On 11 September 2001, the United States homeland was subjected to a complex, coordinated and devastating terrorist attack. In less than two hours, New York’s World Trade Center and a portion of the Pentagon had been destroyed, and four commercial airliners had been lost with all passengers and crew. The death toll from these attacks was over three thousand, causing the United States to respond to the tragedy by declaring a ‘war on terrorism’. President George W. Bush stated that the elimination of terrorist groups with a global reach was to become a national strategic objective.

An anti-terrorist coalition has since destroyed the al-Qa’ida organisation in Afghanistan and has overthrown the Taliban regime. Yet, despite these achievements, the fight against terrorism will be long, costly and difficult. While military action is important, so too is the civil effort. To this end, the Bush Administration has created a new cabinet-level portfolio for Homeland Security while additional resources have been committed to improving the preventive security and intelligence capabilities for counter-terrorism. Outside the United States, other countries such as Australia and Britain are also reassessing their arrangements for countering terrorism. 1

The American response to the attacks of 11 September 2001 suggests that President Bush’s aim of protecting the United States and its allies from the threat of terrorism will require a comprehensive approach. A set of countermeasures is needed that can address every aspect of terrorism before, during and after an attack. The aim of this article is to propose a framework for dealing with a generic terrorist threat—a framework that can be used to evaluate the completeness of any strategy for combating terrorism. The proposed framework divides terrorists’ offensive efforts into three phases of preparation, crisis and consequence. It is argued that each of these phases involves a particular set of terrorist activities that, in turn, demand the application of specific countermeasures.

Over the past thirty years, the world has witnessed a significant shift in the techniques used by international terrorist groups—from limited hostage-siege situations to mass-casualty attacks. In the 1970s and 1980s, terrorist techniques tended to impose limits on the physical damage or casualties that could be inflicted in any particular attack. 2 The historic use of bombings, a terrorist technique of choice, was often constrained largely because there were obvious limits to the size of the explosive devices that terrorist groups could assemble and transport. Similarly, attacks using small arms, including the use of submachine-guns, were nearly always limited in terms of casualties. The aim was to publicise a cause, rather than to kill large numbers of individuals.3

Over time, most Western nations responded to the hijacking threat by developing sophisticated specialist capabilities aimed at resolving hostage-siege crises by force and by using improved security methods at airports, such as metal detectors to scan luggage. By the late 1980s, these efforts largely blunted the hostage threat posed by terrorists.4 Starting in the early 1980s and evolving rapidly during the 1990s, however, a disturbing new trend of religious terrorism began to emerge with an apocalyptic element that was used to justify inflicting mass casualties. 5 Events such as the 1983 Islamic terrorist suicide truck-bomb attack on a US Marine facility in Lebanon that killed over 200 Marines foreshadowed the mass-casualty terrorism of the future. Another disturbing aspect of the changing character of terrorism was the use of unconventional weapons to try to inflict mass deaths. The Japanese Aum Shinrikyo (Aleph) sect’s 1995 attack on the Tokyo subway system used sarin gas and highlighted fears that terrorists would employ chemical and biological weapons in the future.

As with the hostage-siege phenomenon of the 1970s and 1980s, many Western countries have responded to the threat of mass-casualty terrorism by trying to develop dedicated counter-capabilities. These capabilities include measures aimed at the crisis and the consequence management phases of a situation in which a weapon of mass destruction (WMD) or high-yield conventional explosive may be involved.6 The term consequence management refers to the use of measures to mitigate the effects of terrorist attacks, particularly attacks that might involve chemical, biological, radiological or nuclear weapons, or high-yield conventional explosives (CBRNE).7

The events of 11 September suggest that the crisis phase of a terrorist attack is too fleeting to rely on immediate crisis management capabilities alone. The 11 September 2001 crisis phase of the al-Qa’ida attacks on the United States was over in two hours and climaxed in the missile-style attacks using hijacked aircraft against the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. During the attacks, US crisis-management options were limited to shooting down the hijacked airliners and accepting the loss of the innocent passengers aboard.

