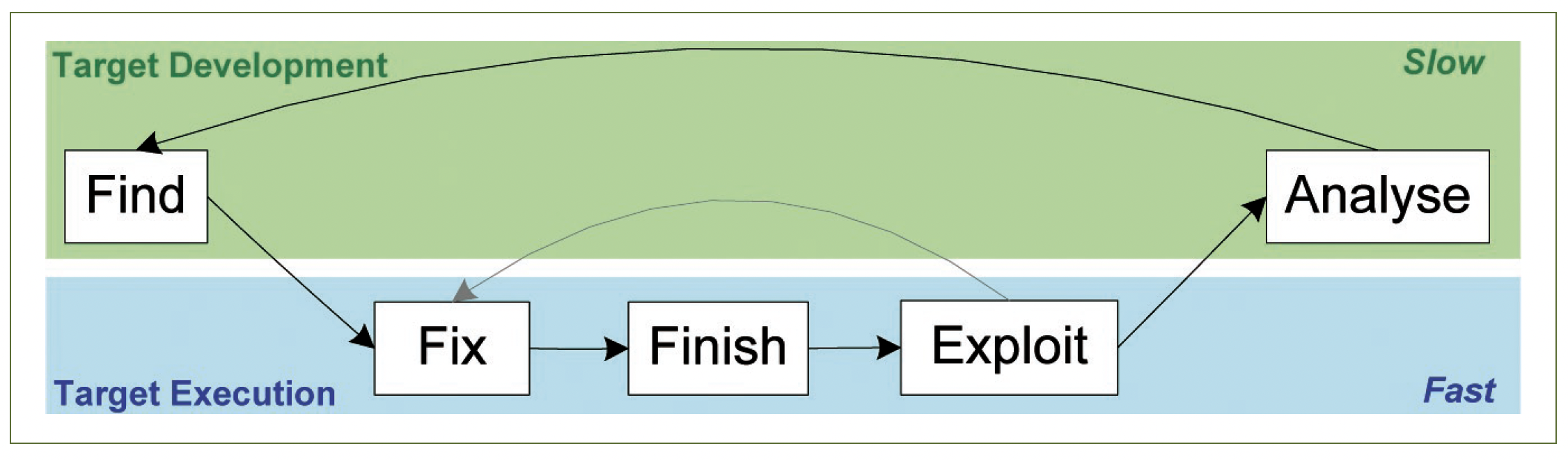

F3EA utilises a double feedback loop (fast/slow) to handle targets emerging at different rates, or targets which require different levels of devel- opment.24 The departure from traditional dynamic targeting approaches is represented by the addition of the ‘fast’ loop, which speeds responsiveness of the targeting system to targets which emerge during or as a direct consequence of a targeting action. For example, tactical questioning of an insurgent may reveal the location of others resulting in the requirement to prosecute quickly while the information remains relevant. The ‘slow’ loop makes allowance for more traditional analysis-based target development and execution. This is described in Figure 2, where target development (which may take from days to months or years) is contrasted with the high tempo target execution component, which normally occurs very rapidly and can generate an entirely new target set that itself requires immediate, rapid execution.

F3EA assumes limited knowledge of the target (adversary or threat) system and thus relies not on a comprehensive model of the system during targeting, but rather on an emerging understanding of the system during recurrent F3EA cycles. Such intelligence-led targeting differs from operations-led targeting by the simple qualifier that the information feeding the targeting process is predominantly sourced from intelligence cells or ISR assets in real or near-real time.25

Michael T. Flynn, former intelligence chief for the International Security Assistance Force — Afghanistan, explains the current F3EA approach in the Afghanistan context with the observation that ‘exploit-analyze is the main effort of F3EA because it provides insight into the enemy network and offers new lines of operations.26 This concept aligns closely with the Australian Army’s ASDA construct which is designed specifically to counter low-signature adversaries.27 The assumption that most of the target system exists below the intelligence (detection or discrimination) threshold is matched with the hypothesis that, by perturbing the target system, some target elements must necessarily respond, thus providing a signature that can be detected, analysed, and turned into intelligence concerning the target system.

The Australian Army’s Adaptive Campaigning concept proposes ‘interaction with the problem’ as a key element of the planning and execution of operations in a complex environment.28 Interaction with the problem, through action, subsequent discovery and learning, allows the problem to be better defined (akin to the ‘slow’ F3EA loop) while behaviour is changed (representing an additional, slower loop that is not a component of targeting, but of planning). Changing the problem frame through iterative adaptive action and learning is a more general aspect of changing the adversary (target) frame through iterative action, exploitation and assessment in a targeting cycle. In this sense, the Adaptive Campaigning model can be viewed as a general operational level construct within which the F3EA targeting model neatly fits. The key difference is specificity of purpose: F3EA exists to neutralise or destroy an adversary, while Adaptive Campaigning exists to support general purpose land forces in the conduct of joint operations.

