The oath to serve your country did not include a contract for the normal luxuries and comforts enjoyed within our society. On the contrary it implied hardship, loyalty and devotion to duty regardless of rank.

- Brigadier George Mansford (Retd)

As Regimental Sergeant Major – Army (RSM-A), I have a unique leadership responsibility, one which I take very seriously. I am providing this article to the Australian Army Journal because I believe that there is a fundamental area of Army service that is often overlooked in discussions about culture — the role of Army’s spirit.

During my 36 years of service I have seen many changes to Army. However, I have also come to realise that there are enduring aspects of Army life — most notably Army’s spirit which forms the bedrock of how we operate and look upon ourselves. For me, Army’s spirit is a combination of our stated values — courage, initiative, respect and teamwork — along with four enduring aspects: pride, faith, mateship and opportunity. Together, these contribute to our people’s wellbeing and professional satisfaction, resulting in great benefits for Army such as higher morale and improved retention. Army’s spirit is at the heart of Army life, and while it cannot be costed, seen, heard or smelt, it is certainly valued and felt by our members. While we often talk about our former stated values — courage, initiative and teamwork — and now our most recent, respect (and I will discuss this in far more detail later), the other four elements are often taken for granted and nearly always absent from Army’s conversations about our values and culture. I believe that a discussion of these elements is worth having as, along with our stated values, these form the foundation of our human and collective spirit.

The elements — pride, faith, mateship and opportunity — are interconnected and interdependent. If Army’s leaders foster and inculcate Army’s spirit in our people, the result will be higher morale, which will both strengthen and lift our Army as a respected institution. Army members who live and represent Army’s spirit are positive role models for the small number of people who I call the ‘some of us’ who feel that these are mere words on a poster or a ‘throwaway’ line — they are not!

Army’s spirit and our nine core behaviours are a guide for all of us as to how to live our lives as Australian soldiers. I believe that the some of us misunderstand and misrepresent our spirit and values which sometimes results in oxygen for unacceptable behaviour and low personal standards. This is damaging to Army’s standing as a respected national institution and adversely affects the wellbeing of us all. The unacceptable behaviour and low personal standards of some have a negative impact on us all, as individuals and as an organisation. Our reputation is based on how we behave towards one another and towards those outside Army, whether in or out of uniform. Being a soldier is a 24/7 profession. Being a soldier is a way of life.

I believe that our officers and soldiers represent the best of Australian society. Few armies can make this claim. The human qualities that motivated us to join and to serve our nation are inherent in our stated values, but just as important are the five additional elements I have highlighted. It is the responsibility of Army’s leaders to continually draw attention to the importance of Army’s values and to foster a leadership environment in which Army’s spirit can flourish. This environment will be one in which our officers and soldiers look forward to parading each day — a very effective retention measure, and one which supports personal and professional wellbeing and satisfaction.

Pride

As RSM-A, I speak to more of our people, and to a more diverse Army audience, than the vast majority of individuals in Army. I have met very few soldiers who do not have great pride in Army — pride in the past and pride in today. The vast majority of the Australian people also share our great pride, as can be seen in the popularity of ANZAC Day. Army’s obligation is to continue to earn and retain the pride of our nation.

Every unit has much to be proud of. Our unit leaders should always ensure that their people know about their unit’s history and the achievements of their unit team, both individually and in the collective sense, in order to foster pride in the actions of those from yesterday, today and into the future. Pride in our history offers an important model to our officers and soldiers and shows them what we expect them to live up to. Leaders must always display the traits and behaviours that support pride and utilise it to fortify the unit environment. This is part of leadership by example.

Faith

Fundamental to faith is trust. In Australia, we have one of the most egalitarian societies in the world. Our officers and soldiers come from that society making our Army one of the most egalitarian in the world. Military environments are unique and demand superior/subordinate formal relationships and a willing acceptance of lawful orders and rules. These are essential to the way Army operates. Being a hierarchical organisation does not mean that two-way engagement is frowned upon or undesirable. In fact, our people deliver most and best in an environment of mutual trust. Our people feel the right to be trusted to perform their duties and meet their responsibilities. We expect our leaders to create a working environment based on trust. But trust is not automatic and freely given. Superiors are required to earn the trust of their subordinates through positive leadership, just as subordinates are required to earn the trust of superiors and colleagues through high work standards and behaviours.

It has been my experience that all trust must be validated. The willing, even cheerful, acceptance that trust must always be checked leads to effective supervision and the maintenance of standards best suited to the character of the Australian soldier. A glance at our grass roots history shows us this.

