Abstract

The RAA role in Afghanistan provided an opportunity to demonstrate and refine the artillery capability after decades of doubt over its future. Its Afghanistan experiences have enabled the RAA to evolve, refining, enhancing and reinforcing what is a crucial role. With the imminent conclusion to the Australian commitment in that theatre, the RAA will reconstitute and reorientate towards providing an invaluable capability for Army in future conflicts; this capability, however, may be entirely different to that required during its most recent deployments. Indeed the artillery capability of 2020 will be unique, merging the mutually supportive functions of JFE, air-land integration, GBAD, battlespace management, sensor fusion, ISTAR collection, processing and dissemination, artillery intelligence and support to joint targeting. Achieving this future artillery capability will require appropriate artillery major systems, realistic and pervasive collective training of all the artillery streams, and the inherent flexibility of gunners as an organisation. There will be significant risks and challenges in achieving the artillery capability of 2020, but it must remain the focus of every gunner to meet those challenges and increase the capability of the Royal Regiment for years to come.

Introduction

Three brave men who do not know each other will not dare to attack a lion. But three men, knowing each other well, sure of their reliability and consequently of their mutual aid, will attack resolutely.

- Colonel Charles Ardnant du Picq, 1880

With the Australian Defence Force (ADF) presence in Afghanistan having reached its culminating point, the impending withdrawal of its deployed fighting force has generated a number of strategic policy reviews into the suitability of Defence capabilities for future conflicts across a broad spectrum of demands. Critically for the joint domain, the ADF has sought resolution of lessons learned in precision targeting and engagement, force protection, collateral damage minimisation and persistent battlefield surveillance and target acquisition. Though by no means exclusively responsible for the provision of these functions, the capabilities of the Royal Regiment of Australian Artillery (RAA) represent a key microcosm of this strategic concern.

With a view to capability development for the achievement of Objective Force 2020, the RAA finds itself at the cusp of a technological advent that will see it reaffirm its position as a critical force multiplier in the modern complex battlespace. This article will examine the RAA’s development of capability during the Afghanistan conflict, discuss the attributes that characterise the RAA’s unique contribution to the ADF’s fighting power, and outline the training focus and future combat needs of the RAA under the multi-role combat brigade concept of Plan Beersheba.

CONTEMPORARY WARFIGHTING AND THE RESURGENCE OF ARTILLERY

In the period that spanned the Vietnam and Afghanistan conflicts, the RAA was downsized, neglected and misunderstood. The commitment of the Australian Regular Army to Afghanistan presented a valuable opportunity for the RAA to demonstrate the capability of artillery. As the commitment progressed, all three streams of the RAA — joint fires and effects (JFE), surveillance and target acquisition (STA) and air-land integration — were deployed in role to Afghanistan. Given the requirement to rapidly adjust to the contemporary operating environment, all three streams were modernised and re-equipped to fill some aspects of their artillery role in Afghanistan. Before long, the RAA was able to demonstrate its relevance to the other corps, to Defence, to the government and to the taxpayer. As the RAA gained experience with its modern equipment, more opportunities emerged to expand the overall artillery capability. Deployment to Afghanistan allowed the RAA to display elements of its capability, to re-equip, to refine the way it achieved its capability and to again prove its potential on the battlefield.

Considering the dramatic shift in RAA capability and focus as a result of the ADF commitment to Operation Slipper, it could be reasonably argued that Afghanistan saved the artillery capability. Paradoxically, however, the employment of artillery in Afghanistan has merely scratched the surface of its future capability. While the achievements of the Australian gunners in Afghanistan have won plaudits both domesti- cally and internationally, the lessons learned from this experience must now refocus the ADF’s vision to reflect the potential of the RAA. Future conflicts will require the RAA to provide capability above and beyond that demanded in Afghanistan.

AFGHANISTAN AS A CATALYST FOR CAPABILITY DEVELOPMENT

The RAA is Army’s key provider of tactical offensive effects through the delivery and coordination of JFE, STA and ground-based air defence (GBAD). While each of these capabilities is unique in itself, their integration under the parent banner of the RAA has proven exponentially more potent, efficient and effective. Perhaps more interestingly, the deployment of the three RAA capabilities to the Afghanistan campaign has further served to reinforce both the efficacy and requirement for integration of the RAA in the joint environment.

The planned scaling-back of Australia’s military presence in Afghanistan has been a catalyst for revisiting the 2009 White Paper and considering how extant and future policy will be executed by a future land force. At both the tactical and operational level, the Afghanistan experience has provided the RAA a springboard from which to develop a three-pronged capability complementary to future operating concepts.

JFE

The offensive support capability of the 1st, 4th and 8th/12th Regiments has predominately centred on the joint fires team (JFT) and Joint Fires and Effect Coordination Centre (JFECC) models of support to manoeuvre operations at sub-unit and unit level respectively. From a tactical perspective, the JFTs deployed to Operation Slipper have filled their traditional role — to provide joint fires and effects advice, liaison and communications to a supported combat team; to coordinate and deconflict the employment of JFE; to implement the combat team battlespace management plan; and to engage targets within their zone of observation with JFE assets.1 The JFTs have provided a joint coordination and strike option for manoeuvre operations at the tactical level without significant change to their habitual tasks.