There has been increasing recognition of the requirement to maintain a reactive targeting capability across the services in both Australia and the US. The respective air forces have focussed on the ‘sensor-shooter’ link, reducing the system constraints on tempo for the find-fix-finish component of the cycle.29 This need to improve system capability to complete the targeting loop quickly is, to some degree, guiding future force design and capability acquisitions and partially explains the huge increase in non-traditional platforms.30

Figure 2. The F3EA model can be separated into two elements: target development and target execution. The full F3EA cycle can be truncated to incorporate just the ‘fast’ elements (fix, finish, exploit) in highly dynamic targeting environments where target exploitation immediately leads to the presentation of new targets.

F3EA in modern campaigns

The focus of contemporary dynamic targeting is insurgent network interdiction, specifically the targeting of high and medium value individuals. The targeting of individuals combines a classic low-signature, transient target with a high collateral effect risk and very high intelligence burden.31 The Bin Laden raid is an excellent example of such an operation.32 When coupled with a low force footprint and relatively low availability of collection, manoeuvre, and action assets, this has effec- tively pushed targeting elements into a paradigm which forces adversary systems to change and react to changes in the system.33 The discussion of current applications of F3EA in the next section is based on the assumption of these concepts.

The great strength of the F3EA model is the level of centralised control it affords through the use of organic assets.34 This approach also produces an inherent weakness, namely the huge consumption of resources — particularly ISR assets — and concentration of these resources in a targeting agency that may operate on only one of the multiple operation lines simultaneously occurring in a modern conflict. This ‘opportunity cost’ is a trade-off that must be considered when designing force structures and command and control arrangements in modern warfare.35

The detection of the target occurs in two parts: find and fix. Find includes the determination that a target exists and can be accessed. This phase includes deeper analysis to determine the location of the specific target under consideration within the larger target system. The fix phase aims to determine a time and location for target engagement while validating the target to enable the finish step to commence.

The assess function is similarly extended to include exploit and analyse.36 These two steps are linearly linked but maintain two different priorities. Exploit is concerned with immediate collection and analysis of information to enable rapid follow-on targeting and area effects to be generated. Analyse takes the informa- tion gained during exploitation, plus other sources of intelligence, to determine outcome effects, create new intelligence about targets or the environment, discover new targets for development, and share this information with other battlespace users. A further aspect of the analyse phase is self-analysis — the assessment of own-force performance and effects for the purpose of operational learning. The primary purpose of the exploit phase is to provide information-led operational branch options that may be pursued in line with command guidance.

Limitations of F3EA

In assessing the limitations of F3EA, it must be noted that this approach is not optimised for a conventional ‘first three days’ of warfare. In the early phases of conventional campaigns, targeting activities are largely driven by the operational level TSA, leaving little opportunity to dynamically engage or exploit target effects outside the fixed plan. Operation Odyssey Dawn, the 2011 Libyan interdiction, provides an illustrative example in which initial targeting focused on known counter-air and counter-sea infrastructure. Dynamic targets did not become a focus until the air defence system had been (at least partially) dismantled.37

F3EA may not be appropriate for conventional industrial targeting, apart from those occasions when dynamic targets occur. The concept of ‘exploit’ loses meaning in this context and becomes merely the first phase of analysis. In conventional targeting, a large proportion of time is spent in acquisition and tracking, while the ‘finish’ component is normally rapid. For example, the location and tracking of mobile air defence systems is taxing on ISR systems, with bomber aircraft held on standby; the finish is actioned as soon as a fix is achieved.

F3EA assumes a force structure and resource availability that is specific to forces designed for targeting — namely, significant ISR assets, a large analytical capability, and a rapid and highly reactive finish capability. This use of assets — organic or shared — is not necessarily the most efficient allocation across all lines of operation as an increase in effectiveness in finding and actioning targets comes at the cost of a sub-optimal resource allocation. This concept is well articulated by the US Asymmetric Warfare Group which observes that ‘the benefit of utilising F3EA … is that it refines the targeting process to identify and defeat specific indi- viduals. A potential down side to this approach is focussing critical collection assets on targets that are at the lowest level and not focussing assets against networks.’38

Current use of F3EA by the ADF is hamstrung by the lack of analytical capacity to fully implement the exploit and analyse phases. Contemporary operations are typified by the presence of ‘wicked’ problems, fitting the general definition of unknowable and un-testable, unique and ‘one-shot-only’ solutions.39 Targeting via the F3EA method is a direct and expedient method of treating these problems. However, without appropriate analytical capability, the application of F3EA may lead to the repetitive treatment of symptoms rather than allowing the systematic interdiction that targeting complex networks requires. In modern operations where forces are engaged in a race to learn and adapt, the risk is not only in being too slow, but also in learning the wrong things.