The trend towards increasingly lethal terrorist tactics that culminated in the 11 September attacks has significant implications for how Western nations address the threat of terrorism. There are two areas of special concern. First, there is the possibility that the scale of the destruction achieved in the al-Qa’ida attacks of 2001 has ‘re-calibrated’ the scope of terrorist actions, opening the possibility that all follow-on attacks will aim for similar casualty levels. Second, there is the likelihood that the al-Qa’ida terrorist organisation and others like it are capable of foreseeing, and planning to survive, a determined Western response on their infrastructure. It is possible that a second strike may be planned and be executed at an advantageous time—perhaps after an apparently conclusive Western counter-strike against al-Qa’ida and its Middle Eastern supporters.

If the world is on the brink of a new age of mass casualty or catastrophic terrorism, then experience suggests that two imperatives are necessary to combat the new threat. In the first place, priority of effort should go into pre-empting terrorist efforts before they coalesce into an active crisis. Once a crisis occurs, it may be impossible to avoid devastating consequences. Second, the modern terrorist must be viewed as an adaptive enemy that can be expected to defeat preventive measures, at least some of the time. 8 Crises involving terrorism will, therefore, continue to occur and consequences will continue to be generated. As a result, highly effective crisis and consequence management capabilities are essential for the security of modern Western democratic societies.

The above conclusions suggest that the threat of terrorism can only be effectively addressed by possession of a comprehensive array of capabilities that can be employed at any point during an attack. It is therefore useful to examine the anatomy of a generic terrorist threat in the age of mass-destruction terrorism. In analysing a generic threat, it is necessary to make a number of generalisations and assumptions. Without the latter, however, it is impossible to develop a functional model of counter-terrorism.

The 11 September attacks on the United States illustrated a trend that has been emerging in international terrorism since the 1980s: sophisticated terrorist groups are prepared to devote considerable effort to developing novel and devastating operational methods. A lengthy preparatory phase preceded several of the more devastating attacks of the past ten years.9 During this phase, capabilities were honed, operatives were recruited and trained, resources were positioned, and the mechanics of attack were researched and planned. 10

In contrast with the long preparatory phase, the terrorists’ actions coalesced into a crisis very quickly. On 11 September 2001, final ‘deployment’ for, and execution of, the attack by al-Qa’ida operatives took place within a few hours. As the events of that terrible morning demonstrate, the US Government lacked the quick-response capabilities to prevent the attack from being pressed home against any of its targets, much less save the innocent people aboard the airliners.11

Consequences began to be generated even before the last of the four aircraft had crashed. Significantly, the 11 September attacks were assaults that generated immediate and catastrophic casualties. In contrast, in a successful large-scale CBRNE attack on a Western city, the consequences are likely to be more protracted. For example, unlike the 11 September attacks, in a nuclear or chemical attack, a massive decontamination of urban areas would be required, while delayed casualties would probably emerge over a long period. In such circumstances, a consequence management phase of perhaps two or more years is a realistic and chilling scenario.

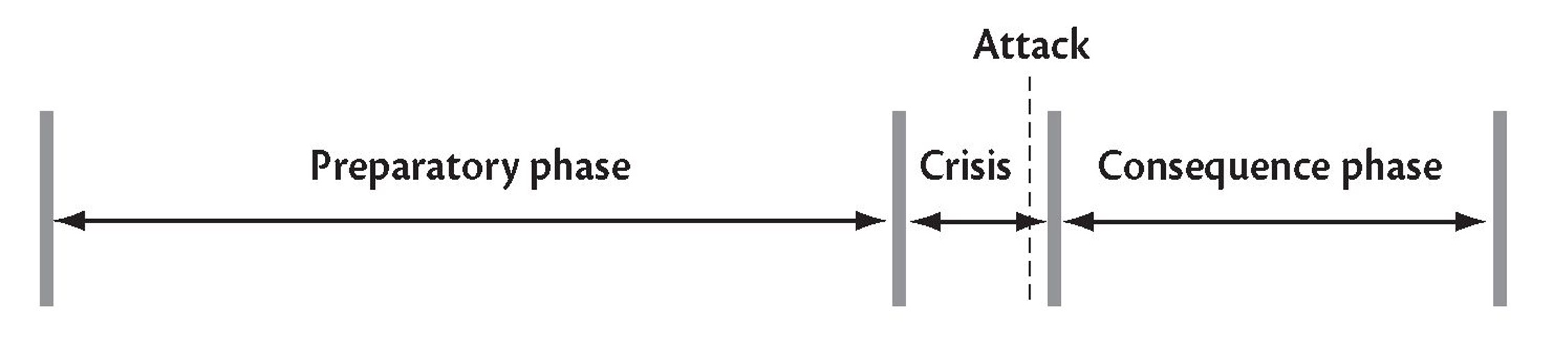

The above brief analysis suggests that a mass-casualty terrorist attack might consist of a long preparatory phase (perhaps several years), a brief crisis phase (perhaps a few hours) and a long consequence phase (again, perhaps several years). When portrayed graphically, a mass-casualty terrorist attack might appear as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. ‘Generic’ Terrorist Attack Timeline