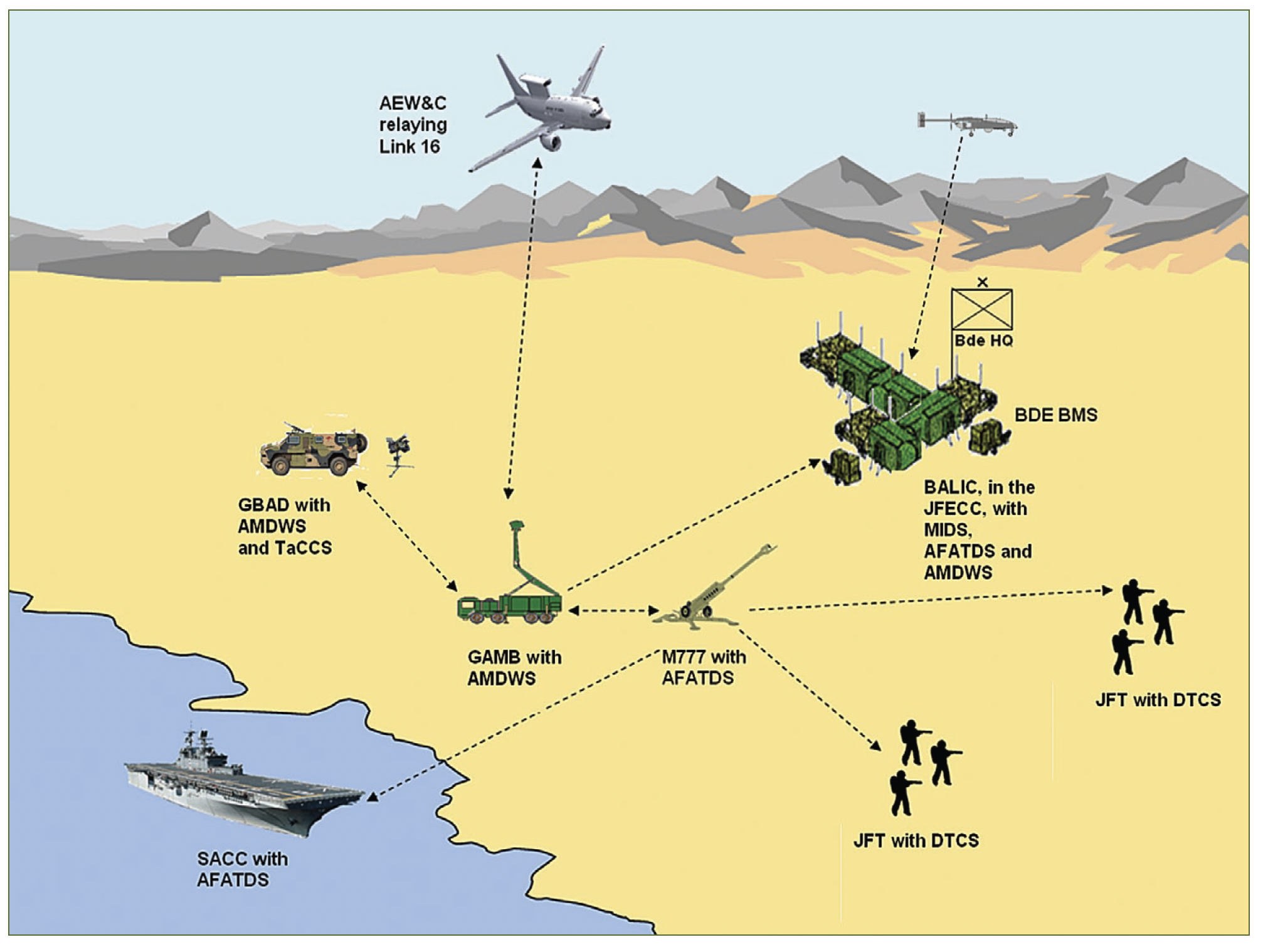

Figure 1. Interoperability of the RAA in the joint battlespace

At the operational level, however, there has been considerable reform across the regiments to generate JFTs of sufficient training and flexibility to withstand the rigorous demands of the contemporary battlespace. As each JFT is potentially responsible for the simultaneous control of multiple close air support and indirect fire missions from artillery and mortars, the gun regiments have remodelled their trade structure and aptitude requirements at recruiting levels to ensure that the right soldier is employed in the appropriate trade category. Furthermore, the gun regiments temporarily adopted a unit order of battle that grouped their JFTs in modular batteries. These batteries could then be trained and deployed without interruption to the conventional warfighting training program of the remainder of the regiment.2

Finally, in order to provide sufficient joint terminal attack controllers (JTACs) to enable terminal attack control authority at combat team level, the RAA has implemented a process of mentoring and screening suitable candidates across all ranks. This is a development that has seen a significant capability increase and which has subsequently been adopted across the ADF.3 These three RAA adjustments have ensured the success of the joint fires contribution to Army’s commitment to Afghanistan.

GBAD, sense, warn and locate, and air-land integration

The need for force protection in Afghanistan, specifically against surface-to-surface fires, provided a valuable opportunity for the deployment of 16 Air Land Regiment. The rapid acquisition of cutting-edge radar technologies has enabled 16 Air Land Regiment to provide force protection measures to deployed troops, enhanced its ability to provide a local air picture, and increased its capacity for a future ground- based air and missile defence capability. The radar support provided by 16 Air Land Regiment assisted in the identification and detection of surface-to-surface fires launched against Australian static positions, providing vital seconds of early warning to those manning these positions. The nature and frequency of such attacks provided the gunners from 16 Air Land Regiment the opportunity to develop tracking procedures and to upgrade hardware to counter the existing indirect threat while also honing their flexibility to meet a variety of future threats.4

The adoption of ‘soft’ defensive measures such as the Giraffe Agile Multi-Beam Radar, Lightweight Counter Mortar Radar and wireless audio-visual emergency systems has strengthened the ‘hard’ defences surrounding the Australian bases in Afghanistan and contributed to the preservation of Coalition lives. These assets were procured and introduced into service while on operation, providing them with immediate combat relevance as well as utility for future employment in a myriad of operational settings.