Conclusion

F3EA is the product of an evolution of traditional targeting concepts designed to allow targeting elements to compete with adaptable adversaries in complex environments. It is well suited to this particular challenge; when applied by appropriately enabled forces, F3EA has been shown to be highly successful.

The examination of F3EA and the way targeting framing has changed invites reconsideration of the purpose and desired outcomes of targeting actions. By embracing a construct that is inherently reactive such as F3EA, there is a tacit acknowledgement that our ability to understand the environment and the actors within it is insufficient to allow us to gain and maintain the initiative in contemporary conflict — contrary to the general aim of military targeting. This dilemma can be resolved with a reconsideration of purpose — the purpose of targeting in a complex environment should be to gain and maintain initiative within the conflict.

Where initiative requires understanding, learning is key. Targeting is used now not merely to neutralise threats or prepare the operational environment, but to learn about the adversary. Whereas learning had previously been a means to an end (to enable a strike), it is now an end in itself. What targeting achieves has changed, bringing opportunities and threats related to the dual outcomes. Targeting in a complex environment invites a tension between learning in order to affect and affecting in order to learn.

This highlights the difficulty of selecting targets and effects in an environment in which the true nature of a targeted system is unclear — or swiftly changing. Another view regards operations as an asset allocation problem, and the science of command as determining an allocation that can achieve multiple and sometimes conflicting priorities; in this sense, the F3EA representation simplifies the targeting problem.

Modern conflict requires a targeting philosophy that can respond very quickly to changes in the environment, maximise the collection and exploitation of available information, and maintain simultaneous streams of target development and execution at tempos dictated by adversary operations. Warfare against conventional adversaries will continue to leverage the efficiency and centrally prioritised effects at the joint operational level offered by the standard targeting approach.40 Future conflicts will use a combination of targeting approaches optimised to the types of warfare, forces, and adversaries within the conflict environment.41 Given the environment forecast in the Australian Army’s complex warfighting concept, F3EA will play a role in which dynamic and adaptable targeting actions are required.42 It now remains for doctrine and training to recognise and reflect the full potential of the F3EA approach.

Endnotes

1 For discussion of this concept, see R. Smith, The Utility of Force: The Art of War in the Modern World, Knopf publishing, UK, 2007.

2 M.T. Flynn, R. Juergens and T.L. Cantrell, ‘Employing ISR: SOF Best Practices’, Joint Force Quarterly, Third Quarter 2008, p. 56, retrieved on 7 December 2010 from http://www.dtic.mil/doctrine/docnet/courses/intelligence/intel/jfq_50_a…

3 Australian Defence Doctrine Publication (ADDP) 3.14, Targeting, Land Warfare Development Centre, Puckapunyal, 2009, para. 1-3.

4 Ibid., para. 1-4.

5 This concept of opportunity relates to the discovery mechanism of the target rather than to the importance (or necessity) of action against the target.

6 While abstract models can be considered as processes — taking inputs, transforming them, creating outputs — the idea of ‘process’ is too often tied to a rigid adherence to step-wise procedure; the concepts are separated here to avoid confusion.

7 US JP 3-60, Joint Doctrine for Targeting, 13 April 2007; ADDP 3.14, Targeting.

8 US FM 3-09.12 Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures for Field Artillery Target Acquisition, 21 June 2002.

9 D3A is used in deliberate targeting — targeting that will be planned when operational planning is underway. Dynamic targeting constructs are used when targeting must be planned during operational execution.

10 While the methods do not modify the steps of the targeting process, the method or approach frames the way the process is executed. See D.N. Propes, ‘Targeting 101: emerging targeting doctrine, Fires’, March 2009, retrieved from http://www.

thefreelibrary.com/Targeting+101%3A+emerging+targeting+doctrine.-a0200920409 on 7 December 2010.

11 The concept of dynamic targeting is largely artificial in the contemporary context, relating not to the properties of the target but instead to the way it is treated within the battle rhythm of a targeting force. The concept is more relevant to air operations (where processes are established to service a known target list) than land operations (which possess largely asynchronous targeting processes).