For trust to flourish in a unit, the principle and practice of tolerance of honest mistakes and learning must exist. This does not mean the tolerance of negligence which is never acceptable. Our officers and soldiers must know the difference and be held to account for negligence. When a unit has an effective and clearly understood learning mechanism, where a lesson for one becomes a lesson for all, an environment of trust is built and maintained. People can see that action emanating from lessons learned leads to superior outcomes and a feeling of confidence that the two-way trust mechanism is working and supported by all. If this approach is taken across our units then our performance will simply get better and better and our people will simply get better and better. This is faith in action.

Another important aspect of faith is care and concern for people within a unit. All officers and soldiers need their superiors to give consideration to their needs, real or perceived. This includes appropriate recognition of those who have contributed to instilling and maintaining pride.

No unit is more than the collective spirit and human talent of its people. Equipment without people is not capability, it is just equipment. No leader is more than the collective spirit and talents of his or her soldiers. In my experience leaders fail when they cannot comprehend this fact.

Mutual faith, through validated trust, lifts the spirit of our people, our leaders and our Army. Collective faith contributes to collective spirit.

Mateship

This may be a fundamentally unique term for Australians, but is not unique to militaries. In other armies ‘mates’ may be termed ‘buddies’ or ‘comrades’. In our context, mateship is not just about being personal friends or even members of the same team or unit. Mateship is about the bond that is made when we earn the right to wear Army’s uniform and the Rising Sun badge — our common thread.

I am proud to have earned the right to wear my uniform and proud to have served our nation through the Rising Sun badge for the last 35 years. I am proud to call those soldiers who have also earned the right to wear our uniform my mate whether they are my superior or subordinate, male or female.

When the some who wear our uniform let our team down by unacceptable behaviour or bad personal performance, I feel smaller regardless of my own personal standards. This is because I am just a member of our Army team, equal to all, no better or less than anyone else on our team. A mate who lets the Army team down diminishes us all. This is why mateship is so important to our collective spirit. It is this shortfall by the some that is a major problem within Army. When the shortfall is ignored this becomes a fault of our organisational culture.

Mateship can sometimes be misunderstood and give oxygen to unacceptable behaviour. It may be misunderstood because the some consider a mate as just a personal friend or immediate colleague. The some have lost sight, if they had sight in the first place. A mate includes everyone who has earned the right to proudly wear the Rising Sun badge. The attitude of a few to ‘never dob in a mate at any cost’ betrays the collective mateship and spirit our Army needs to support a healthy culture. Walking past or ignoring unacceptable behaviour or low personal standards is not courageous, it is cowardice. I can provide many examples of positive mateship. Today we have an increased focus on psychological wounds and injuries, and for good reason. Often a mate is the first responder, able to lend a heartfelt hand and give support immediately and then to follow through by being there and available. This is real mateship and is just one example of mateship in action.

Never misunderstand what mateship really means.

Opportunity

Opportunity is one of the most practical elements of Army’s spirit and is readily available. I believe that I am a much better person and a soldier because I have been the recipient of significant opportunity over my long Army career. I am fortunate to be present when the Chief of Army presents Federation Stars to officers and soldiers who have completed 40 years of service. These impressive officers and soldiers serve as examples of access to opportunity which has contributed to their longevity in Army. As their records of service are read to the audience it is clear that most have served in multiple trades and corps and accessed commissioning or other opportunities.

Yet too many leaders focus on the short-term and short-sighted needs of their units and teams. Too many decision-makers and those who make recommendations focus on policy without due consideration of the human dimension of the soldiers’ aspirations. This is detrimental to the longer term interests and health of Army. People feel let down when they believe they haven’t been heard or their needs have been ignored. The two-way trust is broken. Allowing officers and soldiers reasonable and considered access to achieve their aspirations directly contributes to a better sense of wellbeing and to Army’s spirit.

To quote a peer of mine, ‘trust is a function of character and competence’.

Respect

Respect is our newest stated value — such is the primacy of respect to a healthy culture.

When I first mentioned the unspoken elements of Army service, I did not include respect because I considered it to be part and parcel of our values. Then one day I was talking to one of my senior RSM peers about an allegation of unacceptable behaviour. My peer remarked that soldiers could not possibly treat one another in the manner detailed in the allegation if they respected one another. He was very right. I then decided that respect deserved its own consideration.

In Army, respect has three dimensions: respect for our uniform (and through this our Army), respect for one another and respect for ourselves.

Sub-standard dress, bearing and attitude in uniform or when identified as a member of Army is not acceptable and shows disrespect for oneself and for Army. Instances have occurred in the past which highlight this issue. Duty travel on public transport and behaviour at airports are one example of areas of constant concern. The sight of a badly dressed and noisy, disrespectful individual or group easily identified as members of Army by their hat or military baggage, brings us down. For the great Australian public, open displays of bad behaviour give rise to questioning whether we are worthy to represent the proud legacy of our forebears or whether Army is a suitable place to send their sons and daughters to serve. Conversely, a positive public image can reap great dividends. In my reserve unit, 8/7 RVR in country Victoria, we had a policy of our cadre staff always wearing uniform in public. Their disciplined and respectful behaviour, matched with military bearing, paid off in increased recruiting and enhanced local reputation. In the many years I have been an RSM, the vast majority of complaints I have dealt with from the public concerning bad and undisciplined behaviour have not been about the individual in the wrong, but a genuine concern for the reputation of the Australian Army. This speaks to the pride of the greater public in us as an institution. We cannot afford to diminish this pride in Army or in ourselves.