STA

The 20th STA Regiment has provided tactical STA support to conventional and special operations during Australia’s commitment to the Middle East Area of Operations through the employment of weapon locating radar and artillery intelligence and, since 2007, unmanned aerial system support to manoeuvre operations.5 Since the introduction into service of the Scaneagle unmanned aerial system, the deployed elements of 20 STA Regiment have increasingly found themselves at a premium for the provision of real-time battlefield surveillance and support to joint targeting.

The employment of unmanned aerial systems in recent operations has required significant integration with other airspace users and control agencies, ultimately resulting in the development of and improvement in joint operating procedures. In addition, through its exposure to supported agencies in an operational setting, the unmanned aerial system capability has earned its place alongside fixed and rotary- wing assets as a critical force multiplier for increasingly complex operations. This interaction has undisputed value for Army’s understanding of the joint battlespace and has positioned 20 STA Regiment for future capability development to capitalise on the crucial lessons learned during the past decade of continuous operations.

It is no coincidence that Army’s unmanned aerial systems capability has developed so swiftly; the complexity of the contemporary battlespace has demanded this. Over the course of the ‘evolution’ of unmanned aerial systems, Army has transitioned from the use of lightweight, low-endurance platforms capable only of intermittent, poor quality video downlink to vastly superior platforms capable of extended aerial patrols and high fidelity full-motion video. With the inclusion of technology allowing downlink to widely used situational awareness tools such as the Remote Operator Video Enhanced Receiver suite, this capability has proven its utility in assisting tactical commanders with the planning, execution and management of manoeuvre operations.

While the provision of full-motion video is an increasingly utilised feature of unmanned aerial systems, technological advancements focusing on the development of alternative payloads are increasing its potential combat support utility exponentially. Driven by the requirement for readily available, multiple-source intelligence collection sensors, this research is ultimately expected to facilitate accurate and reliable cross-cueing of electronic and visual payloads on a single platform. Combined with the ability of some unmanned aerial systems (in certain deployable configurations) to be controlled remotely from a forward ground control station, the next generation of unmanned aerial systems will afford supported commanders an unparalleled appreciation of the tactical battlespace.

THE UNIQUE CAPABILITY OF THE RAA

Consideration of the RAA capability beyond Afghanistan necessarily involves some discussion of the tactical options that artillery provides to commanders. In the past it has been argued that the RAA shares many of its principal functions with other corps. In particular, a crossover of functions appears to exist in the provision of indirect fire, ground-based reconnaissance, aerial surveillance and the coordination of strikes from aerial platforms. A commonly held view is that long-range target engagement with the in-service howitzer constitutes the limit of the RAA’s capability. While the artillery purist may nod in concurrence, this misconception ignores the capability evolution within the RAA that has rendered it unique and subsequently so crucial to the contemporary battlespace.

Four functions, one regiment

The historic capacity of the RAA to provide fire supremacy on the battlefield has not been lost. Rather, it has been refined, enhanced and supported by effect- multiplying technologies that have resulted from the RAA’s necessary adaptation to the current operating environment. The result is a corps which specialises in the integration and synchronisation of JFE, intelligence, surveillance, target acquisition and reconnaissance (ISTAR) and GBAD sensor-actor suites, targeting and artillery intelligence and battlespace management and coordination. These functions provide tailored and wide-ranging effects, from precision strike to massed fire, across a broad range of complex targets and tactical scenarios. While other corps may perform similar functions, the intrinsic requirement for integration to multiply the effects of any one individual function — the artillery modus operandi — makes the RAA’s understanding, execution and capability more complete and ultimately unique.