12 Specifically in ADF doctrine — ADDP 3.14 Targeting.

13 And ultimately the Laws of Armed Conflict.

14 That is, optimised for a centralised control, decentralised execution model as opposed to fully decentralised models favoured by land forces. See (US) Air Force Doctrine Document (AFDD) 2-1.9, Targeting, 8 June 2006.

15 B. Lambeth, Airpower against Terror: America’s Conduct of Operation Enduring Freedom, RAND Corporation Monograph, 2005.

16 Adaptive Campaigning 09 - Army’s Future Land Operating Concept, Directorate of Future Land Warfare, Canberra, 2009.

17 Political, military, economic, social, infrastructure, information.

18 Areas, structures, capabilities, organisations, people, events.

19 In ADF doctrine psychological operations are a component of information operations. See ADDP 3.13 Information Operations, Land Warfare Development Centre, Puckapunyal, 2006.

20 The intelligence threshold is a simplification of the ‘ISR threshold’ concept which recognises that targeting in the contemporary sense is led by intelligence which is a product of analysed information, and not by ISR data or information.

21 More importantly, the difficulty in separating the adversary from the environment

22 Flynn, Juergens and Cantrell, ‘Employing ISR’, pp. 56–61; W.J. Hartman, Exploitation Tactics: A Doctrine for the 21st Century, School of Advanced Military Studies Monograph, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, 2008, p. 20.

23 J.D. Deeney, Finding, Fixing, and Finishing the Guideline: The Development of the United States Air Force Surface-to-Air Missile Suppression Force During Operation Rolling Thunder, Masters Thesis, US Army Command and General Staff College, Kansas, USA, 2010.

24 Either due to the complexity of the target or due to development that may have already occurred.

25 Real or near-real time as defined by the local commander on the basis of tactical developments or by operations using baseline (non-real time) intelligence.

26 Flynn, Juergens and Cantrell, ‘Employing ISR’.

27 Act-Sense-Decide-Adjust. See Adaptive Campaigning, p. 31.

28 Ibid., p. 33.

29 For a discussion of the concept of a ‘hunter-killer’ architecture for the USAF, see

D. Deptula and M. Francisco, ‘Air Force ISR Operations – Hunting versus Gathering’, Air and Space Power Journal, Winter 2010, pp. 13–17, at: http://www.airpower.au.af. mil/airchronicles/apj/apj10/win10/2010_4_04_deptula.pdf

30 Particularly armed unmanned aerial vehicles.

31 This includes the requirement to collect evidence of enemy or criminal activity to enable nomination of an individual as a target.

32 For details of the raid, see http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2021260/Osama-

Bin-Laden-Full-details-raid-catch-Al-Qaeda-leader-know-SEALs-identity.html accessed 20 February 2013, or the fictionalised account in the popular film Zero Dark Thirty.

33 Small footprints lead to discontinuous battlespaces where large areas within the terrain have little or no friendly force presence and can be considered non-permissive.

34 For an expansion of this concept in the Iraq context see W. Rosenau and A. Long, The Phoenix Program and Contemporary Counterinsurgency, Occasional Paper, RAND Corporation, 2009, at: http://www.rand.org/pubs/occasional_papers/2009/ RAND_OP258.pdf

35 Propes, Targeting 101: Emerging Targeting Doctrine usefully deconstructs the F3EA process for comparison with D3A.

36 Some proponents add disseminate to create F3EAD; dissemination can also be included in the analyse step.

37 Details of first-day targets are available via U.S. AFRICOM Public Affairs (20 March 2011). Overview of 1st Day of U.S. Operations to Enforce UN Resolution 1973 Over Libya. US AFRICOM, available from 19 Feb 13 at http://www.africom.mil/ NEWSROOM/Article/8097/overview-of-1st-day-of-us-operations-to-enforce-un

38 Attack the Network Part 1: Oil Spot Methodology, US Asymmetric Warfare Group, March 2009, retrieved on 10 December 2010 from: http://info.publicintelligence.net/ ArmyAttackNetwork1.pdf

39 For an introduction to ‘wicked’ problems, see H. Rittel and M. Webber, ‘Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning’, Policy Sciences 4, Elsevier Scientific Publishing Co., Amsterdam, 1973, pp. 155–169.

40 In a ‘target rich’ environment.

41 For a discussion of the concept of hybrid warfare — a combination of asymmetric and conventional conflict — see F.G. Hoffman, ‘Hybrid Warfare and Challenges’, Joint Forces Quarterly, Issue 52, First Quarter 2009, pp. 34–39; M. Isherwood, Airpower for Hybrid Warfare, Mitchell Paper 3, Mitchell Institute for Airpower Studies, June 2009.

42 Or this role may be filled by an evolved version of the F3EA concept.