Our people must respect one another. Regardless of gender, religion and belief, sexual orientation, race or ethnicity, we are all mates. We have all earned the right to wear the Rising Sun badge. Mates respect one another. As my peer said, many incidents of unacceptable behaviour would not occur if we respected one another and our soldiers and officers understood what respect requires and what it means.

Our people must respect themselves. There is a reasonable view that Army works hard and plays hard. Playing hard does not mean drinking yourself into oblivion, using drugs, losing control, breaking the law or diminishing Army’s hard-won reputation and status. This negative type of behaviour shows lack of discipline and gross disrespect for Army and for oneself. It is a clear and present weakness and a sign of immaturity. Playing hard is robust and fair participation in sport, being law abiding and moral, responsible social enjoyment and being a mature and respectful member of our society. It is about being trusted and respected in and out of uniform, on and off duty.

Self-respect also means keeping yourself fit for battle and meeting the appearance expectations of Army and the public. I wholeheartedly support the implementation of the Physical Employment Standards which will drive a tougher, fitter, leaner and better Army. There are too many overweight and unfit officers and soldiers whose condition is within their control — and I exclude those who are recovering from wounds or injury. While I fully accept that some are suffering or recovering from injury and illness, eating a nutritious diet and exercising within restrictions may help counterbalance forced inactivity. Unless an officer or soldier has a permanent restriction that prevents fitness for battle and meeting the appearance expectations of Army and the public, this condition must be viewed as temporary. If our members are overweight and unfit it must be because of a genuine condition and not poor excuses associated with sheer laziness or a lack of enthusiasm. In my opinion, there is far too much of the latter. I ask you all to ask yourself an objective question — am I as fit as I can be? Do I meet the appearance expectations of Army and the public? Am I fit and tough enough to fight in the hardest game on earth — the battlespace of today and tomorrow? If the answer is no, strive to improve. You will not only foster respect, but improve your health with all of the benefits that accrue from a healthier lifestyle.

Some, particularly officers, have pointedly remarked to me that their workload prevents regular exercise and a healthy diet. I always ask them if they have raised their concerns with their chain of command.

We cannot afford an internal or public perception that we are too fat to fight. Being unfit or overweight because of issues beyond a member’s control is a health issue. We will support these officers and soldiers. But being unfit or overweight because of issues within a member’s control is a discipline matter. Leadership must be applied to fix this shortfall.

Courage, initiative, respect, teamwork

Our values of courage, initiative, respect and teamwork should be our ‘basic drill’ to living our profession as Australian soldiers. In the Army, from ‘day one’ every officer and soldier is taught, and forever remembers that, if caught by enemy fire in the absence of orders or direction, they use the drill of ‘run, down, crawl, observe, aim and fire’. They know that in the absence of orders or directions, this drill will save their lives and put them in a position where they can regain the initiative. On a day-to-day basis our people must use our stated values just as they use the basic drill under fire. The values ‘basic drill’ for every officer and soldier should be to simply ask themselves four questions before they take action — and we expect our people to take action. Am I being courageous (both physically and morally)? I would like to quote our Chief here, as he once commented that ‘no-one has ever explained to me how a coward in barracks can be a hero on operations. And bullies who humiliate their comrades are cowards — as are those who passively watch victimisation without the moral courage to stand up for their mates.’

Am I using my initiative? Am I respectful to the Rising Sun badge, to my mates and am I respecting myself? And am I acting for the Army team? If we follow this drill our actions will likely reflect what Army expects of us. This does not mean that every action will be perfect, but the intent to ‘do right’ is present and this will mean that you will be right. A well-intended, if imperfect action is far preferable to a thoughtless action or omission. We need to instil into our people this ‘basic drill’ based on our stated values of courage, initiative, respect and teamwork.

The ‘I’m an Australian Soldier’ Initiative

The Nine Core Behaviours:

Every soldier an expert in close combat

Every soldier a leader

Every soldier physically tough

Every soldier mentally prepared Every soldier uses initiative

Every soldier courageous

Every soldier works for the team

Every soldier committed to continuous learning and development

Every soldier demonstrates compassion

And now:

Every soldier respectful

I think it is timely now to discuss how the ‘I’m an Australian Soldier’ Initiative and the ten core behaviours that underpin its success relate to our culture and values. This initiative is a very effective yardstick for measuring our own performance and that of our subordinates, and informs our focus on training in the individual space.