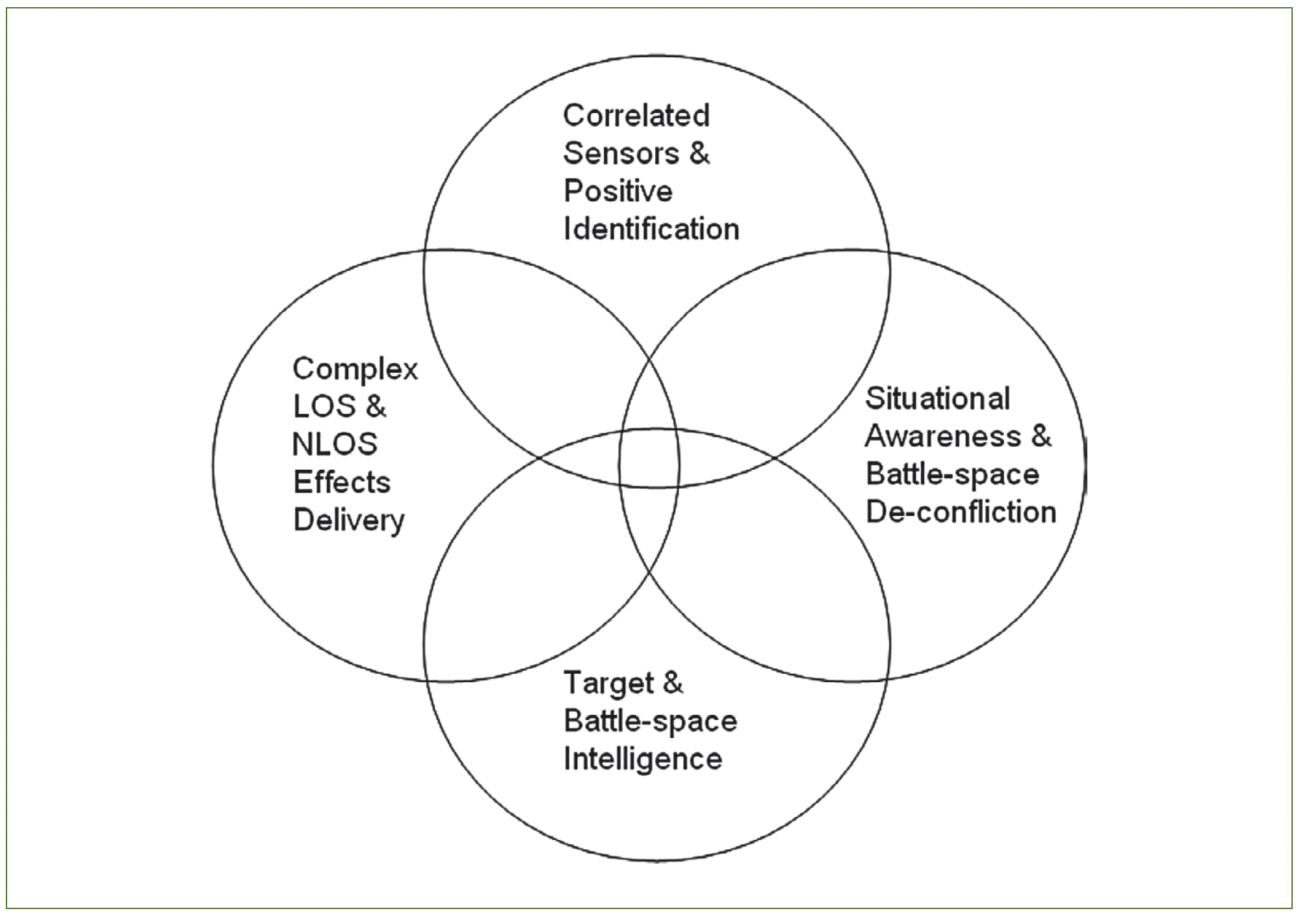

Figure 2. All four one, one four all — the key functions of the RAA and their relationship

The strategic policy of decades past has explored the possibility of ‘outsourcing’ RAA capabilities to other corps and services operating along similar functional lines. While the relevance of the RAA has been hotly debated, the ultimate decision to retain the identity, skills and attributes of the artillery has proven the right fit for the execution of modern warfighting. This is largely due to the acquisition of new enabling technologies, the modernisation of existing technologies and adaptation of their use to suit a multitude of operational roles. This flexibility relies not only on a detailed understanding of equipment but also the key functions that contribute to the overall artillery capability. These functions are not unique to artillery, but require an integrated approach to their execution that is unmatched by any other combat organisation.

The contribution of the three branches of artillery to the achievement of an integrated, functional capability is illustrated in the following hypothetical counter- insurgency scenario:

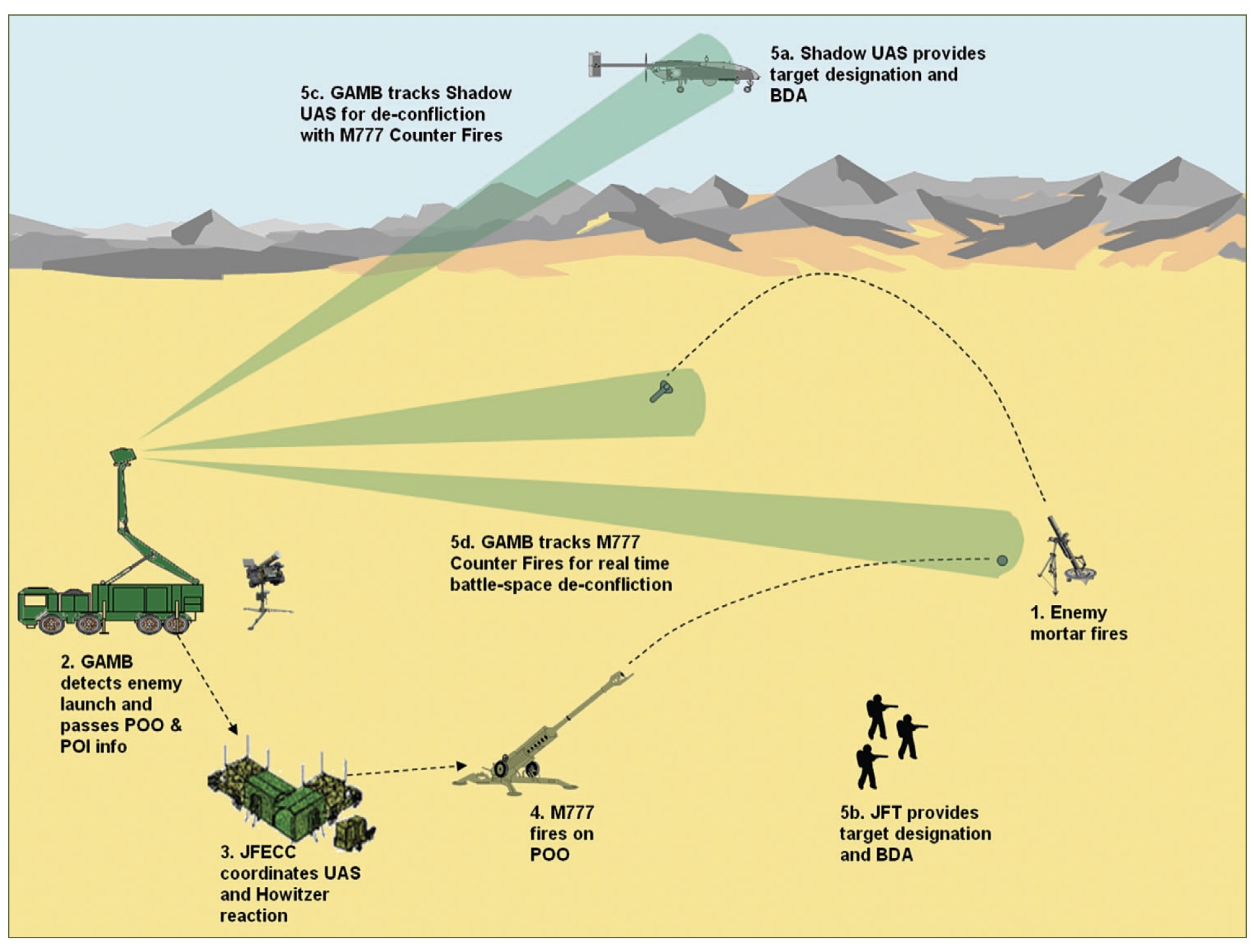

- A jamming strobe is detected by gunners of the Air Land Regiment. By manipu- lating the thresholds and operating parameters of their sensors to overcome the jamming, the source is isolated, recorded and exploited to build an electronic intelligence picture of the battlespace. The gunners work closely with other elements of the brigade collection plan, feeding the brigade intelligence staff. The source of jamming becomes a target and is passed to the JFECC for addition to the target nomination list for future engagement, but is assessed as a preliminary operation for a hostile fire mission.

- A mortar engagement by a previously undetected enemy indirect fire unit is tracked by the Air Land Regiment’s weapon locating sensors. Automatic extrapola- tion of the likely point of impact determines that the round will land in a friendly force location, cueing an audible and visual warning for all friendly personnel within the danger radius, warning them to take cover. From the information provided by the lightweight counter mortar radar, a point of origin is established, facilitating the cross-cueing of unmanned aerial systems to the target location. The operations and intelligence staff confer and agree to move the unmanned aerial system off its current collection task and onto this new dynamic task.

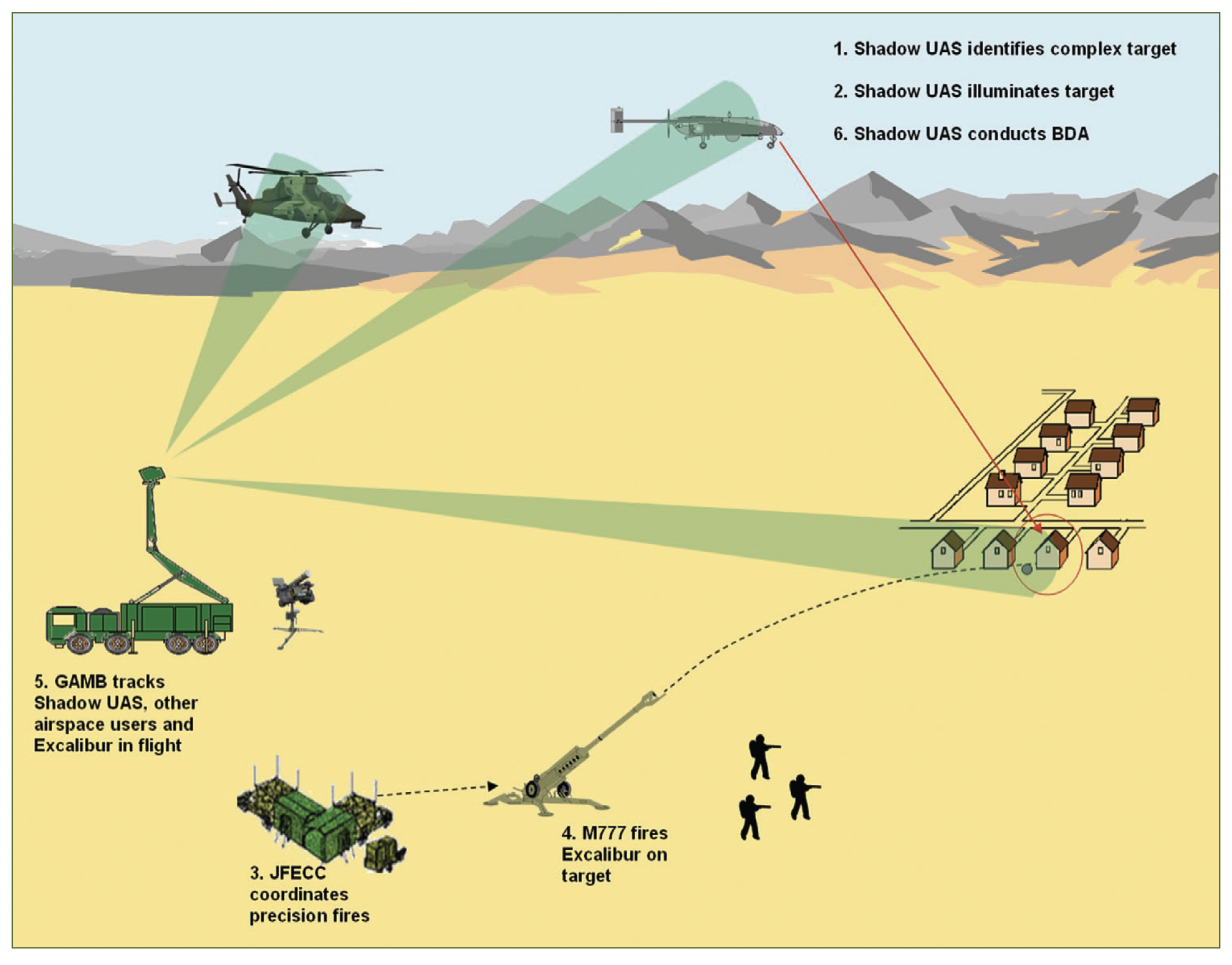

- On reaching the point of origin site, the unmanned aerial system observes a mortar baseplate with a three-man team firing on the friendly location. The brigade commander and operations officer consider their response options and agree that the JFECC can coordinate a JFE solution. Using target information from the unmanned aerial system via a remote operator video enhanced receiver downlink, a JFT moves into position to visually observe and positively identify the target. As a result of collateral damage estimate modelling, the forward observer commanding the JFT determines that engagement by conventional munitions is unsafe and that engagement by precision-guided ordnance or terminally controlled close air support will be required.