A similar schematic timeline could be applied to a terrorist campaign, in which a number of attacks are launched using a range of tactics and weaponry. In such a case, the crisis phase could be drawn out, with attacks and their consequences overlapping.

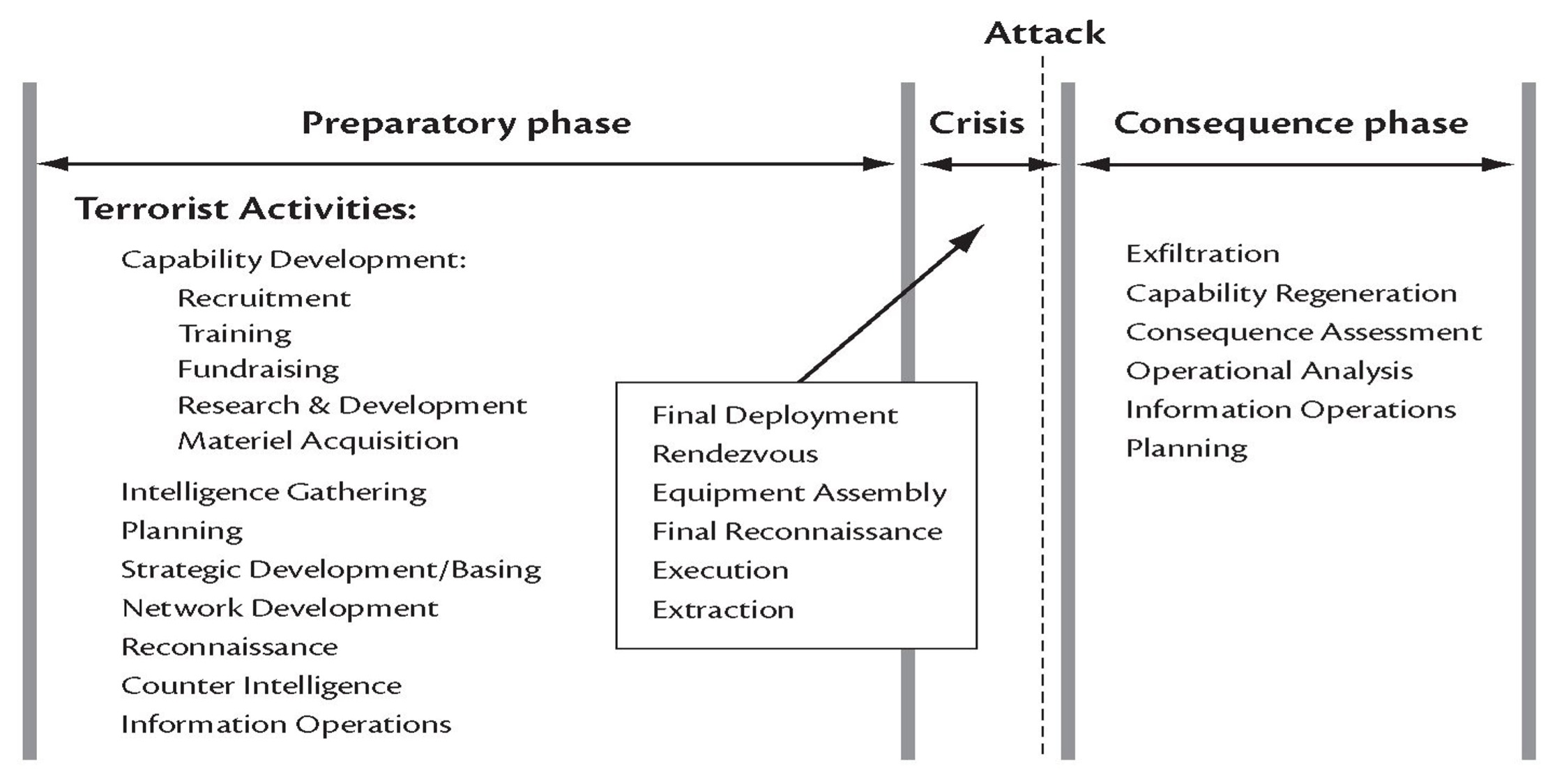

Using the generic model of preparatory, crisis and consequence phases, terrorists’ actions throughout the evolution of their plan of attack can be illustrated. Represented graphically, the attack sequence would be as illustrated in Figure 2.