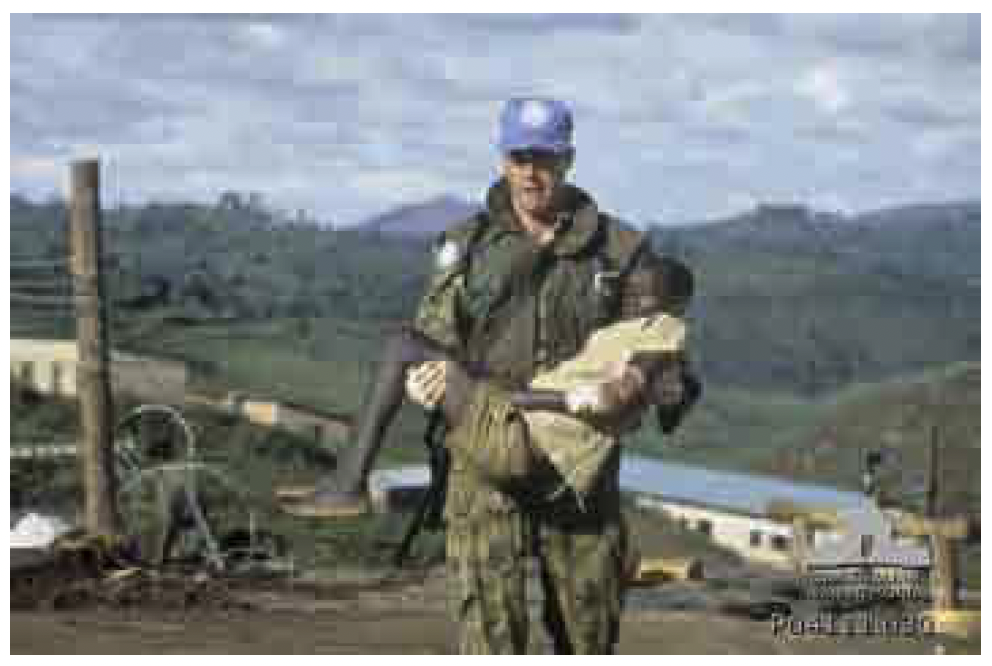

To me the greatest contemporary image of the Australian soldier is a photograph taken in Rwanda in the early 1990s. It shows an Australian soldier, Trooper Jonathan Church of the Special Air Service Regiment, cradling a sick or wounded African child in his arms. Trooper Church, later tragically killed in the Townsville Blackhawk collision, clearly a great warrior and an expert in close combat is also clearly a great humanitarian — every soldier demonstrates compassion.

Trooper Church reflects what an Australian soldier should be. I have no doubt that he was an exemplar of each and every one of the core behaviours required to meet the Initiative. I bet you he would have also been proud, he had great faith and trust, that he would have been a mate and would have known what that term really meant. He was a Special Forces soldier who had accessed his opportunity, and he embodied respect. I know that when he had to make a decision or take action he would have behaved in a courageous way, both morally and physically (and I believe you cannot be one without the other). He used his initiative, he would have been respectful to the Rising Sun badge and his Army, his mates and himself, and he worked for the Army team. We would all do well to emulate him.

Army’s spirit, which is made up of our identified and unspoken values, is strengthened by the ‘I’m an Australian Soldier’ Initiative. All three must be considered, discussed and lived together.

Many times I have used the word some to refer to those who are guilty of unacceptable behaviour or low personal and professional standards in Army. But on the whole, we have a great Army that is a trusted and respected national institution. This trust and respect has been earned though ‘hard yards’. This trust and respect was hard to win but is easy to lose. So, don’t allow yourself, or any member of your team, to become one of the some — protect and respect yourself and our Army.

Those of us who lead our teams and units must always look internally and consider whether we are fostering a team or unit environment in which Army’s spirit can flourish. This must be an environment in which the elements of pride, faith, mateship, opportunity and respect are matched by our stated values, our values ‘basic drill’, and in which we are measured in the individual sense by the ‘I’m an Australian Soldier’ Initiative.

These three, lived and considered together, will deliver Army high morale and wellbeing, professional satisfaction and a values-based culture that supports and energises us as a great national institution.

I will finish this article with a contract between each of us and our nation. Consider our contract with the quote at the start of this presentation from Brigadier Mansford. They are both compelling and both supportive of each other.

Our contract with Australia

I’m an Australian soldier who is an expert in close combat, I’m physically and mentally tough, compassionate and courageous.

I lead by example, I strive to take the initiative, I am committed to learning and to working for the team.

I believe in trust, loyalty and respect for my country, my mates and the Army.

The Rising Sun is my badge of honour. I am an Australian soldier.