- Through the JFECC, the JFT provides local deconfliction for nearby air and land assets in preparation for target engagement and establishes the requisite control measures. With troops also in contact in another part of the area of operations, no close air support platforms are available to engage the mortar baseplate. The JFT orders a fire mission from his M777 howitzer battery and, just as they are about to engage, the Giraffe Agile Multi-Beam Radar detects a friendly helicopter transiting through the restricted operating zone. This results in a temporary pause in the engagement while communication is established with the aircraft. During this time, the hostile mortar team has managed to disassemble the baseplate and begins moving away from the site.

- The unmanned aerial system tracks the mortar team to a small compound eight kilometres west of the initial point of origin where the team halts and enters the building. Target information is passed through the JFECC to a nearby infantry company which is assigned to interdict the enemy. As the infantry company moves into position it is engaged from inside the building with accurate small arms and rocket-propelled grenade fire. The infantry company’s JFT, coordi- nating with the JFECC for a handover of engagement authority from the initial JFT, cues a precision fire mission on the target given continued collateral damage limitations. Once cleared for engagement, the target round is observed by the JFT which watches as the compound and the mortar team are destroyed.

- A battle damage assessment provided by the unmanned aerial system reports that one of the three members of the mortar team has survived the attack and is fleeing the compound. Observing the event via a remote operator video enhanced receiver terminal, the forward observer commanding the JFT requests the unmanned aerial system to track the suspected insurgent while the infantry company exploits the target location. As the insurgent flees the scene, another two enemy combatants are observed moving into an adjacent compound carrying what appears to be a long-barrelled weapon. Unable to maintain contact with the unmanned aerial system as it is now tracking the fleeing combatant, the JFT requests support from a helicopter while the remainder of the team tracks the target with binoculars. Shortly after arriving on station, the pilot is guided onto the target and reports that he has sighted the long-barrelled weapon. Once the forward line of own troops is verified, the joint terminal attack controller clears the helicopter for engagement resulting in the destruction of the target combatants with minimal effect on neighbouring compounds.

Figure 3. The tactical interrelationship of RAA elements

Figure 4. Locating, identifying and prosecuting targets with RAA elements

This scenario clearly demonstrates how the four key functions of artillery can be combined to create a unique capability with significant utility for operations well into the future. While the experiences and capability surges that resulted from counter- insurgency operations in Afghanistan were enormously beneficial for the RAA, these will not necessarily define the requirements of the next conventional conflict.

OBJECTIVE FORCE 2020: THE RAA ROADMAP

The RAA has energetically maintained its contribution to Army’s operational commitment through the development of responsive, ‘agile and flexible’ forces.6 The past decade of operational commitment has led to the creation of an artillery regiment that specialises in rapidly employed, increasingly precise fires capable of meeting the target discrimination thresholds of joint fires planners and manoeuvre arms commanders. These fires and effects are tactically mobile, increasingly all-weather and long range, and incorporate more air-delivered munitions and attack profiles than have previously been available.

Despite the value of the experiences gained from counter-insurgency operations in Afghanistan, the RAA now needs to refocus its training towards the conventional end of the warfighting spectrum. The next war may require the bludgeoning might of massed joint fires, the layered and integrated air and missile defences, highly mobile and responsive counter-fires missions, precision fires, airspace planning and deconfliction, and persistent surveillance. The next war may also occur in the Asia-Pacific region, be fought in the littoral environment and start sooner than expected. The experiences of Afghanistan have proven of immense value to the RAA but have not fully equipped it for the next war and each of the three RAA streams will need to continue its focus on future conflicts in the current operating environment.

JFE

Just as the Federal Government is incorporating a larger United States (US) military presence into Australia, the RAA will continue to emphasise the importance of joint aspects of fire support and the importance of international accreditation through close ties with the US joint fires community. Currently the RAA’s centre of excellence, the School of Artillery, is conducting the Joint Fires Observer program, accredited by the US Joint Staff and Joint Fire Support Executive Steering Committee and ratified by the Joint Fires Observer Memorandum of Agreement.7 There is also an increased RAA assimilation in the ADF Joint Terminal Attack Controllers program at both the instructor and trainee level, which has resulted in an increase in the RAA’s ability to operate a common air-ground picture in support of manoeuvre operations.

The RAA is also increasingly ready to support amphibious operations. The RAA’s acquisition of the M777A2 155mm ultra-lightweight howitzer, combined with the modularity of gun batteries, has increased the gun line’s readiness to support the embarked force, as has the increased training of JFTs in naval gunfire support missions under the Joint Fires Observer program.8 These new lightweight howitzers, in addition to the enhanced JFTs incorporating joint terminal attack controller and joint forward observer capabilities, the highly capable tactical unmanned aerial system and the persistent surveillance suites, are high profile instruments contrib- uting to the Army’s ability to escalate or de-escalate the projection of force.

Further contributing to the Army’s flexibility in the spectrum of conflict is the RAA’s implementation of precision fires imagery generators and viewers at combat team level, and digital terminal control systems at platoon level. In addition, officers and soldiers alike are being offered increased training in collateral damage estimate methodology on RAA courses. Despite these advances to enable additional agility within the JFE force across all ends of the spectrum of conflict, it is foundation warfighting which must be emphasised as the ‘core competency that the Government demands of Army’.9

GBAD, sense, warn and locate, and air-land integration

The Air Land Regiment has shifted its focus from defeating enemy air assets to protecting the multi-role combat brigade and integrating the air-land battle. This subtle shift in focus is responsible for a radical shift in regimental culture and tactics. Foremost, this means possessing GBAD and locating capabilities that are protected, mobile and digitised, moving with and supporting the multi-role combat brigade in a conventional fight. It also means possessing highly trained and integrated personnel with enabling technologies sited across the theatre air control system to ensure that operations are effectively planned and communicated across the joint and combined space. Finally, it means ensuring that all components of the regiment are capable of communicating and synchronising.