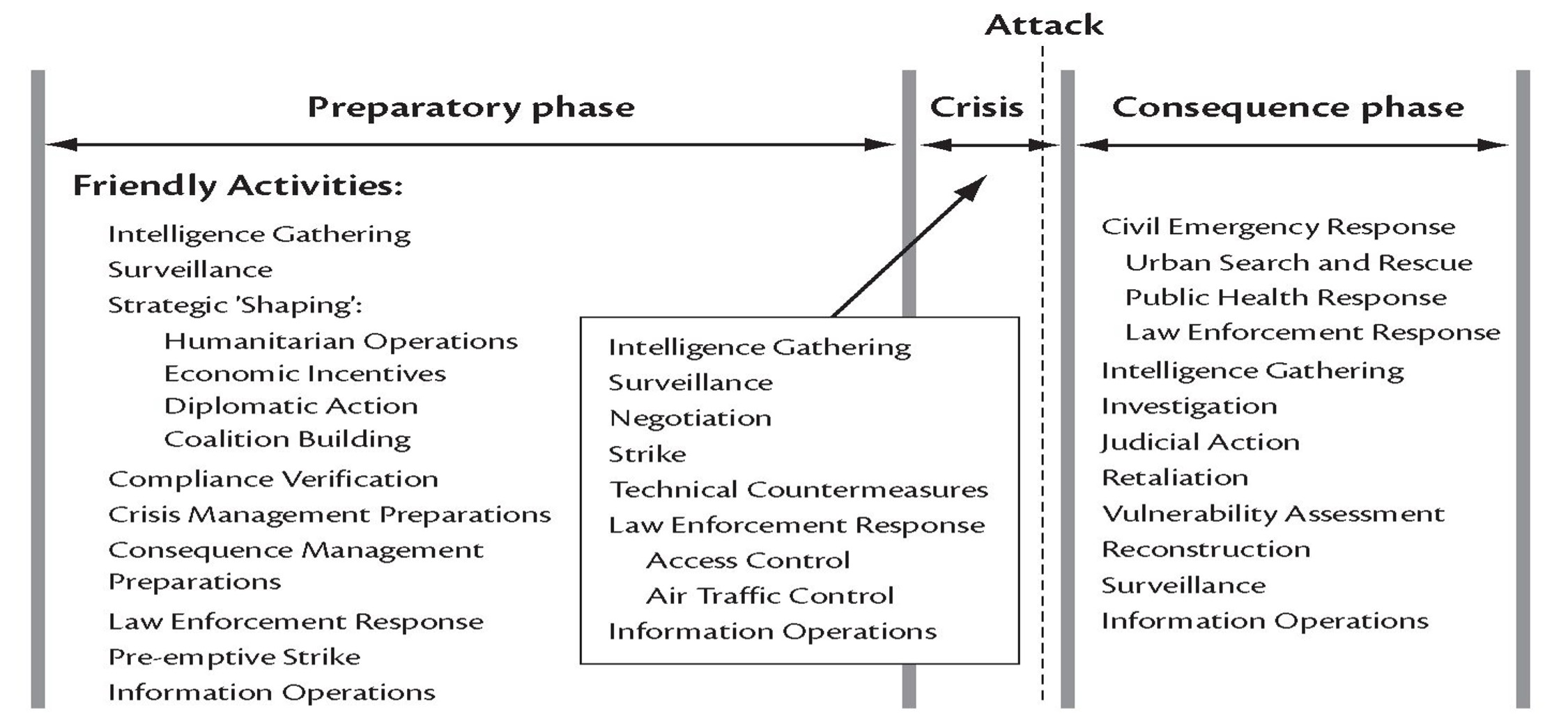

Using this model based on phases, countermeasures can be identified and arrayed against terrorist activities, and a comprehensive suite of measures and capabilities then emerges, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Using the generic model, it is possible to compare the terrorist activities under way in each phase with the corresponding government countermeasures. In this way, it is possible to determine whether any serious gaps exist in counter-terrorist strategy.