Provided that government funding for Land Project 19 Phase 7B continues, the 16 Air Land Regiment force protection capabilities will be revolutionised.10 This remains critical for ensuring that future deployed forces receive appropriate levels of force protection from surface-to-surface fires and air threats. With the rapid acquisition of the Giraffe Agile Multi-Beam Radar, the Air Land Regiment now has the foundations for an extraordinary future capability. The RBS-70, despite being a capable short-range air defence system against helicopters and unmanned aerial vehicles, will be augmented or replaced with more capable systems that can fully protect the deployed force against the full set of likely air threats. Until its replace- ment, the focus for the RBS-70 will be mobile operations, operated from protected mobility air defence variants, fighting and communicating with the lead battlegroups of the multi-role combat brigade, to defeat rotary wing and unmanned aerial vehicle threats. The future force protection capability will need to move, fight and communicate in support of multi-role combat brigade opera- tions, countering all likely threats.

As the counter-rocket artillery, mortar capability exits Afghanistan, 16 Air Land Regiment will refocus from counter-rocket artillery, mortar towards a conventional locating capability, enabling counter-fires solutions in support of the multi-role combat brigade. The Giraffe Agile Multi-Beam Radar and lightweight counter mortar radars will remain central to this capability; however, the key shift will be in the transition from static sensor operations that provide warning only, towards mobile sensor operations which trigger fire missions in direct support of the multi-role combat brigades. Re-learning the art of locating will be a challenge to the unit — this will be a necessary skill for the next war.

In parallel to the development of the joint terminal attack controller capability, 16 Air Land Regiment has developed capability bricks which will improve the Army air-ground system component of the theatre air control system. These force elements are being equipped and trained to enable effective joint and combined integration for air-land operations. Such force elements include brigade and divisional level staff, trained and equipped, to enable air planning and resourcing in support of manoeuvre operations, at a level not previously realised in the Australian Army.

With three distinct capabilities within the one regiment, training officers and soldiers across all these disciplines will be a considerable challenge. To create deployable capability bricks which can provide locating, integration and protection capabilities, the Air Land Regiment will retain a high-tempo training regime that attempts to parallel the force generation cycle of Plan Beersheba.

STA

The counter-insurgency environment has offered an invaluable proving ground for the Army unmanned aerial system capability and has demonstrated the capacity of its RAA operators to adapt and thrive in an unfamiliar role. Not unlike the Air Land Regiment, 20 STA Regiment will undoubtedly continue to feel the training stresses of force generation in the lead-up to Objective Force 2020. While the extent of the unmanned aerial system capability will continue to be explored and realised post-Afghanistan, an evolutionary shift away from reactionary support to manoeuvre forces must occur within the wider Army. Led by the procurement of the Shadow 200 system, Army’s unmanned aerial system acquisition strategy to 2020 emphasises a shift in capability focus towards support for pre-planned intelligence-led operations and artillery targeting.

Fundamentally, the reliance on the provision of platforms must be replaced by the quality, accuracy, currency and relevance of the information they provide. This transition in operating mentalities represents a vital paradigm shift in the approach to contemporary warfighting. Through more scrupulous direction, provision, integra- tion and management of ISTAR sensors and collection assets, operational manoeuvre scope can be drastically reduced to mission critical tasks only. Using the Afghanistan battlespace as a medium for translation, greater ISTAR provision in support of opera- tions traditionally conducted by manoeuvre agencies can reduce the requirement for ground movement. This, in turn, immediately enhances land force protection by reducing operational risk and offers the tactical commander vastly superior combat information from which more specific and critical task-focused operations can be planned.

The RAA of 2020 is a highly flexible, adaptable and specialised organisation of superior technical and tactical competence in land and joint operations. Through the mutually supportive functions of JFE, air-land integration, GBAD, battlespace manage- ment, sensor coordination, ISTAR, artillery intelligence and support to joint targeting, RAA 2020 will represent a critical force capability in the modern battlespace. The provision of such a capability requires the acquisition, management and employment of appropriate artillery major systems, realistic and pervasive collective training of all the artillery streams, and inherent organisational flexibility within the RAA itself.

Risks to the evolution of the RAA

Despite the overwhelming ambition of the RAA to maximise its joint capabilities in support of future land operations, a number of inherent risks exist that may destroy this momentum. First, the RAA will be competing for a fair share of the 23% of the Defence budget apportioned to Army; under Project Land 17, in order to meet the Chief of Army’s vision of ‘highly protected … combined arms teams’, the RAA had previously received approval for the acquisition of a fully armoured self-propelled howitzer system.11 This capability was set to provide highly protected firepower and tactical mobility commensurate with the manoeuvre requirements of the combat teams and battlegroups they support under Plan Beersheba. The federal budget of 2012 saw a move away from this capability and towards a more agile field artillery capability with the acquisition of a further eighteen M777A2 howitzers.

While additional M777A2s will enable the application of digitally executed precision engagements, they are not the final word in providing agile offensive support to the army of 2020. The recent decision to retire the RAA’s 105mm L119 Hamel gun has streamlined ammunition and fleet management, but is a risk to the potential agility of an embarked force as it executes ship-to-objective manoeuvre. L119s are not only capable of engaging with a smaller burst radius than the M777A2, but are also approxi- mately half the weight.12 L119s can be underslung by S-70 and MRH-90 rotary platforms, while simultaneously underslung with ammunition crates by a CH-47. The M777A2, though clearly a market-leading ultra-lightweight 155mm howitzer, may only be underslung by a CH-47.