The Preparatory Phase of Counter-Terrorism

During the preparatory phase, terrorist activities tend to be low profile and often difficult to link with hostile intentions. Counter-terrorist measures during this phase need to focus on intelligence gathering and surveillance aimed at detecting radical groups and determining their motivation and intentions. Such efforts may also yield benefits by detecting terrorist-related criminal activities, such as drug trading.

Figure 2. ‘Generic’ Terrorist Activities Timeline

Intelligence gathering may be successful enough to allow pre-emptive strikes to be carried out against concentrations of terrorist activity or capabilities.12 Intelligence efforts may also point to emerging terrorist tactics, enabling new crisis and consequence management capabilities to be developed.13 Selective use of information operations to give visibility to these defensive preparations (without compromising operational security) could have both a deterrent and a denial effect.

It should be noted that the above measures are largely reactive and, with the exception of possible pre-emptive strikes, cede the initiative to the terrorist. There are, however, proactive countermeasures available to democratic governments during the preparatory phase. These countermeasures fall into two classes: the direct and the indirect. Direct countermeasures consist mainly of law enforcement and military activities, including strike operations using air power or special operations forces.

Indirect countermeasures consist of programs aimed at addressing the antipathies that motivate terrorists’ actions. Examples include humanitarian aid programs, which should be synchronised with other diplomatic and economic initiatives, to deprive the terrorists of a recruiting base of aggrieved persons. Such measures operate most successfully through diplomatic or economic channels but they are part of a broader psychological or information operations campaign.

Figure 3. ‘Generic’ Terrorist Countermeasures Indirect countermeasures seek to shape the strategic environment in which any terrorist war is fought. Such countermeasures are difficult to aim at any specific terrorist activity and must be viewed as long term in nature. Preparation is a key factor in formulating an indirect countermeasure strategy, and the generic phase model might be refined by depicting indirect countermeasures, or strategic shaping, as a permanent feature of a counter-terrorist campaign, covering all phases of action.

The Crisis Phase of Counter-Terrorism

In the crisis phase of a terrorist attack, there may be limited opportunity to apply any tactical countermeasures—particularly if suicide cadres are used. Nevertheless, comprehensive tactical crisis-management capabilities are still essential, particularly if the crisis phase rapidly merges into a consequence phase. A competent response to the crisis by government agencies, however fleeting, is important to maintain public confidence and to avoid the possibility that terrorists may gain a psychological advantage. The deployment of credible crisis-management capabilities, accompanied by aggressive and robust information operations is a vitally important measure in establishing a public perception of a competent response.

Historically, crisis management techniques have tended to emphasise the types of counter-terrorist capabilities usually associated with traditional hostage-siege situations. The new dimension of threat posed by nuclear, chemical and biological terrorism demands a range of technical response capabilities such as bomb disposal, chemical and biological agent detection and identification, vaccine storage and casualty evacuation. These highly specialised and demanding areas of expertise are beyond the competence of small jurisdictions and suggest the need for a national counter-terrorist organisation.

The Consequence Phase of Counter-Terrorism

During the consequence phase of a mass attack, terrorists’ efforts may be devoted to exfiltration of surviving operatives, and strategic and tactical re-positioning for follow-on operations. Government activities during the consequence phase need to be concentrated on relief and recovery efforts to ameliorate the effects of the attack itself on the public. In nuclear, biological or chemical attacks, the number of casualties and the extent of infrastructural damage may be reduced by the use of effective consequence management. Civilian emergency services—including fire brigades, ambulance services, and public health and law enforcement agencies—are important assets, but may require a ‘surge’ capacity to which military forces or other resources may need to contribute. Moreover, a smooth transition to large-scale consequence management operations almost certainly requires frequent rehearsal to meet emergency conditions.

While consequence management is in progress, other government efforts should be devoted to direct countermeasures. These countermeasures include investigating the attack itself, and mounting appropriate military, diplomatic, economic and judicial responses. Early intelligence efforts need to be devoted to determining whether the attack is part of a coordinated campaign, assessing whether direct countermeasures such as pre-emptive strikes or the adoption of additional protective measures are possible. A close analysis of terrorist tactics is useful to guide the development of new protective and consequence management techniques in order to reduce vulnerability in the future.

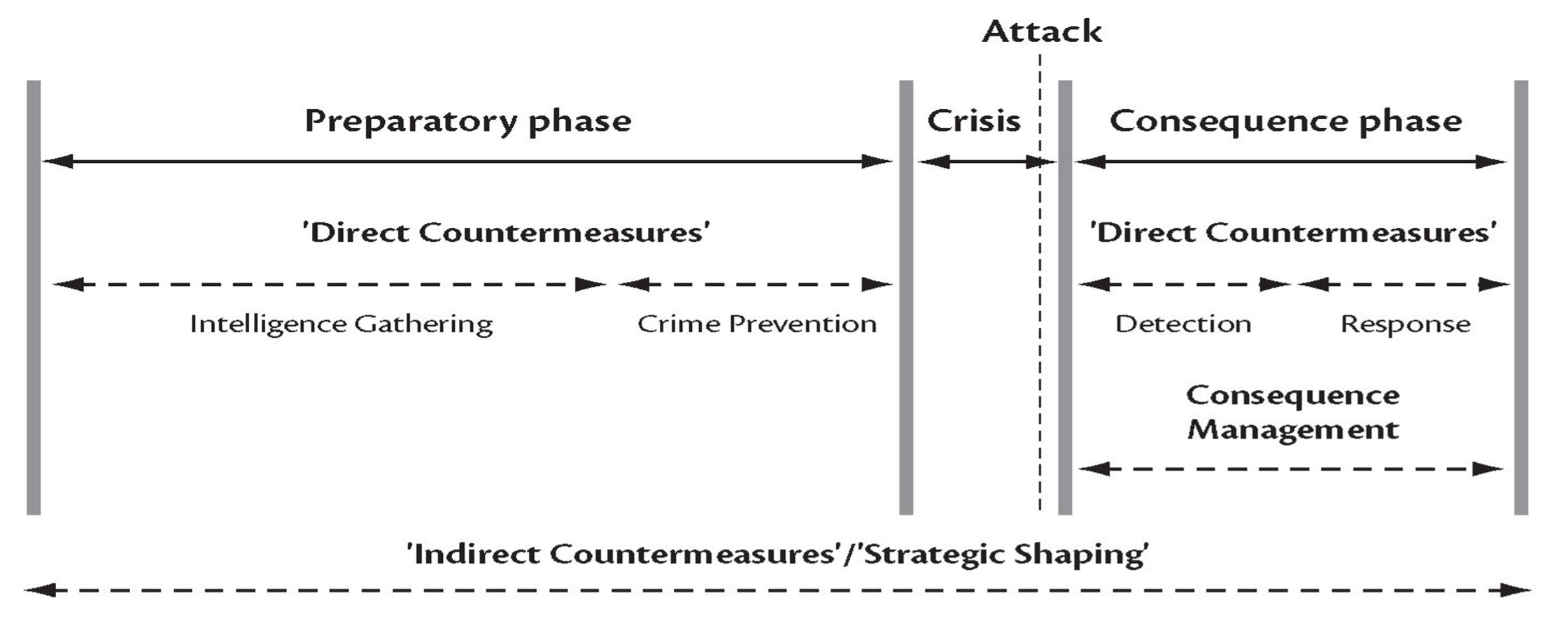

The application of direct countermeasures during the consequence phase thus suggests a further refinement to the generic phase model: the division of the consequence phase into two sub-phases: detection of the perpetrators and action against the perpetrators. This type of government activity during the consequence phase is similar to many activities during the preparatory phase. There is, in effect, a cycle of countermeasures from preparatory to consequence phases that, if incorporated, make the generic model appear as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Refined Generic Model

Planning Counter-Terrorism in a Federal System of Government

The preceding analysis shows that an extensive range of countermeasures must be available if any country is to have a comprehensive response to the threat of modern terrorism. The generic model proposed in this article has some value in identifying these capabilities in the context of a federal system of government.