In the amphibious environment, a central focus of the 2020 Objective Force deployment capability, the replacement of the L119 force not only increases the cubic meterage required for storage of the embarked JFE capability, but also limits the flexibility of deployment by air in support of the transition to land operations. Reinstating the L119 Hamel gun fleet and using the advanced field artillery tactical data system to replicate the existing digital rela- tionship between JFTs and the gun line could easily mitigate these risks and would afford greater flexibility in amphibious employment.

Though the increased acquisition of the M777A2 is far from disappointing, it must be noted that the requirement for the self-propelled howitzer remains extant as long as the ADF retains a mechanised force capability. Media focus on the cost of Land 17 has rarely offered an explanation of the capability, or a comparison with the relative expense of other projects. It is therefore prudent to remember that “History has clearly demonstrated that ‘peace dividends’ invariably become ‘peace liabilities’ when the military must restore its capabilities when the next threat arrives.”13

Another area of risk is the increasing gulf between the Regular Army and the Army Reserve. As highlighted under Plan Beersheba, Regular and Reserve forces must be fully complementary if they are to successfully implement government policy. Currently, RAA Reserve units are maintaining an offensive support capa- bility through adopting mortar equipment, orders of battle, command and control structure, and tactics, techniques and procedures. These training models are not complementary to the integration of Reserve artillery forces into Regular orders of battle. This disparity can be mitigated through equipping the Reserve artillery with digital fire control systems, establishing a command and control structure to enable a Reserve JFECC to be fully interoperable with a Regular JFECC and increasing simulation training for Reserve JFTs.

It is also vital that the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) and the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) meet the RAA’s march towards increased joint operations with the same vim and vigour. The RAA has already crossed the Rubicon by restructuring the former 16th Air Defence Regiment to become 16 Air Land Regiment as a unique capability to support the Army’s link to air operations. The creation of 16 Air Land Regiment is the first step towards a joint air land unit which will better equip the ADF to meet air-land integration requirements in joint operations. It is critical for the viability of Army’s air-land operations that 16 Air Land Regiment’s capability is understood and reciprocated by air opera- tions elements of the RAN and RAAF.

Finally, there is a risk to the future of the RAA after Afghanistan if the wrong people are recruited, screened and employed. The Regiment maintains a strong combat culture which has, at its heart, an intrinsically analytical quality. Under the remodelled trade structures the RAA has identified that those qualities that define an excellent gun number do not necessarily define an excellent radar operator. The contrasts between trades are innumerable but appreciable, and each demands unique physical and intellectual qualities. The RAA must be supported in its determination to select and train candidates considered most suitable for employment within each of its trade models — this begins at the recruiting level through aptitude testing, is continued through initial employment training for allocation to trade, and further into monitoring and suitability screening for specialist capability training. The RAA is strongly positioned to harness the full scope of recruiting successes, including the employment of women, across its new trade models. This strong position will be jeopardised if the RAA is constrained in its ability to select appropriate candidates for its wide variety of positions.

CONCLUSION

After decades of doubts over its future and challenges retaining its unique heritage and identity, the participation of the RAA in Afghanistan provided an opportunity to display and refine the artillery capability. The Afghanistan experiences have enabled the RAA to evolve, refining, enhancing and reinforcing its crucial role in the process. With the imminent conclusion to the Australian commitment in that theatre, the RAA will reconstitute and reorientate towards providing an invaluable capability for Army in future conflicts; this capability, however, may be entirely different to that required during its most recent deployments.

The artillery capability of 2020 will be unique, merging the mutually supportive functions of JFE, air-land integration, GBAD, battlespace management, sensor fusion, ISTAR collection, processing and dissemination, artillery intelligence and support to joint targeting. Achieving the artillery capability of 2020 will require appropriate artillery major systems, realistic and pervasive collective training of all the artillery streams, and the inherent flexibility of gunners as an organisation. There will be significant risks and challenges in achieving the artillery capability of 2020, but it must remain the focus of every gunner to meet those challenges and increase the capability of the Royal Regiment for years to come.

Endnotes

1 LWP-CA (OS) 5-3-2, Target Engagement, Coordination and Prediction – Duties In Action, Vol One, 2010, Chap 4, Para 4.2

2 HMSP-A Directive 29-09, Army Force Modernisation Plan for the Royal Australian Artillery (Field Artillery) Capability.

3 Minutes of the FORCOMD JTAC Synchronisation Conference – 28 February 2012.

4 P. Leahy, ‘The Army in the air, developing land-air operations for a seamless force’, Australian Army Journal, Vol. II, No. 2, Autumn 2005, Land Warfare Studies Centre, Canberra.

5 LTCOL N.J. Loynes, CO’s message, accessed on : http://intranet.defence.gov.au/ armyweb/Sites/20STAR/comweb.asp?page=48710&Title=Welcome (2012)

6 LTGEN D.L Morrison, AO, speech to the Sydney Institute, February 2012, accessed via www.army.gov.au

7 JCAS AP MOA 2010-01, Joint Fires Observer, 20 March 2012.

8 Morrison, address to Royal Australian Navy Maritime Conference, January 2011, accessed via www.army.gov.au

9 Morrison, speech to the Sydney Institute.

10 SGT A. Hetherington, ‘Battlefield Tested’, Army News, 17 February 2011.

11 Ibid.

12 M119/L119/L118 Performance Specifications (2000), accessed via Federation of American Scientist Military Analysis Network at http://www.fas.org/man/dod-101/ sys/land/m119.htm

13 Ibid.