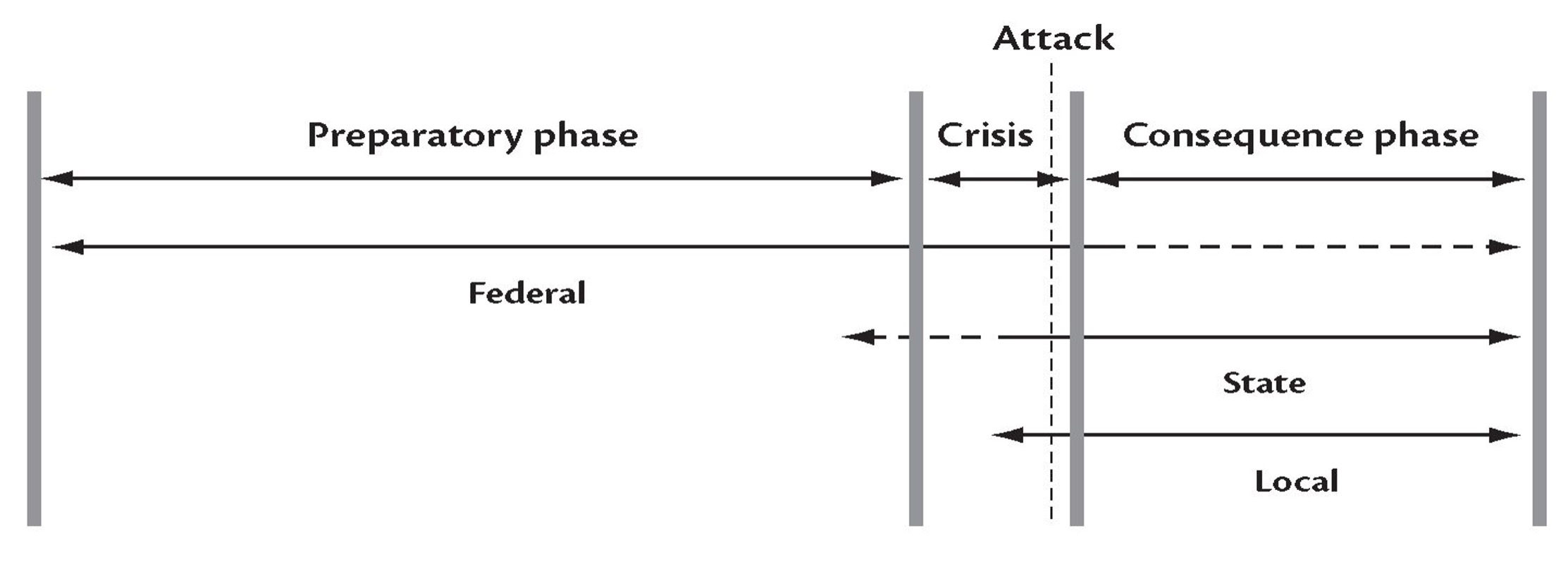

In such systems, responsibility for administration is divided between federal, state or provincial, and local or municipal levels. Federal responsibilities normally include economic, foreign and defence policies, with state and local governments being responsible for law enforcement, education and emergency services. In a federal system, however, all levels of government command resources and capabilities that are relevant to a national strategy for countering terrorism. When the sources of these capabilities are arrayed against our generic model, the result is as illustrated in Figure 5.

Federal resources can be applied across all phases—preparatory, crisis and consequence—while state and local resources become particularly relevant in the crisis and consequence phases. For at least part of the crisis and consequence phases, resources commanded by all three levels of government have an important role to play. Indeed, there may be duplication of effort and perhaps even jurisdictional conflicts that might inhibit the efficient application of resources.14 The exigencies of a ‘war on terrorism’ may eventually justify the abrogation of certain state and local government jurisdictions in favour of more efficient national management at the federal level.

Figure 5. Terrorism Countermeasures by Federal Government Source

Conclusion

The waging of a ‘war on terrorism’ poses significant challenges for liberal democratic governments. Perhaps the greatest challenge lies in the range and complexity of countermeasures that must be developed and implemented if a truly comprehensive national strategy is to be formulated. Successful execution of such a strategy requires a degree of coordination and planning. This type of planning has, heretofore, eluded most Western nations, especially those—such as Australia and the United States—which operate according to a federal governmental model. The high level of management needed for efficient and robust countermeasures in counter-terrorism may necessitate a centralised approach to planning and execution. Such a centralised, national approach may in turn necessitate the sacrifice of traditional autonomy by some intra-state jurisdictions.

This article has sought to develop a model that identifies all the elements of a terrorist threat and their corresponding countermeasures so as to gauge the comprehensiveness of any putative counter-terrorist strategy. Like the Cold War that preceded it, the ‘war on terrorism’ promises to be a long one. It is a struggle that is likely to provide ample opportunity to test the validity of this model, or any other construct that seeks to maximise the effectiveness of governments engaged in the vital task of protecting societies in liberal democracies.

Endnotes

1 For example, Australia has doubled its domestic counter-terrorist capabilities and established a Special Operations Command in December 2002.

2 For example, only 20 per cent of terrorist actions during the 1980s killed anyone. See Bruce Hoffman, Terrorist Targeting: Tactics, Trends and Potentialities, RAND, Santa Monica, CA, 1992, p. 3.

3 See Brian M. Jenkins, ‘International Terrorism: Trends and Potentialities’, in Alan D. Buckley and Daniel D. Olson (eds), International Terrorism: Current Research and Future Directions, Avery, NJ, 1980, p. 105. Bombings constituted 50 per cent of terrorist attacks between 1968 and 1992—a trend that has continued to the present day; see Hoffman, Terrorist Targeting: Tactics, Trends and Potentialities, p. 2.

4 Hoffman, Terrorist Targeting: Tactics, Trends and Potentialities, p. 13.

5 Bruce Hoffman, Responding to Terrorism Across the Technological Spectrum, Strategic

Studies Institute, US Army War College, Carlisle, PA, 1994, p. 5.

6 In the United States, ‘consequence management’ measures have been developed under the federally mandated Nunn-Lugar-Domenici Domestic Preparedness Program. See The Defense Against Weapons of Mass Destruction Act, contained in the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1997 (Title XIV of P. L. 104-201, September 23, 1996).

7 In the United States, the Nunn-Lugar-Domenici Domestic Preparedness Program is aimed at developing a national consequence-management capability against CBRNE attacks.

8 Hoffman, Responding to Terrorism Across the Technological Spectrum, pp. 14-16.

9 For example, the Aleph (formerly Aum Shinrikyo) sect’s 1995 sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway system began with research into the production of chemical and biological agents in 1992. See Global Proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction: A Case Study on the Aum Shinrikyo, Staff Statement by the Senate Government Affairs Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, 31 October 1995, at <http://www.fas.org/irp/congress/1995_rpt/aum/part04.htm>.

10 The 1998 bombings of the US embassies in East Africa provide a useful example of this type of long-term planning. See Judy Aita, ‘Bombing Trial Witness Describes Nairobi Surveillance Mission’, Middle East News Online, 23 February 2001, at <http://usinfo.state.gov/homepage.htm>.

11 Another prompt US Government response was the diversion of all inbound international flights and the grounding of all civil aviation within the continental USA. While these were sensible measures, they had a significant impact on American business and the American way of life, and thus magnified the effect of the initial terrorist strikes. An interesting sequel was the nationwide ‘grounding’ of Greyhound bus services after a (non-terrorist) attack on a driver.

12 The 1998 strikes against al-Qa’ida sites in Sudan and Afghanistan, although prompted by the bombings on the US embassies in Tanzania and Kenya, could fit into this category.

13 The CBRNE response capabilities being developed in the United States under the Nunn-Lugar-Domenici Domestic Preparedness Program are an example.

14 A lack of coordinated management may be one reason for President Bush’s establishment of a new Cabinet portfolio for Homeland Security. See testimony by Richard Davis (Director, National Security Analysis, National Security and International Affairs Division, US General Accounting Office (USGAO)) before the Subcommittee on National Security, International Affairs and Criminal Justice, Committee on Government Reform and Oversight, House of Representatives, 23 April 1998. See Combating Terrorism: Observations on Crosscutting Issues GAO/T-NSIAD-98-164, p. 3. See also testimony by Henry L. Hinton, Jr., Assistant Comptroller General, National Security and International Affairs Division, USGAO before the Subcommittee on National Security, Veterans Affairs and International Relations, Committee on Government Reform, House of Representatives; and Combating Terrorism: Observations on Federal Spending to Combat Terrorism GAO/T-NSIAD-99-107, p. 14.